-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Amelia Fraser-McKelvie, Alfonso Aragón-Salamanca, Michael Merrifield, Martha Tabor, Mariangela Bernardi, Niv Drory, Taniya Parikh, Maria Argudo-Fernández, SDSS-IV MaNGA: the formation sequence of S0 galaxies, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 481, Issue 4, December 2018, Pages 5580–5591, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty2563

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gas stripping of spiral galaxies or mergers are thought to be the formation mechanisms of lenticular galaxies. In order to determine the conditions in which each scenario dominates, we derive stellar populations of both the bulge and disc regions of 279 lenticular galaxies in the MaNGA survey. We find a clear bimodality in stellar age and metallicity within the population of S0s and this is strongly correlated with stellar mass. Old and metal-rich bulges and discs belong to massive galaxies, and young and metal-poor bulges and discs are hosted by low-mass galaxies. From this we conclude that the bulges and discs are co-evolving. When the bulge and disc stellar ages are compared, we find that the bulge is almost always older than the disc for massive galaxies (M⋆ > 1010 M⊙). The opposite is true for lower mass galaxies. We conclude that we see two separate populations of lenticular galaxies. The old, massive, and metal-rich population possess bulges that are predominantly older than their discs, which we speculate may have been caused by morphological or inside-out quenching. In contrast, the less massive and more metal-poor population have bulges with more recent star formation than their discs. We postulate they may be undergoing bulge rejuvenation (or disc fading), or compaction. Environment does not play a distinct role in the properties of either population. Our findings give weight to the notion that while the faded spiral scenario likely formed low-mass S0s, other processes, such as mergers, may be responsible for high-mass S0s.

1 INTRODUCTION

The lenticular (or S0) morphology class introduced by Hubble (1926) contains galaxies that consist of a bulge and a disc, but lack spiral arms. A simple interpretation of the Dressler (1980) morphology–density relationship would imply that all lenticular galaxies were once spirals (de Vaucouleurs 1959; Sandage 1961; Dressler et al. 1997; Fasano et al. 2000; Desai et al. 2007). While all S0 galaxies appear morphologically similar, mounting evidence suggests that they encompass a wide range of formation processes and evolutionary pathways. Indeed, recent literature has revealed a range of photometric, spectroscopic, and kinematic properties in S0 galaxies (e.g. Laurikainen et al. 2010; Barway et al. 2013; Graham et al. 2018). From this, we conclude that lenticular galaxies may span a much wider range in galactic properties (and possibly formation pathways) than their relatively simple morphology would suggest.

The historical view that lenticulars form from faded spirals is supported by much prior literature (e.g. Bedregal, Aragón-Salamanca & Merrifield 2006; Moran et al. 2007; Laurikainen et al. 2010; Cappellari et al. 2011; Prochaska Chamberlain et al. 2011; Kormendy & Bender 2012; Johnston, Aragón-Salamanca & Merrifield 2014, and references within). In this scenario, gas within the spiral arms is either stripped through environmental mechanisms such as ram pressure stripping (Gunn & Gott 1972), harassment (Moore, Lake & Katz 1998), or strangulation (e.g. Larson, Tinsley & Caldwell 1980; Balogh, Navarro & Morris 2000), or the galaxy simply runs out of gas. What generally remains is a largely quiescent disc hosting a pseudo-bulge (Kormendy & Kennicutt 2004). This scenario has also been backed up with observations of spiral and S0 globular cluster number densities and specific frequencies (Aragón-Salamanca, Bedregal & Merrifield 2006; Barr et al. 2007), and simulations (Bekki & Couch 2011). Given that lenticulars are more populous in denser environmental regions (Dressler 1980; Postman & Geller 1984), this scenario could be used to describe the formation of the majority of lenticulars.

The faded spiral paradigm cannot explain S0s whose properties vary significantly from expected progenitor spirals however (e.g. Williams, Bureau & Cappellari 2010; Falcón-Barroso, Lyubenova & van de Ven 2015). In addition, recent literature has hinted at disparate bulge stellar populations within lenticulars (e.g. Johnston et al. 2014; Mishra, Barway & Wadadekar 2017; Tabor et al. 2017), often concluding that late-type spirals could not have plausibly evolved into the S0s we see today (e.g. Christlein & Zabludoff 2004; Burstein et al. 2005; Gao et al. 2018).

A growing body of literature suggests that major mergers can also form S0 galaxies (e.g. Spitzer & Baade 1951; Tapia et al. 2017; Diaz et al. 2018; Eliche-Moral et al. 2018; Méndez-Abreu et al. 2018). In this scenario, merger activity builds a bulge, and an inside-out formation scenario accretes gas on to a rotating disc. This sequence of events ensures that the bulge and disc possess separate formation histories, though simulations have also shown that it is possible to retain some degree of bulge and disc coupling throughout major merger events (Querejeta et al. 2015). Simulations also exist that create S0s by the fragmentation of an isolated, unstable cold disc over a short time-scale (Saha & Cortesi 2018).

Internal secular evolution may also be involved in S0 formation (e.g. Laurikainen et al. 2006). Optically red spiral galaxies have bar fractions of 70–80 per cent (Masters et al. 2010; Fraser-McKelvie et al. 2018); these morphological features may be involved in the quenching of galaxies, funnelling gas towards the centre, inducing starbursts and bulge growth in these transition objects (e.g. Combes & Sanders 1981; Pfenniger & Norman 1990).

Whatever the formation mechanism, the overarching differentiator in lenticular structural relations seems to be luminosity (Barway et al. 2005; Aguerri 2012). Many studies describe two separate populations of lenticular galaxies, one of which is luminous, with high bulge fractions and classical-type bulges, while the second fainter population contains less bulge-dominated galaxies and pseudo-bulges (e.g. Barway et al. 2007, 2009). These trends hold irrespective of environment (Barway et al. 2005). From this, it can be inferred that the rapid collapse scenarios required to produce classical bulges are produced by entirely different mechanisms to those creating the pseudo-bulges. This might be explained by the fainter lenticulars being faded spiral descendants, and the more luminous S0s having had their stellar populations in place at high |$z$|, the classical bulge perhaps being created by repeated mergers (e.g. Barway et al. 2013). Furthermore, classical bulge-hosting lenticulars tend to contain old stellar populations, while pseudo-bulge-hosting galaxies can still show signs of recent or even current star formation.

While this is a convenient argument, recent studies have placed pseudo-bulge-hosting lenticulars at both ends of the optical colour spectrum (Mishra et al. 2017). The merger formation scenario may also not be required if classical bulge-hosting spirals evolve preferentially into S0s, as suggested by Mishra, Wadadekar & Barway (2018). Irrespective of S0 formation mechanism, it seems that lenticulars cannot be separated by bulge type alone.

Stellar populations can vary dramatically across a galaxy, and it is becoming increasingly commonplace to analyse individual components of a galaxy separately (e.g. Johnston et al. 2014; Tabor et al. 2017; Coccato et al. 2018; Rizzo, Fraternali & Iorio 2018). Bulge-disc decomposition is frequently employed as an analysis technique as it allows the separation of dispersion-dominated bulge light of a galaxy from the rotationally supported disc regions. The advent of large-scale galaxy integral field spectroscopy (IFS) surveys such as Mapping Nearby Galaxies at APO (MaNGA; Bundy et al. 2015) provides spatial information on thousands of nearby galaxies, from which stellar population information for various galaxy components may be derived.

This work aims to utilize the large sample of lenticular galaxies covering a wide mass range within the MaNGA survey. We will probe the formation sequence of S0 galaxies by comparing the stellar populations of their bulge and disc regions. From this we will infer likely formation scenarios, and the dependence of different galaxy component evolutionary histories on one another. This paper is organised as follows: in Section 2 we describe the MaNGA survey and data products, along with our lenticular selection technique. In Section 3, we present line index and derived age and metallicity measurements for the bulge and disc regions of MaNGA lenticulars, then we discuss possible formation scenarios, comparing to the results of previous literature. In Section 4, we summarize our findings.

2 DATA

Lenticular galaxies were selected from the MaNGA survey’s MaNGA product launch 5 (MPL-5), consisting of 2778 galaxy data cubes observed from March 2014 to May 2016.

