-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yiman Wang, Marc H Hemmelder, Willem Jan W Bos, Jaapjan D Snoep, Aiko P J de Vries, Friedo W Dekker, Yvette Meuleman, Mapping health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation by group comparisons: a systematic review, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 36, Issue 12, December 2021, Pages 2327–2339, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfab232

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is becoming an increasingly important outcome in kidney transplantation (KT). To describe HRQOL in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs), this systematic review summarizes literature that compared HRQOL among KTRs and other relevant populations [i.e. patients receiving dialysis, patients on the waiting list (WL) for KT, patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) not receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT), the general population (GP) and healthy controls (HCs)] and themselves before KT.

The literature search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. Eligible studies published between January 2000 and October 2020 were included.

Forty-four studies comprising 6929 KTRs were included in this systematic review. Despite the study heterogeneity, KTRs reported a higher HRQOL after KT compared with pre-transplantation and compared with patients receiving dialysis with or without being on the WL, especially in disease-specific domains (i.e. burden and effects of kidney disease). Additionally, KTRs had similar to marginally higher HRQOL compared with patients with CKD Stages 3–5 not receiving RRT. When compared with HCs or the GP, KTRs reported similar HRQOL in the first 1 or 2 years after KT and lower physical HRQOL and lower to comparable mental HRQOL in studies with longer post-transplant time.

The available evidence suggests that HRQOL improves after KT and can be restored to but not always maintained at pre-CKD HRQOL levels. Future studies investigating intervention targets to improve or maintain post-transplant HRQOL are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation (KT) is the preferred and cost-effective treatment for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) compared with long-term dialysis [1, 2]. Over the past decades, post-transplant graft and patient survival have improved considerably due to the availability of upgraded surgical techniques and innovative immunosuppressants [3]. The reported 5-year graft and patient survival rate of kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) exceeded 80% across different countries [3, 4]. However, KTRs often experience a considerable number of potential side effects (e.g. cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, neurotoxicity, infections and weight gain) due to the chronic immunosuppressive treatment required to maintain normal graft function [5]. Such treatment-related side effects, along with the underlying kidney disease and other comorbidities, are believed to negatively influence post-transplant health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [6]. In recent years, different international workgroups have recognized HRQOL as a valuable patient-centred outcome to assess treatment effects and healthcare quality in KT [7–9]. Therefore, knowledge of HRQOL after KT compared with other related conditions (e.g. dialysis) is also necessary to inform shared decision-making between patients with ESKD and healthcare professionals.

The most recent systematic review fulfilling this purpose compared HRQOL across different renal replacement therapies [RRTs; i.e. KT, haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD)] and showed better HRQOL in KTRs [10]. However, it only included articles published before 2005 and compared generic HRQOL measured by the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). With the considerable improvements in nephrology care and the exponential increase in studies focusing on HRQOL (and other related patient-reported outcomes), an updated overview of the current literature was urgently needed. Moreover, to gain a comprehensive picture of HRQOL in KTRs it is necessary to shed light on disease-specific HRQOL and HRQOL measured with other (non-SF-36) questionnaires and to include relevant comparison groups such as the general population (GP) and healthy controls (HCs) to better understand the extent to which HRQOL can be restored to a ‘pre-chronic kidney disease (CKD)’ level.

In this systematic review we describe and summarize the published literature to date that compares HRQOL after KT with that of all other relevant populations [i.e. patients receiving dialysis, patients on the waiting list (WL) for KT, patients with CKD not receiving RRT, the GP and HCs] and themselves before KT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. The protocol for this systematic review is registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42021223864).

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for inclusion in this review were KTRs >18 years of age at the time of transplantation with a single-organ KT; HRQOL as one of the outcomes; HRQOL in KTRs compared with that in the same cohort before KT, patients receiving dialysis, patients on the WL for KT, patients with CKD not receiving RRT, the GP and HCs via observational studies or randomized controlled trials; and original articles published between 1 January 2000 and 19 October 2020 in the English language.

Information sources and searching strategy

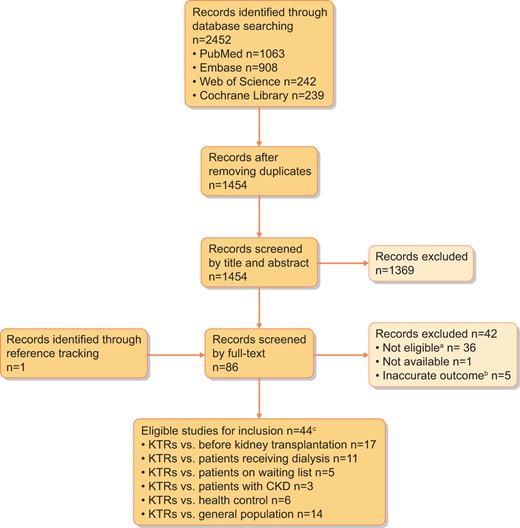

The literature research was conducted on 19 October 2020 using the Medical Subject Headings (MESH) keywords ‘kidney transplantation’ and ‘HRQOL’ (Supplementary data, Table S1) on PubMed (MEDLINE) to identify relevant studies, followed by a manual search in Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. Bibliographies of the included articles were also screened for studies missed by the searching strategy (Figure 1).

Study inclusion and exclusion flowchart. aInclusion criteria for full-text screening: subjects received single-organ transplantation in adults, disease-specific and/or generic HRQOL was measured post-transplantation and post-transplant HRQOL was compared with that of other populations, including the GP, HCs, patients with CKD not receiving RRT, patients on the WL and patients receiving dialysis. bInaccurate outcome: HRQOL scores higher than the maximum possible value, total HRQOL scores from a questionnaire that does not support such total score calculation or a higher HRQOL score as an indication for a worse HRQOL while the scoring algorithm hints the opposite (i.e. better HRQOL). cTen studies conducted more than one comparison.

Selection of articles

The screening of titles and abstracts for relevant articles was conducted by one researcher (Y.W.). Next, full texts of potentially relevant studies were screened by the main reviewer (Y.W.) in collaboration with a nephrologist (J.D.S.) and a medical psychologist (Y.M.). During the selection process, each article was marked as ‘inclusion’, ‘exclusion’ or ‘not sure’ based on pre-specified inclusion criteria. Any article marked ‘not sure’ was discussed among the reviewers to achieve consensus based on the pre-specified criteria. Articles not meeting the aforementioned eligibility criteria were excluded. Articles with poor accuracy of the outcome measurement [i.e. HRQOL scores higher than the maximum possible value, total HRQOL scores from a questionnaire that does not support such total score calculation or a higher HRQOL score as an indication for a worse HRQOL while the scoring algorithm hints the opposite (i.e. better HRQOL)] and unavailable full-text versions were excluded (Figure 1).

Extracted data items

Data extraction of pre-specified items was conducted by Y.W. and checked for accuracy by Y.M. Extracted data included demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (age, sex, time after transplantation for KTRs and percentage of living donor KT in KTRs), characteristics of the study [country where a study was conducted, study design, sample size, patient type (i.e. incident and prevalent), follow-up period, loss to follow-up (LOF) rate, response rate (RR) and statistical methods] and characteristics of the outcome (the questionnaire used to measure HRQOL, HRQOL scores and the statistical significance of the results).

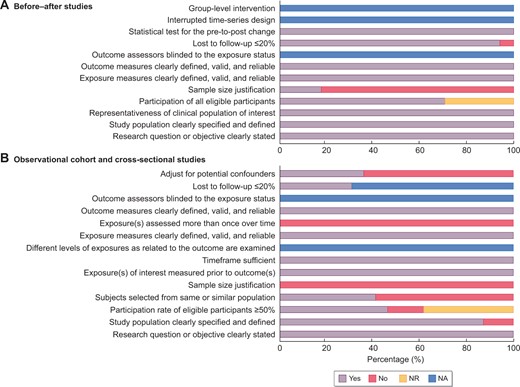

Study quality assessment and data synthesis

Following the PRISMA guidelines, the quality of the included studies was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tools for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies and Before–After Studies With No Control Group [12]. Studies were not excluded based on the quality assessment. A meta-analysis was not conducted due to the heterogeneity of the study population (i.e. prevalent and incident), questionnaires used to measure HRQOL, scoring algorithms to calculate HRQOL with the same questionnaire and inconsistent reporting of domain scores and summary scores. Therefore data were summarized narratively without pooled estimates for the outcome of interest.

