-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Prakrit Raj Kumar, Yousuf Hashmi, Raimand Morad, Varun Dewan, Clinical Audit Platform for Students (CAPS): a pilot study, Postgraduate Medical Journal, Volume 97, Issue 1151, September 2021, Pages 571–576, https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138426

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

A clinical audit measures specific clinical outcomes or processes against a predefined standard. However, many clinicians are unable to carry out audits given their time constraints. Alternatively, medical students may often wish to complete audits early in their career to strengthen their portfolios. As such, the student clinical audit platform was designed to connect willing supervisors and these medical students.

Project supervisors were members of a regional trainee-led network. Interested students were familiarised with the various aspects of an audit and allocated to supervisors with similar interests. There was regular communication to track progress and anonymised feedback forms were distributed to all students and supervisors after a year.

A total of 17 responses were received from the 19 students who were involved in a project. Based on a 5-point Likert scale, students displayed a mean improvement in their understanding of a clinical audit (1.18±1.07, p<0.001), the confidence to approach a supervisor (1.29±1.21, p<0.001) and the ability to conduct an audit by themselves in the future (1.77±1.15, p<0.001). Of the seven affiliated supervisors, five provided feedback with 80% indicating they had projects which remained inactive and all happy with the quality of work produced by their students.

Despite limitations to this programme, the platform produced projects which were disseminated both locally and nationally, demonstrating positive collaboration between medical students and clinicians. We present our findings and evaluations to encourage similar audit platforms to be adopted at other locations.

INTRODUCTION

A clinical audit measures a specific clinical outcome or process against a predefined standard. These standards may be set by regulators at a local, regional or national level to ultimately improve the quality of patient care within the National Health Service (NHS).1 The process of carrying out an audit involves a continuous and cyclical framework. Following an initial audit cycle, quality improvement (QI) strategies aimed at improving standards are introduced and data is again collected to evaluate the success of the interventions. Moreover, the constant technological advances in medical equipment over the last decade have caused a rapid change in clinical practice. Clinical audits are essential in the learning and implementation of new technology into clinical use,2 as results are shared, decreasing occurrence of mistakes and translating into better standards of care nationally.3 The public inquiry into the high mortality rate following paediatric cardiac surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary in 1984–1995 is a well-documented failure in the UK healthcare delivery service; to prevent such catastrophes from occurring again, the Department of Health highlighted the importance of regular clinical audits at the core of a local performance monitoring system.4 Thus, the importance of audit and QI projects is now recognised and firmly established.5

Within the UK, consultants and junior doctors are required to complete regular clinical audits as part of the General Medical Council’s ‘Good Medical Practice’ guidance.6 Despite many centres having a dedicated audit department overseeing the logistics, clinicians still struggle to complete clinical audits regularly. Initial studies highlight that the barriers to successful implementation of clinical audits are time constraints, support of staff and logistical barriers.7 Clinicians often have ideas for projects, but demanding rotas often hinder their progress.8 Thus, many delegate certain tasks such as data collection, analysis and reauditing.

Despite strong motivations to participate in audit projects, many students do not complete them before graduating. Current literature has identified several practical barriers that prevent medical students from doing so, including lack of opportunity, hostile hospital culture and insufficient base knowledge.9–11 Students are often unsure of how to contact a potential supervisor for an audit, due to fear of rejection. The finding of audit projects with supervisors working in a speciality of interest is usually down to chance. In one study, 107 of the 238 student participants felt that not asking the right person was a major barrier.12 Further, the lack of knowledge of students13 in conducting a clinical audit only exacerbates the issue, where supervisors are less inclined to supervise students who do not have prior audit knowledge. Chapman et al showed that 63% of students reported lack of interest from supervisors as one of the main barriers in obtaining a project.12 Thus, an undesirable cycle of inopportunity to undertake clinical audits is created among medical students.14

A platform was therefore required to provide a bridge between clinicians and motivated medical students. The Birmingham Orthopaedic Network (BON), a regional trainee-led collaborative organisation, initially piloted such a platform and developed the infrastructure to allow collaboration on their audit and research projects. Our Clinical Audit Platform for Students (CAPS) addressed the lack of a similar framework in place at the medical school. Where implementation of CAPS requires effective organisation from both the medical students and the trainees, our initiative identified motivated medical students and equipped them with the knowledge of how to conduct clinical audits as well as improving their confidence to carry them out. The aim of the platform was to synergistically benefit students, clinicians and the healthcare provided to patients.

METHODS

The platform was designed by a medical school Trauma and Orthopaedic (T&O) society, using the infrastructure provided by the BON. Initially, a PowerPoint-driven lecture was delivered to all interested medical students to familiarise them with the various aspects of an audit including the definition, process and importance of completing the audit loop. This provided medical students with the necessary knowledge to undertake an audit, reducing this burden from the supervisors and thereby encouraging more audit opportunities for all.

