-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shalini Dalal, Eduardo Bruera, End‐of‐Life Care Matters: Palliative Cancer Care Results in Better Care and Lower Costs, The Oncologist, Volume 22, Issue 4, April 2017, Pages 361–368, https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0277

Close - Share Icon Share

Introduction

There are clearly two problems facing people at the end of life. The first is that quality care does not reach enough people, and the second is that the rising costs of health care over preceding decades have imposed a substantial financial burden on patients, families, and the health care system. These two major problems may be mitigated with earlier and increased palliative care (PC) involvement, with mounting evidence confirming the benefits of PC on both costs and quality of care . This is a significant realization, as the primary goal of any medical intervention is never cost reduction, and reducing costs also reduces the quality and intensity of services being delivered. For example, an orthopedics practice attempting to reduce costs by delaying hip replacement surgery would inevitably create more pain and disability for the patient. Such attempts at cost reductions that disregard outcomes are potentially dangerous and unacceptable. PC is unique in that sense, for by increasing PC interventions, the primary clinical effects—decrease in symptom burden, increased communication between teams, and better alignment of treatment with patient’s goals—occur in conjunction with cessation of ineffective or unwanted treatments and decreased hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) services, thereby achieving the secondary and unintended outcome of cost reduction.

Despite much evidence, end‐of‐life care and planning continues to be ignored in most contexts. The politics of the matter are especially controversial. Prior to the enactment of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) [9], a proposal for providing Medicare coverage for end‐of‐life counseling became highly charged, as some opponents misrepresented such planning to be synonymous with physician “death panels,” deciding who will live or die. The myth was quickly discredited but not before the final ACA bill had been stripped of any reference to end‐of‐life care. Not until 2016 did Medicare fix it, and voluntary end‐of‐life counseling became reimbursable. This correction was most appropriate because the Institute of Medicine (IOM) identifies patient‐centeredness along with the delivery of safe and effective treatments as crucial aspects of quality health care, including at the end of life [10].

In recent years, value‐based health care performance measures have been proposed, with rising recognition that care must deliver effective patient‐based outcomes through patient‐centeredness, quality, and cost containment. Michael Porter has defined value in health care in terms of patient health outcomes being achieved relative to the costs of care, although, importantly, such value is only created when health outcomes are never compromised [11]. Focusing on value, not just costs, avoids the pitfall of choosing expensive or obligatory treatments and allows for the consideration of effective personalized treatments that may become best practice [11]. In terminally ill cancer patients, effective outcomes inevitably vary with the stage of illness and functionality, necessitating individualized approaches that respect the patient’s goals, even ones not necessarily related to increasing survival. PC has emerged as a valuable intervention in recent years. To measure its value in oncological care, it is important to discuss the most common problems and challenges facing cancer patients, the effectiveness of PC interventions in addressing these, and the impact PC has on reducing health care costs. This article reviews the current state of end‐of‐life care, analyzes the clinical and financial impact of PC, and proposes areas of future research and development.

Suffering at the End of Life

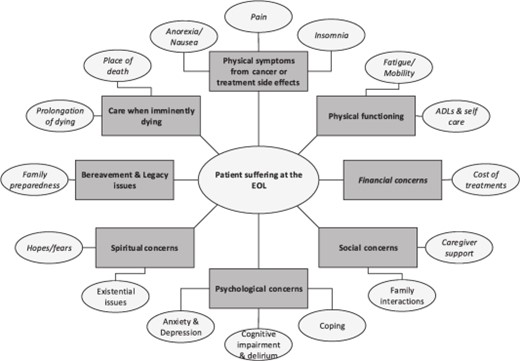

Suffering in terminally ill cancer patients can stem from multiple problems, including uncontrolled symptoms, inadequate practical and emotional support, unexpected financial burden, lack of communication, disregard for patient/family goals, setting preferences, or even prolongation of the dying process (Fig. 1).

Multidimensional causes of patient suffering at the EOL.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; EOL, end of life.