RESULTS

Searching result

We identified 1454 unique records with the pre-specified searching strategy, of which 86 full-text articles were screened. Finally, 44 original studies were selected for this review (Figure 1) [13–56]. The sample sizes of KTRs in the included studies ranged from 15 to 1658 and the studies were conducted in 23 different countries, with Europe (45%) being the most common continent on which included studies were conducted. The characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1.

| References . | Year . | Country . | Study type . | KTR, n . | Comparison N group . | LOF, % . | RR, % . | Questionnaire . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease- specific . | Generic . | |||||||||

| Griva et al. [57] | 2012 | UK | R | 60 | Before KT | – | – | 98 | – | SF-36 |

| Das et al. [14] | 2014 | India | C (S) | 20 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | WHOQOL |

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 2015 | Thailand | R (S) | 232 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 2010 | UK | C (S) | 58 | Before KT | – | – | 77 | KTQ | SF-36 |

| HC | 38 | – | 32 | |||||||

| Lopes et al. [17] | 2013 | Portugal | P | 35 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 2014 | Brazil | P (S) | 63 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Virzi et al. [19] | 2007 | Italy | P | 48 | Before KT | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Balaska et al. [20] | 2006 | Grace | R (S) | 85 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 2015 | Netherlands | P (S) | 23 | Before KT | – | 18 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Painter et al. [22] | 2012 | USA | p | 20 | Before KT | – | 31 | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| Mousavi-Roknabadi et al. [23] | 2019 | Iran | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Gil et al. [24] | 2020 | Brazil | P (S) | 40 | Before KT | – | 7.5 | – | KRQOL | – |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 2019 | USA | R | 831 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 2020 | Japan | R (S) | 32 | Before KT | – | 13 | – | – | SF-36 |

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 2014 | Norway | p | 110 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | 5903 | – | ||||||||

| Lonning et al. [28] | 2018 | Norway | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 1 | 87–90 | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 2005 | UK | P (S) | 35 | Before KT | – | – | 72 | – | WHOQOL |

| UK GP | – | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 2020 | Nepal | C | 92 | HD (WL?) | 69 | – | 89 | – | WHOQOL |

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | Poland | C | 83 | HD (WL?) | 61 | – | 36 | – | WHOQOL | |

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 2000 | Japan | C (S) | 117 | HD & WL | 49 | – | 96 | – | SF-36 |

| HD not on WL | 65 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 2007 | Turkey | C | 20 | HD (WL?) | 75 | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 41 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 2018 | Japan | C (S) | 68 | HD (WL?) | 165 | – | – | – | SF36 |

| Rambod et al. [35] | 2011 | Iran | C | 200 | HD (WL?) | 200 | – | 100 | – | QLI-DT |

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 2013 | Nepal | C | 57 | HD (WL?) | 62 | – | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | 2014 | Poland | P | 120 | HD (WL?) | 50 | – | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 30 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 2014 | China | C (S) | 124 | HD (WL?) | 100 | – | 73 | – | SF-36 |

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 2010 | Slovak | P | 87 | WL | 93 | 1 | 69–89 | – | SF-36 |

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 2011 | Hungary | C | 888 | WL | 187 | – | 84 | KDQOL | – |

| Franke et al. [43] | 2000 | Germany | R (S) | 149 | WL | 149 | – | 80–90 | – | MLDL |

| HC | 149 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | R (S) | 139 | WL | 57 | – | – | – | |

| US GP | – | – | 81 | KTQ | SF-36 | |||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 2020 | France | C | 1658 | CKD 3b | 1487 | – | 84–100 | – | SF-36 |

| CKD 4 | 1206 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HD & PD (WL?) | 1251 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| French GP | 20574 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 2020 | Bangladesh | C (S) | 15 | CKD patients | 28 | – | – | KDQOL | – |

| HD (WL?) | 20 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HC | 40 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 2013 | Norway | C (S) | 38 | CKD patients | 30 | – | 59 | – | SF-36; VAS |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | |||||||

| Ay et al. [45] | 2015 | Turkey | P (S) | 47 | HC | 47 | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Taskintuna et al. [46] | 2009 | Turkey | C | 69 | HC | 45 | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Yagil et al. [47] | 2018 | Israel | C (S) | 45 | HC | 45 | – | 98 | – | SF-12 |

| Zhao et al. [49] | 2018 | China | C (S) | 253 | Chinese GP | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Cornella et al. [50] | 2008 | Italy | C (S) | 52 | Italian GP | 52 | – | 91 | – | SF-36 |

| Aasebo et al. [51] | 2009 | Norway | C | 131 | Norwegian GP | – | – | 47 | – | SF-36 |

| Karam et al. [52] | 2003 | France | C | 229 | French GP | 487 | – | 85 | – | NIDDK-QOL |

| Liu et al. [53] | 2015 | China | C | 204 | Chinese GP | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Esposito et al. [54] | 2017 | USA | C | 132 | US GP | – | – | 80 | – | SF-36 |

| Wei et al. [55] | 2013 | Taiwan | C (S) | 88 | Taiwanese GP | – | – | 63 | – | SF-36 |

| Costa-Requena et al. [56] | 2017 | Spain | P (S) | 124 | Spanish GP | – | – | 68–85 | KDQOL | – |

| References . | Year . | Country . | Study type . | KTR, n . | Comparison N group . | LOF, % . | RR, % . | Questionnaire . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease- specific . | Generic . | |||||||||

| Griva et al. [57] | 2012 | UK | R | 60 | Before KT | – | – | 98 | – | SF-36 |

| Das et al. [14] | 2014 | India | C (S) | 20 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | WHOQOL |

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 2015 | Thailand | R (S) | 232 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 2010 | UK | C (S) | 58 | Before KT | – | – | 77 | KTQ | SF-36 |

| HC | 38 | – | 32 | |||||||

| Lopes et al. [17] | 2013 | Portugal | P | 35 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 2014 | Brazil | P (S) | 63 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Virzi et al. [19] | 2007 | Italy | P | 48 | Before KT | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Balaska et al. [20] | 2006 | Grace | R (S) | 85 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 2015 | Netherlands | P (S) | 23 | Before KT | – | 18 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Painter et al. [22] | 2012 | USA | p | 20 | Before KT | – | 31 | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| Mousavi-Roknabadi et al. [23] | 2019 | Iran | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Gil et al. [24] | 2020 | Brazil | P (S) | 40 | Before KT | – | 7.5 | – | KRQOL | – |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 2019 | USA | R | 831 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 2020 | Japan | R (S) | 32 | Before KT | – | 13 | – | – | SF-36 |

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 2014 | Norway | p | 110 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | 5903 | – | ||||||||

| Lonning et al. [28] | 2018 | Norway | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 1 | 87–90 | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 2005 | UK | P (S) | 35 | Before KT | – | – | 72 | – | WHOQOL |

| UK GP | – | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 2020 | Nepal | C | 92 | HD (WL?) | 69 | – | 89 | – | WHOQOL |

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | Poland | C | 83 | HD (WL?) | 61 | – | 36 | – | WHOQOL | |

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 2000 | Japan | C (S) | 117 | HD & WL | 49 | – | 96 | – | SF-36 |

| HD not on WL | 65 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 2007 | Turkey | C | 20 | HD (WL?) | 75 | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 41 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 2018 | Japan | C (S) | 68 | HD (WL?) | 165 | – | – | – | SF36 |

| Rambod et al. [35] | 2011 | Iran | C | 200 | HD (WL?) | 200 | – | 100 | – | QLI-DT |

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 2013 | Nepal | C | 57 | HD (WL?) | 62 | – | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | 2014 | Poland | P | 120 | HD (WL?) | 50 | – | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 30 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 2014 | China | C (S) | 124 | HD (WL?) | 100 | – | 73 | – | SF-36 |

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 2010 | Slovak | P | 87 | WL | 93 | 1 | 69–89 | – | SF-36 |

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 2011 | Hungary | C | 888 | WL | 187 | – | 84 | KDQOL | – |

| Franke et al. [43] | 2000 | Germany | R (S) | 149 | WL | 149 | – | 80–90 | – | MLDL |

| HC | 149 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | R (S) | 139 | WL | 57 | – | – | – | |

| US GP | – | – | 81 | KTQ | SF-36 | |||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 2020 | France | C | 1658 | CKD 3b | 1487 | – | 84–100 | – | SF-36 |

| CKD 4 | 1206 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HD & PD (WL?) | 1251 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| French GP | 20574 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 2020 | Bangladesh | C (S) | 15 | CKD patients | 28 | – | – | KDQOL | – |

| HD (WL?) | 20 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HC | 40 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 2013 | Norway | C (S) | 38 | CKD patients | 30 | – | 59 | – | SF-36; VAS |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | |||||||

| Ay et al. [45] | 2015 | Turkey | P (S) | 47 | HC | 47 | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Taskintuna et al. [46] | 2009 | Turkey | C | 69 | HC | 45 | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Yagil et al. [47] | 2018 | Israel | C (S) | 45 | HC | 45 | – | 98 | – | SF-12 |

| Zhao et al. [49] | 2018 | China | C (S) | 253 | Chinese GP | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Cornella et al. [50] | 2008 | Italy | C (S) | 52 | Italian GP | 52 | – | 91 | – | SF-36 |

| Aasebo et al. [51] | 2009 | Norway | C | 131 | Norwegian GP | – | – | 47 | – | SF-36 |

| Karam et al. [52] | 2003 | France | C | 229 | French GP | 487 | – | 85 | – | NIDDK-QOL |

| Liu et al. [53] | 2015 | China | C | 204 | Chinese GP | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Esposito et al. [54] | 2017 | USA | C | 132 | US GP | – | – | 80 | – | SF-36 |

| Wei et al. [55] | 2013 | Taiwan | C (S) | 88 | Taiwanese GP | – | – | 63 | – | SF-36 |

| Costa-Requena et al. [56] | 2017 | Spain | P (S) | 124 | Spanish GP | – | – | 68–85 | KDQOL | – |

‘WL?’ indicates unknown WL status. ‘–’ indicates NA or NR. C, cross-sectional study; KTQ, Kidney Transplant Questionnaire; MLDL, Munich Life Quality Dimension List; NIDDK-QOL, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Liver Transplant Database Quality of Life Questionnaire; P, prospective study; QLI-DT, Quality and Life Index Questionnaire Dialysis and Transplantation; R, retrospective study; S, single centre.

