-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kira Oleinikov, Alain Dancour, Julia Epshtein, Ariel Benson, Haggi Mazeh, Ilanit Tal, Shay Matalon, Carlos A Benbassat, Dan M Livovsky, Eran Goldin, David J Gross, Harold Jacob, Simona Grozinsky-Glasberg, Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Radiofrequency Ablation: A New Therapeutic Approach for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 104, Issue 7, July 2019, Pages 2637–2647, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2019-00282

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation (EUS-RFA) is rapidly emerging as feasible therapy for patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) in selected cases, as a result of its favorable safety profile.

To assess the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of EUS-RFA in a cohort of patients with functional and nonfunctional pNETs (NF-pNETs).

Data on pNET patients treated with EUS-RFA between March 2017 and October 2018 at two tertiary centers was retrospectively analyzed.

The cohort included 18 adults (eight women, 10 men), aged 60.4 ± 14.4 years (mean ± SD), seven insulinoma patients, and 11 patients with NF-pNETs. Twenty-seven lesions with a mean diameter of 14.3 ± 7.3 mm (range 4.5 to 30) were treated. Technical success defined as typical postablative changes on a surveillance imaging was achieved in 26 out of 27 lesions. Clinical response with normalization of glucose levels was observed in all (seven of seven) insulinoma cases within 24 hours of treatment. Overall, there were no major complications 48 hours postprocedure. No clinically significant recurrences were observed during mean follow-up of 8.7 ± 4.6 months (range 2 to 21 months).

EUS-guided RFA of pNETs is a minimally invasive, safe, and technically feasible procedure for selected patients.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (pNENs) represent a group of wide-ranging biological variability tumors that comprise <3% of all primary pancreatic malignancies (1, 2). With the application of the World Health Organization 2017 classification, two groups of pNENs are morphologically distinguished: well-differentiated tumors, so-called pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs), and poorly differentiated neoplasms, so-called small or large cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas. The importance of the distinction of pNETs from pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas was further emphasized by the introduction of a new tier of Grade 3 (G3) pNETs, based on the new insights of pNEN genetics and clinical observation of different responses to therapy (3).

Although pNETs represent a relatively rare entity, their diagnosis has increased four- to sixfold over the last decades as a result of the availability of cross-sectional imaging (4, 5). Two trends became apparent in the course of the pNET growing incidence: a higher frequency of incidental findings and a smaller size of the detected lesion at diagnosis (6–11). This tendency narrows the gap between annual clinical detection rate (0.8:100,000) and autopsy series prevalence (0.5% to 1.5%), thereby altering a standpoint regarding mortality rates in patients with asymptomatic neoplasms and consequently, an adequate treatment approach (5, 12–15).

The optimal management of pNETs involves a multimodal approach, reflective of their heterogeneity, namely, tumor size, grade, stage, functional status, rate of progression, association with genetic syndromes, etc. (16, 17). In addition, patients’ performance status and comorbidities have a profound impact on the therapeutic choice. These approaches are still evolving in pursuit of maximization of disease control and patient survival with the maintenance of quality of life.

With the assumption that all pNETs may be potentially malignant, surgical excision of localized disease appears, in principle, to be the only curative option (17). In practice, as >70% of the tumors are nonfunctioning and up to 50% are incidentally discovered as asymptomatic lesions, the question may be raised whether morbidity and mortality rates of the surgical approach are justifiable in all cases. Therefore, for small (<1.5 to 2 cm), well-differentiated, asymptomatic, and nonfunctioning pNETs (NF-pNETs), the option of active surveillance was proposed, although it still entails the possibility of metastatic disease development (17–22). For a sizable group of patients in whom the cytoreductive approach is indicated, as a result of either worrisome tumor features or functional status, but who are not considered as candidates for surgery, as a result of high perioperative risk or personal preferences, an alternative therapeutic approach is essential.

Thus, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in endoscopic ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation (EUS-RFA), a technique that induces tumor mass thermal necrosis as a potentially curative technique that seems to carry a low periprocedural complications risk. However, data regarding the effectiveness and safety of EUS-RFA in patients with pNETs are scarce. In the current study, we retrospectively analyzed the initial experience in regard to procedural feasibility, safety, as well as clinical outcome of EUS-RFA treatment in a group of both functional (insulinomas) and NF-pNET patients. We have also reviewed the literature to compare our experience with the limited series previously reported.

Subjects and Methods

From March 2017 to October 2018, 18 consecutive patients diagnosed with pNENs were selected for EUS-RFA treatment at two tertiary referral centers in Israel. The patients’ data were retrospectively analyzed.

Inclusion criteria for EUS-RFA were as follows: (i) histopathologic diagnosis of well-differentiated pNEN; (ii) insulinoma; (iii) NF-pNET; (iv) localized; (v) minimally advanced pNET (including multiple pNETs and/or simultaneous liver or regional lymph node metastases, where an EUS-RFA strategy for all detectable lesions was feasible); (vi) ineligibility for or refusal of surgery; (vii) informed nonconsent for initially recommended, active surveillance (for low-grade, smaller than 2 cm, NF-pNET); and (viii) a life expectancy of >24 months.

Exclusion criteria were the following: (i) lesion size > 3 cm; (ii) evidence of tumor proximity to vital adjacent organs and/or major arteries on imaging; and (iii) age younger than 18 years.

The decisions for treatment strategy were discussed by a multidisciplinary team. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, according to World Medical Association Helsinki guidelines for research in human subjects.

Periprocedure evaluation and management

The work-up included complete clinical histories and physical examinations, routine laboratory tests, as well as disease-related markers. In all patients with hypoglycemia-related symptoms, the diagnosis of insulinoma was confirmed by the presence of hypoglycemia and concomitant, inappropriately high-serum insulin and C-peptide levels.

Imaging studies [standard EUS and contrast enhanced spiral CT (CECT)] were performed in all cases; in addition, functional imaging [gallium 68-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid-octreotate (68Ga-DOTATATE) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT] was performed in 13 patients.

Tumor diagnosis was based on the histopathologic examination of EUS-guided biopsies. In patients with multiple lesions in the pancreas, at least one lesion (usually the largest) was biopsied.

