-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Robin P Choudhury, The Beating Heart: art meets science in the story of the heart, Cardiovascular Research, 2025;, cvaf054, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvaf054

Close - Share Icon Share

1. Introduction

From time to time, I am asked why I became a cardiologist and cardiovascular researcher. At some level, the answer is easy—a simple conviction that the heart is ‘the most important bit’. The Beating Heart (Head of Zeus/Bloomsbury, 2024; Figure 1A) is my long overdue exploration of why I, and so many others over the centuries, have felt this way.1

When the philosopher and proto-scientist Aristotle sought the origin of life, he lifted a flap in a fertilized chick egg. There, he saw the beating embryonic heart, self-evidently the prime mover and originator of life. The heart was at the very centre of Aristotle’s interpretation of the operations of living things. But Aristotle was far from alone, the heart has been revered, celebrated, worshipped, and offered in acts of devotion and love across many cultures. The attributes afforded to the heart have been remarkably consistent. The heart emerges as the dwelling place of the soul, the source of life, the seat of love, the recorder of deeds, and an abode for gods. In references as diverse as the ancient Indian verses of the Upanishads and the Galen-inspired early drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, the heart was even believed to be the source of semen.

Over the ages, notions of the heart and its properties have been richly represented in visual images, which do not merely ornament the story, but are integral to it. The ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead records on papyrus scrolls the ceremony of Ma’at and the weighing of the heart as part of the process of judgement. Images of the ceremonial rites of the Aztec tradition show hearts being explanted from the living and dispatched to the sky as an offering to the Sun God. From Bengal, Kalighat art depictions of the Ramayana, show Ram and Sita residing in the heart of Hanuman, the monkey god. In western sacred art of the early 14th century, Giotto painted (in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua) an anatomically faithful heart that is shown passing between the hands of the ‘virtue’ Charity and God, while Sandro Botticelli recorded the mystery in the incision of the heart of Saint Ignatius. In a striking secular demonstration of chivalric love, the 15th century engraver Casper von Regensburg depicted the broken, punctured, burning, fragmented hearts of a tortured suitor crouched before the object of his desire, Frau Minne.

Early thinkers did not delineate the mechanistic and functional aspects of the heart that are second nature in our reductionist age. How the heart worked, what it did, and why were rolled into a general quest to understand the natural world. Thirteenth century priest and scholar, Thomas Aquinas had been important in reconciling the teaching of the classical texts with contemporary Christian doctrine and was one of the first to articulate why the heart is uniquely regarded. Aquinas recognized that the heart is a prime mover—autonomous in the generation of its beat, that it operates with no conscious input but is responsive, moved by the soul. It is as if the heart exists as entity that operates within us, but apart from us.

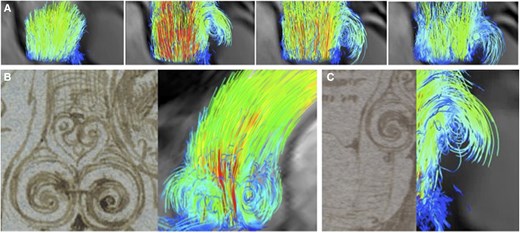

Leonardo da Vinci had inherited a rigid knowledge base from the texts of Galen, Hippocrates, and the classical scholars but, in the spirit of his time, transformed his approach towards systematic evaluation from personal observation, elaborated by actual experimentation, and recorded in hundreds of pages of notebooks. My own fascination with this topic was fuelled by Leonardo and our own work, using 4D-MRI to confirm his theories on the flow vortices in the aortic root. The in vivo confirmation of Leonardo’s work was published in the European Heart Journal in 2013, exactly 500 years after Leonardo’s meticulous, but private description (Figure 1B).2 The Beating Heart tells how Leonardo’s previously unpublished anatomical notebooks were dramatically revealed in a lecture by William Hunter in 1794.

Flow vortices in the aortic root. (A) Sequential images of the flow in the aortic root using velocity encoded (4D) MRI showing laminar flow early in systole with laterally placed vortices in late systole. (B and C) Comparison of the drawings of flow vortices visualized by Leonardo da Vinci (1513) (left) with the corresponding in vivo 4D-MRI (2013) (right), confirming Leonardo’s predictions.

Mainstream anatomical inquiry took hold in the early universities: in Paris, Bologna, Marburg, and, most notably, Padua. In Padua, William Harvey studied under Fabricius (after Vesalius) and there learnt of the valves in veins that, above all, he said, had underpinned his novel theories on the circulation of the blood. Throughout the book, I have tried to couch ‘scientific’ discovery, alongside the prevailing cultural, spiritual, and philosophical currents, and to show how the possibilities for new understanding were in lockstep with the prevailing intellectual landscape of the day. For instance, Aquinas conceived of the heart with reference to the movement of the planets; Harvey, in an age of early mechanization, was able to imagine the heart as a pump, and later investigators were moved to investigate its electrical properties.

On reading Harvey’s theories on the circulation of blood, philosopher, mathematician, and physiologist René Descartes accepted the new paradigm, but recognized that much deeper problem remained—how does the heart beat for itself? His question remained out of reach for 300 years. From the early 18th century onwards, there was a startling transfer of heart images from the anatomists to the Catholic scholars. It was the carnal, fleshy anatomical heart (rather than some quaint heart motif) that became the symbol of the Sacred Heart. But how did that transplant occur and spread across the world? Remarkably, we can track it down to the single image that formed the basis for the propagation of anatomical forms of the heart around the Catholic world. Fast forward, the heart permeates the work of modern artists from Picasso, Matisse, Miro, and Dali to the most passionate and emotive depicter of hearts—Frida Kahlo.

Throughout recorded history, fascination with the heart has revolved around its autonomous BEAT. So, hunting history of the beat was key. A personal highlight in the writing was to have had an opportunity and privilege to share my interview with Professor Denis Noble. As a graduate student at the University College London, he had (through a combination of experimentation and early computation) figured out the generation of the cardiac pacemaker potential and published in a single-author letter to Nature in 1960.3 How did it feel to have cracked the problem that had so perplexed thinkers from Aristotle to Aquinas, Descartes, and Pascal? Did he realize that he had solved Aristotle’s constructs of the very origin of life?

Ideas around the heart turned out to be even more pervasive and enduring than I had imagined. The heart has held such timeless prominence in our collective thinking (and intuitions) that its story illuminates a much broader cultural and intellectual history. I have tried to capture our timeless enthralled engagement sense of enduring wonder in my telling of this story of The Beating Heart.

Funding

Professor Choudhury receives support from the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence, Oxford.

Data availability

There are no data in this commentary.

References

Author

Robin Choudhury is a professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, Fellow of Balliol College, and a practising cardiologist. He trained in Oxford, London, and Mount Sinai, New York. His clinical expertise is in the emergency treatment of heart attack. He also heads a laboratory working on molecular and cellular mechanisms of heart injury and repair. He has a particular interest in the role of ‘inflammation’ in cardiovascular diseases. He is a Fellow of Balliol College and of the Royal College of Physicians and is a former Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow. He has published over 250 academic papers and book chapters. He is co-editor of the Handbook of Cardiology Emergencies (OUP) and contributor to the Oxford Textbook of Medicine (OUP). He has a lifelong passion for the visual arts. In 2013, he led a group at the Oxford Acute Vascular Imaging Centre (of which he was founding director) that used MRI to test, for the first time in a living subject, the 500-year-old theories of Leonardo da Vinci on the movement of blood across the aortic valve. He lives in London and Oxford with Jasmine Dellal, a documentary film maker.

Author notes

Conflict of interest: none declared.