-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Helen Gnanapragasam, Naghma Mustafa, Mary Bierbrauer, Tara Andrea Providence, Paresh Dandona, Semaglutide in Cystic Fibrosis-Related Diabetes, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 7, July 2020, Pages 2341–2344, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa167

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In spite of the evidence that inadequately controlled glycemia is associated with worse clinical outcomes, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) is not well controlled in a majority of patients. The objective of this report is to demonstrate the effect of the addition of semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA), to basal insulin to control glycemia in one such patient.

The replacement of rapidly acting prandial insulin with semaglutide weekly with continuation of basal insulin. Glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) was conducted.

There was a significant improvement in glycemic control, reduction in HbA1c from 9.1% to 6.7% and stable euglycemic pattern on CGM (mean glucose, 142 mg/dL; SD, 51) within 3 months of starting treatment. There was no increase in plasma pancreatic enzyme concentrations.

Semaglutide at a low dose was able to replace prandial insulin and control glycemia in combination with basal insulin.

Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) affects 40% to 50% of adults with cystic fibrosis (1). Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment of CFRD is associated with a slower rate of pulmonary decline and is important for increasing lifespan (2, 3). CFRD is characterized by postprandial hyperglycemia (4). Gastric emptying and the release of the incretin hormones are central to postprandial glycemia. Studies have shown that CFRD patients have delayed release of insulin in response to glucose load and experience higher mean glucose value when receiving a glucose challenge (5). We report a case to demonstrate the potential importance of including glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) therapy to the standard of care of this condition with the combination of long- and short-acting insulin therapy.

Case Description

A 21-year-old man with cystic fibrosis (CF), on treatment with pancreatic enzymes (Creon), underwent a routine screening for CFRD. An oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was consistent with CFRD, with an impaired fasting blood glucose of 118 mg/dL and a 2-hour glucose of 236 mg/dL with a glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of 5.6%. Low-dose insulin therapy was recommended, but he did not start due to his ongoing influenza. Sixteen months later, his HbA1c was found to be 10.4%; he was initiated on glargine 15 Units. Subsequently, insulin lispro (Humalog) was added for breakfast (2U), lunch (2U) and dinner (3U). His HbA1c was 9.1% at his initial visit to our Diabetes Endocrinology Center 10 months later, with reports of multiple hypoglycemic episodes. Baseline C-peptide of 0.64 ng/mL (normal range, 0.8-3.85), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) < 5 IU/mL, lipase < 5 U/L (7-80 U/L) and amylase of 28 U/L (21-101 U/L) were recorded.

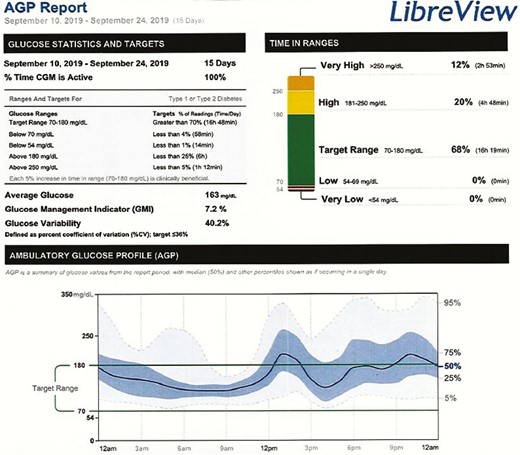

Semaglutide 0.13 mg weekly (8 clicks) was added in addition to glargine 15 Units. Four weeks later, there was a significant improvement in glycemia (Fig. 1). His CGM showed time in range (70-180mg/dL) 68%; above range (> 180mg/dL) 32%; and below range (70 mg/dL) 0%, with average glucose of 163 mg/dL and standard deviation (SD) of 65.6 mg/dL Preprandial humalog was stopped and he was switched to small correctional doses only to treat hyperglycemia after high carbohydrate meals.

CGM for 2 weeks after initiation of semaglutide. Note the improvement in glycemia and the absence of hypoglycemia.

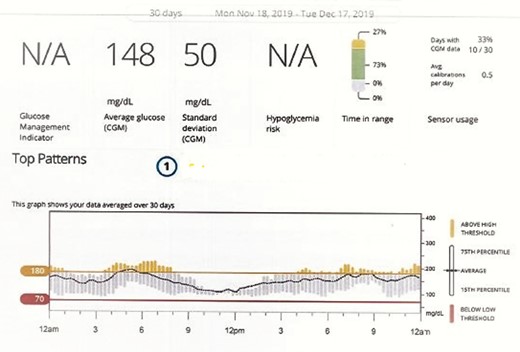

The patient was placed on continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). His HbA1c improved to 6.8% over the span of 3 months with no changes in pancreatic enzymes (lipase < 5 and amylase 33). Interestingly, he reported not using any correctional prandial insulin during this period. Semaglutide was then up-titrated to 0.16 mcg weekly (10 clicks) with no changes observed in pancreatic enzymes on monthly surveillance. Humalog was stopped altogether. Additionally, with the up-titration of semaglutide, CGM showed an even more significant improvement in time in range at 77% with 23% above range, with a mean glucose of 142 mg/dL and SD of 51 mg/dL (Fig. 2). His best day during this 30-day period showed blood glucose in the target range 92% of the time, and his HbA1c was 6.7%. There was no hypoglycemic event recorded on CGM.