Symptom Burden at the End of Life

Symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, and depression are among the most prevalent and distressing aspects of the end‐of‐life experience for patients and families . The daily struggles and suffering experienced by dying Americans was highlighted in the IOM’s 1997 report, “Approaching death: Improving care at the end of life.” It described many shortcomings as well, including the lack of trained personnel and quality performance measures, and stressed the urgency for improvements [15]. Several recommendations have been incorporated into end‐of‐life care guidelines and quality metrics, along with the expansion of PC programs in hospitals [16] and hospices in community settings [17]. The National Quality Forum and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have jointly endorsed a set of overly aggressive performance metrics denoting poor‐quality care , which are now integrated into ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative performance measures (Table 1) [20]. Despite such progress, recent studies on symptom burden and the quality of care at the end of life suggest worsening outcomes over time . In more recent reports , the IOM has highlighted three main areas for improvement: (a) communication (such as about disease prognosis, benefits and burdens of treatments, initiation of PC, the costs of care, and psychological support); (b) tailoring of end‐of‐life care to patient’s needs, values, and preferences; and (c) the provision of coordinated team‐based care.

Selected Quality Oncology Practice Initiative’s end‐of‐life quality outcome performance measures

| Description . | Measure . |

|---|---|

| Pain | Plan for pain Pain assessed before death Pain intensity quantified before death Pain assessed appropriately before death |

| Dyspnea | Dyspnea assessed before death Dyspnea addressed before death Dyspnea addressed appropriately before death |

| Hospice | Hospice or palliative care used Enrolled in hospice Hospice within 3 days of death |

| Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy administered within the last 2 weeks of life |

| Emergency room visit | Any emergency room visit within the last month of life Two or more emergency room visits within the last month of life |

| Hospital admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life Two or more hospital admission within the last month of life More than 14 days of hospitalization within the last month of life Hospital death |

| ICU admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life ICU death |

| Description . | Measure . |

|---|---|

| Pain | Plan for pain Pain assessed before death Pain intensity quantified before death Pain assessed appropriately before death |

| Dyspnea | Dyspnea assessed before death Dyspnea addressed before death Dyspnea addressed appropriately before death |

| Hospice | Hospice or palliative care used Enrolled in hospice Hospice within 3 days of death |

| Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy administered within the last 2 weeks of life |

| Emergency room visit | Any emergency room visit within the last month of life Two or more emergency room visits within the last month of life |

| Hospital admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life Two or more hospital admission within the last month of life More than 14 days of hospitalization within the last month of life Hospital death |

| ICU admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life ICU death |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit.

Selected Quality Oncology Practice Initiative’s end‐of‐life quality outcome performance measures

| Description . | Measure . |

|---|---|

| Pain | Plan for pain Pain assessed before death Pain intensity quantified before death Pain assessed appropriately before death |

| Dyspnea | Dyspnea assessed before death Dyspnea addressed before death Dyspnea addressed appropriately before death |

| Hospice | Hospice or palliative care used Enrolled in hospice Hospice within 3 days of death |

| Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy administered within the last 2 weeks of life |

| Emergency room visit | Any emergency room visit within the last month of life Two or more emergency room visits within the last month of life |

| Hospital admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life Two or more hospital admission within the last month of life More than 14 days of hospitalization within the last month of life Hospital death |

| ICU admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life ICU death |

| Description . | Measure . |

|---|---|

| Pain | Plan for pain Pain assessed before death Pain intensity quantified before death Pain assessed appropriately before death |

| Dyspnea | Dyspnea assessed before death Dyspnea addressed before death Dyspnea addressed appropriately before death |

| Hospice | Hospice or palliative care used Enrolled in hospice Hospice within 3 days of death |

| Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy administered within the last 2 weeks of life |

| Emergency room visit | Any emergency room visit within the last month of life Two or more emergency room visits within the last month of life |

| Hospital admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life Two or more hospital admission within the last month of life More than 14 days of hospitalization within the last month of life Hospital death |

| ICU admission | Any hospital admission within the last month of life ICU death |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit.

End‐of‐Life Care Is Frequently at Odds with Patient/Family Preferences

When informed about poor prognosis, a majority of cancer patients and their families prefer comfort‐ over cure‐focused care and prefer to die at home rather than in the hospital setting . Yet in reality, the care is increasingly aggressive and complex, which is not only at odds with patient preferences but also associated with poorer clinical outcomes and quality of life (QoL) . Some studies showed an encouraging trend of a lower proportion of cancer patients dying in acute care hospitals and a higher number of hospice enrollments in the last month of life, but this was dampened by findings of higher rate of ICU and hospital utilization in the last months of life and higher proportion of hospice referrals in the last 3 days of life, respectively . The studies highlight the importance of eliciting individual preferences via better communication, as there is frequent disagreement whenever physicians assume what their patients would prefer . Among cancer patients, preferences for making such decisions vary, ranging from active to passive, with shared decision‐making being the most preferred .

