-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Richard T. Penson, Lidia Schapira, Sally Mack, Marjorie Stanzler, Thomas J. Lynch, Connection: Schwartz Center Rounds at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, The Oncologist, Volume 15, Issue 7, July 2010, Pages 760–764, https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0329

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Shortly before his death in 1995, Kenneth B. Schwartz, a cancer patient at Massachusetts General Hospital, founded the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center®, a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting and advancing compassionate health care. The Center sponsors Schwartz Rounds®, a multidisciplinary forum in which doctors, nurses, chaplains, social workers, and other staff reflect on important psychosocial issues that arise in caring for patients. Attendees participate in an interactive discussion about issues anchored in a case presentation and share their experiences, thoughts, and feelings. The patient narratives may center on wonderful events and transcendent experiences or tragic stories, during which staff can only bear witness to the suffering. The Rounds focus on caregivers' experiences, and encourage staff to share insights, own their vulnerabilities, and support each other. The primary objective is to foster healing relationships and provide support to professional caregivers, enhance communication among caregivers, and improve the connection between patients and caregivers. Currently, >50,000 clinicians attend monthly Schwartz Rounds at 195 sites in 31 states, numbers that are rapidly growing. In this article we explore the reasons that contribute to the success of this model of multidisciplinary reflection.

Friday Lunchtime

In a room of 100 people, the noisy sounds of lunch hush as the clinician leader, a wiry young oncologist, opens the 70th Schwartz Center Rounds with a topical joke, a brief announcement, and a welcoming smile. He starts in earnest, leaning slightly forward, and introduces a senior Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) physician and the story he will tell with, “We often ask ourselves, ‘what would I do if I got cancer?’ ”

A pediatrician is the colleague who has cancer. He shifts in his seat. He moves a little slower, and is soft spoken, and bears the obvious scars of neurosurgery. Standard and experimental treatments for non-small cell lung cancer have failed him. He starts his very personal narrative, and explains that, after the initial diagnosis, “[he] did not know if [he] would ever be happy again, if [he] would ever laugh” [1]. He describes hearing the diagnosis for the very first time, and how the initial, incapacitating shock taught him as much as his observations of being enrolled in hospice care. In the same week, 6 months before this Rounds, he had started treatment with gefitinib (Iressa®; AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Wilmington, DE) and describes his resurrection from a fumbling, sedated, confused, and catheterized “wreck” to the benefit of a durable remission, snatched back, quite literally, within days of death [1].

The audience, clinicians from different disciplines and departments, revere the moment, as the physician leader and facilitator thank him. There is a pause, and the applause explodes, rapidly followed by all the questions everyone wants to ask, but usually only ask of themselves.

Care

Illness is isolating. Patients often fear that they are a burden to caregivers and caregivers may feel that they have failed [2]. Distress and suffering are grossly underestimated [3]. However, patients highly value the connection with their caregivers [4]. A prevalent myth is that medical professionals do not appreciate the human side of care. In the era of managed care, being connected with patients in the face of internal and external pressure to distance oneself is a challenge. Experienced practitioners regularly emphasize the significance of the patient–caregiver relationship when they refer to the art of healing. Students are advised to stay mindful of this relationship throughout their training. Yet despite the frequent reference to this subject by mentors, it is difficult in practice to devote the time and commitment to maintain excellence in the interpersonal skills that elevate the “care provider and consumer” to a level of respect and trust that so ennobles the doctor–patient relationship. The tyranny of the immediate medical demands understandably often takes precedence over thoughtful review of medical practice and compassionate care. Although clinicians are constantly assessing, prioritizing, and planning, both alone and in discussion with other members of the care team, they rarely discuss their feelings, or have time to ponder their experiences. In fact, they are so often preoccupied with medical aspects of the interaction with patients and their families, and even with their colleagues, that feelings of frustration, anger, and helplessness too often go unaddressed [5]. Sadly, very often there is no proactive coping mechanism beyond conforming to the prevailing culture, and often little mentorship is accessible for dealing with the emotional stress of caring for seriously ill patients. Burnout rates are high; strategies for physician renewal, resilience, and well-being are compromised by time commitments, systems problems, and bureaucracies. The Schwartz Center Rounds have become one such venue to share these issues.