Following the session, students had the opportunity to fill out an ‘Audit Request’ Form (online appendix 1), in order to register their interest in the next phase of the programme. Allocation was implemented in collaboration with the BON, who facilitated orthopaedic speciality trainees to act as supervisors. The advantage of doing so was that the audit programme spanned over several trusts, in contrast to local Research and Development (R&D) audit departments. Supervisors indicated the number of projects that they required assistance with and their respective subspeciality areas. Students also listed their specific interests within T&O and were matched to supervisors with similar interests. Allocations and contact details were emailed to both parties.

To ensure that continuous support was provided to the students, students were encouraged to include the CAPS programme administrators in all correspondence or approach them directly should they have any questions, to be resolved on a case-by-case basis. To ensure successful completion of audits, students were asked to complete two different forms: an ‘Audit Proposal’ form (online appendix 2) outlining their project and respective aims and an ‘Audit completion’ form (online appendix 3) to ensure successful documentation for their portfolio. A master Excel spreadsheet was maintained to ensure regular monitoring of the students.

An anonymous feedback questionnaire was distributed to students (online appendix 4) and supervisors (online appendix 5) to

Assess their knowledge and practical implications to their audits, prior and after the audit programme.

Understand their experience.

Obtain constructive feedback and recommendations for future improvements.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were generated using Graphpad Prism5 software (Graphpad, San Diego, California, USA). The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to compare Likert scale scores prior and after audit programme, with p<0.05*, p<0.01** and p<0.001*** considered as statistically significant. Results are presented as the mean±SD.

Ethical considerations

The project protocol was processed through the NHS Health Research Authority and a copy of the corresponding report is presented in online appendix 6.15 The feedback received was that this project is not considered as ‘Research’. As such, this study was exempt from an Institutional Review Board ethical approval, which is the case with similar publications pertaining to participant evaluations.16 17 Indeed, this study was conducted in accordance with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) ethical principles and the UK Data Protection Act, 2018c. 12.18 19 Prior consent was obtained from all participants to use their data for research purposes. Proper and strict confidentiality procedures were employed in the data handling of this project to maintain anonymity and all sensitive data was protected from accidental loss or unauthorised access by storing them according to the University of Birmingham organisational measures.

RESULTS

Analytical sample

With an initial response rate of 78 students and 30 signing up to the programme, 19 students started an audit project (figure 1). Questionnaires were sent to all of these 19 students. Of the 17 students that responded, 8 had fully completed their audit and the remainder had only partially completed them. Prior to the programme, 35.3% of the students had a definite interest in T&O as a future career and 58.8% of the students were unsure about their commitment to T&O. Following the programme, 70.6% of the participants said to be inspired to pursue a career in T&O.

Flow chart depicting the number of participants involved during all stages of the Clinical Audit Platform for Students.

Preprogramme

Although 94.1% of the participants understood the importance of carrying out audits for both quality of patient care and in improving their own future careers, it was found that 82.3% of the students were not confident in carrying out an audit by themselves and 58.8% were not confident enough to approach supervisors for a clinical audit project. Furthermore, 58.8% of the students were unable to define clinical audit prior to the programme.

Postprogramme

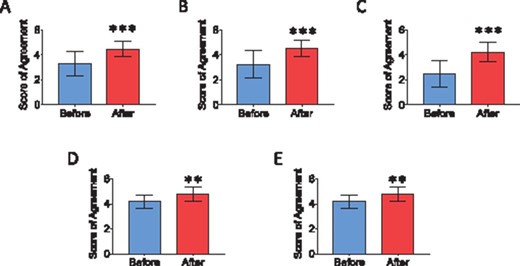

Based on 5-point Likert scale, where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree, students indicated a mean improvement (1.18±1.07) in understanding the definition of a clinical audit (p<0.001) (figure 2A). CAPS also improved the confidence of students to approach a supervisor to collaborate on a project (1.29±1.21, p<0.001) and conduct an audit by themselves in the future (1.77±1.15, p<0.001) (figure 2B, C). CAPS also enhanced to students the importance of conducting audits for their future career (0.58±0.51, p<0.01) and improving patients’ quality of care (0.41±0.51, p<0.01) (figure 2D, E). Of the eight students that completed their audit, six students presented their project results at regional and national meetings, and four of these secured an oral presentation within 9 months. It was noteworthy that one student won a national prize for their presentation.

Based on 5-point Likert scale, where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree, 17 student responses demonstrating their Likert score of agreement, before and after the programme, to (A) understanding definition of a clinical audit. (B) Confidence in approaching a supervisor to collaborate on a clinical audit. (C) Confidence in carrying out a clinical audit by themselves. (D) Understanding the importance of carrying out clinical audits to help their future career. (E) Understanding the importance of carrying out clinical audits to improve patients’ quality of care. * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 ***p<0.001.