All EUS-RFA procedures were performed on an inpatient basis under standard anesthesia care. Broad-spectrum prophylactic antibiotics were administered IV before the procedure. In all insulinoma cases, patients received a continuous 10% dextrose infusion before the procedure, in parallel with close glucose-level monitoring, during and at least 24 hours postprocedure.

EUS-RFA technique

Ultrasound-guided RFA was performed endoscopically using the EUS-RFA system (STARmed Co., Seoul, Korea), including a 19-gauge needle electrode, a radiofrequency generator, and an inner-cooling system that circulates chilled saline solution during the RFA procedure. RFA energy was applied in three to 10 cycles, each lasting 5 to 12 seconds at a power setting of 10 to 50 W. The energy was delivered only after EUS confirmed the location of the tip of the needle electrode to be within the margins of the lesion. The radiofrequency generator was then activated to deliver 50 W of ablation power. Upon activation, after a lag period, echogenic bubbles gradually started appearing around the needle, thereby indicating ablation at the site.

Evaluation of adverse events and response to EUS-RFA

Clinical and laboratory evaluation (including complete blood count, liver function tests, and serum amylase/lipase levels) was performed the next morning after the procedure. Complete radiological response was defined as the hyperechoic area at the tumor site on a contrast-enhanced EUS immediately after the procedure. In 12 of 18 cases, as part of the center procedure protocol, a CECT scan was performed 1 day after the procedure to exclude early adverse events. Radiological response at a 3 to 6 months follow-up was defined as the presence of a nonenhancing area (central necrosis) at the site of the ablated lesion on CECT; the formation of fibrotic tissue on the site of the ablated lesion on EUS; and loss of pathologic uptake on 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT. Incomplete radiological response was defined as persistence of remnant tissue at the tumor site on at least one of the imaging studies. Clinical response in patients with insulinoma was defined as resolution of hypoglycemia-related symptoms and normalization of glucose levels during follow-up.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the patients

The baseline characteristics of the patients with pNETs are shown in Table 1. The cohort included 18 adults [eight women (44%); mean age at diagnosis of 60.4 ± 14.4 years, range 28 to 82].

| Total patient number | 18 | |

| Female (%) | 8 (44) | |

| Mean age, y (range) | 60.4 (28–82) | |

| Tumor functionality (n) | Insulinoma (7) | Nonfunctional (11) |

| Sporadic | 6/7 | 9/11 |

| MEN1 associated | 1/7 | 2/11 |

| Presentation, n | ||

| Hypoglycemic episodes | 7/7 | — |

| Incidental finding | — | 8/11 |

| Follow-up in MEN1 patients | — | 2/11 |

| Obstructive jaundice | — | 1/11 |

| Biochemical evaluation, n | ||

| Positive fast test | 7/7 | — |

| Mean chromogranin A, ng/mL (range) | 39 (23–68) | 102 (51–164) |

| Tumor localization, n | ||

| CECT | 5/7 | 11/11 |

| 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT-positive uptake | 2/4 | 8/9 |

| EUS | 7/7 | 11/11 |

| Pancreatic lesion location, n | ||

| Head | 4 | 6 |

| Body | 2 | 6 |

| Uncinate | 3 | 2 |

| Tail | — | 2 |

| Lesion size, mm, mean (range) | 14.8 (12–19) | 14.2 (4.5–29) |

| Tumor focality, n | ||

| Unifocal | 5/7 | 7/11 |

| Multifocal | 2/7 | 4/11 |

| Metastases | — | 2 |

| WHO 2017 tumor grade, Ki67% (range) | ||

| G1 | 7/7 (1–2) | 8/11 (1–3) |

| G3 | — | 2/11 (34–40) |

| Indication for EUS-RFA referral, n | ||

| Ineligible for or refused surgery | 7/7 | 6/11 |

| Patient preference | — | 5/11 |

| Total patient number | 18 | |

| Female (%) | 8 (44) | |

| Mean age, y (range) | 60.4 (28–82) | |

| Tumor functionality (n) | Insulinoma (7) | Nonfunctional (11) |

| Sporadic | 6/7 | 9/11 |

| MEN1 associated | 1/7 | 2/11 |

| Presentation, n | ||

| Hypoglycemic episodes | 7/7 | — |

| Incidental finding | — | 8/11 |

| Follow-up in MEN1 patients | — | 2/11 |

| Obstructive jaundice | — | 1/11 |

| Biochemical evaluation, n | ||

| Positive fast test | 7/7 | — |

| Mean chromogranin A, ng/mL (range) | 39 (23–68) | 102 (51–164) |

| Tumor localization, n | ||

| CECT | 5/7 | 11/11 |

| 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT-positive uptake | 2/4 | 8/9 |

| EUS | 7/7 | 11/11 |

| Pancreatic lesion location, n | ||

| Head | 4 | 6 |

| Body | 2 | 6 |

| Uncinate | 3 | 2 |

| Tail | — | 2 |

| Lesion size, mm, mean (range) | 14.8 (12–19) | 14.2 (4.5–29) |

| Tumor focality, n | ||

| Unifocal | 5/7 | 7/11 |

| Multifocal | 2/7 | 4/11 |

| Metastases | — | 2 |

| WHO 2017 tumor grade, Ki67% (range) | ||

| G1 | 7/7 (1–2) | 8/11 (1–3) |

| G3 | — | 2/11 (34–40) |

| Indication for EUS-RFA referral, n | ||

| Ineligible for or refused surgery | 7/7 | 6/11 |

| Patient preference | — | 5/11 |

Values are in numbers (percentage) unless otherwise indicated. Normal values of chromogranin A, 25 to 115 ng/mL.

