-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alessandra Agnese Grossi, Mehmet Sukru Sever, Rachel Hellemans, Christophe Mariat, Marta Crespo, Bruno Watschinger, Licia Peruzzi, Erol Demir, Arzu Velioglu, Ilaria Gandolfini, Gabriel C Oniscu, Luuk Hilbrands, Geir Mjoen, The 3-Step Model of informed consent for living kidney donation: a proposal on behalf of the DESCaRTES Working Group of the European Renal Association, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 38, Issue 7, July 2023, Pages 1613–1622, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfad022

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Living donation challenges the ethical principle of non-maleficence in that it exposes healthy persons to risks for the benefit of someone else. This makes safety, informed consent (IC) and education a priority. Living kidney donation has multiple benefits for the potential donor, but there are also several known short- and long-term risks. Although complete standardization of IC is likely to be unattainable, studies have emphasized the need for a standardized IC process to enable equitable educational and decision-making prospects for the prevention of inequities across transplant centers. Based on the Three-Talk Model of shared decision-making by Elwyn et al., we propose a model, named 3-Step (S) Model, where each step coincides with the three ideal timings of the process leading the living donor to the decision to pursue living donation: prior to the need for kidney replacement therapy (team talk); at the local nephrology unit or transplant center, with transplant clinicians and surgeons prior to evaluations start (option talk); and throughout evaluation, after having learned about the different aspects of donation, especially if there are second thoughts or doubts (decision talk). Based on the 3-S Model, to deliver conceptual and practical guidance to nephrologists and transplant clinicians, we provide recommendations for standardization of the timing, content, modalities for communicating risks and assessment of understanding prior to donation. The 3-S Model successfully allows an integration between standardization and individualization of IC, enabling a person-centered approach to potential donors. Studies will assess the effectiveness of the 3-S Model in kidney transplant clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Living donor kidney transplantation is the best renal replacement therapy for patients with end-stage kidney disease [1]. Living kidney donors (LD) undergo surgery for the benefit of another person. Living donation challenges the ethical principle of non-maleficence in that it exposes healthy persons to risks for the benefit of someone else. This makes safety, informed consent (IC) and education a priority [2, 3].

The duty to communicate the risks and benefits of donation is a social, medical, legal and ethical requirement. From an ethical perspective, informed consent fulfills the principle of respect for autonomy. Therefore, clinicians must disclose the information and risks that are important for making an informed decision [2, 4]. In-depth, well-informed decisions should include receiving information of all potential risks associated with living kidney donation, emphasizing the short- and long-term medical and surgical risks for the donor [5, 6].

Living kidney donation has multiple benefits for the potential donor including personal satisfaction for helping the recipient to prevent or discontinue dialysis, diminished caregiving burden and improved household dynamics (in case of a family relationship) [7]. At the same time, there are several known risks related to living kidney donation. Short-term risks relate mostly to the surgical procedure. These include, but are not limited to, pain, bleeding or postoperative infections [8]. In addition to this, there are long-term risks. Living kidney donors have increased long-term risk for hypertension [9, 10], preeclampsia [11], end-stage renal disease [12, 13], cardiovascular diseases [14, 15] and psychiatric problems [16]. One study found increased long-term mortality after donation, only evident after more than a decade of observation time [12]. Standard criteria for kidney donation are based on being healthy and free from disease [17]. The evaluation process includes biochemical tests, imaging tests, measurement of kidney function and usually cardiovascular assessment [17]. This carries, among other things, the potential for incidental findings including previously unknown medical problems or non-paternity [18].

In Europe, despite the duty to communicate risks, research has found substantial variation in the written and oral information provided across different countries, transplant centers and even among providers at the same centers, especially regarding long-term risks [19–24]. Complete standardization of consent is likely to be unattainable [5, 19, 25]. Still, studies have emphasized the need for a standardized IC process to enable equitable educational and decision-making prospects for the prevention of inequities across transplant centers [5, 24, 26, 27]. We propose a model, named the 3-Step (S) Model, which stands as an effort to provide conceptual and practical guidance to nephrologists and transplant clinicians (i) to determine the ideal timing and communicative setting(s) for information and education, (ii) to ensure that the provided information is adequate and (iii) to ascertain that the information is understood.