Bereaved Family Outcomes

When a patient’s end‐of‐life preferences are not met, family/caregivers experience regret and worsening QoL and are at a higher risk of developing a major depressive disorder [40]. Family members perceive end‐of‐life care to be worse in the context of hospital deaths, ICU admission in the last month of life, or if hospice enrollment occurred late or not at all [41]. Counseling to families/caregivers is still not routine, even for patients with advanced cancers, but is an important component of PC. The ENABLE III trial compared the timing of PC tele‐health caregiver counseling support when given early (≤60 days of advanced‐cancer diagnosis) versus delayed (≥12 weeks of diagnosis) and found that prior to death, caregivers in the early group had lower depressions scores 3 months after intervention [42]. However, there was no differences between groups on depression or complicated‐grief scores at 8–12 weeks after death [43]. To our knowledge, no study has compared the impact of counseling by PC versus the standard of care on bereaved family/caregiver outcomes following a cancer death

Financial Hardship to Patients and Families

The financial burden to patients/families as a result of medical care is rapidly rising, with one in three Americans experiencing hardships [44]. The burden is far greater for cancer patients, who pay more out of pocket than those with other chronic illnesses, even when privately insured or Medicare beneficiaries . In a recent study, 10% of Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental insurance were found to spend over 60% of their annual income on out‐of‐pocket expenses following cancer diagnosis, with inpatient hospitalizations accounting for 46% of expenses [48]. Similar high costs occurred at the end of life, and inpatient hospitalizations were the primary contributor [48]. In a study of advanced cancer patients referred to PC services, financial distress was found to be highly prevalent in both the general public and the comprehensive cancer hospitals, but the intensity was twice as severe at the public hospital [49]. Approximately 30% of patients rated financial distress to be more severe than physical, family, and emotional distress [49]. More than four out of five oncologists report that concerns regarding out‐of‐pocket spending influence their treatment recommendations, although fewer than half routinely discuss financial issues with patients [50].

PC Improves Quality of Care

The concept of providing patient‐ and family‐centric care in the context of terminal illness when high symptom burden and existential queries are faced by those with inadequate coping skills is not foreign to PC. Far from it, this skill set is precisely why the IOM recommends all people with serious advanced illnesses have access to skilled PC [51]. In an ideal model, PC would be incorporated early, preferably at the time of diagnosis of advanced illness, thereby optimizing QoL by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering, providing clarity on medical decisions, and providing a platform for patients, families, and all medical providers to communicate about patient care/goals. PC interventions incorporated over the course of illness, rather than towards the end, align more closely to the needs and preferences of terminally ill patients and families.

Various prospective studies have demonstrated timely integration of PC with oncologic care to be associated with significant improvements in QoL , symptoms , and satisfaction with care [4].The 2010 randomized controlled trial (RCT) of newly diagnosed metastatic lung cancer patients also demonstrated a survival advantage in the concurrent PC and oncology arm despite less aggressive care (chemotherapy ≤14 days before death and very late or no hospice referral) [7]. Even in the curative setting, such as among patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), a recently published RCT (n = 160) [52] demonstrated lower reductions in QoL at 2 weeks post‐HSCT in the concurrent inpatient PC and standard transplant care arms. At 3 months post HSCT, the PC‐arm patients had higher QOL and less depression but did not differ from the standard arm with respect to overall symptom burden. The same group of investigators also presented an abstract at ASCO 2016 on another RCT [53] conducted in patients newly diagnosed with advanced lung or gastrointestinal malignancies and found higher QOL, lower depression scores (at 24 weeks), and higher frequency of EOL discussions in the PC arm, as compared with the oncology‐alone arm.

Several studies suggest that even after one visit with PC in the outpatient or inpatient setting, there are improvements in physical and psychological symptoms, QoL, as well as patient satisfaction with care and provider communication . In the ICU, PC consultations are associated with improved pain and other symptoms, facilitation of discussion on advanced care planning, and lower use of nonbeneficial life‐prolonging treatments . Studies of patients hospitalized at specialized PC units also demonstrate decreased symptom burden and improvements in care beyond those achieved with the PC consultation service .

Hospice services delivered at home or at nursing facilities have been associated with improved quality outcomes for terminally ill patients and their families, such as higher patient QoL and satisfaction with care , along with lowered risks of bereaved caregivers developing a major depressive disorder [70]. In addition, in one report that looked at survival outcomes, patients enrolled in hospice services had higher survival [71].

