-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Eibhlin Higgins, Ji Yuan, Sawyer Lange, Barry A Boilson, Bobbi S Pritt, Stacey A Rizza, Fever, Cough, and Pancytopenia in a Transplant Recipient, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 77, Issue 7, 1 October 2023, Pages 1065–1067, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad167

Close - Share Icon Share

A 19-year-old male presented with fevers, chills, malaise, generalized aches, and a nonproductive cough. Twelve months prior to presentation, he underwent orthotopic heart and renal transplantation and was immunosuppressed with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. Two weeks prior to presentation, a routine echocardiogram demonstrated global hypokinesis and a reduced ejection fraction of 28%. A cardiac biopsy showed evidence of acute cell-mediated rejection, and he was treated with pulsed methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, and rituximab.

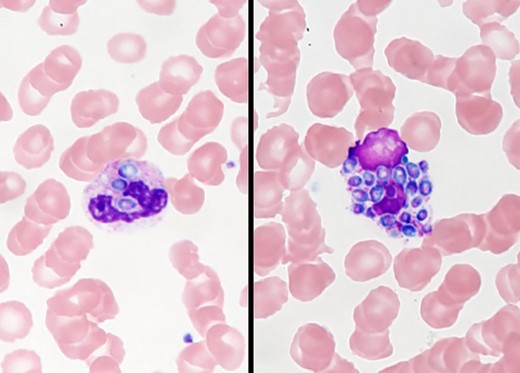

On examination, he appeared acutely unwell, was febrile to 39.1 °C, and was hypoxemic with an oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. Heart rate and blood pressure were within normal ranges. Abnormal physical exam findings included scleral icterus, elevated jugular venous pressure, and reduced breath sounds at the lung bases. Laboratory workup was notable for leukopenia with a total white cell count of 1.8 × 109/L (neutrophils, 1.22 × 109/L; lymphocytes, 0.09 × 109/L), thrombocytopenia with platelet count 56 × 109/L, acute kidney injury with blood urea nitrogen 110 mg/dL and creatinine 5.5 mg/dL, as well as a deranged liver profile with total bilirubin 6.4 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 1043 units/L, alanine aminotransferase 40 units/L, and aspartate aminotransferase 224 units/L. Ferritin was markedly elevated at 43 625 µg/L. Computed tomography of the chest demonstrated tree-in-bud nodular changes bilaterally, most prominent in the left lower zone. He was empirically started on intravenous (IV) cefepime, vancomycin, and oral doxycycline. A peripheral blood smear was done for evaluation of cytopenia and is shown in Figure 1.

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Disseminated histoplasmosis.

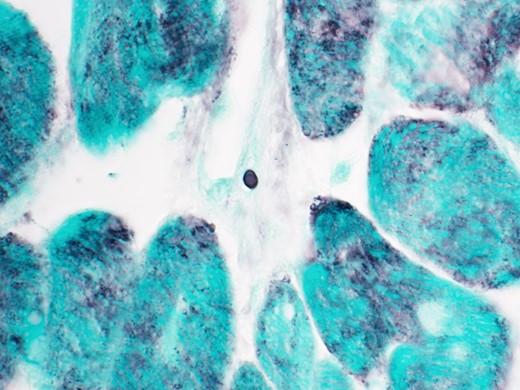

The most notable finding on the peripheral blood smear is the presence of phagocytic vacuoles filled with oval-shaped organisms within the leukocyte. Urine Histoplasma antigen was detected at >25 ng/mL. Histoplasma antibodies were positive with titers of 1:8 (mycelial) and 1:64 (yeast). Blood cultures subsequently grew Histoplasma species complex. The patient was switched to IV liposomal amphotericin B and oral itraconazole with rapid clinical improvement. A repeat cardiac biopsy demonstrated occasional Gomori methenamine silver (GMS)–positive organisms (Figure 2) suggestive of cardiac histoplasmosis. His ferritin on day 4 of antifungal therapy had declined to 6470 µg/L. He was discharged in stable condition on hospital day 10 and was doing well at his 1-month outpatient follow-up.

GMS stain of cardiac biopsy showing rare small oval yeast consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum (100× magnification).

Histoplasma capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus, classically described as highly endemic to the Mississippi River and Ohio River Valley regions, although recent data demonstrate incident cases in geographic areas far beyond these regions [1, 2]. Infection in immunocompetent hosts may be asymptomatic. Infection in solid organ transplant recipients is often disseminated, as in this case, and may include pulmonary, liver, splenic, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system involvement [3]. Adrenal involvement and resultant insufficiency can lead to presentation with shock. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is well described in association with histoplasmosis, particularly in persons living with human immunodeficiency virus [4]. Although this patient did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for HLH, the ferritin level of >40 000 µg/L at presentation was suggestive of a secondary HLH syndrome [5].

Histoplasmosis in solid organ transplant recipients is relatively rare, with a 12-month cumulative incidence rate of. 102% reported in the 5-year multicenter Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network Study, with the majority of infections occurring within the first 2 years post-transplantation [6]. Infection may be donor-derived, related to reactivation, or primary infection related to post-transplant exposure. Screening for histoplasmosis prior to transplantation is not routinely recommended, although patients who have had histoplasmosis in the 2 years prior to transplantation may be considered for prophylaxis [7]. With fungemia and high infection burden, as in this case, diagnosis can be made through direct visualization of yeast or culture of the organism. In general, diagnosis relies on serologic or antigen-based testing. The immunosuppression associated with solid organ transplantation limits the sensitivity of serologic testing in this group, but Histoplasma antigen assays are rapid, noninvasive, and widely available. Histoplasma may also be detected in clinical samples via targeted polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or with broad-range PCR of fungal 28S ribosome. Liposomal amphotericin and itraconazole are first-line agents for the treatment of histoplasmosis. For severe disease, induction therapy with liposomal amphotericin is recommended for 1–2 weeks followed by step-down therapy with itraconazole [7]. Itraconazole has been associated with cardiac toxicity in the form of new or worsening congestive heart failure, a side effect particularly deleterious for a heart transplant recipient [8]. A previous single-center case series of 31 patients with itraconazole toxicity demonstrated a median age of 66 years and a mean total itraconazole level of 5.2 µg/mL in the cases [9]. In retrospective data, the use of voriconazole as alternate step-down therapy has been associated with increased mortality [10]. Thus, we elected to use itraconazole with close therapeutic drug monitoring. An echocardiogram at the 1-month follow-up showed improvement in ejection fraction, reflecting clinical response to therapy. Management of severe, disseminated infection in the immunocompromised host requires a concomitant reduction in immunosuppression. Histoplasma is a rare but important cause of morbidity and mortality post solid organ transplantation. Recognition of the associated clinical syndrome and prompt initiation of antifungal therapy are crucial in improving outcomes.

Notes

Informed consent statement. Case details have been anonymized, and the patient signed a consent form permitting publication of this case and clinical images.

References

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. B. S. P. reports textbook royalties, a board of governors role, and meeting travel support (CAP Residents Forum) from the College of American Pathologists and meeting travel support from the American Society for Microbiology and the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.