-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thomas Le Barbanchon, Julien Sauvagnat, Electoral Competition, Voter Bias, and Women in Politics, Journal of the European Economic Association, Volume 20, Issue 1, February 2022, Pages 352–394, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvab028

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We quantify the implications of voter bias and electoral competition for politicians’ gender composition. Unfavorable voters’ attitudes toward women and local gender earnings gap correlate negatively with the share of female candidates in Parliamentary elections. Using within-candidate variation across the different polling stations of an electoral district in a given election year, we find that female candidates obtain fewer votes in municipalities with higher gender earnings gaps. We show theoretically that when voters are biased against women, parties facing gender quotas select male candidates in the most contestable districts. We find empirical support for such a strategic party response to voter gender bias. Simulating our calibrated model confirms that competition significantly hinders the effectiveness of gender quotas.

1. Introduction

Despite significant progress in recent years, women are still largely under-represented among elected politicians, accounting for around 25% of Members of Parliament (MPs) across the world.1 While recent evidence suggests that female and male politicians tend to support different policy choices,2 there is no consensus on the key factors that drive the under-representation of women in politics. A large body of work has explored whether political parties favor male candidates (see, e.g., Norris and Lovenduski 1995), and recent studies have found mixed empirical evidence on the importance of party bias (Esteve-Volart and Bagues 2012; Casas-Arce and Saiz 2015; Bagues and Campa 2020, 2021). The possibility that women’s access to office might be restricted by voters’ preferences is also highly debated. The main reason for this is probably the difficulty of identifying voter bias in the data. Whether or not voter bias could account for the small share of women in politics therefore remains an open question (see the review in Krook 2018).3 Understanding the causes of women’s under-representation in politics has also important consequences for our knowledge of candidate selection and the quality of those who become politicians (Dal Bó et al. 2017).

In this paper, we quantify the role of voters’ preferences in the gender composition of politicians. We first show empirically that unfavorable voters’ attitudes toward women, measured either through survey data on gender role in politics or through local gender earnings gap, correlate negatively with the share of female candidates in French Parliamentary elections. Using within-candidate variation, we also find that female candidates obtain fewer votes in French municipalities with higher gender earnings gaps within an electoral district in the same election year. Our main theoretical and empirical contribution is then to show that electoral competition hurts women’s representation in politics when voters have a preference for male politicians, and when parties face gender quota on candidates. For this, we propose a model of political selection that sheds light on the trade-offs faced by political parties when policies encouraging gender diversity are introduced. We define as biased in favor of male politicians a voter who is more likely to vote for a male politician than for a female politician, when both politicians have the same ideology and expertise.4 We show that parties facing gender quotas on candidates select men rather than women in contestable districts (i.e., close races), if and only if voters are biased in favor of male candidates. We take this test to the French data and find strong empirical support for a strategic party response to voter bias in favor of male candidates. Finally, we calibrate the model, and show in simulations that electoral competition hinders the effectiveness of gender quotas in boosting women’s presence among elected politicians. The effect is quantitatively large: we find that an increase of 10% in the share of contestable districts reduces the increase in the fraction of elected women due to the introduction of gender quotas by around 25%.

A body of work in political science tests for the existence of a voter gender bias in survey experiments (e.g., Sanbonmatsu 2002; Schwarz, Hunt, and Coppock 2018; Teele, Kalla, and Rosenbluth 2018).5 In the first part of the paper, we follow an alternative strategy and measure the relation between voters’ attitudes toward gender in the field and gender gaps in the composition of candidates running for elections and in electoral outcomes.6 For this, we use both elicited data on gender roles in politics and administrative data on local gender earnings gaps—which for the latter allows us to proxy for differences in attitudes toward gender within the same electoral districts. In doing so, we rely on previous studies showing that (residualized) gender earnings gap reflects traditional or unfavourable views toward women’s role in society (Altonji and Blank 1999; Bertrand 2011).

We find that voters’ attitudes toward gender are strongly associated with the gender distribution of candidates across electoral districts within France, after controlling for a rich set of candidates’ characteristics, such as age, education, past occupation, and eventually political experience. A 10 percentage point increase in the share of respondents who agree with the statement “Men are better political leaders than women” is associated with a 2.3 percentage point decrease in the share of female candidates, a 10% drop from the sample mean. This result is robust to using respondents’ answers from the statement “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” or gender earnings gaps, as alternative proxies for voters’ attitudes. We then exploit the granularity of local gender earnings gaps in order to estimate the effect of voters’ attitudes on gender gaps in vote shares for the same female and male candidates, across municipalities of the same electoral districts in the same election.7 To the best of our knowledge, we provide the first granular analysis filtering out supply factors when estimating the effect of voters’ attitudes on electoral outcomes. We find a positive and strong correlation between gender earnings gaps and electoral gaps across municipalities: a one standard deviation increase in gender earnings gap leads to an increase by 0.6 percentage points in vote shares between male and female candidates. Overall, we find converging evidence that female candidates obtain lower votes in areas with less favorable attitudes toward women, and are less likely to run for elections in these areas.

We hypothesize that these two facts are linked and that parties refrain from selecting female candidates in districts with less favorable attitudes toward women because they anticipate a lower probability of winning elections when female candidates run in these districts. In the second part of the paper, we assess whether this strategic party response to the presence of voter bias accounts quantitatively for the low fraction of elected women, even after the introduction of gender quota on candidates. For this, we build a model of electoral competition (in majoritarian single-member constituency elections) in which political parties select candidates across districts taking into account that voters care about the gender of candidates in their districts. We first show that in the absence of gender quotas, parties always select the best candidate from each district—that is, the one who maximizes the probability of winning the election whatever the degree of political contestability. However, electoral competition shapes the selection of male versus female candidates in the presence of gender quotas on candidates. In that case, we show that parties strategically select men in contestable districts (i.e., close races) and women in non-contestable districts when voters are biased in favor of male candidates.

We take this prediction to the data and exploit the introduction in 2000 of gender quotas in French Parliamentary elections (referred to as the Parity Law), in which parties face fines when they deviate from a 50% national gender parity rule on candidates.8 We find strong empirical support for a strategic party behavior and the existence of a voter bias in favor of male candidates in French elections: while electoral competition has no effect on the gender allocation of candidates before 2000, we find that parties are more likely to select male candidates in contestable districts after the introduction of gender quotas.

Finally, we quantify the importance of voter bias and electoral competition in restricting women’s representation in politics. In our calibrated model, the fraction of female candidates pre-quota is 8%, in line with the data. When we introduce the parity rule in the model, we find that the electoral cost of selecting women when there is a voter bias in favor of male candidates outweighs the cost of the fine in the most contestable districts. This force is large enough for explaining why the main two parties select post-quota only 35% of female candidates, significantly below the objective of the Parity Law. We then conduct counterfactual simulations and confirm that an increase in competition would further significantly reduce the share of women elected in the Parliament.

Importantly, our results do not imply that intrinsic party bias—whereby political parties prefer male politicians per se—does not explain part of the low fraction of female politicians. Instead, we argue that voter gender bias generates a strategic party bias, which also matters quantitatively for understanding the under-representation of women in politics. To fix ideas, we propose an extension of our model that features both voter gender bias and intrinsic party bias in favor of male politicians. We show that parties with intrinsic preferences about politicians’ gender still refrain from selecting female candidates in the most contestable districts when facing gender quotas and voter gender bias. Simulation of this extension of the model confirms that electoral competition dampens significantly the effectiveness of gender quotas even in the presence of an intrinsic party bias.

