-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Matteo Piccica, Filippo Lagi, Alessandro Bartoloni, Lorenzo Zammarchi, Efficacy and safety of pentamidine isethionate for tegumentary and visceral human leishmaniasis: a systematic review, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 6, August 2021, taab065, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taab065

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We performed a systematic review of the literature to investigate the efficacy and safety of pentamidine isethionate for the treatment of human tegumentary and visceral leishmaniasis.

A total of 616 papers were evaluated, and 88 studies reporting data on 3108 cases of leishmaniasis (2082 patients with tegumentary leishmaniasis and 1026 with visceral leishmaniasis) were finally included. The majority of available studies were on New World cutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania donovani. At the same time, few data are available for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, mucosal leishmaniasis, and visceral leishmaniasis caused by L. infantum. Pooled cure rate for tegumentary leishmaniasis was 78.8% (CI 95%, 76.9–80.6%) and 92.7% (CI 95%, 88.3–97.1%) according to controlled randomized trial and observational studies and case report and case series respectively. Pooled cure rate for visceral leishmaniasis was 84.8% (CI 95%, 82.6–87.1%) and 90.7% (CI 95%, 84.1–97.3%) according to controlled randomized trial and observational studies and case report and case series, respectively. Comparable cure rate was observed in recurrent and refractory cases of visceral leishmaniasis. Concerning the safety profile, among about 2000 treated subjects with some available information, the most relevant side effects were six cases of arrhythmia (including four cases of fatal ventricular fibrillation), 20 cases of irreversible diabetes, 26 cases of muscular aseptic abscess following intramuscular administration.

Pentamidine isethionate is associated with a similar cure rate of the first-line anti-leishmanial drugs. Severe and irreversible adverse effect appear to be rare. The drug may still have a role in the treatment of any form of human leishmaniasis when the first-line option has failed or in patients who cannot tolerate other drugs also in the setting of travel medicine. In difficult cases, the drug can also be considered as a component of a combination treatment regimen.

Introduction

Leishmaniasis remains an important global problem. It is still one of the world’s most neglected diseases, affecting predominantly individuals of the lowest socioeconomic status, mainly in developing countries: 350 million people are considered at risk of contracting leishmaniasis, and ~2 million new cases occur yearly.1 It is estimated to cause the ninth largest disease burden among individual infectious diseases.2 At least 20 species of the genus Leishmania are pathogenic for humans. Clinical manifestations in humans range from latent infections and localized skin and mucous ulcers to fatal systemic disease. The main clinical syndromes are visceral and tegumentary leishmaniasis (TL), including the cutaneous, mucocutaneous and mucosal form.2

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the most common form of the disease caused by various species endemic in both the New and the Old World.1 CL is responsible for chronic cutaneous lesions, which may cause disfiguration and stigma in affected individuals. Mucosal leishmaniasis (ML) may be the first and only documentable pathological condition due to leishmania or can be either accompanied or preceded by cutaneous or visceral leishmaniasis. It may be caused by any leishmania species even thus is fairly more common in South America. In the New World mucosal involvement is commonly seen as a consequence of a cutaneous infection caused by L. braziliensis (or related species), which spread to the mucosae (muco-cutaneous leishmaniasis, MCL) causing disruptive involvement of the upper airways and possibly fatal complications.3

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a systemic disease that is fatal if left untreated and is caused by the Leishmania donovani complex, which includes two species: L. donovani sensu stricto (endemic in East Africa and the Indian subcontinent) and L. infantum, which is endemic especially in the Mediterranean basin and Latin America.4

Both TL and VL may affect immunosuppressed as well as immunocompetent individuals. However advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or treatment with immunosuppressive drugs represent recognized risk factors for the development of clinical disease as well as treatment failure and relapse.5

Leishmaniasis is also a relevant disease in the setting of travel and migration medicine. Classically TL can be observed in international adventurous tourists visiting naturalistic destinations in Latin America, military personals returning from missions in the Middle East and in refugees form endemic areas. Travel related cases of VL are also reported for example in tourists visiting the Mediterranean basin.6–8

Management of leishmaniasis is complicated and depends upon several factors such as the clinical syndrome, disease severity, the causative organism, individual characteristics of the patient, the local availability of drugs and the experience of clinicians in the use of a specific drug. According to the clinical guidelines9 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH), the large majority of available evidence (76%) guiding recommendations are of low or very low quality, primarily for the absence of well conducted randomized clinical trials. For these reasons, the treatment of leishmaniasis is poorly standardized.

Concerning TL there is no treatment of choice, and it should be individualized. Treatment options include a wide range of interventions ranging from local physical treatment (heat and cryo-therapy) to local or parenteral drugs. Systemic drug options include a limited number of molecules. Most of those options need parenteral administration and are burdened by a high frequency of side effects. Systemic drug options include pentavalent antimonial (as sodium stibogluconate or meglumine antimoniate), amphotericin B deoxycholate, lipid formulations of amphotericin B, paromomycin, and pentamidine isethionate (PI) administered intramuscularly or intravenously. Miltefosine and azoles are also available as orally administered drug. Local administration of drugs includes topical paramomycin/methylbenzethonium chloride cream, intralesional antimonials and intralesional PI.

An additional challenge is represented by refractory or recurrent leishmaniasis, which is observed most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals. The guidelines do not provide a standardized approach for these cases, but repeated treatment course with different drugs or combination treatment are frequently used.10,11 Maintenance therapy (or so-called secondary prophylaxis) is recommended after a full course of treatment to prevent relapses in severely immunocompromised HIV/VL coinfected patients until adequate immune reconstitution is obtained.12,13

PI is commonly considered a ‘lesser alternative’ treatment option by the majority of guidelines because of possible irreversible toxicity and lower efficacy compared to other drugs. Table 1 summarizes the indication for the use of PI by some recent guidelines. This systematic review aims to summarize the available evidence on the efficacy and safety of PI, to verify whether the drug has still a role in the management of leishmaniasis.