CONCEPTUAL ISSUES SURROUNDING INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent is not just a signature on a formal document. It is a process unfolding over time between the patient and the responsible clinicians, entailing a joint respect for “clinical indications and individual patients’ subjective considerations, values, needs, preferences, specific life circumstances and goals” [28]. Therefore, the request and acquisition of consent is an educational and relational process unfolding throughout several discussions with the patient [29, 30]. This highlights the importance of the length and the quality of the relationship between patient and provider. Studies have emphasized that shared decision-making is the most ethical and appropriate model in kidney transplant clinical practice, including decision-making for living donor kidney transplantation [6, 28, 31]. For instance, the more treatment alternatives, the higher the level of uncertainty, and the greater the risks of the procedure, the more informed consent and shared decision-making coincide [32].

Multiple aspects make donor participation in decision-making critical. Dilemmas and the need for support from healthcare professionals are frequent [33–35]. Further, potential donors and their clinicians may have different views on living donation [18, 36]. As in most areas of clinical practice [37], uncertainty about risks cannot be eliminated fully [6]. Based on these considerations, the active participation of potential donors in the process of informed consent is crucial.

Elwyn et al. [38] have conceptualized shared decision-making as “a process in which decisions are made in a collaborative way, where trustworthy information is provided in accessible formats about a set of options, typically in situations where the concerns, personal circumstances, and contexts of patients and their families play a major role in decisions.” This definition stresses on the need to communicate in a manner that best suits the patient's needs to enable his/her understanding, to foster reflection and engagement, along with active clinician listening to allow an integration of clinical indications with the perspective of individual patients.

While studies suggest that implementation of shared decision-making should occur early in the process [31, 39], multiple factors may hinder early discussions with kidney donor candidates and their social network. These comprise healthcare professionals’ (un)willingness because of time constraints [40], fragmented interactions with multidisciplinary teams [31], inadequate communication between nephrology and transplant teams, absence or heterogeneity of referral guidelines across centers, insufficient information, lack of training on how to communicate the risks and benefits, and negative attitude of some clinicians towards living donor kidney transplantation. Further, barriers may exist at the level of patients and their potential donors such as different cultural backgrounds, psychosocial factors, language barriers, belief systems, unrealistic expectations, inability to initiate discussions about kidney disease [25] and (in)ability to process complex medical information [31]. In addition, although public opinion is generally in favor of living donor kidney transplantation (90%) [41], negative attitudes and fears may still exist [42].

All of these factors have the potential to challenge the opportunity for standardization of the timing, content and modality to perform conversations. Besides, well-defined indications for its effective implementation in clinical practice are lacking.

THE 3-S MODEL OF INFORMED CONSENT FOR LIVING KIDNEY DONATION

The 3-S Model is based on the Three-Talk Model of shared decision-making by Elwyn et al. [38]. This comprises three main stages: (i) team talk (the time the patient is informed about options and the provider elicits his/her individual preferences and goals), (ii) option talk (the time when available options are comparatively presented by use of risk communication principles), and (iii) decision talk (the time the patient gets to the final decision through informed preferences supported and guided by the physician's knowledge and expertise) [38].

Many models exist for shared decision-making (some more generic and other more specific to particular healthcare settings, excluding living kidney donation) [43]. Yet, while most models share some of the critical components of shared decision-making (i.e. description of treatment options, making a decision, considering patient preferences, tailoring information, deliberation, etc.), only the Three-Talk Model specifically addresses the use of risk communication principles to enhance the quality of risk communication in clinical practice to facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Besides, relative to other models, only two (including the Three-Talk Model) consider shared decision-making as a fluid transition between the different phases of the process [43]. This has the potential to point out that shared decision-making is an ongoing process that—within the setting of decision-making for living kidney donation—does not come to an end at the time of nephrectomy. Besides, it serves to highlight that, when this is needed, one can repeat the actions performed during the “option talk” even at the time of the “decision talk.” The reason justifying the choice of the Three-Talk Model lies in these aspects.

