-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Esther Van Parys, Duc Tran, Imca Sampers, Thierry Benezech, Pieter-Jan Loveniers, Frank Devlieghere, Hans De Steur, Xavier Gellynck, Joachim J Schouteten, Evaluating collaborative scenarios for short food supply chains: a case study on high-level processing technology, International Journal of Food Science and Technology, Volume 58, Issue 10, October 2023, Pages 5591–5601, https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.16551

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study examined three collaborative scenarios for the implementation of a high-level aseptic filling machine in small-scale food processing for improved food safety in short food supply chains. A two-stage research design was implemented, based on an exploration and evaluation phase. Two workshops were organised to conceptualise the following scenarios: mobile packaging, cooperative and individual ownership. A novel approach to the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats-analytical hierarchy process methodology was used to compare stakeholder perceptions and preferences for different scenarios within one case study. Financial benefits played a key role in each collaborative scenario. The most suitable scenario was found to be the mobile packaging, offering flexibility and no initial investment cost while enabling collaborations. The cooperative scenario has the potential for centralised logistics and marketing while being conscious of its organisational structure. Individual ownership should also focus on centralised logistics and marketing while considering food safety and flexibility limitations.

Introduction

The concept of short food supply chains (SFSC), originally defined by Marsden et al. (2000), emerged from the movement to establish closer relationships between producers and consumers (Marsden et al., 2000; Renkema & Hilletofth, 2022). The scale and location of production can influence consumers' judgement, supporting the increasing demand for foods from shorter chains, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic (Profeta & Hamm, 2019; Etale & Siegrist, 2021). However, SFSC that focus on direct marketing may not be able to meet high volumes and can be labour-intensive (Marsden et al., 2000; Clark & Inwood, 2016). Some studies suggest that the on-farm businesses, e.g. interacting face to face with their consumers, in SFSC may reach saturation and advocate for a more collaborative approach to create added value in local food systems by going beyond direct marketing (Ilbery & Maye, 2005; Clark & Inwood, 2016; Tiganis et al., 2023).

Scaling-up SFSC beyond direct marketing can create more efficient value chains while bridging the gap between producers and consumers to strengthen socio-economic sustainability (Marsden et al., 2000; Renkema & Hilletofth, 2022). This type of proximate engagement with consumers can serve as a countermovement to conventional distribution systems (Wubben et al., 2013; Clark & Inwood, 2016). However, expanding the reach of SFSC also poses challenges as they often operate outside of the global supply chain and its cost-effective environment (Aggestam et al., 2017). Clark & Inwood (2016) viewed cooperation as a scaling-up strategy for alternative vertical integration in SFSC. Both conventional food supply chains and SFSC have faced environmental challenges, leading to the need for redesigning these chains and the emergence of hybrid concepts beyond the dichotomy of these two extremes (Ilbery & Maye, 2005; Thome et al., 2021).

Collaboration in the agri-food chain can bring about several benefits, including reduced time spent searching for suppliers, decreased risk of supply disruptions, improved knowledge sharing, enhanced market access and product availability and optimisation of sustainability performance (Matopoulos et al., 2007; León-Bravo et al., 2017). However, the agri-food chain is known to be a challenging environment for collaboration, characterised by high levels of complexity and specific product-related requirements which can limit the range of possible collaborators (Matopoulos et al., 2007; Badraoui et al., 2020). The pressure to achieve economic success often leaves little time to develop management strategies and social networks (Darnhofer, 2010; Contzen & Häberli, 2021). Technological innovations, such as processing equipment, can serve as a starting point for establishing a constructive environment for collaboration in which shared marketing opportunities can be developed (Bianchi, 2010; Darnhofer, 2010).

Small-scale food processing faces several challenges, such as lack of infrastructure, transportation and energy costs and difficulty keeping up with production and marketing demand (Clark & Inwood, 2016; Lutz et al., 2017). Collaboration can serve as a tool to make processing equipment more accessible, create strategic partnerships for shared infrastructure, reduce costs and working time and provide opportunities for knowledge transfer (Matson & Thayer, 2013; Lutz et al., 2017). The EU hygiene rules were identified as a hurdle for small and medium-sized producers to collaborate and scale-up SFSC, according to the European Commission's report on Innovative SFSC. However, implementing high-level small-scale processing equipment can address challenges related to the availability and expectations of food processing, thereby improving food safety and competitiveness (Bramsiepe et al., 2012; Buckley, 2015; EIP-Agri, 2015). An aseptic filling machine for packaging liquid and semi-liquid products could address the need for adapted processing equipment for small processors and is therefore used as a case study in this paper.

The study aims to analyse stakeholders' perceptions and preferences towards processing equipment adapted to small-scale processing, which is a relatively underdeveloped research area. A combination of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis and the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) is used to evaluate possible collaborative scenarios to scale-up SFSC. In literature, SWOT-AHP has been applied within agri-food chains in a variety of contexts such as regional sustainable development (Ali et al., 2021; Kaymaz et al., 2022), policy implementations (Henríquez-Antipa & Cárcamo, 2019), nutrition security (Olum et al., 2018) and forest management (Stainback et al., 2012; Miner et al., 2021). The application of SWOT-AHP to compare different scenarios within one case study is, as far as the authors know, absent in current the literature.