Recommendations on the use of pentamidine isethionate according to main recent guidelines on clinical management of leishmaniasis

| Guidelines . | Indication . | Treatment schedule . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDSA-ASTMH guidelines 20169 | CL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 3–4 mg/kg every other day for three or four doses | No FDA approved for CL, off-label use. L. (V.) panamensis/guyanensis: an alternative regimen is 2 mg/kg every other day for seven doses |

| ML treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 2–4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ≥15 doses | No FDA approved for ML, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’ | |

| VL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ∼15–30 doses | No FDA approved for VL, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’. Considered second-line therapy because of toxicity and lower efficacy | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | Not reported | Is an option | |

| Manual on case management and surveillance of the leishmaniasis in the WHO European Region 2017106 | Treatment of diffuse CL by L. aethiopica | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Third option listed |

| Treatment of CL by L. guyanensis and L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Second option listed | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IM 4 mg/kg/day every 2–4 weeks | Fourth option listed | |

| Leishmaniases in the Americas Treatment Recommendations 2018128 | CL treatment | IM 3–4 mg/kg/day for three to four doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations. Better results with L. guyanensis. Considered first-line option for L. guyanensis and L. panamensis |

| ML treatment | IM 3 to 4 mg/kg/day for 7–10 doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations | |

| Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis | Not reported | Third option listed | |

| Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV129 | Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IV 6 mg/kg every 2–4 weeks | Suggested as alternative for secondary prophylaxis (not formally recommended) |

| LeishMan recommendations for treatment of cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis in travellers, 2014126 | Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | |

| Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. guyanensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days |

| Guidelines . | Indication . | Treatment schedule . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDSA-ASTMH guidelines 20169 | CL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 3–4 mg/kg every other day for three or four doses | No FDA approved for CL, off-label use. L. (V.) panamensis/guyanensis: an alternative regimen is 2 mg/kg every other day for seven doses |

| ML treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 2–4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ≥15 doses | No FDA approved for ML, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’ | |

| VL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ∼15–30 doses | No FDA approved for VL, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’. Considered second-line therapy because of toxicity and lower efficacy | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | Not reported | Is an option | |

| Manual on case management and surveillance of the leishmaniasis in the WHO European Region 2017106 | Treatment of diffuse CL by L. aethiopica | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Third option listed |

| Treatment of CL by L. guyanensis and L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Second option listed | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IM 4 mg/kg/day every 2–4 weeks | Fourth option listed | |

| Leishmaniases in the Americas Treatment Recommendations 2018128 | CL treatment | IM 3–4 mg/kg/day for three to four doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations. Better results with L. guyanensis. Considered first-line option for L. guyanensis and L. panamensis |

| ML treatment | IM 3 to 4 mg/kg/day for 7–10 doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations | |

| Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis | Not reported | Third option listed | |

| Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV129 | Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IV 6 mg/kg every 2–4 weeks | Suggested as alternative for secondary prophylaxis (not formally recommended) |

| LeishMan recommendations for treatment of cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis in travellers, 2014126 | Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | |

| Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. guyanensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days |

IDSA=Infectious Diseases Society of America; ASTMH = American Society of Tropical; IM = intramuscular; IV: intravenous; CL=cutaneous leishmaniasis; ML=mucosal leishmaniasis

Recommendations on the use of pentamidine isethionate according to main recent guidelines on clinical management of leishmaniasis

| Guidelines . | Indication . | Treatment schedule . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDSA-ASTMH guidelines 20169 | CL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 3–4 mg/kg every other day for three or four doses | No FDA approved for CL, off-label use. L. (V.) panamensis/guyanensis: an alternative regimen is 2 mg/kg every other day for seven doses |

| ML treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 2–4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ≥15 doses | No FDA approved for ML, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’ | |

| VL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ∼15–30 doses | No FDA approved for VL, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’. Considered second-line therapy because of toxicity and lower efficacy | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | Not reported | Is an option | |

| Manual on case management and surveillance of the leishmaniasis in the WHO European Region 2017106 | Treatment of diffuse CL by L. aethiopica | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Third option listed |

| Treatment of CL by L. guyanensis and L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Second option listed | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IM 4 mg/kg/day every 2–4 weeks | Fourth option listed | |

| Leishmaniases in the Americas Treatment Recommendations 2018128 | CL treatment | IM 3–4 mg/kg/day for three to four doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations. Better results with L. guyanensis. Considered first-line option for L. guyanensis and L. panamensis |

| ML treatment | IM 3 to 4 mg/kg/day for 7–10 doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations | |

| Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis | Not reported | Third option listed | |

| Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV129 | Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IV 6 mg/kg every 2–4 weeks | Suggested as alternative for secondary prophylaxis (not formally recommended) |

| LeishMan recommendations for treatment of cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis in travellers, 2014126 | Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | |

| Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. guyanensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days |

| Guidelines . | Indication . | Treatment schedule . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDSA-ASTMH guidelines 20169 | CL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 3–4 mg/kg every other day for three or four doses | No FDA approved for CL, off-label use. L. (V.) panamensis/guyanensis: an alternative regimen is 2 mg/kg every other day for seven doses |

| ML treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 2–4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ≥15 doses | No FDA approved for ML, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’ | |

| VL treatment | IM or IV (IV preferred in North America) 4 mg/kg every other day or three times per week for ∼15–30 doses | No FDA approved for VL, off-label use. Classified as ‘lesser alternative’. Considered second-line therapy because of toxicity and lower efficacy | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | Not reported | Is an option | |

| Manual on case management and surveillance of the leishmaniasis in the WHO European Region 2017106 | Treatment of diffuse CL by L. aethiopica | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Third option listed |

| Treatment of CL by L. guyanensis and L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | Second option listed | |

| Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IM 4 mg/kg/day every 2–4 weeks | Fourth option listed | |

| Leishmaniases in the Americas Treatment Recommendations 2018128 | CL treatment | IM 3–4 mg/kg/day for three to four doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations. Better results with L. guyanensis. Considered first-line option for L. guyanensis and L. panamensis |

| ML treatment | IM 3 to 4 mg/kg/day for 7–10 doses on alternate days | In cases of therapeutic failure with first-line option or in special situations | |

| Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis | Not reported | Third option listed | |

| Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV129 | Secondary prophylaxis for VL in HIV patients | IV 6 mg/kg every 2–4 weeks | Suggested as alternative for secondary prophylaxis (not formally recommended) |

| LeishMan recommendations for treatment of cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis in travellers, 2014126 | Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. panamensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days | |

| Treatment of complicated cutaneous by L. guyanensis | IV 4 mg/kg, three infusions over 5 days |

IDSA=Infectious Diseases Society of America; ASTMH = American Society of Tropical; IM = intramuscular; IV: intravenous; CL=cutaneous leishmaniasis; ML=mucosal leishmaniasis

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to assess the efficacy of PI for TL and VL following the PICO question.