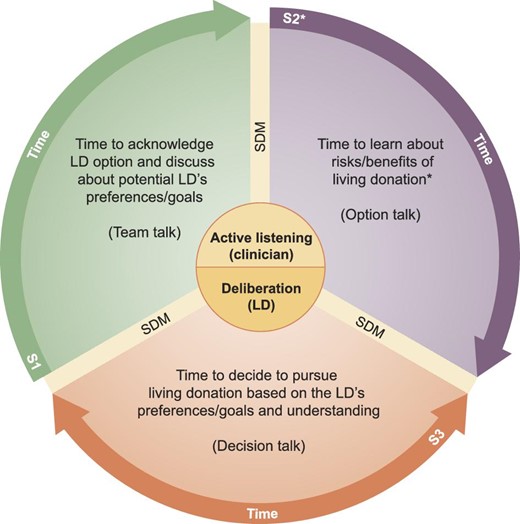

In our Model (Fig. 1), each of the three steps of the Three-Talk Model Model by Elwyn et al. [38] coincides with the three ideal timings of the process leading the LD to the decision to pursue living donation: receiving information prior to the need for kidney replacement therapy in the recipient (team talk), at the local nephrology unit or transplant center, with transplant clinicians and surgeons before starting the evaluation (option talk), and during the evaluation, after having learned about the different aspects of donation, and especially if there are second thoughts or doubts (decision talk). Providing consent should include both the evaluation and the surgery. Nephrologists, dialysis providers, transplant clinicians and surgeons should acknowledge their moral and professional duties and responsibilities relative to the need to provide adequate information of the risks of living donation to potential donors, elicit their perspectives and assess proper understanding, as described below:

The 3-S Model of informed consent for living kidney donation. The figure illustrates the three ideal timings of the process leading the donor candidate to the decision to pursue living kidney donation. Shared decision-making should start with the primary nephrologist prior to the need for kidney replacement therapy or at the local dialysis unit (S1), and, at the transplant center, with transplant clinicians and surgeons throughout the process of evaluation (S2) and prior to nephrectomy (S3). *S2 should not be intended as a single educational session but as a combination of two or more sessions (depending on the LD's health literacy, intellectual capacity, need for information and/or additional clarification) combining the use of various decision aids to improve understanding. S, step; SDM, shared decision-making.

STEP 1—TIME TO ACKNOWLEDGE LIVING DONOR OPTION AND DISCUSS POTENTIAL DONOR'S INITIAL DECISIONS

This step can be partly carried out as structured educational sessions at the hospital for patients and their families, or as home-based education where the team meets up with a patient and his/her relatives and friends at their home [44]. Such sessions are ideal for presenting the option of living donation, and for sharing some basic facts about living donation. However, with many people present, optimal interaction regarding individual preferences may not be easily attained. Consequently, some of the information given would profit from a one-to-one conversation, either by phone, digitally or in person. In this stage it is important to also deliver written information for self-study, or give out links to relevant websites.

The KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors highlights that the decision to donate should be shared between the donor candidate, his/her primary physician and the transplant program [6]. Research suggests that, ideally, information about treatment options including education about living donation should begin with dialysis providers and/or the primary nephrologist who could refer kidney transplant candidates and potential donors to transplant centers for further education and evaluation [45, 46]. However, among patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, it would be more desirable to start education about living donation prior to the need for kidney replacement therapy (i.e. estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2) [47].

Early information improves the chances to pursue living donation [31, 39]. Therefore, the promotion among the public may enable the acquisition of information about the LD option prior to the need for kidney transplantation among patients and their potential donors. Studies advise that education by testimonials from previous donors and non-argumentative public initiatives by non-profit organizations may be valid solutions to increase donor inquiries [48]. This has the potential to empower potential LDs to ask questions to the appointed nephrology team about the opportunity to pursue living donation when a beloved person is first diagnosed with advanced chronic kidney disease.

Studies indicate that initial decisions may be driven by emotions because of the desire to help the recipient [4, 34, 49–51]. Accordingly, this time-point is not suitable for making valid decisions. Therefore, before evaluations are initiated, recipients and their potential donors must be provided with verbal and written informative material to allow adequate time to collect and process relevant information [52, 53], improve risk recall and enhance understanding [54]. Evidence exists of question sheets being valuable means to improve patient participation and question-asking during consultations [55]. Therefore, physicians should hand out standardized prompt question sheets to empower potential donors to ask important questions later on (an example is provided in Supplementary data, Appendix A).

Potential donors must be knowledgeable that informed consent will be unfolding throughout several educational sessions where the risks and benefits of living donation will be presented and discussed, and will culminate in the candidate's decision of whether or not to donate.