Methodology

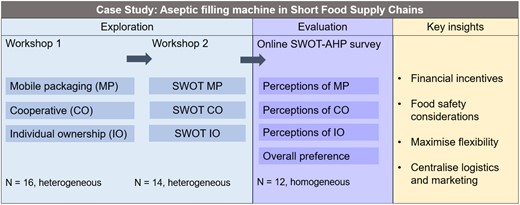

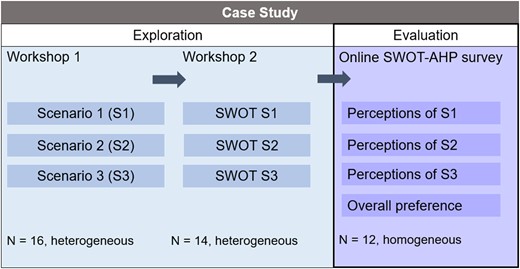

The research was carried out in an exploration phase and an evaluation phase, an overview of the research design is shown in Fig. 1. The exploration phase contained two stakeholder workshops to conceptualise implementation scenarios according to the case study. Each stakeholder workshop included three elements: a general introduction of the case study, discussion sessions in smaller groups and a final discussion with all the stakeholders present. The workshops took place in an online format, due to the COVID-19 measures at the time of data collection.

Three collaborative scenarios for the exploitation of the case study were defined in the first workshop. Technological, environmental and socio-economic aspects were discussed by a heterogeneous group of sixteen stakeholders representing the different actors in the food chain. The stakeholders were selected through convenience and judgement sampling to be relevant for the case study. They were a mix of three small and two large processors, four agricultural representatives, three researchers, one technical advisor, one local politician, one distributor and one retail representative. Table 1 synthesises the three collaborative scenarios based on the stakeholder inputs to increase accessibility for high-level processing equipment for small processors. The second workshop was organised to identify the SWOT. Invitations were extended to relevant stakeholders from the first workshop, together with additional small processors. The fourteen stakeholders present, were a mix of six small processors, three agricultural representatives, two technical experts, one distributor, one researcher and one financial advisor.

| Scenario . | Summary . |

|---|---|

| Mobile packaging | A service company provides a mobile packaging machine accompanied by a fixed operator. Water and waste management needs to be handled by the producer on site. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the service company, which can be labelled by the client. |

| Cooperative | The packaging machine functions within a cooperative. Investment costs are shared by the members. The cooperative can assign a fixed operator for efficiency and maintenance. Opportunities are present to produce under a common brand and instal shared logistics and distribution. |

| Individual ownership | The packaging machine is owned by one company in a fixed location. External producers can use the machine on available timeslots. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the owner, which can be labelled by the client. Opportunities are present to provide logistics and distribution services. |

| Scenario . | Summary . |

|---|---|

| Mobile packaging | A service company provides a mobile packaging machine accompanied by a fixed operator. Water and waste management needs to be handled by the producer on site. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the service company, which can be labelled by the client. |

| Cooperative | The packaging machine functions within a cooperative. Investment costs are shared by the members. The cooperative can assign a fixed operator for efficiency and maintenance. Opportunities are present to produce under a common brand and instal shared logistics and distribution. |

| Individual ownership | The packaging machine is owned by one company in a fixed location. External producers can use the machine on available timeslots. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the owner, which can be labelled by the client. Opportunities are present to provide logistics and distribution services. |

| Scenario . | Summary . |

|---|---|

| Mobile packaging | A service company provides a mobile packaging machine accompanied by a fixed operator. Water and waste management needs to be handled by the producer on site. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the service company, which can be labelled by the client. |

| Cooperative | The packaging machine functions within a cooperative. Investment costs are shared by the members. The cooperative can assign a fixed operator for efficiency and maintenance. Opportunities are present to produce under a common brand and instal shared logistics and distribution. |

| Individual ownership | The packaging machine is owned by one company in a fixed location. External producers can use the machine on available timeslots. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the owner, which can be labelled by the client. Opportunities are present to provide logistics and distribution services. |

| Scenario . | Summary . |

|---|---|

| Mobile packaging | A service company provides a mobile packaging machine accompanied by a fixed operator. Water and waste management needs to be handled by the producer on site. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the service company, which can be labelled by the client. |

| Cooperative | The packaging machine functions within a cooperative. Investment costs are shared by the members. The cooperative can assign a fixed operator for efficiency and maintenance. Opportunities are present to produce under a common brand and instal shared logistics and distribution. |

| Individual ownership | The packaging machine is owned by one company in a fixed location. External producers can use the machine on available timeslots. Neutral packaging materials are provided by the owner, which can be labelled by the client. Opportunities are present to provide logistics and distribution services. |

The evaluation was performed with an online survey using Microsoft Excel 2019 to assign quantitative values to the individual SWOT factors and categories of each scenario. Respondents received randomised versions of the survey presenting a different order of the scenarios. The sample for the survey consisted of small processors of liquid food products active in Belgian SFSC. Respondents were identified with judgement sampling based on their affiliation with SFSC and were screened to make sure they had the correct processing activities through telephone conversations. One respondent from the survey also participated in the initial workshops.

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats is a convenient tool for strategic analysis which maps the internal (strengths, weaknesses) and external (opportunities, threats) aspects. The analytical capacity is limited as it is a qualitative method and the importance of the generated factors is lacking (Kurttila et al., 2000; Oreski, 2012). A follow-up survey was designed to assign quantitative values to the individual SWOT factors and categories. The survey used the AHP method, originally designed by Saaty (1977). AHP allows decision-makers to systematically assign relative priorities through pairwise comparison (Kurttila et al., 2000; Oreski, 2012). SWOT-AHP does not require large sample sizes, such as in classical statistical analyses, but can be fulfilled with small samples when they have sufficient knowledge of the subject (Kurttila et al., 2000).