| References . | Year . | Country . | Study type . | KTR, n . | Comparison N group . | LOF, % . | RR, % . | Questionnaire . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease- specific . | Generic . | |||||||||

| Griva et al. [57] | 2012 | UK | R | 60 | Before KT | – | – | 98 | – | SF-36 |

| Das et al. [14] | 2014 | India | C (S) | 20 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | WHOQOL |

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 2015 | Thailand | R (S) | 232 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 2010 | UK | C (S) | 58 | Before KT | – | – | 77 | KTQ | SF-36 |

| HC | 38 | – | 32 | |||||||

| Lopes et al. [17] | 2013 | Portugal | P | 35 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 2014 | Brazil | P (S) | 63 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Virzi et al. [19] | 2007 | Italy | P | 48 | Before KT | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Balaska et al. [20] | 2006 | Grace | R (S) | 85 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 2015 | Netherlands | P (S) | 23 | Before KT | – | 18 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Painter et al. [22] | 2012 | USA | p | 20 | Before KT | – | 31 | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| Mousavi-Roknabadi et al. [23] | 2019 | Iran | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Gil et al. [24] | 2020 | Brazil | P (S) | 40 | Before KT | – | 7.5 | – | KRQOL | – |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 2019 | USA | R | 831 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 2020 | Japan | R (S) | 32 | Before KT | – | 13 | – | – | SF-36 |

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 2014 | Norway | p | 110 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | 5903 | – | ||||||||

| Lonning et al. [28] | 2018 | Norway | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 1 | 87–90 | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 2005 | UK | P (S) | 35 | Before KT | – | – | 72 | – | WHOQOL |

| UK GP | – | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 2020 | Nepal | C | 92 | HD (WL?) | 69 | – | 89 | – | WHOQOL |

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | Poland | C | 83 | HD (WL?) | 61 | – | 36 | – | WHOQOL | |

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 2000 | Japan | C (S) | 117 | HD & WL | 49 | – | 96 | – | SF-36 |

| HD not on WL | 65 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 2007 | Turkey | C | 20 | HD (WL?) | 75 | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 41 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 2018 | Japan | C (S) | 68 | HD (WL?) | 165 | – | – | – | SF36 |

| Rambod et al. [35] | 2011 | Iran | C | 200 | HD (WL?) | 200 | – | 100 | – | QLI-DT |

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 2013 | Nepal | C | 57 | HD (WL?) | 62 | – | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | 2014 | Poland | P | 120 | HD (WL?) | 50 | – | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 30 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 2014 | China | C (S) | 124 | HD (WL?) | 100 | – | 73 | – | SF-36 |

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 2010 | Slovak | P | 87 | WL | 93 | 1 | 69–89 | – | SF-36 |

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 2011 | Hungary | C | 888 | WL | 187 | – | 84 | KDQOL | – |

| Franke et al. [43] | 2000 | Germany | R (S) | 149 | WL | 149 | – | 80–90 | – | MLDL |

| HC | 149 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | R (S) | 139 | WL | 57 | – | – | – | |

| US GP | – | – | 81 | KTQ | SF-36 | |||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 2020 | France | C | 1658 | CKD 3b | 1487 | – | 84–100 | – | SF-36 |

| CKD 4 | 1206 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HD & PD (WL?) | 1251 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| French GP | 20574 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 2020 | Bangladesh | C (S) | 15 | CKD patients | 28 | – | – | KDQOL | – |

| HD (WL?) | 20 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HC | 40 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 2013 | Norway | C (S) | 38 | CKD patients | 30 | – | 59 | – | SF-36; VAS |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | |||||||

| Ay et al. [45] | 2015 | Turkey | P (S) | 47 | HC | 47 | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Taskintuna et al. [46] | 2009 | Turkey | C | 69 | HC | 45 | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Yagil et al. [47] | 2018 | Israel | C (S) | 45 | HC | 45 | – | 98 | – | SF-12 |

| Zhao et al. [49] | 2018 | China | C (S) | 253 | Chinese GP | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Cornella et al. [50] | 2008 | Italy | C (S) | 52 | Italian GP | 52 | – | 91 | – | SF-36 |

| Aasebo et al. [51] | 2009 | Norway | C | 131 | Norwegian GP | – | – | 47 | – | SF-36 |

| Karam et al. [52] | 2003 | France | C | 229 | French GP | 487 | – | 85 | – | NIDDK-QOL |

| Liu et al. [53] | 2015 | China | C | 204 | Chinese GP | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Esposito et al. [54] | 2017 | USA | C | 132 | US GP | – | – | 80 | – | SF-36 |

| Wei et al. [55] | 2013 | Taiwan | C (S) | 88 | Taiwanese GP | – | – | 63 | – | SF-36 |

| Costa-Requena et al. [56] | 2017 | Spain | P (S) | 124 | Spanish GP | – | – | 68–85 | KDQOL | – |

| References . | Year . | Country . | Study type . | KTR, n . | Comparison N group . | LOF, % . | RR, % . | Questionnaire . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease- specific . | Generic . | |||||||||

| Griva et al. [57] | 2012 | UK | R | 60 | Before KT | – | – | 98 | – | SF-36 |

| Das et al. [14] | 2014 | India | C (S) | 20 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | WHOQOL |

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 2015 | Thailand | R (S) | 232 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 2010 | UK | C (S) | 58 | Before KT | – | – | 77 | KTQ | SF-36 |

| HC | 38 | – | 32 | |||||||

| Lopes et al. [17] | 2013 | Portugal | P | 35 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 2014 | Brazil | P (S) | 63 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Virzi et al. [19] | 2007 | Italy | P | 48 | Before KT | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Balaska et al. [20] | 2006 | Grace | R (S) | 85 | Before KT | – | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 2015 | Netherlands | P (S) | 23 | Before KT | – | 18 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Painter et al. [22] | 2012 | USA | p | 20 | Before KT | – | 31 | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| Mousavi-Roknabadi et al. [23] | 2019 | Iran | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | – | SF-36 |

| Gil et al. [24] | 2020 | Brazil | P (S) | 40 | Before KT | – | 7.5 | – | KRQOL | – |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 2019 | USA | R | 831 | Before KT | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 2020 | Japan | R (S) | 32 | Before KT | – | 13 | – | – | SF-36 |

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 2014 | Norway | p | 110 | Before KT | – | 0 | – | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | 5903 | – | ||||||||

| Lonning et al. [28] | 2018 | Norway | P (S) | 120 | Before KT | – | 1 | 87–90 | KDQOL | – |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 2005 | UK | P (S) | 35 | Before KT | – | – | 72 | – | WHOQOL |

| UK GP | – | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 2020 | Nepal | C | 92 | HD (WL?) | 69 | – | 89 | – | WHOQOL |

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | Poland | C | 83 | HD (WL?) | 61 | – | 36 | – | WHOQOL | |

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 2000 | Japan | C (S) | 117 | HD & WL | 49 | – | 96 | – | SF-36 |

| HD not on WL | 65 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 2007 | Turkey | C | 20 | HD (WL?) | 75 | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 41 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 2018 | Japan | C (S) | 68 | HD (WL?) | 165 | – | – | – | SF36 |

| Rambod et al. [35] | 2011 | Iran | C | 200 | HD (WL?) | 200 | – | 100 | – | QLI-DT |

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 2013 | Nepal | C | 57 | HD (WL?) | 62 | – | – | – | WHOQOL |

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | 2014 | Poland | P | 120 | HD (WL?) | 50 | – | – | KDQOL | SF-36 |

| PD (WL?) | 30 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 2014 | China | C (S) | 124 | HD (WL?) | 100 | – | 73 | – | SF-36 |

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 2010 | Slovak | P | 87 | WL | 93 | 1 | 69–89 | – | SF-36 |

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 2011 | Hungary | C | 888 | WL | 187 | – | 84 | KDQOL | – |

| Franke et al. [43] | 2000 | Germany | R (S) | 149 | WL | 149 | – | 80–90 | – | MLDL |

| HC | 149 | – | – | – | ||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 2006 | USA | R (S) | 139 | WL | 57 | – | – | – | |

| US GP | – | – | 81 | KTQ | SF-36 | |||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 2020 | France | C | 1658 | CKD 3b | 1487 | – | 84–100 | – | SF-36 |

| CKD 4 | 1206 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HD & PD (WL?) | 1251 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| French GP | 20574 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 2020 | Bangladesh | C (S) | 15 | CKD patients | 28 | – | – | KDQOL | – |

| HD (WL?) | 20 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| HC | 40 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 2013 | Norway | C (S) | 38 | CKD patients | 30 | – | 59 | – | SF-36; VAS |

| Norwegian GP | – | – | – | |||||||

| Ay et al. [45] | 2015 | Turkey | P (S) | 47 | HC | 47 | 0 | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Taskintuna et al. [46] | 2009 | Turkey | C | 69 | HC | 45 | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Yagil et al. [47] | 2018 | Israel | C (S) | 45 | HC | 45 | – | 98 | – | SF-12 |

| Zhao et al. [49] | 2018 | China | C (S) | 253 | Chinese GP | – | – | – | – | SF-36 |

| Cornella et al. [50] | 2008 | Italy | C (S) | 52 | Italian GP | 52 | – | 91 | – | SF-36 |

| Aasebo et al. [51] | 2009 | Norway | C | 131 | Norwegian GP | – | – | 47 | – | SF-36 |

| Karam et al. [52] | 2003 | France | C | 229 | French GP | 487 | – | 85 | – | NIDDK-QOL |

| Liu et al. [53] | 2015 | China | C | 204 | Chinese GP | – | – | 100 | – | SF-36 |

| Esposito et al. [54] | 2017 | USA | C | 132 | US GP | – | – | 80 | – | SF-36 |

| Wei et al. [55] | 2013 | Taiwan | C (S) | 88 | Taiwanese GP | – | – | 63 | – | SF-36 |

| Costa-Requena et al. [56] | 2017 | Spain | P (S) | 124 | Spanish GP | – | – | 68–85 | KDQOL | – |

‘WL?’ indicates unknown WL status. ‘–’ indicates NA or NR. C, cross-sectional study; KTQ, Kidney Transplant Questionnaire; MLDL, Munich Life Quality Dimension List; NIDDK-QOL, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Liver Transplant Database Quality of Life Questionnaire; P, prospective study; QLI-DT, Quality and Life Index Questionnaire Dialysis and Transplantation; R, retrospective study; S, single centre.