It is essential to inform the potential donor that they will be required to embrace a long-term relationship with the team, including outpatient follow-up after donation to detect potential long-term complications because some risks may be uncertain or evolving [6, 56], and that the transplant team will guarantee assistance to the donor.

The potential donor must be informed that an independent LD advocate may assist the decision-making process as it progresses over time [57–59].

The donor must be informed that the first goal of the transplant team (and the donor advocate) will be to guarantee the donor's safety and that the team will refuse donation in case of a negative benefit/harm balance, sometimes even despite the donor's willingness to donate.

Potential donors must be reassured that, should any change occur in their decision to pursue living donation (see Step 2) [35, 57], they will be in the position to withdraw consent at any time. The transplant team will assist in communicating the decision to the intended recipient, both regarding what will actually be said, and how the message is delivered. The priority in such cases will be on the donor’s autonomy and his/her right to privacy [60].

STEP 2—TIME TO LEARN ABOUT THE RISKS AND BENEFITS OF LIVING DONATION

This step is carried out through several conversations between the potential donor and his/her nephrologist/transplant professional responsible for the evaluation. Relevant risks will be disclosed. The potential donor will share their views and opinions. Individual appointments with a nurse or social worker with special interest in living donation to learn about living donation and kidney disease are also likely to be beneficial.

The process of assessment for living donation at transplant centers allows time to elapse from the moment the donor candidate is informed about the opportunity to pursue living kidney donation through to the time of nephrectomy [28]. However, while recommended, research has noted that most (57%) transplant centers do not require potential donors to exercise a so-called “cooling-off” period to process the complex information received throughout informed consent, or do so only in particular cases (32%) [61]. Schweitzer et al. [35] suggest that the potential donor's response to information about worst-case scenarios of living donation may vary. Many react with either “optimistic fatalism” (i.e. unwillingness to deal with potential complications in detail) or “anxious avoidance” (i.e. refusal to discuss complications), and only in a minority of cases, with “active consideration,” leading to a revision of their initial decision to donate [35]. Similarly, research on living liver donors has shown that the desire for information is often associated with the willingness to be prepared for the procedure [62, 63]. Other studies have found that hesitation or uncertainty are common feelings among potential donors, and frequently go together with their intention to donate [34, 64, 65].

We acknowledge that the length of the informed decision-making process may vary according to individual features (i.e. subjective need for information, ability and/or willingness to process complex medical data, and/or to resolve hesitancy). Yet, sufficient time is critical for coming to a valid (i.e. truly informed) decision [57]. For instance, this period is essential in that it serves the functions of allowing time for proper presentation of the risks and benefits of living donation, for the potential donor to contemplate this information, assess comprehension and verify his/her persistent motivation. Prior studies of living liver donors have shown that, after receiving written information (i.e. a book, a copy of Power Point slides about donation and articles about local studies on living donation), participating in discussions surrounding living donation in a group setting with other potential LDs, and being exposed to a Power Point presentation and a YouTube video about the donation process, potential donors were given a “cooling off” period of approximately 10 days [66]. Yet, according to the National Health Service Blood and Transplant in the UK, the mean time needed for tests to be performed and the operation to be arranged is between 3 and 6 months [67]. We contend that this may be a reasonable time for the LD to process all the relevant information. However, only the formal assessment of understanding (see Step 3) will determine whether the time was adequate for the individual LD. Assessment of comprehension should not be conceived and presented to the potential LD as a test per se, or as a tool to rule out potential donors. Rather, it should be intended as a means to enable tailoring additional donor–provider communication to address the LD's remaining informative needs and make sure that he/she is best prepared for the donation process [66].

To promote the autonomy of the potential donor, it is important to ensure that the information provided about evaluations, and the short- and long-term risks associated with living donation is adequate and understandable. Research has shown that interactive strategies (i.e. employing test/feedback and “teach-back” techniques, and interactive digital interventions) are more effective than non-interactive ones [68].

Besides, while the surgical, perioperative and short-term risks of living donation are generally straightforward, communication and understanding of the long-term risks are more challenging [69]. User-friendly tools such as web-based calculators could be of value [70]. Although, not fully developed yet, these could potentially diminish ethical concerns and individual biases among clinicians (i.e. they may indicate a smaller risk than was presumed by the clinician), and, at the same time, allow more focused information, according to individual clinical and demographic features [71, 72].

Ideally, clinicians should avoid qualitative, subjective estimates of risks such as the use of adjectives like “low” or “high” when informing potential donors. For instance, data should be presented by use of absolute risk estimates, frequencies and pictographs to facilitate comprehension [53]. However, since such specific information rarely is available, one must often compromise. For instance, in the absence of clinical contraindications to donation, despite uncertainty, by presenting the potential risks and benefits of living donation, and by recognizing areas of absent or emerging data, along with the active involvement of the LD in decision-making, it is possible to obtain a meaningful informed consent that respects the autonomy of the LD [73].

Further, to ensure that all relevant areas have been covered, standardized checklists should be used consistently at all stages of end-stage kidney disease care [6, 24, 25] (our proposal is reported in Supplementary data, Appendix B). In addition, because potential donors may feel the necessity to share concerns with the transplant team [31, 33, 34], providers should remain available throughout the process [31].

Physicians are frequently concerned that shared decision-making is practically unattainable because it is time-consuming and therefore conflicting with busy hospital schedules. Yet, multiple strategies exist to enhance the quality of time rather than simply the quantity of time [40]. Patient decision aids (i.e. brochures, fact sheets, handbooks, videos, websites, mobile applications supporting patients) improve standardization and empower potential donors even outside the clinical encounter. A systematic review of 105 studies found that patients who are exposed to such tools report improved knowledge, better information and enhanced ability to clarify their own values. Besides, they improve the patient's ability to play an active role in decision-making, enhance the accuracy of risk perception, diminish hesitancy and have a positive effect on patient–physician communication with only little additional time (2.6 min) when compared with usual care [74]. For instance, decision aids have proven to be effective means to support decision-making among options for patients and their families, and to supplement clinician counseling in living donation [52]. These have shown to increase donor inquiries, knowledge, willingness to discuss live donation [52] and self-efficacy in communication, and to diminish concerns [75].

Individuals from more vulnerable groups (i.e. socioeconomically disadvantaged subjects, migrant and ethnic minority individuals) may benefit from interventions that are tailored to lower levels of health literacy, and to their individual linguistic and cultural specificities [52, 66]. Yet, providers should note that the use of patient decision aids in isolation (i.e. without additional individual supports or navigation services to overcome communicative, logistic and financial obstacles) may not necessarily prove useful in more vulnerable groups (i.e. migrants and ethnic minorities) [76]. For example, research suggests that the setting of the educational interventions (with home-based being preferred) may be critical to successfully tailor information to the specific needs of potential donors and recipients in these vulnerable communities [44].

STEP 3—TIME TO CONFIRM WHETHER OR NOT TO PURSUE LIVING DONATION

Many donors have made their decision of whether to donate several years or months in advance of coming to their first appointments at the hospital. However, it is important that there is room for discussing their decision of whether to donate or not. It is equally important that they learn about the risks of donation early in the process, allowing them to withdraw from the evaluation process as early as possible. A survey study of transplant professionals in Europe revealed that clinicians do not always assess whether the donor has actually understood the information about potential long-term risks. In most cases, they do so by simply asking whether they have fully understood without any additional formal evaluation [24]. However, not everyone is willing or capable to acquire and/or process information about risks [62, 63]. Besides, studies report insufficient knowledge of the long-term risks of donation among potential donors even at the time of nephrectomy [19]. Therefore, at the time of the ultimate confirmation to pursue donation, it is likely to be beneficial to perform a formal assessment of whether the potential donor has achieved adequate understanding of the short- and long-term risks and benefits of the procedure. Again, this would serve to document the informed consent process (documentation of educational sessions, material and in person discussions should be included in the LD's medical record).

Although ideal methods to evaluate understanding in potential donors are not well determined [45], various strategies have been tested. Comprehension assessment tools including the administration of questionnaires that evaluate understanding may be effective (an example is provided in Supplementary data, Appendix C) [77]. One of these has been pilot tested to determine the comprehension of risks among living liver donors who received information as part of a structured informed consent process. Overall, the tool, which comprised 46 knowledge items regarding the risks of living donation, has proven to be effective for the identification of information deficiencies among potential LDs, allowing transplant teams to address comprehension gaps [66]. Furthermore, other strategies may include the use of “teach-back” techniques, requiring patients to repeat back the information acquired throughout the process in their own words [78]. Research has proven “teach-back” techniques to be effective for the improvement of learning-related outcomes (i.e. knowledge recall and retaining), objective health-related outcomes (i.e. hospital readmissions and quality of life) and for the reinforcement or confirmation of patient education [79, 80]. Studies have put forward the potential usefulness of “teach-back” as a pragmatically applicable method for improved education and assessment of understanding among potential LDs [53, 81].