The hybrid SWOT-AHP method is based on two levels of pairwise comparisons, between the factors within each category (SWOT) and the categories themselves. These comparisons are made to calculate local priority scores, scaling factors and global priority scores according to the eigenvalue method (Kurttila et al., 2000; Stainback et al., 2012). All pairwise comparisons were scaled from one to nine according to Saaty (1977). Reciprocal matrices were computed for pairwise comparisons to measure the priorities. The relative importance of each factor, category and scenario was calculated with normalised matrices. The average of each row in the normalised matrix results in the local priority scores. The global priority scores were generated by multiplying the local priority scores with the corresponding scaling factors of the SWOT categories. This study is unique because it applies SWOT-AHP on different scenarios within one case study, which allows the introduction of a third level of comparison. While the proportion of the positive and negative scaling factors indicates the perception of each scenario, the design of the study lends itself to also generating a scenario priority score for the overall preference of the scenarios.

Human judgements can result in inconsistencies when making pairwise comparisons. The consistency ratio (CR) reflects the level of consistency within the matrix. The CR compares the consistency index (CI = (λmax − n)/(n – 1)), based on the largest eigenvalue λmax and the random index (RI) created from a random matrix of order n. The CR is defined as CR = CI/RI. For pairwise comparisons to be consistent, the CR cannot be higher than the threshold of 0.1 (Saaty, 1977; Miner et al., 2021). The average CR of the pairwise comparisons in this study always complied with the threshold.

Results

The survey was completed by twelve small processors of liquid food products. Four respondents had processing activities in the fruits and vegetables sector, eight respondents in the dairy sector and one of the respondents was active in both. One respondent does not operate in agricultural production, but is a social enterprise specialised in packaging food products for regional producers. Out of twelve respondents, eleven respondents were directly active in the SFSC with an average share of 56%. In the next paragraphs, the global priority scores and scaling factors within each scenario are discussed. The SWOT factors of the scenarios are referred to as mS/W/O/T (mobile packaging), cS/W/O/T (cooperative) and iS/W/O/T (individual ownership). An overview of each SWOT per scenario and the local and global priority scores are given in the Annex.

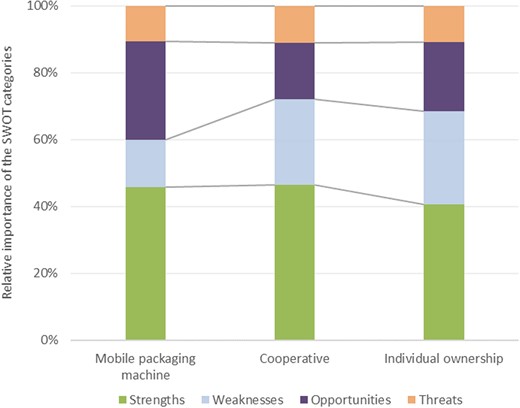

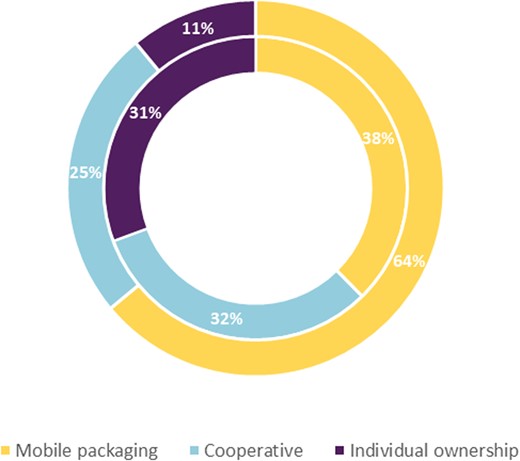

The proportions of the scaling factors, for example, the relative importance of each SWOT category, according to the three scenarios are shown in Fig. 2. The relative importance of the scaling factors of the different scenarios gives insights into how small processors perceive the scenarios within the case study. The mobile packaging scenario scores highest for the positive categories (strengths, opportunities) and lowest for the negative categories (weaknesses, threats), meaning this scenario will be more easily accepted by small processors for implementation. The cooperative scenario ranks second, followed by individual ownership although the differences between the two scenarios are minimal.

The relative importance of SWOT categories, per collaborative scenario.

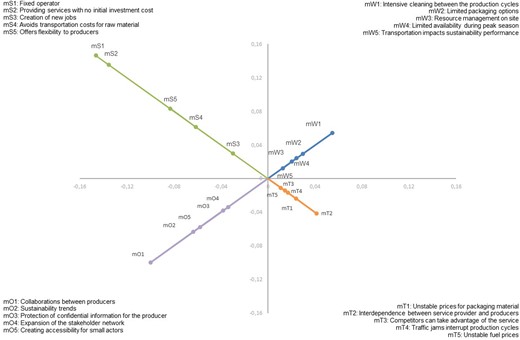

The distribution of global priority scores for the mobile packaging scenario is illustrated in Fig. 3. The factors with the highest global priority scores were related to the presence of a fixed operator (mS1, 0.146) and the absence of initial investment costs for small processors using the service (mS2, 0.135). The packaging service is offered with a fixed operator and no initial investment costs for small processors using the service. The opportunity focusing on collaborations between producers has the highest global priority score within the category (mO1,0.100). The mobile packaging scenario offers these advantages while creating flexibility for its users without commitment to fixed infrastructure (mS5, 0.083). The one weakness that stands out is related to additional costs and food safety issues between production cycles (mW1, 0.054), while the interdependence between provider and producer is the main threat to consider (mT2 0.041). An overview of the SWOT-AHP analysis for the mobile packaging scenario can be found in Annex 1.

