-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rosie Nash, Derek Choi-Lundberg, Claire Eccleston, Shandell Elmer, Gina Melis, Tracy Douglas, Melanie Eslick, Laura Triffett, Carey Mather, Hazel Maxwell, Romany Martin, Phu Truong, Jonathon Sward, Karen Watkins, Marie-Louise Bird, Measuring health professionals’ capability to respond to health consumers’ health literacy needs: a scoping review, Health Promotion International, Volume 39, Issue 6, December 2024, daae171, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daae171

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Health literacy-responsive health professionals will be increasingly important in addressing healthcare access and equity issues. This international scoping review aims to understand the extent and ways in which health professionals respond to healthcare users’ health literacy, identifying tools used to measure health literacy responsiveness and training to support the development of these attributes. Four online databases were searched. Using Covidence software and pre-determined inclusion/exclusion criteria, all articles were screened by two authors. Data were extracted using a researcher-developed data extraction tool. From the 1531 studies located, 656 were screened at title and abstract and 137 were assessed at full text; 68 studies met the inclusion criteria and 61 were identified through hand searching resulting in 129 papers in total. Five overlapping thematic elements describing thirty attributes of health literacy responsive health professionals were identified: (i) communication, (ii) literacies, (iii) andragogy, (iv) social/relational attributes and (v) responding to diversity. Other concepts of ‘tailoring’ and ‘patient-centred care’ that cut across multiple themes were reported. Forty-four tools were identified that assessed some aspects of health literacy responsiveness. Thirty of the tools reported were custom tools designed to test an intervention, and 14 tools were specifically employed to assess health literacy responsiveness as a general concept. Seventy studies described education and training for health professionals or students. This scoping review provides a contemporary list of key attributes required for health literacy-responsive health professionals, which may serve as a foundation for future health literacy research including the development of curricula in health professional education and tools to measure health professional health literacy responsiveness.

Health professionals who have health literacy responsive attributes will optimize health promotion efforts to patient’s health literacy strengths and challenges.

This contemporary list of measurable elements and attributes of health literacy responsiveness will guide health professional education and training.

These 5 thematic elements and 14 existing tools provide the foundation for the future development of a comprehensive assessment tool.

INTRODUCTION

Health literacy is essential for supporting the health of individuals and societies. A contemporary view of health literacy includes attributes related to an individual, their community and the health system with which they interact (Sørensen et al., 2021). Individual health literacy is described as

the personal characteristics and social resources needed for individuals and communities to access, understand, appraise and use information and services to make decisions about health. (Dodson, 2015, p. 12)

From a societal and health system equity perspective, organizational health literacy responsiveness includes service provision that meets the diverse health literacy needs of people. Attributes related to communication, culture, leadership and workforce development, policies and practice should be considered in organizational health literacy (Chu et al., 2024).

Hence, health literacy is a complex construct that involves the interplay between individuals, communities and organizations within the health system and society. The role of individual health professionals within health literacy-responsive organizations is critically important but has been examined less than organizational constructs (Sørensen et al., 2012).

A health literate and health literacy-responsive health workforce are required to meet the needs of people seeking and utilizing health services, and to empower users of these services to take greater control over their health. Health professionals and their clients are involved in multiple exchanges of information and resources, which can be enhanced by a health professional who is astute to the needs of their client and skilled at adjusting their approach with each new encounter. The future health workforce requires explicit training in the ability to respond to the health literacy needs of their clients especially considering high rates of chronic health conditions, misinformation/disinformation and the impact of social determinants on the health status of people and communities (Saunders et al., 2019).

Preparing health professionals to support and be responsive to the health literacy needs of healthcare users has appeared in curricula in higher income countries (Coleman et al., 2013) and is an identified priority (Coleman, 2011; Nutbeam and Lloyd, 2021). Health professional health literacy competencies have been classified into knowledge, skills, practices and attitudes (Coleman et al., 2013; Cesar et al., 2022). Whilst health literacy competencies have been explored, a wholistic and contemporary understanding of the attributes of a health literacy-responsive health professional is yet to be identified and is the focus of this review. Health literacy practices internationally reflect differences in health systems and training, and a geographical comparison of publications from different regions is warranted to examine equity.

Evaluation of health professional health literacy responsiveness is problematic, as there is no existing comprehensive validated measurement instrument to monitor health professionals’ development of health literacy responsiveness (knowledge, skills and attitudes) over time (Laing et al., 2020). However, several tools have been developed to measure the effectiveness of interventions designed to upskill health professionals, for example, for migrant health (Centre for Culture, Ethnicity and Health, 2016) and health literacy communication programmes (Kaper et al., 2018). These pilot studies are relatively narrow in their ability to measure health literacy responsiveness and are often focused on the opinions of health care users with respect to health professionals or organizations. Given the importance of developing a health literacy-responsive workforce, it is timely to consider reviewing the literature and developing a comprehensive and contemporary list of attributes to inform the development of a tool that reflects the evolution of health literacy and the key attributes required to be health literacy-responsive health professionals.

This scoping literature review was warranted to identify and collate existing instruments, support the collation of the key attributes, related conceptual frameworks and constructs to inform curricula and the development of a comprehensive tool to measure health professional health literacy responsiveness. This review type was seen as most appropriate as it supports the collation and synthesis of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods findings and supported the researchers to summarize existing conceptual frameworks and constructs and identify gaps in the literature (Grant and Booth, 2009). This review is inclusive of health professionals, health workers and students in these disciplines: medicine, midwifery, nursing, occupational therapy, paramedicine, pharmacy, physiotherapy, psychology and public health. The attributes of health literacy responsiveness that should be included in entry-to-practice curricula and post-graduate professional development remains a gap in the literature that this review aims to address.

The objective of this scoping review was to assess the literature that describes ways in which health professionals’ health literacy responsiveness may be best developed and measured. Specifically, the research questions this review addressed were:

What are the measurable elements and attributes of health literacy responsiveness required of health professionals or health professional students?

What tools exist to measure health professionals’ or health professional students’ health literacy responsiveness?

What important measurable elements and attributes are included in the education and training of health professionals or health professional students to ensure they are responsive to health care users’ health literacy?

METHODS

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology (Page et al., 2021). A protocol of this review is publicly available on the Open Science Framework (Bird et al., 2022). This review maps elements and attributes of health literacy responsiveness described in the literature for health professionals and students undertaking study in health disciplines.

Search terms

The research questions outlined informed the identification of keywords, which were arranged following the Population, Concept, Context framework (Supplementary Table 1). The population included health professionals and students undertaking study in health disciplines. The concept of interest was the measurable elements and attributes of health literacy responsiveness that are enacted by health professionals. The contexts include various healthcare settings and organizations and tertiary and vocational training.

