-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anna Amela Valsecchi, Simona Pisegna, Andrea Antonuzzo, Grazia Arpino, Giampaolo Bianchini, Laura Biganzoli, Giuseppe Ferdinando Colloca, Carmen Criscitiello, Romano Danesi, Alessandra Fabi, Raffaele Giusti, Loredana Pau, Massimo Di Maio, Daniele Santini, Delphi consensus on the management of adverse events in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer treated with sacituzumab govitecan, The Oncologist, Volume 30, Issue 5, May 2025, oyaf088, https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyaf088

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background

Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (BC; mTNBC) is one of the most aggressive cancers, difficult to treat due to the absence of hormone target receptors. Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) is a new therapeutic approach that exploits the combination of an antibody directed against the Trop-2 antigen expressed in solid epithelial tumors and the active metabolite SN-38, to precisely target cancer cells. The development of consensus recommendations requires synthesizing expert opinions, especially when direct evidence is limited.

Methods

This study aimed to create a Delphi process to gather the perspectives of a panel of BC and supportive specialists on the use of SG in clinical practice. A scientific board discussed and defined a series of statements that were submitted to the panel through 2 rounds of voting. The process was designed to collect expert opinions to achieve consensus on key points regarding the safety, dosing regimens, and patient management for SG. Each round of the survey included targeted questions informed by current literature. Predefined criteria for consensus were set at ≥75% agreement.

Results

In October 2024, 29 experts’ opinions were collected by voting on 40 statements and reaching a 67% agreement. The reduction of the initial SG dose and the management of prophylaxis for patients with the UGT1A1 *28/*28 genotype were the most discussed topics.

Conclusions

The results provide a foundational framework for clinical decision-making, and highlight the importance of collaborative expert synthesis in forming practice guidelines. Future studies should focus on prospective SG trials to address the identified areas of uncertainty.

Our study provides insights into the side effects associated with Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) treatment in TNBC, offering a deeper understanding of their impact on patients. By discussing and characterizing these adverse effects, we can improve treatment management by enabling healthcare providers to better anticipate, monitor, and mitigate these side effects. Further research is needed to further investigate these findings and to explore the optimal management of SG-related adverse events.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer (11.7% of all cases) and the fifth most prevalent cause of death from cancer (6.9%) worldwide. Triple-negative BC (TNBC) is an aggressive subtype of BC, despite the fact that different new drugs have been approved in the treatment algorithm. The new diagnosis rates range from 15% to 20%. TNBC is characterized by a lack of expression of estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor as well as an absence of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) overexpression, and clinically it tends to develop nodal metastasis. It is well known that patients with TNBC develop a higher rate of metastases and are more likely to spread to the brain and lungs, as well as they have a higher risk of early relapse than those with other BC subtypes.1,2 Metastatic TNBC (mTNBC), due to the lack of target receptors and being a heterogeneous disease with few treatment options, is considered a clinical unmet need. Patients affected by mTNBC have typically poor clinical outcomes and, to date, chemotherapy (CT) has been the only systemic therapy available for patients with mTNBC. However, with the recent approvals of alternative therapeutic options such as the anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (anti-PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (pembro), poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor-based therapy and the anti-TROP-2 antibody-drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan (SG), clinical outcomes of mTNBC patients have significantly improved. Moreover, several clinical trials are ongoing for SG both as a single agent and in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors or PARPi.3,4 SG is an antineoplastic agent combining sacituzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody binding to trophoblast cell-surface antigen-2 (Trop-2)-expressing cancer cells, linked with govitecan (SN-38), a topoisomerase I inhibitor. In the European Union, in 2021 SG was approved as monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with unresectable or mTNBC who have previously received 2 or more systemic therapies, including at least one of them for advanced stage.5,6 The TNBC setting represents the initial and most established evidence in the literature regarding the use of SG. The first phase I/II study (IMMU-132-02) was conducted in patients with metastatic and refractory TNBC. The positive results related to the safety and good tolerability at the 8-10 mg/kg dose led, in 2020, to the prompt approval of SG by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with the consequent prospective to become a third-line treatment for patients with unresectable mTNBC who have previously received 2 or more systemic therapies.7 Subsequently, the phase III global, open-label randomized ASCENT trial demonstrated the significant superiority of SG over single-agent CT in terms of progression-free survival (PFS; median PFS [mPFS], 5.6 vs 1.7 months, respectively) and overall survival (OS; median OS [mOS], 12.1 vs 6.7 months, respectively). Furthermore, the overall response rate in the SG arm was 35% compared to 5% in the CT arm.8-10 In the ASCENT study, grade ≥3 adverse events (AEs) related to treatment with SG compared to standard CT were predominantly neutropenia (51% vs 33% in the SG vs CT group), leukopenia (10% vs 5%), diarrhea (10% vs <1%), anemia (8% vs 5%,), and febrile neutropenia (6% vs 2%). No severe cardiovascular toxicity, neuropathy, interstitial pulmonary disease (ILD), or deaths related to SG treatment were reported. In the phase III TROPICS 02 study, the most common treatment-related AEs of any grade with SG compared to standard CT were neutropenia (70% vs 54%), diarrhea (57% vs 16%), nausea (55% vs 31%), alopecia (46% vs 16%), fatigue (37% vs 29%) and anemia (34% vs 25%). For what concerns grade 3 or more AEs neutropenia (51% vs 38%), leukopenia (9% vs 5%), diarrhea (9% vs 1%), anemia (6% vs 3%), and fatigue (6% vs 2%), results were similar to previous studies. In addition, in the quality of life (QoL) assessment, SG achieved better results compared to CT.11,12 A large retro-prospective study investigating the safety and activity of SG in mTNBC patients from 24 Italian centers, further described a SG dose reduction in 37/94 patients (mean time to first reduction: 41 days dose delay), without new safety signals observed, and assessment of UGT1A1 status.13 The UGT1A1 gene is an important component for the metabolism and glucuronidation of certain drugs, including SG; therefore, various UGT1A1 polymorphisms leading to decreased function of the UGT1A1 enzyme may be responsible for the increased risk of treatment-related side effects. To improve SG treatment’s efficacy and reduce the frequency of significant AEs, correct evaluation and care are necessary. To date, very fragmentary real-world data (RWD) are available, and the level of evidence in mTNBC is still limited and conflicting. Given the extension of indications in BC and that in Italy SG is reimbursed by the Italian Drug Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA) only in the TNBC setting, proper management of AEs in the mTNBC subtype becomes crucial to guarantee treatment’s efficacy and safety. This paper aims to contribute professional experience and gain insights from a panel of oncology experts to manage AEs with SG and to provide further recommendations on the real-world management of SG in mTNBC.