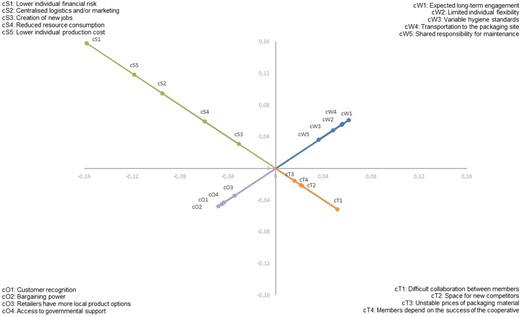

Figure 4 illustrates the proportions of the global priority scores for the cooperative. The cooperative scenario is defined by the strengths related to the lower individual financial risk (cS1, 0.158), the lower individual production cost (cS5, 0.118) and the possibility to create centralised logistics and marketing (cS2, 0.095). The long-term engagement of the individual members (cW1, 0.061), the commitment of the producers to transport their product to the packaging site (cW4, 0.056) and the limited individual flexibility (cW2, 0.055) have the highest negative impact on the perception of the scenario. Followed by the threat based on difficult collaboration between members (cT1, 0.052). Most opportunities of the scenario are clustered, focused on increasing bargaining power (cO2, 0.048), customer recognition (cO1, 0.045) and access to governmental support (cO4, 0.043). An overview of the SWOT-AHP analysis for the cooperative scenario can be found in Annex 2.

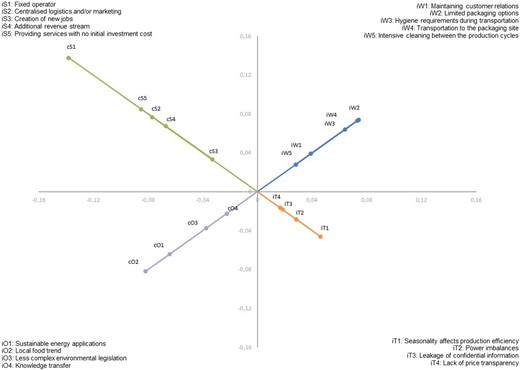

The proportions of the global priority scores for individual ownership are shown in Fig. 5. The largest strength of the individual ownership scenario is related to the fixed operator on site (iS1, 0.138), followed by the absence of investment costs for the users (iS5, 0.085) and possible collaboration through centralised logistics and marketing (iS2, 0.77). Small processors highly value the opportunity to use this scenario in light of sustainability trends related to local food (iO2, 0.082). Two weaknesses are clustered with a similar high impact, related to food safety issues during transportation (iW3, 0.074) and the limited packaging options (iW2, 0.073). The threat with the most impact on the perception of the scenario is related to the availability of the machine during peak season (iT1, 0.046). An overview of the SWOT-AHP analysis for the individual ownership scenario can be found in Annex 3.

Next to the generation of local and global priority scores, the study was designed to indicate the relative importance of the scenarios within the case study resulting in the scenario priority score. The scenario priority score indicates the overall stakeholder preference for a certain scenario. The scenario priority scores are shown in Fig. 6, together with the positive perception of each scenario. The scores confirm the mobile packaging scenario as the preferred scenario of the stakeholders. The positive scaling factors of the scenarios did not show a clear difference in perception between the cooperative scenario and the individual ownership scenario. Looking at the scenario priority scores, a preference for the cooperative scenario over individual ownership is present. This preference is the result of comparing the scenarios within the context of the case study with each other, rather than analysing the scenario solely based on the SWOT factors.

Priority scores for three collaborative business scenarios (mobile packaging machine, cooperative and individual ownership). The outer ring shows the preference for the scenarios based on the scenario priority score, and the inner ring shows the perception of the scenarios based on the SWOT-AHP scaling factors.

Discussion

Analysing different scenarios in a case study using SWOT-AHP provides insights into stakeholder perceptions for the implementation of different business scenarios and helps to identify and better understand the most preferred scenario. Small-scale processing stakeholders defined appropriate scenarios for the case study, supporting previous findings in the literature on the collaborative nature of scaling-up SFSC (Clark & Inwood, 2016). The case study focuses on improved food safety in small-scale processing by introducing the concept of a flexible, aseptic filling machine that addresses the need for adapted equipment (Badraoui et al., 2020).

Small processors focused on factors related to business operations such as operator efficiency, alleged financial benefits and effective logistics management. A fixed operator to guarantee hygienic and operational requirements when sharing processing equipment was a crucial factor for the mobile and individual ownership scenario, but was not reported in the cooperative scenario, suggesting that cooperative members still bear responsibility for the packaging machine. Emphasising the possibility of a fixed operator in the cooperative scenario could improve its adoption in SFSC. The need for a fixed operator is linked with food safety concerns, which is known to limit collaborations in agri-food chains (Badraoui et al., 2020). High-level small-scale processing equipment can help to improve the food safety and hygienic standards in these chains and make them more competitive (Bramsiepe et al., 2012; Buckley, 2015). When sharing processing equipment, the scenarios show negatively perceived aspects either related to the cost and logistics of intensive cleaning between production cycles, the sensitivity of transporting raw material or variable hygiene standards among different producers.