Search strategy

A preliminary search of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Synthesis was conducted in January 2022 at which time no current or underway systematic reviews or scoping reviews on this topic were identified. A pilot search of Web of Science and MEDLINE was then undertaken (January 2022) to identify articles on the topic. Text words contained in titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and index terms used to describe articles were used to refine the search strategy in discussion with the review team and consultation with a research librarian. The pilot and final search strategies are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Four databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Scopus) were searched by one author (G.M.) on 22 April 2022. The search strategy was adapted for each database. References were imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) for screening and full text review. In Covidence, all papers were reviewed against the inclusion/exclusion criteria at the title, abstract and then full-text level by two independent reviewers. Where consensus was not met a third reviewer determined with the two original reviewers whether to include or exclude. The reference lists of all included sources of evidence were screened for additional studies.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Publications in this review were in peer-reviewed full-text journals, written in English, from 2008 to 2022 that reported on health professionals or students undertaking study in health disciplines. Inclusion and exclusion details are provided in Supplementary Table 3. Articles that described tools or training for health literacy responsiveness for health professionals were included. Health professionals who worked in public and private organizations or studies that described training of health professionals were also included. Studies not published in English were excluded as there were limited resources for translation. The justification of the start date reflects the changes in definitions of health literacy since 2008, which would mean that data before this time would have less contemporary relevance (Sørensen, 2019).

Studies that used questionnaires, surveys or interviews to measure health professional responsiveness were included. Papers that described education for health professionals to be responsive to their clients’ health literacy either for entry to practice undergraduate programmes, post-graduate programmes or as part of professional development activities were also included. Studies that measured an individual’s health literacy or organizational health literacy responsiveness were intentionally excluded.

Data extraction

To ensure rigour, data were extracted by two or more independent reviewers using a standardized extraction form. The extracted data included demographic information about the studies (e.g. location of research, study design, context and included professions) as well as the data required to answer all three research questions. Any data extraction concerns were discussed between the reviewers before extraction was finalized, and any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Data extraction was completed between 7 December 2022 and 4 April 2023. Following data extraction, researchers reviewed the extraction tables to ensure clarity and consistency of data reporting.

Data analysis and presentation

This review uses the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018). Inductive content analysis was utilized (Kyngäs, 2020; Vears and Gillam, 2022), the stages of which include (i) decontextualization, (ii) recontextualization, (iii) categorization and (iv) compilation (Bengtsson, 2016). This method of qualitative data analysis is helpful when research outcomes are intended to inform practical answers or applications. The analysis commenced with a preset extraction template (deductive coding), developed based on expert opinion and available literature, which was expanded to include additional themes and categories of responsiveness as they were identified during the search (inductive coding). The extraction template used a checklist; where the categories did not fit, a free text option was available to further inform the inductive development of new themes and categories. Data are presented in a tabulated form, with elements found in this review that describe the attributes health professionals need to have to respond to their healthcare users’ health literacy. As well as the range of attributes identified, frequency of occurrence in the literature is presented.

Data were analysed in Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests (if one or more expected values were five or less) were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) to compare the number of papers with particular health literacy responsiveness (HLR) elements that described HLR education versus had not described HLR education. Additionally, to address the evident predominance of papers with authors from the USA, these tests also compared papers with authors from the USA versus rest of the world. The p value considered significant was adjusted by the Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05/30 = 0.002), but elements with p < 0.05 are also noted.

RESULTS

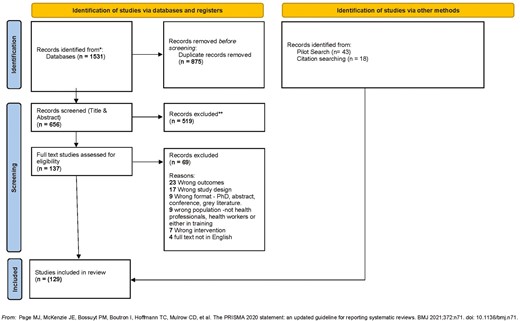

From the 1531 studies located, 656 were screened at title and abstract and 137 were assessed at full text; 68 studies met the inclusion criteria. Forty-three studies were identified from the pilot search, and an additional 18 from searching references of included studies, for a total of 129 studies included in the review (see Figure 1). A comprehensive data extraction table that links the following data to each paper is provided in Supplementary Table 4. The associated full reference list is accessible in Supplementary Table 5.

Geographic regions and countries of included publications

Countries of the included publications (authors’ affiliations and where the studies were conducted) were tallied and classified by geographic region. Most publications were from the Americas (n = 76, 59%), with smaller numbers from Oceania (n = 20, 16%), Asia and Europe (each n = 18, 14%) and Africa (n = 3, 2%). By country, the majority of publications were from the USA (n = 70, 54%), followed by Australia (n = 18, 14%), the Netherlands (n = 8, 6%) and the UK (n = 7, 5%) (Supplementary Table 6).

Study designs

Papers were classified as per the evidence hierarchy (Weeraratne et al., 2010) with 10 (8%) Level I reviews, 3 (2%) Level II randomized controlled trials, 2 (2%) Level III comparative studies, 86 (67%) Level IV case series and 28 (22%) Level V opinion pieces, editorials or discussion papers. Papers were also classified as mixed methods (n = 33, 26%), qualitative (n = 74, 57%) or quantitative (n = 22, 17%).

Study context

The study contexts included primary healthcare (n = 57, 44%), hospitals (n = 39, 30%), academic medical centres (n = 11, 9%), care facilities (n = 4, 3%), universities (n = 33, 26%), conferences (n = 8, 6%) and training sessions at non-specified locations (n = 2, 2%). The total exceeds the number of studies (n = 129) as many studies included more than one context.

Study populations

The study populations of articles included health professionals (n = 93, 72%), healthcare workers (n = 25, 19%), healthcare students (n = 37, 29%), patients or clients or healthcare users (n = 30, 23%) and/or other (n = 22, 17%). The majority of articles (n = 75, 58%) included only one of these categories, while the others included two or more population categories. The ‘other’ population category included community members or leaders (n = 2, 2%); educators, academics, researchers, managers or administrators (n = 20, 16%) and/or other professionals (n = 3, 2%).

The most frequently represented professions (including students) in the articles were nursing/midwifery (n = 77, 60%), medical practitioners (n = 66, 51%) and pharmacy (n = 30, 23%). Numerous other categories of health professionals and health workers were also represented in the articles (Supplementary Table 7). While the majority (n = 68, 53%) of articles involved health professionals or health workers in only one category, 13 articles (10%) had two categories, 15 (12%) had three categories and 33 (26%) had four or more categories.

