-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

J L Smith, R Banerjee, D R Linkin, E P Schwab, P Saberi, M Lanzi, ‘Stat’ workflow modifications to expedite care after needlestick injuries, Occupational Medicine, Volume 71, Issue 1, January 2021, Pages 20–24, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqaa209

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is recommended to start within hours of needlestick injuries (NSIs) among healthcare workers (HCWs). Delays associated with awaiting the results of testing from the source patient (whose blood was involved in the NSI) can lead to psychological consequences for the exposed HCW as well as symptomatic toxicities from empiric PEP.

After developing a ‘stat’ (immediate) workflow that prioritized phlebotomy and resulting of source patient bloodwork for immediate handling and processing, we retrospectively investigated whether our new workflow had (i) decreased HIV order-result interval times for source patient HIV bloodwork and (ii) decreased the frequency of HIV PEP prescriptions being dispensed to exposed HCWs.

We retrospectively analysed NSI records to identify source patient HIV order-result intervals and PEP dispensing frequencies across a 6-year period (encompassing a 54-month pre-intervention period and 16-month post-intervention period).

We identified 251 NSIs, which occurred at similar frequencies before versus after our intervention (means 3.54 NSIs and 3.75 NSIs per month, respectively). Median HIV order-result intervals decreased significantly (P < 0.05) from 195 to 156 min after our intervention, while the proportion of HCWs who received one or more doses of PEP decreased significantly (P < 0.001) from 50% (96/191) to 23% (14/60).

Using a ‘stat’ workflow to prioritize source patient testing after NSIs, we achieved a modest decrease in order-result intervals and a dramatic decrease in HIV PEP dispensing rates. This simple intervention may improve HCWs’ physical and psychological health during a traumatic time.

Needlestick injuries are stressful experiences for healthcare workers.

Empiric human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) post-exposure prophylaxis, given while awaiting the results of source patient testing, can have adverse effects.

Instituting a simple facility-wide needlestick injury order policy decreased time-to-result intervals for source patient HIV testing by about 20% (from 195 to 156 min).

More impressively, the proportion of exposed healthcare workers receiving HIV post-exposure prophylaxis decreased by over half (from 50% to 23%) after our intervention.

Faster source patient HIV testing after needlestick injuries may prevent unneeded adverse effects and financial costs from empiric HIV post-exposure prophylaxis.

Our intervention shows that processes to expedite source patient HIV results merit investment of time and effort.

Introduction

Needlestick injuries (NSIs) remain a common hazard for healthcare workers (HCWs) despite advances in safety devices, training and techniques. Studies in the UK and USA suggest the prevalence of NSIs to be 10–30% among students, 50–80% among trainee physicians and 40–60% among nurses [1–5]. The most feared consequence of NSIs is seroconversion for viral infections such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). An estimated 330 000 HCWs are exposed to HIV each year after NSIs, although thankfully HIV seroconversion is rare [6,7]. However, the surge in guilt and uncertainty associated with an NSI can have serious psychological consequences [3,8,9]. Prior NSIs are a risk factor for depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among HCWs [2,10]. Longer wait times for confirmation of HIV-seronegative status are associated with lengthened psychiatric morbidity in this setting, highlighting the importance of expediting the results of testing after an NSI [11].

However, source patients—i.e. the patients whose blood was the source of the NSI-related exposure—are not able to be tested for logistical or ethical reasons in 25–45% of NSI cases [12,13]. Even when source patient testing is possible, several hours if not days may elapse between the NSI and these results. Professional guidelines suggest empiric HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) initiation within hours of at-risk exposures [14–16]. While likely able to prevent HIV transmission, PEP may also lead to adverse effects (most commonly, nausea and vomiting) in as many as 70–80% of HCWs [14]. Rarer complications with HIV PEP include hypersensitivity reactions and serious drug–drug interactions [16]. As such, exposed HCWs may face physical and psychological risks from NSIs even if source patients are subsequently found to be HIV-seronegative.