This paper contributes to several strands of the literature. It first relates to a growing body of work on political competition and political selection. Prior empirical studies highlight the effect of political competition on accountability (Ferraz and Finan 2011), on the quality of politicians (De Paola and Scoppa 2011; Galasso and Nannicini 2011), on policy choices (Besley and Preston 2007; Stromberg 2008; Besley, Persson, and Sturm 2010), and on the transmission of political power within dynasties (Dal Bó et al. 2009). Folke and Rickne (2016) and Esteve-Volart and Bagues (2012) provide empirical evidence that electoral competition improves women’s position on the ballots of closed-list elections. We build on Galasso and Nannicini (2011)’s framework and provide the first formal model of electoral competition that incorporates voters’ preferences for politicians’ gender. We use the model to show that electoral competition harms women’s representation in French Parliamentary single-member district majority rule elections.9

We also contribute to the literature on the effect of gender quotas in politics,10 which is based on reduced-form evidence from several reforms. Gender quotas have been shown to affect the quality of politicians running for office (Baltrunaite et al. 2014; O’Brien and Rickne 2016; Besley et al. 2017), the type of policies implemented (Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004; Baltrunaite et al. 2016), and beliefs about female leader effectiveness (Beaman et al. 2009; Paola et al. 2010). Another strand of the literature studies politicians’ incentives for voting in favor of the adoption of gender quotas. In that vein, Fréchette et al. (2008) propose as an explanation for the vote in favor of the 2000 Parity Law by the French Parliament a theory in which (male) incumbent politicians find it in their best interests to support the introduction of gender quotas when there is a voter bias in favor of male candidates: in doing so, they increase the probability of running against a woman and being reelected in the following election. Murray, Krook, and Opello (2012) offers an alternative view emphasizing the role of party pragmatism in passing the French Parity Law. Our study shifts the focus on the role of voter gender bias for understanding the consequences of gender quotas for parties’ political selection. Moreover, beyond reduced-form studies, our model allows us to conduct counterfactuals on the effect of gender quotas in boosting women’s representation among elected politicians depending on the degree of political competition.

More broadly, we also relate to the literature on the influence of social norms on economic and political outcomes. A few papers (Fernández, Fogli, and Olivetti 2004; Fortin 2005; Fernández and Fogli 2009; Alesina, Giuliano, and Nunn 2013) show how gender role attitudes influence gender gaps in labor market outcomes. In politics, Gagliarducci and Paserman (2012) find that the probability of early termination for elected female mayors in Italy is higher in regions with less favorable attitudes toward working women. Our finding that voters’ attitudes toward gender affect gender gaps in politics—both for differences in electoral scores and in the gender composition of candidates—has important consequences, and overall suggests that slow-moving voters’ attitudes might be an important factor that limits convergence toward a gender parity among politicians.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present French institutions and our data. In Section 3, we show how local differences in voters’ attitudes toward gender relate to the gender distribution of candidates across districts, and to gender gaps in electoral outcomes. We present our model of political selection with voter gender bias in Section 4, and take it to the data in Section 5. In Section 6, we run counterfactual simulations on the effect of gender quotas depending on the degree of political competition. Section 7 concludes.

2. Institutions and Data

2.1. French Institutions and Parliamentary Elections

The lower house of the French Parliament, the Assemblée Nationale, is composed of 577 members elected for 5 years (single-member constituencies), according to a two-round plurality voting rule.11 In every district, candidates compete in a first round. If no candidate obtains more than 50% of votes (and 25% of registered citizens), a runoff is set with candidates selected by more than 12.5% of registered citizens in round 1 (Pons and Tricaud 2018). The candidate with the most votes in the runoff wins the election. In practice, a vast majority of runoffs occur between two candidates, often with one candidate from the Right and one candidate from the Left.

We gather data for the last seven Parliamentary elections: 1988, 1993, 1997, 2002, 2007, 2012, and 2017.12 Our main empirical analysis focuses on candidates from the two main party coalitions: the Left coalition and the Right coalition.13 These two coalitions account for around 80% of elected MPs over the sample period.14 Their candidates have on average an ex-ante probability of being elected equal to 43%. By contrast, candidates from other parties have on average very low chances of winning a seat in the Parliament (i.e., around 1.5% in our sample).15 Given our focus on parties’ selection of candidates in a context of electoral competition, we exclude the other parties from our sample.

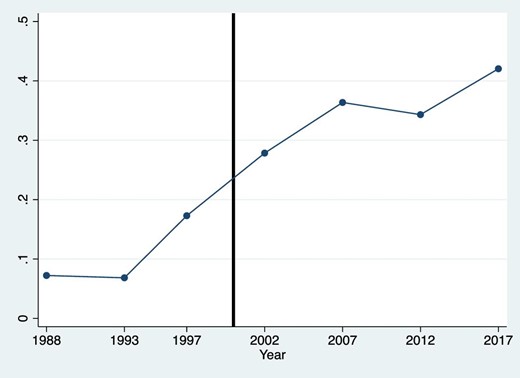

Figure 1 presents the share of female candidates in French Parliamentary elections over the last three decades. The share of female candidates hovers around 10% in the 1980s and 1990s, then almost doubles between the 1990s’ and the 2000s’ elections, and ranges between 35% and 40% in the last two elections in 2012 and 2017. This increase (at least partially) follows the introduction of gender quotas on candidates in French Parliamentary elections with the vote of the Parity Law in 2000, which we describe below.

Fraction of women among candidates to French Parliamentary elections. The sample covers all candidates running for the two main Left and Right party coalitions.

The 2000 Parity Law

The Parity Law voted in 2000 stipulates that each party should have an equal fraction of male and female candidates across electoral districts in Parliamentary elections. When the difference between female and male candidates exceeds 4% (below 48% or above 52%), non-compliance with the 50% parity rule results in a financial penalty computed as follows: public funding provided to political parties based on the number of votes they receive in the first round of elections is reduced “by a percentage equivalent to one half of the difference between the total number of candidates of each sex, out of the total number of candidates”.16 As discussed in more details below, the 2000 Parity Law in French Parliamentary elections provides us with a unique laboratory for testing the presence of voter gender bias.

2.2. Data Sources and Variables

We use data from several sources: (i) administrative and web data on candidates and electoral outcomes; (ii) survey data on voters’ attitude toward gender; and (iii) administrative and census data on earnings and voters’ demographics across municipalities and electoral districts.

It is crucial for the analysis presented below to (at least) observe the gender of candidates, their party affiliation, as well as granular information on their electoral scores. We also gather data on other candidates’ characteristics that we use as control variables in the regressions presented below, such as age, education, occupation, and past political experience.

Candidates and Electoral Outcomes

The French Ministry of Interior has been publishing vote shares for each candidate, along with their gender and party affiliation, for Parliamentary (and Presidential) elections (at the electoral district level) since 1988.17 Vote shares are also available at the municipality level (within electoral districts) starting in 1993. The Ministry of Interior has also been providing information on candidates’ date of birth and occupation since 2012. We fill in missing information on date of birth and occupation in elections prior to 2012 using information from other sources.18 We then construct a dummy for high-skill occupations, such as managers, engineers, physicians, lawyers, and university professors.19 We also match candidates with the list of all members of government (from the fifth Republic starting in 1958), and we code whether candidates are alumni of an elite university, defined as graduates from the following list of French elite institutions: Ecole Polytechnique and Ecole Centrale Paris (for engineers), Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA, for public administration), Ecole des Hautes Études Commerciales (HEC, for business), and SciencesPo (for politicians).20 Finally, starting from the 2002 election, we construct a dummy for candidates with a local mandate, which equals 1 if the candidate has been elected as mayor or in the municipality council in the same electoral district where she/he runs for Parliamentary election.