Excluding review articles, 110 of the papers reported the number of participants, with a total of over 43 400 participants, ranging from 2 to 20 000 participants (median 78).

Research Q1. What are the measurable elements and attributes of health literacy responsiveness required of health professionals or health professional students?

Using deductive coding, five thematic elements describing 30 attributes of health literacy-responsive health professionals were identified. First, communication as a thematic element had four sub-themes: general, plain, bidirectional and multimodal communication. Second, the thematic element literacies included health, general and digital literacy capabilities and their assessment. The third thematic element of andragogy was used to describe both the provision of information (teaching) and checking for understanding. The ability of health professionals to respond to diversity was the fourth thematic element and social and relational elements were the fifth. The frequency of these elements is described in Table 1.

Health literacy responsiveness elements identified in papers organized by themes and sub-themes, and for papers with or without authors from the USA

| All papers (n = 129) . | Countries of authors . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Percentage (number) . | USAa (n = 70) . | Did not include USA (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | |||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 44% (57) | 34% (24) * | 56% (33) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy and/or numeracy | 20% (26) | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 7% (9) | 4% (3) | 10% (6) | ||

| Andragogy | |||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 19% (25) | 27% (19) ** | 10% (6) | |

| Demonstrations | 11% (14) | 10% (7) | 12% (7) | ||

| Underlining key information | 11% (14) | 17% (12) ** | 3% (2) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 58% (75) | 74% (52) *** | 39% (23) | |

| Chunk & Check | 8% (10) | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | |||||

| General | Provide information | 52% (67) | 51% (36) | 53% (31) | |

| Open-ended questions | 18% (23) | 19% (13) | 17% (10) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 74% (96) | 76% (53) | 73% (43) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 62% (80) | 69% (48) | 54% (32) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 30% (39) | 40% (28) ** | 19% (11) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 29% (37) | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 33% (43) | 30% (21) | 37% (22) | |

| Ask Me 3 (questions for client to ask provider) | 5% (7) | 10% (7) ** | 0% (0) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (51) | 41% (29) | 37% (22) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 13% (17) | 10% (7) | 17% (10) | ||

| Read aloud | 9% (11) | 9% (6) | 8% (5) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (4) | 4% (3) | 2% (1) | ||

| Respond to diversity | |||||

| Cultural awareness | 29% (37) | 26% (18) | 32% (19) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 26% (33) | 26% (18) | 25% (15) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 19% (25) | 10% (7)* | 31% (18) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 5% (6) | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | |||||

| Shared decision making (individual and community) | 19% (24) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Empowerment | 18% (23) | 10% (7)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Trust | 13% (17) | 6% (4)* | 22% (13) | ||

| Respect | 12% (16) | 10% (7) | 15% (9) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 12% (16) | 9% (6) | 17% (10) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 12% (15) | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

| All papers (n = 129) . | Countries of authors . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Percentage (number) . | USAa (n = 70) . | Did not include USA (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | |||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 44% (57) | 34% (24) * | 56% (33) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy and/or numeracy | 20% (26) | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 7% (9) | 4% (3) | 10% (6) | ||

| Andragogy | |||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 19% (25) | 27% (19) ** | 10% (6) | |

| Demonstrations | 11% (14) | 10% (7) | 12% (7) | ||

| Underlining key information | 11% (14) | 17% (12) ** | 3% (2) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 58% (75) | 74% (52) *** | 39% (23) | |

| Chunk & Check | 8% (10) | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | |||||

| General | Provide information | 52% (67) | 51% (36) | 53% (31) | |

| Open-ended questions | 18% (23) | 19% (13) | 17% (10) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 74% (96) | 76% (53) | 73% (43) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 62% (80) | 69% (48) | 54% (32) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 30% (39) | 40% (28) ** | 19% (11) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 29% (37) | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 33% (43) | 30% (21) | 37% (22) | |

| Ask Me 3 (questions for client to ask provider) | 5% (7) | 10% (7) ** | 0% (0) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (51) | 41% (29) | 37% (22) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 13% (17) | 10% (7) | 17% (10) | ||

| Read aloud | 9% (11) | 9% (6) | 8% (5) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (4) | 4% (3) | 2% (1) | ||

| Respond to diversity | |||||

| Cultural awareness | 29% (37) | 26% (18) | 32% (19) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 26% (33) | 26% (18) | 25% (15) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 19% (25) | 10% (7)* | 31% (18) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 5% (6) | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | |||||

| Shared decision making (individual and community) | 19% (24) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Empowerment | 18% (23) | 10% (7)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Trust | 13% (17) | 6% (4)* | 22% (13) | ||

| Respect | 12% (16) | 10% (7) | 15% (9) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 12% (16) | 9% (6) | 17% (10) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 12% (15) | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

aOf the 70 publications from the USA, 66 were USA only and four had authors from the USA and one or more other countries.

Significantly less than those not including USA at *p < 0.05.

Significantly more than those not including USA at **p < 0.05 or ***p ≤ 0.002.

Health literacy responsiveness elements identified in papers organized by themes and sub-themes, and for papers with or without authors from the USA

| All papers (n = 129) . | Countries of authors . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Percentage (number) . | USAa (n = 70) . | Did not include USA (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | |||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 44% (57) | 34% (24) * | 56% (33) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy and/or numeracy | 20% (26) | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 7% (9) | 4% (3) | 10% (6) | ||

| Andragogy | |||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 19% (25) | 27% (19) ** | 10% (6) | |

| Demonstrations | 11% (14) | 10% (7) | 12% (7) | ||

| Underlining key information | 11% (14) | 17% (12) ** | 3% (2) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 58% (75) | 74% (52) *** | 39% (23) | |

| Chunk & Check | 8% (10) | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | |||||

| General | Provide information | 52% (67) | 51% (36) | 53% (31) | |

| Open-ended questions | 18% (23) | 19% (13) | 17% (10) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 74% (96) | 76% (53) | 73% (43) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 62% (80) | 69% (48) | 54% (32) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 30% (39) | 40% (28) ** | 19% (11) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 29% (37) | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 33% (43) | 30% (21) | 37% (22) | |

| Ask Me 3 (questions for client to ask provider) | 5% (7) | 10% (7) ** | 0% (0) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (51) | 41% (29) | 37% (22) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 13% (17) | 10% (7) | 17% (10) | ||

| Read aloud | 9% (11) | 9% (6) | 8% (5) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (4) | 4% (3) | 2% (1) | ||

| Respond to diversity | |||||

| Cultural awareness | 29% (37) | 26% (18) | 32% (19) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 26% (33) | 26% (18) | 25% (15) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 19% (25) | 10% (7)* | 31% (18) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 5% (6) | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | |||||

