-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yacouba L. Diallo, Véronique Ollivier, Véronique Joly, Dorothée Faille, Giovanna Catalano, Martine Jandrot-Perrus, Antoine Rauch, Patrick Yeni, Nadine Ajzenberg, Abacavir has no prothrombotic effect on platelets in vitro, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 71, Issue 12, 1 December 2016, Pages 3506–3509, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw303

Close - Share Icon Share

HIV patients exposed to abacavir have an increased risk of myocardial infarction, with contradictory results in the literature. The aim of our study was to determine whether abacavir has a direct effect on platelet activation and aggregation using platelets from healthy donors and from HIV-infected patients under therapy with an undetectable viral load.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or whole blood from healthy donors was treated with abacavir (5 or 10 μg/mL) or its active metabolite carbovir diphosphate. Experiments were also performed using blood of HIV-infected patients (n = 10) with an undetectable viral load. Platelet aggregation was performed on PRP by turbidimetry and under high shear conditions at 4000 s−1. Platelet procoagulant potential was analysed by measuring thrombin generation by thrombinography.

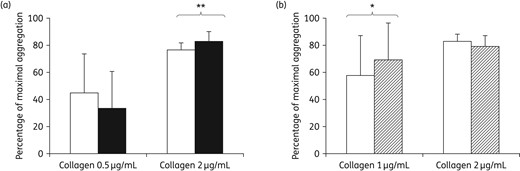

Abacavir and carbovir diphosphate significantly increased the aggregation of platelets from healthy donors induced by collagen at 2 μg/mL (P = 0.002), but not at 0.5 μg/mL. No effect of abacavir or carbovir diphosphate was observed on platelet aggregation induced by other physiological agonists or by high shear stress, or on thrombin generation. Pretreatment of blood from HIV-infected patients with abacavir produced similar results.

Our results suggest that abacavir does not significantly influence platelet activation in vitro when incubated with platelets from healthy donors or from HIV-infected patients. It is, however, not excluded that a synergistic effect with other drugs could promote platelet activation and thereby play a role in the pathogenesis of myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Alongside the decline in HIV-related mortality, large-scale studies conducted in Europe and the USA have shown a 50%–100% increased risk of myocardial infarction after adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors. The potential contribution of NRTIs to myocardial infarction has been the subject of some controversy. Within the D:A:D (‘Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs’) study an increased risk for myocardial infarction was reported in patients being treated with abacavir or exposed to this drug within the preceding 6 months.1 These findings were confirmed by some studies,2 but not others, including a meta-analysis of published and unpublished data.3

A potential mechanism for an increased risk of myocardial infarction could be related to platelet activation. Indeed, platelets play a crucial role in arterial thrombosis particularly in myocardial infarction.4 Platelet activation occurs in high shear rate conditions as in stenotic arteries and also in inflamed vessels as reported in HIV-infected patients.5,6 Activated platelets secrete soluble agonists, ADP and thromboxane A2, that recruit additional platelets and promote clot stabilization. Activated platelets also expose anionic phospholipids on their surface, which allow the assembly of coagulation proteins and thrombin generation.

Abacavir is used in combination ART (cART) for HIV treatment. Once inside the cell, abacavir is transformed into active carbovir diphosphate via phosphorylation by cellular kinases.7 No data on platelet metabolism by abacavir are available. Additionally, abacavir was reported to increase leucocyte adhesion to endothelium in vitro8 without exerting a direct effect on endothelial activation.9–11

Because of these contradictory results reported in the literature about the eventual role of abacavir in myocardial infarction, we investigated whether abacavir and its activated metabolite carbovir diphosphate have a direct effect on platelet activation and aggregation, as well as on thrombin generation, by in vitro studies using platelets from healthy donors and from HIV-infected patients under therapy with an undetectable viral load.

Methods

Patients and controls

Ten HIV-infected patients with an undetectable viral load (<50 copies/mL) for at least 2 months were prospectively recruited between October 2010 and December 2011 at the Department of Infectious Diseases, Bichat Hospital, Paris. The patients had not received abacavir and were free of anti-aggregant (aspirin and/or clopidogrel) or anticoagulant treatment. None of them had a chronic hepatitis B or C infection. One patient had a cured hepatitis C infection. Healthy donors who had taken no medication during the previous 2 weeks were recruited as controls. A local ethics committee approved the study and all patients and controls provided informed consent to the research protocol.