Due to the external focus of the cooperative and individual ownership scenarios, both can benefit from centralised logistics and marketing strategies. Successful collaborative SFSC development relies on efficient logistics management (EIP-Agri, 2015), but there is untapped potential for marketing and product development (Bianchi, 2010). Small firms' marketing competencies may be more critical to their success than production-related competencies, particularly when seeking to expand their business (Forsman, 2004). When developing and implementing equipment for small processors, flexibility regarding the type of products and use of the equipment should be kept in mind (Bramsiepe et al., 2012). Flexibility is referred to in the scenarios in terms of use, limitations and interdependence. In case of the mobile packaging scenario, flexibility has high relative importance as it offers processors the opportunity to use the machine without any financial commitment. Lower investment costs to access high-level processing technology, are crucial factors in all scenarios. This is in line with the findings of Badraoui et al. (2020) who stated that sharing technical resources due to high investment costs is one of the main drivers for collaboration in agri-food chains. The interaction between the collaborative and financial aspects may result in lower production costs, which is a highly valued factor in the cooperative scenario.

Collaborative factors appear in the scenarios in various forms, either internally (cooperative) or externally (mobile packaging, individual ownership). The mobile packaging scenario, which has the strongest stakeholder preference, is highly positively perceived in terms of collaborative opportunities. However, there is also a risk of interdependence between the service company and producers that could threaten the mobile packaging scenario, but this risk is considered relatively less important than the opportunities the scenario creates. Collaborative scenarios can be perceived with both constructive and deconstructive power relations. When collaborations occur externally threats related to interdependencies and power imbalances between supply chain actors occur, while producers in cooperatives should capitalise on the increased bargaining power towards suppliers and access to retailers.

Conclusion

The purpose of the present research was to examine different collaborative scenarios within a case study using SWOT-AHP, to gain a deeper understanding of stakeholder perceptions and identify the most preferred scenario for a high-level aseptic filling machine when scaling-up SFSC. The main factors for stakeholders to engage in collaborative scenarios were the perceived financial benefits for individual small processors. When implementing collaborative scenarios for processing equipment, actors should anticipate how to maximise flexibility options, put emphasis on the role of the fixed operator and consider including centralised logistics and marketing.

Depending on the type of collaboration, stakeholders should concentrate on specific aspects. Regarding the mobile packaging scenario, the focus should lie on the flexibility and collaborative opportunities the machine creates while keeping in mind the intensive cleaning process and interdependence between a service provider and a user. The cooperative scenario can capitalise on centralised logistics and marketing and a better market position. The cooperation should be careful of the structure of the cooperative to stimulate long-term engagement and fruitful collaborations while trying to eliminate logistics and flexibility-related limitations. When implementing the individual ownership scenario, centralised logistics and marketing should also be a point of attention, while focusing the marketing aspects on local food trends, keeping in mind the food safety and flexibility limitations.

The study examined the implementation of small-scale processing equipment to support scaling-up SFSC. Applying SWOT-AHP to analyse multiple scenarios within one case study, introducing the scenario priority score, is a novelty in its field. Future research should explore including cost and investment analysis and setting stricter limitations in the number of SWOT factors, to consider the high cognitive burden for the respondents when analysing multiple scenarios within one case study. The study contributed to small-scale food processing research and can provide a basis for further collaborations in SFSC.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge that this paper is a result of the work carried out of the FAIRCHAIN project, which received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 101000723.

Author contributions

Esther Van Parys: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); project administration (lead); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead). Duc Tran: Conceptualization (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); project administration (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Imca Sampers: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); investigation (supporting); project administration (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Thierry Benezech: Conceptualization (supporting); investigation (supporting); project administration (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Pieter-Jan Loveniers: Conceptualization (supporting); investigation (supporting); project administration (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Frank Devlieghere: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Hans De Steur: Conceptualization (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Xavier Gellynck: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (equal); methodology (supporting); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Joachim J. Schouteten: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); funding acquisition (equal); methodology (supporting); project administration (supporting); supervision (lead); writing – review and editing (lead).

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest are declared.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not required for this research.

Peer review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/ijfs.16551.

Data availability statement

Research data are not shared due to ethical restrictions. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, EVP, upon request. All authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript. Furthermore, the authors would like to confirm that this manuscript is not under consideration at another journal.

References

They state both issue of food safety concerns in agri-food supply chains when collaborating and identified costly equipment as a driver for collaboration, which are two of the main elements which resulted from our workshops.

They analysed scaling-up regional production and distribution and validated the interest of stakeholders for further market development with collaboration amongst stakeholders as a key item.

This study was the first to use the SWOT-AHP methodology which is used in this study. This study expands the methodology used in the reference to create another level in the analysis.

They conceptualised the AHP method, which in this paper is used as the extension for SWOT.