We also rely on the timing of French elections—where Parliamentary elections are in the wake of Presidential elections since 2002—, and compute as a control for ideology/party popularity in each district the vote share that each party obtains in the previous Presidential election in the same electoral district. This also provides us with a measure of electoral contestability for each district. Specifically, we define as contestable districts for which the vote margin between the Left and the Right parties in the previous Presidential election was between −3 and +3 percentage points. We provide in Section 5 evidence on the predictive power of this measure. Importantly, this measure is gender-neutral as the Presidential candidates of the main parties are male, except in 2007 when Ségolène Royal ran from the Left party.

Proxies for Voters’ Attitudes

Our empirical analysis exploits the sizeable geographical differences in attitudes toward women across areas in France. Specifically, the analysis presented below relies on the Generation Gender Surveys (GGSs) that compile individual-level surveys on a variety of topics, including attitudes and preferences on gender roles in politics and in labor markets. The French wave of the GGS surveyed around 10,000 households in 2006. The survey is designed to be well-distributed geographically.

We follow Alesina, Giuliano, and Nunn (2013) and examine two questions that quantify individuals’ attitudes about gender roles. Using the GGS, we construct the share of respondents at the département level (the finest geographical unit available in the GGS)21 who separately agree with the following two statements: “On the whole, men are better political leaders than women” and “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women”. The respondents are asked to choose among “strongly agree”, “agree”, “disagree”, “strongly disagree”, and “neither agree nor disagree”. As in Alesina, Giuliano, and Nunn (2013), we omit observations for which the respondents answered “neither agree nor disagree”, and compute for each département the average of respondents that answered “agree” or “strongly agree”.22

Unfortunately, this measure does not provide us with cross-sectional variation in voters’ attitudes toward gender within electoral districts, which would allow us to estimate the effect of voters’ attitudes on electoral scores of male versus female candidates keeping constant the supply of candidates. For this, we compute local gender earnings gap from the French employment registers [Déclarations Annuelles des Données Sociales (DADS)] as an alternative—and more granular—proxy for voters’ attitudes. The data are based on a mandatory employer report of the gross yearly earnings of each employee subject to French payroll taxes, and include all employed individuals. For our main analysis, we compute residualized local earnings gaps in order to absorb differences across municipalities related to local distributions of workers’ age and occupation, and of employers’ industry. In doing so, we rely on a large body of literature showing that residualized gender earnings gap reflects attitudes toward gender in labor markets (Altonji and Blank 1999; Bertrand 2011), and more generally on the role of women in society. However, differential selection into occupation by gender may also reflect gender attitudes. Therefore, we will also assess below the robustness of our results when using raw gender earnings gap.

We average gender earnings gaps either at the municipality level or at the broader electoral district level, in the year preceding each Parliamentary election.23

Summary Statistics

Table 1 presents summary statistics of our main sample, which consists of 7,038 candidate × election observations spanning seven Parliamentary elections in France from 1988 to 2017. We also present in Online Appendix Table A.1 the mean and standard deviation of the variables separately for male and female candidates.

| . | Observations . | Mean . | SD . | p1 . | p50 . | p99 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: candidates characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 7,038 | 0.240 | 0.427 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 6,376 | 51.508 | 9.937 | 28.000 | 52.000 | 73.000 |

| Elite university education | 7,038 | 0.134 | 0.341 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| High-skill occupation | 6,084 | 0.530 | 0.499 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| First-time candidate | 7,038 | 0.366 | 0.482 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Incumbent | 7,038 | 0.314 | 0.464 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Former government member | 7,038 | 0.080 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Local mandate (from 2002 election) | 3,880 | 0.623 | 0.485 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel B: elections characteristics | ||||||

| Vote share (round 1) | 7,038 | 0.301 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.302 | 0.587 |

| Candidate elected | 7,038 | 0.429 | 0.495 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Presidential party vote share | 7,038 | 0.237 | 0.084 | 0.048 | 0.229 | 0.436 |

| Contestable district | 7,038 | 0.290 | 0.454 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel C: voters’ attitudes | ||||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | 6,989 | 0.167 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.312 |

| Men more right to a job: % agree | 6,989 | 0.278 | 0.088 | 0.123 | 0.278 | 0.481 |

| Gender earnings gap (residualized) | 7,038 | 0.125 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.128 | 0.224 |

| . | Observations . | Mean . | SD . | p1 . | p50 . | p99 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: candidates characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 7,038 | 0.240 | 0.427 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 6,376 | 51.508 | 9.937 | 28.000 | 52.000 | 73.000 |

| Elite university education | 7,038 | 0.134 | 0.341 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| High-skill occupation | 6,084 | 0.530 | 0.499 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| First-time candidate | 7,038 | 0.366 | 0.482 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Incumbent | 7,038 | 0.314 | 0.464 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Former government member | 7,038 | 0.080 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Local mandate (from 2002 election) | 3,880 | 0.623 | 0.485 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel B: elections characteristics | ||||||

| Vote share (round 1) | 7,038 | 0.301 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.302 | 0.587 |

| Candidate elected | 7,038 | 0.429 | 0.495 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Presidential party vote share | 7,038 | 0.237 | 0.084 | 0.048 | 0.229 | 0.436 |

| Contestable district | 7,038 | 0.290 | 0.454 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel C: voters’ attitudes | ||||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | 6,989 | 0.167 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.312 |

| Men more right to a job: % agree | 6,989 | 0.278 | 0.088 | 0.123 | 0.278 | 0.481 |

| Gender earnings gap (residualized) | 7,038 | 0.125 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.128 | 0.224 |

Notes: This table presents the summary statistics for our sample, which consists of 7,038 candidate–district observations over seven Parliamentary elections between 1988 and 2017. There are 3,890 unique candidates in this sample. A candidate is included in the sample if she/he is running for the Left or Right coalition in a given election. Female is a dummy if the candidate is a woman. Age is the age of the candidate at the time of the election. Elite university education is a dummy for graduates of the following list of French elite institutions: Ecole Polytechnique, Ecole Centrale Paris, Ecole Nationale d’Administration, Ecole des Hautes Études Commerciales, and SciencesPo. High-skill occupation is a dummy indicating whether the candidate was either a manager, engineer, physician, lawyer, or university professor. First-time candidate is a dummy indicating whether the candidate is running in a Parliamentary election for the first time. Incumbent is a dummy if the candidate has been elected in the previous Parliamentary election in the same district. Former government member is a dummy indicating whether the candidate has been a member of a former government. Local mandate is a dummy indicating whether the candidate has been elected either as mayor or in the council of a municipality in the same Parliamentary district (available only from 2002). Vote share is the number of votes obtained by the candidate in the first round of a given Parliamentary election over the total number of votes in the same district and election. Candidate elected is a dummy for the candidate winning the election in the district. Presidential party vote share is the vote share obtained by the candidate’s party in the previous Presidential election. Contestable district is a dummy, which equals 1 if the vote margin between the Left and the Right parties in the runoff of the previous Presidential election was between −3 and +3 percentage points (respectively, in the first round of the previous Presidential election for the 2002 and 2017 Presidential elections). Men better political leaders: % agree and Men more right to a job: % agree are drawn from the 2006 GGS, and are computed at the département level. Gender gap in earnings is the average residualized gender gap (between men and women) in the district in the year preceding the election.