Living Legacy

In the summer of 1995, a 40-year-old man faced his impending death from metastatic lung cancer. Kenneth B. Schwartz was a health care lawyer involved in health advocacy. He had been deeply impressed by his caregivers' personal expression of caring and had written a moving article about how compassionate care “gives me hope and makes me feel like a human being, not just an illness” [6]. “Looking back,” he said, “I realize that a high-volume, high pressure setting tends to stifle a caregiver's inherent compassion and humanity. But the briefest pause in the frenetic pace can bring out the best in a caregiver and do much for a terrified patient. It has been a harrowing experience for me and for my family. And yet, the ordeal has been punctuated by moments of exquisite compassion. I have been the recipient of an extraordinary array of human and humane responses to my plight. These acts of kindness—the simple human touch from my caregivers—have made the unbearable bearable” [6]. As a lawyer who had dealt with health care policy, contracts, and management issues, he was acutely aware that financial pressures could take the engagement and empathy out of health care. He wrote, “In such a cost-conscious world, can any hospital continue to nurture those precious moments of engagement between patient and caregiver that provide hope to the patient and vital support to the healing process?” After his death, Ken's family created the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, a nonprofit organization dedicated to strengthening the patient–caregiver relationship. The unique and innovative Schwartz Center Rounds started as a pilot program at MGH in 1997 [7–9]. It is now the Center's most successful and fastest growing program.

Schwartz Center Rounds

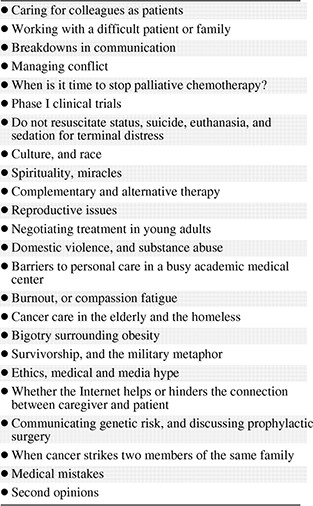

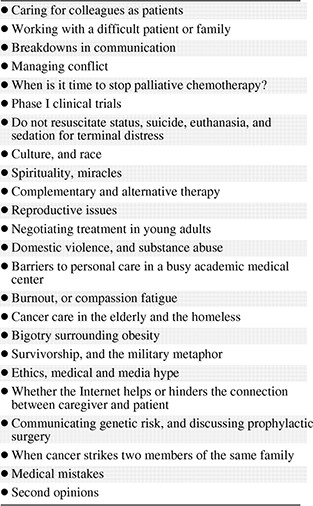

Started at MGH in Boston in 1997, the Rounds have now been replicated at 195 other medical institutions across the U.S. and at two in the U.K., and this continues to grow rapidly. The purpose of the Rounds is to provide a multidisciplinary forum in which caregivers discuss difficult emotional and social issues that arise in caring for patients. In the 12 years that the Rounds have been held at MGH, there has been a wide range of issues discussed with little repetition [7, 9]. Representative topics are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Even if a topic is repeated, the composition of the audience varies and the discussion can still be enriching.

