-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Heidi Ko, Melissa Yan, Rohan Gupta, Kayla Kebbel, Abhishek Maiti, Juhee Song, Joseph Nates, Michael J. Overman, Predictors of Survival in Patients with Advanced Gastrointestinal Malignancies Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit, The Oncologist, Volume 24, Issue 4, April 2019, Pages 483–490, https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0328

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patients with cancer have a high use of health care utilization at the end of life, which can frequently involve admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU). We sought to evaluate the predictors for outcome in patients with gastrointestinal (GI) cancer admitted to the ICU for nonsurgical conditions.

The primary objective was to determine the predictors of hospital mortality. Secondary objectives included investigating the predictors of ICU mortality and hospital overall survival (OS). All patients with GI cancer admitted to the ICU at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between November 2012 and February 2015 were retrospectively analyzed. Cancer characteristics, treatment characteristics, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were analyzed for their effects on survival.

The characteristics of the 200 patients were as follows: 64.5% male, mean age of 60 years, median SOFA score of 6.7, and tumor types of intestinal (37.5%), hepatobiliary/pancreatic (36%), and gastroesophageal (24%). The hospital mortality was 41%, and overall 6‐month mortality was 75%. In multivariate analysis, high admission SOFA score > 5, poor tumor differentiation, and duration of metastatic disease ≤7 months were associated with increased hospital mortality. For OS, high admission SOFA score > 5, poor tumor differentiation, and patients who were not on active chemotherapy because of poor performance had worse outcome. In multivariate analysis, SOFA score remained significant for OS even after excluding patients who died in the ICU.

For patients with metastatic GI cancer admitted to the ICU, SOFA score was predictive for both acute and long‐term survival. A patient's chemotherapy treatment status was not predictive for hospital mortality but was for OS. The SOFA score should be utilized in all patients with GI cancer upon ICU admission for prognostication.

Patients with cancer have a high use of health care utilization at the end of life, which can frequently involve admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU). Although there have been substantial increases in duration of survival for patients with advanced metastatic cancer, their mortality after an ICU admission remains high. GI malignancy is considered one of the top three lethal cancers estimated in 2017. Survival of critically ill patients with advanced GI cancer should be evaluated to help guide treatment planning.

Abstract

摘要

背景?癌症患者在临终时使用卫生保健服务的频率较高?这可能涉及频繁地入住重症监护室 (ICU)?我们试图评估因非手术病症入住 ICU 的胃肠 (GI) 癌患者的预后预测因子?

患者和方法?主要目标为确定医院死亡率的预测因子?次要目标包括调查 ICU 死亡率和医院总生存期(OS)的预测因子?对在 2012 年 11 月至 2015 年 2 月期间入住德州大学安德森癌症中心 (University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) ICU 的所有GI癌患者进行回顾性分析?对癌症特征?治疗特征和序贯器官衰竭估计 (SOFA) 评分进行分析?以了解它们对生存期的影响?

结果?200 名患者的特征如下:64.5% 为男性?平均年龄为 60 岁?中位 SOFA 评分为 6.7?肿瘤类型为肠道肿瘤 (37.5%)?肝胆/胰腺肿瘤 (36%) 和胃食管肿瘤 (24%)?医院死亡率为 41%?总体 6 个月死亡率为 75%?在多变量分析中?入院高 SOFA 评分 > 5?肿瘤分化差以及转移性疾病持续时间 ≤7 个月均与医院死亡率升高相关?对于 OS?入院高 SOFA 评分 > 5?肿瘤分化差以及因体能状态差而未能进行积极化疗的患者具有较差的预后?在多变量分析中?即使排除在 ICU 中死亡的患者之后?SOFA 评分对 OS 而言仍然十分重要?

结论?对于入住 ICU 的转移性 GI 癌患者?SOFA 评分可以预测急性和长期存活?患者的化疗状态不能预测医院死亡率?但可以预测 OS?在入住 ICU 时?应对所有 GI 癌患者采用 SOFA 评分?以便进行预后预测?

实践意义:癌症患者在临终时使用卫生保健服务的频率较高?这可能涉及频繁地入住重症监护室 (ICU)?尽管晚期转移癌患者的生存期已大幅提高?但是?他们在入住 ICU 之后的死亡率仍然很高?据 2017 年预测?GI 恶性肿瘤被人们看作是三大致命性癌症之一?为了帮助指导治疗规划?应对生命垂危的晚期 GI 癌患者的生存期进行评估?