| . | Observations . | Mean . | SD . | p1 . | p50 . | p99 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: candidates characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 7,038 | 0.240 | 0.427 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 6,376 | 51.508 | 9.937 | 28.000 | 52.000 | 73.000 |

| Elite university education | 7,038 | 0.134 | 0.341 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| High-skill occupation | 6,084 | 0.530 | 0.499 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| First-time candidate | 7,038 | 0.366 | 0.482 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Incumbent | 7,038 | 0.314 | 0.464 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Former government member | 7,038 | 0.080 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Local mandate (from 2002 election) | 3,880 | 0.623 | 0.485 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel B: elections characteristics | ||||||

| Vote share (round 1) | 7,038 | 0.301 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.302 | 0.587 |

| Candidate elected | 7,038 | 0.429 | 0.495 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Presidential party vote share | 7,038 | 0.237 | 0.084 | 0.048 | 0.229 | 0.436 |

| Contestable district | 7,038 | 0.290 | 0.454 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel C: voters’ attitudes | ||||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | 6,989 | 0.167 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.312 |

| Men more right to a job: % agree | 6,989 | 0.278 | 0.088 | 0.123 | 0.278 | 0.481 |

| Gender earnings gap (residualized) | 7,038 | 0.125 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.128 | 0.224 |

| . | Observations . | Mean . | SD . | p1 . | p50 . | p99 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: candidates characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 7,038 | 0.240 | 0.427 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 6,376 | 51.508 | 9.937 | 28.000 | 52.000 | 73.000 |

| Elite university education | 7,038 | 0.134 | 0.341 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| High-skill occupation | 6,084 | 0.530 | 0.499 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| First-time candidate | 7,038 | 0.366 | 0.482 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Incumbent | 7,038 | 0.314 | 0.464 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Former government member | 7,038 | 0.080 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Local mandate (from 2002 election) | 3,880 | 0.623 | 0.485 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel B: elections characteristics | ||||||

| Vote share (round 1) | 7,038 | 0.301 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.302 | 0.587 |

| Candidate elected | 7,038 | 0.429 | 0.495 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Presidential party vote share | 7,038 | 0.237 | 0.084 | 0.048 | 0.229 | 0.436 |

| Contestable district | 7,038 | 0.290 | 0.454 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel C: voters’ attitudes | ||||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | 6,989 | 0.167 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.312 |

| Men more right to a job: % agree | 6,989 | 0.278 | 0.088 | 0.123 | 0.278 | 0.481 |

| Gender earnings gap (residualized) | 7,038 | 0.125 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.128 | 0.224 |

Notes: This table presents the summary statistics for our sample, which consists of 7,038 candidate–district observations over seven Parliamentary elections between 1988 and 2017. There are 3,890 unique candidates in this sample. A candidate is included in the sample if she/he is running for the Left or Right coalition in a given election. Female is a dummy if the candidate is a woman. Age is the age of the candidate at the time of the election. Elite university education is a dummy for graduates of the following list of French elite institutions: Ecole Polytechnique, Ecole Centrale Paris, Ecole Nationale d’Administration, Ecole des Hautes Études Commerciales, and SciencesPo. High-skill occupation is a dummy indicating whether the candidate was either a manager, engineer, physician, lawyer, or university professor. First-time candidate is a dummy indicating whether the candidate is running in a Parliamentary election for the first time. Incumbent is a dummy if the candidate has been elected in the previous Parliamentary election in the same district. Former government member is a dummy indicating whether the candidate has been a member of a former government. Local mandate is a dummy indicating whether the candidate has been elected either as mayor or in the council of a municipality in the same Parliamentary district (available only from 2002). Vote share is the number of votes obtained by the candidate in the first round of a given Parliamentary election over the total number of votes in the same district and election. Candidate elected is a dummy for the candidate winning the election in the district. Presidential party vote share is the vote share obtained by the candidate’s party in the previous Presidential election. Contestable district is a dummy, which equals 1 if the vote margin between the Left and the Right parties in the runoff of the previous Presidential election was between −3 and +3 percentage points (respectively, in the first round of the previous Presidential election for the 2002 and 2017 Presidential elections). Men better political leaders: % agree and Men more right to a job: % agree are drawn from the 2006 GGS, and are computed at the département level. Gender gap in earnings is the average residualized gender gap (between men and women) in the district in the year preceding the election.

There are 24% of female candidates, and the average age of candidates is 52 years. A total of 13% are alumni from elite universities, and 53% worked in high-skill occupations. In terms of political experience, 37% of candidates run for the first time, 31% are incumbents in the same district, 8% of candidates were members of a former government (at the time of the election), and 62% hold a local mandate in the same district as where they run for Parliamentary election. We also check that candidates tend to run in the same district across elections: 96% of repeat candidates run in the same district.

Panel B presents electoral outcomes. While there are on average eleven candidates (from all parties) running for election in a given district, Left and Right candidates of the two main parties in our sample capture a disproportionally large fraction of the votes: their (individual) vote share is on average 30% in the first round of the election, and their overall probability of being elected is 43%. Using candidates’ parties’ vote shares in the previous Presidential election, we end up with 29% of electoral districts being classified as (ex-ante) contestable. As shown in Online Appendix Table A.1, female candidates obtain on average lower vote shares and are less likely to be elected in Parliamentary elections.

Panel C presents summary statistics for our measures of voters’ attitudes at the geographical level. What is relevant for our work is the cross-sectional variability of these measures, which is substantial for each of them. Importantly for our approach, we then show in Online Appendix Table A.2 that these measures are strongly correlated between them, both within survey respondents and across geographical areas. We find in columns 1 and 2 a strong and statistically significant correlation between attitudes toward gender in politics and on labor markets at the individual level, measured with respondents’ answers to the statements “On the whole, men are better political leaders than women” and “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” in the GGS. This correlation remains robust after aggregating answers at the département level, as shown in column 3. Finally, we relate earnings gaps with survey data in column 4, and find a large and statistically significant correlation between local gender earnings gaps and voters’ attitudes in the GGS: Namely, a one standard-deviation increase in local earnings gap accounts for 46% of the standard deviation in the local share of individuals who agree with the statement “On the whole, men are better political leaders than women”.

3. Voters’ Attitudes and Gender Electoral Gaps: Reduced-Form Evidence

In this section, we provide reduced-form evidence on the importance of voters’ attitudes for (i) the share of women candidates in French Parliamentary elections; and (ii) gender electoral gaps—defined as the difference in vote shares between male and female candidates. We measure geographical differences in voters’ attitudes using both survey data aggregated at the département level and local gender earnings gaps, either at the electoral district or at the municipal level. These measures are increasing with the degree of unfavorable attitudes toward women.