PC Reduces Costs

Improving patient/family outcomes while simultaneously decreasing costs makes PC a high‐value intervention, driving the rapid expansion of hospital‐based PC programs all over the country [16]. Across hospital types, PC involvement in the care of seriously ill‐patients has been associated with lower hospital costs directly in dollars and/or implied by lower hospital, ICU, or Emergency Care (EC) utilization. (Table 2) . The magnitude of hospital cost savings with PC involvement ranges from 9%–32% . These savings are higher when PC is involved earlier (≤2 days of admission) [87], when patients have higher comorbidities [81], and for patients who die during the hospitalization as compared with those discharged alive . In the one RCT that examined health care costs and utilization post hospital discharge following PC consultation, patients in the PC arm had fewer ICU admissions on readmission to the hospital and an estimated 32% reduction in total health care costs over 6 months post discharge [59]. In the outpatient setting, a recent secondary analysis [3] of the Temel study in lung cancer patients [7] found early PC to be not associated with higher overall health care expenses and a statistical trend towards lower mean total costs per day.

Studies demonstrating cost savings associated with PC consultations in the inpatient setting

| Author (Year) . | Study design/objective . | Findings: PC versus SC . |

|---|---|---|

| Greer (2016) [3] | Randomized controlled, single center; secondary analysis. Advanced lung cancer; n = 151 | As compared with SC, early PC was not associated with higher overall medical care expenses. There was a statistical trend for PC patients towards lower mean total cost per day ($117; p = .13). In the last 30 days of life, PC patients had lower chemotherapy expenses (mean difference = $757; p = .03) and higher hospice care costs in last 30 days (mean difference = $1,053; p = .07). Other costs (emergency visits, hospitalizations) not significant over study period. |

| May (2016) [81] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 906 | PC consult ≤2 days of admission associated with lower costs. Cost savings were proportional to patient comorbidity scores: 22% lower for scores of 2–3 and 32% lower for ≥4. |

| May (2015) [87] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 969 | PC consultation ≤2 days and ≤6 days of admission associated with cost reductions of 24% and 14%, respectively. |

| Whitford (2014) [79] | Retrospective case–control, single‐center. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 5,908 | Among patients discharged alive, overall hospitalization costs were lower, and higher numbers (31% versus 1%) were discharged to hospice care. Among patients who died in hospital, costs of PC patients were significantly lower. |

| Morrison (2011) [76] | Retrospective case control, multi‐site. Medicaid patients with advanced illness | Hospital cost savings of $4,098 and $7,563 for patients who were discharged alive and when death happened during hospitalization, respectively. |

| Penrod (2010) [73] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced illness; n = 3,321 | PC patients were approx. 44% less likely to be admitted to ICU, and daily total direct hospital costs were lower than SC patients. |

| Zhang (2009) [88] | Prospective observational, single center. Advanced cancer; n = 603 | Patients who had EOL conversations were less likely to undergo aggressive care (e.g., resuscitation/ventilation, ICU) and more likely to receive hospice care with longer LOS. Cost of care was about 36% lower in the final week of life. Higher costs associated with worse quality of death. |

| Gade (2008) [59] | Randomized controlled, multi‐center. Advanced illness; n = 517 | Six months post hospital discharge, PC patients had fewer ICU admissions on readmission, longer hospice LO,S and about 32% reduction in total health care. |

| Morrison (2008) [75] | Retrospective case controlled, multi‐site. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 4,402 | As compared with SC, PC patients who were discharged alive had significant savings in daily and overall admission costs, including lower laboratory and ICU costs. For PC patients who died in hospital, the net savings in daily and overall admission costs were higher than for patients who were discharged. |

| Penrod (2006) [72] | Retrospective, observational, multi‐site. 40% cancer diagnosis; n = 314 | Cost analysis of hospital deaths at two Veterans Affairs hospitals demonstrated PC involvement associated with 40% less likelihood of ICU admission. |

| Elsayem (2004) [64] | Retrospective, single center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 320 | The mean daily PCU charges were 38% lower than the rest of the hospital. |

| Smith (2003) [82] | Retrospective with case control design, single center. Majority cancer diagnosis; n = 237 | Study compared period before and after PCU transfer and found daily charges and costs after transfer to be lower by 66%. For patients who died in PCU versus outside PCU, direct and total costs were lower by 59% and 57%, respectively. |