KTRs studied

The mean age of KTRs at the time of HRQOL measurement ranged from 29 to 72 years and only two studies were conducted in an elderly cohort >60 years of age (n = 43). The majority of studies (93%) reported a higher percentage of male KTRs [median 62% (range 43–86); n = 43]. The average time of HRQOL measurements after KT ranged from 1 to 234 months after the operation (median 12 months; n = 35). Twenty-three studies reported the donor type for KT and the percentage of living donor KTs (LDKTs) ranged from 3.3% to 100% (median 100%). Data on comorbidities, dialysis vintage and primary kidney disease were infrequently reported and could therefore not be systematically collected within this review. All characteristics of KTRs are presented in Tables 2–4.

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL . | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | RRT before KT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV . | Total . | |||

| Mousavi- Roknabadi et al. [23] | 39 | 65 | 37 | – | 3 | Mean rank (after/ before) | – | 55/50e | 40/27e | 48/47e | 65/13e | – | 56/24e | 49/54e | 47/26e | 54/30e | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 51 | 64 | 100 | 36 | 3 | Mean change | – | 6 | 24b | 0 | 15b | – | 18b | 16b | 10 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Gil et al. [24] | 36 | 65 | 100 | – | 3 | Mean (after/before) | 52/43b | 93/75b | 81/35b | 92/85 | 78/60b | 56/46b | 74/58b | 92/64b | 93/58b | 86/70b | - | 78/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | 51/43b | 94/75b | 70/35b | 80/82 | 70/60b | 53/46b | 76/58b | 80/64b | 79/58b | 85/70b | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Virzi et al. [19] | 41a | 58 | 100 | 92 | 6 | Mean (after/before) | 77/72 | 58/38e | 21/32c | 78/70c | 63/56c | 62/49c | - | 77/60c | - | 74/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Griva et al. [57] | 43 | 54 | 3 | 100 | 6 | Cohen's d | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Painter et al. [22] | 44 | 85 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean change | 7b | 7b | 11b | 3b | 5b | 2 | 7b | 15b | 3 | 0 | 9b | 19b | 24b | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lopes et al. [17] | 37a | 63 | 100 | – | 12 | Median (after/ before) | 100/70b | 100/25b | 100/72b | 72/40b | – | 80/55b | 100/62b | 100/100b | 84/68b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 44a | 86 | 100 | 38 | 3 | % > MCID (PEKT/ non-PEKT) | 40/40 | 40/45 | 80/60 | 20/35 | 70/60 | 55/60 | 55/70 | 70/65 | 35/30 | 60/60 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 12 | 50/33 | 33/50 | 33/25 | 25/25 | 83/92 | 58/75 | 67/83 | 67/58 | 33/33 | 50/42 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Balaska et al. [20] | 44a | 52 | 54 | 100 | 12 | Mean (after/before) | – | 77/56 | 62/10c | 90/46 | 84/34d | – | 83/26c | 78/31 | 83/40c | 68/23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 48 | 67 | 34 | - | 12 | % > MCID | – | 37 | 58 | 39 | 39 | – | 42 | 41 | 44 | 23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lonning et al. [28] | 72 | 71 | 21 | 90 | 2 | Mean difference (SD) | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| 12 | – | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 57 | 66 | – | 100 | 40 | Mean differenceb | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5b | <0.5 | >0.5d | >0.5d | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 39a | 53 | 100 | – | 46 | Mean (after/before) | 65/35c | 71/48c | 65/17c | 72/59 | 54/22c | 69/39c | 63/30c | 77/43c | 76/44c | 79/59c | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Das et al. [14] | 60%: 30–45g | 80 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 76/47c | 84/47c | 77/62c | 74/55c | – | |

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 37a | 51 | 100 | – | 1.5 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 15/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 17/16 | – | |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 16/16 | – | |||||||

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 88%: 33–60g | 62 | – | – | – | Mean difference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | - | - | - | - | 29c | |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 39 | 62 | – | 97 | – | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17/10c | 18/13c | 17/13c | 14/12c | 18/9c | |

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL . | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | RRT before KT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV . | Total . | |||

| Mousavi- Roknabadi et al. [23] | 39 | 65 | 37 | – | 3 | Mean rank (after/ before) | – | 55/50e | 40/27e | 48/47e | 65/13e | – | 56/24e | 49/54e | 47/26e | 54/30e | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 51 | 64 | 100 | 36 | 3 | Mean change | – | 6 | 24b | 0 | 15b | – | 18b | 16b | 10 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Gil et al. [24] | 36 | 65 | 100 | – | 3 | Mean (after/before) | 52/43b | 93/75b | 81/35b | 92/85 | 78/60b | 56/46b | 74/58b | 92/64b | 93/58b | 86/70b | - | 78/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | 51/43b | 94/75b | 70/35b | 80/82 | 70/60b | 53/46b | 76/58b | 80/64b | 79/58b | 85/70b | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Virzi et al. [19] | 41a | 58 | 100 | 92 | 6 | Mean (after/before) | 77/72 | 58/38e | 21/32c | 78/70c | 63/56c | 62/49c | - | 77/60c | - | 74/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Griva et al. [57] | 43 | 54 | 3 | 100 | 6 | Cohen's d | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Painter et al. [22] | 44 | 85 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean change | 7b | 7b | 11b | 3b | 5b | 2 | 7b | 15b | 3 | 0 | 9b | 19b | 24b | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lopes et al. [17] | 37a | 63 | 100 | – | 12 | Median (after/ before) | 100/70b | 100/25b | 100/72b | 72/40b | – | 80/55b | 100/62b | 100/100b | 84/68b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 44a | 86 | 100 | 38 | 3 | % > MCID (PEKT/ non-PEKT) | 40/40 | 40/45 | 80/60 | 20/35 | 70/60 | 55/60 | 55/70 | 70/65 | 35/30 | 60/60 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 12 | 50/33 | 33/50 | 33/25 | 25/25 | 83/92 | 58/75 | 67/83 | 67/58 | 33/33 | 50/42 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Balaska et al. [20] | 44a | 52 | 54 | 100 | 12 | Mean (after/before) | – | 77/56 | 62/10c | 90/46 | 84/34d | – | 83/26c | 78/31 | 83/40c | 68/23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 48 | 67 | 34 | - | 12 | % > MCID | – | 37 | 58 | 39 | 39 | – | 42 | 41 | 44 | 23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lonning et al. [28] | 72 | 71 | 21 | 90 | 2 | Mean difference (SD) | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| 12 | – | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 57 | 66 | – | 100 | 40 | Mean differenceb | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5b | <0.5 | >0.5d | >0.5d | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 39a | 53 | 100 | – | 46 | Mean (after/before) | 65/35c | 71/48c | 65/17c | 72/59 | 54/22c | 69/39c | 63/30c | 77/43c | 76/44c | 79/59c | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Das et al. [14] | 60%: 30–45g | 80 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 76/47c | 84/47c | 77/62c | 74/55c | – | |

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 37a | 51 | 100 | – | 1.5 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 15/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 17/16 | – | |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 16/16 | – | |||||||

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 88%: 33–60g | 62 | – | – | – | Mean difference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | - | - | - | - | 29c | |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 39 | 62 | – | 97 | – | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17/10c | 18/13c | 17/13c | 14/12c | 18/9c | |

Continuous variables are presented as the mean if not otherwise indicated. HRQOL results are presented in bold if they were reportedly significant according to statistical testing (P < 0.05) or a threshold for mean difference (difference > 0.5 SD or Cohen’s d > 0) or the percentages of patients who reported an improvement larger than MCID >50%.

–, not reported; ENV, environmental; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; PHY, physical; PSY, psychological; S, symptom; SOC, social.

Values presented as median.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.0001.

Statistical test conducted for comparison at three time points (before KT, 1.5 and 12 months after KT) and P < 0.05.

Percentage within the indicated range.