Annex 1

Local and global priority scores of the SWOT-AHP analysis for the mobile packaging scenario

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.459 | |

| mS1: Fixed operator | 0.319 | 0.146 |

| mS2: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.295 | 0.135 |

| mS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.065 | 0.030 |

| mS4: Avoids transportation costs for raw material | 0.134 | 0.061 |

| mS5: Offers flexibility to producers | 0.182 | 0.083 |

| Weaknesses | 0.141 | |

| mW1: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.386 | 0.054 |

| mW2: Limited packaging options | 0.210 | 0.030 |

| mW3: Resource management on site | 0.143 | 0.020 |

| mW4: Limited availability during peak season | 0.172 | 0.024 |

| mW5: Transportation impacts sustainability performance | 0.088 | 0.012 |

| Opportunities | 0.293 | |

| mO1: Collaborations between producers | 0.340 | 0.100 |

| mO2: Sustainability trends | 0.217 | 0.064 |

| mO3: Protection of confidential information for the producer | 0.130 | 0.038 |

| mO4: Expansion of the stakeholder network | 0.116 | 0.034 |

| mO5: Creating accessibility for small actors | 0.197 | 0.058 |

| Threats | 0.107 | |

| mT1: Unstable prices for packaging material | 0.222 | 0.024 |

| mT2: Interdependence between service provider and producers | 0.386 | 0.041 |

| mT3: Competitors can take advantage of the service | 0.134 | 0.014 |

| mT4: Traffic jams interrupt production cycles | 0.157 | 0.017 |

| mT5: Unstable fuel prices | 0.101 | 0.011 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.459 | |

| mS1: Fixed operator | 0.319 | 0.146 |

| mS2: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.295 | 0.135 |

| mS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.065 | 0.030 |

| mS4: Avoids transportation costs for raw material | 0.134 | 0.061 |

| mS5: Offers flexibility to producers | 0.182 | 0.083 |

| Weaknesses | 0.141 | |

| mW1: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.386 | 0.054 |

| mW2: Limited packaging options | 0.210 | 0.030 |

| mW3: Resource management on site | 0.143 | 0.020 |

| mW4: Limited availability during peak season | 0.172 | 0.024 |

| mW5: Transportation impacts sustainability performance | 0.088 | 0.012 |

| Opportunities | 0.293 | |

| mO1: Collaborations between producers | 0.340 | 0.100 |

| mO2: Sustainability trends | 0.217 | 0.064 |

| mO3: Protection of confidential information for the producer | 0.130 | 0.038 |

| mO4: Expansion of the stakeholder network | 0.116 | 0.034 |

| mO5: Creating accessibility for small actors | 0.197 | 0.058 |

| Threats | 0.107 | |

| mT1: Unstable prices for packaging material | 0.222 | 0.024 |

| mT2: Interdependence between service provider and producers | 0.386 | 0.041 |

| mT3: Competitors can take advantage of the service | 0.134 | 0.014 |

| mT4: Traffic jams interrupt production cycles | 0.157 | 0.017 |

| mT5: Unstable fuel prices | 0.101 | 0.011 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.459 | |

| mS1: Fixed operator | 0.319 | 0.146 |

| mS2: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.295 | 0.135 |

| mS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.065 | 0.030 |

| mS4: Avoids transportation costs for raw material | 0.134 | 0.061 |

| mS5: Offers flexibility to producers | 0.182 | 0.083 |

| Weaknesses | 0.141 | |

| mW1: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.386 | 0.054 |

| mW2: Limited packaging options | 0.210 | 0.030 |

| mW3: Resource management on site | 0.143 | 0.020 |

| mW4: Limited availability during peak season | 0.172 | 0.024 |

| mW5: Transportation impacts sustainability performance | 0.088 | 0.012 |

| Opportunities | 0.293 | |

| mO1: Collaborations between producers | 0.340 | 0.100 |

| mO2: Sustainability trends | 0.217 | 0.064 |

| mO3: Protection of confidential information for the producer | 0.130 | 0.038 |

| mO4: Expansion of the stakeholder network | 0.116 | 0.034 |

| mO5: Creating accessibility for small actors | 0.197 | 0.058 |

| Threats | 0.107 | |

| mT1: Unstable prices for packaging material | 0.222 | 0.024 |

| mT2: Interdependence between service provider and producers | 0.386 | 0.041 |

| mT3: Competitors can take advantage of the service | 0.134 | 0.014 |

| mT4: Traffic jams interrupt production cycles | 0.157 | 0.017 |

| mT5: Unstable fuel prices | 0.101 | 0.011 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.459 | |

| mS1: Fixed operator | 0.319 | 0.146 |

| mS2: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.295 | 0.135 |

| mS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.065 | 0.030 |

| mS4: Avoids transportation costs for raw material | 0.134 | 0.061 |

| mS5: Offers flexibility to producers | 0.182 | 0.083 |

| Weaknesses | 0.141 | |

| mW1: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.386 | 0.054 |

| mW2: Limited packaging options | 0.210 | 0.030 |

| mW3: Resource management on site | 0.143 | 0.020 |

| mW4: Limited availability during peak season | 0.172 | 0.024 |

| mW5: Transportation impacts sustainability performance | 0.088 | 0.012 |

| Opportunities | 0.293 | |

| mO1: Collaborations between producers | 0.340 | 0.100 |

| mO2: Sustainability trends | 0.217 | 0.064 |

| mO3: Protection of confidential information for the producer | 0.130 | 0.038 |

| mO4: Expansion of the stakeholder network | 0.116 | 0.034 |

| mO5: Creating accessibility for small actors | 0.197 | 0.058 |

| Threats | 0.107 | |

| mT1: Unstable prices for packaging material | 0.222 | 0.024 |

| mT2: Interdependence between service provider and producers | 0.386 | 0.041 |

| mT3: Competitors can take advantage of the service | 0.134 | 0.014 |

| mT4: Traffic jams interrupt production cycles | 0.157 | 0.017 |

| mT5: Unstable fuel prices | 0.101 | 0.011 |

Annex 2

Local and global priority scores of the SWOT-AHP analysis for the cooperative scenario