| Shared decision making (individual and community) | 19% (24) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Empowerment | 18% (23) | 10% (7)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Trust | 13% (17) | 6% (4)* | 22% (13) | ||

| Respect | 12% (16) | 10% (7) | 15% (9) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 12% (16) | 9% (6) | 17% (10) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 12% (15) | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

| All papers (n = 129) . | Countries of authors . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Percentage (number) . | USAa (n = 70) . | Did not include USA (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | |||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 44% (57) | 34% (24) * | 56% (33) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy and/or numeracy | 20% (26) | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 7% (9) | 4% (3) | 10% (6) | ||

| Andragogy | |||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 19% (25) | 27% (19) ** | 10% (6) | |

| Demonstrations | 11% (14) | 10% (7) | 12% (7) | ||

| Underlining key information | 11% (14) | 17% (12) ** | 3% (2) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 58% (75) | 74% (52) *** | 39% (23) | |

| Chunk & Check | 8% (10) | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | |||||

| General | Provide information | 52% (67) | 51% (36) | 53% (31) | |

| Open-ended questions | 18% (23) | 19% (13) | 17% (10) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 74% (96) | 76% (53) | 73% (43) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 62% (80) | 69% (48) | 54% (32) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 30% (39) | 40% (28) ** | 19% (11) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 29% (37) | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 33% (43) | 30% (21) | 37% (22) | |

| Ask Me 3 (questions for client to ask provider) | 5% (7) | 10% (7) ** | 0% (0) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (51) | 41% (29) | 37% (22) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 13% (17) | 10% (7) | 17% (10) | ||

| Read aloud | 9% (11) | 9% (6) | 8% (5) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (4) | 4% (3) | 2% (1) | ||

| Respond to diversity | |||||

| Cultural awareness | 29% (37) | 26% (18) | 32% (19) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 26% (33) | 26% (18) | 25% (15) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 19% (25) | 10% (7)* | 31% (18) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 5% (6) | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | |||||

| Shared decision making (individual and community) | 19% (24) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Empowerment | 18% (23) | 10% (7)* | 27% (16) | ||

| Trust | 13% (17) | 6% (4)* | 22% (13) | ||

| Respect | 12% (16) | 10% (7) | 15% (9) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 12% (16) | 9% (6) | 17% (10) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 12% (15) | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

aOf the 70 publications from the USA, 66 were USA only and four had authors from the USA and one or more other countries.

Significantly less than those not including USA at *p < 0.05.

Significantly more than those not including USA at **p < 0.05 or ***p ≤ 0.002.

Through inductive coding, distinct from these thematic elements, three separate elements were identified: the importance of an inclusive and shame-free environment, tailoring of information and patient-centred care. Tailoring was described as important for catering to individual health literacy strengths and weaknesses, as well as specifically for people with disabilities (Beauchamp et al., 2017; Fallowfield et al., 2019; Komondor and Choudhury, 2021). Patient-centred care as a philosophical approach to health care encompassed a number of the other elements and themes and was considered a way of enacting health literacy responsiveness rather than being an element of it (Coleman et al., 2017; Karuranga et al., 2017; Kaper et al., 2019).

Approximately half of the articles were from the USA, therefore the percentage of articles including particular elements of health literacy responsiveness from the USA were compared to the rest of the data (Table 1). The USA had a considerably greater emphasis on the teach-back technique, and somewhat greater emphasis on limiting the amount of information conveyed at a time, action-oriented instruction, underlining key information and Ask Me 3 questions for the client to ask the provider. The articles included from the USA had less emphasis on assessing clients’ health literacy, consideration of beliefs, empowerment, shared decision making and trust.

Research Q2. What tools exist to measure health professionals’ or health professional students’ health literacy responsiveness?

The review of the 129 included articles identified 54 articles that reported on the use of 44 tools to assess aspects of health literacy responsiveness (Table 2). Thirty of these tools were custom tools (i.e. developed to test the described intervention in that study). As reported by the authors of the articles, the majority (21/30) of these custom tools were not validated for any populations or contexts. Some of the custom tools used survey items from other tools.

| Name of tool . | Validation claim . | Articles . |

|---|---|---|

| Health Literacy Skills Knowledge and Experience (HLSKE) | Yes | Chang, 2020 (modified) |

| Cormier, 2009 | ||

| Dawkins-Moultin, 2019 | ||

| Maduramente, 2019 (with 4 additional items from Knight, 2011) | ||

| Nesari et al., 2019 | ||

| Ogrodnick et al., 2020 (also used CCSTB) | ||

| Torres and Nichols, 2014 | ||

| Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) and Hospital CAPS | Yes | Wilcoxen and King, 2013 |

| Bress et al., 2019 (modifications not validated) | ||

| Health Literacy Assessment Questions | Yes | Tavakoly Sany et al., 2018 |

| Health Literacy Promotion Practices Assessment Instrument (HLPA) | Yes | Squires et al., 2017 |

| Familiarity with Attitudes toward and confidence in implementing health literacy practices | Yes | Chang, 2021 |

| Critical Health Competence Test (CHC Test) | Yes | Hecht (Survey originally developed by Steckelberg et al., 2009) |

| Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) survey | Yes | Ali, 2013 (Survey originally developed by Coleman and Appy, 2010) |

| Patient Education Implementation Scale (PEIS) | Yes | Şenyuva et al., 2020 |

| Custom tools | Yes | Coleman, 2017 |

| Güner and Ekmekci, 2019 | ||

| Koenig, 2019 | ||

| McCleary-Jones, 2012 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2017 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2018 | ||

| Wilcoxen and King, 2013 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2019 | ||

| Muscat et al., 2021 | ||

| Custom tools | No | Allenbaugh, 2019 |

| Bradley, 2015 | ||

| Bress, 2013 | ||

| Cailor, 2015 | ||

| Chen, 2020 | ||

| Coleman, 2015 (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Coleman et al., 2016b (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Dang, 2020 (mental health literacy) | ||

| Goto, 2015 | ||

| Green, 2014 | ||

| Ha, 2014 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2020 (used survey items from Mackert et al., 2011; Coleman & Former, 2015; Coleman et al., 2016a; Coleman et al., 2013; Cafiero, 2013; Trujillo and Figler, 2015 and Kaper, 2018) | ||

| Klingbeil, 2018 | ||

| Kornburger, 2013 | ||

| Lambert, 2014 | ||

| Lori, 2016 | ||

| Mackert, 2011 | ||

| Mnatzaganian, 2017 (modified from Devraj et al., 2010) | ||

| Stone et al., 2021 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2020 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2021 | ||