Methods

In May 2024, a group of experts planned a collaboration to investigate the attitude of a selected panel of Italian professionals to manage the administration of SG in mTNBC and the related AEs. The project was designed based on rather limited evidence beyond the pivotal trials, mostly supported by individual clinical experiences on the use of the SG. The scientific board used the Delphi survey and consensus approach. Thirteen experts, including 10 oncologists (MDM, DS, AAV, GA, GB, LB, CC, AF, SP, and RF), one pharmacologist (RD), 2 geriatricians (AA, GC), established a scientific board responsible for:

Defining themes (items), statements and supervising all phases of the consensus process

Selecting the panel of specialists to be involved in the Delphi

Selecting the scientific literature for the definition of statements

Producing the outline and drafting of shared recommendations

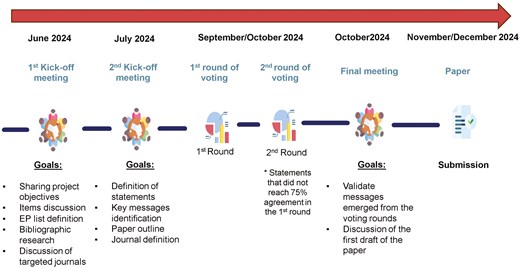

The expert panel (EP) was selected by the members of the Scientific Board and was composed of 51 Italian specialists from the oncology field. Respondents’ features (affiliation and specialty) are reported in Table S1. The board collaboratively developed a set of questions and statements on diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for managing AEs in SG-treated mTNBC patients, focusing on topics for which there was no high-quality evidence or available recommendations were conflicting. To compile the survey, the EP was involved in 2 rounds of voting through a dedicated online platform (https://consensusdelphi-mbreastcancer.wdemo.it/), and to guarantee adherence to the process they were invited by e-mail. Consent to participate was implied by registering and completing the online questionnaire. The answers to the questions were provided on a voluntary basis and all replies were anonymized in accordance with national and EU rules on the protection of the processing of personal and sensitive data (European Regulation n.679/2016, c.d. GDPR, and Italian legislation on Privacy). Each board member took part in the discussions on the statements and provided proposals and suggestions collected for the final outline. Based on their expertise, the scientific board summarized proposals in a first conception of the statements to be voted on, dealt with the methodological part of the project, and the analysis of the results. The timeline of the methodological process is shown in Figure 1.

Flowchart of the methodology design including editorial project, data collection, and final consensus paper definition; * Statements that did not reach 75% in the first round were subjected to a second round of voting.

The survey consisted of 7 questions and 40 statements, organized according to the various types of AEs associated with SG: hematopoietic toxicity (10 statements), gastrointestinal AEs (9 statements), fatigue (4 statements), management of dose modifications (9 statements), pharmacology and assessment of UGT1A1 polymorphisms (5 statements), liver toxicities (2 statements), and hypersensitivity (1 statement1). All healthcare professionals were asked to rate their strength of agreement with each statement on a 5-point scale: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), uncertain (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5), with the possibility of a notes field next to each question for an optional free-text comment. The final agreement percentage was calculated as the combined result of the votes including “agree” and “strongly agree.” The panel was asked to vote on all statements in order to submit the survey. Participants were also encouraged to contribute any comments to the statement in case of disagreement, in the free-text space. Answers were collected, reviewed and discussed by the project’s scientific board during the final meeting, to decide whether statements that had not reached a sufficient level of consensus should be modified to be resubmitted in a second round. Statements were evaluated as follows:

- If the agreement ≥75% (defined as the percentage of “agree” and “strongly agree”), the statement was accepted;

- If the agreement was >25% and <75%, the statement was not accepted and was eventually re-proposed in the subsequent round, and modified based on participants’ hints;

- If the agreement was ≤25%, the statement was not accepted.

For some statements, 2 rounds of voting were conducted. Descriptive analyses are detailed in the Results section and all questions and answers are summarized in Table 1.

List of final and most relevant statements for clinical practice divided by topic and questions, and relative percentages of consensus level achieved.

| Question . | Statement . | Agree, % . | Disagree, % . | Uncertain, % . | Level of consensus . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Management of hematopoietic toxicity14 | (a) Neutropenia | 1.1 Patients undergoing treatment with SG should be monitored for neutropenia, without any additional exams beyond those routinely performed before each administration. | 93.10 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance |

| 1.2 Primary prophylactic administration of G-CSF should be considered to mitigate the risk of severe neutropenia and to maintain adequate dose intensity, independently of risk factors | 59.1 | 22.7 | 18.2 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.3 If considered primary prophylaxis, the schedule should be the one used in the PRIMED trial (G-CSF 0.3 MU/kg/day SC QD on D3, D4, and D10, D11). | 48.3 | 20.7 | 31.0 | First round rejection | ||

| 1.5 Primary prophylactic use of G-CSF to maintain dose intensity should be considered for selected patients, like frail patients (eg, age, obesity, comorbidities). | 75.9 | 17.2 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.6 In patients with known homozygous UGT1A1 *28/*28, the primary prophylactic use of G-CSF should NOT be considered mandatory. | 54.5 | 9.1 | 36.4 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.7 Secondary prophylaxis should be considered at the first appearance of grade 4 neutropenia lasting 7 or more days, febrile neutropenia or grade 3-4 neutropenia that delayed administration by 2 or 3 weeks for recovery to grade ≤1. | 86.2 | 10.3 | 3.5 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.8 In case of febrile neutropenia, despite of prophylaxis with G-CSF, dose reduction has to be considered. | 89.7 | 6.9 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.9 A prospective multinational study validated the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk-index (MASCC) score. The score >21 identified low-risk patients with a positive predictive value of 91%, specificity of 68%, and sensitivity of 71%. MASCC score for the management of febrile neutropenia should be recommended in all patients to choice those that need of hospital admission to avoid life-threatening event15 | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2. Management of gastrointestinal adverse events | (a) Nausea16 | 2.1 The 3-drug regimen (5-HT3 + NK-1i + dex in second and third day) for the prevention of SG nausea and vomiting is the referral treatment choice from the first cycle of SG. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance |

| 2.2 Physician should be confident with the use of Olanzapine in case of refractory or anticipatory nausea and vomiting. | 79.3 | 3.5 | 17.2 | First round acceptance | ||

| (b) Diarrhea14 | 2.3 Primary prophylaxis with loperamide should not be considered to prevent diarrhea. | 65.6 | 17.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | |

| 2.4 In patients at high risk of diarrhea (ie, previuos GI toxicity, IBD, other GI conditions), primary prophylaxis with loperamide should be considered. | 51.7 | 13.8 | 34.5 | First round rejection | ||

