-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marina Kunstreich, Desiree Dunstheimer, Pascal Mier, Paul-Martin Holterhus, Stefan A Wudy, Angela Huebner, Antje Redlich, Michaela Kuhlen, The Endocrine Phenotype Induced by Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumors Is Age- and Sex-Dependent, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 109, Issue 8, August 2024, Pages 2053–2060, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae073

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Adrenocortical carcinomas are very rare malignancies in childhood associated with poor outcome in advanced disease. Most adrenocortical tumors (ACT) are functional, causing signs and symptoms of adrenal hormone excess. In most studies, endocrine manifestations were reported 4 to 6 months prior to diagnosis.

We sought to extend knowledge on endocrine manifestations with regard to age and sex to facilitate early diagnosis.

We retrospectively analyzed features of adrenal hormone excess in children and adolescents with ACT registered with the GPOH-MET studies between 1997 and 2022. Stage of puberty was defined as prepubertal in females < 8 years of age and males < 9 years.

By December 2022, 155 patients (110 female, 45 male) with data on endocrine manifestations had been reported. Median age at ACT diagnosis was 4.2 years [0.1-17.8], median interval from first symptoms was 4.2 months [0-90.7]. In 63 girls of prepubertal age, the most frequently reported manifestations were pubarche (68.3%), clitoral hypertrophy (49.2%), and weight gain (31.7%); in 47 pubertal female patients, the most frequent manifestations were excessive pubic hair (46.8%), acne (36.2%), and hypertension (36.2%). Leading symptoms in 34 boys of prepubertal age were pubarche (55.9%), penile growth (47.1%), and acne (32.4%), while in 11 pubertal male patients, leading symptoms were weight gain (45.5%), hypertension (36.4%), excessive pubic hair (27.3%), and cushingoid appearance (27.3%). In pubertal patients, symptoms of androgen excess were mainly unrecognized as part of pubertal development, while symptoms of Cushing syndrome were more frequently apparent.

The endocrine phenotype induced by pediatric ACT is age- and sex-dependent.

Adrenocortical tumors (ACTs) encompassing adrenocortical adenoma (ACA), tumors of undetermined malignant potential (ACx), and carcinoma (ACC) are very rare endocrine neoplasms in children and adolescents (1-4). Pediatric ACT present with considerable clinical heterogeneity and ambiguous biological behavior impeding proper and timely diagnosis. Around half of pediatric patients are diagnosed with locally advanced tumors; in 50% of these patients, disease recurs even after complete tumor resection (5-8). Patients with metastatic disease have a dismal outcome, with an overall survival of less than 20% (9-11). The mainstay of therapy is complete surgical resection (12). Effective systemic therapies for children and adolescents with advanced and metastatic disease are still missing (13). Hence, identifying children and adolescents with ACT as early as possible is of crucial importance. However, a median symptomatic interval of 3 to 8 months prior to diagnosis was reported (9, 14, 15).

About 80% to 90% of pediatric ACT are functional, causing signs and symptoms of adrenal hormone excess (14, 16). Nonfunctional tumors usually present as abdominal masses or less frequently as incidental findings (17, 18).

In published studies of children and adolescents with ACT, the phenotypic presentation of adrenal hormone excess was classified into virilization (55.1%-61.0%), virilization combined with Cushing syndrome (29.2%-39.2%), and Cushing syndrome only (5.0%-53.5%) (19-21). These overarching groups of symptoms were reported to be associated with tumor stage (16). Virilization was more frequently reported in localized tumors, while Cushing syndrome was more frequently reported in cases with advanced and metastatic disease. Symptoms of adrenal hormone excess were furthermore associated with outcome (22). Being affected by Cushing syndrome resulted in worse outcome compared with being not affected by Cushing syndrome. Non-secreting tumors were also associated with poor outcome. Notably, Cushing syndrome and non-secreting tumors were more frequently diagnosed in older children (20).

Here, we seek to extend our knowledge on and deepen our understanding of signs and symptoms of adrenal hormone excess in children and adolescents with ACT. To this end, we assessed the spectrum of endocrine manifestations in children and adolescents with ACT registered with the German Paediatric Oncology Haematology-Malignant Endocrine Tumour (GPOH-MET) studies since 1997. We asked if the endocrine phenotype was associated with age, sex, and tumor dignity and if there were features that should raise attention.

Methods

The GPOH-MET studies prospectively registered children and adolescents < 18 years of age (subsequently referred to as pediatric) with ACT. Patients were reported by the treating physicians in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland upon informed consent of patients, parents, and legal guardians, as appropriate. We included patients with information on endocrine manifestations at diagnosis of ACT, registered between 1997 and 2022.

The GPOH-MET 97 protocol and registry were approved by the ethics committees of the University of Luebeck (Approval number 97125) and Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg (Approval number 174/12), Germany.

Demographic-, endocrine-, and tumor-related characteristics were collected using original source data. Frequencies were related to cases with recorded data. On the case report form, endocrine manifestations were categorized into virilization, Cushing syndrome, hypertension, abdominal pain, other symptoms, and no symptoms. Details on endocrine manifestations, including premature axillary and/or pubic hair (herein referred to as pubarche), clitoral hypertrophy, menstrual disorder, hirsutism, penile growth, deepening of voice, tall stature, accelerated bone age, increased muscle strength, alopecia, acne, sweat odor, greasy hair, weight gain/obesity, hypertension, tiredness#, reduced performance#, weakness#, headache# (#herein referred to as tiredness), dizziness+, nausea+ and vomiting+ (+herein referred to as dizziness) were collected from free-text entries. In addition, data on pain, neurologic, and pulmonary symptoms were analyzed.