Although each institution may tailor the Rounds, the format typically begins with a brief presentation (10 minutes) by two to three clinicians from different disciplines (e.g., doctor, nurse, social worker). One of the panelists, usually a physician, presents a very brief clinical history of the patient, including relevant information about the family situation, patient's attitude, and relevant circumstances. Each panelist then describes his or her own perspective, narrating their experience and the psychosocial issue that will be the topic of the day's discussion, which subsequently takes shape in an open-group discussion. During the hour, panelists and other caregivers in the audience ask questions and exchange experiences, thoughts, and feelings in relation to the topic. Patient and caregiver confidentiality are maintained at all times. A facilitator helps lead and focus the discussion and summarizes the salient points at the end of the hour. In some hospitals, Rounds are based in the cancer center and the focus is oncology patients. At most institutions, Schwartz Center Rounds are institution wide and the cases come from all specialties. Patients and family members do not attend as a rule, because it can inhibit caregivers. Occasionally, however, patients or family members present their story directly to the audience and then caregivers ask questions. This is always a very powerful experience.

Benefits

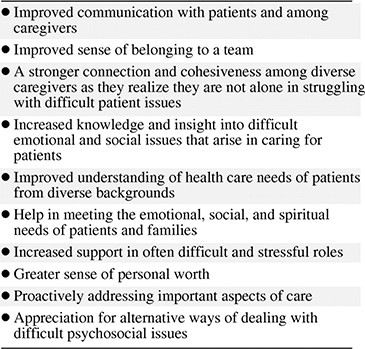

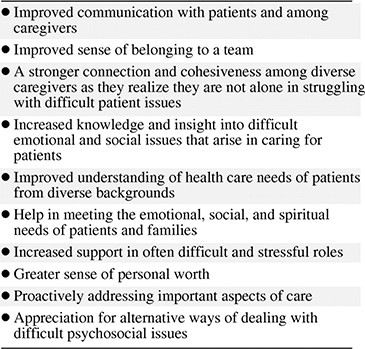

Response to the Rounds has been overwhelmingly positive. It is clear by the high level of participation and interaction that caregivers yearn for an opportunity to express themselves openly in a situation in which it is safe to do so and that they derive great benefit from the feedback and support they receive from colleagues. Participants have commented that, before the Rounds, there was no real opportunity in the regular workday to discuss these kinds of issues in depth. Recurring themes from these are listed in Table 3.

The Goodman Research Group recently conducted a retrospective survey of 256 caregivers at six sites where Rounds had existed for >3 years, with 44 semistructured interviews with participants at these sites and pre-/post-surveys of 222 caregivers from 10 hospitals newly implementing Rounds [12]. The highest percentage of attendees were nurses (35%), followed by physicians (23%), social workers (15%), psychologists (4%), physical therapists (6%), and clergy (5%). After attending Rounds, participants reported increased insight into psychosocial aspects of care, enhanced compassion, increased ability to respond to patients' social and emotional issues, enhanced communication among caregivers and a greater sense of teamwork, greater appreciation of colleagues' roles and contributions, and decreased feelings of stress and isolation. Participants also reported that Rounds discussions often led to specific changes in institutional practices or policies, though measurable and sustained changes in behavior have not been evaluated.

A commonly reported benefit is that caregivers no longer feel alone. Ultimately, the Rounds benefit patient care. In hospitals conducting Schwartz Center Rounds, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations surveyors have put a special note of commendation about the Rounds and their impact on staff morale in their report. Rounds commonly stimulate small, informal follow-up discussions among colleagues and enable engagement with the “central professional responsibility” to pursue excellence in patient care [10]. Rounds can help promote a sense of solidarity and connectedness, or rekindle a sense of vocation or mission. With that commitment comes a move toward the ideals embodied in LaCombe's physician, who is “right without arrogance, self-questioning without self-doubt, introspective and yet decisive, with strength laced with tenderness and understanding” [11].

