-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jizhao Niu, Bai Li, Qing Zhang, Ge Chen, Angeliki Papadaki, Exploring the traditional Chinese diet and its association with health status—a systematic review, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 83, Issue 2, February 2025, Pages e237–e256, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuae013

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Increased adherence to a traditional Chinese diet (TCD) could reduce the increasing prevalence of noncommunicable diseases. Currently, there is no consistent definition of the TCD in the literature, and its associations with health outcomes have not yet been identified.

This systematic review aimed to assess the definition of the TCD, in the literature, and to evaluate whether the TCD, as described, is associated with health outcomes.

Fourteen databases were searched up to April 25, 2022.

Three reviewers (in pairs) independently screened and extracted data. A modified risk-of-bias tool was used to assess the quality of the studies assessing the TCD definition; the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale and the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool were used to assess the quality of the observational studies and randomized controlled trials assessing associations between the TCD and health outcomes.

Ninety-nine studies were identified that assessed the TCD definition. In at least 75% of the studies, rice and leafy vegetables were consistently reported as food groups that characterize the TCD; the most frequently cited food items were white rice, spinach, bokchoy, and cabbage. Fish and seafood, pork, and pork products were consistently reported in studies exclusively referring to the TCD consumed in southern China (n = 21 studies), whereas wheat and wheat products were commonly reported in studies focusing on northern China (n = 14 studies). Fifteen studies reported on the quantities of food groups that are characteristic of the TCD, but their findings were inconsistent. Of the 99 studies, 54 assessed associations with health outcomes. The TCD was overall inversely associated with obesity risk and weight gain, while relationships between the TCD and other health outcomes were inconsistent.

Further studies are needed to determine the quantities of foods consumed in the TCD and to establish a consistent definition for further exploration of the TCD’s potential role in preventing non-communicable diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes, have major implications on a global scale.1,2 In the past decade, approximately 41 million people died from NCDs each year, accounting for 71% of all global deaths.3 Additionally, global data from 2016 indicate that NCDs were responsible for 61.4% of disability-adjusted life years.4 It has been suggested that China contributes the largest number of patients and deaths related to NCDs,5 and NCDs have become the biggest health challenge to China, accounting for 89% of its 9.98 million annual deaths.6 A World Bank report estimated that morbidity and mortality attributable to NCDs are expected to rise by approximately 50% and 80%, respectively, in China, by 2030.7

Poor diet is globally regarded as a primary risk factor for NCDs.8 To reduce the increasing prevalence of NCDs, traditional dietary patterns have been recommended by several international organizations.9,10 These diets are commonly regarded as healthy, because they include a large amount of plant-based foods, such as vegetables, fruits and grains, as well as a small amount of foods of animal origin and oils.11,12 For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials has indicated that the Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced risk of a multitude of NCDs, such as CVDs, stroke, and breast cancer,13 so it should be promoted as a healthy dietary pattern. However, due to cultural and geographical influences, it may not be feasible to promote the Mediterranean diet in all countries.

China has undergone major socio-economic transitions over the past decades, in parallel with important transitions in food supply and dietary habits.14 The Chinese diet is being gradually Westernized, with a reduction in the consumption of vegetables and whole grains, and an increase in the intake of refined grains, red meat, and unhealthy fats, which has been suggested to have contributed to the increasing prevalence of NCDs in the country.15 Therefore, promoting the TCD might be an important public health measure for addressing the high rates of NCDs in China.16 However, there are various definitions of the TCD in the existing literature, potentially due to the diverse eating habits and cultural traditions across Chinese regions, and the significant changes to food habits and food culture over time.17,18 These diverse definitions make it challenging to establish the association between the TCD and health outcomes.18 Currently, no consistent definition of the TCD has been achieved. Additionally, no study has systematically evaluated the definition of the TCD and its association with health outcomes in the existing literature.

The aim of this study was, therefore, to systematically assess how the TCD is defined in the existing literature, and to evaluate the association between the TCD, as defined in the literature, with health outcomes. The specific objectives were: (1) to identify the food groups and food items that were consistently identified as components of the TCD, as well as the frequency of consumption and amount consumed; and (2) to synthesize and appraise the published evidence on the association between the TCD and health outcomes.

METHODS

This review was conducted based on a registered protocol (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42022321637), and reported following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Supplementary Materials I, see Table S1 in the Supporting Information online).19

Search strategy

Searches were performed to identify peer-reviewed articles, books, and gray literature (such as conference abstracts, and reports) published in English and/or Chinese, up to April 25, 2022, without any limitations in terms of the publication date or place. Local chronicles (like Di Fang Zhi) were not considered eligible for inclusion, because they focus more on the history of a single food, not the whole diet. Databases searched were Anthropology Plus, PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, ProQuest (Dissertations and Theses), PsycINFO, Scopus, CENTRAL and Cochrane Reviews, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Data, VP Website, and SinoMed (CBM). The search strategy was designed by J.N., with consultation with B.L. and A.P., and tailored to each database; the detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary Materials I; see Table S2 in the Supporting Information online.

Study eligibility criteria

This systematic review applied PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design)20 criteria for each research question, as detailed in Table 1. Studies and articles describing diet as “traditional” Chinese were considered eligible, including those conducted outside of China, as long as they referred to diets distinctive of China. Articles that discussed a specific geographical area of China and those focused on the traditional diet of a minority group were included as well. Studies and articles were excluded if: (1) they only focused on single foods or nutrients instead of the whole dietary pattern; (2) they did not identify a “traditional” diet; and (3) they were duplicate studies (such as articles by different authors containing information on the same study or project).

| Parameter . | Inclusion criteria for the first research question (assessment of the TCD definition) . | Inclusion criteria for the second research question (assessment of associations between the TCD and health outcomes) . |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults aged over 18 years who consume a traditional Chinese diet, except postpartum women, especially those breastfeeding | Same as research question 1 |

| Intervention/exposure | NA | Dietary pattern labelled as TCD and/or eating habits recognized as traditional Chinese, and/or highest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Comparison/control | NA | Other types of dietary patterns; no treatment or usual care in terms of diet; lowest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Outcome | Definition of the traditional Chinese diet | Overall incidence or prevalence of NCDs (such as diabetes, cancer, etc.); metabolic risk factors; BMI and other related factors (such as waist circumference); diabetes risk factors (such as blood concentrations of glucose); other NCD-related outcomes |

| Study design | All types of studies | Quantitative peer-reviewed studies |

| Parameter . | Inclusion criteria for the first research question (assessment of the TCD definition) . | Inclusion criteria for the second research question (assessment of associations between the TCD and health outcomes) . |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults aged over 18 years who consume a traditional Chinese diet, except postpartum women, especially those breastfeeding | Same as research question 1 |

| Intervention/exposure | NA | Dietary pattern labelled as TCD and/or eating habits recognized as traditional Chinese, and/or highest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Comparison/control | NA | Other types of dietary patterns; no treatment or usual care in terms of diet; lowest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Outcome | Definition of the traditional Chinese diet | Overall incidence or prevalence of NCDs (such as diabetes, cancer, etc.); metabolic risk factors; BMI and other related factors (such as waist circumference); diabetes risk factors (such as blood concentrations of glucose); other NCD-related outcomes |

| Study design | All types of studies | Quantitative peer-reviewed studies |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable; NCDs, noncommunicable diseases; TCD, Traditional Chinese diet.