Multiple individuals are involved in post-NSI care beyond the exposed HCW: the source patient, the authorized PEP prescriber (Occupational Health or Emergency Department provider) who evaluates the exposed HCW and places orders for relevant viral testing if appropriate, the phlebotomist who draws this bloodwork and the clinical laboratory technician who accessions the blood sample and posts the results. After recognition of institutional delays in this process, we developed a ‘stat’ (an abbreviation of the Latin term statim, or immediate) workflow detailed in Table 1 to expedite the processing and results of source patient testing after an at-risk NSI. By definition, orders flagged as ‘stat’ should be handled and processed immediately by phlebotomists and laboratory technicians rather than being placed in a first-in-first-out queue with contemporaneous bloodwork orders. After implementing our new workflow, we analysed NSI data retrospectively to determine whether our ‘stat’ workflow had: (i) decreased HIV order-result intervals for bloodwork from the source patient and (ii) decreased the frequency of HIV PEP prescriptions by allowing for faster results (which could then be used for shared decision-making between authorized PEP prescribers and exposed HCWs).

| Domain . | Pre-intervention . | Post-intervention . |

|---|---|---|

| NSI reporting process | Occupational Health during business hours; Emergency Department otherwise | |

| Source patient ordersa | Individual ordersa entered by providers, including multiple options for HIV testing | A unified NSI order set with all needed orders included (including the correct HIV ELISA assay) |

| Source patient order priorities | Routine priority (the institutional default for all orders) | ‘Stat’ flag as the default for all orders within the NSI order set |

| Source patient phlebotomy | Drawn and analysed chronologically in a first-in-first-out queue along with other lab orders | Prioritized request to be handled ‘stat’ as emergent lab orders |

| Source patient bloodwork lab testing and result | ||

| Decision to prescribe HIV PEP empirically | Based on risk assessment and shared decision-making with the exposed HCW |

| Domain . | Pre-intervention . | Post-intervention . |

|---|---|---|

| NSI reporting process | Occupational Health during business hours; Emergency Department otherwise | |

| Source patient ordersa | Individual ordersa entered by providers, including multiple options for HIV testing | A unified NSI order set with all needed orders included (including the correct HIV ELISA assay) |

| Source patient order priorities | Routine priority (the institutional default for all orders) | ‘Stat’ flag as the default for all orders within the NSI order set |

| Source patient phlebotomy | Drawn and analysed chronologically in a first-in-first-out queue along with other lab orders | Prioritized request to be handled ‘stat’ as emergent lab orders |

| Source patient bloodwork lab testing and result | ||

| Decision to prescribe HIV PEP empirically | Based on risk assessment and shared decision-making with the exposed HCW |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HCW, healthcare worker; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NSI, needlestick injury.

aIncluding HIV serology testing and also recommended testing for the hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses.

| Domain . | Pre-intervention . | Post-intervention . |

|---|---|---|

| NSI reporting process | Occupational Health during business hours; Emergency Department otherwise | |

| Source patient ordersa | Individual ordersa entered by providers, including multiple options for HIV testing | A unified NSI order set with all needed orders included (including the correct HIV ELISA assay) |

| Source patient order priorities | Routine priority (the institutional default for all orders) | ‘Stat’ flag as the default for all orders within the NSI order set |

| Source patient phlebotomy | Drawn and analysed chronologically in a first-in-first-out queue along with other lab orders | Prioritized request to be handled ‘stat’ as emergent lab orders |

| Source patient bloodwork lab testing and result | ||

| Decision to prescribe HIV PEP empirically | Based on risk assessment and shared decision-making with the exposed HCW |

| Domain . | Pre-intervention . | Post-intervention . |

|---|---|---|

| NSI reporting process | Occupational Health during business hours; Emergency Department otherwise | |

| Source patient ordersa | Individual ordersa entered by providers, including multiple options for HIV testing | A unified NSI order set with all needed orders included (including the correct HIV ELISA assay) |

| Source patient order priorities | Routine priority (the institutional default for all orders) | ‘Stat’ flag as the default for all orders within the NSI order set |

| Source patient phlebotomy | Drawn and analysed chronologically in a first-in-first-out queue along with other lab orders | Prioritized request to be handled ‘stat’ as emergent lab orders |

| Source patient bloodwork lab testing and result | ||

| Decision to prescribe HIV PEP empirically | Based on risk assessment and shared decision-making with the exposed HCW |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HCW, healthcare worker; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NSI, needlestick injury.

aIncluding HIV serology testing and also recommended testing for the hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses.

