-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Giuseppe Sorrenti, Ulf Zölitz, Denis Ribeaud, Manuel Eisner, The Causal Impact of Socio-Emotional Skills Training on Educational Success, The Review of Economic Studies, Volume 92, Issue 1, January 2025, Pages 506–552, https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdae018

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We study the long-term effects of a randomized intervention targeting children's socio-emotional skills. The classroom-based intervention for primary school children has positive impacts that persist for over a decade. Treated children become more likely to complete academic high school and enrol in university. Two mechanisms drive these results. Treated children show fewer attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: they are less impulsive and less disruptive. They also attain higher grades, but they do not score higher on standardized tests. The long-term effects on educational attainment thus appear to be driven by changes in socio-emotional skills rather than cognitive skills.

1. INTRODUCTION

Socio-emotional skills are predictive of major life outcomes like educational attainment, employment, earnings, health, and participation in crime (Heckman and Rubinstein, 2001; Roberts et al., 2007; Almlund et al., 2011). While the predictive power of socio-emotional skills has been established, there is an ongoing debate about how malleable these skills are. If these skills are indeed malleable, interventions targeting children's socio-emotional skills may change the trajectory of a life and lead to lasting changes in educational attainment and labour market outcomes.

In this paper, we study how a randomized intervention among eight-year-old children in Switzerland affects tracking, high school completion, and university enrolment. The promoting alternative thinking strategies (PATHS) intervention is a classroom-based socio-emotional learning (SEL) programme for elementary school students that aim to reduce behavioural problems (Greenberg et al., 1995). The intervention consists of weekly lessons and homework assignments embedded in the school curriculum. PATHS lasts for up to two years and is designed to foster self-control, patience, social problem-solving skills, self-esteem, emotional intelligence, and academic engagement.

PATHS teaches children to think twice and to look ahead. For example, in one classroom exercise, children learn to make less impulsive choices in difficult situations with the three-part “stoplight approach”. First, on the red light, children slow down, take a few deep breaths, and explain the problem they face. Next, on the yellow light, children think about solution options and the consequences of their actions, and they plan a solution to the problem. Finally, on the green light, children execute their plan and evaluate whether it worked. Teachers support children in applying the stoplight approach in role-play and real-life situations occurring in class such as a conflict with peers. Children also practice this approach in homework assignments: they describe a school-related social or academic problem, explain solution strategies to parents or classmates, and collect feedback on their solution strategies. PATHS includes elements of cognitive behavioural therapy and targets problem-solving and regulatory skills that have been associated with improved externalizing behaviour conducive to learning, achievement, and future school success (Izard et al., 2004; Fantuzzo et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2007; Raver et al., 2011; Deming, 2017).

The PATHS intervention was implemented in 2005 in Zurich, Switzerland. Its main goal was to reduce disruptive and aggressive behaviour by improving children's socio-emotional skills (Eisner et al., 2012a).1 PATHS was introduced in twenty-eight out of fifty-six randomly selected public primary schools. Randomization took place at the school level and was stratified within-school districts. The intervention was supposed to last for one school year in second grade; however, the programme was so popular that over 70% of schools accepted the offer to continue with the programme for a second year. The experimental design also included the Triple P parenting training programme, which was implemented in half of the schools in the PATHS treatment schools and in half of the control group schools. The Triple P intervention, in contrast to PATHS, was less intensive and parents received less than 2 h of intervention time on average. Triple P did not affect educational outcomes. In this paper, we focus on the PATHS intervention and, for completeness, discuss the additional intervention and evaluation results in Supplementary Appendix D.

To evaluate the long-term effects of the PATHS intervention, we follow the treatment and control groups over seventeen years using the Zurich Project on Social Development from Childhood to Adulthood (z-proso) panel. This panel surveyed children, teachers, and primary caregivers annually or biannually from late 2004 until early 2022, with the last wave interviewing children at age 24. The data include baseline and follow-up measures of children's socio-emotional skills, parenting practices, and family and household characteristics, as well as administrative and self-reported educational outcomes. The combination of multi-respondent survey data matched to administrative education records allows us to provide detailed evidence on how treatment effects evolve over time and what skills the intervention affects.

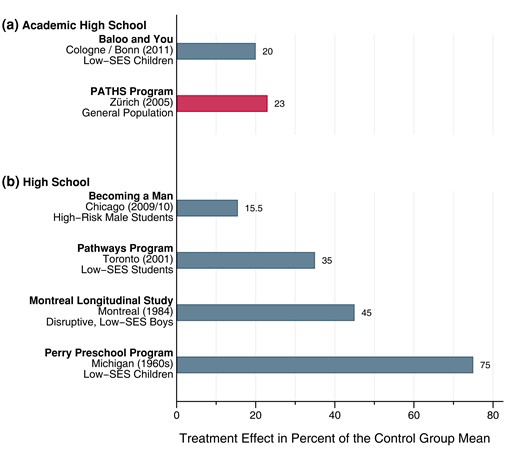

PATHS has lasting effects on educational careers. At age 13, four years after the intervention, treated children become 4.4 percentage points more likely to get tracked into academic high school (Gymnasium).2 The treatment effect persists, and treated children become 7.1 percentage points more likely to complete academic high school. This effect is economically significant. It represents a 23% increase relative to the mean of the control group. At age 24, fifteen years after the end of the intervention, the treatment group is 6.5 percentage points more likely to attend or have completed university, which is a 26% increase relative to the control group.

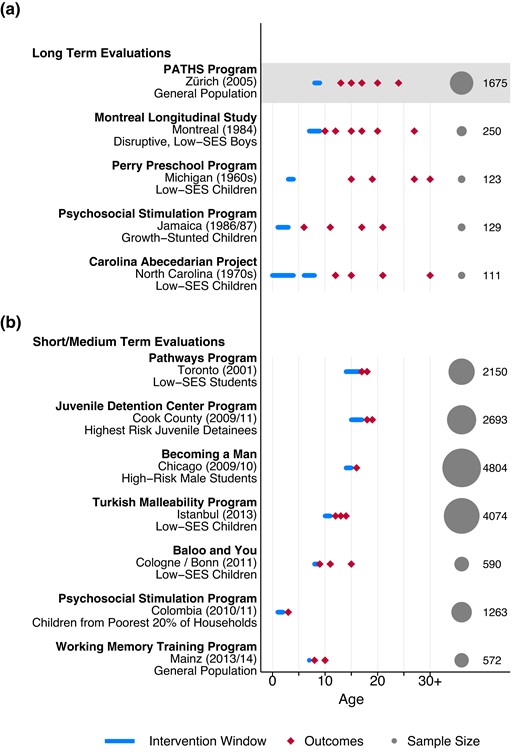

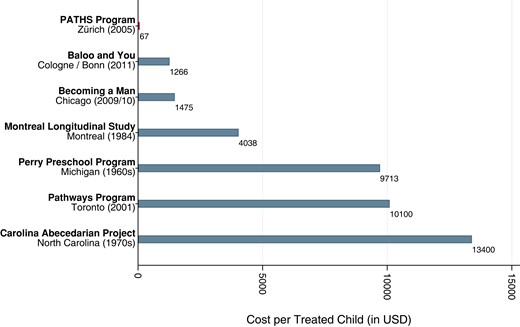

How does PATHS's effectiveness compare to other childhood intervention programmes? The size of the PATHS treatment effect is one-sixth of the treatment effect of the Abecedarian programme for college attendance (Campbell et al., 2002) and one-third of the size of the Perry Preschool Program for high school completion (Schweinhart, 1993; Heckman et al., 2010a). Our effect size on academic high school attendance is very similar to the treatment effect of the Baloo and You mentoring programme (Falk et al., 2020).