Abbreviations: Ki67, proliferation index of the tumor; MEN1, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome; WHO, World Health Organization.

| Total patient number | 18 | |

| Female (%) | 8 (44) | |

| Mean age, y (range) | 60.4 (28–82) | |

| Tumor functionality (n) | Insulinoma (7) | Nonfunctional (11) |

| Sporadic | 6/7 | 9/11 |

| MEN1 associated | 1/7 | 2/11 |

| Presentation, n | ||

| Hypoglycemic episodes | 7/7 | — |

| Incidental finding | — | 8/11 |

| Follow-up in MEN1 patients | — | 2/11 |

| Obstructive jaundice | — | 1/11 |

| Biochemical evaluation, n | ||

| Positive fast test | 7/7 | — |

| Mean chromogranin A, ng/mL (range) | 39 (23–68) | 102 (51–164) |

| Tumor localization, n | ||

| CECT | 5/7 | 11/11 |

| 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT-positive uptake | 2/4 | 8/9 |

| EUS | 7/7 | 11/11 |

| Pancreatic lesion location, n | ||

| Head | 4 | 6 |

| Body | 2 | 6 |

| Uncinate | 3 | 2 |

| Tail | — | 2 |

| Lesion size, mm, mean (range) | 14.8 (12–19) | 14.2 (4.5–29) |

| Tumor focality, n | ||

| Unifocal | 5/7 | 7/11 |

| Multifocal | 2/7 | 4/11 |

| Metastases | — | 2 |

| WHO 2017 tumor grade, Ki67% (range) | ||

| G1 | 7/7 (1–2) | 8/11 (1–3) |

| G3 | — | 2/11 (34–40) |

| Indication for EUS-RFA referral, n | ||

| Ineligible for or refused surgery | 7/7 | 6/11 |

| Patient preference | — | 5/11 |

| Total patient number | 18 | |

| Female (%) | 8 (44) | |

| Mean age, y (range) | 60.4 (28–82) | |

| Tumor functionality (n) | Insulinoma (7) | Nonfunctional (11) |

| Sporadic | 6/7 | 9/11 |

| MEN1 associated | 1/7 | 2/11 |

| Presentation, n | ||

| Hypoglycemic episodes | 7/7 | — |

| Incidental finding | — | 8/11 |

| Follow-up in MEN1 patients | — | 2/11 |

| Obstructive jaundice | — | 1/11 |

| Biochemical evaluation, n | ||

| Positive fast test | 7/7 | — |

| Mean chromogranin A, ng/mL (range) | 39 (23–68) | 102 (51–164) |

| Tumor localization, n | ||

| CECT | 5/7 | 11/11 |

| 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT-positive uptake | 2/4 | 8/9 |

| EUS | 7/7 | 11/11 |

| Pancreatic lesion location, n | ||

| Head | 4 | 6 |

| Body | 2 | 6 |

| Uncinate | 3 | 2 |

| Tail | — | 2 |

| Lesion size, mm, mean (range) | 14.8 (12–19) | 14.2 (4.5–29) |

| Tumor focality, n | ||

| Unifocal | 5/7 | 7/11 |

| Multifocal | 2/7 | 4/11 |

| Metastases | — | 2 |

| WHO 2017 tumor grade, Ki67% (range) | ||

| G1 | 7/7 (1–2) | 8/11 (1–3) |

| G3 | — | 2/11 (34–40) |

| Indication for EUS-RFA referral, n | ||

| Ineligible for or refused surgery | 7/7 | 6/11 |

| Patient preference | — | 5/11 |

Values are in numbers (percentage) unless otherwise indicated. Normal values of chromogranin A, 25 to 115 ng/mL.

Abbreviations: Ki67, proliferation index of the tumor; MEN1, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome; WHO, World Health Organization.

The study group was comprised of seven insulinoma patients and 11 NF-pNET patients with nine and 18 pNET lesions, respectively. In the insulinoma subgroup, six patients had sporadic disease, and one patient had a multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) syndrome association. All presented with symptoms of hypoglycemic episodes and were diagnosed with an insulin-producing tumor based on a positive, 72-hour fast test. The lesions were localized by CECT in five of seven cases; 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in two of four available studies; and EUS in seven of seven cases. Seven out of the nine lesions were localized in the pancreatic head or/and uncinate process. All lesions were well-differentiated G1 tumors with a mean size of 14.8 mm (range 12 to 19).

Following the diagnosis of insulinoma and the recommended treatment, six patients declined to undergo surgery. They were subsequently referred to and found eligible for EUS-RFA treatment. One patient had a prior unsuccessful attempt of laparoscopic enucleation of a tumor localized in the uncinate process, before the referral to tumor ablation treatment.

In the NF-pNET subgroup, nine patients had a sporadic tumor, and two patients had MEN1 syndrome association. Excluding one patient, all were asymptomatic at diagnosis, and lesions were discovered incidentally or on follow-up imaging in MEN1 syndrome patients. In a single case, the NF-pNET was discovered during the evaluation of a new-onset obstructive jaundice. The tumor was located in the pancreatic head and produced compression of the pancreatic duct that required a biliary stent placing.

Localizations of the lesions by CECT and EUS were successful in all cases. Somatostatin receptor imaging with 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT was positive in eight of nine patients when performed at diagnosis. Unifocal and multifocal lesions in the pancreas were found in seven and four patients, respectively. Two patients had synchronous single metastases: in one case, the patient had an incidentally discovered 25-mm pNET in the uncinate process with an adjacent 22-mm metastatic lymph node, whereas in the other case, the patient had MEN1 syndrome with a 4.5-mm lesion in the head of the pancreas in parallel with a synchronous single 8.5-mm liver metastasis.

On histopathologic evaluation of the tumors with adequate fine needle aspiration specimens, seven patients had G1 NF-pNETs (Ki67 proliferation index ≤ 3%), and two patients had well-differentiated G3 NF-pNETs (Ki67 range 34% to 40%). The remaining patient with a 7-mm lesion located in the pancreatic body had an inadequate fine needle aspiration specimen to grade the tumor.

Overall, within the NF-pNET subgroup, five patients were eligible for an active surveillance approach (G1-localized tumors sized <15 mm); however, they preferred cytoreductive treatment. In the remaining six patients in which surgery was initially indicated (based on tumor size, grade, and/or stage), three patients were not eligible for surgery as a result of high surgical risk, and three patients refused surgery.