| Centre of Ethnicity and Health | No | Bird, 2020 |

| AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions toolkit | No | Daus, 2020 |

| Shaikh et al., 2018 | ||

| Trujillo and Figler, 2015 | ||

| Komondor, 2021 | ||

| Weiss et al., 2016 | ||

| Conviction and Confidence Scale for using Teach Back (CCSTB) | No | Holman |

| Ogrodonick (also used HLSKE) | ||

| Health Literacy Practices for Educational Competencies for Health Professionals v2 Europe | No | Karuranga, 2017 |

| Nursing Professional Health Literacy survey | No | Nantsupawat et al., 2020 (Developed by Macabasco-O’Connell and Fry-Bowers, 2011 and translated) |

| Limited Literacy Impact Measure LLIM | No | Jukkala, 2009 |

| Name of tool . | Validation claim . | Articles . |

|---|---|---|

| Health Literacy Skills Knowledge and Experience (HLSKE) | Yes | Chang, 2020 (modified) |

| Cormier, 2009 | ||

| Dawkins-Moultin, 2019 | ||

| Maduramente, 2019 (with 4 additional items from Knight, 2011) | ||

| Nesari et al., 2019 | ||

| Ogrodnick et al., 2020 (also used CCSTB) | ||

| Torres and Nichols, 2014 | ||

| Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) and Hospital CAPS | Yes | Wilcoxen and King, 2013 |

| Bress et al., 2019 (modifications not validated) | ||

| Health Literacy Assessment Questions | Yes | Tavakoly Sany et al., 2018 |

| Health Literacy Promotion Practices Assessment Instrument (HLPA) | Yes | Squires et al., 2017 |

| Familiarity with Attitudes toward and confidence in implementing health literacy practices | Yes | Chang, 2021 |

| Critical Health Competence Test (CHC Test) | Yes | Hecht (Survey originally developed by Steckelberg et al., 2009) |

| Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) survey | Yes | Ali, 2013 (Survey originally developed by Coleman and Appy, 2010) |

| Patient Education Implementation Scale (PEIS) | Yes | Şenyuva et al., 2020 |

| Custom tools | Yes | Coleman, 2017 |

| Güner and Ekmekci, 2019 | ||

| Koenig, 2019 | ||

| McCleary-Jones, 2012 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2017 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2018 | ||

| Wilcoxen and King, 2013 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2019 | ||

| Muscat et al., 2021 | ||

| Custom tools | No | Allenbaugh, 2019 |

| Bradley, 2015 | ||

| Bress, 2013 | ||

| Cailor, 2015 | ||

| Chen, 2020 | ||

| Coleman, 2015 (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Coleman et al., 2016b (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Dang, 2020 (mental health literacy) | ||

| Goto, 2015 | ||

| Green, 2014 | ||

| Ha, 2014 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2020 (used survey items from Mackert et al., 2011; Coleman & Former, 2015; Coleman et al., 2016a; Coleman et al., 2013; Cafiero, 2013; Trujillo and Figler, 2015 and Kaper, 2018) | ||

| Klingbeil, 2018 | ||

| Kornburger, 2013 | ||

| Lambert, 2014 | ||

| Lori, 2016 | ||

| Mackert, 2011 | ||

| Mnatzaganian, 2017 (modified from Devraj et al., 2010) | ||

| Stone et al., 2021 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2020 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2021 | ||

| Centre of Ethnicity and Health | No | Bird, 2020 |

| AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions toolkit | No | Daus, 2020 |

| Shaikh et al., 2018 | ||

| Trujillo and Figler, 2015 | ||

| Komondor, 2021 | ||

| Weiss et al., 2016 | ||

| Conviction and Confidence Scale for using Teach Back (CCSTB) | No | Holman |

| Ogrodonick (also used HLSKE) | ||

| Health Literacy Practices for Educational Competencies for Health Professionals v2 Europe | No | Karuranga, 2017 |

| Nursing Professional Health Literacy survey | No | Nantsupawat et al., 2020 (Developed by Macabasco-O’Connell and Fry-Bowers, 2011 and translated) |

| Limited Literacy Impact Measure LLIM | No | Jukkala, 2009 |

| Name of tool . | Validation claim . | Articles . |

|---|---|---|

| Health Literacy Skills Knowledge and Experience (HLSKE) | Yes | Chang, 2020 (modified) |

| Cormier, 2009 | ||

| Dawkins-Moultin, 2019 | ||

| Maduramente, 2019 (with 4 additional items from Knight, 2011) | ||

| Nesari et al., 2019 | ||

| Ogrodnick et al., 2020 (also used CCSTB) | ||

| Torres and Nichols, 2014 | ||

| Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) and Hospital CAPS | Yes | Wilcoxen and King, 2013 |

| Bress et al., 2019 (modifications not validated) | ||

| Health Literacy Assessment Questions | Yes | Tavakoly Sany et al., 2018 |

| Health Literacy Promotion Practices Assessment Instrument (HLPA) | Yes | Squires et al., 2017 |

| Familiarity with Attitudes toward and confidence in implementing health literacy practices | Yes | Chang, 2021 |

| Critical Health Competence Test (CHC Test) | Yes | Hecht (Survey originally developed by Steckelberg et al., 2009) |

| Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) survey | Yes | Ali, 2013 (Survey originally developed by Coleman and Appy, 2010) |

| Patient Education Implementation Scale (PEIS) | Yes | Şenyuva et al., 2020 |

| Custom tools | Yes | Coleman, 2017 |

| Güner and Ekmekci, 2019 | ||

| Koenig, 2019 | ||

| McCleary-Jones, 2012 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2017 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2018 | ||

| Wilcoxen and King, 2013 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2019 | ||

| Muscat et al., 2021 | ||

| Custom tools | No | Allenbaugh, 2019 |

| Bradley, 2015 | ||

| Bress, 2013 | ||

| Cailor, 2015 | ||

| Chen, 2020 | ||

| Coleman, 2015 (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Coleman et al., 2016b (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Dang, 2020 (mental health literacy) | ||

| Goto, 2015 | ||

| Green, 2014 | ||

| Ha, 2014 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2020 (used survey items from Mackert et al., 2011; Coleman & Former, 2015; Coleman et al., 2016a; Coleman et al., 2013; Cafiero, 2013; Trujillo and Figler, 2015 and Kaper, 2018) | ||

| Klingbeil, 2018 | ||

| Kornburger, 2013 | ||

| Lambert, 2014 | ||

| Lori, 2016 | ||

| Mackert, 2011 | ||

| Mnatzaganian, 2017 (modified from Devraj et al., 2010) | ||

| Stone et al., 2021 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2020 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2021 | ||