3.1. Voters’ Attitudes and Selection of Male/Female Candidates

Table 2 reports the estimates of our parameter of interest β separately for our three proxies for voters’ attitudes.24 In panel A, we proxy for unfavorable attitudes toward women with the share of agreement with the statement “Men are better political leaders than women”. The coefficient is negative, statistically significant, and stable across specifications. The effect is also economically significant: a 10 percentage point increase in the share of respondents considering that “Men are better political leaders than women” is associated with at least a 2.3 percentage point decrease in the probability that the candidate is a woman, a 10% decrease compared to the 24% sample mean of female candidates. The estimate hardly changes when we further control for candidates’ age, education, and previous occupation, in column (2), and for political experience in column (3). We control for political experience using dummies for incumbents, for candidates running for a Parliamentary election for the first time, for former members of government, and for holding a local mandate. Although these controls are potentially endogenous—for example, being the incumbent is a past outcome—, we find robust results. Finally, we further control in column (4) for the vote shares of candidates’ affiliated party obtained in the same electoral district during the previous Presidential election. The coefficient remains large and statistically significant.25

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | −0.228* | −0.269** | −0.267** | −0.301*** | |

| (0.120) | (0.119) | (0.115) | (0.115) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.127 | 0.163 | 0.208 | 0.211 | |

| Panel B: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men more right to a job: % agree | −0.268*** | −0.290*** | −0.299*** | −0.332*** | |

| (0.076) | (0.076) | (0.072) | (0.071) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.129 | 0.165 | 0.210 | 0.214 | |

| Panel C: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Gender earnings gap (district) | −0.473*** | −0.481*** | −0.494*** | −0.525*** | −0.647** |

| (0.158) | (0.159) | (0.152) | (0.152) | (0.273) | |

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 |

| R2 | 0.128 | 0.164 | 0.209 | 0.212 | 0.344 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | −0.228* | −0.269** | −0.267** | −0.301*** | |

| (0.120) | (0.119) | (0.115) | (0.115) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.127 | 0.163 | 0.208 | 0.211 | |

| Panel B: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men more right to a job: % agree | −0.268*** | −0.290*** | −0.299*** | −0.332*** | |

| (0.076) | (0.076) | (0.072) | (0.071) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.129 | 0.165 | 0.210 | 0.214 | |

| Panel C: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Gender earnings gap (district) | −0.473*** | −0.481*** | −0.494*** | −0.525*** | −0.647** |

| (0.158) | (0.159) | (0.152) | (0.152) | (0.273) | |

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 |

| R2 | 0.128 | 0.164 | 0.209 | 0.212 | 0.344 |

Notes: This table presents estimates from regressions of candidates’ gender on the fraction of respondents in each département in the 2006 GGS who agree with the statement “Men are better political leaders than women” (panel A) and those who agree with the statement “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” (panel B) and on (residualized) gender earnings gaps (panel C). Regressions include election × party fixed effects. Columns (2)–(5) include dummies for candidates’ age, elite university education, and high-skill occupations. Columns (3)–(5) include dummies for incumbents, first-time candidates, and former government members, as additional controls. Columns (4) and (5) also control for the vote share obtained by the candidate’s party in the previous Presidential election. Column (5) includes district fixed effects (panel C only). The sample is restricted to candidates from the main Left and Right party coalitions. Regressions are at the candidate–district level over the Parliamentary elections between 1988 and 2017. Standard errors presented in parentheses are clustered at both the candidate and département levels in panels A and B and at both the candidate and district × election levels in panel C. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | −0.228* | −0.269** | −0.267** | −0.301*** | |

| (0.120) | (0.119) | (0.115) | (0.115) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.127 | 0.163 | 0.208 | 0.211 | |

| Panel B: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men more right to a job: % agree | −0.268*** | −0.290*** | −0.299*** | −0.332*** | |

| (0.076) | (0.076) | (0.072) | (0.071) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.129 | 0.165 | 0.210 | 0.214 | |

| Panel C: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Gender earnings gap (district) | −0.473*** | −0.481*** | −0.494*** | −0.525*** | −0.647** |

| (0.158) | (0.159) | (0.152) | (0.152) | (0.273) | |

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 |

| R2 | 0.128 | 0.164 | 0.209 | 0.212 | 0.344 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men better political leaders: % agree | −0.228* | −0.269** | −0.267** | −0.301*** | |

| (0.120) | (0.119) | (0.115) | (0.115) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.127 | 0.163 | 0.208 | 0.211 | |

| Panel B: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Men more right to a job: % agree | −0.268*** | −0.290*** | −0.299*** | −0.332*** | |

| (0.076) | (0.076) | (0.072) | (0.071) | ||

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | |

| Observations | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | 6,989 | |

| R2 | 0.129 | 0.165 | 0.210 | 0.214 | |

| Panel C: | Female candidate? | ||||

| Gender earnings gap (district) | −0.473*** | −0.481*** | −0.494*** | −0.525*** | −0.647** |

| (0.158) | (0.159) | (0.152) | (0.152) | (0.273) | |

| Election × party fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp. | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Presidential party vote share | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| District fixed effects | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Observations | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 | 7,038 |

| R2 | 0.128 | 0.164 | 0.209 | 0.212 | 0.344 |

Notes: This table presents estimates from regressions of candidates’ gender on the fraction of respondents in each département in the 2006 GGS who agree with the statement “Men are better political leaders than women” (panel A) and those who agree with the statement “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” (panel B) and on (residualized) gender earnings gaps (panel C). Regressions include election × party fixed effects. Columns (2)–(5) include dummies for candidates’ age, elite university education, and high-skill occupations. Columns (3)–(5) include dummies for incumbents, first-time candidates, and former government members, as additional controls. Columns (4) and (5) also control for the vote share obtained by the candidate’s party in the previous Presidential election. Column (5) includes district fixed effects (panel C only). The sample is restricted to candidates from the main Left and Right party coalitions. Regressions are at the candidate–district level over the Parliamentary elections between 1988 and 2017. Standard errors presented in parentheses are clustered at both the candidate and département levels in panels A and B and at both the candidate and district × election levels in panel C. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

In panel B, we use the statement “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women”, and find very similar results. If anything, the economic and statistical significances of the estimates are stronger.

Panel C reports the estimates of β when using gender earnings gaps as a proxy for voters’ attitudes, which varies both across electoral districts and over time.26 As for panels A and B, the coefficients are negative, statistically significant at conventional levels, and stable across specifications. The estimates are also economically large: a one standard deviation increase in the gender earnings gaps is associated with at least a 2 percentage point decrease in the probability that the candidate in that district is a woman. Note that we introduce district fixed effects in column (5), so that the coefficient is now identified through within-district variations in the gender earnings gap over time. We still obtain a large and negative coefficient.

Overall, we find converging evidence that female candidates are less likely to run for elections in areas with (relatively) unfavorable attitudes toward women. One explanation for this pattern—formalized in the model presented in Section 4—is that parties anticipate a lower probability of winning elections when female candidates run in districts with unfavorable attitudes toward women. However, one might think of alternative explanations, such as, for instance, the possibility that the local supply of female versus male candidates vary across districts with more or less favorable attitudes toward women.27 We thus directly test below whether female candidates indeed obtain lower votes in areas with less favorable attitudes toward women.

3.2. Voters’ Attitudes and Gender Gaps in Vote Shares

We will interpret a negative sign for the main parameter of interest β in equation (2) as supportive evidence that female candidates obtain lower votes in municipalities with higher gender earnings gaps. While reverse causality should not be a threat to our interpretation since the evidence comes from within-constituency comparison, which shuts down differential response by women candidates, one may still worry about omitted variable bias: (i) the possibility that what drives the correlation between earning gaps and female candidates’ vote shares is not really candidates’ gender but correlated candidate-level factors; and (ii) the possibility that what drives the correlation is not really the earnings gap but correlated municipality-level factors such as the sex ratio. We address below the first set of concerns with the inclusion of a series of candidates’ characteristics other than gender in interaction with earnings gaps in equation (2), the vector |${\textit{GenderEarningsGap}}_{m,t} \times X_{i,t}$|. We address the second set of concerns by introducing in augmented specifications the gender dummy interacted with a list of municipality-level confounders.