| Bruera (2000) [86] | Retrospective, multi‐center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 2,583 | Study compared the period before and after PC program implementation and demonstrated significantly lower hospital LOS, hospital mortality, and acute care facility costs after PC program implementation. |

| Author (Year) . | Study design/objective . | Findings: PC versus SC . |

|---|---|---|

| Greer (2016) [3] | Randomized controlled, single center; secondary analysis. Advanced lung cancer; n = 151 | As compared with SC, early PC was not associated with higher overall medical care expenses. There was a statistical trend for PC patients towards lower mean total cost per day ($117; p = .13). In the last 30 days of life, PC patients had lower chemotherapy expenses (mean difference = $757; p = .03) and higher hospice care costs in last 30 days (mean difference = $1,053; p = .07). Other costs (emergency visits, hospitalizations) not significant over study period. |

| May (2016) [81] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 906 | PC consult ≤2 days of admission associated with lower costs. Cost savings were proportional to patient comorbidity scores: 22% lower for scores of 2–3 and 32% lower for ≥4. |

| May (2015) [87] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 969 | PC consultation ≤2 days and ≤6 days of admission associated with cost reductions of 24% and 14%, respectively. |

| Whitford (2014) [79] | Retrospective case–control, single‐center. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 5,908 | Among patients discharged alive, overall hospitalization costs were lower, and higher numbers (31% versus 1%) were discharged to hospice care. Among patients who died in hospital, costs of PC patients were significantly lower. |

| Morrison (2011) [76] | Retrospective case control, multi‐site. Medicaid patients with advanced illness | Hospital cost savings of $4,098 and $7,563 for patients who were discharged alive and when death happened during hospitalization, respectively. |

| Penrod (2010) [73] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced illness; n = 3,321 | PC patients were approx. 44% less likely to be admitted to ICU, and daily total direct hospital costs were lower than SC patients. |

| Zhang (2009) [88] | Prospective observational, single center. Advanced cancer; n = 603 | Patients who had EOL conversations were less likely to undergo aggressive care (e.g., resuscitation/ventilation, ICU) and more likely to receive hospice care with longer LOS. Cost of care was about 36% lower in the final week of life. Higher costs associated with worse quality of death. |

| Gade (2008) [59] | Randomized controlled, multi‐center. Advanced illness; n = 517 | Six months post hospital discharge, PC patients had fewer ICU admissions on readmission, longer hospice LO,S and about 32% reduction in total health care. |

| Morrison (2008) [75] | Retrospective case controlled, multi‐site. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 4,402 | As compared with SC, PC patients who were discharged alive had significant savings in daily and overall admission costs, including lower laboratory and ICU costs. For PC patients who died in hospital, the net savings in daily and overall admission costs were higher than for patients who were discharged. |

| Penrod (2006) [72] | Retrospective, observational, multi‐site. 40% cancer diagnosis; n = 314 | Cost analysis of hospital deaths at two Veterans Affairs hospitals demonstrated PC involvement associated with 40% less likelihood of ICU admission. |

| Elsayem (2004) [64] | Retrospective, single center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 320 | The mean daily PCU charges were 38% lower than the rest of the hospital. |

| Smith (2003) [82] | Retrospective with case control design, single center. Majority cancer diagnosis; n = 237 | Study compared period before and after PCU transfer and found daily charges and costs after transfer to be lower by 66%. For patients who died in PCU versus outside PCU, direct and total costs were lower by 59% and 57%, respectively. |

| Bruera (2000) [86] | Retrospective, multi‐center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 2,583 | Study compared the period before and after PC program implementation and demonstrated significantly lower hospital LOS, hospital mortality, and acute care facility costs after PC program implementation. |

Abbreviations: EOL, end of life; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; PC, palliative care; PCU, PC unit; SC, standard care.