CGM after initiation of semaglutide after 12 weeks. Note the absence of hypoglycemia; mean glucose was 148 mg/dL and HbA1c was 6.7%. There was a further reduction in glycemic oscillations.

A recent posttreatment C-peptide concentration obtained 5 months after the institution of semaglutide was 0.77 ng/mL. During the entire period of semaglutide administration, the patient did not experience nausea, upper abdominal pain/discomfort, or diarrhea. He lost 2 kg (from 77 to 75 kg) in body weight over 6 months of treatment with semaglutide.

Discussion

It is clear that the administration of a small dose of semaglutide in combination with basal insulin led to a marked and rapid improvement in glycemic control of this patient with CFRD who had residual β-cell function as reflected in measurable C-peptide concentration. His HbA1c level fell from 9.1% to 6.7% in 3 months. In CF patients, significant C-peptide concentrations are measurable, even with little or no exocrine function (6). This potential can be harnessed through GLP-1RA therapy which stimulates endogenous insulin secretion and suppresses glucagon secretion while suppressing appetite and slowing gastric emptying. Consistent with the concept of GLP-1–induced insulin secretion, there was an increase in plasma concentration of C-peptide from 0.64 ng/mL to 0.77 ng/mL in the fasting state. As mentioned above, there was no nausea or other gastrointestinal symptoms. Serial pancreatic enzyme measurements also did not alter. However, there was a weight loss of 2 kg over the treatment period, despite the recommended high protein and carbohydrate diet.

Previous studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between change in gastric emptying and changes in peak postprandial blood glucose levels in CF patients and a sluggish postprandial insulin response (4). While other studies have demonstrated the late compensatory hyperinsulinemia causing postprandial hypoglycemia after a meal challenge (7), it is relevant that the concentrations of 2 major incretins, gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) (8) and GLP-1 (9) are significantly diminished in patients with CFRD. GLP-1RA therapy could potentially address these issues. Since a significant proportion of patients experience nausea and other gastrointestinal symptoms following GLP-1 receptor agents, we were extremely cautious in starting semaglutide, the most potent GLP-1 receptor agonist available, using only half of the minimal dose. Other advantages of GLP-1RA include their suppression of inflammation (10) and reduction of glycemic oscillations, even in type 1 diabetics (11).

There is one previous report (12) on the effects of treating CFRD patients having impaired glucose tolerance with exenatide. A single dose of 2.5 mcg of this drug reduced the glycemic excursion and the area under the curve for glucose significantly, following a meal challenge in 6 participants on 2 days in a double-blinded randomized crossover trial. Thus, this drug has the potential of preventing the progression of prediabetes to diabetes in patients with CFRD. This study also demonstrated slowing of gastric emptying by exenatide in these patients. Although there was no significant difference in the baseline measure of fasting glucose, C-peptide, glucagon, GLP-1, or GIP, exenatide use was noted to suppress the concentrations of endogenous postprandial insulin, C-peptide, GLP-1, and GIP, due to profound slowing of gastric emptying without any changes in glucagon secretion. It would be useful to investigate these mediators in future studies.

The issue of weight loss with GLP-1RA is important in the context of CF, since these patients are usually underweight due to malabsorption and recurrent infections. This is the reason why we used only half of the minimal dose of semaglutide. In spite of this, our patient lost 2 Kg over the treatment period. However, with the improved glycemic control and the absence/reduction of infections, the overall metabolic status and clinical outcomes may improve. In addition, our recent work has shown that with liraglutide, a GLP-1RA, the induced weight loss is largely confined to adipose tissue with preservation of the lean body mass (13).

We conclude that GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy can be used with basal insulin in patients with residual C-peptide safely, thereby reducing both postprandial hyperglycemia and hypoglycemic events without predisposing to pancreatitis. A recent meta-analysis of GLP-1RA therapy demonstrates that there is no risk of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer following the use of these drugs in diabetic patients (14). More studies are required to establish GLP-1RA therapy for the treatment of CFRD.

Abbreviations

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFRD

cystic fibrosis-related diabetes

- CGM

continuous glucose monitoring

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1

- GLP-1RA

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Zahid Sayeed for his assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: There are no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

Author notes

These authors contributed equally to the manuscript.