Table 3 reports estimates for our main parameter of interest β. The coefficient β on the interaction between gender earnings gaps and the dummy for female candidates is negative and statistically significant (at 1% confidence level) in all specifications: female candidates obtain on average lower vote shares compared to male candidates in municipalities in which the male–female earnings gap is larger. We gradually introduce candidate × election fixed effects and controls for candidates’ characteristics (dummies for elite education and for high-skill occupations, and previous political experience) in interaction with earnings gaps. Importantly, we introduce the party affiliation of the candidate interacted with earnings gaps in column (5). This controls for the concern that high gender earnings gap municipalities are more likely to vote for the Right party, of which women are less likely to be a member.29 Reassuringly, the β coefficient is still negative and statistically significant at the 1% confidence level. In column (6), we find that the coefficient β is similar for female candidates from the Left and the Right parties. This suggests that gender attitudes translate into the same gender electoral gaps whatever the ideology of voters.30

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote share—round 1 | ||||||

| Female × gender earnings gap | −0.421*** | −0.364*** | −0.275*** | −0.197*** | −0.078** | |

| (0.055) | (0.039) | (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.033) | ||

| Female × Right party × gender earnings gap | −0.058 | |||||

| (0.046) | ||||||

| Female × Left party × gender earnings gap | −0.090** | |||||

| (0.041) | ||||||

| Female | −0.029*** | |||||

| (0.004) | ||||||

| Municipalities × election fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Candidate × election fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation × earnings gap | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp., × earnings gap | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Right party × earnings gap | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 |

| R2 | 0.680 | 0.891 | 0.892 | 0.893 | 0.895 | 0.895 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote share—round 1 | ||||||

| Female × gender earnings gap | −0.421*** | −0.364*** | −0.275*** | −0.197*** | −0.078** | |

| (0.055) | (0.039) | (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.033) | ||

| Female × Right party × gender earnings gap | −0.058 | |||||

| (0.046) | ||||||

| Female × Left party × gender earnings gap | −0.090** | |||||

| (0.041) | ||||||

| Female | −0.029*** | |||||

| (0.004) | ||||||

| Municipalities × election fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Candidate × election fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation × earnings gap | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp., × earnings gap | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Right party × earnings gap | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 |

| R2 | 0.680 | 0.891 | 0.892 | 0.893 | 0.895 | 0.895 |

Notes: This table presents estimates from regressions of candidates’ vote shares in the first round of the Parliamentary elections on a female candidate dummy interacted with residualized gender earnings gap at the municipality level, and control variables. Earnings gaps are computed at the inter-municipality level for small municipalities (defined as those below 2,000 inhabitants). All regressions include municipality × election fixed effects. Columns (2)–(5) include candidate × election fixed effects. Some specifications include controls for the interaction between residualized gender earnings gap and other characteristics of candidates (age, elite university education, high-skill occupation, political experience, and party affiliation). The sample is restricted to candidates from the two main party coalitions. Regressions are at the candidate–municipality level over the Parliamentary elections from 1993 to 2017. Standard errors presented in parentheses are clustered at both the candidate and municipality–election levels, and regressions are weighted by total population in each municipality. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote share—round 1 | ||||||

| Female × gender earnings gap | −0.421*** | −0.364*** | −0.275*** | −0.197*** | −0.078** | |

| (0.055) | (0.039) | (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.033) | ||

| Female × Right party × gender earnings gap | −0.058 | |||||

| (0.046) | ||||||

| Female × Left party × gender earnings gap | −0.090** | |||||

| (0.041) | ||||||

| Female | −0.029*** | |||||

| (0.004) | ||||||

| Municipalities × election fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Candidate × election fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation × earnings gap | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp., × earnings gap | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Right party × earnings gap | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 |

| R2 | 0.680 | 0.891 | 0.892 | 0.893 | 0.895 | 0.895 |

| . | (1) . | (2) . | (3) . | (4) . | (5) . | (6) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote share—round 1 | ||||||

| Female × gender earnings gap | −0.421*** | −0.364*** | −0.275*** | −0.197*** | −0.078** | |

| (0.055) | (0.039) | (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.033) | ||

| Female × Right party × gender earnings gap | −0.058 | |||||

| (0.046) | ||||||

| Female × Left party × gender earnings gap | −0.090** | |||||

| (0.041) | ||||||

| Female | −0.029*** | |||||

| (0.004) | ||||||

| Municipalities × election fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Candidate × election fixed effects | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age, education, occupation × earnings gap | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Incumbent, first run, government exp., × earnings gap | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Right party × earnings gap | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 | 286,121 |

| R2 | 0.680 | 0.891 | 0.892 | 0.893 | 0.895 | 0.895 |

Notes: This table presents estimates from regressions of candidates’ vote shares in the first round of the Parliamentary elections on a female candidate dummy interacted with residualized gender earnings gap at the municipality level, and control variables. Earnings gaps are computed at the inter-municipality level for small municipalities (defined as those below 2,000 inhabitants). All regressions include municipality × election fixed effects. Columns (2)–(5) include candidate × election fixed effects. Some specifications include controls for the interaction between residualized gender earnings gap and other characteristics of candidates (age, elite university education, high-skill occupation, political experience, and party affiliation). The sample is restricted to candidates from the two main party coalitions. Regressions are at the candidate–municipality level over the Parliamentary elections from 1993 to 2017. Standard errors presented in parentheses are clustered at both the candidate and municipality–election levels, and regressions are weighted by total population in each municipality. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Taking column (5) as our preferred specification, we obtain that a one standard deviation in gender earnings gap (7.2 percentage points at the municipality level) is associated with a decrease by 0.6 percentage points (0.072 * 0.078) in the vote share of female candidates (relative to male candidates).31 For means of comparison, note that in our sample, there are around 12% of tight outcomes in the second round of the Parliamentary elections with vote margins between the two candidates within ±1% (in which case a difference of 1 percentage points would change the outcome of the election). This confirms that voters’ attitudes matter quantitatively for electoral outcomes between male and female candidates.32

Robustness

In Robustness checks presented in Online Appendix Table A.3, we take our specification in column (5) of Table 3 and add the gender dummy interacted with other municipality characteristics (that could arguably confound the effect of voters’ attitudes on gender electoral gaps documented in Table 3). For example, one potential concern is that male voters could tend to prefer male candidates, while female voters tend to prefer female candidates. If gender earnings gaps are correlated with sex ratios across municipalities, this could confound the interpretation of our coefficient of interest. Instead, we find in column (1) of Online Appendix Table A.3 that the estimate on the interaction term between earnings gap and the female candidate dummy is unchanged when we control for the interaction of the sex ratio and the female candidate dummy. More generally, Online Appendix Table A.3 shows that our coefficient of interest is unaffected when we further interact the female candidate dummy with total population in the municipality, the overall employment rate, or the share of men among employed workers.

One remaining concern that is not fully addressed by our within-candidate framework is that women running for elections would be more likely to live or come from municipalities with more favorable gender attitudes, and could obtain more votes in these municipalities because of their local roots. To tackle this concern, we run the same regression as above in which we add a dummy for whether candidate i has been either council member or the mayor in municipality j. If the larger fraction of votes obtained by female candidates in municipalities with low gender earnings gap simply reflects a “home bias”, including this control would arguably absorb part of the main coefficient of interest Female × Gender Earnings Gaps. We present the results in Online Appendix Table A.4. First, we do find strong evidence that candidates with a local mandate in a given municipality obtain larger vote shares when running for Parliamentary election. However, including the control for local mandate has virtually no effect on the coefficient of interest Female × Gender Earnings Gaps. This largely mitigates the residual concern that selection into politics within districts could explain our findings.