Platelet studies

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (300 G/L) from healthy donors prepared as previously described12 was pre-incubated for 15 min with abacavir (Toronto Research Chemicals, Canada) (5 μg/mL) or for 1 h with its active metabolite carbovir diphosphate (200 ng/mL) (Hartman Analytic Bioactif, France) at room temperature with gentle agitation. In other experiments, whole blood from healthy donors was pre-incubated with abacavir (10 μg/mL) or carbovir diphosphate (200 ng/mL) for 2 h at room temperature and PRP was prepared. In all conditions, buffer controls were performed under the same incubation conditions using PBS.

Whole blood from HIV-infected patients with an undetectable viral load was pre-incubated with abacavir (10 μg/mL) or PBS for 2 h at room temperature and PRP was prepared.

Agonist-induced platelet aggregation, including collagen, ADP, arachidonic acid or ristocetin, was studied in PRP by light transmittance aggregometry as previously reported.12

Shear-induced platelet aggregation was measured as previously described12 at 4000 s−1 in PRP pre-incubated with abacavir (10 μg/mL) or carbovir diphosphate (200 ng/mL) or PBS.

Thrombin generation was measured in PRP (150 G/L) and in platelet-poor plasma (PPP) by means of a calibrated automated thrombogram (CAT®, Diagnostica Stago, Asnières, France) as previously reported.13

Statistical analysis

Each experimental point was performed in duplicate. Results from at least three experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analysed using PRISM (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). P values were calculated using a paired Student's t-test. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

(a) Collagen-induced platelet aggregation in PRP (300 G/L) from healthy donors (n = 4) incubated with abacavir (10 μg/mL) for 2 h at room temperature with gentle agitation (black bars) or with PBS in the same conditions (white bars). (b) Collagen-induced platelet aggregation at 1 and 2 μg/mL in PRP from HIV-infected patients incubated with abacavir. Whole blood from HIV-infected patients (n = 10) with an undetectable viral load was incubated for 2 h with abacavir (10 μg/mL) at room temperature with gentle agitation (hatched bars) or with PBS in the same conditions (white bars). Results are expressed as the percentage of maximal aggregation. **P = 0.002. *P = 0.003.

Thrombin generation curves were similar both in PRP and in PPP when comparing abacavir- and carbovir diphosphate-treated samples with control conditions using the calibrated automated thrombogram (Figure S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

In order to determine whether a prothrombotic effect could occur preferentially in HIV-infected patients, we pre-incubated abacavir (10 μg/mL) in whole blood of HIV-infected patients with an undetectable viral load.

The clinical characteristics of the 10 patients are summarized in Table 1. Two of them had been treated for hypertension and none of them had a history of thrombotic events. In all patients, cART had been initiated for more than 8 months and viral load had been undetectable for at least 8 months.

| Patient number . | Age (years) . | cART regimen . | Cardiovascular risk factor . | CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 183 |

| 2 | 26 | Truvada + Kaletra + Invirase + raltegravir | none | 258 |

| 3 | 46 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir + raltegravir | hypertension | 299 |

| 4 | 36 | Atripla | none | 209 |

| 5 | 41 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 182 |

| 6 | 41 | Atripla | none | 463 |

| 7 | 44 | Atripla | none | 210 |

| 8 | 39 | Atripla | hypertension | 261 |

| 9 | 57 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 258 |

| 10 | 40 | Atripla | none | 543 |

| Patient number . | Age (years) . | cART regimen . | Cardiovascular risk factor . | CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 183 |

| 2 | 26 | Truvada + Kaletra + Invirase + raltegravir | none | 258 |

| 3 | 46 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir + raltegravir | hypertension | 299 |

| 4 | 36 | Atripla | none | 209 |

| 5 | 41 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 182 |

| 6 | 41 | Atripla | none | 463 |

| 7 | 44 | Atripla | none | 210 |

| 8 | 39 | Atripla | hypertension | 261 |

| 9 | 57 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 258 |

| 10 | 40 | Atripla | none | 543 |

Truvada = emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; Prezista = darunavir; Norvir = ritonavir; Kaletra = lopinavir and ritonavir; Invirase = saquinavir mesilate; Atripla = efavirenz, emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

| Patient number . | Age (years) . | cART regimen . | Cardiovascular risk factor . | CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 183 |

| 2 | 26 | Truvada + Kaletra + Invirase + raltegravir | none | 258 |

| 3 | 46 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir + raltegravir | hypertension | 299 |

| 4 | 36 | Atripla | none | 209 |

| 5 | 41 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 182 |

| 6 | 41 | Atripla | none | 463 |

| 7 | 44 | Atripla | none | 210 |

| 8 | 39 | Atripla | hypertension | 261 |

| 9 | 57 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 258 |

| 10 | 40 | Atripla | none | 543 |

| Patient number . | Age (years) . | cART regimen . | Cardiovascular risk factor . | CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 183 |