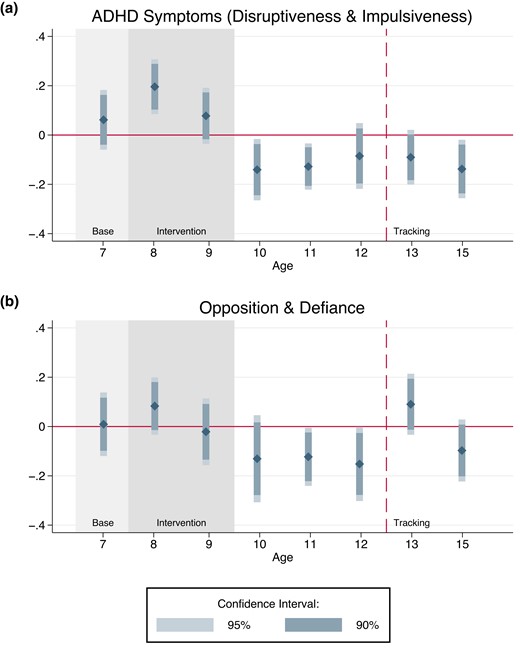

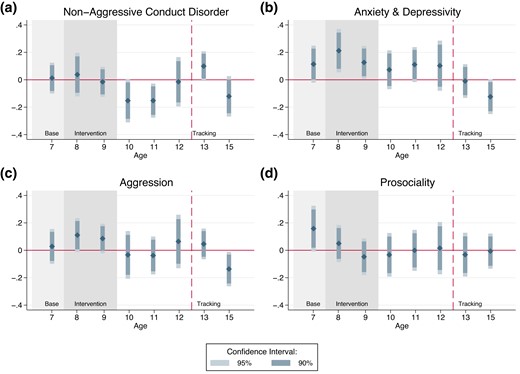

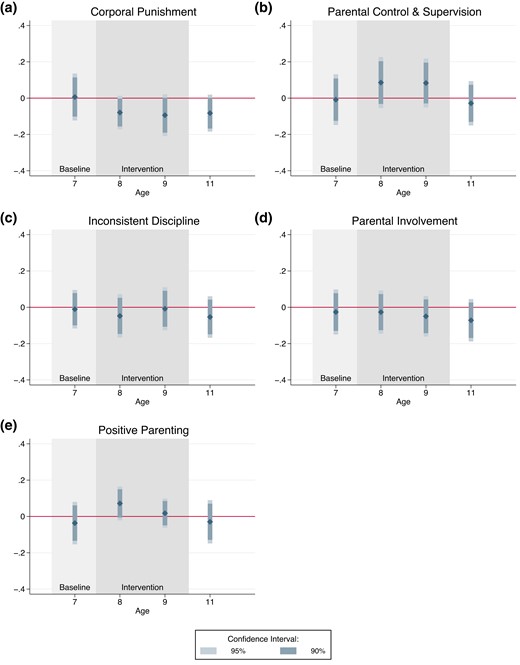

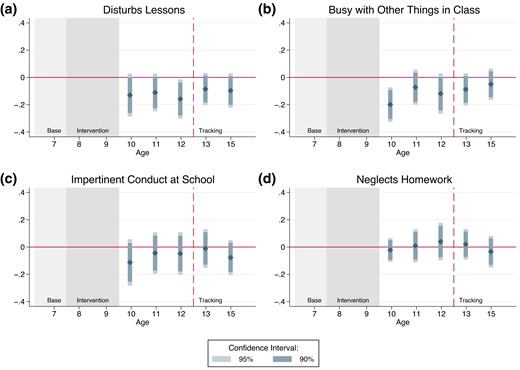

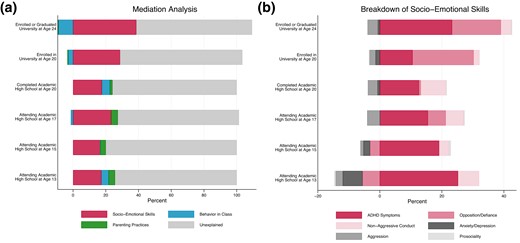

To investigate how the PATHS intervention affected children's educational attainment, we study four potential mechanisms. We evaluate changes in (1) grades and test scores, (2) socio-emotional skills, (3) children's classroom behaviour, and (4) parenting practices. We find evidence for the first three mechanisms. First, we find suggestive evidence that the intervention increases students’ teacher-assessed grades, but it has no impact on academic high school admission test scores. As grades are more influenced by socio-emotional skills and classroom behaviour than achievement tests (Borghans et al., 2016), our results suggest that the treatment effect is more likely to operate through changes in socio-emotional skills rather than through improved cognitive skills. Second, treated children display less attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms: they are less impulsive and less disruptive. Treated children also display less opposition, defiance, and non-aggressive conduct disorders (NACD). Children's anxiety, physical aggression, and prosociality are not affected by the intervention. Third, treated children are less likely to disturb lessons and more likely to focus on the teaching content in class. We do not find that treated children become more likely to complete their homework assignments, which suggests that the treatment mostly affects engagement and attention in the classroom. Fourth, we find no treatment effects on parenting practices.

Taken together, our analysis of the underlying mechanisms paints a consistent picture. The PATHS programme reduces children's impulsiveness and fosters their decision-making process. These behavioural changes improve classroom behaviour, which is rewarded by higher grades. In the long run, these improvements in grades lead students to enter the academic high school track and ultimately, university.

Our paper makes a series of novel contributions. Existing work typically studies treatment effects on socio-emotional skills or academic outcomes in isolation. Although a number of existing studies hypothesize that the long-term impact of early childhood interventions is driven by changes in socio-emotional skills, the direct empirical evidence for this link is limited. This paper fills that gap by studying both types of outcomes in a common framework and estimating to which degree changes in academic careers are mediated by changes in socio-emotional skills.

Existing childhood intervention studies either suffer from small sample sizes or are not able to follow individuals over an extended time period.3 Our study addresses both shortcomings. In contrast to some iconic childhood intervention studies, we have a substantially larger sample size and low attrition rates.4 Our ability to document how treatment effects evolve over a seventeen-year period distinguishes our work from the literature.

Our results add to recent evidence that challenge the view that effective interventions need to take place before age 6. We highlight that adding socio-emotional skills training to the primary school curriculum at ages 8–9 has meaningful long-run impacts on educational careers. Our paper thereby relates to a growing literature on other classroom-based primary school interventions targeting socio-emotional development. Alan et al. (2019) show that an intervention targeting grit increases students’ perseverance and math test scores two years after the intervention. Alan and Ertac (2018) show that an intervention targeting patience improves self-control and the ability to imagine future selves. These effects lead students to make more-patient intertemporal choices and persist over a three-year period. Schunk et al. (2022) show that training in self-regulation improves both cognitive and non-cognitive skills and makes students’ more likely to attend the academic high school track three years after the intervention. Berger et al. (2020) show that an intervention targeting students’ working memory improves both cognitive and socio-emotional skills with effects measured up to four years after the intervention. Brown et al. (2022) show that training in cognitive endurance improves student performance by 0.09 standard deviations. Cipriano et al. (2023) conduct a meta-analysis of school-based SEL programmes outside the economics literature and conclude that SEL programmes are generally effective. While Cipriano et al. (2023) find that most interventions lead to improved school climates and student behaviour, evidence on long-run effects remains extremely scarce. Hart et al. (2020) conduct a meta-analysis of education interventions targeting either cognitive or socio-emotional skills and conclude that most intervention effects appear to fade out within a few years. In contrast to existing papers on primary school interventions and the work summarized by these two meta-analyses, we have a much longer follow-up period and are the first to look at university enrolment as an outcome.

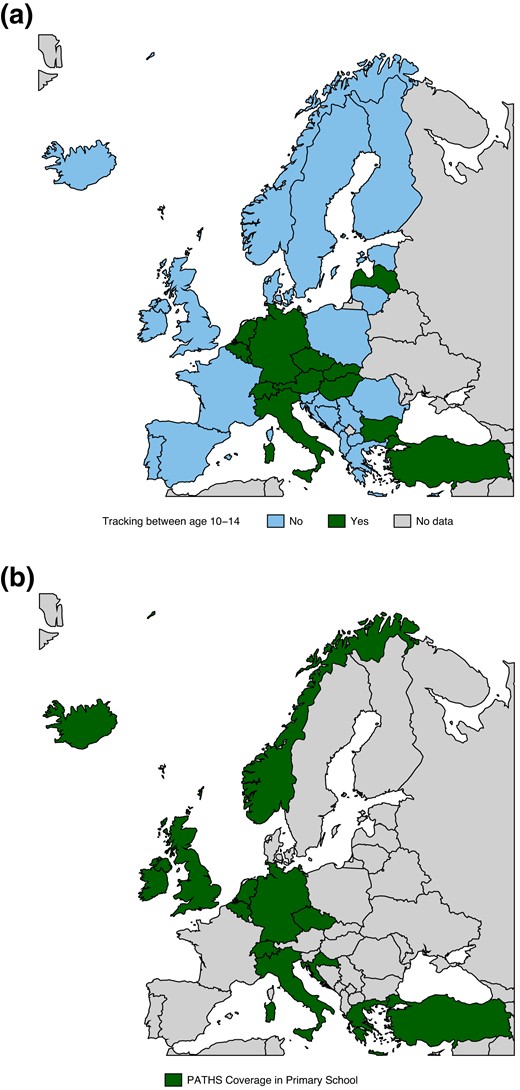

Our paper is not the first evaluation of the PATHS programme. Over the past two decades, PATHS has become increasingly popular and has been used in over thirty-six countries. Similar to the broader literature on SEL programmes, existing evaluations of PATHS focus on short- or medium-term behavioural changes in primary school (Malti et al., 2012; Crean and Johnson, 2013; Averdijk et al., 2016; Humphrey et al., 2016).5 Most of these evaluations were not designed to provide evidence of long-run effectiveness. In contrast to these studies, we follow students over a substantially longer time horizon and do not limit the analysis to survey-based behavioural measures. By looking at how the intervention affects university enrolment and graduation, we provide unique evidence on the long-term effectiveness of one increasingly popular SEL programme used in a variety of countries. In contrast to previous evaluations, our study is the first to establish a causal link between the PATHS programme, tracking, and participation in higher education.

2. THE PATHS TRAINING PROGRAMME

PATHS is a teacher-led programme for primary school children that was developed by Mark T. Greenberg and Carol A. Kusché at the University of Washington for the U.S. context (Kusché and Greenberg, 1994). The programme teaches systematic coping and decision-making strategies with the aim of fostering children's self-control, emotional understanding, and social problem-solving skills (Greenberg et al., 1995).

