-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Carlos Ramiro Silva-Ramos, Abraham Katime Zúñiga, Edinson E Castillo-Lobo, Jesús A Cortés-Vecino, Álvaro A Faccini-Martínez, Orbital Cavity Infestation, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 77, Issue 7, 1 October 2023, Pages 1068–1071, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad157

Close - Share Icon Share

A 63-year-old male with mental illness and a history of bilateral intraocular lens implantation was found on the street by the local police and taken to the emergency department. The man had severe left ocular pain with associated edema and foul-smelling purulent discharge. Maggots were present within the orbital cavity.

On initial examination, the left orbit was enlarged with marked bi-palpebral edema, periorbital tissues were swollen and erythematous, and a fetid purulent discharge was emanating from the orbit with several live larvae within the eye socket (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the hospital. Routine laboratory tests demonstrated a decreased number of erythrocytes and reduced hemoglobin and hematocrit. Elevated C-reactive protein and serum glucose were also noted. Antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone and clindamycin was initiated.

Enlarged left orbit with bi-palpebral edema, swollen and erythematous periorbital tissues, and live larvae coming out of the eye socket (arrow).

After evaluation by the infectious diseases service, ceftriaxone and clindamycin were discontinued, and ivermectin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and vancomycin were initiated. Cultures of the blood and ocular discharge were negative. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis, and syphilis were nonreactive. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated partial destruction of the left eyeball with an associated inflammatory–infective process of the superficial soft tissues and the medial rectus muscle. These findings prompted evaluation by the ophthalmology service.

Surgical exploration of the affected orbit was performed. A penetrating lesion at the internal angle of the upper left eyelid was seen; irrigation and debridement were performed. The eyeball was subsequently examined, and a necrotic ulcerative lesion of the cornea (comprising approximately 80% of its total surface) was noted, necessitating complete enucleation of the left eyeball. The wound was left open for continued cleaning until complete healing could be achieved (Figure 2). Initially, a gentamicin-soaked gauze bandage was left in the orbit for 24 hours, then replaced with a nitrofurazone gauze bandage. During this process, 72 living larvae were extracted from the orbit. Representative specimens were collected and preserved in 70% ethanol for identification (Figure 3).

Complete enucleation of the left eyeball. The surgical wound was left open for cleaning.

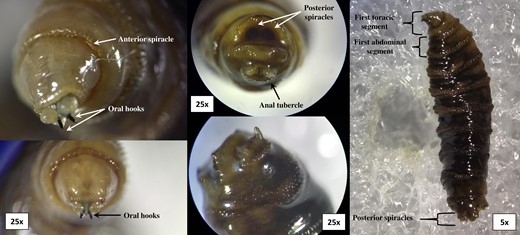

Images of Cochliomyia hominivorax L3 larvae taken with an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope in which the anterior spiracle, oral hooks, posterior spiracles, and anal tubercle can be seen.

Diagnosis: Orbital myiasis caused by Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858).

Myiasis is a term used to describe a disease caused by several larval species of true flies of the order Diptera that can affect several mammalian hosts, including humans [1]. Dipterous larvae can feed on living or dead host tissues, as well as several body fluids, causing a broad range of clinical manifestations depending on the anatomic location and the host’s immune status [1]. This disease mainly occurs in poor regions of tropical and subtropical areas and can be classified according to the anatomical site that is affected [1, 2]. Identification of larvae is critical to elucidating the mechanism of acquisition, initiating appropriate treatment, and implementing measures to prevent additional cases [3]. Despite its occurrence in several regions worldwide, myiasis is still considered a stigmatizing disease, as it is associated with low socioeconomic status and suboptimal sanitary conditions, which are considered the main risk factors [4].

Several dipterous fly species are associated with specific clinical presentations of the disease [1]. One of them, Cochliomyia hominivorax, a fly distributed in tropical and warm temperate regions of Caribbean and South American countries, causes wound myiasis, which is typically a very painful form of the disease. Cochliomyia hominivorax larvae are true obligate parasites of mammals; the adult form lays a large number of eggs on wounds or surrounding areas in only a few minutes [5]. In humans, C. hominivorax infestation most often occurs when an open wound preexists in a person with poor hygiene. The clinical presentation is often severe with penetration and destruction of underlying tissues [1, 6]. Elderly patients with a lack of access to medical care, psychiatric comorbidities, and alcohol dependence and unhoused populations are at increased risk for wound myiasis. When cavitary lesions are formed, the presence of larvae produces a foul-smelling bloody or purulent discharge. This makes it difficult to extract the larvae and can lead to clinical worsening [1, 6]. Diagnosis of wound myiasis is usually clinical. There should be a high degree of suspicion when pain and sensation of movement within tissues are accompanied by a malodorous suppurating sore. Treatment includes removal of larvae, debridement of necrotic tissue, and irrigation of cavities. Topical treatment with ivermectin may also be beneficial [1].

Cavitary myiasis is a form of the disease in which larval infestation occurs in natural body cavities; the infestation receives the name of the anatomic region affected [7]. One form of cavitary myiasis is ophthalmomyiasis or oculomyiasis, which can be classified in ophthalmomyiasis externa, ophthalmomyiasis interna, and orbital myiasis, or “ophtalmomyiase profonde” [1]. Orbital myiasis is one of the most severe forms of the disease. It results as a complication of eyelid wound myiasis in which intraocular invasion of larvae occurs. Thus, the causative agents of orbital myiasis are the same as for wound myiasis [8]. Destruction of the eyeball and the orbit can occur with progressive inflammation to surrounding structures. Management includes topical steroids, surgical removal of viable larvae, and enucleation and exenteration of the eyeball to prevent intracranial extension when damage is extensive. Ivermectin can be used to prevent extension of the necrotizing process into deeper structures and to decrease the risk of lethal outcomes [8, 9]. In summary, orbital myiasis progresses rapidly and can destroy orbital tissues, especially in patients with suboptimal sanitary conditions. Treatment consists of removal of the larvae, surgical debridement, and proper wound care.

Notes

Author Contributions. A. K. Z. and E. C. L. provided the patient's medical care. J. A. C. V. provided the Cochliomyia hominivorax L3 taxonomic study. C. R. S. R. and Á. A. F. M. conceived the manuscript. C. R. S. R. wrote the draft manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for relevant intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Dr Lucas S. Blanton for proofreading, editing, and providing constructive review of the manuscript.

Ethics statement. No individually identifiable patient information has been revealed in this article. The study procedure was done in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The patient's consent was obtained through the Free and Informed Consent Form.

References

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.