2.1 The MaNGA survey

The MaNGA galaxy survey is an IFS survey that aims to observe ∼10 000 galaxies by 2020 (Bundy et al. 2015; Drory et al. 2015) and is a project of SDSS-IV (Blanton et al. 2017) using the 2.5 m telescope at the Apache Point Observatory (Gunn et al. 2006) and BOSS spectrographs (Smee et al. 2013). The survey was designed to observe a luminosity-dependent sample of galaxies above a stellar mass of |$10^{9}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|, with a roughly flat log (M⋆) distribution (Law et al. 2015; Wake et al. 2017). Because of the log (M⋆) distribution criterion, more high-mass, red galaxies are observed than is expected for a representative sample of the local Universe. Each galaxy is therefore also assigned a weighting, which upweights or downweights a galaxy according to how under- or overrepresented it is in the MaNGA sample. We may then consider the weighted sample to be volume-limited, and appropriate for statistical analysis. A ‘Primary’ sample of galaxies (50 per cent of targets) is defined with homogeneous spatial coverage out to ∼1.5 Re, (where Re is the Petrosian half-light radius in the r band), with the addition of a ‘Colour-Enhanced’ sample (∼17 per cent of sample) to balance the colour distribution at fixed M⋆ (Bundy et al. 2015). Combined together, the Primary and Colour-Enhanced samples (termed the ‘Primary+’ sample), make up |$67{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$| of the MaNGA targets, the remaining |$33{{\ \rm per\ cent}}$| of which comprise the ‘Secondary’ sample of galaxies with extended coverage out to ∼2.5Re.

All galaxy observations have wavelength coverage of ∼3500–10 000 Å, spectral resolution R ∼2000 (which gives an instrumental resolution of ∼60 km s−1), and an effective spatial resolution of 2.5 arcsec (full width at half-maximum) after combining dithered observations; the sample lies within the redshift range 0.01 < |$z$| < 0.15 (Yan et al. 2016b). Observations are reduced by a data reduction pipeline (Law et al. 2016; Yan et al. 2016a) and made available as a single data cube per galaxy.

2.2 Lenticular Galaxy selection

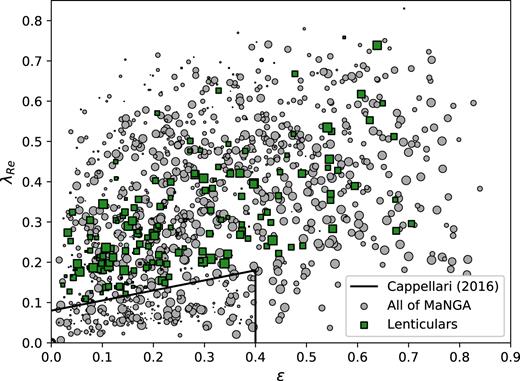

(λRe, ε) diagram of both all of the galaxies in MPL-5 (grey points), and the regularly rotating lenticulars selected for this study (green). Data points are scaled by their volume weighting in the MPL-5 Primary+ sample. The slow rotator region, as defined by Cappellari (2016), is denoted by a black line. The lenticulars in our sample are spread across the regularly rotating area of (λRe, ε) space with no slow rotators, a consequence of our kinematic selection criterion.

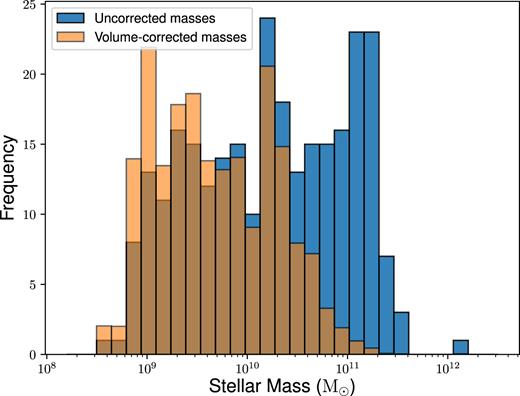

By construction, the volume weighting also has the effect of taking MaNGA’s approximately flat log (M⋆) distribution, and weighting the lower mass galaxies in such a way that the mass distribution begins to resemble the true mass function expected for the local Universe. Fig. 2 shows a histogram of the mass distribution both before (blue) and after (orange) the volume weighting is applied to the sample. It should be noted that this sample spans a mass range of several dex.

Histograms of the mass distribution of the lenticular sample before (blue) and after (orange) volume-weighting. The relatively flat log (M⋆) distribution transforms to look more like a typical, local Universe mass function with the volume weightings provided for the Primary+ sample.

2.3 Bulge and disc measurements

In order to disentangle the effects of various galaxy components from one another, we separate the MaNGA data cubes into bulge and disc regions. We use the catalogue of Simard et al. (2011), who performed photometric bulge + disc decomposition on SDSS data release seven galaxies. This catalogue provides fits to the images that allow the bulge Sérsic index to vary freely based on the light profile of the galaxy, or constrain it such that nb = 4. We check the F-test probabilities from the Simard et al. (2011) catalogue to determine the best model to use for our data. When the nb = 4 bulge + disc and free nb bulge + disc models are compared, we find that the majority (66 per cent) of the lenticular sample are best fit using a free nb bulge + disc model, hence, this is what we use for our sample. We have compared the r-band effective radius measurements for both fitting schemes and find general agreement in the photometric parameters of the fits over the sample. However, we note that the nb = 4 fits overestimate the bulge effective radius for galaxies where a more peaked bulge light distribution is favoured. Nevertheless, there is good agreement between the reported bulge to total ratios (B/T) for each technique. We therefore use the free nb models to characterise the bulge profiles in our sample. Bulge effective radius (Rb), nb, B/T, and axis ratio (b/a) measurements are included in Table A1.

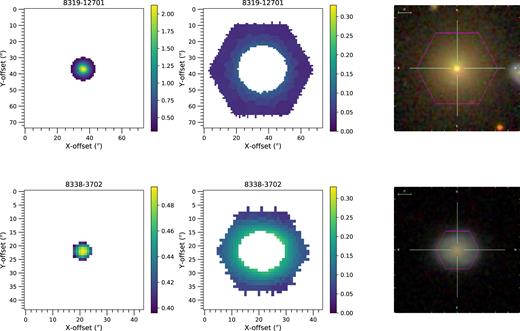

We define bulge regions to include all spaxels within one bulge effective radius of the central spaxel of a given galaxy, while disc regions are defined as spaxels outside two bulge effective radii and within the MaNGA field of view. Fig. 3 shows examples of the bulge and disc decompositions for two lenticulars in the sample, one high-mass, and one low-mass.

The bulge (left) and disc (centre) regions of two MaNGA lenticulars, 8319-12701 (|${M}_{\star }=9.6\times 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|) and 8338-3702 (|${M}_{\star }=1.6\times 10^{9}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|). Bulge regions are defined as all spaxels within one Rb, and disc as spaxels outside 2 Rb. The bulge and disc regions are coloured by the relative flux contribution of each Voronoi bin to the total flux of the galaxy. The right shows the colour images of the galaxy with the hexagonal MaNGA field of view overlaid in pink.

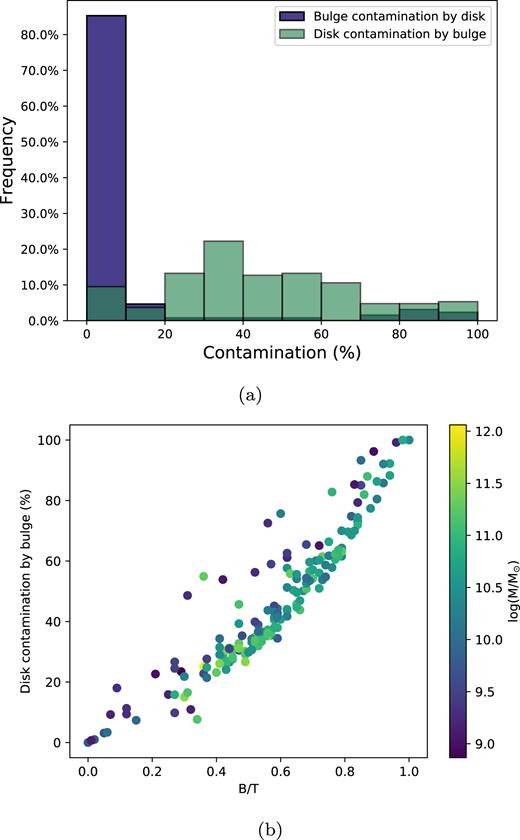

In order to quantify any contamination occurring in either component as a result of the other, we calculate the fraction of disc light contaminating the bulge and bulge light contaminating the disc for every galaxy in our sample in Fig. 4(a). We use the Simard et al. (2011) values for nb, Rb, and disc scale length (h) to compute bulge and disc light profiles, then calculate the fraction of bulge flux compared to total flux within one bulge effective radius for the bulge regions, and between two bulge effective radii and 1.5 Re for the disc regions. Rather than integrating to infinity, 1.5 Re was used as the edge of the disc as it is the target radius for the MaNGA Primary+ sample (Bundy et al. 2015).