For this analysis, we defined stage of puberty as prepubertal in female patients < 8 years of age and in male patients < 9 years of age and pubertal in all other cases, in correspondence with current definitions (23). We re-categorized signs and symptoms of phenotypic endocrine manifestations as follows: In prepubertal girls, the presence of pubic hair (without thelarche), clitoral hypertrophy, hirsutism, deepening of voice, menstrual disorder, acne, greasy hair, sweaty odor, increased muscle strength, accelerated bone age and tall stature was defined as virilization. Pubic hair was classified as “excessive” in pubertal patients (herein defined by age) if reported in the case report form. In prepubertal boys, peripheral precocity was defined in the presence of any of the following features: pubic hair, penile growth, deepening of voice, acne, greasy hair, hirsutism, sweaty odor, increased muscle strength, accelerated bone age, and tall stature. Cushing syndrome was defined in the presence of any of the following features: cushingoid appearance including moon face, buffalo hump and/or striae, hirsutism, acne, mood swing, weight gain/obesity, growth disorder, hypertension, tiredness, and menstrual disorder.

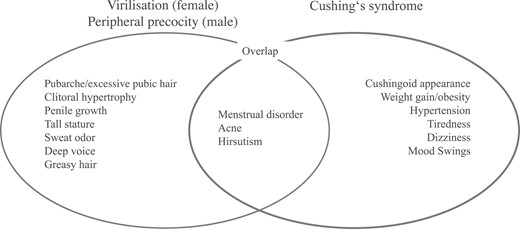

All reported endocrine manifestations were re-reviewed by the authors (Ma.Ku, D.D., and M.K.) and re-classified according to Fig. 1. Patients were classified as mixed phenotype in case signs and symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome were present and in case of overlapping syndromes of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome.

Endocrine signs and symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome and its overlap.

Laboratory findings (plasma and/or urinary steroid hormone profiles) were reviewed to corroborate the endocrine phenotype. The GPOH-MET protocol did not provide central measurement of steroid hormone profiles, but the registry recommended central measurements of plasma (P.M.H.) and urinary steroid hormone profiles (S.A.W.) since 2013. Nevertheless, various methods and approaches were used due to the multicenter design of the study and period in time. For this analysis, we accepted steroid hormone measurements from local laboratories and their interpretation according to local reference ranges.

Statistical Analyses

Differences between groups were determined by the log-rank or chi-squared test or Mann-Whitney- U test and t test as appropriate. A P value of < .05 was considered significant. Differences in the distribution of sexes were calculated in comparison with population-based data using the Genesis database as of December 31, 2019. Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to first event, defined as progression, relapse, or death of disease, whichever occurred first. Survivors were censored at the date of last follow-up. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistical package (version 29.0.0.0).

Results

A total of 155 children and adolescents with ACT [ACA n = 47 (30.3%), ACx n = 19 (12.3%), and ACC n = 89 (57.4%)] were included, with a median age at diagnosis of 4.2 years (range, 0.1-17.8). Sex ratio demonstrated a female preponderance [110 (71.0%) female, 45 (29.0%) male, P = <.001]. Distant metastases were present in 19 of 108 (17.6%) patients with ACC/ACx. Demographic characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

| . | . | Female . | Male . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . |

| Diagnosis | |||||||||

| ACC | 29 | 46.0 | 31 | 66.0 | 22 | 64.7 | 7 | 63.6 | |

| ACA | 24 | 38.1 | 13 | 27.7 | 6 | 17.6 | 4 | 36.4 | |

| ACx | 10 | 15.9 | 3 | 6.4 | 6 | 17.6 | 0 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||||||

| Median | 1.6 | 13.7 | 2.0 | 13.3 | |||||

| Range | 0.1-7.5 | 8.3-17.1 | 0.2-8.2 | 9.0-17.8 | |||||

| Interval of endocrine symptoms prior to diagnosis (months) | |||||||||

| Median | 3.6 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 9.0 | |||||

| Range | 0-61.3 | 0.7-90.6 | 0-29.8 | 0.4-60.0 | |||||

| Endocrine phenotypea | |||||||||

| Virilization | 39 | 61.9 | 17 | 36.2 | 15 | 44.1 | |||

| Cushing | 5 | 7.9 | 8 | 17.0 | 3 | 8.8 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Mixed | 11 | 17.5 | 12 | 25.5 | 6 | 17.6 | 3 | 27.3 | |

| Silent | 8 | 12.7 | 10 | 21.3 | 10 | 29.4 | 6 | 54.5 | |

| Tumor volume (mL) | |||||||||

| Median | 75.0 | 300.7 | 101.3 | 156.0 | |||||

| Range | 0.5-1260.0 | 2.5-2907.0 | 4.0-1254.0 | 9.0-3645.0 | |||||

| Distant metastases in ACC/ACx | |||||||||

| No | 28 | 71.8 | 16 | 47.1 | 19 | 67.9 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| Yes | 1 | 2.6 | 11 | 32.4 | 4 | 14.3 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| No data | 10 | 25.6 | 7 | 20.6 | 5 | 17.9 | 1 | 14.3 | |

| . | . | Female . | Male . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . |

| Diagnosis | |||||||||

| ACC | 29 | 46.0 | 31 | 66.0 | 22 | 64.7 | 7 | 63.6 | |

| ACA | 24 | 38.1 | 13 | 27.7 | 6 | 17.6 | 4 | 36.4 | |

| ACx | 10 | 15.9 | 3 | 6.4 | 6 | 17.6 | 0 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||||||