EUS-RFA procedure

A total of 27 lesions with a mean size of 14.3 ± 7.3 mm (range from 4.5 to 30) were treated with EUS-RFA (Table 2). The location of the target lesions was the head of the pancreas (n = 10), body of the pancreas (n = 8), tail of the pancreas (n = 2), uncinate process (n = 5), single metastasis in the liver (n = 1), and single metastasis in a regional lymph node (n = 1).

| Case . | Age/Sex . | Diagnosis (Grade) . | Lesion: n, Location . | Lesion Size, mm . | Indication for EUS-RFA . | Adverse Events . | Follow-Up Imaging . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Head | 17 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 21 |

| 2 | 65/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 12 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 14 |

| 3 | 28/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, body | 13, 15 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 4 | 61/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, uncinate | 13, 13 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 5 | 56/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 19 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 6 | 73/M | Insulinoma (G1)a | 1, Head | 18 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 5 |

| 7 | 37/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Body | 13 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 3 |

| 8 | 64/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Body | 10 | Patient preference | Mild pancreatitis | N/A | N/A | 14 |

| 9 | 73/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Body | 10, 7 | Patient preference | None | EUS | CR | 14 |

| 10 | 58/F | NF-pNET (G3)a | 1, Head | 30 | Declined surgery | None | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| 11 | 64/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Head | 25 | Declined surgery | Mild pancreatitis | CECT + SRI | IR | 13 |

| 12 | 79/M | NF-pNET (N/A) | 1, Body | 7 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 10 |

| 13 | 57/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, tail | 14, 5 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 8 |

| 14 | 82/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Head | 29, 6 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 15 | 48/M | NF-pNET (G1)a | 2, Head, liver metastasis | 4.5, 8.5 | Declined surgery | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 16 | 52/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 3, Body, body, tail | 11, 10, 6 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 17 | 67/F | NF-pNET (G3) | 1, Head | 25 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 3 |

| 18 | 80/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, L.N. metastasis | 25, 22 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 2 |

| Case . | Age/Sex . | Diagnosis (Grade) . | Lesion: n, Location . | Lesion Size, mm . | Indication for EUS-RFA . | Adverse Events . | Follow-Up Imaging . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Head | 17 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 21 |

| 2 | 65/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 12 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 14 |

| 3 | 28/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, body | 13, 15 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 4 | 61/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, uncinate | 13, 13 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 5 | 56/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 19 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 6 | 73/M | Insulinoma (G1)a | 1, Head | 18 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 5 |

| 7 | 37/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Body | 13 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 3 |

| 8 | 64/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Body | 10 | Patient preference | Mild pancreatitis | N/A | N/A | 14 |

| 9 | 73/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Body | 10, 7 | Patient preference | None | EUS | CR | 14 |

| 10 | 58/F | NF-pNET (G3)a | 1, Head | 30 | Declined surgery | None | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| 11 | 64/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Head | 25 | Declined surgery | Mild pancreatitis | CECT + SRI | IR | 13 |

| 12 | 79/M | NF-pNET (N/A) | 1, Body | 7 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 10 |

| 13 | 57/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, tail | 14, 5 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 8 |

| 14 | 82/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Head | 29, 6 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 15 | 48/M | NF-pNET (G1)a | 2, Head, liver metastasis | 4.5, 8.5 | Declined surgery | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 16 | 52/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 3, Body, body, tail | 11, 10, 6 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 17 | 67/F | NF-pNET (G3) | 1, Head | 25 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 3 |

| 18 | 80/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, L.N. metastasis | 25, 22 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 2 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; F, female; IR, incomplete response (no change in size or decrease in diameter <50%.); L.N., lymph node; M, male; N/A, not available; SRI, somatostatin receptor imaging.

Patients with MEN1 syndrome; association with MEN1 syndrome.

| Case . | Age/Sex . | Diagnosis (Grade) . | Lesion: n, Location . | Lesion Size, mm . | Indication for EUS-RFA . | Adverse Events . | Follow-Up Imaging . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Head | 17 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 21 |

| 2 | 65/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 12 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 14 |

| 3 | 28/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, body | 13, 15 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 4 | 61/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, uncinate | 13, 13 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 5 | 56/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 19 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 6 | 73/M | Insulinoma (G1)a | 1, Head | 18 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 5 |

| 7 | 37/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Body | 13 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 3 |

| 8 | 64/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Body | 10 | Patient preference | Mild pancreatitis | N/A | N/A | 14 |

| 9 | 73/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Body | 10, 7 | Patient preference | None | EUS | CR | 14 |

| 10 | 58/F | NF-pNET (G3)a | 1, Head | 30 | Declined surgery | None | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| 11 | 64/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Head | 25 | Declined surgery | Mild pancreatitis | CECT + SRI | IR | 13 |

| 12 | 79/M | NF-pNET (N/A) | 1, Body | 7 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 10 |

| 13 | 57/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, tail | 14, 5 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 8 |

| 14 | 82/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Head | 29, 6 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 15 | 48/M | NF-pNET (G1)a | 2, Head, liver metastasis | 4.5, 8.5 | Declined surgery | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 16 | 52/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 3, Body, body, tail | 11, 10, 6 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 17 | 67/F | NF-pNET (G3) | 1, Head | 25 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 3 |

| 18 | 80/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, L.N. metastasis | 25, 22 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 2 |

| Case . | Age/Sex . | Diagnosis (Grade) . | Lesion: n, Location . | Lesion Size, mm . | Indication for EUS-RFA . | Adverse Events . | Follow-Up Imaging . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Head | 17 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 21 |

| 2 | 65/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 12 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 14 |

| 3 | 28/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, body | 13, 15 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 4 | 61/M | Insulinoma (G1) | 2, Head, uncinate | 13, 13 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 9 |

| 5 | 56/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Uncinate | 19 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 6 | 73/M | Insulinoma (G1)a | 1, Head | 18 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 5 |

| 7 | 37/F | Insulinoma (G1) | 1, Body | 13 | Patient preference | None | N/A | CR | 3 |

| 8 | 64/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Body | 10 | Patient preference | Mild pancreatitis | N/A | N/A | 14 |