| Parameter . | Inclusion criteria for the first research question (assessment of the TCD definition) . | Inclusion criteria for the second research question (assessment of associations between the TCD and health outcomes) . |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults aged over 18 years who consume a traditional Chinese diet, except postpartum women, especially those breastfeeding | Same as research question 1 |

| Intervention/exposure | NA | Dietary pattern labelled as TCD and/or eating habits recognized as traditional Chinese, and/or highest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Comparison/control | NA | Other types of dietary patterns; no treatment or usual care in terms of diet; lowest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Outcome | Definition of the traditional Chinese diet | Overall incidence or prevalence of NCDs (such as diabetes, cancer, etc.); metabolic risk factors; BMI and other related factors (such as waist circumference); diabetes risk factors (such as blood concentrations of glucose); other NCD-related outcomes |

| Study design | All types of studies | Quantitative peer-reviewed studies |

| Parameter . | Inclusion criteria for the first research question (assessment of the TCD definition) . | Inclusion criteria for the second research question (assessment of associations between the TCD and health outcomes) . |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults aged over 18 years who consume a traditional Chinese diet, except postpartum women, especially those breastfeeding | Same as research question 1 |

| Intervention/exposure | NA | Dietary pattern labelled as TCD and/or eating habits recognized as traditional Chinese, and/or highest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Comparison/control | NA | Other types of dietary patterns; no treatment or usual care in terms of diet; lowest level of adherence to the TCD |

| Outcome | Definition of the traditional Chinese diet | Overall incidence or prevalence of NCDs (such as diabetes, cancer, etc.); metabolic risk factors; BMI and other related factors (such as waist circumference); diabetes risk factors (such as blood concentrations of glucose); other NCD-related outcomes |

| Study design | All types of studies | Quantitative peer-reviewed studies |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable; NCDs, noncommunicable diseases; TCD, Traditional Chinese diet.

Study selection

Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) was used for screening the search results. After eliminating the duplicates, the titles and abstracts of identified records were screened by 2 independent reviewers (J.N. and Q.Z.), followed by an independent review of the full texts against the eligibility criteria. Any discrepancy was solved by discussion (inter-rater reliability: Kappa = 0.74; 97% agreement). Consensus was achieved by consulting a third reviewer (A.P. and/or B.L.) if initial agreement could not be achieved.

Data extraction

First, 2 independent reviewers (J.N. and Q.Z.) conducted a pilot study of the data extraction form (Supplementary Materials I, see Table S3 in the Supporting Information online) with 10% of the studies. Following the pilot, these reviewers proceeded to extract data from the remaining studies. The extracted data included study characteristics (eg, author, country, publication date, and study area), methodological information (eg, study design and study aim), the characteristics of the population (eg, numbers, age, sex, and health status if applicable), the dietary pattern assessment method, and the definition and description of the diet. For the second objective, the intervention/exposure characteristics and descriptions of comparators/controls, outcome measures, quantitative outcomes (such as risk ratios [RRs], odds ratios [ORs], mean value, and prevalence rate), and covariates were also extracted. Any disagreement was resolved by discussions (inter-rater reliability: Kappa = 0.51; 96% agreement); consensus was achieved by consulting a third reviewer (A.P. and/or B.L.) if needed.

Data analysis for the definition of TCD (review question 1)

The frequency of the citation of food items and food groups was calculated for defining the TCD. All foods and food groups characterizing the TCD were extracted into an Excel document (see Supplementary Materials II in the Supporting Information online) to calculate the frequency of the citation of food items and food groups. Food items reported using different names were categorized into the same food group (for example, corn and maize were categorized into the corn and corn products group). If a study mentioned several food items belonging to one food group, each food item was calculated once and the food group was also only calculated under one citation. For example, if a source reported apples, pears and peaches, each was documented under one citation and the food group “fruits” was only calculated once, not 3 times, under that same citation. The categorization of food groups was based on a food grouping system developed specifically for the Chinese Health Nutrition Survey by researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Chinese Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety (INFS)21 (which separates foods into nutritionally and behaviorally meaningful food groups), and the Chinese Food Composition Tables (Supplementary Materials I, see Table S4 in the Supporting Information online).22

Methods used for defining geographical regions when calculating the food citation frequency

Different definitions of the TCD in the existing literature were presented by regions, such as the identified “traditional southern diet” and “traditional northern diet”. These used the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line (which has been widely recognized as an important north–south geographical demarcation line23) to divide China into northern and southern, in terms of the considerable differences that exist in natural geography, geology, and culture between the northern and southern regions.24,25 In this review, definitions based on this classification were subsequently defined as TCD, traditional southern diet, traditional northern diet, and traditional diet in minority groups. The food citation frequency was calculated and then reported by region (4 subgroups in total). If one study reported more than one regional dietary pattern, the frequency of food items and food groups in each diet were calculated separately.

However, China is a large country, and the differences in diets might not be limited to southern and northern. It was, therefore, deemed appropriate to use an additional classification method in addition to the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line, to better capture potential differences between regions and across geographical classification systems. The second approach, named “5-regions classification,” involved dividing China into 5 main areas in terms of dietary preferences and geographical characteristics: northern China, southern China, eastern China, western China, and central China.22 The primary reviewer (J.N.) recategorized the definitions into these 5 groups according to where the participants in the included studies came from, or the regions where the studies were conducted. Additionally, data from studies in which participants represented the whole country (ie, could not be classified as being from a single region) were categorized into the TCD group. The food citation frequency based on the recategorized regions (6 subgroups in total) was then calculated and reported.

Data analysis for associations between TCD and health outcomes (review question 2)

There was significant heterogeneity in the methods, populations, and outcomes used in studies considered eligible to address the second research question, so a narrative synthesis was a more appropriate method for reporting the findings than a meta-analysis.

Risk of bias, study quality, and quality of reporting

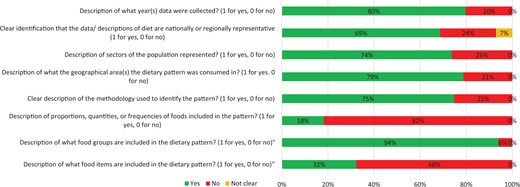

Considering the nature of the studies included in this systematic review for the first research question, the existing tools for assessing risk of bias were not deemed appropriate. Thus, the quality of these studies was assessed using an adapted tool that had previously been used in similar studies in India and Mexico.12,26 This 8-item index assessed whether the studies described: (1) the foods included in the dietary pattern; (2) the food groups included in the dietary pattern; (3) the proportions of the foods and food groups included; (4) the methodology used to identify the dietary pattern; (5) the geographical area(s) the dietary pattern was consumed in; (6) the population represented; (7) the identification of whether the data and descriptions of diet were nationally or regionally representative; and (8) the year(s) represented.