| Median | 1.6 | 13.7 | 2.0 | 13.3 | |||||

| Range | 0.1-7.5 | 8.3-17.1 | 0.2-8.2 | 9.0-17.8 | |||||

| Interval of endocrine symptoms prior to diagnosis (months) | |||||||||

| Median | 3.6 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 9.0 | |||||

| Range | 0-61.3 | 0.7-90.6 | 0-29.8 | 0.4-60.0 | |||||

| Endocrine phenotypea | |||||||||

| Virilization | 39 | 61.9 | 17 | 36.2 | 15 | 44.1 | |||

| Cushing | 5 | 7.9 | 8 | 17.0 | 3 | 8.8 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Mixed | 11 | 17.5 | 12 | 25.5 | 6 | 17.6 | 3 | 27.3 | |

| Silent | 8 | 12.7 | 10 | 21.3 | 10 | 29.4 | 6 | 54.5 | |

| Tumor volume (mL) | |||||||||

| Median | 75.0 | 300.7 | 101.3 | 156.0 | |||||

| Range | 0.5-1260.0 | 2.5-2907.0 | 4.0-1254.0 | 9.0-3645.0 | |||||

| Distant metastases in ACC/ACx | |||||||||

| No | 28 | 71.8 | 16 | 47.1 | 19 | 67.9 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| Yes | 1 | 2.6 | 11 | 32.4 | 4 | 14.3 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| No data | 10 | 25.6 | 7 | 20.6 | 5 | 17.9 | 1 | 14.3 | |

aGrouping as reported in the case report form.

| . | . | Female . | Male . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . |

| Diagnosis | |||||||||

| ACC | 29 | 46.0 | 31 | 66.0 | 22 | 64.7 | 7 | 63.6 | |

| ACA | 24 | 38.1 | 13 | 27.7 | 6 | 17.6 | 4 | 36.4 | |

| ACx | 10 | 15.9 | 3 | 6.4 | 6 | 17.6 | 0 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||||||

| Median | 1.6 | 13.7 | 2.0 | 13.3 | |||||

| Range | 0.1-7.5 | 8.3-17.1 | 0.2-8.2 | 9.0-17.8 | |||||

| Interval of endocrine symptoms prior to diagnosis (months) | |||||||||

| Median | 3.6 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 9.0 | |||||

| Range | 0-61.3 | 0.7-90.6 | 0-29.8 | 0.4-60.0 | |||||

| Endocrine phenotypea | |||||||||

| Virilization | 39 | 61.9 | 17 | 36.2 | 15 | 44.1 | |||

| Cushing | 5 | 7.9 | 8 | 17.0 | 3 | 8.8 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Mixed | 11 | 17.5 | 12 | 25.5 | 6 | 17.6 | 3 | 27.3 | |

| Silent | 8 | 12.7 | 10 | 21.3 | 10 | 29.4 | 6 | 54.5 | |

| Tumor volume (mL) | |||||||||

| Median | 75.0 | 300.7 | 101.3 | 156.0 | |||||

| Range | 0.5-1260.0 | 2.5-2907.0 | 4.0-1254.0 | 9.0-3645.0 | |||||

| Distant metastases in ACC/ACx | |||||||||

| No | 28 | 71.8 | 16 | 47.1 | 19 | 67.9 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| Yes | 1 | 2.6 | 11 | 32.4 | 4 | 14.3 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| No data | 10 | 25.6 | 7 | 20.6 | 5 | 17.9 | 1 | 14.3 | |

| . | . | Female . | Male . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . |

| Diagnosis | |||||||||

| ACC | 29 | 46.0 | 31 | 66.0 | 22 | 64.7 | 7 | 63.6 | |

| ACA | 24 | 38.1 | 13 | 27.7 | 6 | 17.6 | 4 | 36.4 | |

| ACx | 10 | 15.9 | 3 | 6.4 | 6 | 17.6 | 0 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||||||

| Median | 1.6 | 13.7 | 2.0 | 13.3 | |||||

| Range | 0.1-7.5 | 8.3-17.1 | 0.2-8.2 | 9.0-17.8 | |||||

| Interval of endocrine symptoms prior to diagnosis (months) | |||||||||

| Median | 3.6 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 9.0 | |||||

| Range | 0-61.3 | 0.7-90.6 | 0-29.8 | 0.4-60.0 | |||||

| Endocrine phenotypea | |||||||||

| Virilization | 39 | 61.9 | 17 | 36.2 | 15 | 44.1 | |||

| Cushing | 5 | 7.9 | 8 | 17.0 | 3 | 8.8 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Mixed | 11 | 17.5 | 12 | 25.5 | 6 | 17.6 | 3 | 27.3 | |

| Silent | 8 | 12.7 | 10 | 21.3 | 10 | 29.4 | 6 | 54.5 | |

| Tumor volume (mL) | |||||||||

| Median | 75.0 | 300.7 | 101.3 | 156.0 | |||||

| Range | 0.5-1260.0 | 2.5-2907.0 | 4.0-1254.0 | 9.0-3645.0 | |||||

| Distant metastases in ACC/ACx | |||||||||

| No | 28 | 71.8 | 16 | 47.1 | 19 | 67.9 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| Yes | 1 | 2.6 | 11 | 32.4 | 4 | 14.3 | 3 | 42.9 | |

| No data | 10 | 25.6 | 7 | 20.6 | 5 | 17.9 | 1 | 14.3 | |

aGrouping as reported in the case report form.