Methods

We included all HCWs with NSIs reported at our institution, an urban academic-affiliated Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the USA, during a 6-year period between January 2013 and December 2018. Any blood or body fluid exposure for which HIV PEP would be considered (i.e. needlesticks, lacerations or fluid exposures onto open wounds) were included classified as NSIs. NSIs for which source patient testing could not be performed were excluded.

In order to develop this intervention, we held serial collaborative and interdisciplinary meetings with Employee Occupational Health providers, Emergency Department providers and Laboratory Medicine personnel (including phlebotomists and lab technicians). After examination of specific cases and interviews of involved personnel, we identified two specific root causes of delays with regard to source patient testing: (i) heterogeneity in source patient orders, e.g. multiple options for HIV testing; and (ii) heterogeneity in order priorities, with the majority of labs being ordered with ‘routine’ priorities and treated by phlebotomy/laboratory personnel in a first-in-first-out manner. As shown in Table 1, we addressed both issues by implementing a unified NSI order set for use by authorized providers that listed the correct source patient testing orders (for HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C) with ‘stat’ as the default priority.

We obtained ethical clearance from our institution’s Institutional Research Board (the equivalent of a Research Ethics Committee) to perform this retrospective analysis using data from our institution’s medical record and sharps-related injury log. Data abstraction included the time of NSI, time of source patient HIV bloodwork being ordered, time of source patient HIV bloodwork being drawn by a phlebotomist, time of source patient HIV bloodwork resulting in the medical record and whether or not one or more doses of PEP was prescribed to the exposed HCW. Accounting for a 2-month rollout of our new workflow during July 2017 and August 2017, we divided our 6-year study period into two periods: (i) a 54-month pre-intervention period from January 2013 to June 2017 and (ii) a 16-month post-intervention period from September 2017 to December 2018.

Our primary endpoint was the interval, in minutes, between the time of source patient bloodwork order and time resulted for each NSI. Because we assumed a non-parametric distribution for these intervals, we used the Mann–Whitney U-test to compare median intervals between the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods. Secondary endpoints included (i) proportions of exposed HCWs being prescribed one or more doses of PEP and (ii) aggregate monthly frequencies of HIV PEP prescriptions dispensed across our institution. PEP prescription proportions were analysed using Fisher’s exact testing, while PEP prescription frequencies were analysed using student’s t-testing. All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA) and Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). We determined statistical significance using two-sided testing with P <0.05 in all cases.

Results

We identified a total of 251 NSIs that were reported over a 6-year period encompassing the pre-intervention period (n = 191, mean 3.54 NSIs per month) and post-intervention period (n = 60, mean 3.75 NSIs per month). Monthly NSI frequencies were similar between the two periods (P = 0.75). Of the 251 NSIs, 76% (n = 190) were reported to Occupational Health providers while 24% (n = 61) were reported to Emergency Department providers (presumably for after-hours exposures). Fully credentialed employees comprised 53% of exposed HCWs (n = 135), while trainees (including medical/dental/nursing students and physicians in training) comprised 44% (n = 111). NSIs most commonly occurred in the operating room/post-anaesthesia care unit (30% of cases, n = 76). Other locations for NSIs included dental clinics (15%, n = 38), dermatology clinics (9%, n = 22) and intensive care units (7%, n = 18).