PATHS focuses on regulatory skills; it aims to foster social skills and improve externalizing behaviour (Greenberg et al., 1995, 1998). These behaviour changes should improve educational participation, reduce disruptive and aggressive behaviour in the classroom, and, ultimately, reduce violence, delinquency, and crime. Supplementary Table C1 provides an overview of the PATHS curriculum, which targets the following competencies:6

- (1)

Self-control and patience

- (2)

Decision-making strategies and social problem-solving

- (3)

Self-esteem

- (4)

Emotional intelligence

- (5)

Fairness and rules

(1) Self-control and patience: PATHS targets self-control and patience through several exercises. Children learn to calm down in stressful situations using breathing techniques. They learn that it is their own responsibility to avoid exploding in anger and losing self-control through the analogy of a balloon that can burst. They role-play situations in which they practice ignoring, interpreting, and handling teasing of other children. They listen to a story of a girl who learned how to control herself by calming down and recognizing her emotions. The children complete some of these exercises at home. For example, children interview their parents about situations in which they had to calm down and write a summary of how their parents managed the situation.

(2) Decision-making strategies and social problem-solving: PATHS targets decision-making strategies and social problem-solving based on the stoplight approach described in the introduction. Supplementary Figure C1 shows a poster used to explain the stoplight approach. After introducing the method in class, the teacher discusses concrete situations in which children can use the approach. Children then apply the stoplight approach in repeated role-play exercises that simulate everyday situations. These exercises involve conflict situations with peers, parents, or teachers, or problems with school assignments. In homework assignments, children describe their problem-solving approach to a specific situation. They also practice the approach at home and explain the three steps to their parents, who receive a separate information leaflet about the benefits of the stoplight approach (Supplementary Figure C5).

(3) Self-esteem: PATHS aims to increase children's self-esteem by making them aware of their strengths and skills. In one of the lessons, children learn to give and accept compliments from peers and teachers. The teacher explains the concepts of compliments and respect as well as how to express compliments. Children then practice how to give compliments to each other in the classroom. In one homework assignment, children exchange compliments with parents and other family members at home.

In another exercise, the “child of the week” receives special privileges and duties for one week. As part of this exercise, the child acts as the teacher's assistant. At the end of the week, the teacher and classmates prepare a special child-of-the-week certificate with a picture of the child and a series of compliments and anecdotes describing what attributes classmates value in the child. While this activity is supposed to foster self-esteem, it also teaches children that privilege comes with responsibilities. They are supposed to learn that being valued by others also requires contributing to the common good.

(4) Emotional intelligence: PATHS targets emotional intelligence by fostering the understanding and expression of feelings. In one lesson, the teacher reads stories and children guess what feelings the protagonist felt. In one homework assignment, children describe their feelings during a recent emotional situation and discuss with their parents how they dealt with their emotions. With this exercise, children learn about themselves and become more aware of how their behaviour affects the feelings and perceptions of peers, parents, and teachers. To facilitate the recognition and expression of feelings, children receive “feelings cards”. These cards show children expressing different emotions such as happiness, excitement, anger, surprise, sadness, and worry (see Supplementary Figure C2). Children first colour these cards and then use them to express their current emotional state by placing the corresponding card on their table. In a final step, children reflect on how to demonstrate an emotion. For example, they have to find appropriate verbal responses to feelings like anger or sadness.

(5) Fairness and rules: Starting with the first PATHS lesson, children discuss the importance of having rules and manners. They discuss with their teachers in class and parents at home which rules should be established in the classroom, at home, and in everyday life. PATHS also tries to foster children's understanding of fairness by introducing children to principles of fair behaviour. In one lesson, children have to identify fair and unfair behaviour in different situations. In another lesson, the teacher reads a story and the children discuss whether the protagonists’ behaviour is fair or unfair.

3. DATA AND INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

This section provides the institutional background of this study. First, we introduce the Zurich Project on Social Development from Childhood to Adulthood (z-proso data collection). Second, we illustrate the main characteristics of the education system in the Canton of Zurich.

3.1 The z-proso study

The data we analyse in the paper come from the z-proso panel study (Malti et al., 2011; Eisner et al., 2012b; Averdijk et al., 2016). Ribeaud et al. (2022) provide a detailed description of the Zurich Project on the Social Development from Childhood to Adulthood (z-proso). The study surveys students, teachers, and primary caregivers7 to investigate the life course of 1,675 children starting primary school in 2004 in Zurich, which is the largest city in Switzerland. Supplementary Table B1 provides an overview of the timing of the surveys, the respondents, and the response rate in nine different waves that took place between 2004 and 2022. By 2022, the study had followed children over a seventeen-year period until they were twenty-four-years old. Throughout the nine interview waves, response rates remained high. At age 24, for example, about 70% of the original sample responded to the survey.

The z-proso data include pre-intervention (baseline) and follow-up measures of children's socio-emotional skills, parenting practices, family and household characteristics, and administrative and self-reported educational outcomes. Supplementary Appendix B describes the data collection, informed consent, and ethics approval in greater detail.

Two early prevention programmes were implemented as part of the z-proso study. The first intervention was PATHS—the school-based social and emotional learning-based programme we focus on in this paper (see Section 2). The second intervention was the “Positive Parenting Program” (Triple P). Triple P encourages “positive parenting” by teaching techniques that support desired child behaviour, routines that avoid parent–child conflicts, and techniques that help the child plan (Sanders, 1999). In this paper, we focus on the PATHS intervention. For completeness, we provide more details on the Triple P intervention in Section 4 and show its treatment effects in Sections 6 and Supplementary Appendix D.

3.2 Education and tracking system

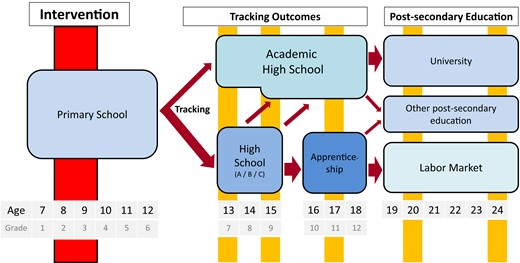

Figure 1 illustrates the school system and educational transitions in the canton of Zurich. Children start primary school at age 7. At age 12, after six years of primary school, children are tracked into different secondary schools.

School tracking and measurement of educational outcomes Notes: This figure illustrates the structure of the school system in the canton of Zurich. Children attend primary school for six years from ages 7 to 12 (Grade 1 to Grade 6). At the end of primary school, at age 12, children are tracked either into academic high school (Gymnasium) or into regular high school (Sekundarschule). The tracking outcome is determined exclusively by children's grades in the final year of primary school and academic high school admission test scores. Children can either attend an academic high school directly starting from Grade 7 (long-term Gymnasium) or from Grade 9 onward (short-term Gymnasium). The non-academic high school track comprises three lower tracks called Sek A, Sek B, and Sek C. Children attending regular high school can also transfer to academic high school after two or three years. The Matura degree, obtained upon completion of academic high school, is required to enrol in university. Students graduating from regular high school typically start an apprenticeship at age 16. Apprenticeships last two to four years. The red vertical bar indicates the intervention period. The yellow bars indicate the points in time when we observe educational outcomes.

The highest school track is academic high school (Gymnasium). Students attend this school for six years and typically graduate when they are eighteen-years old. It prepares students for university education and allows them to obtain the Matura degree required to enrol in university.8 Tracking is determined by grades and an admission test. Parents cannot choose the secondary school track and have no direct influence on the tracking outcome.

Students can obtain the Matura degree from an academic high school either through attending long-term academic high school or short-term academic high school. Tracking into long-term academic high school takes place after Grade 6. Tracking into short-term academic high school takes place after Grade 8 or 9. Later transitions are possible if a student has sufficiently high grades and passes the standardized admission test. During the first two probation years, some students initially tracked into academic high school fail to meet performance standards and move to a lower track. Additionally, a substantial number of students from the lower track move into the academic high school at different points in time. As a result, the share of students in the highest track increases by 25% during the first three years of secondary school.

4. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

4.1 Selection of schools, randomization, and definition of treatment group

Selection of participating schools: Zurich has seven school districts and a total of ninety primary schools. In each school district, eight schools were randomly selected to participate in the experiment. All fifty-six selected schools complied with the request of the City of Zurich's School and Sports Department to participate in the study.

Stratification and randomization: The fifty-six participating schools were assigned to fourteen strata cells. These cells were constructed by dividing each of the seven school districts into two groups consisting of four similar-sized schools. Within each strata, each school was randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups using a random number generated in Microsoft Excel. Schools with the largest random number in each strata were assigned to the PATHS programme (PATHS only). Schools with the second-largest number were assigned to the Triple P programme (Triple P only). Schools with the third-largest number were assigned both to the PATHS and Triple P programmes (PATHS and Triple P). Finally, schools with the lowest number received neither the PATHS nor the Triple P intervention. These schools are the pure control group.