Population: subjects with TL (which include CL, ML and MCL) and VL.

Intervention: use of PI.

Comparison: antimonials, amphotericin B, paromomycin, azoles, miltefosine, placebo, or no treatment for TL and VL.

Outcome: cure rate.

Secondary objectives were to assess adverse drug reactions, compare various administration routes (intramuscular, intravenous), evaluate different response between different geographical settings and determine rates of relapse of the diseases after treatment.

Method

The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42020142906, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=142906). Recommendation of the PRISMA statement was followed.14

Eligibility criteria

We included clinical trials (randomized clinical trials (RCTs), including cluster RCTs and controlled non-randomized clinical trials (CCTs), including dose-ranging studies) on the treatment of any clinical form of human leishmaniasis with PI alone or in combination with another drug. Cases of leishmaniasis should have to be confirmed by microscopic examination, histopathology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis or culture. Prospective and Retrospective observational studies were also included. Considering the rare use of this drug, we decided to include also case series and case reports. We excluded systematic reviews and meta-analyses. However, the reference list of this type of study was screened to retrieve additional eligible papers. We included studies examining both the general adult human population and infants. We included articles reported in English, French, Spanish and Italian language. We excluded studies in animals or conducted in vitro.

The authors reviewed all studies matching the eligibility criteria, and disagreements on inclusion were resolved by consensus.

Outcome

We included original articles evaluating the cure rate of VL and TL with PI. Double-arm studies comparing PI with the control group (placebo or any other intervention) and single-arm studies in which the group has been treated with PI were included. Patients of all ages were considered.

Relapse was defined as a new appearance of the disease after the cure.

As an additional outcome, we reported the type, rate, and severity of adverse drug reactions (any immediate or delayed side effects of any degree of severity).

Comparators

We evaluated the effect of PI in comparison to any other anti-leishmania drug, namely antimonials (meglumine antimoniate or sodium stibogluconate), any formulation of amphotericin B, paromomycin, azoles, miltefosine, placebo or no treatment.

Timing

For CL and ML we evaluated the outcome at 30–90 days, 91–180 days, 181–365 days. For VL we assessed the outcome at 15–30 days, 31–45 days and 46–90 days.

Information sources and search strategy

Two reviewers independently and systematically searched PubMed and Cochrane databases. The search strategy included key terms related to the intervention and the disease adapted to both databases. A manual search of the references of the affine review was also conducted. Furthermore, to identify useful grey literature, moreover google scholar was also screened. The detailed search strategy is described in supplementary material 1. A preliminary screening of the searched items was made by reading titles and abstracts of each article. Therefore, the selected full texts were read thoroughly to assess their eligibility and to extract data.

Data extraction

Data from each article were extracted using an electronic Excel database where we recorded first author name, year of publication, type of study, number of patients, the eventual presence of a comparator drug, way of administration and dose of PI, clinical form of leishmaniasis, Leishmania species. As for outcome descriptions we used standardized definitions, and we also reported the duration of follow-up.

Study quality assessment

Since we decided to include any type of study, including single case reports to retrieve information on possible rare side effects of the drugs, we chose not to perform a formal quality assessment of the studies.

Results

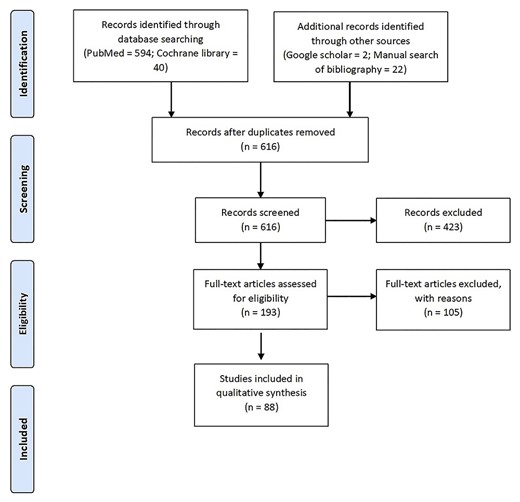

The selection process of articles is reported in figure 1. Among the 616 papers identified, 88 studies were finally included involving 3108 patients affected by any form of leishmaniasis and treated with PI.

Of these studies, 34 papers were about VL for a total of 1026 patients (950 from studies and 76 from case report/case series).

The remaining 54 studies were about TL (53 on CL and one on ML) involving 2082 patients (1945 from studies and 137 from case report/case series).

Among the 54 papers about TL, nine were retrospective studies,15–23 16 were prospective non-randomized,24–32,33–38 two were randomized clinical trials.39,40 Among the remaining 27 papers, 18 were case reports41–58 and nine were case series.59–67 Of these 54 studies 45 were conducted in the New World (26 retrospective/prospective studies and 19 case report/case series) and nine in the Old World (one retrospective/prospective studies and eight case report/case series).

Among the 34 included studies on VL, four were retrospective studies,68–71 four were prospective non randomized72–75and two were a randomized clinical trial.76,77 The remaining 24 were case reports (21)10,78–97 and case series (three).98–100

Tables 2 and 3 report the overall pooled cure rate and side effects frequency in patients with leishmaniasis treated with parenteral PI by type of studies and clinical form of leishmaniasis.