| 9 | 73/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Body | 10, 7 | Patient preference | None | EUS | CR | 14 |

| 10 | 58/F | NF-pNET (G3)a | 1, Head | 30 | Declined surgery | None | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| 11 | 64/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 1, Head | 25 | Declined surgery | Mild pancreatitis | CECT + SRI | IR | 13 |

| 12 | 79/M | NF-pNET (N/A) | 1, Body | 7 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 10 |

| 13 | 57/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, tail | 14, 5 | Patient preference | None | CECT + SRI | CR | 8 |

| 14 | 82/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Head | 29, 6 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 7 |

| 15 | 48/M | NF-pNET (G1)a | 2, Head, liver metastasis | 4.5, 8.5 | Declined surgery | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 16 | 52/M | NF-pNET (G1) | 3, Body, body, tail | 11, 10, 6 | Patient preference | None | CECT | CR | 6 |

| 17 | 67/F | NF-pNET (G3) | 1, Head | 25 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 3 |

| 18 | 80/F | NF-pNET (G1) | 2, Uncinate, L.N. metastasis | 25, 22 | High surgical risk | None | CECT | CR | 2 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; F, female; IR, incomplete response (no change in size or decrease in diameter <50%.); L.N., lymph node; M, male; N/A, not available; SRI, somatostatin receptor imaging.

Patients with MEN1 syndrome; association with MEN1 syndrome.

Six patients who had multiple pancreatic lesions, including two patients who had synchronous pancreatic and metastatic lesions (liver and lymph node), were treated for their multiple lesions in a single procedure. Five patients collectively had six pNET lesions treated with EUS-RFA that were >2 cm. Two octogenarian patients with G1 pNET lesions had the following characteristics: one patient had two lesions, sized 29 mm and 6 mm in the pancreatic head (case 14), and the other patient had one lesion, sized 25 mm in the uncinate process together with a 25 mm in diameter lymph node metastasis. Two patients with G3 tumors (number 10 and 17), presented with, lesions sized 30 mm (Ki67 34%) and 25 mm (Ki67 40%), respectively; one additional patient (number 11) presented with a G1 lesion measured 25 mm in the pancreatic head.

Postablation clinical response

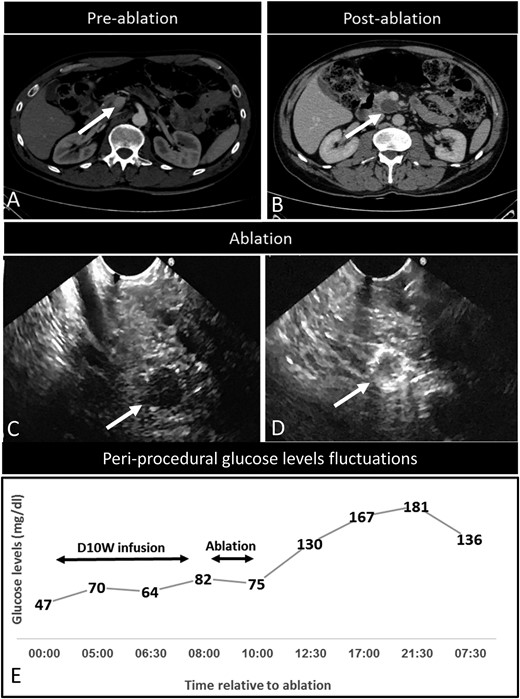

All seven patients with insulinomas exhibited complete relief of hypoglycemia-related symptoms. Normalization of glucose levels was observed within ∼1 hour after the procedure (Fig. 1E). The mean glucose levels of the seven insulinoma patients were 68 ± 6.1 mg/dL before the procedure and 119 ± 2.3 mg/dL after the procedure. No symptom recurrence was observed at a mean follow-up of 9.7 ± 5.6 months (range 3 to 21).

Disease characteristics in an insulinoma patient successfully treated with EUS-RFA (index patient number 2). (A) Three-phase CT examination (axial view), showing a contrast-enhanced lesion (12 mm in diameter) in the uncinate process of the pancreas (arrow), later diagnosed as an insulinoma. (B) Three-phase CT examination (axial view), 6 months after RFA. Complete ablation is reflected by the presence of a nonenhancing area at the ablation site (arrow). (C) EUS examination confirming the hypoechoic tumor lesion (arrow). (D) EUS image of the lesion obtained during the RFA. The peripheral hyperechoic area at the ablation site reproduced the shape of the treated tumor (arrow). (E) Time frame of glucose-level fluctuations in the patient before, during, and post-EUS-RFA procedure. Ablation, EUS-RFA procedure; D10W infusion, continuous 10% dextrose infusion.

Postablation imaging

Radiologic complete response (CR) was achieved in 17/18 patients. This was evident in 26 out of 27 treated lesions as a hyperechoic area seen on the tumor site on an EUS immediately after the procedure. Change in the vascularity of the treated lesions and central necrosis on a CECT were demonstrated the next day after the procedure in 12 patients. In addition, patient number 2 performed CECT at a 6-month follow-up, showing fibrotic tissue on the site of the ablated lesion (Fig. 1B). In one patient with a 25-mm lesion in the head of the pancreas (patient number 11), complete ablation was not achieved as a result of proximity to the main pancreatic duct (MPD). On postprocedure imaging, there was evidence of residual tissue on the tumor site adjacent to MPD.

Adverse events

Of the 18 ablation procedures, adverse events were recorded in two patients. One case (patient 11) developed mild pancreatitis following incomplete ablation of a 25-mm tumor in the pancreatic head. The symptoms of abdominal pain and pancreatic enzyme elevation appeared 10 days postprocedure and subsequently resolved after conservative treatment on the third day of hospitalization. The second case (patient 8) also developed mild pancreatitis, 1 week after ablation of a 10-mm lesion in the proximal pancreatic body, which also resolved with conservative treatment on the second day of hospitalization. Mean in-patient hospital stay for the cohort was 3 days (range 2 to 6).

Disease status during the follow-up period

During the mean follow-up period of 8.7 ± 4.6 months (range 2 to 21), no clinically significant recurrences were observed.