| Centre of Ethnicity and Health | No | Bird, 2020 |

| AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions toolkit | No | Daus, 2020 |

| Shaikh et al., 2018 | ||

| Trujillo and Figler, 2015 | ||

| Komondor, 2021 | ||

| Weiss et al., 2016 | ||

| Conviction and Confidence Scale for using Teach Back (CCSTB) | No | Holman |

| Ogrodonick (also used HLSKE) | ||

| Health Literacy Practices for Educational Competencies for Health Professionals v2 Europe | No | Karuranga, 2017 |

| Nursing Professional Health Literacy survey | No | Nantsupawat et al., 2020 (Developed by Macabasco-O’Connell and Fry-Bowers, 2011 and translated) |

| Limited Literacy Impact Measure LLIM | No | Jukkala, 2009 |

| Name of tool . | Validation claim . | Articles . |

|---|---|---|

| Health Literacy Skills Knowledge and Experience (HLSKE) | Yes | Chang, 2020 (modified) |

| Cormier, 2009 | ||

| Dawkins-Moultin, 2019 | ||

| Maduramente, 2019 (with 4 additional items from Knight, 2011) | ||

| Nesari et al., 2019 | ||

| Ogrodnick et al., 2020 (also used CCSTB) | ||

| Torres and Nichols, 2014 | ||

| Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) and Hospital CAPS | Yes | Wilcoxen and King, 2013 |

| Bress et al., 2019 (modifications not validated) | ||

| Health Literacy Assessment Questions | Yes | Tavakoly Sany et al., 2018 |

| Health Literacy Promotion Practices Assessment Instrument (HLPA) | Yes | Squires et al., 2017 |

| Familiarity with Attitudes toward and confidence in implementing health literacy practices | Yes | Chang, 2021 |

| Critical Health Competence Test (CHC Test) | Yes | Hecht (Survey originally developed by Steckelberg et al., 2009) |

| Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) survey | Yes | Ali, 2013 (Survey originally developed by Coleman and Appy, 2010) |

| Patient Education Implementation Scale (PEIS) | Yes | Şenyuva et al., 2020 |

| Custom tools | Yes | Coleman, 2017 |

| Güner and Ekmekci, 2019 | ||

| Koenig, 2019 | ||

| McCleary-Jones, 2012 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2017 | ||

| Rajah et al., 2018 | ||

| Wilcoxen and King, 2013 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2019 | ||

| Muscat et al., 2021 | ||

| Custom tools | No | Allenbaugh, 2019 |

| Bradley, 2015 | ||

| Bress, 2013 | ||

| Cailor, 2015 | ||

| Chen, 2020 | ||

| Coleman, 2015 (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Coleman et al., 2016b (survey developed by Mackert at al., 2011) | ||

| Dang, 2020 (mental health literacy) | ||

| Goto, 2015 | ||

| Green, 2014 | ||

| Ha, 2014 | ||

| Kaper et al., 2020 (used survey items from Mackert et al., 2011; Coleman & Former, 2015; Coleman et al., 2016a; Coleman et al., 2013; Cafiero, 2013; Trujillo and Figler, 2015 and Kaper, 2018) | ||

| Klingbeil, 2018 | ||

| Kornburger, 2013 | ||

| Lambert, 2014 | ||

| Lori, 2016 | ||

| Mackert, 2011 | ||

| Mnatzaganian, 2017 (modified from Devraj et al., 2010) | ||

| Stone et al., 2021 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2020 | ||

| van der Giessen et al., 2021 | ||

| Centre of Ethnicity and Health | No | Bird, 2020 |

| AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions toolkit | No | Daus, 2020 |

| Shaikh et al., 2018 | ||

| Trujillo and Figler, 2015 | ||

| Komondor, 2021 | ||

| Weiss et al., 2016 | ||

| Conviction and Confidence Scale for using Teach Back (CCSTB) | No | Holman |

| Ogrodonick (also used HLSKE) | ||

| Health Literacy Practices for Educational Competencies for Health Professionals v2 Europe | No | Karuranga, 2017 |

| Nursing Professional Health Literacy survey | No | Nantsupawat et al., 2020 (Developed by Macabasco-O’Connell and Fry-Bowers, 2011 and translated) |

| Limited Literacy Impact Measure LLIM | No | Jukkala, 2009 |

Fourteen tools to assess some general aspects of health literacy responsiveness were identified. The ‘Health Literacy Skills, Knowledge and Experience’ (HLSKE) was the most frequently used tool, reported in seven studies. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ARHQ) Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit from the USA was used in five studies. Of the pre-existing tools reported, eight of these reports mentioned prior validation or provided evidence of validation of the instrument in one or more populations.

Research Q3. What important measurable elements and attributes are included in the education and training of health professionals or health professional students to ensure they are responsive to their healthcare users’ health literacy?

Seventy articles reviewed had an education or training element. The proportion of studies reporting education or training did not differ between the USA (n = 42 of 70, 60%) and the rest of the world (n = 28 of 59, 47%) by Chi-squared test (p = 0.15). The majority of this education was delivered to health professionals as professional development activities (n = 45, 64%). Some included both students and health professionals (n = 5, 7%) or students only (n = 20, 29%). The authors of the articles reported that the training was delivered face-to-face (n = 62, 89%), online (n = 5, 7%) or blended (n = 3, 4%). Nearly identical numbers of training programmes were <2 hours (n = 22, 31%), 2–4 hours (n = 22, 31%) or >4 hours (n = 23, 33%) in duration, delivered as one-off educational events (n = 28, 40%) or multiple sessions (n = 39, 56%), with a small number of manuscripts not providing this information (n = 2, 3%) or describing multiple educational approaches (n = 1, 1%). Training or education was classified as didactic (e.g. lectures, n = 13, 19%), interactive (n = 52, 74%) or both (n = 5, 7%). Evaluation of training included trainee attitudes or self-reported confidence (n = 22, 31%), objective measures of learning or behaviour (n = 28, 40%) or impacts on patient outcomes (n = 16, 23%); a small number of manuscripts did not report any evaluation (n = 4, 6%).

The articles including education were analysed to determine the frequency of health literacy responsiveness elements. Articles reporting training differed from those that did not describe training in several areas of health literacy responsiveness, with significantly less emphasis on technology or multimedia options, reading aloud and trust, and somewhat less emphasis on digital literacy, encouraging clients to ask questions, shared decision making, respect and establishing existing social supports (Table 3).