Definition of treatment and control groups: In this paper, we focus on the PATHS intervention and define the treatment group as the group of schools assigned to one of the two PATHS treatment arms—either PATHS only or PATHS and Triple P combined. The control group consists of the pure control group and the Triple P-only group. Based on this definition, we have twenty-eight treated and twenty-eight control schools.

We include Triple P schools in the control group because this programme had no impact on children's educational careers (Supplementary Table D1). Triple P also had no impact on children's problematic behaviour or educational outcomes (Malti et al., 2011; Eisner et al., 2012b). Triple P has been shown to be effective for younger children (Doyle, 2020). In our setting, however, participation rates were low: only 27% of parents assigned to Triple P enroled in the programme and attended at least one session. Less than 19% of parents assigned to Triple P completed all four course units. Triple P parents received, on average, less than 2 h of intervention time. Eisner et al. (2011) show that parents who decided to attend courses were more likely to come from families with a high socio-economic background and be of Swiss origin.

Given that there are four treatment arms of the original experimental design, we could also estimate effects for each of the three treatment groups separately. In Section 6.3, we show that this approach leads to similar results. Alternatively, we could drop all students that received the Triple P treatment and compare only the pure PATHS with the pure control group. We provide results based on this alternative sample definition in Section 6.3. Although we lose about half of our observations with this definition, results remain very similar.

4.2 Implementation of the intervention

In the 2005/2006 school year, PATHS was implemented in twenty-eight primary schools in cooperation with the Department of School and Sports of the City of Zurich. Prior to the implementation, the original PATHS material was translated and adjusted to the Swiss context by Rahel Jünger in collaboration with the U.S. developers (Eisner et al., 2007). Rahel Jünger also implemented the programme and conducted the teacher training and supervision. This implementation was done independently from the evaluation.

In the selected schools, all Grade 2 classes were treated. Parents were not aware of the school's treatment status or the implementation of the programme in Grade 2 when enroling their children in primary schools. The level of compliance was remarkably high, with less than 6% of children changing schools between Grade 1, when baseline characteristics were collected, and Grade 2, when the PATHS programme was implemented in the treated schools. We do not find that school changes were related to the treatment status.9

To prepare schools for delivering the PATHS intervention, all teachers in charge of running PATHS lessons participated in a three-day workshop with a PATHS coach. There was usually one teacher per treated class that received the PATHS training. Teachers not delivering PATHS were not trained. During this workshop, the PATHS coach gave teachers an overview of the key concepts, classroom activities, posters, toys, and over 400 pages of materials. During the first year of the programme, teachers regularly met their PATHS coach, who gave them feedback and support. PATHS coaches also monitored the implementation and observed six PATHS lessons for each participating class. After each of these observations, the coach provided suggestions for improvements and graded the quality of the implementation.

The 45-min PATHS lessons typically took place twice per week. Treated children received PATHS lessons throughout the entire year of Grade 2. PATHS lessons replaced the class “Humans and Environment” (Mensch und Umwelt), which teaches children about the environment and organization of Swiss society. To reinforce the practice of PATHS methods, teachers also applied PATHS strategies in lessons not explicitly dedicated to the PATHS curriculum itself. Over the course of Grade 2, children received about 45 h of PATHS lessons and about 20 h of PATHS homework assignments (Eisner et al., 2007). Because the majority of teachers, parents, and children highly appreciated PATHS, over 70% of schools continued using the programme for a second year in Grade 3. The programme ended for all children at the end of Grade 3 when classes were reshuffled, and students received a new teacher.

4.3 Outcome variables and descriptive statistics

Outcome variables: We evaluate the long-term effects of the PATHS intervention on educational outcomes. The key outcomes of interest are whether individuals attend and complete the academic high school track (Gymnasium), whether they obtain the Matura degree, which allows them to enrol in any university, and whether they are enroled in or graduated from university at age 24.

We observe students’ secondary school tracks at ages 13, 15, and 17 from administrative school data provided by the Department of Education of the Canton of Zurich. Some children leave the canton of Zurich and therefore disappear from the administrative data. We therefore complement the administrative records with self-reported tracking outcomes based on the z-proso survey.10 We observe whether students complete academic high school and enrol in university or graduate from university in the wave 9 z-proso survey administered at age 24.

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | N . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

| Educational outcomes | |||||

| Attending academic high school, age 13 | 1,589 | 0.157 | 0.364 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 15 | 1,535 | 0.202 | 0.402 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 17 | 1,305 | 0.261 | 0.439 | 0 | 1 |

| Completed academic high school, age 20 | 1,185 | 0.270 | 0.444 | 0 | 1 |

| Enrolled in university, age 20 | 1,178 | 0.167 | 0.373 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled in university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled or graduated university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.223 | 0.416 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child characteristics | |||||

| Age in 2005 | 1,238 | 7.033 | 0.396 | 5.699 | 8.494 |

| Swiss Citizenship | 1,238 | 0.599 | 0.490 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 1,675 | 0.481 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (teacher report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,348 | 1.246 | 0.989 | 0 | 4 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,348 | 0.541 | 0.815 | 0 | 4 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,348 | 0.217 | 0.405 | 0 | 2.500 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,348 | 0.871 | 0.762 | 0 | 4 |

| Overall aggression | 1,348 | 0.588 | 0.684 | 0 | 4 |

| Prosociality | 1,348 | 2.171 | 0.824 | 0 | 4 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (parent report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,229 | 1.212 | 0.646 | 0 | 3.778 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,229 | 0.966 | 0.621 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,229 | 0.296 | 0.326 | 0 | 2.800 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,229 | 0.704 | 0.464 | 0 | 2.556 |

| Overall aggression | 1,229 | 0.601 | 0.423 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Prosociality | 1,229 | 2.577 | 0.528 | 0.600 | 4 |

| Baseline parenting practices (parent report) | |||||

| Corporal punishment | 1,229 | 0.454 | 0.489 | 0 | 2.667 |

| Inconsistent discipline | 1,229 | 1.188 | 0.598 | 0 | 3.200 |

| Parental control and supervision | 1,229 | 3.686 | 0.328 | 2 | 4 |

| Parental involvement | 1,229 | 3.189 | 0.422 | 1.500 | 4 |

| Positive parenting | 1,229 | 3.215 | 0.514 | 1.200 | 4 |

| Baseline household characteristics | |||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,215 | 0.393 | 0.489 | 0 | 1 |

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,015 | 0.518 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother holds university degree | 1,215 | 0.160 | 0.367 | 0 | 1 |

| Father holds university degree | 1,015 | 0.249 | 0.433 | 0 | 1 |

| Single-parent household | 1,230 | 0.172 | 0.378 | 0 | 1 |

| Age mother in 2005 | 1,218 | 37.02 | 5.375 | 23 | 53 |

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 1,663 | 0.486 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother born in Switzerland | 1,219 | 0.423 | 0.494 | 0 | 1 |

| Family receives financial aid | 1,213 | 0.380 | 0.486 | 0 | 1 |

| Family reports financial problems | 1,216 | 0.178 | 0.382 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 1,132 | 86.31 | 48.71 | 12 | 270 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | N . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

| Educational outcomes | |||||

| Attending academic high school, age 13 | 1,589 | 0.157 | 0.364 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 15 | 1,535 | 0.202 | 0.402 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 17 | 1,305 | 0.261 | 0.439 | 0 | 1 |

| Completed academic high school, age 20 | 1,185 | 0.270 | 0.444 | 0 | 1 |

| Enrolled in university, age 20 | 1,178 | 0.167 | 0.373 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled in university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled or graduated university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.223 | 0.416 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child characteristics | |||||

| Age in 2005 | 1,238 | 7.033 | 0.396 | 5.699 | 8.494 |

| Swiss Citizenship | 1,238 | 0.599 | 0.490 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 1,675 | 0.481 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (teacher report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,348 | 1.246 | 0.989 | 0 | 4 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,348 | 0.541 | 0.815 | 0 | 4 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,348 | 0.217 | 0.405 | 0 | 2.500 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,348 | 0.871 | 0.762 | 0 | 4 |

| Overall aggression | 1,348 | 0.588 | 0.684 | 0 | 4 |

| Prosociality | 1,348 | 2.171 | 0.824 | 0 | 4 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (parent report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,229 | 1.212 | 0.646 | 0 | 3.778 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,229 | 0.966 | 0.621 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,229 | 0.296 | 0.326 | 0 | 2.800 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,229 | 0.704 | 0.464 | 0 | 2.556 |

| Overall aggression | 1,229 | 0.601 | 0.423 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Prosociality | 1,229 | 2.577 | 0.528 | 0.600 | 4 |

| Baseline parenting practices (parent report) | |||||

| Corporal punishment | 1,229 | 0.454 | 0.489 | 0 | 2.667 |

| Inconsistent discipline | 1,229 | 1.188 | 0.598 | 0 | 3.200 |

| Parental control and supervision | 1,229 | 3.686 | 0.328 | 2 | 4 |

| Parental involvement | 1,229 | 3.189 | 0.422 | 1.500 | 4 |

| Positive parenting | 1,229 | 3.215 | 0.514 | 1.200 | 4 |

| Baseline household characteristics | |||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,215 | 0.393 | 0.489 | 0 | 1 |

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,015 | 0.518 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother holds university degree | 1,215 | 0.160 | 0.367 | 0 | 1 |

| Father holds university degree | 1,015 | 0.249 | 0.433 | 0 | 1 |

| Single-parent household | 1,230 | 0.172 | 0.378 | 0 | 1 |

| Age mother in 2005 | 1,218 | 37.02 | 5.375 | 23 | 53 |

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 1,663 | 0.486 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother born in Switzerland | 1,219 | 0.423 | 0.494 | 0 | 1 |

| Family receives financial aid | 1,213 | 0.380 | 0.486 | 0 | 1 |

| Family reports financial problems | 1,216 | 0.178 | 0.382 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 1,132 | 86.31 | 48.71 | 12 | 270 |

Notes: This table shows descriptive statistics for the variables used in our analysis. SD stands for standard deviation.