Pooled cure rate efficacy in patients with leishmaniasis treated with parenteral pentamidine by type of studies and clinical form of leishmaniasis

| Disease . | Study type . | Cured patients . | Treated patients . | Cure rate (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | RCT and observational | 1533 | 1945 | 78.8% (76.9–80.6) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (all studies) | RCT and observational | 806 | 950 | 84.8 (82.6–87.1) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (pentamidine used as second line) | RCT and observational | 673 | 750 | 89.7 (87.6–91.9) |

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 127 | 137 | 92.7 (88.3–97.1) |

| NWCL | Case report/case series | 110 | 115 | 95.7 (91.9–99.4) |

| OWCL | Case report/case series | 17 | 22 | 77.3 (59.8–94.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 68 | 75 | 90.7 (84.1–97.3) |

| Disease . | Study type . | Cured patients . | Treated patients . | Cure rate (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | RCT and observational | 1533 | 1945 | 78.8% (76.9–80.6) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (all studies) | RCT and observational | 806 | 950 | 84.8 (82.6–87.1) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (pentamidine used as second line) | RCT and observational | 673 | 750 | 89.7 (87.6–91.9) |

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 127 | 137 | 92.7 (88.3–97.1) |

| NWCL | Case report/case series | 110 | 115 | 95.7 (91.9–99.4) |

| OWCL | Case report/case series | 17 | 22 | 77.3 (59.8–94.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 68 | 75 | 90.7 (84.1–97.3) |

RCT: randomized controlled trials; NWCL: new world cutaneous leishmaniasis; OWCL: old world cutaneous leishmaniasis

Pooled cure rate efficacy in patients with leishmaniasis treated with parenteral pentamidine by type of studies and clinical form of leishmaniasis

| Disease . | Study type . | Cured patients . | Treated patients . | Cure rate (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | RCT and observational | 1533 | 1945 | 78.8% (76.9–80.6) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (all studies) | RCT and observational | 806 | 950 | 84.8 (82.6–87.1) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (pentamidine used as second line) | RCT and observational | 673 | 750 | 89.7 (87.6–91.9) |

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 127 | 137 | 92.7 (88.3–97.1) |

| NWCL | Case report/case series | 110 | 115 | 95.7 (91.9–99.4) |

| OWCL | Case report/case series | 17 | 22 | 77.3 (59.8–94.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 68 | 75 | 90.7 (84.1–97.3) |

| Disease . | Study type . | Cured patients . | Treated patients . | Cure rate (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | RCT and observational | 1533 | 1945 | 78.8% (76.9–80.6) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (all studies) | RCT and observational | 806 | 950 | 84.8 (82.6–87.1) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (pentamidine used as second line) | RCT and observational | 673 | 750 | 89.7 (87.6–91.9) |

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 127 | 137 | 92.7 (88.3–97.1) |

| NWCL | Case report/case series | 110 | 115 | 95.7 (91.9–99.4) |

| OWCL | Case report/case series | 17 | 22 | 77.3 (59.8–94.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | Case report/case series | 68 | 75 | 90.7 (84.1–97.3) |

RCT: randomized controlled trials; NWCL: new world cutaneous leishmaniasis; OWCL: old world cutaneous leishmaniasis

Pooled side effects frequency in patients with leishmaniasis treated with parenteral pentamidine by type of studies and clinical form of leishmaniasis

| Type of side effect . | Study type . | Number of events . | Treated patients . | Frequency (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | ||||

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 604 | 1439 | 42 (39.5–44.6) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 2 | 1439 | 0.14 (−0.05–0.33) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 29 | 1439 | 2 (1.28–2.72) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 17 | 1360# | 1.25 (0.66–1.84) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 6 | 79 | 7.6 (1.8–13.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 37 | 79 | 46.8 (35.8–57.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 905 | 1.5 (0.7–2.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 905 | 3.0 (1.9–4.1) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 905 | 1.9 (1–2.8) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 193 | 905 | 21.3 (18.7–24) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 4* | 905 | 0.4 (0–0.9) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 56 | 905 | 6.2 (4.6–7.8) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 8 | 381# | 2.1 (0.7–3.5) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 4 | 65 | 6.2 (0.3–12) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 65 | 3.1 (−1.1–7.3) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 1 | 65 | 1.5 (−1.5–4.5) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 5 | 65 | 7.7 (1.2–14.2) |

| Tegumentary and visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 2344 | 0.6 (0.42–9.78) |

| Hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 2344 | 1.2 (0.76–1.64) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 2344 | 0.73 (0.39–1.07) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 725 | 2344 | 30.9 (29.03–32.77) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 6 | 2344 | 0.26 (0.04–0.48) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 85 | 2344 | 3.6 (2.85–4.35) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 26 | 2265# | 1.15 (0.72–1.58) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 10 | 144 | 6.9 (2.8–11.1) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 4 | 144 | 2.8 (0.1–5.5) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 3 | 144 | 2.1 (−0.2–4.4) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 42 | 144 | 29.2 (21.7–36.6) |

| Type of side effect . | Study type . | Number of events . | Treated patients . | Frequency (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | ||||

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 604 | 1439 | 42 (39.5–44.6) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 2 | 1439 | 0.14 (−0.05–0.33) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 29 | 1439 | 2 (1.28–2.72) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 17 | 1360# | 1.25 (0.66–1.84) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 6 | 79 | 7.6 (1.8–13.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 37 | 79 | 46.8 (35.8–57.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 905 | 1.5 (0.7–2.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 905 | 3.0 (1.9–4.1) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 905 | 1.9 (1–2.8) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 193 | 905 | 21.3 (18.7–24) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 4* | 905 | 0.4 (0–0.9) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 56 | 905 | 6.2 (4.6–7.8) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 8 | 381# | 2.1 (0.7–3.5) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 4 | 65 | 6.2 (0.3–12) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 65 | 3.1 (−1.1–7.3) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 1 | 65 | 1.5 (−1.5–4.5) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 5 | 65 | 7.7 (1.2–14.2) |

| Tegumentary and visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 2344 | 0.6 (0.42–9.78) |

| Hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 2344 | 1.2 (0.76–1.64) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 2344 | 0.73 (0.39–1.07) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 725 | 2344 | 30.9 (29.03–32.77) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 6 | 2344 | 0.26 (0.04–0.48) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 85 | 2344 | 3.6 (2.85–4.35) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 26 | 2265# | 1.15 (0.72–1.58) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 10 | 144 | 6.9 (2.8–11.1) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 4 | 144 | 2.8 (0.1–5.5) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 3 | 144 | 2.1 (−0.2–4.4) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 42 | 144 | 29.2 (21.7–36.6) |

Only patient treated intramuscularly are included.