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL . | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | RRT before KT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV . | Total . | |||

| Mousavi- Roknabadi et al. [23] | 39 | 65 | 37 | – | 3 | Mean rank (after/ before) | – | 55/50e | 40/27e | 48/47e | 65/13e | – | 56/24e | 49/54e | 47/26e | 54/30e | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 51 | 64 | 100 | 36 | 3 | Mean change | – | 6 | 24b | 0 | 15b | – | 18b | 16b | 10 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Gil et al. [24] | 36 | 65 | 100 | – | 3 | Mean (after/before) | 52/43b | 93/75b | 81/35b | 92/85 | 78/60b | 56/46b | 74/58b | 92/64b | 93/58b | 86/70b | - | 78/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | 51/43b | 94/75b | 70/35b | 80/82 | 70/60b | 53/46b | 76/58b | 80/64b | 79/58b | 85/70b | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Virzi et al. [19] | 41a | 58 | 100 | 92 | 6 | Mean (after/before) | 77/72 | 58/38e | 21/32c | 78/70c | 63/56c | 62/49c | - | 77/60c | - | 74/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Griva et al. [57] | 43 | 54 | 3 | 100 | 6 | Cohen's d | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Painter et al. [22] | 44 | 85 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean change | 7b | 7b | 11b | 3b | 5b | 2 | 7b | 15b | 3 | 0 | 9b | 19b | 24b | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lopes et al. [17] | 37a | 63 | 100 | – | 12 | Median (after/ before) | 100/70b | 100/25b | 100/72b | 72/40b | – | 80/55b | 100/62b | 100/100b | 84/68b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 44a | 86 | 100 | 38 | 3 | % > MCID (PEKT/ non-PEKT) | 40/40 | 40/45 | 80/60 | 20/35 | 70/60 | 55/60 | 55/70 | 70/65 | 35/30 | 60/60 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 12 | 50/33 | 33/50 | 33/25 | 25/25 | 83/92 | 58/75 | 67/83 | 67/58 | 33/33 | 50/42 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Balaska et al. [20] | 44a | 52 | 54 | 100 | 12 | Mean (after/before) | – | 77/56 | 62/10c | 90/46 | 84/34d | – | 83/26c | 78/31 | 83/40c | 68/23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 48 | 67 | 34 | - | 12 | % > MCID | – | 37 | 58 | 39 | 39 | – | 42 | 41 | 44 | 23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lonning et al. [28] | 72 | 71 | 21 | 90 | 2 | Mean difference (SD) | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| 12 | – | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 57 | 66 | – | 100 | 40 | Mean differenceb | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5b | <0.5 | >0.5d | >0.5d | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 39a | 53 | 100 | – | 46 | Mean (after/before) | 65/35c | 71/48c | 65/17c | 72/59 | 54/22c | 69/39c | 63/30c | 77/43c | 76/44c | 79/59c | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Das et al. [14] | 60%: 30–45g | 80 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 76/47c | 84/47c | 77/62c | 74/55c | – | |

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 37a | 51 | 100 | – | 1.5 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 15/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 17/16 | – | |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 16/16 | – | |||||||

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 88%: 33–60g | 62 | – | – | – | Mean difference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | - | - | - | - | 29c | |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 39 | 62 | – | 97 | – | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17/10c | 18/13c | 17/13c | 14/12c | 18/9c | |

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL . | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | RRT before KT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV . | Total . | |||

| Mousavi- Roknabadi et al. [23] | 39 | 65 | 37 | – | 3 | Mean rank (after/ before) | – | 55/50e | 40/27e | 48/47e | 65/13e | – | 56/24e | 49/54e | 47/26e | 54/30e | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Russcher et al. [21] | 51 | 64 | 100 | 36 | 3 | Mean change | – | 6 | 24b | 0 | 15b | – | 18b | 16b | 10 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Gil et al. [24] | 36 | 65 | 100 | – | 3 | Mean (after/before) | 52/43b | 93/75b | 81/35b | 92/85 | 78/60b | 56/46b | 74/58b | 92/64b | 93/58b | 86/70b | - | 78/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | 51/43b | 94/75b | 70/35b | 80/82 | 70/60b | 53/46b | 76/58b | 80/64b | 79/58b | 85/70b | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Virzi et al. [19] | 41a | 58 | 100 | 92 | 6 | Mean (after/before) | 77/72 | 58/38e | 21/32c | 78/70c | 63/56c | 62/49c | - | 77/60c | - | 74/41b | - | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Griva et al. [57] | 43 | 54 | 3 | 100 | 6 | Cohen's d | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Painter et al. [22] | 44 | 85 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean change | 7b | 7b | 11b | 3b | 5b | 2 | 7b | 15b | 3 | 0 | 9b | 19b | 24b | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lopes et al. [17] | 37a | 63 | 100 | – | 12 | Median (after/ before) | 100/70b | 100/25b | 100/72b | 72/40b | – | 80/55b | 100/62b | 100/100b | 84/68b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Mitsui et al. [26] | 44a | 86 | 100 | 38 | 3 | % > MCID (PEKT/ non-PEKT) | 40/40 | 40/45 | 80/60 | 20/35 | 70/60 | 55/60 | 55/70 | 70/65 | 35/30 | 60/60 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 12 | 50/33 | 33/50 | 33/25 | 25/25 | 83/92 | 58/75 | 67/83 | 67/58 | 33/33 | 50/42 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Balaska et al. [20] | 44a | 52 | 54 | 100 | 12 | Mean (after/before) | – | 77/56 | 62/10c | 90/46 | 84/34d | – | 83/26c | 78/31 | 83/40c | 68/23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Purnajo et al. [25] | 48 | 67 | 34 | - | 12 | % > MCID | – | 37 | 58 | 39 | 39 | – | 42 | 41 | 44 | 23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lonning et al. [28] | 72 | 71 | 21 | 90 | 2 | Mean difference (SD) | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 6 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| 12 | – | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | – | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| von der Lippe et al. [27] | 57 | 66 | – | 100 | 40 | Mean differenceb | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | – | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5b | <0.5 | >0.5d | >0.5d | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Shrestha et al. [16] | 39a | 53 | 100 | – | 46 | Mean (after/before) | 65/35c | 71/48c | 65/17c | 72/59 | 54/22c | 69/39c | 63/30c | 77/43c | 76/44c | 79/59c | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Das et al. [14] | 60%: 30–45g | 80 | 100 | – | 6 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 76/47c | 84/47c | 77/62c | 74/55c | – | |

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 37a | 51 | 100 | – | 1.5 | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 15/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 17/16 | – | |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16/11f | 16/15 | 16/16 | 16/16 | – | |||||||

| Junchotikul et al. [15] | 88%: 33–60g | 62 | – | – | – | Mean difference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | - | - | - | - | 29c | |

| Mendonca et al. [18] | 39 | 62 | – | 97 | – | Mean (after/before) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17/10c | 18/13c | 17/13c | 14/12c | 18/9c | |

Continuous variables are presented as the mean if not otherwise indicated. HRQOL results are presented in bold if they were reportedly significant according to statistical testing (P < 0.05) or a threshold for mean difference (difference > 0.5 SD or Cohen’s d > 0) or the percentages of patients who reported an improvement larger than MCID >50%.

–, not reported; ENV, environmental; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; PHY, physical; PSY, psychological; S, symptom; SOC, social.

Values presented as median.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.0001.

Statistical test conducted for comparison at three time points (before KT, 1.5 and 12 months after KT) and P < 0.05.

Percentage within the indicated range.

HRQOL of KTRs compared with patients on dialysis (n = 11), patients on the WL (n = 5) and patients with CKD not receiving RRT (n = 3)

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL or QLI-DT . | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTRs . | Patients on dialysis/with CKD . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | RRT . | Time on dialysis (months) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV/FAM . | Total . | ||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | – | 55 | – | 3 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35b | 72/50b | 42/30 | 78/46 | 45/28 | 45/44 | 58/49 | 70/59 | 65/47 | 64/61 | 85/66b | 76/54b | 48/30b | |||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 45/38b | 72/52b | 42/36 | 78/66 | 45/42 | 45/50 | 58/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 64/50 | 85/74b | 77/65b | 48/54b | |||||||||||

| 12 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | 46/35b | 76/50b | 50/30 | 67/46 | 44/28b | 44/44 | 56/49b | 70/59 | 65/48 | 63/61 | 83/66b | 78/54b | 56/30b | ||||||||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 46/38b | 76/52b | 50/36 | 67/66 | 44/42 | 44/50 | 56/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 63/50 | 83/74 | 79/65 | 53/54b | |||||||||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 33 | 65 | 70 | 41 | 47 | 72 | HD | 46 | Mean (KT/D) | 69/56 | 43/41 | 64/63 | 50/40 | 68/56g | 58/63 | 46/30 | 66/58 | ||||||||||

| 46 | 61 | PD | 35 | 69/56 | 43/39 | 64/66 | 50/41 | 68/52g | 58/56 | 46/46 | 66/61 | ||||||||||||||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 34 | 78 | 100 | 39a | – | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 80/68d | 74/35d | 72/62d | 67/40d | 64/46d | 75/55d | 77/42d | 72/59d | ||||||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 52 | 60 | 100 | 47a | 53 | 48 | HD | – | Mean (KT/D) | 47/23c | 46/20c | 49/43c | 45/40c | 51/41c | 49/38c | 48/35c | 52/49c | ||||||||||

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 69 | HD | 92 | Mean (KT/D) | 86/82 | 78/64b | 80/67b | 56/52 | 63/58 | 82/74b | 78/70 | 70/69 | ||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 69 | 65 | D | >12 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35d | 46/40d | ||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 43 | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 91/37f | 30/0f | 69/30f | 48/21f | – | 66/40f | 70/24f | 33/0f | 56/41f | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 39 | 75 | – | >6 | 44 | 75 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 13/11d | 14/11d | 14/13b | 12/11c | 13/11d | |||||||||||||

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 41 | 70 | – | 72%: 3–24h | 46 | 68 | HD | 76%: 3–24h | Mean (KT/D) | 70/49d | 69/52d | 69/58d | 60/56d | 267/215d | |||||||||||||