Quantification of the contamination of light within regions defined for each galaxy in the S0 sample. In panel (a) we plot histograms of the fraction of contamination by the disc in the bulge regions (blue), and the bulge in the disc regions (green). While there is negligible contamination by the disc within bulge regions, some discs do have significant contamination of bulge light. In panel (b) we plot the disc contamination by the bulge as a function of the B/T, with points coloured by stellar mass. As expected, contamination within the disc correlates with B/T. We discuss the possible effects of this contamination on our results in the text.

While there is negligible disc light contamination in all bulge regions, for some of the larger B/T galaxies we do observe a proportion of bulge light contributing to the disc region. In Fig. 4(b), we plot the disc contamination by the bulge as a function of B/T, and colour data points by stellar mass. As expected, the fraction of disc contamination correlates with B/T. There are no systematic trends in B/T with stellar mass, though for a given B/T, the discs of lower mass galaxies will generally be more contaminated than their higher mass counterparts. We will investigate the effects of this bulge light contamination within disc regions on stellar population trends observed below.

For every galaxy in the sample, we measure the light-weighted average of the Lick indices H β, Mgb, Fe5270, and Fe5335 (as defined by Worthey et al. 1994), on MaNGA data which has been spatially Voronoi binned using the method of Cappellari & Copin (2003) to a signal to noise ratio of 10 per bin. We use the velocity dispersion-corrected index measurements provided by the MaNGA firefly value-added catalogue (Abolfathi et al. 2017), which builds on the MaNGA data analysis pipeline (DAP; Westfall et al., in preparation). These Lick indices have been corrected to MaNGA’s spectral resolution using the stellar population models of Maraston & Strömbäck (2011) and are measured from emission line subtracted spectra. The procedure for absorption line fitting is fully described in Section 2.3 of Parikh et al. (2018), but the basic recipe is to firstly fit and subtract emission lines from the spectrum using tools from the MaNGA DAP. The emission line-free spectrum is then used as input into the firefly code, which determines the age and metallicity of the spectrum. The M11-MILES SSP combination closest to the age and metallicity derived from the full spectrum fitting from firefly is then obtained. Then, the indices are measured on the model convolved to the wavelength-dependent SDSS resolution and convolved to the velocity dispersion of the spectrum as provided by the DAP. The ratio between these two measurements is the factor applied to the index measurements to correct them to the SDSS resolution. We obtain the light-weighted average of these indices in all spaxels in the designated bulge and disc regions for all galaxies in the sample apart from MaNGA galaxy 8931-12705, which on closer inspection contains two separate galaxies in the field of view.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 H β–[MgFe]′ and age–metallicity realtions

![Observables and their implied physical stellar ages and metallicities for the bulge (panels a and b) and disc (panels c and d) regions of MaNGA lenticulars. The index–index diagram for the bulge regions is shown in panel a, and disc regions in panel c, with SSP model predictions of Vazdekis et al. (2010) also overlaid. These model lines are bi-linearly interpolated between to obtain stellar age and metallicity estimates for the bulge (panel b) and disc (panel d) regions. An arbitrary dashed line separates the two regions of more metal-rich, older stellar populations from the metal-poor, younger populations. For all plots, the data points and contours are weighted by their volume weighting in the Primary+ sample, and points are colour-coded by their NSA stellar mass. Representative error bars derived from Monte Carlo errors on the Lick index measurements are also displayed. The contours show a clear bimodality in H β and [MgFe]′, and age and metallicity for both the bulge and disc regions of the MaNGA lenticulars. This trend correlates strongly with stellar mass.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/mnras/481/4/10.1093_mnras_sty2563/1/m_sty2563fig5.jpeg?Expires=1749884946&Signature=PmgdNqshpbaaZG-Ran-dWTHSLGYzP0FC0inC4CNkWi5KdUZQOtLWdP8Ga~zZlkzTxtoTG0x8OfiwwtGoe~4fL8kz-5CY1htlI~Y1oFN12dIoLGuiY5OcrCyTUIyXhDb73vJuGzrmP-wK2jZXMPXSHDIesQi71IuSpE8bPahnmJ5X940cF9eJa~piDaP1KEsrvDWiUayLVj8~q3T23KvkNncNrHpZCimRuGokq~r-2-G-lo7r9-31u0u2dCrUZrw8impvYrgv2U6XHDfywwQ0KQ82KmxCUWN~xLiVNV8vG5z85GOpy7Pg0zshotnTtb75xYfSXvzE10xTCTBwKkyvYw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Observables and their implied physical stellar ages and metallicities for the bulge (panels a and b) and disc (panels c and d) regions of MaNGA lenticulars. The index–index diagram for the bulge regions is shown in panel a, and disc regions in panel c, with SSP model predictions of Vazdekis et al. (2010) also overlaid. These model lines are bi-linearly interpolated between to obtain stellar age and metallicity estimates for the bulge (panel b) and disc (panel d) regions. An arbitrary dashed line separates the two regions of more metal-rich, older stellar populations from the metal-poor, younger populations. For all plots, the data points and contours are weighted by their volume weighting in the Primary+ sample, and points are colour-coded by their NSA stellar mass. Representative error bars derived from Monte Carlo errors on the Lick index measurements are also displayed. The contours show a clear bimodality in H β and [MgFe]′, and age and metallicity for both the bulge and disc regions of the MaNGA lenticulars. This trend correlates strongly with stellar mass.

Overlaid on the index–index plots are the single stellar population (SSP) model predictions of Vazdekis et al. (2010) using Padova 2000 isochrones and a Chabrier (2003) initial mass function. Data points are scaled by their volume weighting in the Primary+ sample, and coloured by their stellar mass, which is taken from the NASA Sloan Atlas (NSA),1 calculated using the photometric sky subtraction technique of Blanton et al. (2011). Monte Carlo-based errors on the line measurements were derived by perturbing the flux at each wavelength using the error in the flux derived by the MaNGA DAP for 100 realizations. The weighted contours show a clear bimodality in H β and [MgFe]′ for both the bulge and disc regions, and are well correlated with stellar mass. The bulge and disc H β, Mgb, Fe5270, and Fe5335 measurements for each galaxy are listed in Table A2.

To obtain estimates of bulge and disc stellar age and metallicity, we translate these measurements into physical properties by bi-linearly interpolating between the quadrilaterals formed by the SSP model lines. Where any data point lay outside of the model grid lines, we assigned it the age or metallicity of the nearest grid line. We note that while this method is a simplification, especially when compared to full spectral fitting models, it is closer to the actual data. Given the difficulties in obtaining robust star formation histories, along with their degeneracies and non-uniqueness (see Wilkinson et al. 2017, for a summary), this simple method is more robust for relative comparisons between derived ages and metallicities.

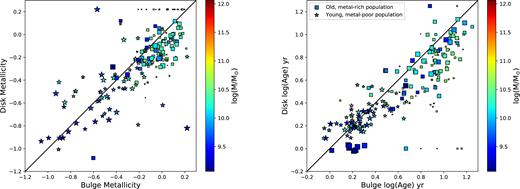

In Fig. 5, we plot the bulge (panel b) and disc (panel d) derived stellar ages and metallicities, again with data points scaled by their volume weighting in the MaNGA Primary+ sample and coloured by stellar mass. We see two clear populations of lenticulars – one that is metal rich with an old stellar population and high stellar masses, and the other that comprises a younger stellar population, and is more metal poor. We separate these populations by an arbitrary dashed line, chosen to distinguish between the two separate populations as well as possible. Trends in bulge and disc age and metallicity are more clearly seen in Fig. 6, where bulge metallicity is plotted against disc metallicity, and bulge age against disc age. Galaxies that are old, metal rich with high stellar mass that are located above the dividing line of Fig. 5 are shown with square markers, and those below the dividing line are shown with star-shaped markers. Again, we see the bulges of higher mass S0s are almost always older and more metal rich than their discs. Given that from Fig. 4(b), we see the fraction of disc contamination by the bulge seems to be insensitive to stellar mass, we confirm that any trends seen are not an effect of bulge contamination as a function of mass.

Comparison of bulge and disc metallicities (left) and ages (right) for MaNGA lenticulars. Each point is coloured by its stellar mass and weighted by its volume weighting in the Primary+ sample, and galaxies that are located above the dividing line of Fig. 5(b) (predominantly old and metal-rich) are shown with square markers. Those below the dividing line are shown in star markers. In both panels there is a 1:1 line for comparison, and we see that on average, bulge and disc ages and metallicities are similar within a given galaxy. The bulges of higher mass S0s are systematically older and more metal rich than their discs.

Interestingly, in Fig. 6, we see the high-mass galaxies that are dominated by metal-rich, old stellar populations in their core also possess similar stellar populations in their disc (albeit slightly younger and more metal-poor). High-mass lenticulars almost exclusively host older and more metal-rich bulges and discs than their lower mass counterparts. We conclude from this that the bulges and discs of lenticulars, at least to some degree, are co-evolving (e.g. Balcells & Peletier 1994; Laurikainen et al. 2010).

When we divide the two populations by the arbitrary dashed line shown in Fig. 5(b) and (d), the separation in mass between these two populations corresponds to lenticulars of stellar mass |${\lesssim } 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|. We note this is a similar mass to that reported by Tasca et al. (2009) (|${\sim }6\times 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|), above which spirals are less likely to evolve, irrespective of their environment. If spirals are less likely to evolve, this may be further evidence that high-mass lenticulars formed from mechanisms other than spiral disc fading, for example, dissipational processes.

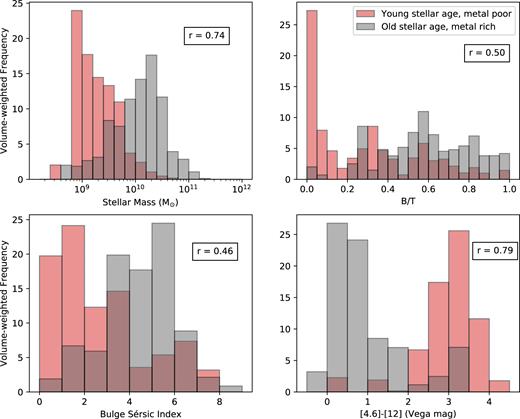

We investigate trends in physical properties for these two populations of lenticulars in Fig. 7 by separating the lenticular population into two sub-samples, defined by which side of the dividing line of Fig. 5(b) they inhabit. While there is a clear division in stellar mass between the older, metal-rich population and the younger, metal-poor lenticulars, we also see strong correlations in bulge Sérsic index and Wide-Field Survey Explorer (WISE) mid-infrared (mid-IR) colour. Bulge Sérsic indices are obtained from the Simard et al. (2011) catalogue, and we see that a large proportion of young metal-poor lenticulars possess bulges of Sérsic index nb < 2, and nearly all old, metal-rich lenticulars have nb > 2. This suggests that pseudo-bulges may be more prevalent in the young, metal-poor population, and classical bulges in the older, metal-rich population, which in turn, adds further support to the separate formation mechanisms scenario (e.g. Fisher & Drory 2008, 2016). The correlation with nb is weaker than with stellar mass, shown by the correlation coefficient, r, between each property and the distance of each galaxy to the dividing line, shown in Fig. 7, where a coefficient of r = 1 corresponds to a perfect correlation between two quantities.

Histograms of physical properties of both the older, more metal-rich sample of lenticulars (grey), and the younger, more metal-poor sample (red). These populations are defined by considering the bulge age and metallicity with respect to the dividing line of Fig. 5(b). From top left: stellar masses, B/T, bulge Sérsic index, and WISE 4.6–12 μm colour. All properties show a somewhat bimodal distribution, with the exception perhaps of B/T. Correlation coefficients, r, between each quantity and the distance from each galaxy to the arbitrary separating line drawn in Fig. 5(b) are also printed. WISE 4.6–12 μm and stellar mass possess the strongest correlations.

WISE 4.3–12 μm colour is an excellent indicator of recent star formation activity (Jarrett et al. 2011; Cluver et al. 2014), and we see a very obvious division in this quantity between the two lenticular populations in Fig. 7. The more passive mid-IR colours of the older and more metal-rich population indicate they have likely stopped forming stars, while the younger, more metal-poor population possess mid-IR colours consistent with recent star formation, possibly through a rejuvenation scenario. The only physical quantity that does not possess a strong bimodality is B/T. There are many galaxies that are metal poor with younger stellar populations but large B/T. From this, we infer that it is stellar mass, and not B/T, that drives the division in lenticular stellar populations.

The striking bimodality in both stellar age and metallicity by stellar mass (and, presumably, luminosity) agrees well with the work of Barway et al. (2007, 2009), who propose that less luminous lenticulars have been formed by secular processes gently stripping gas from spiral discs, and the more luminous S0s have been formed at high redshift by violent, dissipative processes. Fainter samples such as those presented in Bedregal et al. (2006) still have young and metal-poor stellar populations, which we would expect from discs possessing pseudo-bulges. Works that study only high-mass lenticulars, such as Méndez-Abreu et al. (2018), conclude that high-mass lenticulars were likely formed by dissipational processes such as major mergers or gas accretion at high redshift. From this it is possible to conclude that the formation pathway taken by a lenticular may chiefly be determined by its mass, and in this study which spans a wide range of masses we see clear evidence of these multiple pathways.

3.2 |$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$|–Mgb and α-element abundances

The Lick indices Mgb and |$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$|, (where |$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$| is defined as |$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle = (\textrm{Fe}5270 +\, \textrm{Fe}5335)/2$|), are a good probe of α-element abundances, which indicate the time-scale of star formation. Type II supernovae eject α-element-rich material shortly after star formation has commenced. In contrast, Type Ia supernovae are the product of older stars, and contribute only small amounts of α-elements when they explode. Instead, they tend to enrich the interstellar medium with Fe. Hence, massive early-type galaxies typically exhibit enhanced α-abundance ratios (e.g. Thomas et al. 2005), thought to be a result of active galactic nucleus feedback suppressing star formation at early times (e.g. Segers et al. 2016). Without this early truncation of star formation, lower mass galaxies may retain star formation over longer time-scales and host more Type Ia supernovae, which we should observe as a lower α-enhancement.

In Fig. 8, we plot the bulge and disc |$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$| and Mgb indices for the sample of lenticular galaxies, again colour-coded by stellar mass with point size and contours weighted by a galaxy’s over- or underrepresentation in the MaNGA sample. These values are also recorded in Table A2. The high-resolution stellar population models of Thomas et al. (2011) are overlaid for a model age of 10 Gyr (solid lines) and 2 Gyr (dashed lines). While differences in bulge and disc metallicity are seen in panels a and b, there seems to be little difference in α-abundance between the bulge and the disc. Panel c confirms this, as we plot bulge and disc Mgb/|$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$|. The similarity in bulge and disc α-enhancement regardless of galaxy mass or B/T leads us to believe that bulge contamination is not affecting the α-enhancement measurements of the lenticular sample.

![Investigation into the α-enhancement of the S0 population. Bulge (panel a) and disc (panel b) Mgb and $\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$ measurements are presented with Thomas, Maraston & Johansson (2011) high-resolution SSP models overlaid for 10 Gyr (solid) and 2 Gyr (dashed) models. The data points are again weighted by their volume weighting in the Primary+ sample, and points are colour-coded by their stellar mass with representative error bars in the corner. The average [α/Fe] is ∼0.3 for the entire S0 sample in both the bulge and disc regions, and observed trends in the Mgb and Fe indices are hence the result of metallicity differences between the bulge and disc. In panel c we plot bulge versus disc Mgb/$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$ and see the α-enhancement for bulge and disc is very similar at all masses.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/mnras/481/4/10.1093_mnras_sty2563/1/m_sty2563fig8.jpeg?Expires=1749884946&Signature=4xCxil4r1yQsi5uG4im6Xry8nXAP28tNOX7KUj6G9HcAxm6PmG6GTJNcRDMAtx7cJLyfOHXYGCwdtZHEJf16ur~M32DSGpTHWSbhLRsjWMNVcOywS8abDZXVdM3mEBPVr-XHtUTm-PJKybTfEzcdPZNKMsPjp52kCo8YlwINEe9vbfzH1NKoyQMhGPwlNDWBs8tbcETw--n2SMKqrl~whnSdPRuwhG~v7sf7g2suBQqJEM-j9yWKFO1VIUjXZA83P4GuFHD0hB86dAtPFR-3-Yc5ib7gol~fjPEK5AacddYX4IiGUPlJyqPYZqSixE-ZTxWozfFuy~B98EdJ4w5VKg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Investigation into the α-enhancement of the S0 population. Bulge (panel a) and disc (panel b) Mgb and |$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$| measurements are presented with Thomas, Maraston & Johansson (2011) high-resolution SSP models overlaid for 10 Gyr (solid) and 2 Gyr (dashed) models. The data points are again weighted by their volume weighting in the Primary+ sample, and points are colour-coded by their stellar mass with representative error bars in the corner. The average [α/Fe] is ∼0.3 for the entire S0 sample in both the bulge and disc regions, and observed trends in the Mgb and Fe indices are hence the result of metallicity differences between the bulge and disc. In panel c we plot bulge versus disc Mgb/|$\langle \, \textrm{Fe} \rangle$| and see the α-enhancement for bulge and disc is very similar at all masses.

The majority of lenticulars possess bulge and disc α-enhancement above Solar values, with an average [α/Fe]∼0.3. If the Milky Way is considered a typical spiral galaxy, then the time-scale for star formation for nearly all S0 galaxies is shorter than for spirals. This trend in α-enhancement is seen regardless of S0 stellar mass or implied formation mechanism; S0s all quenched similarly quicker than the Milky Way. We observe the α-enhancement for the low-mass galaxies is more spread than that of the high-mass galaxies, indicating that star formation time-scales are more varied for low-mass galaxies. We infer that low-mass galaxies are more fragile than their high-mass counterparts, and may be more significantly impacted by environmental trends (e.g. Maltby et al. 2010; Fraser-McKelvie et al. 2018), providing a wider variety of star formation histories.

Johnston et al. (2014) found that the discs of Virgo cluster S0s (all with NSA stellar masses |$\lt 4\times 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|) were slightly more α-enhanced than the bulges. This implies the star formation time-scales of discs are shorter than within the bulges; they presented a scenario wherein the gas that produced the final star formation event in the bulge was pre-enriched by earlier star formation in the disc. They suggest this may have occurred as gas was dumped into the core of a galaxy after a stripping event. This same event may have quenched the disc and transformed spiral morphology to lenticular. We do not observe this trend, and also note that we have no cluster S0s in our sample. It is possible this effect is a cluster-only phenomenon, and further work on lenticulars with a wide range of masses living in varied environments is required.

3.3 Environment

In order to determine whether galaxy large-scale environment is having an effect on stellar populations within S0 galaxies, we present two different environmental indicators: the tidal strength parameter, Qlss, and the projected galaxy number density, ηk. These quantities are defined in Argudo-Fernández et al. (2015), and briefly summarized here. The tidal strength parameter, Qlss, is an estimation of the local tidal strength at 1 Mpc, and gives an indication of how strongly nearby galaxies are perturbing the galaxy in question. The greater the value of Qlss, the less isolated the galaxy is from external influence. ηk is the projected density to the 5th nearest neighbour. It is well correlated with the distance to the 5th nearest neighbour, such that galaxies with a greater distance to their 5th nearest neighbour will have low values of ηk.

In Fig. 9, we present bulge [MgFe]′ and H β measurements as a function of the environmental measures Qlss and ηk. Galaxies within structure are indicated with square coloured markers, and those deemed isolated by the method of Argudo-Fernández et al. (2015) are shown as grey triangles. We see a range of environments across the entire H β/[MgFe]′ space, with both isolated S0s and those within denser regions or with tidal perturbations seen for all stellar masses, ages, and metallicities. From this we conclude that neither nearby neighbours perturbing S0s nor large-scale structure is singularly responsible for either population of S0s. The environmental parameters Qlss and ηk are listed for each galaxy in Table A1.

![The environments of MaNGA lenticular galaxies, as described by parameters introduced in Argudo-Fernández et al. (2015). Bulge H β, [MgFe]′, models, and errors are the same as for Fig. 5(a). S0s located in structure are denoted by squares, coloured by the environmental parameters Qlss (left) and ηk (right). Squares are sized by their weighting within the MaNGA sample, and contours show this weighted distribution. Isolated S0s are denoted by grey triangles. There is no obvious environmental dependence on MaNGA lenticular stellar populations.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/mnras/481/4/10.1093_mnras_sty2563/1/m_sty2563fig9.jpeg?Expires=1749884946&Signature=bZcLCW1Zwz1U17bLMxip26X5PCZE2veTe20th8Of14FdOMvjK35rkY6oCsPfskomcklx-BhcYecNqstYsRwh8kweh-gOslW6GEobSJuCIbLB8saN94Pl3qHfEY4EywrcVNCpAJfY~m1nzpfqMH~K7cl4qMvL3h1nV3oUmm0ngp7ggO17-Hz1bmNBhHvVx1BuQaSKPnbiSZZQuDF8Nn0hoZ6y4oqibpdqNJOthiTGBrPvzSjN6-fYa2HmtDk0qr5cpvmFwRvcBq89Rh1eN6728tu7FnLW-1B~d7YkEup5xVc8LYBjw3hci8h-8bFKXnJFm2ALR~Jgy90JFN0H2D~zcA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

The environments of MaNGA lenticular galaxies, as described by parameters introduced in Argudo-Fernández et al. (2015). Bulge H β, [MgFe]′, models, and errors are the same as for Fig. 5(a). S0s located in structure are denoted by squares, coloured by the environmental parameters Qlss (left) and ηk (right). Squares are sized by their weighting within the MaNGA sample, and contours show this weighted distribution. Isolated S0s are denoted by grey triangles. There is no obvious environmental dependence on MaNGA lenticular stellar populations.

The caveat to this environmental investigation is that, while the MaNGA galaxy sample contains galaxies from a wide range of environments, there are no nearby cluster S0s currently included in the sample. While these environments are statistically rare, the lenticulars within them are well studied (e.g. Kuntschner 2000; Barway et al. 2009; Bedregal et al. 2011). While somewhat concordant views on the star formation and stellar ages of bulges and discs of cluster S0s have been presented in the past (e.g. Sil’chenko 2006; Hudson et al. 2010; Johnston et al. 2014), we cannot comment on whether this extreme environment will strongly affect stellar population trends seen throughout lower density environments in the MaNGA sample.

3.4 Formation/quenching pathways

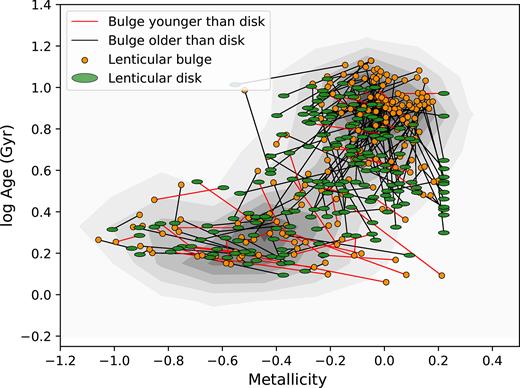

To investigate trends in bulge and disc age and metallicity further, we present the stellar population parameters for both galaxy components on the same plot in Fig. 10. For each galaxy, the bulge age and metallicity measurement is joined to its corresponding disc value by a line. The line is black if the bulge is older than the disc and red if the bulge is younger than the disc. We immediately see the majority of high-mass, old, and metal-rich lenticulars possess bulges that are older than their discs, while the bulk of young, metal-poor and lower mass lenticulars host bulges that are younger than their discs. The reversal of the older component between high-mass and some low-mass lenticulars gives further weight to a scenario in which two separate formation mechanisms are responsible for the overall lenticular population. Of the galaxies in the high-mass, metal-rich and older sample defined in Fig. 5(b), 84.7 per cent of galaxies possess bulges that are older than their discs. For the low-mass, metal-poor, and younger S0 sample, 50.8 per cent of galaxies possess bulges that are younger than their discs, though low-mass galaxies comprise 78.8 per cent of all galaxies with bulges younger than their discs in the entire S0 sample.

Bulge and disc stellar age and metallicity measurements for all MaNGA lenticulars. Here the bulge (orange) and disc (green) of a given galaxy are joined by a line. The line is black if the bulge of the galaxy is older than the disc, and red if the bulge is younger than the disc. Weighted contours are for the bulge regions. We see that the majority of galaxies with younger bulges lie in the low-mass, young, and metal-poor region of this diagram.

In Fig. 10, we see that the majority of old, metal-rich and massive lenticular galaxies possess bulges that are older than their discs. This, coupled with passive mid-IR colours, is consistent with the concept of morphological quenching. Martig et al. (2009) explain that the growth of a galaxy’s bulge (for example, through repeated mergers) will make the disc stable against fragmentation, quenching star formation. Indeed, the majority of high-mass lenticulars in this sample possess stellar populations >5 Gyr old. The older stellar population within the bulge implies the core quenched first, consistent with an inside-out quenching scenar(e.g. Mendel et al. 2013; Tacchella et al. 2015; Ellison et al. 2018; Spindler et al. 2018)

In contrast, many young, metal-poor, and low-mass lenticulars contain bulges that are younger than their discs. This is in line with simulations of spiral striping scenarios of Bekki & Couch (2011). We postulate that while the higher mass galaxies may have built up bulges large enough to undergo morphological quenching, this has not occurred in the low-mass galaxies. Instead, they may have undergone gas accretion processes, rejuvenating their bulges and causing a burst of recent (or current) star formation (e.g. Thomas & Davies 2006, in spiral galaxy bulges). This is in line with a ‘compaction’ scenario, in which an episode of gas inflow is triggered by gas-rich (mostly minor) mergers Johnston et al. (e.g. 2014), Zolotov et al. (2015), and Tacchella et al. (2016). From Fig. 10, we see the population of S0s with bulges younger than their discs has a much smaller variation in difference in bulge and disc stellar age when compared to the population of S0s with bulges older than their discs. This is consistent with a downsizing argument whereby more massive galaxies (those with bulges older than their discs) have formed their stars earlier and over a shorter timespan (e.g. Thomas et al. 2005). The majority of low-mass S0s also possess bulge Sérsic indices <2, indicating the population is dominated by pseudo-bulges (Fisher & Drory 2008). We expect these bulges will be preferentially formed via secular processes as opposed to violent, high-redshift mergers. This secular formation scenario for low-mass S0s supports findings such as those of Bellstedt et al. (2017), who find from simulations that low-mass S0s more closely resemble spiral progenitors than merger remnants.

We conclude that a scenario in which many low-mass S0s are formed by environmental stripping mechanisms, and high-mass systems are created by either morphological mechanisms or high-redshift dissipational processes, best fits the results of this study.

4 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

To investigate the stellar populations of the bulge and disc regions of lenticular galaxies, we examine a carefully selected sample of 279 S0 galaxies with a wide range of stellar masses from the MaNGA survey. We measure H β, Mgb, Fe5270, and Fe5335 Lick indices from which we infer light-weighted stellar age, metallicity, and α-enhancement parameters from both the bulge and disc regions of all galaxies in the lenticular sample. Despite some bulge light contamination within disc regions of high-mass S0s, we find:

A bimodal age and metallicity distribution in both the bulge and disc regions of S0s. This bimodal distribution correlates best with stellar mass, such that low-mass lenticulars possess young and metal-poor stellar populations in both their bulges and discs, and high-mass lenticulars are old and metal-rich across the entire galaxy. From this we may infer that two separate formation sequences are responsible for the populations observed – plausibly a stripped spiral scenario for the lower mass galaxies, and mergers or other high-redshift dissipational processes for the higher-mass lenticulars. These two separate populations are not correlated with environment, however.

Despite differences in bulge and disc age between individual galaxies, the structural components of high-mass lenticulars are on average older and more metal-rich than their lower mass counterparts. From this we conclude that galaxy bulges and discs evolve concurrently, with their formation histories and quenching pathways linked.

When we examine the age differences between individual galaxies, we find that lower mass lenticulars tend to have bulges that are marginally younger than their discs, whereas the opposite is true of high-mass galaxies. The high-mass galaxies can have quite an age difference between their old bulges and comparatively younger discs, but have mostly old stellar populations, from which we conclude high-mass lenticulars quenched inside-out, perhaps through a morphological quenching process.

Lower mass galaxies are likely to have nb <2, from which we imply either environmental mechanisms have stripped fuel for star formation, or the disc has simply run out of gas, fading the spiral arms. These low-mass galaxies that are more star forming may have undergone gas accretion processes that have rejuvenated their bulges into one last burst of more recent or even current star formation. These low-mass lenticulars may be undergoing or have undergone a compaction scenario.

Further work on spatially resolved populations of lenticulars and separating components using bulge/disc decomposition on even larger samples (including denser cluster environments) will reveal whether the two-mechanism formation scenario correlates with stellar mass alone, and what we may infer about lenticular formation mechanisms.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

datatable.fits

datatable2.fits

Please note: Oxford University Press is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Eric Emsellem and Cheng Li for useful discussions on the subject, and the anonymous referee for useful comments that improved this paper. AFM acknowledges support from STFC. MAF is grateful for financial support from the CONICYT Astronomy Program CAS-CONICYT project No. CAS17002, sponsored by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), through a grant to the CAS South America Center for Astronomy (CASSACA) in Santiago, Chile. Funding for the Sloan Digital Sky Survey IV has been provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, and the Participating Institutions. SDSS-IV acknowledges support and resources from the Center for High-Performance Computing at the University of Utah. The SDSS web site is www.sdss.org.

SDSS-IV is managed by the Astrophysical Research Consortium for the Participating Institutions of the SDSS Collaboration including the Brazilian Participation Group, the Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Mellon University, the Chilean Participation Group, the French Participation Group, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, The Johns Hopkins University, Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (IPMU)/University of Tokyo, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Leibniz Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam (AIP), Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie (MPIA Heidelberg), Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik (MPA Garching), Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik (MPE), National Astronomical Observatories of China, New Mexico State University, New York University, University of Notre Dame, Observatário Nacional/MCTI, The Ohio State University, Pennsylvania State University, Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, United Kingdom Participation Group, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, University of Arizona, University of Colorado Boulder, University of Oxford, University of Portsmouth, University of Utah, University of Virginia, University of Washington, University of Wisconsin, Vanderbilt University, and Yale University.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

APPENDIX A: DATA TABLES

Physical properties and derived quantities of the lenticular galaxies used in this work. Galaxy positional coordinates, photometric-derived structural parameters, derived stellar population measurements, and environmental indicators are included in this table. We present the first 10 lines as an illustrative example, and the rest will be available as an online table.

| MaNGA . | Right . | Declination . | Redshift . | Stellar mass . | b/a . | B/T . | Rb . | nb . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Qlss . | ηk . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | Ascension (deg) . | (deg) . | . | (|$\times 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|) . | . | . | . | . | log (age) . | log (age) . | [Z/H] . | [Z/H] . | . | . |

| (1) | (1) | (2) | (2) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (4) | ||||||

| 8078-3702 | 02:48:22 | +00:59:11.3 | 0.0274 | 0.195 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 0.52 | 0.242 | 0.558 | −0.175 | −0.34 | −2.325 | −0.371 |

| 8077-9102 | 02:48:34 | −00:32:59.5 | 0.0245 | 0.161 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1.6 | 1.18 | 0.018 | −0.016 | – | – | −1.598 | 0.252 |

| 8077-3704 | 02:48:48 | −00:06:33.1 | 0.0247 | 1.2 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 1.25 | 2.99 | 0.333 | 0.317 | −0.206 | −0.25 | −4.698 | −0.275 |

| 8081-1901 | 03:11:40 | +00:46:54.2 | 0.027 | 0.334 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 2.03 | 1.63 | 0.234 | 0.184 | −0.904 | −0.418 | Isolated | Isolated |

| 8081-12701 | 03:12:47 | −01:01:22.3 | 0.0815 | 18.1 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 2.87 | 2.39 | 0.482 | 0.422 | 0.144 | 0.22 | −0.728 | 0.131 |

| 8081-3701 | 03:14:18 | −00:36:34.9 | 0.1153 | 21.2 | 0.61 | 0.9 | 10.3 | 6.01 | 0.525 | −1.1 | 0.22 | 0.22 | −1.512 | 0.395 |

| 8082-3702 | 03:16:26 | +00:19:17.9 | 0.0214 | 0.0888 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.7 | 1.76 | 0.53 | 0.345 | −0.752 | −0.776 | −3.875 | −0.308 |

| 8082-6101 | 03:20:35 | −01:05:45.2 | 0.0214 | 0.0799 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.201 | 0.195 | −0.859 | −0.635 | −0.475 | 2.758 |

| 8082-1902 | 03:20:39 | −01:02:06.1 | 0.021 | 0.698 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 5.06 | 0.462 | 0.416 | −0.178 | −0.224 | −1.307 | 2.451 |

| 8084-9101 | 03:22:51 | +00:08:22.8 | 0.0228 | 0.173 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 2.29 | 1.92 | −0.005 | 0.16 | – | −0.39 | 0.148 | 1.066 |

| MaNGA . | Right . | Declination . | Redshift . | Stellar mass . | b/a . | B/T . | Rb . | nb . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Qlss . | ηk . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | Ascension (deg) . | (deg) . | . | (|$\times 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|) . | . | . | . | . | log (age) . | log (age) . | [Z/H] . | [Z/H] . | . | . |

| (1) | (1) | (2) | (2) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (4) | ||||||

| 8078-3702 | 02:48:22 | +00:59:11.3 | 0.0274 | 0.195 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 0.52 | 0.242 | 0.558 | −0.175 | −0.34 | −2.325 | −0.371 |

| 8077-9102 | 02:48:34 | −00:32:59.5 | 0.0245 | 0.161 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1.6 | 1.18 | 0.018 | −0.016 | – | – | −1.598 | 0.252 |

| 8077-3704 | 02:48:48 | −00:06:33.1 | 0.0247 | 1.2 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 1.25 | 2.99 | 0.333 | 0.317 | −0.206 | −0.25 | −4.698 | −0.275 |

| 8081-1901 | 03:11:40 | +00:46:54.2 | 0.027 | 0.334 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 2.03 | 1.63 | 0.234 | 0.184 | −0.904 | −0.418 | Isolated | Isolated |

| 8081-12701 | 03:12:47 | −01:01:22.3 | 0.0815 | 18.1 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 2.87 | 2.39 | 0.482 | 0.422 | 0.144 | 0.22 | −0.728 | 0.131 |

| 8081-3701 | 03:14:18 | −00:36:34.9 | 0.1153 | 21.2 | 0.61 | 0.9 | 10.3 | 6.01 | 0.525 | −1.1 | 0.22 | 0.22 | −1.512 | 0.395 |

| 8082-3702 | 03:16:26 | +00:19:17.9 | 0.0214 | 0.0888 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.7 | 1.76 | 0.53 | 0.345 | −0.752 | −0.776 | −3.875 | −0.308 |

| 8082-6101 | 03:20:35 | −01:05:45.2 | 0.0214 | 0.0799 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.201 | 0.195 | −0.859 | −0.635 | −0.475 | 2.758 |

| 8082-1902 | 03:20:39 | −01:02:06.1 | 0.021 | 0.698 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 5.06 | 0.462 | 0.416 | −0.178 | −0.224 | −1.307 | 2.451 |

| 8084-9101 | 03:22:51 | +00:08:22.8 | 0.0228 | 0.173 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 2.29 | 1.92 | −0.005 | 0.16 | – | −0.39 | 0.148 | 1.066 |

Physical properties and derived quantities of the lenticular galaxies used in this work. Galaxy positional coordinates, photometric-derived structural parameters, derived stellar population measurements, and environmental indicators are included in this table. We present the first 10 lines as an illustrative example, and the rest will be available as an online table.

| MaNGA . | Right . | Declination . | Redshift . | Stellar mass . | b/a . | B/T . | Rb . | nb . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Qlss . | ηk . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | Ascension (deg) . | (deg) . | . | (|$\times 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|) . | . | . | . | . | log (age) . | log (age) . | [Z/H] . | [Z/H] . | . | . |

| (1) | (1) | (2) | (2) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (4) | ||||||

| 8078-3702 | 02:48:22 | +00:59:11.3 | 0.0274 | 0.195 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 0.52 | 0.242 | 0.558 | −0.175 | −0.34 | −2.325 | −0.371 |

| 8077-9102 | 02:48:34 | −00:32:59.5 | 0.0245 | 0.161 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1.6 | 1.18 | 0.018 | −0.016 | – | – | −1.598 | 0.252 |

| 8077-3704 | 02:48:48 | −00:06:33.1 | 0.0247 | 1.2 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 1.25 | 2.99 | 0.333 | 0.317 | −0.206 | −0.25 | −4.698 | −0.275 |

| 8081-1901 | 03:11:40 | +00:46:54.2 | 0.027 | 0.334 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 2.03 | 1.63 | 0.234 | 0.184 | −0.904 | −0.418 | Isolated | Isolated |

| 8081-12701 | 03:12:47 | −01:01:22.3 | 0.0815 | 18.1 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 2.87 | 2.39 | 0.482 | 0.422 | 0.144 | 0.22 | −0.728 | 0.131 |

| 8081-3701 | 03:14:18 | −00:36:34.9 | 0.1153 | 21.2 | 0.61 | 0.9 | 10.3 | 6.01 | 0.525 | −1.1 | 0.22 | 0.22 | −1.512 | 0.395 |

| 8082-3702 | 03:16:26 | +00:19:17.9 | 0.0214 | 0.0888 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.7 | 1.76 | 0.53 | 0.345 | −0.752 | −0.776 | −3.875 | −0.308 |

| 8082-6101 | 03:20:35 | −01:05:45.2 | 0.0214 | 0.0799 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.201 | 0.195 | −0.859 | −0.635 | −0.475 | 2.758 |

| 8082-1902 | 03:20:39 | −01:02:06.1 | 0.021 | 0.698 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 5.06 | 0.462 | 0.416 | −0.178 | −0.224 | −1.307 | 2.451 |

| 8084-9101 | 03:22:51 | +00:08:22.8 | 0.0228 | 0.173 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 2.29 | 1.92 | −0.005 | 0.16 | – | −0.39 | 0.148 | 1.066 |

| MaNGA . | Right . | Declination . | Redshift . | Stellar mass . | b/a . | B/T . | Rb . | nb . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Qlss . | ηk . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | Ascension (deg) . | (deg) . | . | (|$\times 10^{10}\, \textrm{M}_{\odot }$|) . | . | . | . | . | log (age) . | log (age) . | [Z/H] . | [Z/H] . | . | . |

| (1) | (1) | (2) | (2) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (4) | ||||||

| 8078-3702 | 02:48:22 | +00:59:11.3 | 0.0274 | 0.195 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 0.52 | 0.242 | 0.558 | −0.175 | −0.34 | −2.325 | −0.371 |

| 8077-9102 | 02:48:34 | −00:32:59.5 | 0.0245 | 0.161 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1.6 | 1.18 | 0.018 | −0.016 | – | – | −1.598 | 0.252 |

| 8077-3704 | 02:48:48 | −00:06:33.1 | 0.0247 | 1.2 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 1.25 | 2.99 | 0.333 | 0.317 | −0.206 | −0.25 | −4.698 | −0.275 |

| 8081-1901 | 03:11:40 | +00:46:54.2 | 0.027 | 0.334 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 2.03 | 1.63 | 0.234 | 0.184 | −0.904 | −0.418 | Isolated | Isolated |

| 8081-12701 | 03:12:47 | −01:01:22.3 | 0.0815 | 18.1 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 2.87 | 2.39 | 0.482 | 0.422 | 0.144 | 0.22 | −0.728 | 0.131 |

| 8081-3701 | 03:14:18 | −00:36:34.9 | 0.1153 | 21.2 | 0.61 | 0.9 | 10.3 | 6.01 | 0.525 | −1.1 | 0.22 | 0.22 | −1.512 | 0.395 |

| 8082-3702 | 03:16:26 | +00:19:17.9 | 0.0214 | 0.0888 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.7 | 1.76 | 0.53 | 0.345 | −0.752 | −0.776 | −3.875 | −0.308 |

| 8082-6101 | 03:20:35 | −01:05:45.2 | 0.0214 | 0.0799 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 1.11 | 0.201 | 0.195 | −0.859 | −0.635 | −0.475 | 2.758 |

| 8082-1902 | 03:20:39 | −01:02:06.1 | 0.021 | 0.698 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 5.06 | 0.462 | 0.416 | −0.178 | −0.224 | −1.307 | 2.451 |

| 8084-9101 | 03:22:51 | +00:08:22.8 | 0.0228 | 0.173 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 2.29 | 1.92 | −0.005 | 0.16 | – | −0.39 | 0.148 | 1.066 |

Measured spectral indices for lenticular galaxies in this work. Here, we present the averaged bulge and disc index measurements in Ångström, for each galaxy in the S0 sample. We present the first 10 lines as an illustrative example, and the rest will be available as an online table.

| MaNGA . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | H β . | H β . | Mgb . | Mgb . | Fe5270 . | Fe5270 . | Fe5335 . | Fe5335 . |

| 8078-3702 | 3.161 | 2.315 | 2.288 | 2.53 | 3.065 | 3.08 | 2.163 | 2.231 |

| 8077-9102 | 4.092 | 4.315 | 1.43 | 1.616 | 1.319 | 1.925 | 1.563 | 2.004 |

| 8077-3704 | 2.877 | 2.929 | 2.724 | 2.745 | 2.806 | 2.509 | 2.649 | 2.709 |

| 8081-1901 | 3.765 | 3.793 | 1.696 | 1.992 | 1.147 | 1.854 | 1.326 | 1.836 |

| 8081-12701 | 2.42 | 2.565 | 4.953 | 8.053 | 2.73 | 3.081 | 2.728 | 2.656 |

| 8081-3701 | 2.314 | – | 4.469 | – | 3.839 | – | 2.759 | – |

| 8082-3702 | 2.757 | 3.27 | 1.684 | 1.741 | 2.066 | 2.025 | 2.197 | 1.581 |

| 8082-6101 | 3.914 | 3.734 | 1.027 | 1.516 | 2.582 | 2.15 | 1.0 | 1.588 |

| 8082-1902 | 2.527 | 2.632 | 2.849 | 2.844 | 2.828 | 2.688 | 2.562 | 2.289 |

| 8084-9101 | 4.243 | 3.513 | 1.592 | 1.643 | 2.373 | 2.353 | 1.534 | 2.174 |

| MaNGA . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | H β . | H β . | Mgb . | Mgb . | Fe5270 . | Fe5270 . | Fe5335 . | Fe5335 . |

| 8078-3702 | 3.161 | 2.315 | 2.288 | 2.53 | 3.065 | 3.08 | 2.163 | 2.231 |

| 8077-9102 | 4.092 | 4.315 | 1.43 | 1.616 | 1.319 | 1.925 | 1.563 | 2.004 |

| 8077-3704 | 2.877 | 2.929 | 2.724 | 2.745 | 2.806 | 2.509 | 2.649 | 2.709 |

| 8081-1901 | 3.765 | 3.793 | 1.696 | 1.992 | 1.147 | 1.854 | 1.326 | 1.836 |

| 8081-12701 | 2.42 | 2.565 | 4.953 | 8.053 | 2.73 | 3.081 | 2.728 | 2.656 |

| 8081-3701 | 2.314 | – | 4.469 | – | 3.839 | – | 2.759 | – |

| 8082-3702 | 2.757 | 3.27 | 1.684 | 1.741 | 2.066 | 2.025 | 2.197 | 1.581 |

| 8082-6101 | 3.914 | 3.734 | 1.027 | 1.516 | 2.582 | 2.15 | 1.0 | 1.588 |

| 8082-1902 | 2.527 | 2.632 | 2.849 | 2.844 | 2.828 | 2.688 | 2.562 | 2.289 |

| 8084-9101 | 4.243 | 3.513 | 1.592 | 1.643 | 2.373 | 2.353 | 1.534 | 2.174 |

Measured spectral indices for lenticular galaxies in this work. Here, we present the averaged bulge and disc index measurements in Ångström, for each galaxy in the S0 sample. We present the first 10 lines as an illustrative example, and the rest will be available as an online table.

| MaNGA . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | H β . | H β . | Mgb . | Mgb . | Fe5270 . | Fe5270 . | Fe5335 . | Fe5335 . |

| 8078-3702 | 3.161 | 2.315 | 2.288 | 2.53 | 3.065 | 3.08 | 2.163 | 2.231 |

| 8077-9102 | 4.092 | 4.315 | 1.43 | 1.616 | 1.319 | 1.925 | 1.563 | 2.004 |

| 8077-3704 | 2.877 | 2.929 | 2.724 | 2.745 | 2.806 | 2.509 | 2.649 | 2.709 |

| 8081-1901 | 3.765 | 3.793 | 1.696 | 1.992 | 1.147 | 1.854 | 1.326 | 1.836 |

| 8081-12701 | 2.42 | 2.565 | 4.953 | 8.053 | 2.73 | 3.081 | 2.728 | 2.656 |

| 8081-3701 | 2.314 | – | 4.469 | – | 3.839 | – | 2.759 | – |

| 8082-3702 | 2.757 | 3.27 | 1.684 | 1.741 | 2.066 | 2.025 | 2.197 | 1.581 |

| 8082-6101 | 3.914 | 3.734 | 1.027 | 1.516 | 2.582 | 2.15 | 1.0 | 1.588 |

| 8082-1902 | 2.527 | 2.632 | 2.849 | 2.844 | 2.828 | 2.688 | 2.562 | 2.289 |

| 8084-9101 | 4.243 | 3.513 | 1.592 | 1.643 | 2.373 | 2.353 | 1.534 | 2.174 |

| MaNGA . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . | Bulge . | Disc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-IFU . | H β . | H β . | Mgb . | Mgb . | Fe5270 . | Fe5270 . | Fe5335 . | Fe5335 . |

| 8078-3702 | 3.161 | 2.315 | 2.288 | 2.53 | 3.065 | 3.08 | 2.163 | 2.231 |

| 8077-9102 | 4.092 | 4.315 | 1.43 | 1.616 | 1.319 | 1.925 | 1.563 | 2.004 |

| 8077-3704 | 2.877 | 2.929 | 2.724 | 2.745 | 2.806 | 2.509 | 2.649 | 2.709 |

| 8081-1901 | 3.765 | 3.793 | 1.696 | 1.992 | 1.147 | 1.854 | 1.326 | 1.836 |

| 8081-12701 | 2.42 | 2.565 | 4.953 | 8.053 | 2.73 | 3.081 | 2.728 | 2.656 |

| 8081-3701 | 2.314 | – | 4.469 | – | 3.839 | – | 2.759 | – |

| 8082-3702 | 2.757 | 3.27 | 1.684 | 1.741 | 2.066 | 2.025 | 2.197 | 1.581 |

| 8082-6101 | 3.914 | 3.734 | 1.027 | 1.516 | 2.582 | 2.15 | 1.0 | 1.588 |

| 8082-1902 | 2.527 | 2.632 | 2.849 | 2.844 | 2.828 | 2.688 | 2.562 | 2.289 |

| 8084-9101 | 4.243 | 3.513 | 1.592 | 1.643 | 2.373 | 2.353 | 1.534 | 2.174 |