*Fatal ventricular fibrillation.RCT: randomized controlled trials

Pooled side effects frequency in patients with leishmaniasis treated with parenteral pentamidine by type of studies and clinical form of leishmaniasis

| Type of side effect . | Study type . | Number of events . | Treated patients . | Frequency (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | ||||

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 604 | 1439 | 42 (39.5–44.6) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 2 | 1439 | 0.14 (−0.05–0.33) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 29 | 1439 | 2 (1.28–2.72) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 17 | 1360# | 1.25 (0.66–1.84) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 6 | 79 | 7.6 (1.8–13.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 37 | 79 | 46.8 (35.8–57.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 905 | 1.5 (0.7–2.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 905 | 3.0 (1.9–4.1) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 905 | 1.9 (1–2.8) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 193 | 905 | 21.3 (18.7–24) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 4* | 905 | 0.4 (0–0.9) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 56 | 905 | 6.2 (4.6–7.8) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 8 | 381# | 2.1 (0.7–3.5) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 4 | 65 | 6.2 (0.3–12) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 65 | 3.1 (−1.1–7.3) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 1 | 65 | 1.5 (−1.5–4.5) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 5 | 65 | 7.7 (1.2–14.2) |

| Tegumentary and visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 2344 | 0.6 (0.42–9.78) |

| Hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 2344 | 1.2 (0.76–1.64) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 2344 | 0.73 (0.39–1.07) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 725 | 2344 | 30.9 (29.03–32.77) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 6 | 2344 | 0.26 (0.04–0.48) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 85 | 2344 | 3.6 (2.85–4.35) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 26 | 2265# | 1.15 (0.72–1.58) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 10 | 144 | 6.9 (2.8–11.1) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 4 | 144 | 2.8 (0.1–5.5) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 3 | 144 | 2.1 (−0.2–4.4) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 42 | 144 | 29.2 (21.7–36.6) |

| Type of side effect . | Study type . | Number of events . | Treated patients . | Frequency (CI 95%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegumentary leishmaniasis | ||||

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 0 | 1439 | 0.0 (0–0) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 604 | 1439 | 42 (39.5–44.6) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 2 | 1439 | 0.14 (−0.05–0.33) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 29 | 1439 | 2 (1.28–2.72) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 17 | 1360# | 1.25 (0.66–1.84) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 6 | 79 | 7.6 (1.8–13.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 2 | 79 | 2.5 (−0.9–6) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 37 | 79 | 46.8 (35.8–57.8) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 905 | 1.5 (0.7–2.4) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 905 | 3.0 (1.9–4.1) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 905 | 1.9 (1–2.8) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 193 | 905 | 21.3 (18.7–24) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 4* | 905 | 0.4 (0–0.9) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 56 | 905 | 6.2 (4.6–7.8) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 8 | 381# | 2.1 (0.7–3.5) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 4 | 65 | 6.2 (0.3–12) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 2 | 65 | 3.1 (−1.1–7.3) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 1 | 65 | 1.5 (−1.5–4.5) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 5 | 65 | 7.7 (1.2–14.2) |

| Tegumentary and visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

| Type of side effect | Study type | Number of events | Treated patients | Frequency (CI 95%) |

| Renal toxicity | RCT and observational | 14 | 2344 | 0.6 (0.42–9.78) |

| Hyperglycemia | RCT and observational | 27 | 2344 | 1.2 (0.76–1.64) |

| Irreversible diabetes | RCT and observational | 17 | 2344 | 0.73 (0.39–1.07) |

| Subjective complaints | RCT and observational | 725 | 2344 | 30.9 (29.03–32.77) |

| Arrythmia | RCT and observational | 6 | 2344 | 0.26 (0.04–0.48) |

| Mild cardiac toxicity | RCT and observational | 85 | 2344 | 3.6 (2.85–4.35) |

| Muscular aseptic abscess | RCT and observational | 26 | 2265# | 1.15 (0.72–1.58) |

| Renal toxicity | Case report/case series | 10 | 144 | 6.9 (2.8–11.1) |

| Reversible hyperglycemia | Case report/case series | 4 | 144 | 2.8 (0.1–5.5) |

| Irreversible diabetes | Case report/case series | 3 | 144 | 2.1 (−0.2–4.4) |

| Subjective complaints | Case report/case series | 42 | 144 | 29.2 (21.7–36.6) |

Only patient treated intramuscularly are included.

*Fatal ventricular fibrillation.RCT: randomized controlled trials

Clinical Trials, Prospective and Retrospective Studies

Tegumentary leishmaniasis

We retrieved 27 studies reporting data on 3019 patients with TL of which 1945 treated with PI. Only one study was on ML, while the remaining were on CL.

The main characteristics of studies like design, inclusion criteria, outcome definition, follow-up, gender and age of patients, species of leishmania and state of immunosuppression, are reported in Supplementary Table S1 and S2. Among the 27 selected studies, cure criteria were significantly different among the studies included. For CL most common definition was ‘complete re-epithelization of lesions’ (13), ‘complete healing of all ulcers’ (six), ‘absence of parasites in lesion smear samples’ (three), while for four studies was not reported. In 24 studies, PI was used as a first-line treatment, in two studies as a second-line treatment, and in one combined with miltefosine.

The most common follow-up timing was 6 months, but several studies used three and 12 months, and in certain case 1.5 or 18 months (median 6, IQR, 3–12). For five studies, data on the timing of follow-up were not reported.

The median population age was 31 years (IQR, 28–35); in eight studies, age was not reported. A clear predominance of male gender was evident: 1544 male patients (82.6%) and 277 females (14.8%); in seven studies gender was not reported. Of these studies, 26 were made in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and one in a high-income country (HIC). Only two studies reporting a total of three patients were on the treatment of immunocompromised subjetcs.17,23

Species of leishmania involved was reported in 19 papers, with five papers reporting more than one leishmania species. In detail, L. guyanensis was reported in 12 studies, L. braziliensis in eight, L. naiffi, L. mexicana and L. panamensis in two papers each, L. shawi, in one. In one article from Ethiopia, the most likely species involved was L. aethiopica.101

The dosage and treatment schedules are presented in Supplementary Table S3. In 22 papers, the drug was administered intramuscularly and in one intravenously, in one study both ways and in three papers was administered intralesionally.25–27

In studies with PI administered through parenteral route, therapeutic schemes ranged from 2 mg/kg/die to 7 mg/kg/die (median 4, IQR, 4–4) for each dose and 7 mg/kg to 48 mg/kg of total dose (median 12, IQR, 8–16). Treatment duration ranged from one to 84 days (median 6, IQR, 3–14). In 16 studies the drug was administered every 48 h, in three studies once a week, in three studies once every 72 h, in one study at daily dosage, in two studies single-dose schedule was used.