A median interval of endocrine symptoms prior to diagnosis of ACT of 4.2 months (range, 0-90.7) was reported. In 70 (of 155; 45.2%) patients, virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) was reported; in 18 (11.6%) patients, Cushing syndrome; and in 33 (21.3%) patients, a mixed phenotype with virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome. The absence of endocrine manifestations was reported in 34 (21.9%) patients.

Phenotypic Endocrine Manifestations of ACT in Prepubertal and Pubertal Female Patients

Of 110 females, 63 (57.2%) patients were prepubertal according to age. The median interval of endocrine symptoms prior to ACT diagnosis in female was 4.2 months (range, 0-90.6). Details on endocrine manifestations are given in Table 2.

Details on the endocrine phenotype and other symptoms of 155 patients with ACT by age and sex

| . | Female . | Male . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | P value . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . | P value . |

| Virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) | ||||||||||

| Pubarche/excessive pubic hair | 43 | 68.3 | 22 | 46.8 | .024 | 19 | 55.9 | 3 | 27.3 | .166 |

| Clitoral hypertrophy | 31 | 49.2 | 6 | 12.8 | <.001 | — | — | — | ||

| Penile growth | — | — | — | 16 | 47.1 | 1 | 9.1 | .024 | ||

| Tall stature | 14 | 22.2 | 4 | 8.5 | .051 | 7 | 20.6 | 1 | 9.1 | .328 |

| Sweat odor | 10 | 15.9 | 7 | 14.9 | .985 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Deep voice | 4 | 6.3 | 12 | 25.5 | .007 | 3 | 8.8 | 0 | 0.0 | .298 |

| Greasy hair | 5 | 7.9 | 2 | 4.3 | .519 | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | .367 |

| Overlapping signs and symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Menstrual disorder (sec. amenorrhea) | 1 | 1.6 | 11 | 23.4 | <.001 | — | — | |||

| Acne | 14 | 22.2 | 17 | 36.2 | .110 | 11 | 32.4 | 1 | 9.1 | .087 |

| Hirsutism | 3 | 4.8 | 9 | 19.1 | .017 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | .565 |

| Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Cushingoid appearance | 3 | 4.8 | 5 | 10.6 | .240 | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 27.3 | .118 |

| Weight gain/obesity | 20 | 31.7 | 16 | 34.0 | .915 | 8 | 23.5 | 5 | 45.5 | .153 |

| Hypertension | 13 | 20.6 | 17 | 36.2 | .075 | 7 | 20.6 | 4 | 36.4 | .372 |

| Tirednessa | 9 | 14.3 | 16 | 34.0 | .022 | 6 | 17.6 | 2 | 18.2 | .924 |

| Dizzinessb | 2 | 3.2 | 8 | 17.0 | .014 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Mood swings | 4 | 6.3 | 1 | 2.1 | .293 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 9.1 | .390 |

| No endocrine signs and symptoms | ||||||||||

| Phenotypic silent | 8 | 12.7 | 8 | 17.0 | .494 | 10 | 29.4 | 4 | 36.4 | .665 |

| Other symptoms | ||||||||||

| Abdominal/back pain | 6 | 9.5 | 12 | 25.5 | .028 | 3 | 8.8 | 6 | 54.5 | .003 |

| . | Female . | Male . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | P value . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . | P value . |

| Virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) | ||||||||||

| Pubarche/excessive pubic hair | 43 | 68.3 | 22 | 46.8 | .024 | 19 | 55.9 | 3 | 27.3 | .166 |

| Clitoral hypertrophy | 31 | 49.2 | 6 | 12.8 | <.001 | — | — | — | ||

| Penile growth | — | — | — | 16 | 47.1 | 1 | 9.1 | .024 | ||

| Tall stature | 14 | 22.2 | 4 | 8.5 | .051 | 7 | 20.6 | 1 | 9.1 | .328 |

| Sweat odor | 10 | 15.9 | 7 | 14.9 | .985 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Deep voice | 4 | 6.3 | 12 | 25.5 | .007 | 3 | 8.8 | 0 | 0.0 | .298 |

| Greasy hair | 5 | 7.9 | 2 | 4.3 | .519 | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | .367 |

| Overlapping signs and symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Menstrual disorder (sec. amenorrhea) | 1 | 1.6 | 11 | 23.4 | <.001 | — | — | |||

| Acne | 14 | 22.2 | 17 | 36.2 | .110 | 11 | 32.4 | 1 | 9.1 | .087 |

| Hirsutism | 3 | 4.8 | 9 | 19.1 | .017 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | .565 |

| Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Cushingoid appearance | 3 | 4.8 | 5 | 10.6 | .240 | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 27.3 | .118 |

| Weight gain/obesity | 20 | 31.7 | 16 | 34.0 | .915 | 8 | 23.5 | 5 | 45.5 | .153 |

| Hypertension | 13 | 20.6 | 17 | 36.2 | .075 | 7 | 20.6 | 4 | 36.4 | .372 |

| Tirednessa | 9 | 14.3 | 16 | 34.0 | .022 | 6 | 17.6 | 2 | 18.2 | .924 |

| Dizzinessb | 2 | 3.2 | 8 | 17.0 | .014 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Mood swings | 4 | 6.3 | 1 | 2.1 | .293 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 9.1 | .390 |

| No endocrine signs and symptoms | ||||||||||

| Phenotypic silent | 8 | 12.7 | 8 | 17.0 | .494 | 10 | 29.4 | 4 | 36.4 | .665 |

| Other symptoms | ||||||||||

| Abdominal/back pain | 6 | 9.5 | 12 | 25.5 | .028 | 3 | 8.8 | 6 | 54.5 | .003 |

aIncluding reduced performance, weakness, and headache.

bIncluding nausea and vomiting.