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | N . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

| Educational outcomes | |||||

| Attending academic high school, age 13 | 1,589 | 0.157 | 0.364 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 15 | 1,535 | 0.202 | 0.402 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 17 | 1,305 | 0.261 | 0.439 | 0 | 1 |

| Completed academic high school, age 20 | 1,185 | 0.270 | 0.444 | 0 | 1 |

| Enrolled in university, age 20 | 1,178 | 0.167 | 0.373 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled in university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled or graduated university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.223 | 0.416 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child characteristics | |||||

| Age in 2005 | 1,238 | 7.033 | 0.396 | 5.699 | 8.494 |

| Swiss Citizenship | 1,238 | 0.599 | 0.490 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 1,675 | 0.481 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (teacher report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,348 | 1.246 | 0.989 | 0 | 4 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,348 | 0.541 | 0.815 | 0 | 4 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,348 | 0.217 | 0.405 | 0 | 2.500 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,348 | 0.871 | 0.762 | 0 | 4 |

| Overall aggression | 1,348 | 0.588 | 0.684 | 0 | 4 |

| Prosociality | 1,348 | 2.171 | 0.824 | 0 | 4 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (parent report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,229 | 1.212 | 0.646 | 0 | 3.778 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,229 | 0.966 | 0.621 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,229 | 0.296 | 0.326 | 0 | 2.800 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,229 | 0.704 | 0.464 | 0 | 2.556 |

| Overall aggression | 1,229 | 0.601 | 0.423 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Prosociality | 1,229 | 2.577 | 0.528 | 0.600 | 4 |

| Baseline parenting practices (parent report) | |||||

| Corporal punishment | 1,229 | 0.454 | 0.489 | 0 | 2.667 |

| Inconsistent discipline | 1,229 | 1.188 | 0.598 | 0 | 3.200 |

| Parental control and supervision | 1,229 | 3.686 | 0.328 | 2 | 4 |

| Parental involvement | 1,229 | 3.189 | 0.422 | 1.500 | 4 |

| Positive parenting | 1,229 | 3.215 | 0.514 | 1.200 | 4 |

| Baseline household characteristics | |||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,215 | 0.393 | 0.489 | 0 | 1 |

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,015 | 0.518 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother holds university degree | 1,215 | 0.160 | 0.367 | 0 | 1 |

| Father holds university degree | 1,015 | 0.249 | 0.433 | 0 | 1 |

| Single-parent household | 1,230 | 0.172 | 0.378 | 0 | 1 |

| Age mother in 2005 | 1,218 | 37.02 | 5.375 | 23 | 53 |

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 1,663 | 0.486 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother born in Switzerland | 1,219 | 0.423 | 0.494 | 0 | 1 |

| Family receives financial aid | 1,213 | 0.380 | 0.486 | 0 | 1 |

| Family reports financial problems | 1,216 | 0.178 | 0.382 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 1,132 | 86.31 | 48.71 | 12 | 270 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | N . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

| Educational outcomes | |||||

| Attending academic high school, age 13 | 1,589 | 0.157 | 0.364 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 15 | 1,535 | 0.202 | 0.402 | 0 | 1 |

| Attending academic high school, age 17 | 1,305 | 0.261 | 0.439 | 0 | 1 |

| Completed academic high school, age 20 | 1,185 | 0.270 | 0.444 | 0 | 1 |

| Enrolled in university, age 20 | 1,178 | 0.167 | 0.373 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled in university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0 | 1 |

| Enroled or graduated university, age 24 | 1,158 | 0.223 | 0.416 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child characteristics | |||||

| Age in 2005 | 1,238 | 7.033 | 0.396 | 5.699 | 8.494 |

| Swiss Citizenship | 1,238 | 0.599 | 0.490 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 1,675 | 0.481 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (teacher report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,348 | 1.246 | 0.989 | 0 | 4 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,348 | 0.541 | 0.815 | 0 | 4 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,348 | 0.217 | 0.405 | 0 | 2.500 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,348 | 0.871 | 0.762 | 0 | 4 |

| Overall aggression | 1,348 | 0.588 | 0.684 | 0 | 4 |

| Prosociality | 1,348 | 2.171 | 0.824 | 0 | 4 |

| Baseline child socio-emotional skills (parent report) | |||||

| ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 1,229 | 1.212 | 0.646 | 0 | 3.778 |

| Opposition and defiance | 1,229 | 0.966 | 0.621 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 1,229 | 0.296 | 0.326 | 0 | 2.800 |

| Anxiety and depressivity | 1,229 | 0.704 | 0.464 | 0 | 2.556 |

| Overall aggression | 1,229 | 0.601 | 0.423 | 0 | 2.750 |

| Prosociality | 1,229 | 2.577 | 0.528 | 0.600 | 4 |

| Baseline parenting practices (parent report) | |||||

| Corporal punishment | 1,229 | 0.454 | 0.489 | 0 | 2.667 |

| Inconsistent discipline | 1,229 | 1.188 | 0.598 | 0 | 3.200 |

| Parental control and supervision | 1,229 | 3.686 | 0.328 | 2 | 4 |

| Parental involvement | 1,229 | 3.189 | 0.422 | 1.500 | 4 |

| Positive parenting | 1,229 | 3.215 | 0.514 | 1.200 | 4 |

| Baseline household characteristics | |||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,215 | 0.393 | 0.489 | 0 | 1 |

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | 1,015 | 0.518 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother holds university degree | 1,215 | 0.160 | 0.367 | 0 | 1 |

| Father holds university degree | 1,015 | 0.249 | 0.433 | 0 | 1 |

| Single-parent household | 1,230 | 0.172 | 0.378 | 0 | 1 |

| Age mother in 2005 | 1,218 | 37.02 | 5.375 | 23 | 53 |

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 1,663 | 0.486 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother born in Switzerland | 1,219 | 0.423 | 0.494 | 0 | 1 |

| Family receives financial aid | 1,213 | 0.380 | 0.486 | 0 | 1 |

| Family reports financial problems | 1,216 | 0.178 | 0.382 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 1,132 | 86.31 | 48.71 | 12 | 270 |

Notes: This table shows descriptive statistics for the variables used in our analysis. SD stands for standard deviation.

Table 1 shows that 16% of the participants attend academic high school at age 13, right after tracking has taken place. This number increases to 20% at age 15 and 26% at age 17.11 Twenty-seven percent of children complete academic high school, and 17% are enroled in university at age 20. At age 24, 22% have graduated from university or are still enroled in university.

Baseline measures: Table 1 shows characteristics of children and parents measured at the baseline, that is, in the year before the start of the intervention. At this time, children are, on average, seven-years old. Forty-eight percent are girls. Our sample comes from a diverse population: only 60% are Swiss, 90% were born in Switzerland, and only 49% of mothers are Swiss. Seventeen percent of households are single-parent households. About 39% of mothers have completed at least academic high school (Gymnasium), and 16% hold a university degree. Fathers are slightly more educated than mothers, with 52% having completed Gymnasium or other types of higher education and 25% holding a university degree. The average family household income is USD 86,000 per year; 38% of families are entitled to state funded financial aid, and 18% report financial problems at the baseline. Our data also contain detailed baseline measures of child behaviour assessed through the Social Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ; Tremblay et al., 1991; Murray et al., 2019) and the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton et al., 1996).

5. EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

5.1 Empirical model

We aim to estimate the treatment effect of the PATHS intervention on educational outcomes. Equation (1) shows our main empirical model:

where

Vector

We estimate equation (1) using linear probability models and cluster standard errors at the school level. We additionally provide p-values based on randomization inference with 10,000 repetitions following Young (2019).

5.2 Balancing tests

The identifying assumption of our empirical strategy relies on the random assignment of children to the treatment status. To verify this assumption, we test whether baseline characteristics predict treatment status. In particular, we regress treatment status on each of the pre-treatment characteristics separately. We use all available characteristics on child and family demographics and measures for socio-emotional skills, and we estimate a total of fifty-six regressions.