Success

In a medical setting, how can you ensure respect and short circuit the natural competitiveness of high achieving individuals? How can you foster self-awareness without being “preachy”? Schwartz Center Rounds help achieve these goals. The Rounds create an atmosphere that values connection and open communication. The Rounds foster respect for persons, making them a “safe” place with the security that allows people to be candid. Clear leadership of the Rounds is a key element, and much of the success has come from the invested commitment of senior and respected clinicians. Their involvement in the mainstream of the Rounds has assured respect and attracted strong participation, validating the Rounds and ensuring a high profile. Despite this need for effective leadership, the Schwartz Center Rounds are an intentionally multidisciplinary meeting, with a nonhierarchical atmosphere and a level playing field mandated for all. A respectful and nonjudgmental atmosphere is engendered by the physician leader and facilitator and reinforced by the panel. Everyone has equal status and equal opportunity to express ideas and feelings. Inviting presenters/panelists representing different disciplines ensures a multiprofessional balance. Physician leaders and facilitators consciously encourage comments and questions and involve the whole group. Speaking openly, letting down your guard, thinking aloud, and being vulnerable in front of peers is inspiring and rewarding. Rounds make caregivers more aware of their discomforts, challenge isolation, and allow for real connection and real support, promoting personal growth through self-reflection and self-awareness.

Rounds are as much about process as product. The atmosphere is warm and welcoming. Food seems to be the inevitable and essential catalyst for good conversation. The presentations are kept short and didactic monologue is actively curtailed. Candid questions are appreciated much more than rehearsed rhetoric. However, there is a comfortable ownership of concerns. There is a tangible sense of a common experience and a common passion, in which together the team can deliver excellent care and everyone is renewed in the practice of their very best. Caregivers have time to reflect confidentially, without morbid self-examination or voyeuristic curiosity, away from the routine care of patients. For individuals, the relief of shared concerns and being understood and validated by colleagues are invaluable outcomes. Participants clearly appreciate the opportunity to bring insight and support to others and relish the sense of mastery that comes with excellence. The sense of community and a vital common goal facilitate the camaraderie of effective teams working together.

Intimate access to patients is a privilege and a responsibility that should be honored with commitment and compassion. Connecting at a vulnerable time, either terrifying or amazing, is often a moment of discovery that engages people and confers a sense that “this is who I really am,” or “this is what I was made to do.” What Schwartz Center Rounds allow is both a celebration of the positive and a sharing of the pain of the difficult experiences of illness.

Conclusion

Education, in its truest e duco sense of leading out, is an ongoing commitment in the pursuit of excellent health care. Schwartz Center Rounds have helped deepen and strengthen a hospital's resolve to practice the best in compassionate care. A better understanding of the health care team's various roles and an increased awareness of psychosocial issues have increased the sense of community. The key to success has been to create an atmosphere that supports and encourages candid participation, positively sharing different viewpoints, and owning emotional issues, and uncertainty. The fact that the Rounds have thrived in diverse environments, from academic medical centers to community hospitals to chronic care facilities, demonstrates that they can be replicated effectively and that they are fulfilling a tremendous need. The mission of one can become the mandate of many.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the staff of the Schwartz Center and those who contribute to the Schwartz Center Rounds. Where the narrative includes identifying features, permission to report their story has been granted by those involved.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Richard T. Penson

Manuscript writing: Richard T. Penson, Lidia Schapira, Sally Mack, Marjorie Stanzler, Thomas J. Lynch, Jr.

Final approval of manuscript: Richard T. Penson, Lidia Schapira, Sally Mack, Marjorie Stanzler, Thomas J. Lynch, Jr.

References

Author notes

Disclosures: Richard T. Penson: Employment/leadership position: Data Safety Monitoring Committee for Genentech; Consultant/advisory role: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; Research funding/contracted research: Genentech, Inc., Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, CuraGen Corporation, PDL BioPharma, Inc., ImClone Systems, Inc., Endocyte, Inc., AstraZeneca; Lidia Schapira: None; Sally Mack: None; Marjorie Stanzler: None; Thomas J. Lynch, Jr.: Leadership position: Board of Directors, Infinity, and Board Chair for Kenneth Schwartz Center; Intellectual property/patent: EGFR mutation patent; Consultant/advisory role: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche.

The content of this article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is balanced, objective, and free from commercial bias. No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by the independent peer reviewers.