Details on the endocrine phenotype and other symptoms of 155 patients with ACT by age and sex

| . | Female . | Male . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | P value . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . | P value . |

| Virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) | ||||||||||

| Pubarche/excessive pubic hair | 43 | 68.3 | 22 | 46.8 | .024 | 19 | 55.9 | 3 | 27.3 | .166 |

| Clitoral hypertrophy | 31 | 49.2 | 6 | 12.8 | <.001 | — | — | — | ||

| Penile growth | — | — | — | 16 | 47.1 | 1 | 9.1 | .024 | ||

| Tall stature | 14 | 22.2 | 4 | 8.5 | .051 | 7 | 20.6 | 1 | 9.1 | .328 |

| Sweat odor | 10 | 15.9 | 7 | 14.9 | .985 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Deep voice | 4 | 6.3 | 12 | 25.5 | .007 | 3 | 8.8 | 0 | 0.0 | .298 |

| Greasy hair | 5 | 7.9 | 2 | 4.3 | .519 | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | .367 |

| Overlapping signs and symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Menstrual disorder (sec. amenorrhea) | 1 | 1.6 | 11 | 23.4 | <.001 | — | — | |||

| Acne | 14 | 22.2 | 17 | 36.2 | .110 | 11 | 32.4 | 1 | 9.1 | .087 |

| Hirsutism | 3 | 4.8 | 9 | 19.1 | .017 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | .565 |

| Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Cushingoid appearance | 3 | 4.8 | 5 | 10.6 | .240 | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 27.3 | .118 |

| Weight gain/obesity | 20 | 31.7 | 16 | 34.0 | .915 | 8 | 23.5 | 5 | 45.5 | .153 |

| Hypertension | 13 | 20.6 | 17 | 36.2 | .075 | 7 | 20.6 | 4 | 36.4 | .372 |

| Tirednessa | 9 | 14.3 | 16 | 34.0 | .022 | 6 | 17.6 | 2 | 18.2 | .924 |

| Dizzinessb | 2 | 3.2 | 8 | 17.0 | .014 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Mood swings | 4 | 6.3 | 1 | 2.1 | .293 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 9.1 | .390 |

| No endocrine signs and symptoms | ||||||||||

| Phenotypic silent | 8 | 12.7 | 8 | 17.0 | .494 | 10 | 29.4 | 4 | 36.4 | .665 |

| Other symptoms | ||||||||||

| Abdominal/back pain | 6 | 9.5 | 12 | 25.5 | .028 | 3 | 8.8 | 6 | 54.5 | .003 |

| . | Female . | Male . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | <8 years (n = 63) . | % . | ≥ 8 years (n = 47) . | % . | P value . | <9 years (n = 34) . | % . | ≥ 9 years (n = 11) . | % . | P value . |

| Virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) | ||||||||||

| Pubarche/excessive pubic hair | 43 | 68.3 | 22 | 46.8 | .024 | 19 | 55.9 | 3 | 27.3 | .166 |

| Clitoral hypertrophy | 31 | 49.2 | 6 | 12.8 | <.001 | — | — | — | ||

| Penile growth | — | — | — | 16 | 47.1 | 1 | 9.1 | .024 | ||

| Tall stature | 14 | 22.2 | 4 | 8.5 | .051 | 7 | 20.6 | 1 | 9.1 | .328 |

| Sweat odor | 10 | 15.9 | 7 | 14.9 | .985 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Deep voice | 4 | 6.3 | 12 | 25.5 | .007 | 3 | 8.8 | 0 | 0.0 | .298 |

| Greasy hair | 5 | 7.9 | 2 | 4.3 | .519 | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | .367 |

| Overlapping signs and symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Menstrual disorder (sec. amenorrhea) | 1 | 1.6 | 11 | 23.4 | <.001 | — | — | |||

| Acne | 14 | 22.2 | 17 | 36.2 | .110 | 11 | 32.4 | 1 | 9.1 | .087 |

| Hirsutism | 3 | 4.8 | 9 | 19.1 | .017 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | .565 |

| Cushing syndrome | ||||||||||

| Cushingoid appearance | 3 | 4.8 | 5 | 10.6 | .240 | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 27.3 | .118 |

| Weight gain/obesity | 20 | 31.7 | 16 | 34.0 | .915 | 8 | 23.5 | 5 | 45.5 | .153 |

| Hypertension | 13 | 20.6 | 17 | 36.2 | .075 | 7 | 20.6 | 4 | 36.4 | .372 |

| Tirednessa | 9 | 14.3 | 16 | 34.0 | .022 | 6 | 17.6 | 2 | 18.2 | .924 |

| Dizzinessb | 2 | 3.2 | 8 | 17.0 | .014 | 4 | 11.8 | 1 | 9.1 | .704 |

| Mood swings | 4 | 6.3 | 1 | 2.1 | .293 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 9.1 | .390 |

| No endocrine signs and symptoms | ||||||||||

| Phenotypic silent | 8 | 12.7 | 8 | 17.0 | .494 | 10 | 29.4 | 4 | 36.4 | .665 |

| Other symptoms | ||||||||||

| Abdominal/back pain | 6 | 9.5 | 12 | 25.5 | .028 | 3 | 8.8 | 6 | 54.5 | .003 |

aIncluding reduced performance, weakness, and headache.

bIncluding nausea and vomiting.