For studies assessing the association between the TCD and health outcomes, risk of bias was evaluated using an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cohort, cross-sectional, and case–control studies27,28 (Supplementary Materials I, see Table S5 in the Supporting Information online), while the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used for randomized controlled trials (RCTs).29 The overall quality of the reporting of cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies was also evaluated (by J.N.) using the STROBE statement,30 while the quality of reporting of RCTs was assessed via the CONSORT statement.31 Three independent reviewers (J.N., Q.Z., and G.C.) assessed risk of bias and discussed discrepancies until agreement was reached.

RESULTS

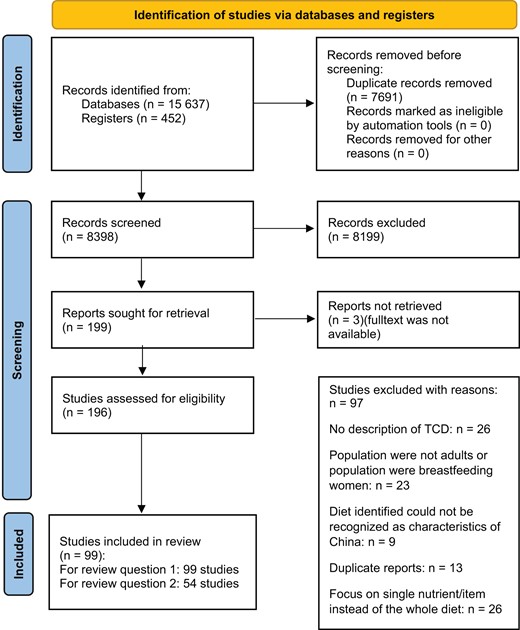

After removing the duplicates, 8398 articles remained for title and abstract screening, of which 8199 were excluded, as they were irrelevant to the review’s aim. As full texts could not be found for 3, the full text of a total of 196 studies was read, and 97 further studies were excluded (see detailed reasons in Supplementary Materials I [Table S6] in the Supporting Information online). Ultimately, a total of 99 studies were included, with all 99 reporting on the definition of the TCD and 54 evaluating the association between the TCD and health outcomes (Figure 1).

Definition of the TCD (research question 1)

Study characteristics

Among the 99 studies, 7 were editorials,32–38 8 were literature reviews14,39–45 and 84 were original research studies16,24,46–126 (Supplementary Materials I, see Table S7 in the Supporting Information online). Editorials largely described the TCD based on the authors’ experiences and understandings (eg, Zhao and Bao45 described foods and analyzed the characteristics of the TCD, according to their working experience in clinical nutrition). Most descriptions of the TCD (n = 84) focused on the period post the 1990s. Three reports, respectively, discussed the TCD between the early 1960s to and late 1970s,14 in the early 13th century,42 and in the period of the feudal dynasties.44 In the 8 literature reviews,14,39–45 historical and ethnographic data were utilized to described the TCD. The historical data were mostly drawn from manuscripts and chapters in books, and consisted of descriptions of foods consumed in the TCD during various periods. The ethnographic data included direct observations of the TCD among specific populations. All the original studies (n = 84) used quantitative methods to provide a definition of the TCD, including 18 cohort studies,46–63 58 cross-sectional studies,24,64–120 6 case–control studies,16,121–125 and 2 RCTs.126,127 Most included studies (n = 80) applied principal component analysis (PCA) or factor analysis (FA) to derive the TCD.

Definitions of the TCD in all studies

Among the included studies, only 35 listed food items that characterize the TCD. The food items that appeared in at least 75% of the studies were: white rice, spinach, bokchoy, and cabbage (Table 2a and see Supplementary Materials II in the Supporting Information online). All included studies (N = 99) listed the food groups that characterize the TCD. Food groups that were reported in at least 75% of the studies were rice and leafy fresh vegetables (Table 2b, and see Supplementary Materials II in the Supporting Information online). The food items and food groups also reported in at least 50% and 25% of studies are listed in Table 2a and b (see Supplementary Materials II in the Supporting Information online). Food items that appeared in at least 50% of the studies included fruits (eg, apples, pears). However, fruit was not reported as a food group characteristic of the TCD by at least 50% of studies, which might be due to the incomparability of percentages between food items and food groups. In some studies, special foods consumed by minority groups were also mentioned, such as köröngge (the top layer of cream made by boiling cow’s or sheep’s milk until a thin layer forms on the surface) in the Mongolian diet, and Dingguan (rice with mixed vegetables and meat) in the Tujia (one of the ethnic groups in China) diet (detailed explanations of special foods are shown in Supplementary Materials I, see Table S8 in the Supporting Information online).

| a. Food items listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 35) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . | Minority groups’ special foodsb . |

| White rice, spinach, bokchoy, cabbage | Brown rice, noodles, corn, millet, maize, porridge, rape, lettuce, celery, tomato, cucumber, carrot, white melon, onion, broccoli, pepper, apple, pear, etc.a, pork, freshwater fish, shellfish | Flour, steamed buns, oats, wheat, buckwheat, soup thickened with flour, beef, lamb, large intestine, chicken, duck, goose, smoked meat, dried fish, eggs, pickled vegetables, preserved salty vegetables, dried vegetables, tofu, beans, almonds, sweet potato, potato, taro | Kumis, köröngge, fermented mare’s milk, fried wheat, roasted horse meat, Ci, Zong, Dinggang, Gary tofu, oil tea, rice and wheat alcohol, braised pork belly, snake |

| a. Food items listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 35) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . | Minority groups’ special foodsb . |

| White rice, spinach, bokchoy, cabbage | Brown rice, noodles, corn, millet, maize, porridge, rape, lettuce, celery, tomato, cucumber, carrot, white melon, onion, broccoli, pepper, apple, pear, etc.a, pork, freshwater fish, shellfish | Flour, steamed buns, oats, wheat, buckwheat, soup thickened with flour, beef, lamb, large intestine, chicken, duck, goose, smoked meat, dried fish, eggs, pickled vegetables, preserved salty vegetables, dried vegetables, tofu, beans, almonds, sweet potato, potato, taro | Kumis, köröngge, fermented mare’s milk, fried wheat, roasted horse meat, Ci, Zong, Dinggang, Gary tofu, oil tea, rice and wheat alcohol, braised pork belly, snake |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 99) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 99) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

Including apple, pear, orange, peach, banana, grapes, cherries, jujube, apricots, cantaloupe, watermelon, grapefruit, kiwi, strawberries.