Percentages and counts of papers with health literacy responsiveness elements, by whether or not training or education was provided, organized by themes and sub-themes

| Training or education provided . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Yes (n = 70) . | No (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | ||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 39% (27) | 51% (30) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy (reading/writing) and/or numeracy | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 1% (1)* | 14% (8) | ||

| Andragogy | ||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 17% (12) | 22% (13) | |

| Demonstrations | 7% (5) | 15% (9) | ||

| Underlining key information | 9% (6) | 14% (8) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 66% (46) | 49% (29) | |

| Chunk & Check | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | ||||

| General | Provide information | 47% (33) | 58% (34) | |

| Open-ended questions | 20% (14) | 15% (9) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 79% (55) | 69% (41) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 66% (46) | 58% (34) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 29% (20) | 32% (19) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 30% (21) | 27% (16) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 24% (17)* | 44% (26) | |

| Ask Me 3 (client to ask provider) | 7% (5) | 3% (2) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (28) | 39% (23) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Read aloud | 1% (1)** | 17% (10) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (2) | 3% (2) | ||

| Respond to diversity | ||||

| Cultural awareness | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 20% (14) | 32% (19) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 14% (10) | 25% (15) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | Shared decision making (individual and community) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | |

| Empowerment | 13% (9) | 24% (14) | ||

| Trust | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Respect | 7% (5)* | 19% (11) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 6% (4)* | 20% (12) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

| Training or education provided . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Yes (n = 70) . | No (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | ||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 39% (27) | 51% (30) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy (reading/writing) and/or numeracy | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 1% (1)* | 14% (8) | ||

| Andragogy | ||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 17% (12) | 22% (13) | |

| Demonstrations | 7% (5) | 15% (9) | ||

| Underlining key information | 9% (6) | 14% (8) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 66% (46) | 49% (29) | |

| Chunk & Check | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | ||||

| General | Provide information | 47% (33) | 58% (34) | |

| Open-ended questions | 20% (14) | 15% (9) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 79% (55) | 69% (41) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 66% (46) | 58% (34) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 29% (20) | 32% (19) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 30% (21) | 27% (16) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 24% (17)* | 44% (26) | |

| Ask Me 3 (client to ask provider) | 7% (5) | 3% (2) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (28) | 39% (23) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Read aloud | 1% (1)** | 17% (10) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (2) | 3% (2) | ||

| Respond to diversity | ||||

| Cultural awareness | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 20% (14) | 32% (19) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 14% (10) | 25% (15) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | Shared decision making (individual and community) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | |

| Empowerment | 13% (9) | 24% (14) | ||

| Trust | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Respect | 7% (5)* | 19% (11) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 6% (4)* | 20% (12) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

Significantly less than those not including health literacy responsiveness education at

*p < 0.05 or

**p ≤ 0.002.

Percentages and counts of papers with health literacy responsiveness elements, by whether or not training or education was provided, organized by themes and sub-themes

| Training or education provided . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Yes (n = 70) . | No (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | ||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 39% (27) | 51% (30) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy (reading/writing) and/or numeracy | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 1% (1)* | 14% (8) | ||

| Andragogy | ||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 17% (12) | 22% (13) | |

| Demonstrations | 7% (5) | 15% (9) | ||

| Underlining key information | 9% (6) | 14% (8) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 66% (46) | 49% (29) | |

| Chunk & Check | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | ||||

| General | Provide information | 47% (33) | 58% (34) | |

| Open-ended questions | 20% (14) | 15% (9) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 79% (55) | 69% (41) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 66% (46) | 58% (34) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 29% (20) | 32% (19) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 30% (21) | 27% (16) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 24% (17)* | 44% (26) | |

| Ask Me 3 (client to ask provider) | 7% (5) | 3% (2) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (28) | 39% (23) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Read aloud | 1% (1)** | 17% (10) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (2) | 3% (2) | ||

| Respond to diversity | ||||

| Cultural awareness | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 20% (14) | 32% (19) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 14% (10) | 25% (15) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | Shared decision making (individual and community) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | |

| Empowerment | 13% (9) | 24% (14) | ||

| Trust | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Respect | 7% (5)* | 19% (11) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 6% (4)* | 20% (12) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

| Training or education provided . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme . | Subtheme . | Health literacy responsiveness measurable elements . | Yes (n = 70) . | No (n = 59) . |

| Literacies | ||||

| Assess patient’s health literacy | 39% (27) | 51% (30) | ||

| Assess patient’s general literacy (reading/writing) and/or numeracy | 16% (11) | 25% (15) | ||

| Digital literacy / e-health | 1% (1)* | 14% (8) | ||

| Andragogy | ||||

| Teaching | Action-oriented instruction | 17% (12) | 22% (13) | |

| Demonstrations | 7% (5) | 15% (9) | ||

| Underlining key information | 9% (6) | 14% (8) | ||

| Check for understanding | Teach-Back Technique | 66% (46) | 49% (29) | |

| Chunk & Check | 10% (7) | 5% (3) | ||

| Communication | ||||

| General | Provide information | 47% (33) | 58% (34) | |

| Open-ended questions | 20% (14) | 15% (9) | ||

| Plain | Communicate clearly | 79% (55) | 69% (41) | |

| Avoid jargon / use plain language | 66% (46) | 58% (34) | ||

| Limit information (2–3 concepts at a time) | 29% (20) | 32% (19) | ||

| Universal precautions (assume all have low HL) | 30% (21) | 27% (16) | ||

| Bidirectional | Encourage client to ask questions | 24% (17)* | 44% (26) | |

| Ask Me 3 (client to ask provider) | 7% (5) | 3% (2) | ||

| Multimodal | Use images, diagrams or models | 40% (28) | 39% (23) | |

| Technology, multimedia | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Read aloud | 1% (1)** | 17% (10) | ||

| More white space in written information | 3% (2) | 3% (2) | ||

| Respond to diversity | ||||

| Cultural awareness | 27% (19) | 31% (18) | ||

| Adapt for CALD (e.g. translator services, family) | 20% (14) | 32% (19) | ||

| Consider personal and health beliefs | 14% (10) | 25% (15) | ||

| Avoid stigmatizing language and images | 3% (2) | 7% (4) | ||

| Social / relational | Shared decision making (individual and community) | 11% (8)* | 27% (16) | |

| Empowerment | 13% (9) | 24% (14) | ||

| Trust | 4% (3)** | 24% (14) | ||

| Respect | 7% (5)* | 19% (11) | ||

| Establish existing social supports | 6% (4)* | 20% (12) | ||

| Influence of socioeconomic factors on health | 11% (8) | 12% (7) | ||

Significantly less than those not including health literacy responsiveness education at

*p < 0.05 or

**p ≤ 0.002.

DISCUSSION

This review was undertaken to identify measurable elements and attributes of the health literacy responsiveness of health professionals, health workers or students of health disciplines, tools that currently exist to measure these and education and training provided related to them. Regional differences between the USA and other countries were identified, highlighting that international contexts and socio-cultural markers need to be considered in the provision of education and the development of any tool that aims to measure these elements. Studies from the USA studies focused heavily on the teach-back technique; however, there was less emphasis on assessing health literacy and adapting for diversity through empowering healthcare users. In summary, assessing health literacy, adult-focused teaching methods, plain, bidirectional and multimodal communication, adaptations for diverse populations and socio-relational strategies are required to enact health literacy responsiveness. A recommendation from this review is that an interpretive guide, including the key elements, their definitions and a series of examples of these elements in practice could be developed to enable health professionals to enact health literacy responsiveness in an appropriate and comprehensive manner relevant to their context.