Overall, though 50% of the students reported awareness of the programme among their year group, 90% of the students reported good organisation of the programme and all students (100%) stated they would recommend CAPS programme to their colleagues and encouraged the running of CAPS for successive years.

Supervisors

Five of the seven supervisors responded to the survey and four of them (80%) indicated that they had projects that remained inactive due to a lack of assistance. All supervisors were happy with the quality of work produced by their students and none found the role demanding. Further, all supervisors reported good organisation of the programme.

DISCUSSION

The importance of auditing and QI is well recognised and established as part of training and in some undergraduate curricula.5 Several organisations provide educational resources and training opportunities to explain the theory behind audits and QI.20 21 However, despite the numerous resources available, 58.8% of the students in our sample did not possess sufficient knowledge and 82.3% were not confident in carrying out an audit. CAPS proved to successfully improve students’ knowledge of undertaking clinical audits and subsequently aided students in approaching clinicians, by acting as a bridge between them. This was vital for younger students who lack confidence in approaching supervisors themselves. Furthermore, it gave students confidence in conducting audit projects and helped to reduce the current burden on centres to provide consistent QI projects and help towards better care of patients.

Clinical audits, while invaluable in their own right, act as a stepping-stone to a wide range of opportunities. Completion of audit projects and subsequent dissemination at local, regional or national meetings further strengthen students’ Curriculum Vitae (CV). Audits carry a significant weighting on Core Surgical Training (CST) and other higher speciality training programme applications, given their importance in bettering clinical practice.22 23 Successful completion of clinical audits and QI projects is one of the highest scoring categories on the 2020 CST portfolio (11 out the total 72 points available).24 Only 37.7% of junior doctors continue straight to speciality training,25 with the remaining unable to, often due to the lack of a strong portfolio.26 Thus, several doctors take a Foundation Year 3 to strengthen their application,26 while others often find themselves waiting years before their portfolios are sufficiently strong for a successful outcome following interview.27 This is concerning considering the UK’s ever-increasing workforce pressures where competent trainees are required more than ever.28 More doctors may have been successful with stronger portfolios and the necessary opportunities to develop this. Further, as part of the portfolio, trainees also need to demonstrate ‘commitment to speciality’.24 Project Cutting Edge (PCE),29 a national organisation focused on supporting surgical career development, encourages ‘constant continuous improvement’30 from the beginning of their careers. Gundogan et al 27 identified that medical trainees’ career starts at the beginning of medical school rather than Foundation Year 1 (FY1), and thus career building should begin at medical school. As such, more medical students wishing to apply for competitive specialities, such as T&O, want to complete audits early on, to demonstrate this ‘commitment to speciality’ and strengthen their portfolio.24

Oral presentations score the highest number of points in the ‘presentations’ section of 2020 CST portfolio (6 out of a possible 72).24 Stewart et al 31 identified that most trainees struggle to obtain oral presentations. However, as a result of CAPS programme, four out of six students who presented their work secured an oral presentation within 9 months. Where students struggle to obtain necessary prizes to fulfil the ‘academic achievements’ of the CST portfolio,24 it was noteworthy that one student won a national prize for their presentation and would have scored the maximum points in the ‘academic achievements’ section (an additional 5 points out of 72).

Clinical audits also often act as gateways into clinical academia.32 Participation in CAPS offers a practical opportunity for students to explore the application of evidence-based medicine.12 Throughout the process of completing their project, students gain transferable skills such as data collection and interpretation that may be used for larger research projects, enriching their skillset.33 Early exposure to CAPS may prompt interest in clinical academia,34 possibly addressing the current shortfall of the clinical academic faculty that we are faced with.35 Furthermore, in the light of the increasing importance of audits and subsequent sharing of results between trusts, there are now several journals such as Future Hospital Journal and BMJ Quality Improvement Reports that publish QI and audit projects to standardise and increase the dissemination of these previously underreported projects.5 With these increasing opportunities to publish audits, students could score an additional 6 points in the ‘Publications’ section of the CST portfolio. Students can successfully score 28 out of a total 72 points (39% of the points) with one single audit project, demonstrating the need for such a platform to help strengthen students’ CV and increase their chances of pursuing their chosen speciality.

STARSurg36 is a national multicentre collaborative audit and research network that helps medical student collaborators contribute data to clinical studies. Throughout this process, medical students are usually assigned a strict ‘data collection’ role within the collaboration. Our audit programme is considerably different to collaborative networks such as STARSurg, as the students in our audit platform are responsible for all stages of the audit process, from the formulation of specific aims and methodology creation, through to data analysis and dissemination. Students learn all aspects of the audit process with the platform focusing on engaging supervisors and students at a local level. While the participant numbers are expectedly not as high as STARSurg national collaborative studies, the local audits are much more likely to initiate interventions rapidly.