Table 2 summarizes the balancing tests. Column (1) shows the number of statistically significant coefficients we obtain when regressing the indicator for treatment status (

| . | (1) . | (2) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | Number of . | Expectation under random . |

| . | balancing tests . | assignment . |

| Total number of balancing tests | 56 | |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.01 | 1 | 0.560 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.05 | 2 | 2.800 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.1 | 5 | 5.600 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | Number of . | Expectation under random . |

| . | balancing tests . | assignment . |

| Total number of balancing tests | 56 | |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.01 | 1 | 0.560 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.05 | 2 | 2.800 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.1 | 5 | 5.600 |

Notes: This table summarizes the results of our balancing tests. To test random assignment, we regress treatment status on baseline characteristics. We run a separate linear probability model for each baseline characteristic. Table 3 shows a detailed list of all baseline characteristics and individual point estimates. All regressions include strata fixed effects for the level of randomization. Standard errors are clustered at the school level. Column (1) reports the total number of balancing tests and the number of statistically significant tests for different levels of significance. Column (2) reports the number of coefficients we would expect to be statistically significant due to chance under random assignment.

| . | (1) . | (2) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | Number of . | Expectation under random . |

| . | balancing tests . | assignment . |

| Total number of balancing tests | 56 | |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.01 | 1 | 0.560 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.05 | 2 | 2.800 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.1 | 5 | 5.600 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | Number of . | Expectation under random . |

| . | balancing tests . | assignment . |

| Total number of balancing tests | 56 | |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.01 | 1 | 0.560 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.05 | 2 | 2.800 |

| Number of tests significant with p < 0.1 | 5 | 5.600 |

Notes: This table summarizes the results of our balancing tests. To test random assignment, we regress treatment status on baseline characteristics. We run a separate linear probability model for each baseline characteristic. Table 3 shows a detailed list of all baseline characteristics and individual point estimates. All regressions include strata fixed effects for the level of randomization. Standard errors are clustered at the school level. Column (1) reports the total number of balancing tests and the number of statistically significant tests for different levels of significance. Column (2) reports the number of coefficients we would expect to be statistically significant due to chance under random assignment.

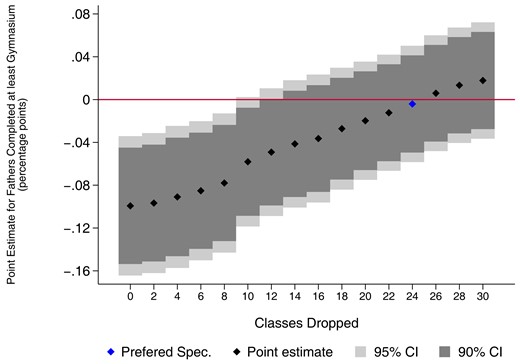

Table 3 provides a closer look at unbalanced variables by reporting point estimates from all fifty-six balancing regressions. The analysis reveals a substantial and significant imbalance (p < 0.01) in fathers’ education levels between the treatment and the control group. Given that parental education is a key determinant of children's educational outcomes, this imbalance deserves careful consideration. Children receiving the PATHS intervention come from families with, on average, less-educated parents. Treated children are about 10 percentage points less likely to have a father that holds at least an academic high school degree. This imbalance in fathers’ education levels will make it harder for us to identify effects of the intervention if the treatment affects children's educational outcomes positively. Without accounting for this imbalance, we would underestimate treatment effects of the PATHS programme.

| . | (1) . | . | (2) . | . | (3) . | . | (4) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and household characteristics . | PATHS . | SBQ (parent report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (teacher report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (child report) . | PATHS . |

| Age in 2005 | −0.013 | Prosociality | 0.004 | Prosociality | 0.056** | Prosociality | −0.004 |

| (0.042) | (0.013) | (0.027) | (0.016) | ||||

| Female | 0.036* | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.035 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 |

| (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.013) | ||||

| Swiss Citizenship | 0.036 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | −0.004 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.035 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.014 |

| (0.045) | (0.012) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother holds university degree | −0.049 | Opposition and defiance | −0.022* | Opposition and defiance | 0.029 | Opposition and defiance | 0.013 |

| (0.045) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.013) | ||||

| Father holds university degree | −0.073 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.000 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.008 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | −0.009 |

| (0.044) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.011) | ||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.049 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | −0.016 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.020 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.005 |

| (0.035) | (0.013) | (0.022) | (0.012) | ||||

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.099*** | Indirect aggression | 0.016 | Indirect aggression | 0.029 | Indirect aggression | 0.022 |

| (0.032) | (0.013) | (0.020) | (0.014) | ||||

| Single-parent household | 0.004 | Reactive aggression | 0.000 | Reactive aggression | 0.018 | Reactive aggression | 0.002 |

| (0.029) | (0.012) | (0.026) | (0.013) | ||||

| Age mother in 2005 | 0.003 | Physical aggression | −0.005 | Physical aggression | 0.001 | Physical aggression | 0.009 |

| (0.003) | (0.015) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | −0.008 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.023* |

| (0.039) | (0.013) | (0.021) | (0.012) | ||||

| Mother born in Switzerland | 0.017 | Overall aggression | −0.005 | Overall aggression | 0.017 | Overall aggression | 0.013 |

| (0.036) | (0.014) | (0.023) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family receives financial aid | −0.031 | Overall externalizing behaviour | −0.009 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.029 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.013 |

| (0.028) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family reports financial problems | −0.009 | Overall behaviour score 1 | −0.002 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.017 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.016 |

| (0.043) | (0.014) | (0.025) | (0.015) | ||||

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 0.000 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.010 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.011 | Overall behaviour score 2 | 0.011 |

| (0.000) | (0.014) | (0.024) | (0.015) |

| . | (1) . | . | (2) . | . | (3) . | . | (4) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and household characteristics . | PATHS . | SBQ (parent report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (teacher report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (child report) . | PATHS . |

| Age in 2005 | −0.013 | Prosociality | 0.004 | Prosociality | 0.056** | Prosociality | −0.004 |

| (0.042) | (0.013) | (0.027) | (0.016) | ||||

| Female | 0.036* | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.035 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 |

| (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.013) | ||||

| Swiss Citizenship | 0.036 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | −0.004 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.035 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.014 |

| (0.045) | (0.012) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother holds university degree | −0.049 | Opposition and defiance | −0.022* | Opposition and defiance | 0.029 | Opposition and defiance | 0.013 |

| (0.045) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.013) | ||||

| Father holds university degree | −0.073 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.000 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.008 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | −0.009 |

| (0.044) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.011) | ||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.049 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | −0.016 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.020 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.005 |

| (0.035) | (0.013) | (0.022) | (0.012) | ||||

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.099*** | Indirect aggression | 0.016 | Indirect aggression | 0.029 | Indirect aggression | 0.022 |

| (0.032) | (0.013) | (0.020) | (0.014) | ||||

| Single-parent household | 0.004 | Reactive aggression | 0.000 | Reactive aggression | 0.018 | Reactive aggression | 0.002 |

| (0.029) | (0.012) | (0.026) | (0.013) | ||||

| Age mother in 2005 | 0.003 | Physical aggression | −0.005 | Physical aggression | 0.001 | Physical aggression | 0.009 |

| (0.003) | (0.015) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | −0.008 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.023* |

| (0.039) | (0.013) | (0.021) | (0.012) | ||||

| Mother born in Switzerland | 0.017 | Overall aggression | −0.005 | Overall aggression | 0.017 | Overall aggression | 0.013 |

| (0.036) | (0.014) | (0.023) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family receives financial aid | −0.031 | Overall externalizing behaviour | −0.009 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.029 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.013 |

| (0.028) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family reports financial problems | −0.009 | Overall behaviour score 1 | −0.002 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.017 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.016 |

| (0.043) | (0.014) | (0.025) | (0.015) | ||||

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 0.000 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.010 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.011 | Overall behaviour score 2 | 0.011 |

| (0.000) | (0.014) | (0.024) | (0.015) |

Notes: This table shows the coefficients from fifty-six separate ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions testing whether a characteristic predicts treatment status. The treatment indicator PATHS is regressed on one baseline variable. Baseline variables include all available child, parental, and household characteristics and baseline child SBQ measures. All models include strata fixed effects for the level of randomization. Robust standard errors clustered at the school level are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

| . | (1) . | . | (2) . | . | (3) . | . | (4) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and household characteristics . | PATHS . | SBQ (parent report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (teacher report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (child report) . | PATHS . |

| Age in 2005 | −0.013 | Prosociality | 0.004 | Prosociality | 0.056** | Prosociality | −0.004 |

| (0.042) | (0.013) | (0.027) | (0.016) | ||||

| Female | 0.036* | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.035 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 |

| (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.013) | ||||

| Swiss Citizenship | 0.036 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | −0.004 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.035 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.014 |

| (0.045) | (0.012) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother holds university degree | −0.049 | Opposition and defiance | −0.022* | Opposition and defiance | 0.029 | Opposition and defiance | 0.013 |

| (0.045) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.013) | ||||

| Father holds university degree | −0.073 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.000 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.008 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | −0.009 |

| (0.044) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.011) | ||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.049 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | −0.016 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.020 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.005 |

| (0.035) | (0.013) | (0.022) | (0.012) | ||||

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.099*** | Indirect aggression | 0.016 | Indirect aggression | 0.029 | Indirect aggression | 0.022 |