Discussion

In this study, we report our initial experience with EUS-RFA for treating selected cases of pNETs.

In terms of assessment of feasibility, the procedure was technically successful in 96% of ablated lesions, based on the response rate visualized by EUS immediately after the procedure. In a single case, where the tumor was in close proximity to the MPD, a complete ablation was not achieved. As previously reported, close proximity to MPD carries a risk of more severe complications and should represent a relative contraindication (23). Prophylactic stent insertion should be considered before the EUS-RFA procedure in high-risk cases, where the tumor is in close proximity to the MPD. All patients with symptomatic insulinomas achieved resolution of symptoms immediately after the procedure, with a lasting clinical response at the time of the final data analysis. No major complications were associated with the EUS-RFA procedure. Self-limiting and transient mild pancreatitis was observed in two patients (11%) and treated conservatively. Moreover, no signs of thermal injury of major vessels or of the MPD were visualized in patients with available follow-up studies.

Importantly, the expected efficacy of the procedure in relation to oncological outcomes should be discussed in the context of indications for different groups of patients in this heterogeneous cohort.

Our study group had a clear over-representation of patients with insulinomas. This selection bias reflects our multidisciplinary team opinion that these tumors may be the ideal candidates for ablation as a result of their indolent nature in most cases, younger age of patients, and possibility of earlier clinical detection in case of recurrence. It is noteworthy that the majority (six of seven) of insulinoma patients refused surgery, with preference to an initial ablative approach. Specifically in these tumors, ablation may be a valid, first alternative to surgery, considering that in the case of failure, surgical resection can still be performed.

Compared with insulinomas, NF-pNETs exhibit a greater variability of biological behavior, even within a specific grading category. Generally, surgery should be considered in the following scenarios: (i) symptomatic tumor; (ii) lesion size >2 cm; (iii) G2 and higher histological grade; (iv) involvement of MPD; (v) presence of resectable regional nodal metastases; (vi) presence of synchronous resectable distant metastases; and (vii) sporadic, localized, small NF-pNETs in young and healthy patients (as a result of unavailability of data on long-term follow-up) (16, 17). Within our cohort with NF-pNETs, six patients had an indication for surgery but were referred for ablation treatment as a result of the reasons stated before. This subgroup is particularly vulnerable to the current drawbacks of ablation therapy, as oncological safety of this procedure is not yet established. Moreover, tumor-free margins cannot be evaluated, and additional prognostic markers of tumor aggressiveness from histologic features (e.g., vascular/neural invasion) of the surgical tissue specimen are not available. Those patients are at a higher risk for recurrence and as a result, should be more closely monitored and in some cases, considered for systemic adjuvant therapy.

Another entity where EUS-RFA can be considered is incidentally diagnosed, small, asymptomatic NF-pNETs. Current European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society guidelines state that it is reasonable to follow these patients with serial imaging (16). This conservative approach is still regarded as controversial, and standardization of surveillance protocols is lacking (24). Furthermore, the patient’s emotional burden caused by the disease presence may be an important factor in the management. In some studies, with the comparison between surgery and a “wait and see” approach in small NF-pNETs, patients’ choice was a substantial reason to switch from observation to surgery (21, 25, 26). In our cohort, five patients with small NF-pNETs, who declined the initial active surveillance, were referred for ablation treatment. Given the quite fair life expectancy for patients with small pNETs and the relatively low complication rates of an EUS-RFA procedure, this appears to be an appropriate alternative to surgery.

A further challenge in the management of pNETs patients may occur in the setting of MEN1 syndrome, where typically the entire pancreas is involved. pNETs are the main cause of mortality in MEN1 patients, and total pancreatectomy is the only curative option in this circumstance. However, this is generally avoided as a result of a lifelong morbidity, including brittle diabetes and the negative sequelae of pancreatic insufficiency in young and otherwise healthy patients. Therefore, conservative treatment of small, nonfunctioning tumors is widely accepted, and tissue sparing surgery for functional or symptomatic pNETs is preferred (27, 28). Our cohort included three MEN1 patients with lesions that required a cytoreductive approach and were treated successfully with EUS-RFA.

Our entire cohort mean follow-up period was 8.7 months (range 2 to 21) with no clinically significant recurrences. The short duration of the follow-up represents a major limitation of this study, as most pNETs are slow-growing tumors, and observation may require 10 years or more to establish EUS-RFA efficacy. Until more data will be become available, each individual case should be carefully evaluated by a multidisciplinary team with regard to multifactorial features of the tumor and patient status.

On the whole, our findings confirm the previously published data on the feasibility of EUS-RFA in pNET patients, but the overall reported clinical experience is still limited (Table 3).

Summary of the Literature Regarding EUS-RFA Outcomes for pNETs Patients, Including Our Data

| Study . | Lesions, n . | Tumor Functionality . | Grade . | Lesion: n, Location . | Mean Size, mm (Range) . | Number of Ablation Sessions . | Complications . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo, Mean . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (23) | 1 | NF-pNET | N/A | Head | 9 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | N/A |

| (29) | 1 | NF-pNET | G2 | Tail | 20 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | 1 |

| (30) | 2 | NF-pNET | N/A | 2, Head | 27.5 (15–40) | 1–2 | None | Change in vascularity, central necrosis area 15 mm (2/2) | 1 |

| (31) | 3 | Insulinoma | N/A | 2, Head | 18 (14–22) | 1 | None | PR, symptom improved (3/3) | 12 |

| 1, Body | |||||||||

| (32) | 8 | NF-pNET (7) | G1 (1) | 3, Head | 19 (8–28) | 1–3 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (6/8) | 13 |

| Insulinoma (1) | G2 (1) | 5, Body | Abdominal pain (1) | IR (2/8) | |||||

| N/A (6) | |||||||||

| (33) | 14 | NF-pNET | G1 | 3, Head | 13.1 (10–20) | 1 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (12/14) | 12 |

| 6, Body | MPD stenosis (1) | IR (2/14) | |||||||

| 5, Tail | |||||||||

| (34) | 1 | Insulinoma | G1 | Body | 12 | N/A | Fever | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 2 |