Studies demonstrating cost savings associated with PC consultations in the inpatient setting

| Author (Year) . | Study design/objective . | Findings: PC versus SC . |

|---|---|---|

| Greer (2016) [3] | Randomized controlled, single center; secondary analysis. Advanced lung cancer; n = 151 | As compared with SC, early PC was not associated with higher overall medical care expenses. There was a statistical trend for PC patients towards lower mean total cost per day ($117; p = .13). In the last 30 days of life, PC patients had lower chemotherapy expenses (mean difference = $757; p = .03) and higher hospice care costs in last 30 days (mean difference = $1,053; p = .07). Other costs (emergency visits, hospitalizations) not significant over study period. |

| May (2016) [81] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 906 | PC consult ≤2 days of admission associated with lower costs. Cost savings were proportional to patient comorbidity scores: 22% lower for scores of 2–3 and 32% lower for ≥4. |

| May (2015) [87] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 969 | PC consultation ≤2 days and ≤6 days of admission associated with cost reductions of 24% and 14%, respectively. |

| Whitford (2014) [79] | Retrospective case–control, single‐center. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 5,908 | Among patients discharged alive, overall hospitalization costs were lower, and higher numbers (31% versus 1%) were discharged to hospice care. Among patients who died in hospital, costs of PC patients were significantly lower. |

| Morrison (2011) [76] | Retrospective case control, multi‐site. Medicaid patients with advanced illness | Hospital cost savings of $4,098 and $7,563 for patients who were discharged alive and when death happened during hospitalization, respectively. |

| Penrod (2010) [73] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced illness; n = 3,321 | PC patients were approx. 44% less likely to be admitted to ICU, and daily total direct hospital costs were lower than SC patients. |

| Zhang (2009) [88] | Prospective observational, single center. Advanced cancer; n = 603 | Patients who had EOL conversations were less likely to undergo aggressive care (e.g., resuscitation/ventilation, ICU) and more likely to receive hospice care with longer LOS. Cost of care was about 36% lower in the final week of life. Higher costs associated with worse quality of death. |

| Gade (2008) [59] | Randomized controlled, multi‐center. Advanced illness; n = 517 | Six months post hospital discharge, PC patients had fewer ICU admissions on readmission, longer hospice LO,S and about 32% reduction in total health care. |

| Morrison (2008) [75] | Retrospective case controlled, multi‐site. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 4,402 | As compared with SC, PC patients who were discharged alive had significant savings in daily and overall admission costs, including lower laboratory and ICU costs. For PC patients who died in hospital, the net savings in daily and overall admission costs were higher than for patients who were discharged. |

| Penrod (2006) [72] | Retrospective, observational, multi‐site. 40% cancer diagnosis; n = 314 | Cost analysis of hospital deaths at two Veterans Affairs hospitals demonstrated PC involvement associated with 40% less likelihood of ICU admission. |

| Elsayem (2004) [64] | Retrospective, single center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 320 | The mean daily PCU charges were 38% lower than the rest of the hospital. |

| Smith (2003) [82] | Retrospective with case control design, single center. Majority cancer diagnosis; n = 237 | Study compared period before and after PCU transfer and found daily charges and costs after transfer to be lower by 66%. For patients who died in PCU versus outside PCU, direct and total costs were lower by 59% and 57%, respectively. |

| Bruera (2000) [86] | Retrospective, multi‐center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 2,583 | Study compared the period before and after PC program implementation and demonstrated significantly lower hospital LOS, hospital mortality, and acute care facility costs after PC program implementation. |

| Author (Year) . | Study design/objective . | Findings: PC versus SC . |

|---|---|---|

| Greer (2016) [3] | Randomized controlled, single center; secondary analysis. Advanced lung cancer; n = 151 | As compared with SC, early PC was not associated with higher overall medical care expenses. There was a statistical trend for PC patients towards lower mean total cost per day ($117; p = .13). In the last 30 days of life, PC patients had lower chemotherapy expenses (mean difference = $757; p = .03) and higher hospice care costs in last 30 days (mean difference = $1,053; p = .07). Other costs (emergency visits, hospitalizations) not significant over study period. |

| May (2016) [81] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 906 | PC consult ≤2 days of admission associated with lower costs. Cost savings were proportional to patient comorbidity scores: 22% lower for scores of 2–3 and 32% lower for ≥4. |

| May (2015) [87] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced cancer patients; n = 969 | PC consultation ≤2 days and ≤6 days of admission associated with cost reductions of 24% and 14%, respectively. |

| Whitford (2014) [79] | Retrospective case–control, single‐center. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 5,908 | Among patients discharged alive, overall hospitalization costs were lower, and higher numbers (31% versus 1%) were discharged to hospice care. Among patients who died in hospital, costs of PC patients were significantly lower. |

| Morrison (2011) [76] | Retrospective case control, multi‐site. Medicaid patients with advanced illness | Hospital cost savings of $4,098 and $7,563 for patients who were discharged alive and when death happened during hospitalization, respectively. |