Our review shows that while there are regional differences in the context and interpretation of health literacy responsiveness, which may limit the generalizability of any one tool to be used universally, there are several related elements that are frequently reported and have broad applicability. First, plain, clear communication is the most common strategy adopting plain language and avoiding jargon. Second, bidirectional communication approaches such as checking for understanding (teach-back), encouraging healthcare users to ask questions and using open-ended questions are also common. Third, in providing information, limiting to a few concepts at a time and taking a universal precautions approach are regularly implemented. Fourth, somewhat conversely, assessing clients’ health and/or general literacy was frequently implemented. Fifth, the use of images, diagrams, models or multimedia to support communication were collectively used often. Sixth, awareness of and adaptation for cultural and linguistic diversity, such as the use of translator services, were not uncommon. Seventh, empowering clients through considering their beliefs and encouraging shared decision making were in a significant minority of studies. These findings may inform the future development of a tool to assess the health literacy responsiveness of health professionals which combines the findings from the literature to inform a grounded approach for development. (Coleman et al., 2013; Osborne et al., 2013; Trezona et al., 2017; Kayser et al., 2018).

This review identified tools that were predominantly developed in response to a particular educational or training intervention and tailor-made for this specific purpose. In Haun et al. conducted an inventory of health literacy tools and found most of the 51 tools located were developed with a specific context in mind, making it challenging to use across contexts and impossible to compare results (Haun et al., 2014). In contrast, this scoping review located measured aspects of health literacy responsiveness that were expected outcomes of education or training. A recent scoping review (Cesar et al., 2022) examined 34 articles to classify and map the characteristics and interventions that make health care professionals responsive to patients’ health literacy. They deductively coded their findings into the knowledge, skills and attributes framework and provided insight into the various strategies that health professionals may employ in the delivery of education to patients. While we have also focused on identifying how health professionals can respond to health literacy needs, we have also provided a count of elements and attributes in conjunction with information about how health professionals and students can be trained to develop health literacy responsiveness, thus adding new insights to the international literature.

Of the 30 custom tools that were tailor-made, only nine of them had undergone any form of validation, which may indicate an intention to use these tools either only once or for a very specific purpose. This finding limits the generalizability of these custom tools in other studies. In addition to these custom tools, 14 tools were identified that measured aspects of health literacy responsiveness across a broader range of contexts. The HLSKE and the ARHQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit were the most frequently used. Both of these tools were developed prior to the publication of key health literacy guidance from the WHO and therefore may not be informed by more contemporary health literacy definitions and elements and attributes of health literacy responsiveness (Nutbeam and Muscat, 2021; WHO, 2022).

Across the reviewed articles and those that describe educational approaches, the minority of research regarding health literacy responsiveness was conducted with entry-to-practice health professionals, suggesting that health literacy responsiveness has seldom been included and measured in entry-to-practice curricula. This may be driving continual professional development events to develop these skills in practice. A systematic review of health literacy training in health professional education found a similarly rather small number (n = 28) of studies (Saunders et al., 2019). The list of elements describing health literacy responsiveness generated from the present review, combined with other reviews (Coleman, 2011; Saunders et al., 2019) and compilations of competencies [e.g. (Coleman et al., 2013)] may support health professional educators globally to include these in curricula and evaluate the learning and teaching that is delivered.

While there are a considerable number of health literacy responsiveness tools in existence (Table 2), the future development of a validated tool to assess health literacy responsiveness, based on the findings from this review and more contemporary definitions of health literacy [e.g. (Nutbeam and Lloyd, 2021)] may support more health professionals and students to become health literacy responsive in their practice. In recognition of the contextual and cultural nature of health literacy, it will be important that researchers involved in tool development use appropriate strategies including co-design workshops with key stakeholders to ensure the tool reflects the health literacy responsive attributes most appropriate to the local country, context and cultures (Sørensen and Brand, 2014; WHO, 2022). It may not be possible to develop a generic health literacy responsive health professionals’ tool that can be utilized across all countries globally; however, the set of attributes outlined in this review could provide the foundation for each nation to conduct research to develop their own tool. Whilst it is important to acknowledge these differences, it may be that over time, core attributes can be identified that stakeholders in all nations will recognize as important to becoming or being a health literacy-responsive health professional (WHO, 2022).

Limitations and strengths

This scoping review did not include grey literature or include papers written and published in languages other than English and limits generalizability of this data to countries that do not use English as a predominant language. Given most of the tools were developed for specific interventions, are not validated and are representative of many regions internationally, their generalizability may be limited. The search was robust, and the data thoroughly analysed to produce a detailed description of health literacy-responsive elements in the current literature. The review commenced with a pilot search to refine the search strategy, it used Covidence software and had two independent researchers review each paper against a pre-determined inclusion criteria. The extraction process was thorough and also involved two researchers for each paper to ensure the accuracy of the data tabulated. In both stages (review and extraction), a third researcher was involved to support the consensus process.

CONCLUSION

This review provides a comprehensive and contemporary description of the elements and attributes required to be a health literacy-responsive health professional. This review collated and documented the existing tools and education programmes available for health professionals and individuals studying to become health professionals. There are multiple potential uses for these findings, including providing the foundation (elements and attributes) to inform the development of tool(s) to comprehensively measure a health professional’s health literacy responsiveness in a range of health systems, countries and cultures. The findings could inform the development of curricula guides to support health disciplines in both the undergraduate and graduate professional development arenas to ensure their graduates are health literacy responsive in their practice. Given the important role health literacy plays in population health outcomes, policy, practice and educational research must support the development of health literacy-responsive health professionals into the future.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors confirm that they have contributed to the conception and design of the project, analysis or interpretation of the research data and drafting or critically revising the manuscript. All authors have approved the final copy of this manuscript.

FUNDING

No external funding was received for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest for this project.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was not required for this scoping review.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.