| (0.032) | (0.013) | (0.020) | (0.014) | ||||

| Single-parent household | 0.004 | Reactive aggression | 0.000 | Reactive aggression | 0.018 | Reactive aggression | 0.002 |

| (0.029) | (0.012) | (0.026) | (0.013) | ||||

| Age mother in 2005 | 0.003 | Physical aggression | −0.005 | Physical aggression | 0.001 | Physical aggression | 0.009 |

| (0.003) | (0.015) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | −0.008 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.023* |

| (0.039) | (0.013) | (0.021) | (0.012) | ||||

| Mother born in Switzerland | 0.017 | Overall aggression | −0.005 | Overall aggression | 0.017 | Overall aggression | 0.013 |

| (0.036) | (0.014) | (0.023) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family receives financial aid | −0.031 | Overall externalizing behaviour | −0.009 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.029 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.013 |

| (0.028) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family reports financial problems | −0.009 | Overall behaviour score 1 | −0.002 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.017 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.016 |

| (0.043) | (0.014) | (0.025) | (0.015) | ||||

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 0.000 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.010 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.011 | Overall behaviour score 2 | 0.011 |

| (0.000) | (0.014) | (0.024) | (0.015) |

| . | (1) . | . | (2) . | . | (3) . | . | (4) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and household characteristics . | PATHS . | SBQ (parent report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (teacher report) . | PATHS . | SBQ (child report) . | PATHS . |

| Age in 2005 | −0.013 | Prosociality | 0.004 | Prosociality | 0.056** | Prosociality | −0.004 |

| (0.042) | (0.013) | (0.027) | (0.016) | ||||

| Female | 0.036* | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.035 | Anxiety and depressivity | 0.009 |

| (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.013) | ||||

| Swiss Citizenship | 0.036 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | −0.004 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.035 | ADHD symptoms (disruptiveness and impulsiveness) | 0.014 |

| (0.045) | (0.012) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother holds university degree | −0.049 | Opposition and defiance | −0.022* | Opposition and defiance | 0.029 | Opposition and defiance | 0.013 |

| (0.045) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.013) | ||||

| Father holds university degree | −0.073 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.000 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | 0.008 | Non-aggressive conduct disorder | −0.009 |

| (0.044) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.011) | ||||

| Mother completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.049 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | −0.016 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.020 | Non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour | 0.005 |

| (0.035) | (0.013) | (0.022) | (0.012) | ||||

| Father completed at least Gymnasium degree | −0.099*** | Indirect aggression | 0.016 | Indirect aggression | 0.029 | Indirect aggression | 0.022 |

| (0.032) | (0.013) | (0.020) | (0.014) | ||||

| Single-parent household | 0.004 | Reactive aggression | 0.000 | Reactive aggression | 0.018 | Reactive aggression | 0.002 |

| (0.029) | (0.012) | (0.026) | (0.013) | ||||

| Age mother in 2005 | 0.003 | Physical aggression | −0.005 | Physical aggression | 0.001 | Physical aggression | 0.009 |

| (0.003) | (0.015) | (0.021) | (0.014) | ||||

| Mother Swiss Citizenship | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | −0.008 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.029 | Proactive aggression and dominance | 0.023* |

| (0.039) | (0.013) | (0.021) | (0.012) | ||||

| Mother born in Switzerland | 0.017 | Overall aggression | −0.005 | Overall aggression | 0.017 | Overall aggression | 0.013 |

| (0.036) | (0.014) | (0.023) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family receives financial aid | −0.031 | Overall externalizing behaviour | −0.009 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.029 | Overall externalizing behaviour | 0.013 |

| (0.028) | (0.013) | (0.024) | (0.014) | ||||

| Family reports financial problems | −0.009 | Overall behaviour score 1 | −0.002 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.017 | Overall behaviour score 1 | 0.016 |

| (0.043) | (0.014) | (0.025) | (0.015) | ||||

| Household income (in 1000 USDs) | 0.000 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.010 | Overall behaviour score 2 | −0.011 | Overall behaviour score 2 | 0.011 |

| (0.000) | (0.014) | (0.024) | (0.015) |

Notes: This table shows the coefficients from fifty-six separate ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions testing whether a characteristic predicts treatment status. The treatment indicator PATHS is regressed on one baseline variable. Baseline variables include all available child, parental, and household characteristics and baseline child SBQ measures. All models include strata fixed effects for the level of randomization. Robust standard errors clustered at the school level are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

To provide a better understanding of the initial imbalance and its consequences for our results, we conduct a series of exercises. In Section 6.2, we show how different sets of control variables affect our results. We highlight that we need to control for unbalanced parental education to obtain unbiased treatment effects. In Section 6.2, we further conduct a permutation exercise that highlights that creating a balanced estimation sample is an alternative way to obtain unbiased estimates that does not require the inclusion of control variables. Overall, our analyses highlight that it is essential to account for the initial imbalance in the sample to obtain unbiased results.

6. RESULTS

In this section, we provide the main results of our analysis on the impact of the PATHS curriculum on educational careers. We also provide a series of sensitivity analyses and test whether results are driven by selective attrition and estimate treatment effects for different subgroups.

6.1 Main results

Table 4 shows estimates of the PATHS treatment effect on education trajectories from equation (1). The dependent variable in column (1) is an indicator for academic high school attendance at age 13, immediately after tracking has occurred. The dependent variable in column (2) is an indicator for academic high school completion at age 20. In column (3), the dependent variable is an indicator for university enrolment or graduation at age 24.

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Initial tracking . | Academic . | University . |

| . | into academic . | high school . | enrolment or . |

| . | high school . | completion . | graduation . |

| PATHS treatment | 0.044** | 0.071*** | 0.065*** |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.022) | |

| Randomization inference p-value | 0.054 | 0.016 | 0.027 |

| Observations | 1,011 | 837 | 815 |

| R2 | 0.303 | 0.364 | 0.249 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.199 | 0.308 | 0.252 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Initial tracking . | Academic . | University . |

| . | into academic . | high school . | enrolment or . |

| . | high school . | completion . | graduation . |

| PATHS treatment | 0.044** | 0.071*** | 0.065*** |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.022) | |

| Randomization inference p-value | 0.054 | 0.016 | 0.027 |

| Observations | 1,011 | 837 | 815 |

| R2 | 0.303 | 0.364 | 0.249 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.199 | 0.308 | 0.252 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

Notes: This table shows the treatment effect of the PATHS intervention on initial tracking into academic high school at age 13, academic high school completion at age 20, and university enrolment or graduation at age 24. All outcomes are indicator variables and the specifications are estimated using linear probability models using controls for baseline child and household characteristics. Child controls include the age and gender of the child, having Swiss citizenship, measures for anxiety and depressivity, ADHD, non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour, non-aggressive conduct disorder, opposition and defiance, prosociality, four measures of aggressive behaviour, and four measures of overall behaviour. Household controls include household income, mother's and father's education level (including an indicator for missing information), age of the mother, indicator variables for the mother's having Swiss citizenship and being born in Switzerland, and indicator variables for a single-parent household, a household that received financial aid, and a household that experienced financial problems. The outcome initial tracking into academic high school is based on administrative data. The outcomes academic high school completion and university enrolment or graduation are self-reported. All models include strata fixed effects for the level of randomization. The table also shows p-values based on randomization inference with 10,000 replications. Robust standard errors clustered at the school level are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Initial tracking . | Academic . | University . |

| . | into academic . | high school . | enrolment or . |

| . | high school . | completion . | graduation . |

| PATHS treatment | 0.044** | 0.071*** | 0.065*** |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.022) | |

| Randomization inference p-value | 0.054 | 0.016 | 0.027 |

| Observations | 1,011 | 837 | 815 |

| R2 | 0.303 | 0.364 | 0.249 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.199 | 0.308 | 0.252 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Initial tracking . | Academic . | University . |

| . | into academic . | high school . | enrolment or . |

| . | high school . | completion . | graduation . |

| PATHS treatment | 0.044** | 0.071*** | 0.065*** |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.022) | |

| Randomization inference p-value | 0.054 | 0.016 | 0.027 |

| Observations | 1,011 | 837 | 815 |

| R2 | 0.303 | 0.364 | 0.249 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.199 | 0.308 | 0.252 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

Notes: This table shows the treatment effect of the PATHS intervention on initial tracking into academic high school at age 13, academic high school completion at age 20, and university enrolment or graduation at age 24. All outcomes are indicator variables and the specifications are estimated using linear probability models using controls for baseline child and household characteristics. Child controls include the age and gender of the child, having Swiss citizenship, measures for anxiety and depressivity, ADHD, non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour, non-aggressive conduct disorder, opposition and defiance, prosociality, four measures of aggressive behaviour, and four measures of overall behaviour. Household controls include household income, mother's and father's education level (including an indicator for missing information), age of the mother, indicator variables for the mother's having Swiss citizenship and being born in Switzerland, and indicator variables for a single-parent household, a household that received financial aid, and a household that experienced financial problems. The outcome initial tracking into academic high school is based on administrative data. The outcomes academic high school completion and university enrolment or graduation are self-reported. All models include strata fixed effects for the level of randomization. The table also shows p-values based on randomization inference with 10,000 replications. Robust standard errors clustered at the school level are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table 4 shows positive and statistically significant treatment effects across all educational outcomes. The PATHS programme leads to a 4.4 percentage point increase in the likelihood of children attending an academic high school at age 13, immediately after tracking. This effect is economically significant, as it corresponds to a 22% increase compared to the control group mean. The positive impact persists over time. By age 20, attending PATHS increases the likelihood of completing academic high school by 7.1 percentage points, representing a 23% increase over the completion rate of the control group. Furthermore, the treatment effect of PATHS remains visible for higher education. At age 24, PATHS increases the likelihood of attending university or having already graduated from university by 6.5 percentage points (26%).12