| (35) | 3 | Insulinoma (2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | None | CR (N/A) | N/A |

| Vipoma (1) | Symptoms resolution (3/3) | ||||||||

| (36) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Uncinate | 18 | 3 | None | CR, symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| (37) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Body | 10 | 1 | None | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| Our study | 27 | Insulinoma (7) | G1 (15) | 10, Head | 14.3 (4.5–30) | 1 | Mild pancreatitis (2) | CR (26/27) | 8.7 |

| G3 (2) | 8, Body | IR (1/27) | |||||||

| 5, Uncinate | Symptoms resolution (7/7) | ||||||||

| 2, Tail | |||||||||

| 1, Liver metastasis | |||||||||

| 1, Lymph node metastasis |

| Study . | Lesions, n . | Tumor Functionality . | Grade . | Lesion: n, Location . | Mean Size, mm (Range) . | Number of Ablation Sessions . | Complications . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo, Mean . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (23) | 1 | NF-pNET | N/A | Head | 9 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | N/A |

| (29) | 1 | NF-pNET | G2 | Tail | 20 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | 1 |

| (30) | 2 | NF-pNET | N/A | 2, Head | 27.5 (15–40) | 1–2 | None | Change in vascularity, central necrosis area 15 mm (2/2) | 1 |

| (31) | 3 | Insulinoma | N/A | 2, Head | 18 (14–22) | 1 | None | PR, symptom improved (3/3) | 12 |

| 1, Body | |||||||||

| (32) | 8 | NF-pNET (7) | G1 (1) | 3, Head | 19 (8–28) | 1–3 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (6/8) | 13 |

| Insulinoma (1) | G2 (1) | 5, Body | Abdominal pain (1) | IR (2/8) | |||||

| N/A (6) | |||||||||

| (33) | 14 | NF-pNET | G1 | 3, Head | 13.1 (10–20) | 1 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (12/14) | 12 |

| 6, Body | MPD stenosis (1) | IR (2/14) | |||||||

| 5, Tail | |||||||||

| (34) | 1 | Insulinoma | G1 | Body | 12 | N/A | Fever | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 2 |

| (35) | 3 | Insulinoma (2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | None | CR (N/A) | N/A |

| Vipoma (1) | Symptoms resolution (3/3) | ||||||||

| (36) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Uncinate | 18 | 3 | None | CR, symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| (37) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Body | 10 | 1 | None | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| Our study | 27 | Insulinoma (7) | G1 (15) | 10, Head | 14.3 (4.5–30) | 1 | Mild pancreatitis (2) | CR (26/27) | 8.7 |

| G3 (2) | 8, Body | IR (1/27) | |||||||

| 5, Uncinate | Symptoms resolution (7/7) | ||||||||

| 2, Tail | |||||||||

| 1, Liver metastasis | |||||||||

| 1, Lymph node metastasis |

Abbreviation: G1, Grade 1; G3, Grade 3; IR, incomplete response (no change in size or decrease in diameter < 50 %.); N/A, not available; PR, partial response.

Summary of the Literature Regarding EUS-RFA Outcomes for pNETs Patients, Including Our Data

| Study . | Lesions, n . | Tumor Functionality . | Grade . | Lesion: n, Location . | Mean Size, mm (Range) . | Number of Ablation Sessions . | Complications . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo, Mean . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (23) | 1 | NF-pNET | N/A | Head | 9 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | N/A |

| (29) | 1 | NF-pNET | G2 | Tail | 20 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | 1 |

| (30) | 2 | NF-pNET | N/A | 2, Head | 27.5 (15–40) | 1–2 | None | Change in vascularity, central necrosis area 15 mm (2/2) | 1 |

| (31) | 3 | Insulinoma | N/A | 2, Head | 18 (14–22) | 1 | None | PR, symptom improved (3/3) | 12 |

| 1, Body | |||||||||

| (32) | 8 | NF-pNET (7) | G1 (1) | 3, Head | 19 (8–28) | 1–3 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (6/8) | 13 |

| Insulinoma (1) | G2 (1) | 5, Body | Abdominal pain (1) | IR (2/8) | |||||

| N/A (6) | |||||||||

| (33) | 14 | NF-pNET | G1 | 3, Head | 13.1 (10–20) | 1 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (12/14) | 12 |

| 6, Body | MPD stenosis (1) | IR (2/14) | |||||||

| 5, Tail | |||||||||

| (34) | 1 | Insulinoma | G1 | Body | 12 | N/A | Fever | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 2 |

| (35) | 3 | Insulinoma (2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | None | CR (N/A) | N/A |

| Vipoma (1) | Symptoms resolution (3/3) | ||||||||

| (36) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Uncinate | 18 | 3 | None | CR, symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| (37) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Body | 10 | 1 | None | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| Our study | 27 | Insulinoma (7) | G1 (15) | 10, Head | 14.3 (4.5–30) | 1 | Mild pancreatitis (2) | CR (26/27) | 8.7 |

| G3 (2) | 8, Body | IR (1/27) | |||||||

| 5, Uncinate | Symptoms resolution (7/7) | ||||||||

| 2, Tail | |||||||||

| 1, Liver metastasis | |||||||||

| 1, Lymph node metastasis |

| Study . | Lesions, n . | Tumor Functionality . | Grade . | Lesion: n, Location . | Mean Size, mm (Range) . | Number of Ablation Sessions . | Complications . | Response . | Follow-Up, Mo, Mean . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (23) | 1 | NF-pNET | N/A | Head | 9 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | N/A |

| (29) | 1 | NF-pNET | G2 | Tail | 20 | 1 | None | CR (1/1) | 1 |

| (30) | 2 | NF-pNET | N/A | 2, Head | 27.5 (15–40) | 1–2 | None | Change in vascularity, central necrosis area 15 mm (2/2) | 1 |

| (31) | 3 | Insulinoma | N/A | 2, Head | 18 (14–22) | 1 | None | PR, symptom improved (3/3) | 12 |

| 1, Body | |||||||||

| (32) | 8 | NF-pNET (7) | G1 (1) | 3, Head | 19 (8–28) | 1–3 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (6/8) | 13 |

| Insulinoma (1) | G2 (1) | 5, Body | Abdominal pain (1) | IR (2/8) | |||||

| N/A (6) | |||||||||

| (33) | 14 | NF-pNET | G1 | 3, Head | 13.1 (10–20) | 1 | Pancreatitis (1) | CR (12/14) | 12 |

| 6, Body | MPD stenosis (1) | IR (2/14) | |||||||

| 5, Tail | |||||||||

| (34) | 1 | Insulinoma | G1 | Body | 12 | N/A | Fever | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 2 |

| (35) | 3 | Insulinoma (2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | None | CR (N/A) | N/A |

| Vipoma (1) | Symptoms resolution (3/3) | ||||||||

| (36) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Uncinate | 18 | 3 | None | CR, symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| (37) | 1 | Insulinoma | N/A | Body | 10 | 1 | None | Symptoms resolution (1/1) | 10 |

| Our study | 27 | Insulinoma (7) | G1 (15) | 10, Head | 14.3 (4.5–30) | 1 | Mild pancreatitis (2) | CR (26/27) | 8.7 |

| G3 (2) | 8, Body | IR (1/27) | |||||||

| 5, Uncinate | Symptoms resolution (7/7) | ||||||||

| 2, Tail | |||||||||

| 1, Liver metastasis | |||||||||

| 1, Lymph node metastasis |

Abbreviation: G1, Grade 1; G3, Grade 3; IR, incomplete response (no change in size or decrease in diameter < 50 %.); N/A, not available; PR, partial response.

Radiofrequency use, causing controlled thermocoagulative necrosis of the target lesions, has been successfully implemented as a locally ablative technique in the treatment of primary, solid tumors in various organs, including ablation of liver neuroendocrine metastases (38–44). The application of RFA, using a percutaneous or laparotomy approach for treatment of pancreatic lesions, presented with technical challenges related to anatomical constraints and properties of the pancreatic parenchyma, and consequently led to slower adoption of RFA for pancreatic tumors. Given the proximity of many vital structures to the pancreas, the risk of thermal injury to the major vessels, MPD, distal common bile duct, duodenum, transverse colon, and portal vein is considerable. Moreover, as a result of the high thermosensitivity of normal pancreatic tissue, major complications were unacceptably high, including acute necrotizing pancreatitis, pancreatic leaks, infection of necrotic pancreatic tissue, and post-treatment bleeding (45, 46). As a consequence of the adoption of EUS-RFA, with its minimally invasive nature, accessibility to all areas of the pancreas, real-time visualization of the needle-probe placement, and other technical advances, the rates of complications from RFA application in the pancreas have decreased significantly.

The first prospective study [Rossi et al. (23)] on RFA for the treatment of pNETs included 10 noneligible or unwilling to undergo surgery patients (NF-pNET, n = 7; insulinoma, n = 2; gastrinoma, n = 1). RFA procedures were successfully performed using three approaches: percutaneous, intraoperative, and under EUS guidance in six, three, and one cases, respectively. Complications were observed in three patients (percutaneous, n = 1; intraoperative, n = 2), all including acute pancreatitis with subsequent pancreatic fluid collections requiring endoscopic drainage in two patients. There were no recurrences at a median follow-up of 34 months (23).

Additional reports described successful treatment with EUS-RFA of NF-pNETs: one patient with a 2-cm lesion located in the pancreatic tail [Armellini et al. (29)] and another two patients with tumors both located in the pancreatic head, with a mean size of 27.5 mm [Pai et al. (30)]. In both reports, no immediate postprocedural complications were observed (29, 30).

Lakhtakia et al. (31) reported three insulinoma patients having symptomatic hypoglycemia who underwent EUS-RFA with rapid symptomatic and biochemical resolution within 48 hours after the procedure and a sustained response at 12 months follow-up. A series of seven NF-pNETs and one insulinoma were detailed in a study by Choi et al. (32). All patients were treated with EUS-RFA as a result of ineligibility for or refusal of surgery. Among the seven patients with NF-pNETs, a CR on imaging studies was observed in five patients, whereas two had persistent NETs. The patient with insulinoma showed complete clinical response in terms of the hypoglycemia-related symptoms. Recently, EUS-RFA, for the treatment of small pNETs and pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN), was evaluated in a prospective multicenter study [Barthet et al. (33)]. The study objectives were to assess safety and efficacy of the procedure based on a 1-year follow-up. In an overall cohort of 29 patients, three adverse events (10%) occurred, two of them reported in patients with pNETs. Among 12 patients with 14 pNET lesions (mean size 13.1 mm), a complete tumor resolution was reported in 12 (86%) lesions at a 1-year follow-up. Finally, a number of additional case studies and preliminary reports contribute to the growing body of evidence in regard to the relevance of the EUS-RFA procedure in the treatment repertoire of patients with functional, indolent pNETs (34–37).

In conclusion, within the limitations of its retrospective nature, heterogeneous cohort, and a relatively short-length of follow-up, our series shows that EUS-RFA is a relatively safe and effective treatment modality in selected patients with pNETs. Prospective multicenter-randomized studies, including a larger number of pNET patients, and the comparison of EUS-RFA with other established approaches would be optimal for defining the best candidates for therapies, treatment timing, or its efficacy in terms of tumor response and long-term survival. However, as a result of the rarity of these tumors, as well as the limited availability of centers with experience in RFA, until such trials will be available, clinicians who manage these patients will most probably have to rely on personal experience and data from retrospective studies.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- 68Ga-DOTATATE

gallium 68-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid-octreotate

- CECT

contrast enhanced spiral CT

- CR

complete response

- EUS-RFA

endoscopic ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation

- G

grade

- MEN1

multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1

- MPD

main pancreatic duct

- NF-pNET

nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

- PET

positron emission tomography

- pNEN

pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm

- pNET

pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

References and Notes

Author notes

K.O. and A.D. share first authorship. H.J. and S.G.-G. share senior authorship.