One econometric concern is that gender earnings gaps are not precisely estimated in small municipalities. While Table 3 includes all municipalities, we show in Online Appendix Table A.5 that the results are robust in unweighted regressions restricted to municipalities with more than 2,000 inhabitants.33 Finally, we show in Online Appendix Table A.6 that the results are robust to using gender gaps in raw earnings or in earnings residualized with fewer controls.

Overall, we interpret the results presented in Tables 2–3 as evidence that voters’ attitudes toward women matter quantitatively for understanding gender differences in both selection into politics and electoral outcomes. We use these stylized facts as a motivation for building a model of electoral competition in which parties select candidates taking into account that voters might have a systematic preference for either male or female candidates, referred to as “gender voter bias” in what follows.

4. Model of Electoral Competition

We aim at modeling electoral competition in single-member district majoritarian elections with two main parties.34 We build on Galasso and Nannicini (2011) and propose a model of political selection in which parties choose between candidates that differ in terms of valence and gender in order to win elections. Our theoretical innovation is to add gender as an additional source of heterogeneity across candidates along with a potential voter gender bias (which then makes gender an important attribute of candidates in the model).

The model provides new insights into how voter gender bias and gender quotas affect political selection, and ultimately the gender composition of elected politicians. Specifically, the main contribution of the model is to provide a theory in which the political under-representation of women is partly explained by parties’ strategic response to voters’ bias. We show that the presence of voter gender bias endogenously generates a strategic party bias in the presence of gender quotas, that is, parties refrain from selecting female (respectively, male) candidates in the most contestable districts when voters have a preference for male (respectively, female) candidates. This insight serves as a model-based test for the presence (and sign) of voter bias that we bring to the data in Section 5. We present an extension of the model with intrinsic party bias in Online Appendix C that highlights the robustness of our model-based test for the presence of voter gender bias. The second contribution of the model, which we develop in Section 6, is to show how parties’ strategic decisions alter the effectiveness of gender quotas in the presence of electoral competition.

4.1. Setup

We consider two main parties: Left and Right (denoted L and R below), and k = 1, …, N electoral districts. The two parties occupy fixed positions in the ideology profile: IL = −1 and IR = 1. They compete under a single-member district majority rule. The elected candidate provides support for her/his ideology and constituency services for her/his district. Each potential candidate has a personal valence that can be understood as a combination of her/his education, oral ability, political experience, and effort at work. Districts vary by their local ideology, so that some are contestable, while in others the candidate of one party (either L or R) is ex-ante likely to win the seat.

Parties and Districts

Candidates

In each district, party R (respectively, L) chooses between two local candidates—a female candidate and a male candidate—with valence |$\theta ^F_{R,k}$| and |$\theta ^M_{R,k}$| (respectively, |$\theta ^F_{L,k}$| and |$\theta ^M_{L,k}$|).36 The assumption that parties select candidates among a pool of local candidates, as opposed to allocating a national pool of candidates across electoral districts, is consistent with the data. We find that 80% of candidates either hold (or used to hold) a local mandate in the council of one municipality of the same district and/or run in the same district for parliamentary election in one of the previous elections.37 We assume that female and male candidates’ valences are drawn from the same uniform distribution |$\mathcal {U}[-\bar{\theta }, \bar{\theta }]$|.38 The valence of each candidate is common knowledge.

Voters and Electoral Competition

|Ik − IL| − |Ik − IR| + θR,k − θL,k − bFR,k + bFL,k can be interpreted as an ex-ante score of party R in district k (i.e., before the realization of the campaign electoral shock δk). Φ( · ) maps ex-ante score into expected probability of winning the election in a given district.

Timing

We adopt the following timing for the electoral game that the two parties play in each district k: (stage 1) nature draws the local ideology Ik, the potential candidates’ valences |$\lbrace \theta _{R,k}^F,\theta _{R,k}^M,\theta _{L,k}^F,\theta _{L,k}^M\rbrace$|, and which party chooses its local candidate first (say L in what follows); (stage 2) party L chooses its candidate in {FL,k,ML,k}; (stage 3) party R chooses its candidate in {FR,k,MR,k}; and (stage 4) nature draws the campaign popularity shock δk, voters vote, and one candidate is elected.

We assume that the probability of moving first is the same for both parties.43 All nature draws are common knowledge.

Equilibrium

We solve for a subgame perfect equilibrium. The equilibrium in each district k is the gender pair of the Left and Right candidates (FL,k,FR,k) [either (0,0), (1,1), (0,1), or (1,0)] and it depends on the parameters |$\lbrace c,b,I_k,\theta ^F_{R,k},\theta ^M_{R,k},\theta ^F_{L,k},\theta ^M_{R,k}\rbrace$|. We formally solve for the equilibrium of the game for all parameter values in Online Appendix B. In the next section, we give the main intuition for political parties’ best responses in the selection of female or male candidates in each district.

4.2. Parties’ Selection of Candidates

The main intuition, described in this section, is that the decision of selecting a female versus a male candidate depends in particular on the difference in valence between the two candidates, the degree of voter bias, and the degree of political competition in the district when there is a cost (c > 0) of deviating from the gender parity rule on candidates. To begin with, we describe parties’ selection of male or female candidates across electoral districts for the case c = 0 (without costs for deviating from the parity rule on candidates).

Pre-Quota Environment Benchmark (c = 0)

In the absence of gender quotas (c = 0), parties’ objective (see equation (3)) boils down to maximizing VR,k, the probability of winning the election in each district. It follows that in each district, each party selects from between the male and female candidates the one with the best chance of winning. That is, party R (the same applies to L) chooses the female candidate if and only if |$\theta _{R,k}^F-b>\theta _{R,k}^M$|, and the male candidate otherwise. The following lemma summarizes the selection of candidates and characterizes the aggregate gender composition of candidates when c = 0. The proof is in Online Appendix B.

In the absence of gender quotas (c = 0), in each district k, party R (the same applies to L) selects the female candidate if |$\theta _{R,k}^{F}-\theta _{R,k}^{M} \ge b$|, and the male candidate otherwise.

The voter gender bias, b, affects the aggregate fraction of male versus female candidates. When voters have a preference for male politicians (b > 0), parties select female candidates only when their valence is large enough to compensate for the degree of voter bias. Aggregating over the (uniform) distribution of valence, the share of female candidates is |$1/2-b/(2\bar{\theta })$|. That is, the share of female candidates running for election is exactly 50% in the absence of voter bias, and below 50% (respectively, above 50%) when voters have a preference for male politicians b > 0 (respectively, for female politicians b < 0).

Post-Quota Environment (c > 0)

We now discuss the case when there is a cost for deviating from the parity rule on candidates (c > 0). We give the intuition of the model solution in an environment with voter bias in favor of male candidates—that is, b > 0. This is without loss of generality: as the model is symmetric, the case with b < 0 can be described as below after switching notations for male and female candidates.44

Suppose that |$\theta _{R,k}^{F}<\theta _{R,k}^M+b$|, in which case party R would choose a male candidate in the absence of quota (see Lemma 1). When c > 0, party R might instead consider choosing a female candidate even if the probability of winning would be strictly greater when choosing the male candidate: the presence of the quota introduces a trade-off between the cost of the parity rule and the electoral cost of choosing a female candidate over a male candidate.