Detailed description of these foods can be found in the Supplementary Materials I, see Table S8 in the Supporting Information online.

| a. Food items listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 35) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . | Minority groups’ special foodsb . |

| White rice, spinach, bokchoy, cabbage | Brown rice, noodles, corn, millet, maize, porridge, rape, lettuce, celery, tomato, cucumber, carrot, white melon, onion, broccoli, pepper, apple, pear, etc.a, pork, freshwater fish, shellfish | Flour, steamed buns, oats, wheat, buckwheat, soup thickened with flour, beef, lamb, large intestine, chicken, duck, goose, smoked meat, dried fish, eggs, pickled vegetables, preserved salty vegetables, dried vegetables, tofu, beans, almonds, sweet potato, potato, taro | Kumis, köröngge, fermented mare’s milk, fried wheat, roasted horse meat, Ci, Zong, Dinggang, Gary tofu, oil tea, rice and wheat alcohol, braised pork belly, snake |

| a. Food items listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 35) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . | Minority groups’ special foodsb . |

| White rice, spinach, bokchoy, cabbage | Brown rice, noodles, corn, millet, maize, porridge, rape, lettuce, celery, tomato, cucumber, carrot, white melon, onion, broccoli, pepper, apple, pear, etc.a, pork, freshwater fish, shellfish | Flour, steamed buns, oats, wheat, buckwheat, soup thickened with flour, beef, lamb, large intestine, chicken, duck, goose, smoked meat, dried fish, eggs, pickled vegetables, preserved salty vegetables, dried vegetables, tofu, beans, almonds, sweet potato, potato, taro | Kumis, köröngge, fermented mare’s milk, fried wheat, roasted horse meat, Ci, Zong, Dinggang, Gary tofu, oil tea, rice and wheat alcohol, braised pork belly, snake |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 99) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies (n = 99) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

Including apple, pear, orange, peach, banana, grapes, cherries, jujube, apricots, cantaloupe, watermelon, grapefruit, kiwi, strawberries.

Detailed description of these foods can be found in the Supplementary Materials I, see Table S8 in the Supporting Information online.

Definitions of the TCD according to two different methods of defining regions

Definitions of TCD according to the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line

As mentioned above, since only 35 studies reported food items, all subsequent analyses were conducted based on food groups, rather than individual food items. There were 4 main regions reported in the literature: all regions (n = 69, representing the TCD),14,16,32–39,43–45,49–54,56–60,64–67,71,72,74,77–82,86,88,90,93,95,96,98,100–103,105–108,111–121,123–128southern China (n = 21, representing the traditional southern diet),14,24,40,46–48,63,69,70,83–85,87,89,92,94,99,104,109,110,122 northern China (n = 14, representing the traditional northern diet),24,40,46,55,61,62,69,73,76,91,92,94,97,109 and minority groups (n = 3).41,42,75 Eight studies focused on more than one area of China.24,40,46,69,92,94,97,109

The studies referring to all regions (n = 69) reported similar food groups to the overall definitions identified in “Definitions of the TCD in All Studies” (Table 3a). Most of the studies (n = 52) listed rice and leafy fresh vegetables, and more than 50% of them (n = 35) reported wheat and wheat products. Pork and pork products and fish and seafoods were also reported by nearly 50% of the studies (n = 31). The studies referring exclusively to southern China (n = 21) showed some differences in food groups with at least 75% citations, compared with the descriptions of traditional northern diet. Fish and seafoods were mentioned more frequently (in 75% of the studies). They also included calorically sweetened beverages and ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, which were not mentioned in other areas (Table 3b). Studies referring exclusively to northern China (n = 14) reported food groups that differed from those in the studies of all regions. Most of these studies (75%, n = 11) mentioned wheat and wheat products, as well as wheat with a filling, which was different from the southern diet. Moreover, corn and coarse grains were mentioned (50%, n = 6), which was not the case for the southern diet. However, fish and seafoods, as well as legume products, were mentioned less frequently (Table 3c).

Most-cited food groups reported in the included studies, by region (according to the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line)

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions(n = 69) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits; pork and pork products, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions(n = 69) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits; pork and pork products, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China(n = 21) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Fish and seafood, leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Nonleafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, poultry and game, legume products, dried legumes | Animal-based milk, beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, eggs and egg products, fruits, instant food, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, processed meat, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China(n = 21) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Fish and seafood, leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Nonleafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, poultry and game, legume products, dried legumes | Animal-based milk, beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, eggs and egg products, fruits, instant food, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, processed meat, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| c. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China(n = 14) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling | Corn and coarse grain, leafy fresh vegetables | Beef and beef products, dairy products, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, rice, starchy roots and tubers, starchy root products and tuber products |

| c. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China(n = 14) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling | Corn and coarse grain, leafy fresh vegetables | Beef and beef products, dairy products, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, rice, starchy roots and tubers, starchy root products and tuber products |

| d. Food groups listed in minority groups (Hakka: n = 1, Tujia: n = 1, Mongolian: n = 1) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hakka . | Tujia . | Mongolian . |

| Dried legumes, fish and seafood, fruits, organ meat, rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Calorically sweetened beverages, corn and coarse grain, legume products, starchy roots and tubers, rice, leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products | Beef and beef products, dairy products, lamb and lamb products, oil, other livestock, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| d. Food groups listed in minority groups (Hakka: n = 1, Tujia: n = 1, Mongolian: n = 1) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hakka . | Tujia . | Mongolian . |

| Dried legumes, fish and seafood, fruits, organ meat, rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Calorically sweetened beverages, corn and coarse grain, legume products, starchy roots and tubers, rice, leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products | Beef and beef products, dairy products, lamb and lamb products, oil, other livestock, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

Most-cited food groups reported in the included studies, by region (according to the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line)

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions(n = 69) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits; pork and pork products, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions(n = 69) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits; pork and pork products, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China(n = 21) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Fish and seafood, leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Nonleafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, poultry and game, legume products, dried legumes | Animal-based milk, beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, eggs and egg products, fruits, instant food, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, processed meat, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China(n = 21) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Fish and seafood, leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Nonleafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, poultry and game, legume products, dried legumes | Animal-based milk, beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, eggs and egg products, fruits, instant food, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, processed meat, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| c. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China(n = 14) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling | Corn and coarse grain, leafy fresh vegetables | Beef and beef products, dairy products, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, rice, starchy roots and tubers, starchy root products and tuber products |

| c. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China(n = 14) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling | Corn and coarse grain, leafy fresh vegetables | Beef and beef products, dairy products, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, rice, starchy roots and tubers, starchy root products and tuber products |

| d. Food groups listed in minority groups (Hakka: n = 1, Tujia: n = 1, Mongolian: n = 1) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hakka . | Tujia . | Mongolian . |

| Dried legumes, fish and seafood, fruits, organ meat, rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Calorically sweetened beverages, corn and coarse grain, legume products, starchy roots and tubers, rice, leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products | Beef and beef products, dairy products, lamb and lamb products, oil, other livestock, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| d. Food groups listed in minority groups (Hakka: n = 1, Tujia: n = 1, Mongolian: n = 1) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hakka . | Tujia . | Mongolian . |

| Dried legumes, fish and seafood, fruits, organ meat, rice, leafy fresh vegetables | Calorically sweetened beverages, corn and coarse grain, legume products, starchy roots and tubers, rice, leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products | Beef and beef products, dairy products, lamb and lamb products, oil, other livestock, pork and pork products, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