Overall, the pooled cure rate reported in studies using parenteral pentamidine was 1533/1945 (78.8%; CI 95%, 76.9–80.6). Among 1533 initially cured patients, 45 (2.9%; CI 95%, 2.1–3.7) relapsed after the initial cure.

Through a subgroups analysis we found in patients treated with a dose ≤ 8 mg/kg (total dose) a pooled cure rate was 452/582 (77.7%; CI 95%, 74.3–81.5), in patients treated with a dose > 8 mg/kg (total dose) pooled cure rate of 1081/1363 (79.3%; CI 95%, 77.1–81.4), the differences calculated through chi-square test were not significant (P = 0.415). Rate of relapse was 9/582 (1.5%; CI 95%, 0.5–2.5) and 36/1363 (2.6%; CI 95%, 1.8–3.4) in the group treated with total dose ≤ 8 mg/kg and >8 mg/kg, respectively, the differences calculated through chi-square test were not significant (P = 0.141).

In studies with intralesional PI, the administration dose was always 120 μg/mm2 every 48 h, total dose ranged from 360 μg/mm2 to 720 μg/mm2. Treatment duration was 5 days. Overall, the pooled cure rate reported was 103/130 (79.2%; CI 95%, 72.2–86.2). No case of relapses were reported.

The summarized cure rates concerning studies on TL are shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Visceral leishmaniasis

We retrieved 10 studies reporting data on 1136 patients with VL of which 950 treated with PI.

The main characteristics of studies like design, inclusion criteria, outcome definition, follow-up, gender and age of patients, species of leishmania and state of immunosuppression, are reported in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6.

For VL outcome definitions were even more variable: ‘Reduction of spleen and liver size and normalization of blood count’ was one of the most common used (three papers), in the older articles was also used ‘disappearance of parasites from spleen or bone marrow aspirate’ (three papers); another was ‘absence of clinical signs and symptoms’ (four papers). In three studies only PI was used as first-line treatment; in the remaining seven was used after antimonials treatment failure. In two papers PI was combined with sodium stibogluconate and in another one with allopurinol.

Follow-up reported for patients was of 6 or 12 months (median 6, IQR, 6–12), for three papers was not described.

The overall median age of patients was 19 years (IQR, 18–25), three papers didn’t report detailed age of people included. Males were 666 (70.1%) and female 270 (28.4%); in two studies, gender was not registered. Of note, no immunocompromised nor HIV infected were described. All of these studies were made in LMICs.

Nine out of 10 studies were from India where L. donovani is endemic, while one study was from China where several leishmania species are endemic.102 There were no studies from the Mediterranean basin nor from Latin America where L. infantum is endemic. Therapeutic dosage varied from 2 to 5 mg/kg/die (median 4, IQR, 3–4) for each dose; cumulative dose ranged from 8, to 88 mg/kg of total dose (median 56 mg/kg, IQR, 15–80). Treatment duration ranged from 10 to 91 days (median 20, IQR, 10–40). In four studies, PI was administered intravenously and in five intramuscularly; in the remaining two articles, both administration methods were used. Six studies administered a dose every 48 h, two once every 72 h, 1 daily dosage, 1 used a single dose schedule. The therapeutic schedules are presented in Supplementary Table S7.

Overall pooled cure rate reported in studies was 806/950 (84.8%, CI 95%, 82.6–87.1%). The pooled cure rate in studies in which PI was used as second-line therapy was 673/750 (89.7%; CI 95%, 87.6–91.9%). The relapse rate after the cure was reported in eight papers. Among 846 treated patients, 114 (13.5%; CI 95%, 11.2–15.8%) relapsed. The summarized cure rates are shown in Supplementary Table S8.

Adverse drug reaction

Side effects were, in general, poorly described. Only 23 studies reporting data on 2344 patients mentioned them (Supplementary Table S17). Many authors just reported the absence of severe adverse drug reactions. Most relevant side effects were the following: subjective complains in 48.4% (CI 95%, 45.7–51.1), muscular aseptic abscess following intramuscular injection in 2.3% (CI 95%, 1.4–3.3%), renal toxicity in 0.8% (CI 95%, 0.4–1.2%), neuropathy 3.6% (CI 95%, 1.8–5.4), reversible hyperglycemia in 1.5% (CI 0.9–2%), irreversible diabetes in 0.9% (CI 95%, 0.5–1.4%), arrhythmia 0.3% (0.1–0.6%) and mild cardiac toxicity 4.7% (CI 95%, 3.7–5.6%). On note, in four cases, fatal ventricular fibrillation and three of rhabdomyolysis were reported in patients with VL and TL, respectively. In TL studies through a subgroups analysis we found in patients treated with a dose ≤ 8 mg/kg (total dose) a pooled adverse events rate was 65/393 (16.5% CI 95%, 12.1–20.9). In patients treated with a dose > 8 mg/kg (total dose) adverse events rate of 308/1170 (26.3%; CI 95%, 23.4–28.8). The differences calculated through chi-square were test statistically significant (P = 0.000082).

Case Report/Case Series

Tegumentary leishmaniasis

We retrieved 18 case reports and nine case series reporting data on 140 patients with TL of which 137 treated with PI. All patients were affected by CL (115 by New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (NWCL) and 22 by OWCL), while no muco-cutaneous were retrieved. The main characteristics of studies like design, inclusion criteria, outcome definition, follow-up, gender and age of patients, species of leishmania and immunocompromised, are reported in Supplementary Tables S9 and S10.

Sixty-five of them were male (47.4%) and 25 females (18.2%). In for four studies (34.4%) patient's gender was not reported. The median population age was 42 (IQR, 24–50): in four studies, age was not reported. Of these studies, 20 were made in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and seven in high-income countries (HICs).