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.464 | |

| cS1: Lower individual financial risk | 0.341 | 0.158 |

| cS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.204 | 0.095 |

| cS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.066 | 0.031 |

| cS4: Reduced resource consumption | 0.128 | 0.059 |

| cS5: Lower individual production cost | 0.255 | 0.118 |

| Weaknesses | 0.255 | |

| cW1: Expected long-term engagement | 0.239 | 0.061 |

| cW2: Limited individual flexibility | 0.215 | 0.055 |

| cW3: Variable hygiene standards | 0.186 | 0.048 |

| cW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.219 | 0.056 |

| cW5: Shared responsibility for maintenance | 0.141 | 0.036 |

| Opportunities | 0.170 | |

| cO1: Customer recognition | 0.265 | 0.045 |

| cO2: Bargaining power | 0.282 | 0.048 |

| cO3: Retailers have more local product options | 0.201 | 0.034 |

| cO4: Access to governmental support | 0.253 | 0.043 |

| Threats | 0.110 | |

| cT1: Difficult collaboration between members | 0.468 | 0.052 |

| cT2: Space for new competitors | 0.200 | 0.022 |

| cT3: Unstable prices of packaging material | 0.142 | 0.016 |

| cT4: Members depend on the success of the cooperative | 0.190 | 0.021 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.464 | |

| cS1: Lower individual financial risk | 0.341 | 0.158 |

| cS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.204 | 0.095 |

| cS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.066 | 0.031 |

| cS4: Reduced resource consumption | 0.128 | 0.059 |

| cS5: Lower individual production cost | 0.255 | 0.118 |

| Weaknesses | 0.255 | |

| cW1: Expected long-term engagement | 0.239 | 0.061 |

| cW2: Limited individual flexibility | 0.215 | 0.055 |

| cW3: Variable hygiene standards | 0.186 | 0.048 |

| cW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.219 | 0.056 |

| cW5: Shared responsibility for maintenance | 0.141 | 0.036 |

| Opportunities | 0.170 | |

| cO1: Customer recognition | 0.265 | 0.045 |

| cO2: Bargaining power | 0.282 | 0.048 |

| cO3: Retailers have more local product options | 0.201 | 0.034 |

| cO4: Access to governmental support | 0.253 | 0.043 |

| Threats | 0.110 | |

| cT1: Difficult collaboration between members | 0.468 | 0.052 |

| cT2: Space for new competitors | 0.200 | 0.022 |

| cT3: Unstable prices of packaging material | 0.142 | 0.016 |

| cT4: Members depend on the success of the cooperative | 0.190 | 0.021 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.464 | |

| cS1: Lower individual financial risk | 0.341 | 0.158 |

| cS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.204 | 0.095 |

| cS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.066 | 0.031 |

| cS4: Reduced resource consumption | 0.128 | 0.059 |

| cS5: Lower individual production cost | 0.255 | 0.118 |

| Weaknesses | 0.255 | |

| cW1: Expected long-term engagement | 0.239 | 0.061 |

| cW2: Limited individual flexibility | 0.215 | 0.055 |

| cW3: Variable hygiene standards | 0.186 | 0.048 |

| cW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.219 | 0.056 |

| cW5: Shared responsibility for maintenance | 0.141 | 0.036 |

| Opportunities | 0.170 | |

| cO1: Customer recognition | 0.265 | 0.045 |

| cO2: Bargaining power | 0.282 | 0.048 |

| cO3: Retailers have more local product options | 0.201 | 0.034 |

| cO4: Access to governmental support | 0.253 | 0.043 |

| Threats | 0.110 | |

| cT1: Difficult collaboration between members | 0.468 | 0.052 |

| cT2: Space for new competitors | 0.200 | 0.022 |

| cT3: Unstable prices of packaging material | 0.142 | 0.016 |

| cT4: Members depend on the success of the cooperative | 0.190 | 0.021 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.464 | |

| cS1: Lower individual financial risk | 0.341 | 0.158 |

| cS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.204 | 0.095 |

| cS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.066 | 0.031 |

| cS4: Reduced resource consumption | 0.128 | 0.059 |

| cS5: Lower individual production cost | 0.255 | 0.118 |

| Weaknesses | 0.255 | |

| cW1: Expected long-term engagement | 0.239 | 0.061 |

| cW2: Limited individual flexibility | 0.215 | 0.055 |

| cW3: Variable hygiene standards | 0.186 | 0.048 |

| cW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.219 | 0.056 |

| cW5: Shared responsibility for maintenance | 0.141 | 0.036 |

| Opportunities | 0.170 | |

| cO1: Customer recognition | 0.265 | 0.045 |

| cO2: Bargaining power | 0.282 | 0.048 |

| cO3: Retailers have more local product options | 0.201 | 0.034 |

| cO4: Access to governmental support | 0.253 | 0.043 |

| Threats | 0.110 | |

| cT1: Difficult collaboration between members | 0.468 | 0.052 |

| cT2: Space for new competitors | 0.200 | 0.022 |

| cT3: Unstable prices of packaging material | 0.142 | 0.016 |

| cT4: Members depend on the success of the cooperative | 0.190 | 0.021 |

Annex 3

Local and global priority scores of the SWOT-AHP analysis for the individual ownership scenario