China has 56 ethnic groups; each has its own unique cultural and culinary traditions.129 Three studies discussed the diet in minority ethnic regions (Hakka: n = 175; Tujia: n = 141; Mongolia: n = 142). Using the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line to define the regions, Hakka and Tujia are mostly located in southern China, and Mongolia is clustered in northern China. Consumption of dried legumes and organ meats was reported as a more common characteristic of the Hakka diet compared with other minority groups’ diets; Mongolians seemed to consume red meat (including beef, lamb, and other livestock) and oil more frequently. Rice was reported in the Hakka and Tujia diets, which was similar to other studies referring to southern China14,24,40,46–48,63,69,70,83–85,87,89,92,94,99,104,109,110,122; wheat and wheat products and wheat with a filling were also reported to be characteristic of the Mongolian diet, as in other studies conducted in northern China (Table 3d).24,40,46,55,61,62,69,73,76,91,92,94,97,109

Definitions of TCD according to the 5-regions method

There were 6 regions represented after applying the 5-region classification method: all regions (n = 39,24,32–35,37–40,43–49,53–56,59–63,65,69,85,87,92,94,101–103,109,110,126,127,130 representing the TCD), southern China (n = 7,36,50,51,77,111,113,120 representing the traditional southern diet), northern China (n = 15,42,71,73,74,76,79,91,95–97,100,105,106,108,128 representing the traditional northern diet), eastern China (n = 35),14,16,52,57,58,64,66,67,70,75,78,80–84,86,88–90,93,98,99,104,107,114–116,118,119,121–125 representing the traditional eastern diet, western China (n = 1),117 and central China (n = 2,41,72 representing the traditional central diet).

The most cited food groups in the TCD were leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, and rice (Table 4a), which is similar to the findings produced using the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line method. Studies referring to eastern China (n = 35), northern China (n = 15), and central China (n = 2) showed similarities in terms of leafy fresh vegetables. For staple foods, 75% of the studies from eastern (n = 29) and southern (n = 7) China mentioned rice to be characteristic of these diets, while those from northern (n = 10) China reported wheat and wheat products, with corn and coarse grains also being frequently mentioned in relation to central China (n = 2). Legume products were mentioned more frequently in southern China than in other regions. Only one article related to the western Chinese region was available,117 so it was not included in the food citation frequency statistics, but the food groups mentioned in the article were listed (Table 4c).

Most-cited food groups present in the included studies, by region (according to the 5-regions method)

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions (n = 39) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, rice | Fish and seafood, poultry and game, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, dried legumes, nonleafy fresh vegetables, legume products, organ meats, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions (n = 39) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, rice | Fish and seafood, poultry and game, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, dried legumes, nonleafy fresh vegetables, legume products, organ meats, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to eastern China (n = 35) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Fish and seafood, wheat and wheat products | Corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, starchy roots and tubers |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to eastern China (n = 35) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Fish and seafood, wheat and wheat products | Corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, starchy roots and tubers |

| c. Food groups listed in western China (n = 1) . |

|---|

| Beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, deep-fried wheat, starchy roots and tubers, wheat and wheat products |

| c. Food groups listed in western China (n = 1) . |

|---|

| Beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, deep-fried wheat, starchy roots and tubers, wheat and wheat products |

| d. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China (n = 7) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice | Leafy fresh vegetables, legume products | Beef and beef products, fish and seafood, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, starchy roots products and tubers products, wheat and wheat products |

| d. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China (n = 7) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice | Leafy fresh vegetables, legume products | Beef and beef products, fish and seafood, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, starchy roots products and tubers products, wheat and wheat products |

| e. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China (n = 15) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, wheat and wheat products | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, rice | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grains, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, fungi and algae, legume products, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| e. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China (n = 15) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, wheat and wheat products | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, rice | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grains, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, fungi and algae, legume products, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| f. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to central China (n = 2) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Corn and coarse grains, leafy fresh vegetables, legume products, rice, wheat and wheat products | Calorically sweetened beverages, dairy products, eggs and egg products, pork and pork products, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, starchy roots and tubers | NA |

| f. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to central China (n = 2) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Corn and coarse grains, leafy fresh vegetables, legume products, rice, wheat and wheat products | Calorically sweetened beverages, dairy products, eggs and egg products, pork and pork products, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, starchy roots and tubers | NA |

Most-cited food groups present in the included studies, by region (according to the 5-regions method)

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions (n = 39) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, rice | Fish and seafood, poultry and game, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, dried legumes, nonleafy fresh vegetables, legume products, organ meats, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| a. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to all regions (n = 39) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, pork and pork products, rice | Fish and seafood, poultry and game, wheat and wheat products | Beef and beef products, dried legumes, nonleafy fresh vegetables, legume products, organ meats, wheat and wheat products, wheat with a filling |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to eastern China (n = 35) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Fish and seafood, wheat and wheat products | Corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, starchy roots and tubers |

| b. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to eastern China (n = 35) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, rice | Fish and seafood, wheat and wheat products | Corn and coarse grain, dried legumes, eggs and egg products, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, legume products, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, pork and pork products, starchy roots and tubers |

| c. Food groups listed in western China (n = 1) . |

|---|

| Beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, deep-fried wheat, starchy roots and tubers, wheat and wheat products |

| c. Food groups listed in western China (n = 1) . |

|---|

| Beef and beef products, calorically sweetened beverages, deep-fried wheat, starchy roots and tubers, wheat and wheat products |

| d. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China (n = 7) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice | Leafy fresh vegetables, legume products | Beef and beef products, fish and seafood, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, starchy roots products and tubers products, wheat and wheat products |

| d. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to southern China (n = 7) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Rice | Leafy fresh vegetables, legume products | Beef and beef products, fish and seafood, fruits, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, starchy roots products and tubers products, wheat and wheat products |

| e. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China (n = 15) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, wheat and wheat products | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, rice | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grains, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, fungi and algae, legume products, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| e. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to northern China (n = 15) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Leafy fresh vegetables, wheat and wheat products | Fish and seafood, pork and pork products, rice | Beef and beef products, corn and coarse grains, eggs and egg products, fish and seafood, nonleafy fresh vegetables, fruits, fungi and algae, legume products, oil, organ meats, pickled, salted or canned vegetables, poultry and game, starchy roots and tubers |

| f. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to central China (n = 2) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Corn and coarse grains, leafy fresh vegetables, legume products, rice, wheat and wheat products | Calorically sweetened beverages, dairy products, eggs and egg products, pork and pork products, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, starchy roots and tubers | NA |

| f. Food groups listed in at least 75%, 50%, and 25% of the studies referring to central China (n = 2) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% . | 50% . | 25% . |

| Corn and coarse grains, leafy fresh vegetables, legume products, rice, wheat and wheat products | Calorically sweetened beverages, dairy products, eggs and egg products, pork and pork products, ready-to-eat cereals and porridge, starchy roots and tubers | NA |

Food groups inversely associated with the TCD

A total of 42 studies, which used PCA in their analysis to derive the TCD, reported food groups that are inversely associated with the TCD.24,46–50,53–59,61–65,67,69,71,78–81,85–87,94,101–103,109,111,113,118,122–124,130 These food groups (Table 5) were, therefore, considered not to be characteristic of the TCD. Wheat and wheat products were mostly reported to be negatively associated with the TCD (n = 19). Moreover, 25% of these studies also mentioned an inverse association between Western-style fried and fast foods, starchy roots and tubers, and rice, and the TCD.

Most-cited food groups that were inversely associated with a traditional Chinese diet

| Food groups listed with inverse associations in at least 50%, 25%, and 10% of the studies (n = 42) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 50% . | 25% . | 10% . |

| Wheat and wheat products | Western-style fried and fast foods, starchy roots and tubers, rice | Corn and coarse grains, deep-fried wheat, dried legumes, fish and seafood, pork and pork products, poultry and game |

| Food groups listed with inverse associations in at least 50%, 25%, and 10% of the studies (n = 42) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 50% . | 25% . | 10% . |

| Wheat and wheat products | Western-style fried and fast foods, starchy roots and tubers, rice | Corn and coarse grains, deep-fried wheat, dried legumes, fish and seafood, pork and pork products, poultry and game |

Most-cited food groups that were inversely associated with a traditional Chinese diet

| Food groups listed with inverse associations in at least 50%, 25%, and 10% of the studies (n = 42) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 50% . | 25% . | 10% . |

| Wheat and wheat products | Western-style fried and fast foods, starchy roots and tubers, rice | Corn and coarse grains, deep-fried wheat, dried legumes, fish and seafood, pork and pork products, poultry and game |

| Food groups listed with inverse associations in at least 50%, 25%, and 10% of the studies (n = 42) . | ||

|---|---|---|

| 50% . | 25% . | 10% . |

| Wheat and wheat products | Western-style fried and fast foods, starchy roots and tubers, rice | Corn and coarse grains, deep-fried wheat, dried legumes, fish and seafood, pork and pork products, poultry and game |

Quantities of food consumption in the TCD

A total of 15 studies reported the amounts of food groups that were consumed in the TCD,16,54,55,57,72,86,88,93,101,104,116,121,123,126,127 while only 3 of them reported the quantities of food items.88,104,127 Hence, this review focused on the analysis of food groups, due to the limited number of studies reporting on the quantities of specific food items. One study assessed the percentage of energy distribution by food groups16; 5 reported the average quantities of foods consumed daily or weekly54,72,93,121,126; 8 studies reported the consumed food groups by quartiles/quintiles of intake.55,57,86,88,101,104,116,123 One study provided detailed accounts of food consumption, but was not considered in this section.127 This was due to its focus solely on describing food items presented in a recipe as an intervention, without providing any recommendations regarding the quantities of these foods typically consumed in the TCD.

The reported quantities of food groups consumed are shown in Supplementary Materials I (see Table S9 in the Supporting Information online). It was not possible to reach an agreement on the quantities of the food groups consumed in the TCD, because the studies applied different methods for assessing food groups and reported different amounts. For example, even in the studies that used the same method for assessing the quantity of fresh vegetables consumed in the TCD, the results varied from 279.1 g (standard deviation, SD 179)54 to 500 g (SD 131)72 per day. This wide variation was also observed for other food groups, such as fruits and eggs. Additionally, these studies grouped foods differently. For instance, some studies combined different kinds of meat together, referring to them as “meat,” while others separated meat into livestock and poultry.72 Likewise, the quantities of some food groups, such as soft drinks,121 and wheat and wheat products,86 were not comparable between studies as they were only reported in some of the studies. These differences limited our ability to obtain a consensus on the quantities of the food groups consumed in the TCD.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Most studies clearly reported 75% of the indicators for the risk-of-bias assessment (Supplementary Materials I [see Table S10 in the Supporting Information online]). However, fewer studies described the quantities of foods/food groups (n = 15) and included descriptions of food items (n = 35) (Figure 2).

Associations between the TCD and health outcomes (research question 2)

Study characteristics

Among the 99 studies that defined the TCD in the current review, 54 also assessed associations between the reported TCD and NCD-related health outcomes (Supplementary Materials I [see Table S11 in the Supporting Information online]). One study was an RCT,127 4 were case–control studies,16,121–123 12 were cohort studies,47,49,51–53,55–60,62 and 37 were cross-sectional studies.24,64–66,69,71,72,74–76,78,82–89,91,92,94,95,97–101,103,104,107,109–111,114,116,118 All studies used a validated food frequency questionnaire to collect dietary information, and most of them (n = 52) used FA/PCA to derive the TCD. One case–control study applied latent class analysis to assess the diet, as this allowed the identification of unobserved subgroups or classes within cases.121 One study reported the daily consumption of foods to show the composition of the TCD.127

Cancer

Two case–control studies evaluated the association between the TCD and risk of breast cancer, with one showing null findings (OR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.65–1.14)121 and the other indicating an inverse association, for both menopausal (OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.48–0.97) and pre-menopausal women (OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.29–0.76).123 One study also explored the traditional Cantonese diet and its association with primary liver cancer, suggesting that this dietary pattern was associated with a lower incidence risk of this cancer type (OR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.46–0.82).122

Diabetes-related outcomes

A total of 11 studies examined the relationship between traditional diets and diabetes-related outcomes, with the majority (n = 8) finding no association.16,64,83,84,89,91,116,118 Type 2 diabetes was not found to be associated with the traditional diets in one case–control study and one cross-sectional study.16,89 Additionally, 2 cross-sectional studies focused on prediabetes, and found no evidence of association with either the TCD (OR: 1.057, 95% CI: 0.933–1.199) or the traditional southern diet (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.757–1.826).64,83 One cross-sectional study suggested that higher adherence to the TCD was linked to lower risk of diabetes (OR: 0.810, 95% CI: 0.690–0.952).71 However, the other 3 studies showed no association.47,91,116

Four studies examined the influence of the TCD on glucose biological markers. One cohort study showed reduced concentrations of Hemoglobin A1C (–2.18%, 95% CI: –3.34% to –1.01%) and lower Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance indices (–10.34%, 95% CI: –16.92% to –3.24%), compared with populations consuming modern and high-wheat diets.47 A similar finding was also reported by another cohort study for hyperglycemia (RR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.35–0.99).52 However, there were contradictory findings in 2 cross-sectional studies, suggesting no association between the traditional southern diet and glycemic control (OR: 1.08, 95% CI: 0.889–1.322),84 or between the TCD and insulin resistance (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.62–1.76).118

Obesity-related outcomes

A total of 13 studies explored associations between the traditional diets and obesity-related outcomes; most of them (n = 8) showed that the TCD was associated with a lower risk of obesity and was inversely associated with weight gain.49,53,57,59,72,88,101,127 Five studies (RCT: n = 1; cross-sectional: n = 1; cohort: n = 3) reported differences in average body mass index/weight, with all of them showing that populations with highest adherence to the TCD had lower average body mass index/weight than those with the lowest adherence.49,57,59,101,127

Nine studies (cohort: n = 1; cross-sectional: n = 8) examined the association between traditional diets and central/general obesity, with 4 (cohort: n = 1; cross-sectional: n = 3) reporting reduced odds for obesity among those who had higher adherence to traditional diets.53,72,88,101 One cross-sectional study conducted analyses according to gender, indicating that the TCD was correlated with a higher risk of obesity in males (OR: 1.954, 95% CI: 1.258–3.036) but not in females (OR: 1.114, 95% CI: 0.759–1.636).98 Furthermore, 3 cross-sectional studies reported associations by region, suggesting that people following the traditional northern diet had a higher risk of obesity compared with people following the traditional southern diet.24,92,109 For example, in Zhang et al’s study, people in the highest quintiles of adherence to the traditional northern diet had greater odds of general obesity (OR: 2.28; 95% CI: 1.38–3.74) compared with people following the traditional southern diet (OR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.29–0.78).109

Kidney disease

Two cross-sectional studies explored association between the traditional southern diet and chronic kidney disease (CKD),87,104 and 3 studies (cohort: n = 1; cross-sectional: n = 2) explored the relationship between TCD and kidney-related dysfunction.51,66,85 However, the findings were inconsistent. Shi et al87 indicated a positive association between the traditional southern diet and increased CKD risk (OR: 4.56, 95% CI: 3.18–6.56), while Xu et al104 study found no association between them (OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.78–1.11). The cross-sectional study conducted by He et al66 reported that populations with a higher adherence to the TCD had a lower risk of hyperuricemia (OR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.426–0.922), while Shi85 showed a higher risk of hyperuricemia (OR: 3.24, 95% CI: 2.61–4.01) for this population group.

Hypertension

Eight cross-sectional studies reported on associations between the traditional diets and blood pressure, with varying findings.75,82,94,95,97,99,103,114 Three of them showed no association between the traditional diets and hypertension,97,99,114 but two studies suggested that, compared with populations with the lowest adherence to the TCD, those with the highest adherence had a higher prevalence of hypertension (PR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.18–1.82).82,95 Conversely, Xu et al103 found that adults with higher adherence to the TCD had a lower risk of hypertension (RR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.50–0.95). One study, which explored both the traditional northern diet and the traditional southern diet, reported that higher adherence to the traditional northern diet was associated with a higher risk of hypertension (OR: 1.30, 95% CI: 1.11–1.53), while higher adherence to the traditional southern diet was related to a lower risk of hypertension (OR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.59–0.89).94

Cardiovascular-related outcomes

Four studies assessed the association between traditional diets and CVD incidence (cohort: n = 2; cross-sectional: n = 2)69,71,79,83; 3 of them reported that adults with higher adherence to traditional diets could have a lower risk of CVD.55,56,75 However, 1 cross-sectional study explored the association between the traditional Tianjin diet and risk of CVD by gender, showing no association in either males (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.73–1.56) or females (OR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.61–1.33).71

Lipid-related outcomes

Five studies (cohort: n = 1; cross-sectional: n = 4) explored the association between traditional diets and lipid indices53,65,78,99,110; two of these (both cross-sectional) reported the findings by gender.65,78 Males seemed to have a higher risk of developing high total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) concentrations than females (OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1–1.21 and OR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.10–1.33 vs OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.75–1.03 and 0.96, 95% CI: 0.79–1.16, respectively).65 This finding was supported by the research of Lyu et al,78 who showed that males had a higher ratio of TGs (OR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.62–0.95), compared with females (OR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.69–1.07). However, no association was found between the traditional Jiangsu diet and high TC or TG risk (OR: 1.001, 95% CI: 0.834–1.201 and 0.940, 95% CI: 0.779–1.133, respectively).99 Zhang et al110 reported an inverse association between the traditional southern diet and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in females (beta coefficient β: –1.86, 95% CI: –3.39 to –0.33).

Other NCD-related outcomes

A total of 8 studies explored the association between traditional diets and other NCD-related outcomes (cohort: n = 3; cross-sectional: n = 5).58,60,62,69,74,86,100,107 One cross-sectional study reported that the traditional northern diet was associated with an elevated risk of stroke, compared with the traditional southern diet (OR: 1.82, 95% CI: 1.6–2.43).69 The population with higher adherence to the TCD also showed a higher risk of anemia and asthma.58,86 However, higher adherence to the TCD was reported to be inversely associated with metabolic syndrome risk (OR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.596–0.952).100 Three studies (cohort: n = 1; cross-sectional: n = 2) examined the relationship between TCD and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, endoscopic gastric mucosal atrophy, and non-alcohol fatty liver, respectively; no evidence of an association was found for any of these outcomes.62,74,107

Assessment of the risk of bias and quality of reporting

The assessment of risk of bias, separately for study design, is shown in Supplementary Materials I (see Table S12 in the Supporting Information online). Case–control studies were assessed as having high risk of bias in the definition of cases and the response rates for cases and controls. For cohort studies, even though half of them were assessed as having an overall low risk of bias, a potential risk in inadequate follow-up of cohorts was identified. The cross-sectional studies showed a potentially high risk of bias in the sample size, as most did not provide justification for this construct. The RCT was assessed as having a high risk of bias due to the missing outcome data and information on measurement of outcomes, as well as the lack of justification provided for deviations from intended interventions. Overall, no cohort studies, 25% of case–control studies (n = 1 of 4), 5% of cross-sectional studies (n = 2 of 37), and 100% of RCTs (n = 1 of 1) were assessed as having a high risk of bias.

Regarding the quality of reporting, no study reported all items required by the either STROBE statement or the CONSORT statement (Supplementary Materials I, see Table S13 and Figure S1 in the Supporting Information online). In relation to the STROBE statement, few studies justified the sample size or the analyses of subgroups/interactions. Only one study was assessed by using the CONSORT statement; in that study’s report, information was not reported on trial design, participants, outcomes, sample size, randomization, allocation concealment mechanism, blinding, statistical methods, recruitment, numbers analyzed, ancillary analyses, and harms.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically review the evidence in the existing literature to obtain a definition of the TCD, and to assess any associations between this dietary pattern, as described in the literature, and NCD outcomes. This systematic review revealed that rice and leafy fresh vegetables were the most-cited food groups constituting the overall TCD, and white rice, spinach, bokchoy, and cabbage were the most frequently cited food items characteristic of the TCD. Subgroup analyses indicated that food groups varied among regions. The traditional diets of minority groups were found to resemble the traditional diets of the Han population in areas where these groups coexisted. This finding diverged from that of a prior cohort study, which suggested a difference between the diets of minority groups and the Han majority.129 This disparity might be attributed to the limited number of included studies focusing on minority groups (n = 3) in this review. Investigations into the relationship between the TCD and health outcomes suggested that adherence to the traditional diet could lower the risk of obesity and prevent weight gain. Associations with other health outcomes remain unclear, however, which might be due to inconsistencies in the definition of the TCD used across studies.

Definition of the TCD

Rice and leafy fresh vegetables were the food groups with at least 75% citation frequency across studies. This finding is similar to that of a previous narrative review, which identified leafy vegetables, rice, and wheat as fundamental elements of the TCD.39 Wheat, corn and coarse grains have also previously been reported as main features of the TCD, suggesting their importance should be equal to that of rice,34,35 but in this review they were reported in fewer studies than rice. The regional traditions and the availability of wheat in northern China and rice in the south might be the main drivers of these differences across studies.46 As most of the studies included in the current systematic review were conducted in the south, this could have resulted in the studies referring to all regions showing a higher frequency of rice consumption than of wheat and wheat products.

The subgroup analyses revealed differences in the frequency of food groups between regions. For example, corn and coarse grains were reported for more studies in northern, compared with southern, China, according to the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line. This might be attributed to the higher production of corn and coarse grains in northern regions, which potentially influences food availability.131 Since the early 1980s, there has been a northward shift in the production of corn and coarse grains.131 Households in the northern regions have relied heavily on locally produced foods for essential nutrition,132 which potentially influenced the consumption of food groups in these regions. However, one study suggested that the majority of corn and coarse products were consumed in southern China, despite their production in northern China, which might be attributed to the development of inter-regional trade and economic disparities.133 Further studies are needed in order to clarify the varying frequencies of food group consumption across Chinese regions.

Studies referring to the north and east of China (according to the five-region classification system) found that people there were more likely to consume organ meats (liver and blood), and seeds and nuts (peanuts, pumpkin seeds, pistachios, almonds, walnuts, cashew nuts, sesame seeds). It is possible that these food groups are consumed to different extents in the different regions of the country due to cultural differences in eating habits. For example, gathering seeds and nuts has been an important custom contributing to plant-based sustenance in northern regions since the Yangshao period (around 5000–3000 BCE).134 Additionally, the consumption of organ meat has a long history in the east of China, dating back to the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE).44 In traditional Chinese medicine, organ meat is believed to have healing properties and is considered to be a nourishing food that can strengthen the body. Organ meat has also been associated with the concept of “yang” or warmth, which is considered beneficial for health in traditional Chinese culture.135,136

Some food groups, such as calorically sweetened beverages (eg, bubble tea), cakes (eg, soy pudding), animal-based milk products (milk, yogurt), instant foods (eg, instant noodles), organ meats, nuts and seeds were only mentioned in some studies, and with a relatively low frequency. It has been reported that alcoholic beverages, calorically sweetened beverages, cakes and animal-based dairy products, as well as instant foods, are more characteristic of a Western diet.137 This suggests that increased consumption of certain food groups has made the TCD become more similar to the Western diet over time.46 Additionally, considering that most of the included studies (n = 80) used a posteriori methods (such as PCA) to derive dietary patterns, the foods included in the TCD essentially reflected the current diets of the population but did not necessarily reflect the accurate traditional diet, even though they were defined as characteristic of the TCD by the included studies.

Wheat and wheat products (dumplings, cassava) were mostly reported as being inversely associated with the TCD (n = 19). However, at least 50% of studies in eastern and northern China reported that wheat was characteristic of the TCD. The overall inverse association was probably related to the unbalanced number of studies conducted in the north and the south that were included in this review. The traditional southern diet was recognized as having a high intake of rice and being inversely associated with wheat. In contrast, the traditional northern diet was usually characterized by high consumption of wheat and wheat products, as well as starchy roots and tubers, such as potatoes.69 As most of the included studies represented southern China, the inverse association between the TCD and wheat and starchy roots and tubers could be explained by this.

The consumption of rice, wheat, vegetables, and poultry has been a significant part of the TCD since the Qin Dynasty, dating back approximately 2230 years. This is often described as “5-grain for nourishment, 5 animals for the benefit,”138 and can be attributed to longstanding traditions of rice, grain, and cereal cultivation, coupled with poultry breeding, in China.139 During the Northern Song Dynasty, there was a notable shift toward lamb as the primary meat source, due to the thriving trade between the northern and southern regions of China, resulting in the transportation of significant quantities of lamb from the northern grasslands to the south.44 However, in more recent times, pork has emerged as the predominant food group within the TCD. This prominence of pork might have been influenced by evolving social customs and the active promotion of the pig industry.32,40,46 The consumption of soy products has also increased and has been a component of the TCD since the Song Dynasty. This is due to the recognition of soy’s edible value and the development of various techniques (such as fermentation) for preparing soy products.140 Furthermore, post-2000 research indicates that processed meats and soft drinks might be part of the TCD,83,84 but were absent in earlier TCD studies.32,40 This transition could be attributable to economic shifts and the adoption of contemporary research methodologies in more recent studies.46,141 In addition to the changes in food groups, cooking methods have also exhibited change over time. Before the 1990s, preservation and drying were popular as main cooking methods,14,42,44 but recent studies indicate that their popularity has declined. This trend may be linked to an increasing public awareness of health concerns, which has prompted investigation into the health impacts of these cooking methods.142 Therefore, the TCD has been influenced by environmental, cultural, and economic factors.143 Further research is essential in order to delineate the changes in the TCD components over time.

When trying to develop a consistent definition of the TCD for future research, some of the food groups identified should be considered cautiously. It might be possible to include nuts, seeds, and organ meat in the definition of the TCD, as these foods are still an important part of the diet in contemporary times, and they were mentioned by the included studies from several regions. However, beverages (such as soft drinks and juice), cakes, animal-based dairy products, and instant foods might not be as widely accepted as part of the TCD, as they might not have been part of the TCD in the past.

Differences in regional classification methods leading to TCD definition disparities

The reported frequencies of food groups consumed differed according to the method of regional classification. For example, the 5-regions classification method generated an eastern region, in which food groups that were characteristic of the diet were similar to those of the southern region as identified via the Qinling Mountains–Huaihe River line classification. Another example is that, compared with the food groups consumed within the original northern region, the northern area generated by the five-regions method featured more studies citing leafy fresh vegetables, fish, and rice as main food groups.