Concerning leishmania species L. braziliensis was the causative agent in five reports (five patients); L. guyanensis, L. amazonensis, L. mexicana in two paper each (seven, seven and four patients respectively); L. naiffi and L. panamensis in only one paper each (three and one patients respectively). L. major and L. infantum were found in three reports each (six and four patients respectively), L. tropica and L. donovani in only one each (two and one patient, respectively). In one paper from Ethiopia, the most likely species involved was L. aethiopica.67

Six articles reporting data on 70 patients did not specify the species of leishmania.

The PI's dose ranged from 3 to 7 mg/kg/die median (4) and IQR (4–4) were similar in reports of NWCL and OWCL. Cumulative dose ranged from 8 mg/kg to 136 mg/kg total dose; for NWCL median cumulative dose was 24 mg/kg (IQR, 10–38), for OWCL median was 14 mg/kg (IQR, 8–50). Three studies did not report corrected body weight dose.55,57,67 In 17 studies, PI was used as a first-line treatment (in two cases combined to other drugs); in the remaining 10 papers was used as a second-line treatment after antimonials regimen failure.

In NWCL, 14 articles had a therapeutic schedule with a dose every 48 h, three had a daily regimen, and two had administration at every 72 and 96 h, respectively. OWCL, in three papers, were administered a dose every 72 h; in two papers, one dose every 48 h and the remaining two a daily and a weekly administration, respectively.

Regarding the administration route, in 12 reports about NWCL PI was used intramuscularly, in five reports intravenously, in one using both intramuscular and intravenous route and in one case was not reported. In OWCL PI was administered in all cases, except one, through the intramuscular route. The therapeutic schedules are presented in Supplementary Table S11.

The overall cure rate in patients treated with PI reported in case reports/case series was 110/115 (95.7%, CI 95%, 91.9–99.4%) for NWCL and 17/22 (77.3%; CI 95%, 59.8–94.8) for OWCL. The relapse rate after the cure was reported in 4 out of 8 (50%) papers for OWCL and in 18 papers out of 19 (94.7%) for NWCL. Among 115 treated patients with NWCL, 7 (6.1%; CI 95%, 1.7–10.5%) relapsed; no relapse cases were recorded among patients with OWCL. The summarized cure rates are shown in Supplementary Table S12.

Visceral leishmaniasis

We retrieved 21 case reports and three case series reporting data on 106 patients with VL of which 76 patients were treated with PI. The main characteristics of studies like design, inclusion criteria, outcome definition, follow-up, gender and age of patients, species of leishmania and immunosuppression status, are reported in Supplementary Tables S13 and S14.

The median age was 35 years (IQR, 17–43); two papers did not report the age. Gender was known in 66 patients, of which 45 (80.3%) were male. A total of 12 out of 76 (15.8%) patients were immunocompromised. Of these studies, 10 were made in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and 14 in high-income countries (HICs).

About leishmania species, L. donovani was found in eight studies, L. infantum in three studies, in the remaining thirteen, it was not specified (however, eight of these studies were from L. infantum endemic areas).

Therapeutic dosage varied from 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/die (median 4, IQR, 4–4) for each dose; cumulative dose ranged from 36 mg/kg to 468 mg/kg (median 60, IQR, 44–102); for five studies was not possible to understand cumulative dose. Treatment duration ranged from 2 to 540 days (median 21, IQR, 13–35). In six articles, PI was administered intramuscularly, in fifteen intravenously; in three papers, the route of administration was not reported.

In six studies PI was administered every 48 h, in 12 studies the drug was administered every 24 h; in the remaining studies a different schedule was used. The therapeutic schedules are presented in S15.

Information on clinical outcome was available for most patients (75 of 76), and cure was achieved in 68 of 75 patients (90.7%; CI 95%, 84.1–97.3%). PI was used as a first-line treatment in three studies only (in one of which was used in combination with antimonials); in the remaining 21 papers it was used as a second-line treatment after antimonials regimen failure.

Information concerning relapse after cure was reported in 18 out of 24 papers (75%). Among 75 treated patients, 4 (5.3%; CI 95%, 0.2–10.4%) relapsed. The summarized cure rates are shown in Supplementary Table S16.

Adverse drug reaction

In 28 case reports/case series reporting data on 144 patients (65 with VL and 79 with TL) side effects are evaluated (Supplementary Table S18). Most frequently reported side effects were subjective complains in 29.2% (CI 95%, 21.7–36.6%), renal toxicity in 6.9% (CI 95%, 2.8–11.1%), reversible hyperglycemia in 2.8% (CI 0.1–5.5%) and irreversible diabetes in 2.1% (CI 95%, 0.2–4.4%).

Discussion

Pentamidine is a well know anti-leishmanial drug, and it was first synthesized in the late 1930s.103 The drug was initially used for the treatment of VL before 1950s68; then, it was taken into account to treat resistant form of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the late 1970s. The drug was re-evaluated and commercialized in its actual isethionate form in 1984.104 PI, an aromatic diamidine, has antifungal and antiprotozoal activity. The mechanism of action of PI is not well understood and appears to vary among different microorganisms. PI likely critically interferes with DNA function, RNA and protein biosynthesis.105

Because of the availability of other therapeutic options, and potentially severe side effects PI has been practically abandoned in recent years to treat leishmaniasis.

However, according to most guidelines, it is still the first-line option for L. guyanensis and L. panamensis. Moreover, it is recommended by the WHO for diffuse CL caused by L. aethiopica.106 While there are only a few studies on pentamidine for L. aethiopica, (some of them not retrieved in our review), available data seem to indicate a relatively good efficacy, although relapse has been commonly observed after pentamidine discontinuation.107

According to the majority of guidelines, it is still the first-line option for L. guyanensis and L. panamensis.

In our review, we found that the drug provides quite a high cure rate. Briefly, according to data from RCTs and observational studies PI has a cure rate of 77.8% (CI 95%, 76.9–80.6) for TL and 84.8% (CI 95%, 82.6–87.1%) for VL, while according to case reports and case series the cure rates are 92.7% (88.3–97.1%) for TL and 90.7% (84.1–97.3%) for VL. The higher cure rate found in the case report and case series is probably related to reporting bias.