| 2 | 26 | Truvada + Kaletra + Invirase + raltegravir | none | 258 |

| 3 | 46 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir + raltegravir | hypertension | 299 |

| 4 | 36 | Atripla | none | 209 |

| 5 | 41 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 182 |

| 6 | 41 | Atripla | none | 463 |

| 7 | 44 | Atripla | none | 210 |

| 8 | 39 | Atripla | hypertension | 261 |

| 9 | 57 | Truvada + Prezista + Norvir | none | 258 |

| 10 | 40 | Atripla | none | 543 |

Truvada = emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; Prezista = darunavir; Norvir = ritonavir; Kaletra = lopinavir and ritonavir; Invirase = saquinavir mesilate; Atripla = efavirenz, emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

As observed with healthy controls, a moderately significant increasing effect of abacavir was obtained on collagen-induced platelet aggregation at 1 μg/mL only (Figure 1b). Abacavir had no effect on other agonist-induced platelet aggregation (data not shown).

Discussion

An increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with abacavir treatment is the subject of clinical and biological debate.

In our study we demonstrated that abacavir only moderately increased platelet aggregation induced by collagen (2 μg/mL). It had no effect on platelet aggregation induced by other agonists or by a high shear rate of 4000 s−1 that mimics stenotic arteries.

In contrast, most of the other previous studies have reported increased platelet aggregation with different agonists [ADP, collagen, epinephrine and thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP)] in HIV-infected patients treated with abacavir.14,15 However, the concentration of agonists used in the Satchell et al.14 study was around 5- to 10-fold higher than the ones we used in our study and the one required to treat patients. Also, the abacavir concentration (80 μg/mL) was more than 10-fold higher than the plasmatic concentration obtained in abacavir-treated patients, with a rather moderate effect. As abacavir could require intracellular metabolism to be active in platelets, we tested the effect of its active metabolite, carbovir diphosphate. A similar effect of carbovir diphosphate compared with abacavir was observed on platelet activation and aggregation in healthy donors. It significantly increased the platelet aggregation induced by collagen (2 μg/mL) by ∼5%. Even though significant, this effect remained modest and was unlikely to have a physiopathological impact.

One potential mechanism by which abacavir could enhance platelet activation and aggregation is via the competitive inhibition of soluble guanylyl cyclase.16 We did not observe any competitive effect of abacavir or carbovir diphosphate on soluble guanylyl cyclase in our experimental conditions as phosphorylation of vasodilatator-stimulated phosphoprotein was not impaired (data not shown).

Moreover, we did not observe any effect of abacavir or carbovir diphosphate on thrombin generation assessed in either PPP or PRP. Our results are similar to those reported by Jong et al.,17 as no specific abnormalities in coagulation or inflammation parameters were observed in abacavir-treated patients.

We investigated the effect of abacavir on platelet aggregation in 10 HIV-infected patients with an undetectable viral load under abacavir-free cART. We reproduced the same moderate effect of abacavir on platelet aggregation induced by 1 μg/mL collagen only. In one study an increased platelet aggregation induced by ADP, TRAP and collagen in the HIV population was obtained, compared with non-HIV-infected patients.14 It is notable that most studies have been performed in patients treated with abacavir combined with other antiretroviral drugs that could modify the effect of abacavir on platelets. The chronic inflammatory state associated with HIV infection could also promote platelet activation and aggregation independently of any treatment, by release of proinflammatory cytokines.15 In our study, patients experienced controlled HIV replication. This may have reduced their inflammatory state, and prevented abacavir exerting an activating effect on platelet aggregation.

In conclusion, our results suggest that abacavir does not significantly influence in vitro platelet aggregation when incubated with platelets from healthy donors or from HIV-infected patients. Because abacavir is frequently associated in therapeutic combination with other antiretroviral drugs, we cannot exclude that a synergistic effect with other drugs could promote platelet activation and thereby play a role in the pathogenesis of myocardial infarction.

Funding

This work was supported by Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Author contributions

N. A., V. J. and P. Y. participated in the conception and design of the study. Y. L. D., D. F., M. J.-P., V. O., A. R. and N. A. analysed and interpreted the data. G. C., P. Y., V. J., Y. L. D. and N. A. provided study materials or recommended patients. Y. L. D. and N. A. performed statistical analysis. Y. L. D., N. A. and P. Y. wrote the article. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

References