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.407 | |

| iS1: Fixed operator | 0.338 | 0.138 |

| iS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.189 | 0.077 |

| iS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.082 | 0.033 |

| iS4: Additional revenue stream | 0.166 | 0.067 |

| iS5: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.209 | 0.085 |

| Weaknesses | 0.278 | |

| iW1: Maintaining customer relations | 0.139 | 0.039 |

| iW2: Limited packaging options | 0.264 | 0.073 |

| iW3: Hygiene requirements during transportation | 0.267 | 0.074 |

| iW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.230 | 0.064 |

| iW5: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.100 | 0.028 |

| Opportunities | 0.206 | |

| iO1: Sustainable energy applications | 0.312 | 0.064 |

| iO2: Local food trend | 0.397 | 0.082 |

| iO3: Less complex environmental legislation | 0.181 | 0.037 |

| iO4: Knowledge transfer | 0.109 | 0.022 |

| Threats | 0.109 | |

| iT1: Seasonality affects production efficiency | 0.421 | 0.046 |

| iT2: Power imbalances | 0.260 | 0.028 |

| iT3: Leakage of confidential information | 0.168 | 0.018 |

| iT4: Lack of price transparency | 0.151 | 0.016 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.407 | |

| iS1: Fixed operator | 0.338 | 0.138 |

| iS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.189 | 0.077 |

| iS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.082 | 0.033 |

| iS4: Additional revenue stream | 0.166 | 0.067 |

| iS5: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.209 | 0.085 |

| Weaknesses | 0.278 | |

| iW1: Maintaining customer relations | 0.139 | 0.039 |

| iW2: Limited packaging options | 0.264 | 0.073 |

| iW3: Hygiene requirements during transportation | 0.267 | 0.074 |

| iW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.230 | 0.064 |

| iW5: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.100 | 0.028 |

| Opportunities | 0.206 | |

| iO1: Sustainable energy applications | 0.312 | 0.064 |

| iO2: Local food trend | 0.397 | 0.082 |

| iO3: Less complex environmental legislation | 0.181 | 0.037 |

| iO4: Knowledge transfer | 0.109 | 0.022 |

| Threats | 0.109 | |

| iT1: Seasonality affects production efficiency | 0.421 | 0.046 |

| iT2: Power imbalances | 0.260 | 0.028 |

| iT3: Leakage of confidential information | 0.168 | 0.018 |

| iT4: Lack of price transparency | 0.151 | 0.016 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.407 | |

| iS1: Fixed operator | 0.338 | 0.138 |

| iS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.189 | 0.077 |

| iS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.082 | 0.033 |

| iS4: Additional revenue stream | 0.166 | 0.067 |

| iS5: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.209 | 0.085 |

| Weaknesses | 0.278 | |

| iW1: Maintaining customer relations | 0.139 | 0.039 |

| iW2: Limited packaging options | 0.264 | 0.073 |

| iW3: Hygiene requirements during transportation | 0.267 | 0.074 |

| iW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.230 | 0.064 |

| iW5: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.100 | 0.028 |

| Opportunities | 0.206 | |

| iO1: Sustainable energy applications | 0.312 | 0.064 |

| iO2: Local food trend | 0.397 | 0.082 |

| iO3: Less complex environmental legislation | 0.181 | 0.037 |

| iO4: Knowledge transfer | 0.109 | 0.022 |

| Threats | 0.109 | |

| iT1: Seasonality affects production efficiency | 0.421 | 0.046 |

| iT2: Power imbalances | 0.260 | 0.028 |

| iT3: Leakage of confidential information | 0.168 | 0.018 |

| iT4: Lack of price transparency | 0.151 | 0.016 |

| SWOT categories and factors . | Local priority score . | Global priority score . |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 0.407 | |

| iS1: Fixed operator | 0.338 | 0.138 |

| iS2: Centralised logistics and/or marketing | 0.189 | 0.077 |

| iS3: Creation of new jobs | 0.082 | 0.033 |

| iS4: Additional revenue stream | 0.166 | 0.067 |

| iS5: Providing services with no initial investment cost | 0.209 | 0.085 |

| Weaknesses | 0.278 | |

| iW1: Maintaining customer relations | 0.139 | 0.039 |

| iW2: Limited packaging options | 0.264 | 0.073 |

| iW3: Hygiene requirements during transportation | 0.267 | 0.074 |

| iW4: Transportation to the packaging site | 0.230 | 0.064 |

| iW5: Intensive cleaning between the production cycles | 0.100 | 0.028 |

| Opportunities | 0.206 | |

| iO1: Sustainable energy applications | 0.312 | 0.064 |

| iO2: Local food trend | 0.397 | 0.082 |

| iO3: Less complex environmental legislation | 0.181 | 0.037 |

| iO4: Knowledge transfer | 0.109 | 0.022 |

| Threats | 0.109 | |

| iT1: Seasonality affects production efficiency | 0.421 | 0.046 |

| iT2: Power imbalances | 0.260 | 0.028 |

| iT3: Leakage of confidential information | 0.168 | 0.018 |

| iT4: Lack of price transparency | 0.151 | 0.016 |