We calculated the different cure rate and adverse events (in RCT, prospectic and observational studies) among lower total dose (≤8 mg/kg) and higher total dose (>8 mg/kg), but on the basis of the current literature we didn’t find any significant difference. We didn’t perform this subgroup analysis for VL because schedule used were too heterogeneous.

Data on the cure rate for VL from RCTs and observational studies come primarily from studies in which PI was used as second-line drugs highlighting a good treatment response in recurrent and refractory VL cases.

Our review allows us to perform a direct comparison between PI and other drugs.

Cure rate of PI are comparable to those reported for other drugs. For example, according to a systematic review of literature pentavalent antimonials have a cure rate of 80% in NWCL and ML.108 Other studies regarding these drugs, reported different cure rates according to the leishmania species: L. mexicana 89% (26%–100%),109,110 L. amazonensis 100%,111 L. braziliensis 78% (67%–87%),112,113 L. peruviana 74% (40%–65%)112,113 and L. panamensis 75% (63%–85%).113,114

According to a systematic review of literature, miltefosine showed an overall cure rate of 67% for NWCL,115 ranging from 90% to 50% based on species and geographic area which it is used116,117; while another study showed lower efficacy rate independently from the leishmania species.118

Liposomal amphotericin B has a reported cure rate of 85% for CL,119 88% for ML120 and 89% for VL.121

An important point that require further studies is that treatment of VL in immunocompromised patients that frequently develop relapse, poor response to repeated first-line treatment and cumulative iatrogenic toxicity.9 Therefore, also in this population, PI might play a role.

The cure rate with PI based on data from in case report was lower for OWCL compared to NWCL (77.3% vs. 95.7%). Efficacy for the various Leishmania species was difficult to establish because it was not specified accurately in the majority of studies. However, among 97 cases of L. braziliensis the cure rate was 57.7%, among the 199 L. panamensis cases was 82.9% and among the 623 L. guyanensis cases was 75.9% (as shown in Supplementary Tables S2 and S4). Based on only a few and small studies cure rate for L. naiffi was 50% and for L. mexicana 75%.16,19,38 The large majority of data were from the male population probably because many articles are referred to armies primarily composed of men.

Few data, most coming from case reports, were available on efficacy in patients with VL caused by L. infantum. Similarly, very few data were available from ML (one study only) and OWCL cases.

A wide set of treatment schedules and dosages has been reported. However, the total dose is quite similar in RCTs and observational studies and in case report and case series in the two main clinical form of the disease. In particular, for VL the total dose reported was most commonly 56–60 mg/kg and for TL 12–24 mg/kg.

Based on these findings, we believe that standard dosage suggested in guidelines (Table 1) are usually effective and can be used in the majority of cases; however, in selected patients the treatment can be prolonged and the total dose administered increased to achieve a satisfactory clinical response.

Because one of the main concerning points on the use of PI is the safety profile, we collected data on side effects. Data were available for ~2000 patients; however, during the study analysis and data extraction, lack of a proper description of adverse events was commonly encountered, so these results have to be interpreted with caution. Considering all type of studies, the most concerning side effects reported were four cases of fatal ventricular fibrillation (all in patients with VL), 20 cases of irreversible diabetes (18 in patients with VL and 2 in patients with TL), 25 cases of muscular aseptic abscess following intramuscular administration (17 in patients with TL and 8 in a patient with VL). The different type of side effects observed in patients with VL and TL is likely related to the route of administration (intramuscular route most commonly used in TL patients), to the higher dosage used in VL patients and possibly to the worst general condition of VL patients compared to TL patients. Some authors suggest that side effects such as diabetes occur in case of total dose over 1 g, usually required in VL rather than TL.122 Additional reported side effects of pentamidine are hypoglycemia and hypotension.123

In two RCT made for African Trypanosomiasis the overall rate of ADR in patients treated with pentamidine was 92.7%124 and 93%125 respectively; however the majority of these side effects were mild and self-reported; in fact, regarding specific ADR, regarding specific ADR, rate of glucose metabolism disorder was 15.3%, acute kidney damage was 3.6% and mild cardiovascular toxicity (for example hypotension) was 56.9%.124

It is also important to note that TL is notoriously a disease that affects travellers, especially those who travel to Central and South America.6 Although most of the studies on pentamidine have been made on endemic areas, there are several experiences with drug in the travel medicine context, as it is generally available in temperate countries representing a valuable treatment option also in these setting especially in complex relapsing cases (alone or in combination with other drugs)44,47,126 or in patients that cannot receive first-line drugs.127

To sum up, our review shows that PI is associated with a cure rate comparable to first-line drugs in both CL and VL cases, including VL cases not responding or relapsing after first-line treatment. The majority of evidence is available for NWCL and VL caused by L. donovani, while few data are available for ML, OWCL and LV caused by L. infantum.

The most important limitation of our systematic review is that the majority of studies are non-randomized and in general of low quality; furthermore, a lot of them were realized in a period in which scientific methodology was flawed, in fact, often the methods were not clarified, clinical and demographic data were not available or presented only through tables, and outcome and results were difficult to extrapolate making difficult to made clean comparison.

Another limitation is that our search strategy included only articles having word ‘pentamidine’ in title or abstract. For this reason, some articles not focused on this drug but reporting some cases of leishmaniasis treated with pentamidine could be not included in the analysis.

In conclusion, PI may still have a role in the treatment of any form of human leishmaniasis when the first-line option has failed or in patients who cannot tolerate other drugs for any reason. In difficult cases, PI can also be considered as a component of a combination treatment regimen. As positive elements about PI, we want to underline that is a very cheap drug (in contrast with miltefosine or liposomal amphotericin B). In some setting such as Italy, it is usually available, unlike antimonials and paromomycin, since it is commonly used via aerosol for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis in AIDS patients allergic to sulphonamides.

Funding

This article has been supported by funds of the ‘Ministry of Education, University and Research (Italy) Excellence Departments 2018–2022’ Project for the Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy.

Conflict of interest: All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors contributions

M.P. and F.L. performed literature search, data extraction, data analysis and manuscript drafting; A.B. critically reviewed the manuscript; and L.Z. carried out conceptualization, manuscript writing and revision.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study does not need ethics committee approval.

References

Panel on Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV.