-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Begoña Monge-Maillo, Francesca F Norman, Sandra Chamorro-Tojeiro, Francesca Gioia, José-Antonio Pérez-Molina, Carmen Chicharro, Javier Moreno, Rogelio López-Vélez, Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum in an HIV-negative patient treated with miltefosine, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 29, Issue 7, October 2022, taab169, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taab169

Close - Share Icon Share

A 65-year-old Nigerian man presented in May 2018 with a cutaneous lesion on the left ear that developed in January 2018. He migrated to Spain in 1995 and had not travelled since. He had dyslipidaemia, Type-II diabetes and was HIV-negative. In 2013, he was treated for visceral leishmaniasis (VL) due to Leishmania infantum with liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB; 18-mg/kg total dose).

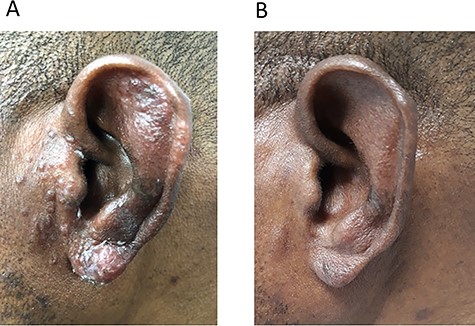

On examination the cutaneous lesion presented as an area of thickening and swelling mainly in the helix, scapha, triangular fossa and lobule with nodular lesions on the tragus (Figure 1A). No evidence of other alterations in the rest of the physical examination. Several possible diagnoses were considered such as cutaneous malignant lesions (e.g. cutaneous T cell lymphoma), xanthoma or primary cutaneous leishmaniasis. A biopsy of the cutaneous lesion was performed and informed as inflammatory and granulomatous reaction with morphological traces that suggest leishmansis without being able to observe parasites. Diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis was confirmed with a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for leishmania parasite DNA. Blood tests showed only mild hyperglycaemia and HIV serology was negative. Leishmania serology was positive (immunofluorescence, IFAT titres 1/160). Peripheral PCR was performed on complete peripheral blood using the gene SSuRNA (small subunit ribosomal ribonucleic) as the target for parasite detecting DNA with a negative result. Abdominal ultrasonography ruled out hepatosplenomegaly. The previous history of VL made it necessary to evaluate if this cutaneous lesion could be related. Therefore, a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP), with Hae III, Rsa I enzymes, was performed on samples from the cutaneous biopsy and from the bone marrow biopsy obtained in 2013. Identical electrophoretic profiles were obtained, demonstrating infection due to the same Leishmania strain. A diagnosis of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) due to L. infantum 5 years after the initial VL episode was established.

Treatment was initiated in July 2018 with L-AmB (40 mg/Kg total dose) but the patient developed a severe infusion reaction with chest, flank and abdominal pain and dyspnoea in the first few minutes of infusion. New infusion with premedication and slower infusion was proposed but the patient refused the treatment. Oral miltefosine (150 mg/day for 28 days) was administered in August 2018 with a favourable initial response at Day 21 and complete healing at Day 28 of treatment. However, in March 2019 the patient referred new cutaneous lesions of the same ear. On examination, the infiltration and inflammation of the helix and scapha had improved and nearly disappeared but new signs of inflammation were present in the auricular lobe. New biopsy specimen was PCR positive for Leishmania sp. Three therapeutic options were suggested and discussed with the patient: (i) L-AmB 40 mg/Kg total dose and (ii) Miltefosine 150 mg/day for 3 months; Combination therapy of L-AmB plus miltefosine. Finally, relapse of PKDL was treated with a 3-month course of miltefosine (150 mg/day) from March until June 2019. Follow up of the patient was performed with hematologic and biochemistry periodic test and anamnesis searching for secondary effects and adherence. Good treatment compliance and good tolerance were reported developing only mild gastrointestinal side effects (isolated episode of diarrhoea treated with domperidone). Resolution of the lesion was observed 10 days before completing the three moths’ treatment regimen. The patient was last evaluated in April 2021 and lesions remained cured (Figure 1B).

PKDL occurs as a complication of VL, mainly due to Leishmania donovani in the Indian Subcontinent (IS) and East Africa (EA). PKDL caused by L. infantum is rare and mostly described in patients immunocompromised due to HIV. Studies on the pathogenesis of PKDL have demonstrated that L. donovani may change from exhibiting viscerotropic to dermatotropic properties probably induced by immunoregulatory mechanisms of the host immune system.1 The causes for the development of dermotropism in L. donovani infections are largely unknown and L. infantum appears to exceptionally develop dermotropism following VL episodes in cases where a degree of immunosuppression occurs (for this patient diabetes mellitus could have contributed to immunosuppression).

This PKDL case occurs 7 years after the VL episode as it has been described in the literature where PKDL is reported within months to several years (usually 2–7 years) after apparent cure of VL. In many cases diagnosis of PKDL is based on clinical and epidemiological parameters but isolation of the parasite by microscopic examination of the slit smears or skin biopsy is considered the gold standard. However, the reported sensitivity of microscopy is, at best, 40–60% with nodular lesions or even lower in patients with macular lesions.2 In this case microscopy was suggestive of CL but parasites were finally identified by PCR. PCR has already been shown as the diagnosis test with the highest sensitivity compared with other diagnosis techniques and can identify the Leishmania specie involved.2 Electrophoretic profile obtained after the amplification of the kinetoplast DNA and its subsequent digestion with different restriction enzymes (PCR-RFLP) was performed because it is characteristic for each of the Leishmania strains and remains stable over time. This allows a space–time tracking and to distinguish reinfections from relapses.3 Serological tests are usually positive but are of limited value because a positive result may be caused by antibodies persisting after a past VL. It can be helpful when other diseases are considered in the differential diagnosis, or if previous VL is uncertain.4 In this case, it was interpreted as a confirmation of the previous VL, but results were not used as the final diagnosis test due to its low specificity in PKDL cases.

Due to scarce experience with L. infantum-PKDL, therapeutic options considered were based on treatment of L. donovani in the IS and EA.4 In this case, an initial 1-month treatment regimen with miltefosine failed to achieve cure. Published data have suggested improved results with 12 weeks of miltefosine for PKDL, with major inconveniences being potential gastrointestinal side effects and development of drug resistance.5 However, no resistance to miltefosine has currently been described for L. infantum and in this case the patient presented good tolerance to the drug and a favourable outcome.

This case highlights that PKDL due to L. infantum must be taken into account in the differential diagnosis on cutaneous lesions in endemic areas also in patients with other types of immunosuppression different from HIV. Furthermore, this case shows an effective therapeutic option, which may be of great help for other physicians given the scarce knowledge about it. The correct diagnosis and management of these cases may impact not only on the patients’ health but also on a public health point of view due its potential effect as important reservoirs for Leishmania.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the clinical management of the patient and interpretation of the data. BMM wrote the paper, the co-authors reviewed the final draft.

Funding

Support was provided by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III project ‘RD16/0027/0020’ Red de Enfermedades Tropicales, Subprograma RETICS del Plan Estatal de I + D + I.

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to declare.