| 2.5 In the management of any grade diarrhea, loperamide should be administered as a standard treatment to prevent and reduce incidence and severity. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| (c) Cholinergic Syndrome and acute diarrhea | 2.7 Routine anticholinergic prophylaxis (ie, Atropine Injections) is not recommended in patients who have never suffered from diarrhea. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 2.8 In case of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome (abdominal cramps, diarrhea, sweating or excessive salivation) during or shortly after infusion of SG, the patient should be treated with atropine 0.4 mg intravenously every 15 minutes (for 2 doses if necessary). Subsequent doses of atropine 0.2 mg intravenously may also be administered, for a total of 1 mg. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2.9 In case of one episode of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome, additional prophylaxis with atropine should be used for all subsequent infusions. | 86.2 | 3.5 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 3. Management of fatigue | 3.1 Fatigue should be evaluated at each clinical visit with standardized fatigue assessment tools (eg, FACIT-F, Brief Fatigue Inventory). | 79.4 | 10.3 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 3.2 Physical exercise and behavioral cognitive approach may be suggested to reduce SG-related fatigue of grade NRS ≥4. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1 | ||||||

| 4. Management of dose modifications or delays | (a) All population17 | 4.2 Temporary delay of the cycle start may be necessary to manage AEs. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance |

| 4.3 Dose reduction and delay, when performed according to technical label, do not impact negatively the drug’s efficacy. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.4 Dose reduction of SG upfront is not mandatory for homozygous UGT1A1 genotype *28/*28. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.5 SG should be administered at the full dose during the first cycle, with rare exceptions, as reducing the dose could negatively impact treatment efficacy. | 72.4 | 13.8 | 13.8 | First round rejection | ||

| (b) Frail and elderly patients SABCS18 | 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in fragile patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 31.8 | 54.6 | 13.6 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | |

| 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in frail patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 54.5 | 36.4 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 36.4 | 59.1 | 4.5 | Second and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 68.2 | 22.7 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 5. Pharmacology and assessment of UGT1A1 polymorphisms19 | 5.1 The routine testing of UGT1A1 polymorphisms is not recommended due to inconsistent data on cost-effectiveness as the initial dose/toxicity management from SG is independent of UGT1A1 status. | 79.3 | 6.9 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | |

| 5.2 Assessment of UGT1A1 status is recommended before starting therapy with SG ONLY in frail patients, regardless of age. | 24.2 | 27.6 | 48.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.3 In patients with wild-type UGT1A1 polymorphism, in the presence of potential drug interactions, but in the absence of adverse reactions, dose reduction is not justified. | 82.8 | 6.9 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 5.4 The risk of major adverse events with SG is not influenced by drug interactions. | 58.6 | 24.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.5 The analysis of plasma levels of SN-38 is not required as a drug-monitoring approach to improve the safety of SG. | 89.7 | 3.4 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 6. Management of liver toxicities | 6.1 In patients with Gilbert’s syndrome, the use of SG should be prudentially excluded. | 20.7 | 58.6 | 20.7 | First round rejection | |

| 6.2 In absence of a strong evidence, the use of SG could be considered in selected patients with Gilbert’s syndrome. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 7. Management of hypersensitivity | 7.1 In case of severe hypersensitivity, a steroid and antihistamine premedication could be considered, instead of a discontinuation of treatment. | 79.3 | 17.3 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | |

| Question . | Statement . | Agree, % . | Disagree, % . | Uncertain, % . | Level of consensus . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Management of hematopoietic toxicity14 | (a) Neutropenia | 1.1 Patients undergoing treatment with SG should be monitored for neutropenia, without any additional exams beyond those routinely performed before each administration. | 93.10 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance |

| 1.2 Primary prophylactic administration of G-CSF should be considered to mitigate the risk of severe neutropenia and to maintain adequate dose intensity, independently of risk factors | 59.1 | 22.7 | 18.2 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.3 If considered primary prophylaxis, the schedule should be the one used in the PRIMED trial (G-CSF 0.3 MU/kg/day SC QD on D3, D4, and D10, D11). | 48.3 | 20.7 | 31.0 | First round rejection | ||

| 1.5 Primary prophylactic use of G-CSF to maintain dose intensity should be considered for selected patients, like frail patients (eg, age, obesity, comorbidities). | 75.9 | 17.2 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.6 In patients with known homozygous UGT1A1 *28/*28, the primary prophylactic use of G-CSF should NOT be considered mandatory. | 54.5 | 9.1 | 36.4 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.7 Secondary prophylaxis should be considered at the first appearance of grade 4 neutropenia lasting 7 or more days, febrile neutropenia or grade 3-4 neutropenia that delayed administration by 2 or 3 weeks for recovery to grade ≤1. | 86.2 | 10.3 | 3.5 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.8 In case of febrile neutropenia, despite of prophylaxis with G-CSF, dose reduction has to be considered. | 89.7 | 6.9 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.9 A prospective multinational study validated the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk-index (MASCC) score. The score >21 identified low-risk patients with a positive predictive value of 91%, specificity of 68%, and sensitivity of 71%. MASCC score for the management of febrile neutropenia should be recommended in all patients to choice those that need of hospital admission to avoid life-threatening event15 | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2. Management of gastrointestinal adverse events | (a) Nausea16 | 2.1 The 3-drug regimen (5-HT3 + NK-1i + dex in second and third day) for the prevention of SG nausea and vomiting is the referral treatment choice from the first cycle of SG. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance |

| 2.2 Physician should be confident with the use of Olanzapine in case of refractory or anticipatory nausea and vomiting. | 79.3 | 3.5 | 17.2 | First round acceptance | ||

| (b) Diarrhea14 | 2.3 Primary prophylaxis with loperamide should not be considered to prevent diarrhea. | 65.6 | 17.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | |

| 2.4 In patients at high risk of diarrhea (ie, previuos GI toxicity, IBD, other GI conditions), primary prophylaxis with loperamide should be considered. | 51.7 | 13.8 | 34.5 | First round rejection | ||

| 2.5 In the management of any grade diarrhea, loperamide should be administered as a standard treatment to prevent and reduce incidence and severity. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| (c) Cholinergic Syndrome and acute diarrhea | 2.7 Routine anticholinergic prophylaxis (ie, Atropine Injections) is not recommended in patients who have never suffered from diarrhea. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 2.8 In case of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome (abdominal cramps, diarrhea, sweating or excessive salivation) during or shortly after infusion of SG, the patient should be treated with atropine 0.4 mg intravenously every 15 minutes (for 2 doses if necessary). Subsequent doses of atropine 0.2 mg intravenously may also be administered, for a total of 1 mg. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2.9 In case of one episode of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome, additional prophylaxis with atropine should be used for all subsequent infusions. | 86.2 | 3.5 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 3. Management of fatigue | 3.1 Fatigue should be evaluated at each clinical visit with standardized fatigue assessment tools (eg, FACIT-F, Brief Fatigue Inventory). | 79.4 | 10.3 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 3.2 Physical exercise and behavioral cognitive approach may be suggested to reduce SG-related fatigue of grade NRS ≥4. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1 | ||||||