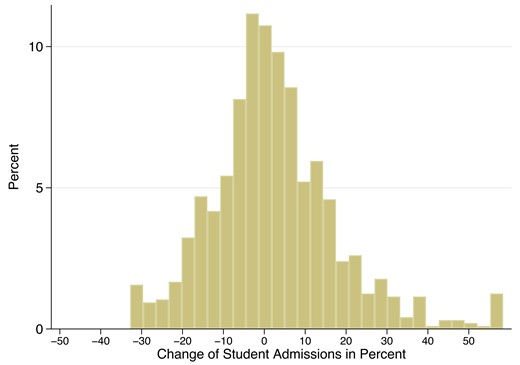

The results presented in Table 4 suggest that the PATHS treatment effect is fairly persistent over time. Many students, however, move between tracks during their career. Supplementary Figure A1 shows a flowchart that illustrates how students switch between school tracks over time, which highlights substantial mobility. About 35% of students who graduate from academic high school were initially not admitted to this track at age 13. Similarly, 38% of students that are enroled in or have graduated from university at age 24 did not attend the academic high school track at age 13. This evidence calls for a closer examination of how treatment effects evolve over time.

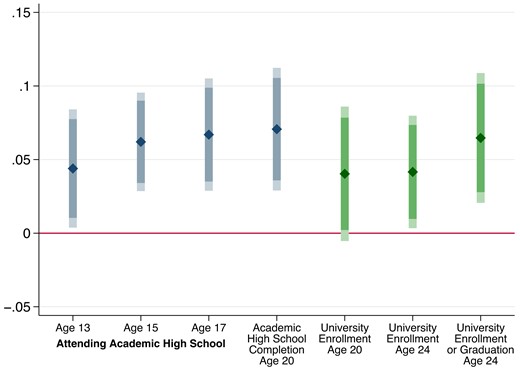

Figure 2 shows how the PATHS treatment effect evolves over time using data from all available waves. The figure displays the treatment effects on academic high school enrolment at ages 13, 15, and 17, as well as high school completion and university enrolment at age 20, and university enrolment or graduation at age 24. All the point estimates in Figure 2 are positive and statistically significant. The PATHS treatment effect slightly increases over time. Notably, the mean of the dependent variables also increases over time with the relative treatment effect being fairly constant over time.13,14

Main results—treatment effects on educational outcomes Notes: This figure shows the treatment effect of the PATHS intervention on attending academic high school at ages 13, 15, and 17 as well as academic high school completion at age 20, university enrolment at ages 20 and 24, and university enrolment or graduation at age 24. All outcomes are indicator variables and the specifications are estimated using linear probability models using controls for baseline child and household characteristics. Child controls include the age and gender of the child, having Swiss citizenship, measures for anxiety and depressivity, ADHD, non-aggressive externalizing problem behaviour, non-aggressive conduct disorder, opposition and defiance, prosociality, four measures of aggressive behaviour, and four measures of overall behaviour. Household controls include household income, mother's and father's education level, age of the mother, indicator variables for the mother's having a Swiss citizenship and being born in Switzerland, and indicator variables for a single-parent household, a household that received financial aid, and a household that experienced financial problems. The outcomes attending academic high school at ages 13, 15, and 17 are based on administrative data. The outcomes of academic high school completion and university enrolment at age 20, university enrolment at age 24, and university enrolment or graduation are self-reported. All models include strata fixed effects for the level of randomization. Each point estimate is shown with the respective 90% and 95% confidence intervals calculated based on standard errors clustered at the school level.

Overall, we observe large and economically significant effects. In the average class in our sample, five out of twenty-eight children attend university at age 20. The size of the treatment effect implies that one additional child—six instead of five—will attend university due to the intervention. We discuss our effect sizes and how they compare to other childhood interventions in Section 9.

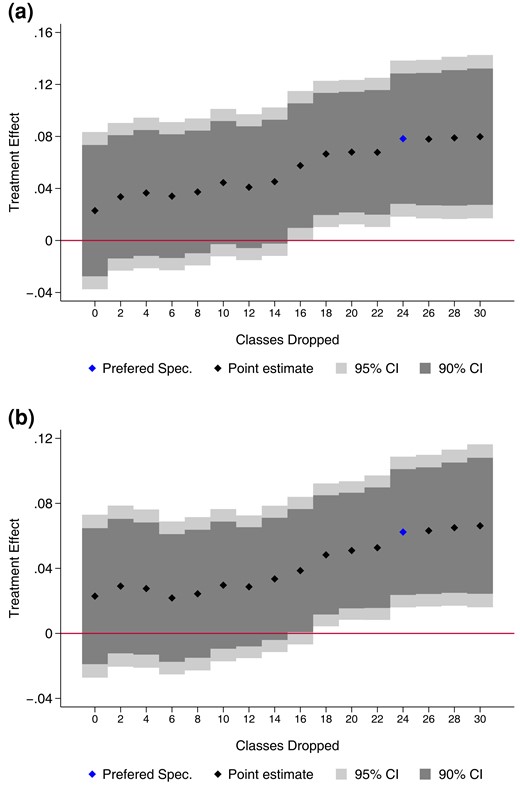

6.2 Sensitivity analysis—imbalanced treatment and control groups

One potentially important concern for the interpretation of our results comes from the imbalance in fathers’ education between the treatment and control groups. To assess how much this initial imbalance affects our estimates, we estimate treatment effects with and without controls for the initial imbalance in Table 5. Panel A reports results without any control variables except the randomization strata. Panel B reports results with controls for parental education to account for the imbalance between the treatment and control groups at the baseline. Panel C reports results from the model that additionally include the full set of baseline control variables.

Treatment effects of PATHS on educational outcomes in different specifications

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Initial tracking into . | Academic high . | University enrolment . |

| . | academic high school . | school completion . | or graduation . |

| Panel A: no controls | |||

| PATHS treatment | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| (0.018) | (0.030) | (0.025) | |

| Observations | 1,589 | 1,185 | 1,158 |

| R2 | 0.072 | 0.107 | 0.075 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.163 | 0.269 | 0.222 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| Panel B: parental education controls | |||

| PATHS treatment | 0.023* | 0.051** | 0.039** |

| (0.013) | (0.021) | (0.020) | |

| Observations | 1,589 | 1,185 | 1,158 |

| R2 | 0.224 | 0.265 | 0.188 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.163 | 0.269 | 0.222 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| Panel C: full controls | |||

| PATHS treatment | 0.044** | 0.071*** | 0.065*** |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.022) | |

| Observations | 1,011 | 837 | 815 |

| R2 | 0.303 | 0.364 | 0.249 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.199 | 0.308 | 0.252 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Initial tracking into . | Academic high . | University enrolment . |

| . | academic high school . | school completion . | or graduation . |

| Panel A: no controls | |||

| PATHS treatment | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| (0.018) | (0.030) | (0.025) | |

| Observations | 1,589 | 1,185 | 1,158 |

| R2 | 0.072 | 0.107 | 0.075 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.163 | 0.269 | 0.222 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| Panel B: parental education controls | |||

| PATHS treatment | 0.023* | 0.051** | 0.039** |

| (0.013) | (0.021) | (0.020) | |

| Observations | 1,589 | 1,185 | 1,158 |

| R2 | 0.224 | 0.265 | 0.188 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.163 | 0.269 | 0.222 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| Panel C: full controls | |||

| PATHS treatment | 0.044** | 0.071*** | 0.065*** |

| (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.022) | |

| Observations | 1,011 | 837 | 815 |

| R2 | 0.303 | 0.364 | 0.249 |

| Control group mean dependent variable | 0.199 | 0.308 | 0.252 |

| Child age | 13 | 20 | 24 |

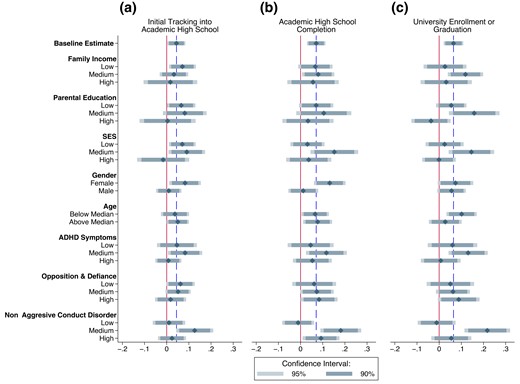

| Panel wave | 5 | 8 | 9 |