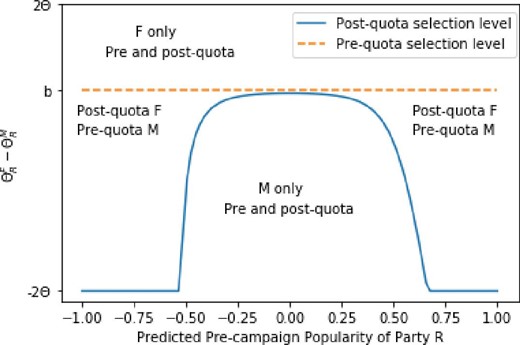

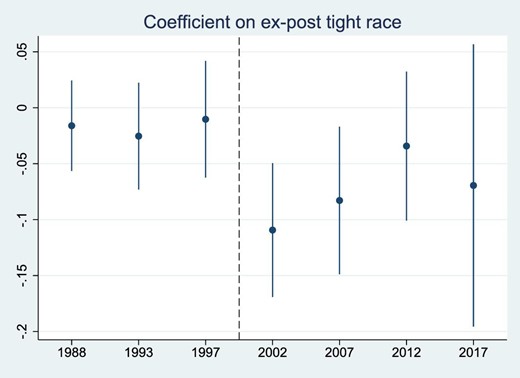

Party R finds it optimal to select a female candidate in district k if and only if c > Φ(SR,k) − Φ(SR,k − bR,k). Figure 2 shows the “electoral cost” of choosing a female candidate over a male candidate with equal valence, for different levels of pre-campaign popularity (or ex-ante score SR,k). The vertical arrows represent the electoral cost—formally equal to Φ(SR,k) − Φ(SR,k − b). The electoral cost is large in districts in which electoral contestability is high: SR,k close to 0 [Φ(SR,k) close to 1/2]. As a result, everything else equal, gender quotas push parties to choose female candidates over male candidates in districts in which electoral competition is low—that is, in districts where party R is either very likely to win (SR,k gets closer to 1) or very likely to lose (SR,k gets closer to −1). By contrast, when electoral competition is high, parties would tend to stick to the candidate that maximizes the probability of winning the election: choosing instead a female candidate when |$\theta ^F_{R,k}<\theta ^M_{R,k}+b$| would often generate an electoral cost that outweighs the reduction in the cost c from gender quotas.

Voter bias and electoral cost when selecting female versus male candidates. This figure illustrates the change in the probability of winning the election when selecting a female instead of a male candidate of the same valence: θF = θM for different expected scores (pre-campaign popularity). The (blue) curve is the cumulative distribution function of the campaign shock.

To further describe the optimal selection rule of party R in stage 3 of the game, we define the change in score from the initial score SR,k (“the score gap”, denoted SG below) such that the probability of winning the election in a given district decreases by c. Lemma 2 then characterizes the selection rule. The proof is in Online Appendix B.

Define SGR,k such that Φ(SR,k) − Φ(SR,k − SGR,k) = c. In each district k, party R selects the female candidate if |$\theta _{R,k}^{F}-\theta _{R,k}^{M} \ge b-SG_{R,k}$|, and the male candidate otherwise. The score gap SGR,k —and therefore the probability of selecting a female candidate—decreases with electoral competition, and is minimized at |$S_R^* =c \sigma \sqrt{\pi /2}$| for c arbitrarily small, where σ is the standard deviation of the campaign electoral shock.

The score gap SGR,k represents a threshold in the selection rule of party R. Party R will select a female candidate in a given district if |$\theta ^F_{R,k}-b>\theta ^M_{R,k}-SG_{R,k}$|, and the male candidate otherwise. We can then interpret SGR,k as the distortion in the selection rule due to the costs of gender quotas. That is, for |$\theta ^M_{R,k}+b-SG_{R,k}<\theta ^F_{R,k}<\theta ^M_{R,k}+b$|, the party internalizes gender quotas and selects a female candidate, even though the probability of winning the local election would have been larger with the male candidate.

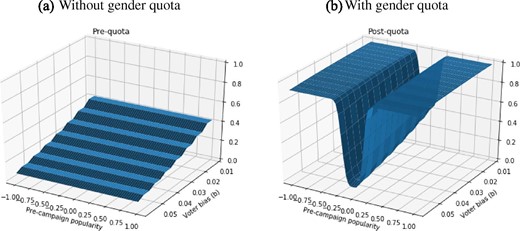

Figure 3 illustrates the distortion induced by the gender quota and how it varies with electoral competition (ex-ante score in the X-axis). The Y-axis represents the difference in valence between the female and male candidates (|$\theta _{R,k}^{F}-\theta _{R,k}^{M}$|). The solid curve plots b − SGR,k. When the valence draws are above the solid curve, party R selects the female candidate. In the absence of quota, party R selects female candidates above the dashed line. The area between the dashed line and the solid curve represents the increase in female candidates due to the gender quota. It is thinner in contestable districts, when the score gap is minimal. The second part of Lemma 2 shows formally that the minimum is obtained when SR,k → 0 (for low values of c), that is, when the ex-ante probability of winning the election Φ(SR,k) is close to 1/2.

Candidates’ valence and party selection rule. X-axis: pre-campaign popularity of party R (SR varies from −1 to 1). Y-axis: difference between the valence of the female and male candidates, θF − θM (varies from |$-2\bar{\theta }$| to |$2\bar{\theta }$|). The dashed line presents the selection rule for c = 0, that is, party R selects the female candidate if |$\theta _{R,k}^{F}-\theta _{R,k}^{M} \ge b$|, and the male candidate otherwise. The solid line presents the selection rule for c > 0, that is, party R selects the female candidate if |$\theta _{R,k}^{F}-\theta _{R,k}^{M} \ge b-SG_{R,k}$|, and the male candidate otherwise.

Up to now, we gave the intuition considering the party that plays second (in stage 3). We now show that this result extends for the average share of female candidates in equilibrium across both parties. For this, we simulate the equilibrium gender pairs characterized in the Online Appendix drawing in each district the valence of candidates. We compute from these simulations the aggregate fraction of female candidates running for election, for different levels of pre-campaign popularity and initial voter gender bias b > 0. Figure 4 plots the aggregate fraction of female candidates for both the cases of without (panel A) and with (panel B) a cost for deviating from the parity rule. As shown in panel A, the aggregate fraction of female candidates selected by each party is decreasing in voter gender bias b, but independent of the degree of contestability in the absence of gender quotas [equal to |$P(\theta _{R,k}^{F}-\theta _{R,k}^{M} \ge b)=1/2-b/(2\bar{\theta })$|]. As shown in panel B, political parties react strategically to the introduction of the parity rule by selecting disproportionately more female candidates in non-contestable districts.

Share of women candidates, competition, and voter gender bias. X-axis: pre-campaign popularity of party R (SR varies from −1 to 1). Y-axis: voter gender bias (b varies from 0.02 to 0.08). Z-axis: share of female candidates.

Identifying the Sign of Voter Bias

Intuitively, observing the allocation of male and female candidates across contestable and non-contestable districts is informative on the sign of the voter bias. We formalize this intuition in the following proposition (see proof in Online Appendix B):

When there are gender quotas on candidates (c > 0):

the share of female candidates is lower in contestable than in non-contestable districts when b > 0 (voter bias in favor of male politicians);

the share of female candidates is higher in contestable than in non-contestable districts when b < 0 (voter bias in favor of female politicians);

the share of female candidates is the same in contestable and non-contestable districts when b = 0 (no voter gender bias).