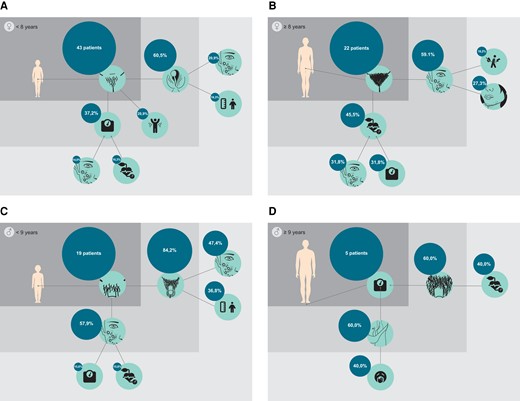

The most frequent endocrine manifestations in 63 prepubertal females are depicted in Fig. 2A. Of 43 patients with pubarche, 26 (60.5%) patients additionally presented with clitoral hypertrophy, 9 (20.9%) patients with clitoral hypertrophy and acne, and 7 (16.3%) patients with clitoral hypertrophy and tall stature. The most frequent symptom combinations are depicted in Fig. 3A. Thelarche was not reported in any prepubertal girl. In 8 (12.7%) of 63 patients, clinical signs and symptoms were reported to be nonexisting.

Frequencies of the most common endocrine signs and symptoms of adrenal hormone excess in ACT in 63 prepubertal females (A), 47 pubertal females (B), 34 prepubertal males (C), 11 pubertal males (D), and in prepubertal (E) and pubertal (F) patients combining female and male patients. Legend:  acne

acne  pubarche

pubarche  clitoral hypertrophy

clitoral hypertrophy  penile growth

penile growth  weight gain

weight gain  hypertension

hypertension  excessive pubic hair

excessive pubic hair  cushingoid appearance

cushingoid appearance  tall stature

tall stature  clitoral hypertrophy/penile growth

clitoral hypertrophy/penile growth  deep voice

deep voice  hirsutism

hirsutism  tiredness

tiredness  abdominal and back pain.

abdominal and back pain.

Most frequent symptom combinations in pre- (A) and pubertal (B) female and pre- (C) and pubertal (D) male. Legend:  pubarche

pubarche  excessive pubic hair

excessive pubic hair  clitoral hypertrophy

clitoral hypertrophy  acne

acne  sweat odor

sweat odor  hypertension

hypertension  weight gain

weight gain  tall stature

tall stature  menstrual disorder

menstrual disorder  hirsutism

hirsutism  pubarche

pubarche  excessive pubic hair

excessive pubic hair  penile growth

penile growth  cushingoid appearance

cushingoid appearance  tiredness.

tiredness.

The most frequently reported endocrine signs and symptoms in 47 pubertal females are illustrated in Fig. 2B. Of 22 patients with excessive pubic hair, 13 (59.1%) additionally presented with acne, 6 (27.3%) with acne and hirsutism, and 4 (18.2%) with acne and menstrual disorders (Fig. 3B). In 8 (17.0%) of 47 patients, the absence of any endocrine manifestation was reported. In addition, 12 (25.5%) pubertal females presented with abdominal/back pain.

Clitoral hypertrophy (P < .001) and pubarche (P = .024) were more frequently present in prepubertal compared to pubertal female. Deep voice (P = .007), menstrual disorders (P < .001), dizziness (P = .014), tiredness (P = .022), and abdominal/back pain (P = .028) were more frequent in pubertal compared to prepubertal female.

No differences were observed in body mass index in prepubertal and pubertal patients compared to age-adjusted data from the KiGGS study (24).

Of 110 female patients, 2 prepubertal and 2 pubertal patients presented with neurologic symptoms, including posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, focal neurologic signs, and seizures (due to hyponatremia in 1 patient). Four pubertal patients presented with respiratory symptoms due to pulmonary metastases and pulmonary and cardiogenic embolism.

Phenotypic Endocrine Manifestations of ACT in Prepubertal and Pubertal Male Patients

Of 45 males, 34 (75.5%) patients were prepubertal according to age. The median interval from first endocrine signs and symptoms to ACT diagnosis was 3.9 months (range, 0-60.0).

Leading endocrine signs and symptoms of adrenal hormone excess in 34 prepubertal males are illustrated in Fig. 2C. Of 19 patients with pubarche, 16 (84.2%) additionally presented with penile growth, 9 (47.4%) with penile growth and acne, and 4 (21.1%) with penile growth and weight gain/obesity (Fig. 3C).

The leading endocrine symptoms in 11 pubertal male patients are depicted in Fig. 2D. Of 5 patients with weight gain/obesity, 3 (60.0%) additionally presented with cushingoid appearance, and 2 (40.0%) with cushingoid appearance and tiredness (Fig. 3D). In 4 (36.4%) of 11 pubertal male patients, the absence of any endocrine manifestation was reported. In addition, abdominal/back pain was reported in 54.5% of patients, thereby being the most frequent symptom in pubertal male.

Penile growth was more frequent in prepubertal compared to pubertal male (P = .024), whereas pain was more frequently reported in pubertal compared to prepubertal patients (P = .003).

Clinical Manifestations in Prepubertal Compared to Pubertal Patients

Genital changes, including clitoral hypertrophy and penile growth (P < .001), pubarche (P = .024), and tall stature (P = .031) were more frequently reported in prepubertal patients compared to pubertal patients. Deep voice (P = .016), hirsutism (P = .012), hypertension (P = .042), abdominal/back pain (P < .001), and tiredness (P = .037) were more frequent in pubertal compared to pubertal patients (Fig. 2E and 2F). No difference was observed for cushingoid appearance (P = .110). The interval from onset of first symptoms to ACT diagnosis was shorter in prepubertal compared to pubertal patients (P = .015).