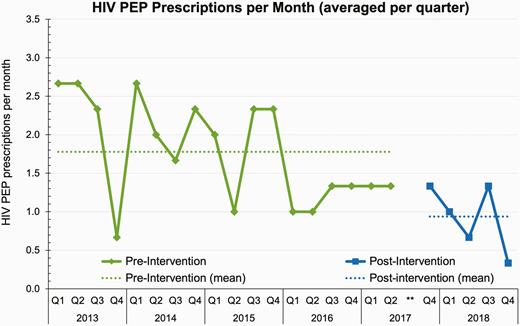

Median source patient HIV ordering-result intervals decreased 20% from 195 minutes pre-intervention (interquartile range: 144–325 min) to 156 min post-intervention (interquartile range: 106–325); this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney U-test). The proportion of exposed HCWs who received one or more doses of PEP decreased significantly from 50% (96/191) pre-intervention to 23% (14/60) post-intervention, with P <0.001 by Fisher’s exact test. Given this surprisingly large reduction, we conducted two post hoc subgroup analyses to analyse groups possibly at higher risk of PEP initiation: (i) trainee HCWs, given possibly higher levels of distress about NSIs; and (ii) HCWs seen by Emergency Department providers, for whom acuity considerations may have favoured empiric initiation of PEP. Proportions of HCWs prescribed PEP decreased from 47% to 30% among trainee HCWs and from 70% to 43% among HCWs seen by Emergency Department providers; however, these trends did not reach statistical significance. Lastly, we calculated frequencies of HIV PEP prescriptions dispensed per month across our institution to any exposed HCW. As shown in Figure 1, the mean frequency of PEP prescriptions dispensed per month decreased significantly (P < 0.01 by student t-testing) from a mean of 1.78 during the pre-intervention period to a mean of 0.94 during the post-intervention period.

HIV PEP prescriptions per month. For ease of viewing, monthly HIV PEP prescription frequencies are averaged for each quarter. Data from the third quarter of 2017 were censored (shown as **) to account for implementation and rollout of our intervention. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; Q, quarter.

Discussion

Our implementation of a standardized ‘stat’ workflow for source patient testing led to a 20% decrease in the average interval between NSI bloodwork order and source patient HIV test results. More impressively, the proportion of HCWs who received one or more doses of PEP dropped by over half from 50% in the pre-intervention period to 23% in the post-intervention period. This reduction was both statistically and clinically significant, suggesting that providers and exposed HCWs felt more comfortable waiting for HIV test results through our new workflow rather than prescribing PEP empirically. Because rates of HIV prevalence and post-NSI HIV seroconversion are low in the USA [7], this reduction in PEP prescriptions likely had a negligible impact on HIV seroconversion. Conversely, this reduction likely alleviated HCW distress, HCW time spent away from work and the incidence of PEP-associated adverse effects.

Our intervention is novel because of its emphasis on a potentially thorny component of NSIs: namely, testing of the source patient for communicable viral diseases outside of their routine clinical care [17]. In contrast, most research around NSIs to date has focused either on decreasing NSI occurrences or on improving NSI reporting rates [3,18]. Our single-site experience focuses on a different component of post-NSI care, namely the use of simple workflow modifications to help alleviate the guilt and anxiety experienced by HCWs while awaiting source patient testing results. While NSIs are an emergency for the exposed HCW, source patient bloodwork is not necessarily prioritized for third parties beyond the HCW and his/her clinical provider: for example, phlebotomy staff and clinical laboratory technicians. Using the ‘stat’ nomenclature to unify and expedite disparate components of this process allowed these teams to recognize the importance of this testing to assist their colleagues. Source patients, who in our experience are generally willing to undergo additional testing if involved with an NSI in the modern era, may have benefited indirectly from a more coordinated and structured process as well.

Limitations of our intervention include our inability to comment on NSIs that were not reported to our institution. Our pre-/post-design did not allow us to eliminate other factors that may have contributed to expedited testing and lowered rates of HIV PEP prescriptions, for example possible increases in staffing over time in our phlebotomy and laboratory departments. Our intervention was not intended to impact other causes of delays—for example, source patients leaving the medical centre before NSI-related bloodwork could be drawn—but it may indirectly have modified these factors as well. It is possible that PEP-related preferences by HCWs or their authorized providers may have changed over time; however, given that HIV PEP is a fairly well-established principle in the modern era, we believe that any such changes are unlikely. Lastly, we did not directly interview exposed HCWs or source patients as part of this study. Future directions for our group include more granular investigation of the HCW experience after an NSI, possibly with a secondary emphasis on improving NSI reporting rates.

In conclusion, the implementation of a standardized ‘stat’ workflow around source patient testing led to a modest decrease in the time needed for source HIV testing results but a substantial reduction in the rate of dispensed HIV PEP prescriptions. Our simple intervention to expedite NSI-related processes is readily scalable to other institutions and may improve HCW health, both physically and psychologically, during a traumatic time.

Funding

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank the employees of the Employee Occupational Health Department, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA. The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Competing interest

None declared.

References