| Penrod (2010) [73] | Prospective observational, multi‐site. Advanced illness; n = 3,321 | PC patients were approx. 44% less likely to be admitted to ICU, and daily total direct hospital costs were lower than SC patients. |

| Zhang (2009) [88] | Prospective observational, single center. Advanced cancer; n = 603 | Patients who had EOL conversations were less likely to undergo aggressive care (e.g., resuscitation/ventilation, ICU) and more likely to receive hospice care with longer LOS. Cost of care was about 36% lower in the final week of life. Higher costs associated with worse quality of death. |

| Gade (2008) [59] | Randomized controlled, multi‐center. Advanced illness; n = 517 | Six months post hospital discharge, PC patients had fewer ICU admissions on readmission, longer hospice LO,S and about 32% reduction in total health care. |

| Morrison (2008) [75] | Retrospective case controlled, multi‐site. Advanced illness including cancer; n = 4,402 | As compared with SC, PC patients who were discharged alive had significant savings in daily and overall admission costs, including lower laboratory and ICU costs. For PC patients who died in hospital, the net savings in daily and overall admission costs were higher than for patients who were discharged. |

| Penrod (2006) [72] | Retrospective, observational, multi‐site. 40% cancer diagnosis; n = 314 | Cost analysis of hospital deaths at two Veterans Affairs hospitals demonstrated PC involvement associated with 40% less likelihood of ICU admission. |

| Elsayem (2004) [64] | Retrospective, single center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 320 | The mean daily PCU charges were 38% lower than the rest of the hospital. |

| Smith (2003) [82] | Retrospective with case control design, single center. Majority cancer diagnosis; n = 237 | Study compared period before and after PCU transfer and found daily charges and costs after transfer to be lower by 66%. For patients who died in PCU versus outside PCU, direct and total costs were lower by 59% and 57%, respectively. |

| Bruera (2000) [86] | Retrospective, multi‐center. Advanced cancer patients; n = 2,583 | Study compared the period before and after PC program implementation and demonstrated significantly lower hospital LOS, hospital mortality, and acute care facility costs after PC program implementation. |

Abbreviations: EOL, end of life; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; PC, palliative care; PCU, PC unit; SC, standard care.

Possible reasons why PC consultation is capable of reducing costs include reduction in ICU admissions/LOS and the avoidance of or reduction in nonbeneficial expensive procedures . A case‐control study [82] demonstrated significantly lower costs of care for medically complex terminally ill patients who died in a dedicated PC unit (PCU) as compared with those who died outside the PCU and were cared for by other medical or surgical services. This study demonstrated over 50% reduction in daily charges, direct costs, and total costs of care for the PCU patients. In the community setting, hospice care was shown to decrease the use of inappropriate health system resources . There is also evidence of less intensive care with in‐home (non‐hospice) PC, as demonstrated by an RCT that found lower EC and hospital use in conjunction with higher patient satisfaction [91].

Summary and Recommendations

PC has taken much more time to be adopted by organized medicine as compared with other specialty services such as critical care or emergency medicine. One possible reason is that PC has not emerged from academic medicine but from a community hospice program in the United Kingdom. Over recent decades, though, the rapid growth of PC programs across U.S. hospitals and cancer centers testifies to the value proposition, initially based on the evidence that terminally ill patients were not receiving needed care, and more recently with research showing PC benefits in multiple domains.

There is a need for ongoing research in several areas of PC delivery and its integration with oncology. There continues to be substantial regional variability in how PC is delivered in terms of care settings, triggers for referral, team composition, and content of PC interventions. Currently, the predominant model of PC delivery in the U.S. is via inpatient consult services, without an outpatient clinic . Although inpatient PC programs provide much‐needed symptom relief to acutely hospitalized patients, such referrals occur very late in the illness trajectory . A host of oncologist‐, patient‐, or system‐related concerns and challenges continues to affect earlier PC referral [102]. Referring oncologists worry about the name of PC itself, particularly for early referral. For this reason, we had previously adopted the name “supportive care” for outpatient and inpatient consult programs and demonstrated dramatic [101] and sustained [103] increase in all referrals, including those earlier in the illness trajectory. Still, today PC is mostly driven by the inpatient consultation programs, in which an inadequate workforce is unable to provide care for large numbers of hospitalized patients and inevitably focuses on delivering care for those at the very end of life.

