-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Caroline de Lorenzi, Sandrine Quenan, Lionel Fontao, Dermatophilus congolensis dermatitis in a traveller from Thailand, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 6, August 2021, taab017, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taab017

Close - Share Icon Share

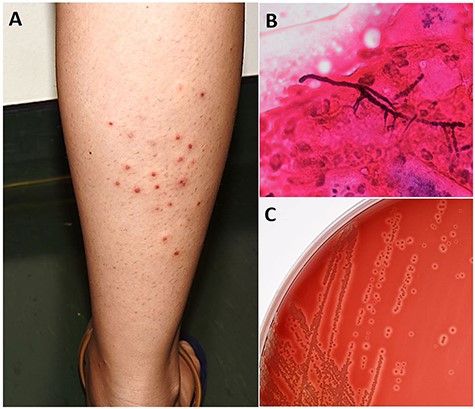

A 28-year-old woman without past medical history presented at the dermatology clinic of the Geneva University Hospitals (Switzerland) with a 4-day history of skin rash localized on both legs and extending to the flanks. Skin lesions appeared during a trip in Thailand in July 2019 from which she had returned a week ago before consulting. Activities in Thailand included swimming in rivers, riding elephants and sightseeing tours. Another member of the group also had few similar cutaneous lesions on the legs. The patient reported to wear short clothes during her journey, including elephant riding. Clinical findings showed papulo-pustular skin lesions distributed on both legs (Figure 1A), thighs and flanks. Gram-positive branching filaments with septations and coccoid cells, which have a ‘stacked coins’ appearance were found in skin smear (Figure 1B). Beta-haemolytic colonies were isolated in culture on blood agar (Figure 1C) and identified as Dermatophilus congolensis by 16S ribosomal DNA gene sequencing.

(A) Papulo-pustular skin lesions distributed on the right leg. (B) Gram-positive branching filaments with septations and coccoid cells. (C) Beta-haemolytic colonies isolated in culture on blood agar.

After a 1-week course of doxycycline at dosage of 100 mg once a day, associated with local antiseptic skin care (aquaeous chlorexidine), skin rash resolved leaving scaly papules and then post-inflammatory pigmented macules.

Dermatophilus congolensis is an unusual aerobic (facultative anaerobic) gram-positive bacteria in the order Actinomycetales. It has the ability to form filamentous structures evolving to coccoid forms.1,2 It has a worldwide distribution, but is mostly found under tropical areas or humid climates, and poor hygiene conditions represent a risk factor.3 Dermatophilus congolensis was originally described by van Saceghem in 1915 in Congo as a dermatitis in cattle.2 It is known as an animal pathogen, responsible for dermatophilosis, a skin disease mainly seen in cattle (goats, sheep, cows and horses), but it also affects other domestic and wild animals (cats and deer, for example).1–3 Dermatophilosis rarely affects humans, but can be transmitted by contact with infected animal.2,3 To date, few cases of human skin infection, particularly in travellers riding elephants in Thailand, as our patient, have been reported.3,4 The mechanism of transmission is unclear, but pre-existing dermatosis or cutaneous trauma (leg shaving) seems to play a role.4

The human disease has a wide clinical spectrum with aspecific lesions such as papules, pustules, desquamative eczema, folliculitis, subcutaneous nodules, intertriginous lesions with maceration, pitted keratolysis and fissuring, and more rarely, involvement of the oesophagus and oral mucosa.1,2,5 Diagnosis is orientated by microscopic features and confirmed by cultures.1

The disease seems to be self-limiting and can resolve completely without treatment.1,3 Various treatment regimens have been reported such as topical gentamycin or systemic antibiotics (ampicillin, intramuscular streptomycin, cefadroxil), nevertheless to date, there are no recommendations to guide clinicians.1,3,5

Because D. congolensis dermatitis has a wide clinical spectrum and is self-limiting, it is probably underdiagnosed. The prevalence among European travellers is probably more elevated than the few cases reported in the literature. Clinicians should be encouraged to deepen travellers’ activities during anamnesis and think about this aetiology. Moreover, travellers to Thailand should be informed during the pre-travel consultation and strongly encouraged to wear long trousers for elephant’s rides.

Authors’ Statement

C.d.L., S.Q. and L.F. stated no financial interests or connections, direct or indirect, or other situations that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or the conclusions, implications or opinions stated—including pertinent commercial or other sources of funding for the individual author(s) or for the associated department(s) or organization(s), personal relationships or direct academic competition.

Authors’ Contribution

C.d.L. contributed towards literature search, data collection, figures, interpretation and manuscript. S.Q. contributed towards literature search and manuscript. L.F. contributed towards data collection, interpretation, literature search and manuscript.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.