Phenotypic Endocrine Manifestations and Laboratory Findings

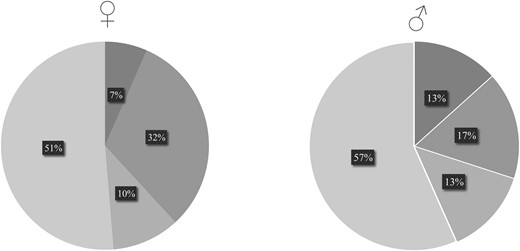

Next, we looked in more detail at those 106 of 155 (68.4%) patients for whom data on laboratory findings of androgens und glucocorticoids were available. To this end, we first re-classified endocrine signs and symptoms as virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male), Cushing syndrome, mixed phenotype, and silent endocrine phenotype as described in the “Methods” section (Fig. 4).

Frequencies of endocrine phenotypes following re-classification of all reported endocrine signs and symptoms in prepubertal and pubertal female and male patients. Legend:  silent

silent  virilization/peripheral precocity

virilization/peripheral precocity  Cushing syndrome

Cushing syndrome  mixed.

mixed.

Clinical diagnosis of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) was confirmed by laboratory findings in 62 (of 63; 98.4%) girls and 22 (of 22; 100%) boys, whereas clinical diagnosis was not confirmed by laboratory findings in 1 (1.6%) girl. The median number of symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) was 3 [1-7].

Laboratory findings confirmed clinical diagnosis of Cushing syndrome in 69 (of 71; 97.2%) patients. In those patients, the median number of symptoms of the Cushing syndrome complex was 2 [1-5]. In another 24 patients without any sign or symptom of Cushing syndrome, laboratory findings demonstrated elevated cortisol levels.

Of 9 patients with clinical silent endocrine phenotypes, 3 (of 5; 60.0%) female and 3 (of 4; 75.0%) male were identified with elevated androgen levels. In 2 (of 5; 40.0%) female patients and 1 (of 4; 25%) male patient, the absence of any sign or symptom of the Cushing syndrome complex was corroborated by normal cortisol levels.

In 55 patients with a mixed endocrine phenotype on the basis of laboratory findings, overlapping symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) and Cushing syndrome were present in 41 (77.4%) patients. In those patients, the median number of presenting symptoms was 5 [1-10].

In addition, laboratory findings identified hyperaldosteronism in 4 females with hypertension and elevated estrogen levels in one pubertal male with gynecomastia and “feminization.”

Endocrine Phenotype and Tumor Features

We further looked at endocrine manifestations and tumor features in more detail. The most frequent symptoms in patients of prepubertal age with ACA were pubarche (17; 56.7%), weight gain/obesity (12; 40.0%), and clitoral hypertrophy/penile growth (10; 33.3%), whereas pubarche (37; 72.5%), clitoral hypertrophy/penile growth (29; 56.9%), and acne (16; 31.4%) were most frequent in patients with ACC. In pubertal patients with ACA, the most frequent symptoms were excessive pubic hair (8; 47.1%), weight gain/obesity (5; 29.4%), and sweat odor or deep voice (4 each; 23.6%), while in patients with ACC, the most frequent symptoms were hypertension (19; 50.0%), excessive pubic hair (16; 42.1%), and weight gain/obesity and tiredness (15 each; 39.5%). Penile growth (P = .008) and acne (P = .028) were more frequently reported in patients with ACC compared to ACA. We also observed a trend toward more frequent genital changes (clitoral hypertrophy in female and penile growth in male combined) (P = .066) and tiredness (P = .084) in patients with ACC compared to patients with ACA. No differences were observed for other endocrine manifestations, including cushingoid appearance.

We next compared endocrine manifestations in 89 ACC patients with and without metastases at initial diagnosis. Clitoral hypertrophy (P = .015) was more frequently reported in patients without metastatic disease, while hypertension (P = .003) was more frequently observed in patients with metastases. No differences were observed for other endocrine manifestations. In addition, no differences were observed for endocrine manifestations in ACC patients with Ki67-index < 15% compared to Ki67-index ≥ 15%.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive analysis of the various endocrine manifestations in 155 children and adolescents with ACT. The latency from first endocrine symptoms to ACT diagnosis was 4.8 months (range, 0-90.7), in line with previous reports (3.0-8.1 months) (14, 15). Our data demonstrate that the endocrine phenotype is age- and sex-dependent. It is not associated with tumor dignity. The most frequent overarching endocrine phenotype is mixed (virilization/peripheral precocity combined with Cushing syndrome; 53.8%), followed by virilization/peripheral precocity (27.9%), and Cushing syndrome (11.5%), which has previously been reported (11, 20, 25).

In patients of prepubertal age, endocrine manifestations were predominantly shaped by the effects of androgen hormone excess causing signs and symptoms of virilization/contrasexual peripheral precocity in females and isosexual precocity (eg, pubarche, penile growth) in males. The absence of premature thelarche supported the isolated activation of the adrenals, with the consequent manifestations of excessive androgens and/corticosteroids production, but not of the ovaries. In addition, some patients of prepubertal age presented with signs and symptoms of Cushing syndrome (eg, weight gain, acne, hypertension) caused by hypercortisolism. However, clinical diagnosis of Cushing syndrome was challenging in some cases for 3 reasons: (i) various definitions of Cushing syndrome are used in the literature (16, 26); (ii) there is an overlap of signs and symptoms of Cushing syndrome and virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) (Fig. 1); and (iii) endocrine manifestations consistent with Cushing syndrome were frequently “unspecific” such as hypertension, acne, and weight gain, whereas “typical” symptoms of Cushing syndrome, such as moon face and buffalo hump, were less frequently reported. It should not go unmentioned that hypertension may be caused by vascular compression due to local tumor growth. However, only 2 of 41 hypertensive patients in our cohort presented with isolated hypertension.