The future of PC integration is linked to the establishment of outpatient programs that facilitate earlier referrals, which have been shown to improve outcomes in cancer patients and are one of the major indicators of integration [104]. However, the exact timing for initiation of outpatient PC referral remains unclear. It may be possible that when patients are referred too early to PC specialists they have few or minimal symptoms, and referring them may not be beneficial to patients. In RCTs described earlier, PC referral was based on diagnosis and prognosis rather than on symptom burden, in contrast to current practice, in which oncologists refer on an as‐needed basis. Even in cancer centers with large PC programs, the adoption of PC has not been found to be uniform, with significant variations in referral pattern between oncology services, being higher for gastrointestinal and lung malignancies and lower for hematological malignancies[103].

It is unlikely that the health care system will have enough PC specialists anytime soon, so it is imperative to find an optimal balance between primary (the delivery of PC by non‐PC specialists such as oncologists and primary care clinicians) versus specialist PC. Oncology fellows report their PC education during training to be inadequate [105], with only a minority receiving mandatory rotations in PC [93], which is essential in gaining basic expertise in pain and symptom management.

The key to successful integration is to focus on collaboration and communication between oncologists and PC clinicians about roles and responsibilities between those clinicians with patients and families regarding the goals of care. Current data suggest communication gaps in eliciting individual preferences for communication . Recent preliminary studies suggest the usefulness of communication aids such as prompt sheets [106] or cards [107]. Although critical, there is very limited research on ways of improving communications between care providers themselves. To our knowledge, no studies have directly examined the role of oncologists or general practioners in the provision of primary PC, and more research is warranted.

The interdisciplinary nature of PC uniquely enables it to address the multidimensional care needs of patients. Studies incorporating interdisciplinary involvement consistently show improvements in outcomes , whereas studies utilizing uni‐disciplinary approaches show mixed findings . Currently, it is not clear how a particular PC intervention component relates to patient outcomes, and a better definition of the content of these interventions is also needed. Furthermore, although a survival benefit was associated with early PC involvement in advanced lung cancer patients [7], it is not clear which aspect of PC intervention made this possible.

Conclusion

In the past 5 decades, PC has undergone remarkable growth, evolving from a philosophy of care to a professional discipline that provides specialized care for people with serious illness. Recognizing large gaps between high‐quality end‐of‐life care and current practices across the U.S. , PC integration in health care systems has been strongly advocated to ensure access to good pain and symptom relief, practical support, and high‐quality end‐of‐life care [23]. When integrated with standard oncological care, PC improves patient outcomes, including symptom burden, QoL, and end‐of‐life outcomes, all achieved with lower associated costs. Substantial work and research are still warranted at all levels to formulate quality metrics that create explicit standards in end‐of‐life care, to increase PC‐trained workforce and resources, to best integrate PC into medical education and health care systems, to improve communication and responsiveness to patient’s and family’s needs and preferences, to develop a system of seamless, coordinated end‐of‐life care, and to support quality research in PC and end‐of‐life care.

Acknowledgments

Eduardo Bruera is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant numbers RO1NR010162‐01A1, RO1CA122292‐01, and RO1CA124481‐01 and in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant number CA 016672.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Shalini Dalal, Eduardo Bruera

Collection and/or assembly of data: Eduardo Bruera

Data analysis and interpretation: Shalini Dalal, Eduardo Bruera

Manuscript writing: Shalini Dalal, Eduardo Bruera

Final approval of manuscript: Shalini Dalal, Eduardo Bruera

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

For Further Reading: Breffni Hannon, Nadia Swami, Ashley Pope et al. Early Palliative Care and Its Role in Oncology: A Qualitative Study. The Oncologist 2016;21:1387‐1395.

Implications for Practice: Patients and their caregivers who experienced early palliative care described the roles of their oncologists and palliative care physicians as being discrete and complementary, with both specialties contributing to excellent patient care. The findings of the present research support an integrated approach to care for patients with advanced cancer, which involves early collaborative care in the ambulatory setting by experts in both oncology and palliative medicine. This can be achieved by more widespread establishment of ambulatory palliative care clinics, encouragement of timely outpatient referral to palliative care, and education of oncologists in palliative care.

References

United States Committee on Ways and Means, United States Committee on Energy and Commerce, Committee on Education and Labor et al. . Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: As amended through November 1, 2010 including Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, health‐related portions of the Health Care, and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office,

Author notes

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.