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) tract malignancies were among the top three most lethal cancers estimated in 2017 [1]. Therefore, patients with GI cancer may have a high use of health care utilization at the end of life, which can frequently involve admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU). Although there have been substantial increases in duration of survival for patients with advanced metastatic cancer, their mortality after an ICU admission remains higher than those of critically ill patients without cancer [2–5]. Our group has previously shown in a large observational cohort over 20 years that among 387,306 adult hospitalized patients, the ICU utilization rate was 12.9%. The overall hospital mortality rate was 3.6%: 16.2% among patients with an ICU stay and 1.8% among non‐ICU patients [6]. Other studies have shown a wide range of prognostic factors for short‐term ICU mortality in patients with cancer, including cancer characteristics, patients' underlying disease morbidities, and acute illness score [7,8]. Although GI malignancy is considered one of the top three lethal cancers, the survival of the specific group of critically ill patients with GI cancer has not been well studied.

Over the last few decades, several ICU scoring systems, including MODS, APACHE II, SAPS II, and SOFA, have been used as objective ways to describe mild to severe organ dysfunction and help guide treatment decisions [9–12]. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was initially developed to sequentially assess the severity of organ dysfunction in patients who were critically ill from sepsis [13]. The utilization of SOFA score in patients with cancer was validated in two large studies of 3,747 and 6,645 critically ill patients with cancer. Both studies demonstrated that SOFA score had good discrimination in predicting mortality in critically ill patients with cancer [14,15]. In this study we have used SOFA score as a predictor of mortality in critically ill patients with GI malignancy.

Patients, families, and physicians are often faced with the challenge of making informed decisions at the end of life care when these patients are admitted to the ICU. A better understanding of clinical factors that are associated with short‐ and long‐term survival after an ICU admission can help formulate appropriate treatment decisions. We sought to evaluate the predictors for outcome in patients with GI cancer admitted to the ICU for nonsurgical conditions. The primary objective of our study was to determine the predictors of survival for hospital mortality in critically ill patients with GI cancer.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

A total of 447 patients with GI cancer, who had been admitted to the ICU at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MD Anderson) between November 1, 2012, and February 28, 2015, were retrospectively reviewed. Eligibility was restricted to patients with metastatic gastrointestinal cancers and to the patient's first ICU admission during this time period. We also excluded patients who were admitted to the ICU for perioperative care. A total of 247 patients were excluded because of the following reasons: 80 had perioperative admissions, 62 had non‐GI malignancies, 98 had no metastatic disease, and 7 had two concurrent cancers. A total of 200 patients met these eligibility criteria and were analyzed. This study was conducted under the approval of the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board, and because of the retrospective nature of these analyses, a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Study Design

The primary objective of this retrospective study was to determine the predictors of survival for hospital mortality. Secondary objectives were to determine the predictors of survival for ICU mortality and overall survival (OS). ICU, hospital, and overall mortality were measured from the time of initial ICU admission to the last date of contact or death. We defined hospital mortality as short‐term or acute survival and OS as long‐term survival. Median follow‐up time was calculated from the date of ICU admission.

Patient characteristics including cancer characteristics (tumor type, grade of tumor, duration from metastatic disease to ICU admission) and treatment characteristics (number of lines of chemotherapy and active chemotherapy status) were studied for their effects on survival endpoints. Standard ICU admission criteria that align with ICU admission guidelines according to the Society of Critical Care Medicine were used [16]. Patients' various clinical characteristics present at the time of ICU admission were also recorded to assess their impact on survival endpoints. Patients' active chemotherapy status was defined as whether patients were currently on treatment or off treatment because of reasons such as completion of treatment or treatment not offered because of poor functional status. Poor functional status was obtained from physician notes stating that a patient was not initiated on therapy because of their poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status. The severity of the illness, as measured by SOFA scores, was calculated prospectively for all patients admitted to the ICU during this time period. The SOFA score defines severity based on six organ systems, including cardiovascular, hepatic, coagulation, renal, and neurological systems, with scores ranging from 0 to 24, and patient's code status.