On the other hand, in patients of pubertal age, the clinical effects of androgen hormone excess were less striking, shaping a different, less distinctive endocrine phenotype of virilization or puberty, including acne and excessive pubic hair in both sexes. Notably, these symptoms again overlap with clinical Cushing features. Cushing syndrome was more frequently diagnosed in pubertal patients and, thus, may be clinically more apparent.

Despite common usage in oncologic reports, our data clearly demonstrate that virilization is too unspecific to characterize the various effects of adrenal hormone excess in pediatric patients with ACT. In fact, excessive pubic hair was the leading manifestation in both sexes and all ages. Clitoral hypertrophy was only affecting prepubertal females. Male and pubertal female rather presented with symptoms of the Cushing syndrome complex.

Intimate knowledge of the multi-faceted endocrine phenotypes in children and adolescents with ACT is of particular importance for early diagnosis. We demonstrated that in pediatric patients with ACT, excessive pubic hair was the most frequent symptom (73 of 155 patients), including 4 patients with this as the only symptom. According to recent guidelines, isolated premature pubarche only implies follow-up within 3 months (27). From our point of view, this needs to be discussed. An ultrasound examination and urinary steroid hormone profile are simple, affordable, and without side effects but facilitate identification of pediatric patients with ACT as early as possible. Noteably, in 80.3% of patients of prepubertal age at least 2 symptoms of (precocious) androgenization were present. However, it should not go unmentioned that data on bone age and growth rate were not available, representing the most important limitation of our study. In endocrinologic recommendations for diagnostic workup in pediatric patients with signs and symptoms of peripheral precocity and other conditions associated with adrenal hypersecretion (28), these are important parameters with implications for further management. Adrenal hypersecretion can often lead to precocious closure of growth plates in long bones and, therefore, change the growth curve, and finally, determine short stature, among other side effects. Some of the multiple signs and symptoms of Cushing syndrome (eg, hypertension, weight gain, acne) were frequently present, particularly in pubertal patients. However, Cushing syndrome was undiagnosed in a number of patients in our study, most likely in patients of prepubertal age with signs and symptoms of virilization (female)/peripheral precocity (male) which overlap with Cushing syndrome. In some cases, indeed, Cushing syndrome was clinically overlooked or only substantiated by the detection of excessive cortisol levels. In line with this, the phenotypic endocrine manifestations did not entirely reflect the tumor's hormonal secretory profile in some cases. Nonetheless, increased attention to Cushing syndrome in the context of ACT is important for predicting prognosis and risk stratification (12).

Our data demonstrate that the endocrine phenotype does not predict tumor dignity. However, we observed a trend to more severe endocrine symptoms in patients with ACC. We previously reported that the tumor volume of pediatric patients with ACC compared to patients with ACA is significantly increased (29). Supported by our data we hypothesize that the endocrine phenotype is predominantly shaped by the adrenal hormone excess caused by hormone producing tumor cells rather than tumor dignity.

Our analysis has several limitations including its retrospective character, data availability, and various methods used for laboratory testing:

Data on stage and pace of pubertal development including bone age, growth rate, and testicular volume were not available.

Analysis of the evolution of endocrine manifestations over time including severity was not possible.

Laboratory results were only categorically reported, details on methods and pre-test circumstances were not available. Specifically, detailed data on cortisol at midnight saliva, 8 Am blood or 24-hour urinary collection and/or altered suppression tests and type were not available. However, this information is important as the approach and cutoffs of Cushing diagnosis, especially in younger children, is still debated.

Important limitations in frequency assessment due to data availability.

Nevertheless, our data highlight the various endocrine phenotypes in children and adolescents with ACT and raise awareness to the multi-faceted signs and symptoms of this very rare pediatric malignancy.

Conclusion

The endocrine phenotype in children and adolescents with ACT is age- and sex-dependent but not associated with tumor dignity. In prepubertal patients the phenotype is predominantly shaped by signs and symptoms of androgen hormone excess. In pubertal patients this is less obvious while abdominal/back pain and symptoms of Cushing syndrome are more apparent.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this work were presented as a poster presentation at the JA-PED 2023, Ulm, Germany, November 2–4, 2023. The engaging infographics and illustrations were created and graphically designed by Kolja Kunstreich.

Funding

The German MET studies were funded by Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung, grant number DKS 2014.06, DKS 2017.16, DKS 2021.11, W.A. Drenckmann Stiftung, Mitteldeutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung, and Magdeburger Förderkreis krebskranker Kinder e.V. A.H. was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Germwithin the CRC/Transregio 205/2 (314061271-TRR-205).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions.

References

Abbreviations

- ACA

adrenocortical adenoma

- ACC

adrenocortical carcinoma

- ACT

adrenocortical tumor

- ACx

adrenocortical tumor of undetermined malignant potential

- GPOH-MET

German Paediatric Oncology Haematology-Malignant Endocrine Tumour

Author notes

Antje Redlich and Michaela Kuhlen contributed equally.