| 4. Management of dose modifications or delays | (a) All population17 | 4.2 Temporary delay of the cycle start may be necessary to manage AEs. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance |

| 4.3 Dose reduction and delay, when performed according to technical label, do not impact negatively the drug’s efficacy. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.4 Dose reduction of SG upfront is not mandatory for homozygous UGT1A1 genotype *28/*28. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.5 SG should be administered at the full dose during the first cycle, with rare exceptions, as reducing the dose could negatively impact treatment efficacy. | 72.4 | 13.8 | 13.8 | First round rejection | ||

| (b) Frail and elderly patients SABCS18 | 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in fragile patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 31.8 | 54.6 | 13.6 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | |

| 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in frail patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 54.5 | 36.4 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 36.4 | 59.1 | 4.5 | Second and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 68.2 | 22.7 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 5. Pharmacology and assessment of UGT1A1 polymorphisms19 | 5.1 The routine testing of UGT1A1 polymorphisms is not recommended due to inconsistent data on cost-effectiveness as the initial dose/toxicity management from SG is independent of UGT1A1 status. | 79.3 | 6.9 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | |

| 5.2 Assessment of UGT1A1 status is recommended before starting therapy with SG ONLY in frail patients, regardless of age. | 24.2 | 27.6 | 48.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.3 In patients with wild-type UGT1A1 polymorphism, in the presence of potential drug interactions, but in the absence of adverse reactions, dose reduction is not justified. | 82.8 | 6.9 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 5.4 The risk of major adverse events with SG is not influenced by drug interactions. | 58.6 | 24.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.5 The analysis of plasma levels of SN-38 is not required as a drug-monitoring approach to improve the safety of SG. | 89.7 | 3.4 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 6. Management of liver toxicities | 6.1 In patients with Gilbert’s syndrome, the use of SG should be prudentially excluded. | 20.7 | 58.6 | 20.7 | First round rejection | |

| 6.2 In absence of a strong evidence, the use of SG could be considered in selected patients with Gilbert’s syndrome. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 7. Management of hypersensitivity | 7.1 In case of severe hypersensitivity, a steroid and antihistamine premedication could be considered, instead of a discontinuation of treatment. | 79.3 | 17.3 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | |

In the first round of voting, 4.6*/** and 4.7*/** statements were 2 distinct statements, which were separated based on the 2 proposed hypotheses.

List of final and most relevant statements for clinical practice divided by topic and questions, and relative percentages of consensus level achieved.

| Question . | Statement . | Agree, % . | Disagree, % . | Uncertain, % . | Level of consensus . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Management of hematopoietic toxicity14 | (a) Neutropenia | 1.1 Patients undergoing treatment with SG should be monitored for neutropenia, without any additional exams beyond those routinely performed before each administration. | 93.10 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance |

| 1.2 Primary prophylactic administration of G-CSF should be considered to mitigate the risk of severe neutropenia and to maintain adequate dose intensity, independently of risk factors | 59.1 | 22.7 | 18.2 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.3 If considered primary prophylaxis, the schedule should be the one used in the PRIMED trial (G-CSF 0.3 MU/kg/day SC QD on D3, D4, and D10, D11). | 48.3 | 20.7 | 31.0 | First round rejection | ||

| 1.5 Primary prophylactic use of G-CSF to maintain dose intensity should be considered for selected patients, like frail patients (eg, age, obesity, comorbidities). | 75.9 | 17.2 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.6 In patients with known homozygous UGT1A1 *28/*28, the primary prophylactic use of G-CSF should NOT be considered mandatory. | 54.5 | 9.1 | 36.4 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.7 Secondary prophylaxis should be considered at the first appearance of grade 4 neutropenia lasting 7 or more days, febrile neutropenia or grade 3-4 neutropenia that delayed administration by 2 or 3 weeks for recovery to grade ≤1. | 86.2 | 10.3 | 3.5 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.8 In case of febrile neutropenia, despite of prophylaxis with G-CSF, dose reduction has to be considered. | 89.7 | 6.9 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.9 A prospective multinational study validated the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk-index (MASCC) score. The score >21 identified low-risk patients with a positive predictive value of 91%, specificity of 68%, and sensitivity of 71%. MASCC score for the management of febrile neutropenia should be recommended in all patients to choice those that need of hospital admission to avoid life-threatening event15 | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2. Management of gastrointestinal adverse events | (a) Nausea16 | 2.1 The 3-drug regimen (5-HT3 + NK-1i + dex in second and third day) for the prevention of SG nausea and vomiting is the referral treatment choice from the first cycle of SG. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance |

| 2.2 Physician should be confident with the use of Olanzapine in case of refractory or anticipatory nausea and vomiting. | 79.3 | 3.5 | 17.2 | First round acceptance | ||

| (b) Diarrhea14 | 2.3 Primary prophylaxis with loperamide should not be considered to prevent diarrhea. | 65.6 | 17.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | |

| 2.4 In patients at high risk of diarrhea (ie, previuos GI toxicity, IBD, other GI conditions), primary prophylaxis with loperamide should be considered. | 51.7 | 13.8 | 34.5 | First round rejection | ||

| 2.5 In the management of any grade diarrhea, loperamide should be administered as a standard treatment to prevent and reduce incidence and severity. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| (c) Cholinergic Syndrome and acute diarrhea | 2.7 Routine anticholinergic prophylaxis (ie, Atropine Injections) is not recommended in patients who have never suffered from diarrhea. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 2.8 In case of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome (abdominal cramps, diarrhea, sweating or excessive salivation) during or shortly after infusion of SG, the patient should be treated with atropine 0.4 mg intravenously every 15 minutes (for 2 doses if necessary). Subsequent doses of atropine 0.2 mg intravenously may also be administered, for a total of 1 mg. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2.9 In case of one episode of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome, additional prophylaxis with atropine should be used for all subsequent infusions. | 86.2 | 3.5 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 3. Management of fatigue | 3.1 Fatigue should be evaluated at each clinical visit with standardized fatigue assessment tools (eg, FACIT-F, Brief Fatigue Inventory). | 79.4 | 10.3 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 3.2 Physical exercise and behavioral cognitive approach may be suggested to reduce SG-related fatigue of grade NRS ≥4. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1 | ||||||

| 4. Management of dose modifications or delays | (a) All population17 | 4.2 Temporary delay of the cycle start may be necessary to manage AEs. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance |

| 4.3 Dose reduction and delay, when performed according to technical label, do not impact negatively the drug’s efficacy. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.4 Dose reduction of SG upfront is not mandatory for homozygous UGT1A1 genotype *28/*28. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.5 SG should be administered at the full dose during the first cycle, with rare exceptions, as reducing the dose could negatively impact treatment efficacy. | 72.4 | 13.8 | 13.8 | First round rejection | ||

| (b) Frail and elderly patients SABCS18 | 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in fragile patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 31.8 | 54.6 | 13.6 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | |

| 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in frail patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 54.5 | 36.4 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 36.4 | 59.1 | 4.5 | Second and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 68.2 | 22.7 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 5. Pharmacology and assessment of UGT1A1 polymorphisms19 | 5.1 The routine testing of UGT1A1 polymorphisms is not recommended due to inconsistent data on cost-effectiveness as the initial dose/toxicity management from SG is independent of UGT1A1 status. | 79.3 | 6.9 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | |

| 5.2 Assessment of UGT1A1 status is recommended before starting therapy with SG ONLY in frail patients, regardless of age. | 24.2 | 27.6 | 48.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.3 In patients with wild-type UGT1A1 polymorphism, in the presence of potential drug interactions, but in the absence of adverse reactions, dose reduction is not justified. | 82.8 | 6.9 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 5.4 The risk of major adverse events with SG is not influenced by drug interactions. | 58.6 | 24.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.5 The analysis of plasma levels of SN-38 is not required as a drug-monitoring approach to improve the safety of SG. | 89.7 | 3.4 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 6. Management of liver toxicities | 6.1 In patients with Gilbert’s syndrome, the use of SG should be prudentially excluded. | 20.7 | 58.6 | 20.7 | First round rejection | |

| 6.2 In absence of a strong evidence, the use of SG could be considered in selected patients with Gilbert’s syndrome. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 7. Management of hypersensitivity | 7.1 In case of severe hypersensitivity, a steroid and antihistamine premedication could be considered, instead of a discontinuation of treatment. | 79.3 | 17.3 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | |

| Question . | Statement . | Agree, % . | Disagree, % . | Uncertain, % . | Level of consensus . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Management of hematopoietic toxicity14 | (a) Neutropenia | 1.1 Patients undergoing treatment with SG should be monitored for neutropenia, without any additional exams beyond those routinely performed before each administration. | 93.10 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance |

| 1.2 Primary prophylactic administration of G-CSF should be considered to mitigate the risk of severe neutropenia and to maintain adequate dose intensity, independently of risk factors | 59.1 | 22.7 | 18.2 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.3 If considered primary prophylaxis, the schedule should be the one used in the PRIMED trial (G-CSF 0.3 MU/kg/day SC QD on D3, D4, and D10, D11). | 48.3 | 20.7 | 31.0 | First round rejection | ||

| 1.5 Primary prophylactic use of G-CSF to maintain dose intensity should be considered for selected patients, like frail patients (eg, age, obesity, comorbidities). | 75.9 | 17.2 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.6 In patients with known homozygous UGT1A1 *28/*28, the primary prophylactic use of G-CSF should NOT be considered mandatory. | 54.5 | 9.1 | 36.4 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 1.7 Secondary prophylaxis should be considered at the first appearance of grade 4 neutropenia lasting 7 or more days, febrile neutropenia or grade 3-4 neutropenia that delayed administration by 2 or 3 weeks for recovery to grade ≤1. | 86.2 | 10.3 | 3.5 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.8 In case of febrile neutropenia, despite of prophylaxis with G-CSF, dose reduction has to be considered. | 89.7 | 6.9 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1.9 A prospective multinational study validated the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk-index (MASCC) score. The score >21 identified low-risk patients with a positive predictive value of 91%, specificity of 68%, and sensitivity of 71%. MASCC score for the management of febrile neutropenia should be recommended in all patients to choice those that need of hospital admission to avoid life-threatening event15 | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2. Management of gastrointestinal adverse events | (a) Nausea16 | 2.1 The 3-drug regimen (5-HT3 + NK-1i + dex in second and third day) for the prevention of SG nausea and vomiting is the referral treatment choice from the first cycle of SG. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance |

| 2.2 Physician should be confident with the use of Olanzapine in case of refractory or anticipatory nausea and vomiting. | 79.3 | 3.5 | 17.2 | First round acceptance | ||

| (b) Diarrhea14 | 2.3 Primary prophylaxis with loperamide should not be considered to prevent diarrhea. | 65.6 | 17.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | |

| 2.4 In patients at high risk of diarrhea (ie, previuos GI toxicity, IBD, other GI conditions), primary prophylaxis with loperamide should be considered. | 51.7 | 13.8 | 34.5 | First round rejection | ||

| 2.5 In the management of any grade diarrhea, loperamide should be administered as a standard treatment to prevent and reduce incidence and severity. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | ||

| (c) Cholinergic Syndrome and acute diarrhea | 2.7 Routine anticholinergic prophylaxis (ie, Atropine Injections) is not recommended in patients who have never suffered from diarrhea. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 2.8 In case of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome (abdominal cramps, diarrhea, sweating or excessive salivation) during or shortly after infusion of SG, the patient should be treated with atropine 0.4 mg intravenously every 15 minutes (for 2 doses if necessary). Subsequent doses of atropine 0.2 mg intravenously may also be administered, for a total of 1 mg. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 2.9 In case of one episode of acute diarrhea or early cholinergic syndrome, additional prophylaxis with atropine should be used for all subsequent infusions. | 86.2 | 3.5 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 3. Management of fatigue | 3.1 Fatigue should be evaluated at each clinical visit with standardized fatigue assessment tools (eg, FACIT-F, Brief Fatigue Inventory). | 79.4 | 10.3 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | |

| 3.2 Physical exercise and behavioral cognitive approach may be suggested to reduce SG-related fatigue of grade NRS ≥4. | 89.7 | 0 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 1 | ||||||

| 4. Management of dose modifications or delays | (a) All population17 | 4.2 Temporary delay of the cycle start may be necessary to manage AEs. | 93.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | First round acceptance |

| 4.3 Dose reduction and delay, when performed according to technical label, do not impact negatively the drug’s efficacy. | 93.1 | 0 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.4 Dose reduction of SG upfront is not mandatory for homozygous UGT1A1 genotype *28/*28. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 4.5 SG should be administered at the full dose during the first cycle, with rare exceptions, as reducing the dose could negatively impact treatment efficacy. | 72.4 | 13.8 | 13.8 | First round rejection | ||

| (b) Frail and elderly patients SABCS18 | 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in fragile patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 31.8 | 54.6 | 13.6 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | |

| 4.6 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients not represented in the clinical trials, particularly in frail patients due to the presence of multiple comorbidities. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 54.5 | 36.4 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It should be considered that in Italy, according to the AIFA data sheet, the first dose cannot be reduced.* | 36.4 | 59.1 | 4.5 | Second and rejection | ||

| 4.7 Although non-evidence-based, a reduction in the initial dose of SG, with adjustments in subsequent cycles in relation to the reported toxicity profile, may be considered in the subgroups of patients poorly represented in clinical studies (patients over 75 or at risk of fragility) to minimize gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity. Subsequent dose adjustments should be based on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy. It is assumed that AIFA allows to reduce the doses of the first administration ** | 68.2 | 22.7 | 9.1 | Second-round resubmission and rejection | ||

| 5. Pharmacology and assessment of UGT1A1 polymorphisms19 | 5.1 The routine testing of UGT1A1 polymorphisms is not recommended due to inconsistent data on cost-effectiveness as the initial dose/toxicity management from SG is independent of UGT1A1 status. | 79.3 | 6.9 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | |

| 5.2 Assessment of UGT1A1 status is recommended before starting therapy with SG ONLY in frail patients, regardless of age. | 24.2 | 27.6 | 48.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.3 In patients with wild-type UGT1A1 polymorphism, in the presence of potential drug interactions, but in the absence of adverse reactions, dose reduction is not justified. | 82.8 | 6.9 | 10.3 | First round acceptance | ||

| 5.4 The risk of major adverse events with SG is not influenced by drug interactions. | 58.6 | 24.2 | 17.2 | First round rejection | ||

| 5.5 The analysis of plasma levels of SN-38 is not required as a drug-monitoring approach to improve the safety of SG. | 89.7 | 3.4 | 6.9 | First round acceptance | ||

| 6. Management of liver toxicities | 6.1 In patients with Gilbert’s syndrome, the use of SG should be prudentially excluded. | 20.7 | 58.6 | 20.7 | First round rejection | |

| 6.2 In absence of a strong evidence, the use of SG could be considered in selected patients with Gilbert’s syndrome. | 82.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | First round acceptance | ||

| 7. Management of hypersensitivity | 7.1 In case of severe hypersensitivity, a steroid and antihistamine premedication could be considered, instead of a discontinuation of treatment. | 79.3 | 17.3 | 3.4 | First round acceptance | |

In the first round of voting, 4.6*/** and 4.7*/** statements were 2 distinct statements, which were separated based on the 2 proposed hypotheses.

Results

In the beginning, 7 topics and 40 statements were identified and sent to the 51 panelists (BC experts). Among them, 29 out of 51 (56.9%) members adhered to the consensus and 9 out of 29 (31%) expressed their opinion through a comment for some statements. In the hematopoietic toxicity setting, 9 statements were formulated about neutropenia and 1 statement was formulated about anemia; of these, 6 statements (60%) reached an agreement >75% after the first vote, 2 statements (20%) were rejected and 2 statements (20%) were readjusted based on the panelists’ review, in order to be resubmitted to the second round of voting. The 2 resubmitted statements did not reach the percentage of agreement even in the second round of voting, so the percentage of accepted statements was 60%. For what concerns gastrointestinal AEs, 2 statements were formulated about nausea, 4 about diarrhea, and 3 about the cholinergic syndrome and acute diarrhea; of these, 7 statements (78%) reached an agreement >75% after the first vote and 2 statements (22%) were rejected. In accordance with the management of fatigue, 4 statements were submitted, and all of them reached an agreement >75% after the first vote (100%). In the management of dose modifications or delays, 5 statements were formulated referring to the all population, and 4 statements focused on frail and elderly patients; of these, 6 statements (67%) reached an agreement >75% after the first vote, 1 statement (11%) was rejected and 2 statements (22%) were reworded based on the panelists’ review and divided into 2 separate statements, each with the same content but with different hypothesis regarding the modifiable dose of the drug. The 2 resubmitted statements did not reach the percentage of agreement even in the second round of voting, so the final percentage of accepted statements was 54.5%. In the setting of pharmacology and assessment of UGT1A1 polymorphisms, 5 statements were subjected to vote, and 3 of them (60%) reached an agreement >75% after the first vote, while 2 were rejected (40%). In the management of liver toxicities, 2 statements were submitted, and among these 1 (50%) reached an agreement >75% after the first vote, and 1 (50%) of them was rejected. In the setting of the management of hypersensitivity, the only submitted statement reached the agreement percentage >75% (100%). Overall, 40 statements were submitted, of which 28 (70%) achieved the percentage of agreement, 8 (20%) were rejected and 4 (10%) were resubmitted to a second round of voting based on the hints that emerged during the first round. In the new round of voting, 22 out of 29 panel members (75.9%) answered, and the statements were rejected, therefore the final percentage of accepted statements was 67%. The details of the percentages of consensus reached or not are reported in Table 1, which describes the most clinically significant statements. A summary of all questions submitted and statements preceding the reworded ones, as well as existing literature for each context, is available in Appendix A of supplementary data. The final consensus level achieved is reported in Table S2 of Appendix A.

Discussion

mTNBC is characterized by a dismal prognosis, especially in older patients, due to the poor tolerance to standard therapeutic regimens and multiple comorbidities that further complicate the management. To date, depending on the severity and context of the disease, patients with mTNBC can receive treatments with increasingly effective and targeted therapies, aiming to prolong survival, improve QoL, and counteract severe AEs. Therefore, the EP is based on the available scientific data specific to TNBC to ensure evidence-based recommendations. New treatment options can be associated with an easily manageable safety profile, but it is necessary to carefully monitor toxicity, including long-term AEs, to recognize and prevent them adequately. In particular, prospective data on managing drug toxicity in elderly and frail patients is essential for improving clinical outcomes. These populations are often underrepresented in clinical trials, resulting in limited evidence on how SG affects them specifically. In the ASCENT trial, Bardia et al. described longer OS and PFS with SG than with single-agent CT among patients with refractory TNBC, with a manageable safety profile consistent across all subgroups, and 35% responsive patients after SG compared to 5% of patients after CT.20,21 SG has definitively demonstrated favorable clinical activity in BC, and the FDA has granted accelerated its approval for a standard dose of 10 mg/kg. Studies indicate that the current dose, administered intravenously on days 1 and 8 of 21-day cycles, is safe and effective, and supports the appropriateness of the current monotherapy dosing regimen in the approved mTNBC indication, but with a higher incidence of AEs than CT; of particular concern is the higher incidence of neutropenia and diarrhea, which sometimes cause discontinuation of SG therapy. The handling of hematopoietic growth factors and other prophylactic measures is common, although there are no standardized guidelines for SG- associated AEs.7,22 RWD describes that blood and lymphatic system disorders, along with gastrointestinal ones, are the most frequently reported AEs associated with SG, as well as geriatric patients >65 years old are at an increased risk of developing neutropenic colitis, neutropenic sepsis, acute kidney injury, and atrial fibrillation.23 According to common clinical practice in Italy, RWD reveal that both the safety and efficacy of SG in the mTNBC setting are consistent with previously regulatory studies, with the most common related AE including anemia, alopecia, nausea, diarrhea, and the most serious neutropenia grade 3 (21.0% of patients) or 4 (8.7% of patients). Furthermore, 38.6% of patients underwent a dose reduction, and 5.3% discontinued therapy permanently.24 The major uncertainties/controversies in AE management have been identified and discussed, focusing primarily on unmet clinical issues or insufficient evidence.

Management of hematopoietic toxicity

Neutropenia

The panelists agree that patients subject to treatment with SG should be monitored for neutropenia, the most common AE. Analysis from the phase II PRIMED clinical trial assessed the feasibility of primary prophylaxis with Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF) and loperamide to improve the tolerability of SG and ultimately decrease treatment modifications. The trial revealed that prophylactic administration of G-CSF and loperamide resulted in a clinically relevant reduction in the incidence and severity of SG-related neutropenia and diarrhea, helping mitigate dose reductions and treatment interruptions.14 In the management of severe neutropenia, the use of G-CSF as prophylaxis is not a common attitude, and the percentages of disagreement and uncertainty among the panelists demonstrate that many experts are not inclined to its use. The panel raised major concerns while offering interesting insights. It would be interesting to evaluate whether the rates of hematological and gastrointestinal toxicity are confirmed in young and second-line patients, for whom treatment generally seems to be better tolerated. The responders agreed on a dose reduction in case of febrile neutropenia, and secondary prophylaxis in case of the appearance of grade 4 neutropenia lasting 7 or more days, febrile neutropenia, or grade 3-4 neutropenia that delay administration by 2 or 3 weeks for recovery to grade ≤1. Conversely, no sufficient consensus was reached for the clinical use of specific schedules of G-CSF, as PRIMED and MASCC ones, leaving open the issue of personalization of the treatment schedule. Experts were cautious and not confident both regarding the PRIMED scheme (31% of uncertain opinions) and the MASCC scheme (27.6% of uncertain opinions), and doubts persisted even if not considering the possible risk factors, as aroused from the second round of voting. Some patients may need to be supported with G-CSF after day 8 for many days, due to the development of delayed neutropenia, while other experts reported that the administration of G-CSF after day 1 is sufficient, making it necessary to identify the correct program and time of prophylaxis based on personalized schedules. The MASCC scheme was not accepted unanimously by the panel, due to concerns about the specific needs of the patient, while the MASCC score for febrile neutropenia has been recommended for the selection of all patients requiring hospitalization to avoid life-threatening events.15

UGT1A1 polymorphisms assessment

In the management of individuals with known homozygous UGT1A1 *28/*28 treated with SG, concerns persisted about the primary prophylactic use of G-CSF. The panel highlighted that UGT1A1 *28/*28 is not routinely performed, therefore suggesting that primary G-CSF prophylaxis can be used in patients as per clinical practice, but 36.4% of voters were still unsure about how to proceed. Subjects with a known homozygous *28/*28 genotype should be carefully monitored for neutropenia, although no specific recommendations are available. Patients with the *28 homozygous genotype had a slightly higher rate of grade ≥3 treatment-related neutropenia (59%) than those with heterozygous (47%) and wild-type (53%) genotypes, but a considerably higher rate of treatment-related grade ≥3 febrile neutropenia (18% vs 5% and 3%, respectively). Grade ≥3 treatment-related anemia (15% vs 6% and 4%, respectively) and grade ≥3 treatment-related diarrhea (15% vs 9% and 10%, respectively) are also more common in patients with the *28 homozygous genotype.19 The influence of the UGT1A1*28 genotype in clinical trials has been evaluated, but even if SG has conferred good clinical activity and minimal AEs, due to the limited number of studies with available UGT1A1 genotype data, its potential utility in predicting the safety profile is still difficult to determine.25 According to the technical label, patients with known reduced activity of UGT1A1 should be closely monitored for any AEs, otherwise, UGT1A1 status is not required and, according to the panelists, dose reduction of SG is not mandatory for UGT1A1 genotype *28/*28 patients. The FDA-approved drug label states; however, that UGT1A1*28 homozygotes have an increased risk of neutropenia, but with limited and missing data.26

Management of liver toxicity

Gilbert’s syndrome

Gilbert’s syndrome (GS) is a mild liver disorder caused by an inherited deficiency in the enzyme UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, which is responsible for processing bilirubin. This results in elevated levels of unconjugated bilirubin in the bloodstream, leading to intermittent jaundice in some individuals. Despite its relatively benign nature, patients with GS are often excluded from clinical trials.27 The board paid particular attention to the management of the disease, and the panel agreed that SG use in patients with GS, particularly those with total bilirubin levels below 3 mg/dL, may be considered, as it does not represent an absolute contraindication. However, SG should be considered carefully in GS patients with UGT *28/*28, and monitoring is essential due to the liver’s role in drug metabolism and the potential for bilirubin levels to fluctuate. Although Gilbert’s disease is a benign condition typically characterized by mild hyperbilirubinemia, the underlying impairment in glucuronidation may influence the pharmacokinetics of certain drugs. Excluding individuals with Gilbert’s syndrome from clinical trials means that the results may not fully represent the diversity of the population, and it could limit the generalizability of results and the understanding of how such individuals might respond to SG.

Management of dose modifications or delays

All population

In the ASCENT trial, treatment interruptions occurred in 61% and 33% of patients in the SG and TPC arms, and dose reductions occurred in 26% and 22%, respectively, although efficacy results are almost comparable in the 2 groups. Reinisch et al. supported the strategy of initial dose reduction in elderly patients to manage toxicity, improving overall treatment tolerance and outcomes.17 However, the panelists declared that SG should be administered at the full dose during the first cycle in all patients, with rare exceptions, even if this statement was at the edge of the agreement threshold due to some concerns related to efficacy.

Frail and elderly patients

With regard to initial dose reductions in frail and elderly patients, even assuming that restrictions by AIFA, imposing full dose at treatment start, could be ignored and that initial dose reduction is allowed, the agreement percentages increased but did not reach consensus. This highlights that there is still resistance among clinicians since primary dose reductions should be considered carefully due to a lack of data correlating effects and efficacy. Data from the ASCENT study show that patients ≥65 or ≥75 years of age treated with SG generally have similar safety profiles to those <65 years, with a similar rate of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs; all grades and grade ≥3). TRAEs leading to dose reduction were generally similar across treatment arms, and no treatment-related deaths were reported. New TROPiCS-02 data revealed a favorable benefit/risk profile in older patients, supporting the use of SG versus CT in this patient population, which is known to experience greater toxicity and lower efficacy with CT.18 Interestingly, the impact of body mass index (BMI) was assessed for SG treatment, which proved efficacy compared to CT and with a manageable safety profile across all BMI subgroups assessed by ASCENT. Although a greater proportion of patients with high BMI (particularly obese patients) experienced dose reduction of SG, this did not translate into a decrease in efficacy.28

Management of fatigue

The acceptance of the fatigue statement is a significant step forward in raising awareness among clinicians about a topic often overlooked or underappreciated in practice. Fatigue should be evaluated at each clinical visit with standardized fatigue assessment tools (eg, FACIT-F, Brief Fatigue Inventory), although some panelists emphasized that the assessment of fatigue at each visit/cycle could be excessive and does not reflect real clinical practice. These questionnaires emphasize the need for greater efforts to ensure that such tools are effectively utilized in clinical settings, where they can make a tangible impact on patient care and outcomes.

Management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and gastrointestinal AEs

Regarding chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting prevention and management, according to MASCC/ESMO guidelines, for patients undergoing some systemic cancer treatment of moderate emetic potential, such as carboplatin (AUC ≥ 5) and women <50 years of age receiving oxaliplatin-based treatment, emetic prophylaxis should be based on a triple combination of neurokinin (NK)1 receptor antagonist, 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, and steroids.16 A double combination of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and steroids remains the recommended prophylaxis for other systemic cancer treatments of moderate emetic potential. To date, based on the literature search, SG and trastuzumab deruxtecan should be categorized at the upper range of the moderate emetic risk classification, comparable to carboplatin >AUC 5.16 Additionally, clinicians seem to have confidence in using olanzapine for refractory or anticipatory nausea and vomiting. However, this data should be interpreted with caution, primarily due to potential side effects associated with the drug, as emerged from some experts. Discordant results still reflect the poor attitude towards the use of prophylactic loperamide, as approximately half of the voters were uncertain about the possibility of primary administration to prevent diarrhea, even for high-risk patients, for example, in inflammatory bowel disease patients, while it is commonly used as a treatment of any grade diarrhea.

Conclusions

This consensus seeks to bridge existing knowledge gaps by providing practical recommendations that encompass both well-documented and lesser-known side effects of SG. The uncertainty surrounding the efficacy and safety of SG-related AEs highlights the need for further randomized studies. Future efforts should focus on integrating more clinical data and promoting comprehensive research to further validate and enrich these initial findings. In summary, while this consensus-building initiative represents an essential first step toward the informed use of SG and enhanced clinician awareness of its adverse effects, continued investigation and broader expert engagement are imperative to bolster its impact and reliability.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support in the preparation of this article was provided by Erika Bandini, MD on behalf of Edra S.p.A., with unconditional support/sponsorship of by Gilead Sciences S.r.l. The Expert Panel involved in the voting phase of the Delphi process included the following specialists: Catia Angiolini (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Careggi, Firenze), Alessandra Beano (A.O.U. Città della Salute, Torino), Giulia Bianchi (IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milano), Andrea Botticelli (Università Sapienza di Roma, Roma), Roberta Caputo (IRCCS Fondazione G. Pascale, Napoli), Saverio Cinieri (Ospedale Perrino, Brindisi), Luigi Coltelli (Ospedale di Livorno, Livorno), Claudia Cortesi (Policlinico Universitario di Modena, Modena), Marco Danova (ASST di Pavia e Università LIUC di Castellanza), Carmine De Angelis (Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II), Loretta D’Onofrio (Istituti Ospedalieri di Fisioterapia IRCCS (IFO), Roma), Angela Esposito (Istituto Europeo di Oncologia (IEO), Milano), Palma Fedele (Ospedale Camberlingo, Francavilla Fontana), Ornella Garrone (Policlinico Milano, Milano), Mario Giuliano (Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II), Valeria Masiello (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma), Armando Orlandi (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma), Michela Palleschi (IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori Dino Amadori, Meldola), Francesco Pantano (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario, Campus Biomedico, Roma), Marta Piras (IRCCS Ospedale San Raffaele, Milano), Emanuela Risi (Ospedale Santo Stefano, Prato), Scafetta Roberta (Campus Bio-Medico dell’Università di Roma, Roma), Chiara Saggia (ASL Vercelli), Giuseppina Sanna (Ospedale Civile Oncologico, Alghero), Simone Scagnoli (AOU Policlinico Umberto I—Sapienza Università di Roma), Stefania Stucci (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bari), Angela Toss (Policlinico Universitario di Modena, Modena), Dario Trapani (Istituto Europeo di Oncologia (IEO), Milano), Maria Rosa Valerio (Policlinico Paolo Giaccone, Palermo).

Author Contributions

Anna Amela Valsecchi, Simona Pisegna, Massimo Di Maio, Daniele Santini: conceptualization, methodology. Massimo Di Maio, Daniele Santini: supervision. All authors: data curation, investigation, writing – review, and editing.

Funding

Financial support for the preparation of the article was provided with unconditional support/sponsorship of Gilead Sciences S.r.l.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors A.A.V., A.A., R.G., L.P., and D.S., declare no conflicts of interest; S.P.: Daichii, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Gentili, Sophos, Seagen, Novartis, Roche (speaker), Gilead, AstraZeneca (investigator); G.A.: Novartis, Lilly (personal fees), Roche (grants and personal fees), Pfizer, AstraZeneca (personal fees, and nonfinancial support), Daichi (personal fees); G.B.: AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, MSD, EISAI, Gilead, Menarini/Stemline, Exact Science, Seagen, Helsinn, Takeda (consultancy/honorarium/advisory role), Gilead (Institutional fee for research grant); L.B.: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Gilead, Lilly, Menarini, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi, SeaGen (honoraria, consultancy or advisory role), Celgene, Genomic Health, Novartis (Institutional financial interests), AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo (travel grant); G.F.C.: C.C.: AstraZeneca, Daichii Sankyo, Gilead, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Seagen (Consulting/Advisory role/speaker); A.F.: Astra Zeneca, Dompè Biotech, Eisai, Exact Science, Gilead, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sophos, Seagen; R.D.: Roche, Ipsen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Gilead, Lilly, Gilead, EUSA Pharma (scientific advisory board, consulting relationship), Ipsen, Sanofi Genzyme (travel, accommodation, expenses); A.F.: M.D.M.: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, Merck, Takeda, Viatris, Ipsen, Astellas (consultancy or participation to advisory boards).

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Author notes

Massimo Di Maio and Daniele Santini contributed equally to this work.