Statistical Analysis

Patients' characteristics were tabulated and compared between groups by using the chi‐squared test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate for categorical variables, and by a two‐sample t test or a nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to examine the relationship between clinical characteristics and hospital mortality and ICU mortality. Variables that had significant univariate p values were included in the multivariate model and insignificant variables were eliminated by backward selection. The Hosmer‐Lemeshow test was used to check the final model fit. The Kaplan‐Meier product limit method was used to estimate survival probabilities. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models utilizing backward elimination were fitted to determine the association between clinical characteristics and overall survival. Proportional hazards assumption was checked by visually inspecting the Kaplan‐Meier plot. However, because of the unique nature of Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) status, this variable was not included in multivariate models. All tests were two‐sided, and p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 200 patients with metastatic GI cancer admitted to the ICU at MD Anderson for nonsurgical reasons were analyzed. The study population was 64.5% male with mean age of 60 years (range, 22–86 years). The most common tumor types were primary intestinal (37.5%), hepatobiliary/pancreatic (36%), and gastroesophageal (24%; Table 1). Median follow‐up among all patients was 7.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.8–9.4 months) and at the time of this analysis, 142 patients (71%) had died. The ICU mortality rate was 26% (95% CI, 20%–32%), and hospital mortality rate was 41% (95% CI, 34%–48%). Overall mortality rate was 71% at last follow‐up.

Patient and clinical characteristics for all patients and by hospital survival status

Intestinal tumor type included 65 colorectal and 10 small bowel.

Hepatobiliary tumor type included 41 pancreas, 14 hepatocellular, and 17 biliary.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Patient and clinical characteristics for all patients and by hospital survival status

Intestinal tumor type included 65 colorectal and 10 small bowel.

Hepatobiliary tumor type included 41 pancreas, 14 hepatocellular, and 17 biliary.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Hospital Mortality

In the univariate analysis for hospital mortality, patients with a shorter duration of metastatic disease, poor tumor grade, and higher admission SOFA score (6–10 and > 10 compared with ≤5) were significantly associated with increased risk of hospital death (Table 2). Similar results were noted for ICU mortality (supplemental online Table 1). Patients with a code status of DNR had a high hospital mortality rate of 66% (21 of 32 patients), and as this status was frequently determined immediately prior to ICU admission because of the acute illness, this factor was not utilized in multivariate logistic regression model.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model for hospital mortality

Duration of disease, admission SOFA, grade, tumor, and chemo stop reason were initially included in a multivariate logistic regression model and reduced by backward elimination.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model for hospital mortality

Duration of disease, admission SOFA, grade, tumor, and chemo stop reason were initially included in a multivariate logistic regression model and reduced by backward elimination.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Multivariate logistic regression model for hospital mortality showed that admission SOFA score 6–10 (odds ratio [OR], 2.3; 95% CI, 1.0–5.3; p = .04) and > 10 (OR, 6.6; 95% CI, 2.3–19.1; p = .0004), shorter duration of metastatic disease (≤7 months; OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.1–5.0; p = .03), and poorly differentiated tumor (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.2–5.8; p = .01) were associated with increased hospital mortality (Table 2). Similar results were noted for ICU mortality as shown in supplemental online Table 1. Overall, the data suggest that admission SOFA score was a significant predictor of acute short‐term survival. The mean SOFA score on admission were 5.5 ± 3.5 points in hospital survivors and 9.6 ± 5.1 points in nonsurvivors.

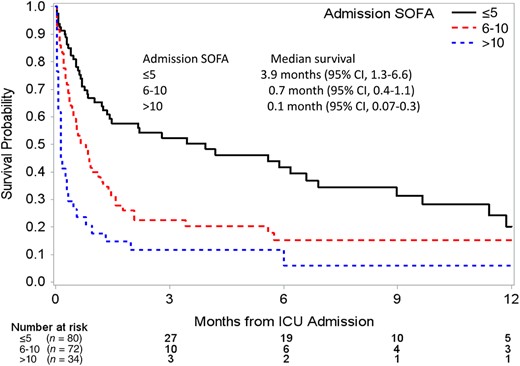

OS from ICU Admission

The 1‐, 2‐, and 6‐month OS rates were 46%, 35%, and 25% respectively (supplemental online Table 2). The Kaplan–Meier curves for OS stratified by SOFA score are shown in Figure 1. Similar to hospital mortality, both poor tumor differentiation (hazard ratio [HR] 2.5, 95% CI 1.6–3.8, p < .0001) and admission SOFA score of 6–10 (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–2.7; p = .01) and SOFA score of >10 (HR, 4.0; 95% CI, 2.3–6.8; p < .0001) were statistically significant in multivariate analyses (Table 3). In addition, patients' chemotherapy status was statistically significant in both univariate and multivariate analyses. Patients who were not on active chemotherapy because of poor performance status prior to ICU admission demonstrated a worse OS (HR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.3–4.6; p = .008). Patients with admission SOFA score 6–10 and > 10 had 6‐month OS estimates of 15% and 12%, respectively, whereas those with SOFA score ≤ 5 had 37% 6‐month OS. Interestingly, after excluding the 52 ICU deaths, multivariate analysis in the remaining 148 patients demonstrated SOFA score in addition to tumor grade to be the only two statistically significant factors (supplemental online Table 3). This further supports the prognostic relevance of initial admission SOFA score for both acute and long‐term prognostication.

Kaplain‐Meier survival estimates by admission SOFA score group.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Duration of disease, admission SOFA, grade, tumor, and chemo stop reason were initially included in a multivariate cox regression model and reduced by backward elimination.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Duration of disease, admission SOFA, grade, tumor, and chemo stop reason were initially included in a multivariate cox regression model and reduced by backward elimination.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Discussion

This study identified factors that predict both acute and long‐term survival in patients with advanced GI cancer admitted to the ICU. Both aggressive cancer characteristics, such as poor histological grade and short duration of metastatic disease, in addition to the severity of the acute illness upon ICU admission defined by SOFA, were significantly associated with both worse acute and long‐term survival. Interestingly, the cessation of systemic chemotherapy treatment because of poor performance status was not significant for short‐term outcome but was for overall survival. High admission SOFA score was the most predictive factor for mortality for all endpoints: ICU, hospital, and overall.

Oncologists, patients, and family members are often confronted with a fundamental question with regard to ICU care: will ICU admission prolong life with an acceptable quality of life, or will it extend a potentially distressful process of dying? Such decision making must consider acute illness, oncological long‐term prognosis, and anticipated quality of life [17]. At present there is a lack of objective data to help guide this decision‐making process. This study attempts to identify factors that predict both acute and long‐term survival in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer to help provide objective data with regard to expected ICU outcomes for patients, families, and treating physicians.

A recent study of 28 patients with previously treated metastatic GI cancers who were admitted to the ICU for sequelae of progressive clinical deterioration reported that there were ten deaths in the ICU, three additional patients died in the hospital after ICU discharge, and the median survival of the 15 patients who were discharged from the hospital was only 2.2 months [18]. In the current study we evaluated outcomes of a larger cohort of 200 patients with metastatic GI malignancies who were admitted to the ICU.

Studies have shown that aggressive measures with mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and renal replacement therapy correlate with increase mortality. In addition, sepsis is one of the major causes of ICU admission in patients with cancer, which is similar to our study population in which 35% of patients presented with sepsis [19–22]. In our study, we found that there were 68 patients who required vasopressors, 64 patients with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, 12 patients with renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy. There were 82 (41%) hospital deaths and 52 (26%) ICU deaths. The large observational cohort study by Wallace et al. of >50,000 patients with cancer in the ICU demonstrated that patients with hematological cancers had a high mortality rate of 43% compared with patients with solid tumors with a rate of 25% [6]. In this study, the ICU mortality rate was 19% and the hospital mortality rate was 27%. Our study's higher mortality rate could relate to our focus on patients with a nonsurgical reason for hospital admission. In addition, our study demonstrates that aggressive cancer characteristics, such as tumor grade and duration of metastatic disease, correlate with acute hospital survival in contrast to prior studies in which acute illness, specifically scores such as APACHE or SOFA, was the sole predictor for hospital survival [2,3,23].

Prior studies have reported that the major predictors of long‐term prognosis in patients with cancer admitted to the ICU were progression of cancer after hospital discharge and a prolonged need for mechanical ventilation during ICU admission [24–26]. A prospective multicenter study of 449 patients with lung cancer admitted to 22 ICUs in Europe showed similar findings of organ dysfunction severity, poor performance status, and recurrent or progressive cancer as significant predictors of mortality [27]. We found that high SOFA score 6–10 and > 10 again was associated with worse OS. Even after excluding ICU deaths, we found that SOFA score > 5 remained statistically significant for OS, suggesting that it is still prognostic for overall long‐term outcome. In addition, poorly differentiated tumors and patients who are not on active chemotherapy prior to ICU admission because of poor performance status were associated with worse OS. Poorly differentiated tumors such as signet ring colorectal adenocarcinomas have been shown to be associated with poorer survival outcomes [28]. In addition, ECOG performance status is a well‐known prognostic factor with multiple prior studies demonstrating worse survival in multivariate analyses in patients with ECOG performance status of 3–4 [3,29].

One of the more interesting findings from this study is that the outpatient systemic treatment status prior to ICU admission, as assessed by the patient's treating medical oncologist, did not impact acute mortality. In many of these cases, discussions regarding supportive care focus and hospice care were documented. Despite the oncological concern over ability to tolerate aggressive chemotherapy, the primary determinant of acute survival was determined not by this later time point in a patient's disease course but rather by the severity of the acute illness. Such data demonstrate the critical importance of accurate assessment of a patient's acute illness severity. Therefore, early communication between the oncology and intensive care team regarding the severity of the SOFA score could potentially be one of the objective tools for the physicians to triage the ICU patient appropriately.

The current study has several limitations. Although most reasons for admission to the ICU are standard nowadays, there may be certain subjective aspects of decision making that vary from one institution to another; therefore, a single‐institution retrospective study may not be fully applicable to all intensive care units. Although SOFA was prospectively calculated on all patients on hospital admission, this was a retrospective study with potential for both selection and interpretation bias. In addition, this study represents a selective subset of patients with cancer admitted to the ICU. This selective subset was by design, as limited data sets currently exist to help prognosticate for medical oncologists and intensivists for patients with incurable metastatic cancer. Moreover, as this was retrospective in nature, assessments of patients' quality of life were not possible. Also, the generalizability of our multivariate models has not been examined with an independent data set that was not used to develop the models. Therefore, the true predictive validity of each model should be investigated in future studies.

Conclusion

Our study identified the predictors of acute and long‐term survival in critically ill patients with GI cancer admitted to the ICU. The SOFA score was a significant predictive factor for ICU mortality, hospital mortality, and OS in this patient population. It should be utilized in all patients with GI cancer upon ICU admission to improve both acute and longer‐term prognostication. Patients with high grade tumors or short duration of metastatic disease may not have good short‐term outcomes in the ICU. Interestingly, patients who were not eligible for aggressive systemic chemotherapy did not have worse admission mortality than other patients. However, as expected, this was a predictive factor for longer‐term OS. Understanding the predictors of short‐ and long‐term survival is important in treatment planning, especially terminal care management. Based on the retrospective data, which need further validation, we can recommend that a judicious approach should be taken in patients with predictors of poor survival before subjecting them to aggressive treatment.

Acknowledgments

We did not have any financial support. We thank the critical care team for providing the initial data and SOFA scores. We thank Dr. Juhee Song for the statistical analysis, which was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI grant P30 CA016672). Heidi Ko is currently at the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, USA. Melissa Yan is currently at the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Indiana University Simon Cancer Center, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Heidi Ko, Melissa Yan, Rohan Gupta, Kayla Kebbel, Abhishek Maiti, Juhee Song, Joseph Nates, Michael J. Overman

Collection and/or assembly of data: Heidi Ko, Melissa Yan, Rohan Gupta, Kayla Kebbel, Abhishek Maiti

Data analysis and interpretation: Heidi Ko, Melissa Yan, Juhee Song

Manuscript writing: Heidi Ko, Melissa Yan, Juhee Song

Final approval of manuscript: Heidi Ko, Melissa Yan, Rohan Gupta, Kayla Kebbel, Abhishek Maiti, Juhee Song, Joseph Nates, Michael J. Overman

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

Author notes

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

Editor's Note: See the accompanying commentary, “Numbers Have Life: A Commentary on “Predictors of Survival in Patients with Advanced Gastrointestinal Malignancies Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit”,” by Jennifer G. Le‐Rademacher and Aminah Jatoi on page 433 of this issue.