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | 43 | 52 | – | 35 | 58 | 61 | HD | 41 | Mean (KT/D) | 14/12e | 14/13 | 14/13e | 13/13 | 14/12e | |||||||||||||

| Rambod et al. [35] | 51 | 56 | – | >3 | 50 | 48 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 21/19d | 18/21 | 19/18 | 24/25b | 21/20b | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis and on the WL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 47 | 56 | – | 3 | 49 | 58 | D | 42 | Mean (KT/WL) | 52/48 | 60/57 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 54/50 | 63/62 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 49 | 58 | – | 54 | 49 | 60 | D | 36 | Beta- coeeficient | 0.01 | – | – | 0.16d | 0.03 | – | – | −0.001 | 0.04 | 0.22d | 0.18c | |||||||

| Fujisawa, et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 76 | HD | 120 | Mean (KT/WL) | 86/82 | 78/74 | 80/74 | 56/50b | 63/61 | 82/75 | 78/80 | 70/68 | ||||||||||

| Franke et al. [43] | 48 | 62 | – | 56 | 48 | 62 | D | 65 | Mean (KT/WL) | 7/5b | 6/5b | 7/6b | 7/6 | 7/6b | |||||||||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 55 | 63 | – | 234 | 43a | 72 | – | – | Mean (KT/WL) | 6/5f | 5/4f | 5/4f | 6/6 | 5/5 | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients with CKD not receiving RRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 49 | – | CKD 3–5 | Mean (KT/WL) | 91/69f | – | 49/44f | 48/31f | 66/51f | – | – | – | |||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 66 | 68 | CKD 3b | Mean (KT/WL) | 45/43f | 46/48f | |||||||||||||||||

| 68 | 63 | CKD 4–5 | 45/40f | 46/47f | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 56 | 61 | – | 169 | 57 | 61 | CKD 3b–4 | Mean (KT/CKD) | 43/43 | 50/52 | |||||||||||||||||

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL or QLI-DT . | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTRs . | Patients on dialysis/with CKD . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | RRT . | Time on dialysis (months) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV/FAM . | Total . | ||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | – | 55 | – | 3 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35b | 72/50b | 42/30 | 78/46 | 45/28 | 45/44 | 58/49 | 70/59 | 65/47 | 64/61 | 85/66b | 76/54b | 48/30b | |||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 45/38b | 72/52b | 42/36 | 78/66 | 45/42 | 45/50 | 58/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 64/50 | 85/74b | 77/65b | 48/54b | |||||||||||

| 12 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | 46/35b | 76/50b | 50/30 | 67/46 | 44/28b | 44/44 | 56/49b | 70/59 | 65/48 | 63/61 | 83/66b | 78/54b | 56/30b | ||||||||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 46/38b | 76/52b | 50/36 | 67/66 | 44/42 | 44/50 | 56/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 63/50 | 83/74 | 79/65 | 53/54b | |||||||||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 33 | 65 | 70 | 41 | 47 | 72 | HD | 46 | Mean (KT/D) | 69/56 | 43/41 | 64/63 | 50/40 | 68/56g | 58/63 | 46/30 | 66/58 | ||||||||||

| 46 | 61 | PD | 35 | 69/56 | 43/39 | 64/66 | 50/41 | 68/52g | 58/56 | 46/46 | 66/61 | ||||||||||||||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 34 | 78 | 100 | 39a | – | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 80/68d | 74/35d | 72/62d | 67/40d | 64/46d | 75/55d | 77/42d | 72/59d | ||||||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 52 | 60 | 100 | 47a | 53 | 48 | HD | – | Mean (KT/D) | 47/23c | 46/20c | 49/43c | 45/40c | 51/41c | 49/38c | 48/35c | 52/49c | ||||||||||

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 69 | HD | 92 | Mean (KT/D) | 86/82 | 78/64b | 80/67b | 56/52 | 63/58 | 82/74b | 78/70 | 70/69 | ||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 69 | 65 | D | >12 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35d | 46/40d | ||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 43 | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 91/37f | 30/0f | 69/30f | 48/21f | – | 66/40f | 70/24f | 33/0f | 56/41f | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 39 | 75 | – | >6 | 44 | 75 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 13/11d | 14/11d | 14/13b | 12/11c | 13/11d | |||||||||||||

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 41 | 70 | – | 72%: 3–24h | 46 | 68 | HD | 76%: 3–24h | Mean (KT/D) | 70/49d | 69/52d | 69/58d | 60/56d | 267/215d | |||||||||||||

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | 43 | 52 | – | 35 | 58 | 61 | HD | 41 | Mean (KT/D) | 14/12e | 14/13 | 14/13e | 13/13 | 14/12e | |||||||||||||

| Rambod et al. [35] | 51 | 56 | – | >3 | 50 | 48 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 21/19d | 18/21 | 19/18 | 24/25b | 21/20b | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis and on the WL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 47 | 56 | – | 3 | 49 | 58 | D | 42 | Mean (KT/WL) | 52/48 | 60/57 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 54/50 | 63/62 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 49 | 58 | – | 54 | 49 | 60 | D | 36 | Beta- coeeficient | 0.01 | – | – | 0.16d | 0.03 | – | – | −0.001 | 0.04 | 0.22d | 0.18c | |||||||

| Fujisawa, et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 76 | HD | 120 | Mean (KT/WL) | 86/82 | 78/74 | 80/74 | 56/50b | 63/61 | 82/75 | 78/80 | 70/68 | ||||||||||

| Franke et al. [43] | 48 | 62 | – | 56 | 48 | 62 | D | 65 | Mean (KT/WL) | 7/5b | 6/5b | 7/6b | 7/6 | 7/6b | |||||||||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 55 | 63 | – | 234 | 43a | 72 | – | – | Mean (KT/WL) | 6/5f | 5/4f | 5/4f | 6/6 | 5/5 | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients with CKD not receiving RRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 49 | – | CKD 3–5 | Mean (KT/WL) | 91/69f | – | 49/44f | 48/31f | 66/51f | – | – | – | |||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 66 | 68 | CKD 3b | Mean (KT/WL) | 45/43f | 46/48f | |||||||||||||||||

| 68 | 63 | CKD 4–5 | 45/40f | 46/47f | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 56 | 61 | – | 169 | 57 | 61 | CKD 3b–4 | Mean (KT/CKD) | 43/43 | 50/52 | |||||||||||||||||

Continuous variables are presented as the mean if not otherwise indicated. HRQOL results are presented in bold if they were reportedly significant according to statistical testing (P < 0.05). –, not reported; D, dialysis; S, symptom. aValues presented as median. bP < 0.05. cP < 0.01. dP < 0.001. eP < 0.0001. fP-value not reported. gStatistical test conducted for comparison across more than two groups (KTRs, HD and PD) and P < 0.05. hPercentage within the indicated range.

HRQOL of KTRs compared with patients on dialysis (n = 11), patients on the WL (n = 5) and patients with CKD not receiving RRT (n = 3)

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL or QLI-DT . | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTRs . | Patients on dialysis/with CKD . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | RRT . | Time on dialysis (months) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV/FAM . | Total . | ||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | – | 55 | – | 3 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35b | 72/50b | 42/30 | 78/46 | 45/28 | 45/44 | 58/49 | 70/59 | 65/47 | 64/61 | 85/66b | 76/54b | 48/30b | |||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 45/38b | 72/52b | 42/36 | 78/66 | 45/42 | 45/50 | 58/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 64/50 | 85/74b | 77/65b | 48/54b | |||||||||||

| 12 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | 46/35b | 76/50b | 50/30 | 67/46 | 44/28b | 44/44 | 56/49b | 70/59 | 65/48 | 63/61 | 83/66b | 78/54b | 56/30b | ||||||||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 46/38b | 76/52b | 50/36 | 67/66 | 44/42 | 44/50 | 56/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 63/50 | 83/74 | 79/65 | 53/54b | |||||||||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 33 | 65 | 70 | 41 | 47 | 72 | HD | 46 | Mean (KT/D) | 69/56 | 43/41 | 64/63 | 50/40 | 68/56g | 58/63 | 46/30 | 66/58 | ||||||||||

| 46 | 61 | PD | 35 | 69/56 | 43/39 | 64/66 | 50/41 | 68/52g | 58/56 | 46/46 | 66/61 | ||||||||||||||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 34 | 78 | 100 | 39a | – | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 80/68d | 74/35d | 72/62d | 67/40d | 64/46d | 75/55d | 77/42d | 72/59d | ||||||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 52 | 60 | 100 | 47a | 53 | 48 | HD | – | Mean (KT/D) | 47/23c | 46/20c | 49/43c | 45/40c | 51/41c | 49/38c | 48/35c | 52/49c | ||||||||||

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 69 | HD | 92 | Mean (KT/D) | 86/82 | 78/64b | 80/67b | 56/52 | 63/58 | 82/74b | 78/70 | 70/69 | ||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 69 | 65 | D | >12 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35d | 46/40d | ||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 43 | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 91/37f | 30/0f | 69/30f | 48/21f | – | 66/40f | 70/24f | 33/0f | 56/41f | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 39 | 75 | – | >6 | 44 | 75 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 13/11d | 14/11d | 14/13b | 12/11c | 13/11d | |||||||||||||

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 41 | 70 | – | 72%: 3–24h | 46 | 68 | HD | 76%: 3–24h | Mean (KT/D) | 70/49d | 69/52d | 69/58d | 60/56d | 267/215d | |||||||||||||