Many undergraduate medical students are unsure about their career intentions,37 with our programme highlighting that only 35.3% of the participants were interested in pursuing a career in T&O, at the start of the programme. Where the number progressing to higher surgical training has been decreasing annually over the last 8 years,25 studies highlight that 50% of surgical trainees experience burnout and 44% of trainees are with low morale.29 PCE states that a more sustainable form of training is required,29 with passion for the speciality directly translating into a more ‘constant, continuous’ and holistic effort.30 This will not only increase work ethic, but also combat burnout and guide future surgeons towards a happy and successful career in surgery.38–40 Our study also highlights how our programme provides a valuable insight into T&O for medical students, with 70.5% of the participants being inspired to pursue a career in T&O following the completion of the programme. For the remaining participants, the completion of an audit would be equally valuable, as audits, presentations and publications are weighted similarly across most training programmes.41

While all students (100%) reported they would recommend CAPS to their colleagues, 50% of the students reported limited awareness of CAPS in their year groups. Our study is limited to one region with a small size of 17 students and five supervisors. However, CAPS was a pilot study to assess feasibility and troubleshoot any issues. Increased advertisement for these opportunities at medical school, local trusts and social media is required to upscale the programme. This will not only allow more student involvement but will increase awareness among potential supervisors.

Though 90% of the students and all supervisors reported good organisation of the programme, both highlighted the need for an online database to reduce allocation inefficiencies. A database in which supervisors can post projects and request any number of medical students to join would aid in streamlining the process and afford instantaneous allocation on a larger scale. After ensuring that students interested in a particular subspeciality are matched with respective supervisors, and thereby reducing attrition rates, the database can track progress, issues that they may occur and offer support, to ensure successful audit completion.

Liimitations

Our study shows a high attrition rate throughout the programme, with only 19 students starting a project from the initial 30 who joined the platform. This was primarily due to the challenges of communication between the society and the participants. However, this limitation ensured that only students who were interested and motivated remained, with nearly 50% of them completing their projects within 6 months. Communication proved to be the biggest hurdle between the society and student members. Once students had received their supervisor and project allocation, there was a poor email response rate. Despite eight students indicating completion of their clinical audits in the feedback, only two audit proposal forms and one audit completion form were received. This was often due to the mandatory requirement of supervisors’ signatures, and so, the implementation of an online platform in the future will solve this problem. A possible strategy for improving student response rates would be awarding certificates upon successful completion of the programme as evidence in their portfolio and reminding students of this incentive via email.

CONCLUSION

Clinical audits are essential, not only to T&O, but all medical and surgical specialities in the context of QI for patient care. The CAPS programme produced successful audit projects that were disseminated locally, nationally and internationally, with positive feedback from both students and supervisors. Our aim is to continue to refine and upscale this programme, in order to provide the bridge between medical students and clinicians. In this particular example, the presence of a trainee collaborative allowed the CAPS programme to successfully and efficiently dovetail with the BON allowing a more synergistic and productive relationship. This sort of link organisation may also benefit clinical specialities in the current climate where recruitment is becoming increasingly challenging. We publish our pilot study findings to encourage similar audit programmes to be adopted at other universities and by other specialities, to further benefit medical students, clinicians and ultimately patients on a larger scale.

Doctors are required to complete regular clinical audits as part of the General Medical Council’s ‘Good Medical Practice’ guidance yet struggle to do so.

Despite strong motivations to participate in audit projects, many students do not complete them before graduating due to various barriers.

Previous attempts at developing student-clinician collaboration projects have usually restricted students to solely a data collector role.

Medical students are not confident in approaching supervisors to get involved with an audit project.

Physicians have outstanding or neglected audit projects that are not pursued due to a lack of time and resources.

Engaging with a project can improve a medical student’s confidence, knowledge and ability to conduct future audit.

What are the barrier and facilitators to engaging with audits as a medical student?

How can developmental programmes improve communications with student participants?

What is the demand for similar audit platforms from medical students across the UK?

Acknowledgements

We would like to that all the participants who have completed the questionnaire and the Birmingham Orthopaedic Network who made this possible.

Footnotes

All three authors participated equally in the research of this paper, assisting in all of the following parts: guarantor of integrity of the entire study: PRK, YH, RM and VD. Study concepts and design: PRK, YH and RM. Literature research: PRK, YH and RM. Clinical studies: PRK, YH and RM. Experimental studies/data analysis: PRK, YH and RM. Statistical analysis: PRK, YH and RM. Manuscript preparation: PRK, YH, RM and VD. Manuscript editing: PRK, YH, RM and VD. Manuscript revision: PRK, YH, RM and VD.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. All author information provided in the conflict of interest forms is current.

Not required.

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data are available upon reasonable request.