Provided that candidates have received objective and equitable information, and understanding has been properly assessed by use of the techniques illustrated previously, the candidate can come to a final decision that is truly informed. This guarantees respect for clinical indications, autonomy and a meaningful signature on the informed consent form prior to nephrectomy. The transplant team will assist the donor candidate in informing the potential recipient about the donor's decision. In case of donor's unwillingness to proceed, the transplant team should help protect the autonomy of the donor [60].

DISCUSSION

The 3-S Model of informed consent for living kidney donation emphasizes that shared decision-making between the potential LD and the transplant team needs time, providers’ communicative abilities (including active listening along with the capacity to elicit the potential donor's perspective) and collaboration for its actual implementation to be effective. For instance, because decision-making develops over time, a step-by-step approach is necessary to enable the presentation of the LD option early in the process (i.e. ideally, prior to the need for kidney replacement therapy), to allow sufficient time, and, because donation is a lifelong process that does not come to an end at the time of nephrectomy, to build a well-established long-term partnership with the donor. A standardized method for informed consent is also reassuring for the recipients, knowing that their donor is well-informed, with thorough communication with the transplant professionals over a sufficient period of time.

Further, the model highlights the need for transplant programs to deliver indications for standardization of the timing, content, modalities for communicating risks and assessment of understanding prior to donation. This may orient and support physicians’ actions at the different steps of the shared decision-making process for individuals pursuing living kidney donation. For instance, the model may also help overcome barriers at the provider level. For example, the use of decision aids, prompt question sheets and exposure to group discussions with other potential LDs may empower potential LDs outside clinical encounters to increase understanding and, when aspects remain unclear, to ask important questions later, during in-person conversations. This may diminish the concern, among nephrologists and transplant professionals, that engaging in shared decision-making will take too much time. Also, the need to refer to evidence-based data regarding living donation, the improved ability to communicate risks and benefits in a manner that is tailored to the LD's individual features, and the opportunity to formally assess LD understanding prior to nephrectomy may reduce the individual biases and/or negative attitude of some clinicians towards living donor kidney transplantation. Besides, the use of standardized checklists among nephrologists, dialysis providers and transplant clinicians may improve communication between nephrology and transplant teams and make interactions among multidisciplinary teams more consistent and meaningful.

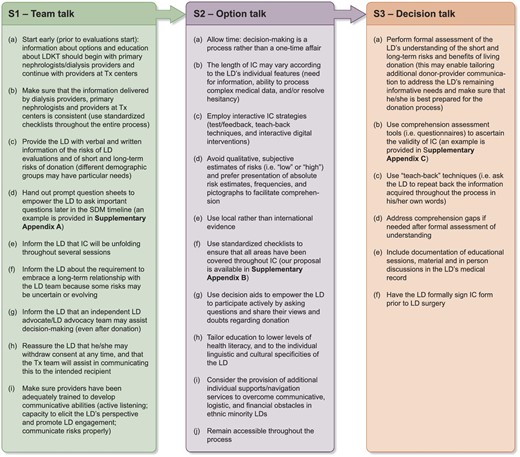

According to our framework, experience and interpretation of the literature, we propose a list of recommendations regarding these aspects, which are listed in Fig. 2 (a documentation sheet that may be printed out by the centers willing to implement this model is reported in Supplementary data, Appendix D) and further exemplified in Case Vignettes 1 and 2.

Recommended clinicians’ actions at the three stages of the informed consent process for living kidney donor candidates. LDKT, living donor kidney transplant; SDM, shared decision-making; Tx, transplant.

Although standardization and individualization may seem conflicting, the 3-S Model successfully allows an integration of the two. For instance, standardization of the timing, content, modalities for communicating risks and assessment of understanding all have the potential to diminish individual biases and variations among transplant clinicians. At the same time, the necessity to evaluate LDs individually and to explore their preferences introduces and promotes the relational dimension between clinicians and potential LDs. This enables a person-centered approach to potential donors, who will not receive information as if they were a homogeneous group.

Future studies will assess the effectiveness of the 3-S Model in kidney transplant clinical practice in terms of (i) clinicians’ (i.e. satisfaction, ability to elicit donors’ views, to formally assess understanding, and to standardize the timing) and (ii) living donor (i.e. decision-making capacity, improved knowledge and comprehension of the short and long-term risks of living donation, diminished hesitancy) outcomes, and (iii) proportion of kidney transplants performed with a LD. Besides, to diminish the potential for inequities among more vulnerable groups (i.e. socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals, migrant and ethnic minority subjects, persons with lower health literacy levels and numeracy), it is necessary to determine whether tailored educational strategies may improve implementation of shared decision-making. Formal studies will also develop prompt question sheets and comprehension assessment tools and will assess their effectiveness to improve LD–physician partnership and LD understanding in LD programs. Research on these aspects is warranted in the near future.

Lucy is a 27-year-old woman who comes along to an educational session at the hospital with her husband, who has end-stage kidney disease. Here, they both learn about the possibility of living kidney donation. As a potential living kidney donor, she receives written information including a booklet (written in simple language and enriched with evidence-based tables and figures of the benefits and the short- and long-term risks of living donation), a prompt question sheet to empower her to ask relevant questions (according to her own values, life circumstances, goals and, when this is the case, informative gaps) at the following outpatient appointment, and contact information. Five weeks later, she contacts the hospital and is scheduled for an appointment with a nephrologist who provides her with additional information about the risks and benefits related to kidney donation, including the risks related to the evaluation process. She is informed that she should take some time before making the decision. A follow-up visit is not scheduled. She can contact the hospital if she is interested in proceeding with the evaluation. One month later, she contacts the hospital and schedules a follow-up consultation. Here, she states her wish to proceed with initial work-up. During this session, the initial information is repeated. However, now that she has been empowered, it is more of a dialogue, focused on questions and answers, and making sure that she has read and understood the written information. Then they proceed with the evaluation. During the evaluation period, she has contact information to a transplant nurse, and she is encouraged to ask questions as they arise. There are no pathological findings during the donor evaluation. She fills out a written comprehension assessment questionnaire to make sure that she has understood all of the risks related to the procedure and to identify potential gaps to be addressed prior to donation. The entire decision-making process is documented in her medical record and, before nephrectomy is performed, she finally signs a formal informed consent document.

Fred is 62-year-old man who is healthy, apart from having hypertension. His close friend John has end-stage kidney failure. Fred has read on the internet about the possibility of living donation. After telling his friend, he contacts the transplant center and asks if he can undergo evaluation as a potential kidney donor. A few weeks later, he has an appointment with a nurse specialist who screens him for diseases and teaches him about the evaluation and donation process. She gives him information about the short- and long-term risks and provides him with the corresponding written information (supplemented with figures and tables to improve understanding), and a prompt question sheet to identify potential areas which he wishes to address better, according to his own individual life circumstances, goals and level of understanding. He is not scheduled for a follow-up appointment but is asked to contact the transplant center at a later date, and not earlier than after 4 weeks. A few weeks later, he contacts the transplant center and reaffirms his wish to donate a kidney. A second appointment is scheduled with a nephrologist. They talk about the risks associated with donation and discuss the written information that he has previously received. Especially, they discuss donation-associated risks in relation to his pre-existing hypertension. They schedule a second visit, and the doctor refers him for biochemistry and measurement of renal function. He is given a phone number that he can call if he has any further questions or aspects he wishes to clarify. The second visit is 2 months later. At this time point, they discuss the different short- and long-term risks, and he completes a written comprehension assessment questionnaire with relevant knowledge items about the donation process. The questionnaire confirms complete understanding. As the evaluation process is finished, the whole decision-making process is documented in his medical record, and, before being referred to the transplant center, he signs an informed consent form. However, as the date of the surgery approaches, he has second thoughts and decides to withdraw. The team provides support to communicate his decision to John.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Gratitude goes out to Prof. Robert W. Steiner, Co-Director of Transplant Nephrology and Medical Director of Kidney & Pancreas Transplantation (UC San Diego Health) for the provision of the comprehension assessment questionnaire proposed in Supplementary data, Appendix C. The DESCaRTES Working Group is an official body of the ERA. M.C. was partially supported by INT21/00003 (Spanish Ministry of Health ISCIII FIS-FEDER).

FUNDING

The authors declare no funding.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation.

Comments