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | 43 | 52 | – | 35 | 58 | 61 | HD | 41 | Mean (KT/D) | 14/12e | 14/13 | 14/13e | 13/13 | 14/12e | |||||||||||||

| Rambod et al. [35] | 51 | 56 | – | >3 | 50 | 48 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 21/19d | 18/21 | 19/18 | 24/25b | 21/20b | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis and on the WL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 47 | 56 | – | 3 | 49 | 58 | D | 42 | Mean (KT/WL) | 52/48 | 60/57 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 54/50 | 63/62 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 49 | 58 | – | 54 | 49 | 60 | D | 36 | Beta- coeeficient | 0.01 | – | – | 0.16d | 0.03 | – | – | −0.001 | 0.04 | 0.22d | 0.18c | |||||||

| Fujisawa, et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 76 | HD | 120 | Mean (KT/WL) | 86/82 | 78/74 | 80/74 | 56/50b | 63/61 | 82/75 | 78/80 | 70/68 | ||||||||||

| Franke et al. [43] | 48 | 62 | – | 56 | 48 | 62 | D | 65 | Mean (KT/WL) | 7/5b | 6/5b | 7/6b | 7/6 | 7/6b | |||||||||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 55 | 63 | – | 234 | 43a | 72 | – | – | Mean (KT/WL) | 6/5f | 5/4f | 5/4f | 6/6 | 5/5 | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients with CKD not receiving RRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 49 | – | CKD 3–5 | Mean (KT/WL) | 91/69f | – | 49/44f | 48/31f | 66/51f | – | – | – | |||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 66 | 68 | CKD 3b | Mean (KT/WL) | 45/43f | 46/48f | |||||||||||||||||

| 68 | 63 | CKD 4–5 | 45/40f | 46/47f | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 56 | 61 | – | 169 | 57 | 61 | CKD 3b–4 | Mean (KT/CKD) | 43/43 | 50/52 | |||||||||||||||||

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 and KDQOL . | HRQOL using WHOQOL or QLI-DT . | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTRs . | Patients on dialysis/with CKD . | Physical . | Mental . | Disease-specific . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | RRT . | Time on dialysis (months) . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | S . | EKD . | BKD . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV/FAM . | Total . | ||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Czyzewski et al. [37] | – | 55 | – | 3 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35b | 72/50b | 42/30 | 78/46 | 45/28 | 45/44 | 58/49 | 70/59 | 65/47 | 64/61 | 85/66b | 76/54b | 48/30b | |||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 45/38b | 72/52b | 42/36 | 78/66 | 45/42 | 45/50 | 58/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 64/50 | 85/74b | 77/65b | 48/54b | |||||||||||

| 12 | – | 58 | HD | 78 | 46/35b | 76/50b | 50/30 | 67/46 | 44/28b | 44/44 | 56/49b | 70/59 | 65/48 | 63/61 | 83/66b | 78/54b | 56/30b | ||||||||||

| – | 50 | PD | 40 | 46/38b | 76/52b | 50/36 | 67/66 | 44/42 | 44/50 | 56/68 | 70/74 | 65/74 | 63/50 | 83/74 | 79/65 | 53/54b | |||||||||||

| Sayin et al. [33] | 33 | 65 | 70 | 41 | 47 | 72 | HD | 46 | Mean (KT/D) | 69/56 | 43/41 | 64/63 | 50/40 | 68/56g | 58/63 | 46/30 | 66/58 | ||||||||||

| 46 | 61 | PD | 35 | 69/56 | 43/39 | 64/66 | 50/41 | 68/52g | 58/56 | 46/46 | 66/61 | ||||||||||||||||

| Zheng et al. [38] | 34 | 78 | 100 | 39a | – | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 80/68d | 74/35d | 72/62d | 67/40d | 64/46d | 75/55d | 77/42d | 72/59d | ||||||||||

| Tamura et al. [34] | 52 | 60 | 100 | 47a | 53 | 48 | HD | – | Mean (KT/D) | 47/23c | 46/20c | 49/43c | 45/40c | 51/41c | 49/38c | 48/35c | 52/49c | ||||||||||

| Fujisawa et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 69 | HD | 92 | Mean (KT/D) | 86/82 | 78/64b | 80/67b | 56/52 | 63/58 | 82/74b | 78/70 | 70/69 | ||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 69 | 65 | D | >12 | Mean (KT/D) | 45/35d | 46/40d | ||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 43 | – | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 91/37f | 30/0f | 69/30f | 48/21f | – | 66/40f | 70/24f | 33/0f | 56/41f | |||||||||

| Ranabhat et al. [30] | 39 | 75 | – | >6 | 44 | 75 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 13/11d | 14/11d | 14/13b | 12/11c | 13/11d | |||||||||||||

| Sapkota et al. [36] | 41 | 70 | – | 72%: 3–24h | 46 | 68 | HD | 76%: 3–24h | Mean (KT/D) | 70/49d | 69/52d | 69/58d | 60/56d | 267/215d | |||||||||||||

| Tomasz and Piotr [31] | 43 | 52 | – | 35 | 58 | 61 | HD | 41 | Mean (KT/D) | 14/12e | 14/13 | 14/13e | 13/13 | 14/12e | |||||||||||||

| Rambod et al. [35] | 51 | 56 | – | >3 | 50 | 48 | HD | >3 | Mean (KT/D) | 21/19d | 18/21 | 19/18 | 24/25b | 21/20b | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients on dialysis and on the WL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rosenberger et al. [41] | 47 | 56 | – | 3 | 49 | 58 | D | 42 | Mean (KT/WL) | 52/48 | 60/57 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 54/50 | 63/62 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kovacs et al. [42] | 49 | 58 | – | 54 | 49 | 60 | D | 36 | Beta- coeeficient | 0.01 | – | – | 0.16d | 0.03 | – | – | −0.001 | 0.04 | 0.22d | 0.18c | |||||||

| Fujisawa, et al. [32] | 44 | 43 | 74 | 126 | 46 | 76 | HD | 120 | Mean (KT/WL) | 86/82 | 78/74 | 80/74 | 56/50b | 63/61 | 82/75 | 78/80 | 70/68 | ||||||||||

| Franke et al. [43] | 48 | 62 | – | 56 | 48 | 62 | D | 65 | Mean (KT/WL) | 7/5b | 6/5b | 7/6b | 7/6 | 7/6b | |||||||||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 55 | 63 | – | 234 | 43a | 72 | – | – | Mean (KT/WL) | 6/5f | 5/4f | 5/4f | 6/6 | 5/5 | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus patients with CKD not receiving RRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 49 | – | CKD 3–5 | Mean (KT/WL) | 91/69f | – | 49/44f | 48/31f | 66/51f | – | – | – | |||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 66 | 68 | CKD 3b | Mean (KT/WL) | 45/43f | 46/48f | |||||||||||||||||

| 68 | 63 | CKD 4–5 | 45/40f | 46/47f | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 56 | 61 | – | 169 | 57 | 61 | CKD 3b–4 | Mean (KT/CKD) | 43/43 | 50/52 | |||||||||||||||||

Continuous variables are presented as the mean if not otherwise indicated. HRQOL results are presented in bold if they were reportedly significant according to statistical testing (P < 0.05). –, not reported; D, dialysis; S, symptom. aValues presented as median. bP < 0.05. cP < 0.01. dP < 0.001. eP < 0.0001. fP-value not reported. gStatistical test conducted for comparison across more than two groups (KTRs, HD and PD) and P < 0.05. hPercentage within the indicated range.

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 . | . | HRQOL using WHOQOL . | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTRs . | . | HC and the GP . | Physical . | . | Mental . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | . | Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV . | Total . | |

| KTRs versus HCs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ay et al. [45] | 32 | 60 | 100 | 3 | 38 | 51 | Mean (KT/HC) | 46/48 | 72/80b | 52/74c | 68/67 | 57/62 | 44/45 | 63/64 | 66/70b | 50/66 | 64/64 | ||||||||

| 9 | 46/48 | 78/80 | 51/74c | 70/67 | 58/62 | 44/45 | 61/64 | 67/70 | 56/66 | 63/64 | |||||||||||||||

| Shrestha, et al. [16] | 39a | 53 | 100 | 46a | 55a | 34 | Mean (KT/HC) | 65/81d | 71/84b | 65/92d | 72/84b | 54/73d | 69/78 | 63/69 | 77/81 | 76/90 | 79/77 | ||||||||

| Taskintuna et al. [46] | 33 | 74 | 100 | 39 | Matched | 80 | Mean (KT/HC) | 73/92b | 54/84d | 69/82c | 53/67c | 63/56 | 70/69 | 51/67 | 64/60 | ||||||||||

| Yagil et al. [47] | 53 | 62 | – | 64 | Matched | Matched | Mean (KT/HC) | 52/88b | 45/82b | 60/80b | 54/68b | 44/62b | 69/83b | 55/90b | 61/74b | ||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 34 | – | Mean (KT/HC) | 91/100 | 30/100 | 69/94 | 48/85 | 66/91 | 70/99 | 33/100 | 56/94 | ||||||||||

| Franke et al. [43] | 48 | 62 | – | 56 | Matched | Matched | Mean (KT/HC) | 7/7 | 7/6 | 6/6 | 7/7 | 7/7 | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus GP from the same country or region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cost-Requena a et al. [56] | 53 | 68 | 19 | 1 | – | – | Mean difference (SD) | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | ||||||||

| 6/12/18 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | |||||||||||||||

| 24 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | |||||||||||||||

| Lonning et al. [28] | 72 | 71 | 21 | 12 | Matched | Male | Mean difference (SD) | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | ||||||||||

| Female | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Zhao et al. [49] | 77%: 18–44g | 72 | – | 62%: 6–12g | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 82/91e | 46/80e | 68/86e | 59/70e | 64/70e | 87/87e | 51/76e | 62/73e | ||||||||||

| Liu et al. [53] | 43 | 62 | 15 | 39 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 80/91e | 63/80e | 71/86e | 52/70e | 66/70e | 71/87e | 72/76e | 73/73 | ||||||||||

| Lippe, et al. [27] | 57 | 66 | – | 40 | Matched | Matched | Mean (KT/GP) | 44/50d | 73/82d | 52/75d | 71/73 | 57/74d | 48/53b | 54/61d | 81/88b | 71/85d | 78/82 | ||||||||

| Cornella et al. [50] | 67 | 64 | – | 41 | Matched | Male | Mean (KT/GP) | 82/84 | – | 18/74b | 37/62b | – | 50/68b | 47/78b | 76/74 | 65/69 | |||||||||

| Female | 63/64 | – | 22/59b | 40/49b | 47/52 | 42/71b | 74/68 | 59/57 | |||||||||||||||||

| Aasebo et al. [51] | 29 | 44 | 66 | 59a | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 49/53d | 87/94d | 74/90d | 76/80 | 60/81d | 49/52d | 56/61d | 80/89d | 76/90d | 77/80c | ||||||||

| Esposito et al. [54] | 52 | 59 | – | 6 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 41/50b | 49/50 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7–60 | 46/50b | 49/50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| >60 | 44/50b | 52/50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 56 | 61 | – | 169 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 43/50d | 50/50d | ||||||||||||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 55 | 63 | – | 234 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 66/84f | 81/81 | 60/75f | 52/72f | 51/61f | 79/83 | 87/81 | 69/75 | ||||||||||

| Wei et al. [55] | 49 | 46 | 4 | 173 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 80/92c | 68/84c | 83/85 | 59/69c | 61/68c | 77/87c | 70/79b | 68/73b | ||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 45 | 47 | Mean (KT/GP) | 45/50d | 46/47d | ||||||||||||||||

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 37 | 51 | 100 | 1.5 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 15/16 | 16/15c | 17/15 | 17/15 | ||||||||||||||

| 12 | 16/16 | 16/15c | 17/15 | 16/15 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Karam et al. [52] | 53 | 53 | – | >120 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | ||||||||||||||||||

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 . | . | HRQOL using WHOQOL . | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTRs . | . | HC and the GP . | Physical . | . | Mental . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | . | Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV . | Total . | |

| KTRs versus HCs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ay et al. [45] | 32 | 60 | 100 | 3 | 38 | 51 | Mean (KT/HC) | 46/48 | 72/80b | 52/74c | 68/67 | 57/62 | 44/45 | 63/64 | 66/70b | 50/66 | 64/64 | ||||||||

| 9 | 46/48 | 78/80 | 51/74c | 70/67 | 58/62 | 44/45 | 61/64 | 67/70 | 56/66 | 63/64 | |||||||||||||||

| Shrestha, et al. [16] | 39a | 53 | 100 | 46a | 55a | 34 | Mean (KT/HC) | 65/81d | 71/84b | 65/92d | 72/84b | 54/73d | 69/78 | 63/69 | 77/81 | 76/90 | 79/77 | ||||||||

| Taskintuna et al. [46] | 33 | 74 | 100 | 39 | Matched | 80 | Mean (KT/HC) | 73/92b | 54/84d | 69/82c | 53/67c | 63/56 | 70/69 | 51/67 | 64/60 | ||||||||||

| Yagil et al. [47] | 53 | 62 | – | 64 | Matched | Matched | Mean (KT/HC) | 52/88b | 45/82b | 60/80b | 54/68b | 44/62b | 69/83b | 55/90b | 61/74b | ||||||||||

| Iqbal et al. [40] | 39 | – | – | >6 | 34 | – | Mean (KT/HC) | 91/100 | 30/100 | 69/94 | 48/85 | 66/91 | 70/99 | 33/100 | 56/94 | ||||||||||

| Franke et al. [43] | 48 | 62 | – | 56 | Matched | Matched | Mean (KT/HC) | 7/7 | 7/6 | 6/6 | 7/7 | 7/7 | |||||||||||||

| KTRs versus GP from the same country or region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cost-Requena a et al. [56] | 53 | 68 | 19 | 1 | – | – | Mean difference (SD) | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | ||||||||

| 6/12/18 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | |||||||||||||||

| 24 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | |||||||||||||||

| Lonning et al. [28] | 72 | 71 | 21 | 12 | Matched | Male | Mean difference (SD) | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | >0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | ||||||||||

| Female | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Zhao et al. [49] | 77%: 18–44g | 72 | – | 62%: 6–12g | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 82/91e | 46/80e | 68/86e | 59/70e | 64/70e | 87/87e | 51/76e | 62/73e | ||||||||||

| Liu et al. [53] | 43 | 62 | 15 | 39 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 80/91e | 63/80e | 71/86e | 52/70e | 66/70e | 71/87e | 72/76e | 73/73 | ||||||||||

| Lippe, et al. [27] | 57 | 66 | – | 40 | Matched | Matched | Mean (KT/GP) | 44/50d | 73/82d | 52/75d | 71/73 | 57/74d | 48/53b | 54/61d | 81/88b | 71/85d | 78/82 | ||||||||

| Cornella et al. [50] | 67 | 64 | – | 41 | Matched | Male | Mean (KT/GP) | 82/84 | – | 18/74b | 37/62b | – | 50/68b | 47/78b | 76/74 | 65/69 | |||||||||

| Female | 63/64 | – | 22/59b | 40/49b | 47/52 | 42/71b | 74/68 | 59/57 | |||||||||||||||||

| Aasebo et al. [51] | 29 | 44 | 66 | 59a | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 49/53d | 87/94d | 74/90d | 76/80 | 60/81d | 49/52d | 56/61d | 80/89d | 76/90d | 77/80c | ||||||||

| Esposito et al. [54] | 52 | 59 | – | 6 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 41/50b | 49/50 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7–60 | 46/50b | 49/50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| >60 | 44/50b | 52/50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stomer et al. [48] | 56 | 61 | – | 169 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 43/50d | 50/50d | ||||||||||||||||

| Neipp et al. [44] | 55 | 63 | – | 234 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 66/84f | 81/81 | 60/75f | 52/72f | 51/61f | 79/83 | 87/81 | 69/75 | ||||||||||

| Wei et al. [55] | 49 | 46 | 4 | 173 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 80/92c | 68/84c | 83/85 | 59/69c | 61/68c | 77/87c | 70/79b | 68/73b | ||||||||||

| Karine et al. [39] | 55 | 61 | – | – | 45 | 47 | Mean (KT/GP) | 45/50d | 46/47d | ||||||||||||||||

| Lumsdaine et al. [29] | 37 | 51 | 100 | 1.5 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | 15/16 | 16/15c | 17/15 | 17/15 | ||||||||||||||

| 12 | 16/16 | 16/15c | 17/15 | 16/15 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Karam et al. [52] | 53 | 53 | – | >120 | – | – | Mean (KT/GP) | ||||||||||||||||||

For the HRQOL results of using the NIDDK-QOL, see notes below the table. Karam et al. reported significantly lower personal function (median 1 versus 4d) and GH (median 6 versus 7c), more physical symptoms (median 10 versus 8d) and more burden caused by physical (median 23 versus 15d) and mental symptoms (median 6 versus 5b). Continuous variables are presented as the mean if not otherwise indicated. HRQOL results are presented in bold if they were reportedly significant according to statistical testing (P < 0.05). –, not reported. aValues presented as the median. bP < 0.05. cP < 0.01. dP < 0.001. eP < 0.0001. fP-value not reported. gPercentage within the indicated range.

| References . | Patient characteristics . | Effect measure . | HRQOL using SF-36 . | . | HRQOL using WHOQOL . | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTRs . | . | HC and the GP . | Physical . | . | Mental . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||||

| Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | LDKT, % . | Time after KT (minutes) . | . | Mean age (years) . | Male, % . | . | PCS . | PF . | RP . | BP . | GH . | . | MCS . | VT . | SF . | RE . | MH . | . | PHY . | PSY . | SOC . | ENV . | Total . | |

| KTRs versus HCs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ay et al. [45] | 32 | 60 | 100 | 3 | 38 | 51 | Mean (KT/HC) | 46/48 | 72/80b | 52/74c | 68/67 | 57/62 | 44/45 | 63/64 | 66/70b | 50/66 | 64/64 | ||||||||

| 9 | 46/48 | 78/80 | 51/74c | 70/67 | 58/62 | 44/45 | 61/64 | 67/70 | 56/66 | 63/64 | |||||||||||||||

| Shrestha, et al. [16] | 39a | 53 | 100 | 46a | 55a | 34 | Mean (KT/HC) | 65/81d | 71/84b | 65/92d | 72/84b | 54/73d | 69/78 | 63/69 | 77/81 | 76/90 | 79/77 | ||||||||

| Taskintuna et al. [46] | 33 | 74 | 100 | 39 | Matched | 80 | Mean (KT/HC) | 73/92b | 54/84d | 69/82c | 53/67c | 63/56 | 70/69 | 51/67 | 64/60 | ||||||||||