-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Loes Verdoes, Floriana S Luppino, Prof Jacco Wallinga, Prof Leo G Visser, Delayed rabies post-exposure prophylaxis treatment among Dutch travellers during their stay abroad: a comprehensive analysis, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 3, April 2021, taaa240, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa240

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

After an animal-associated injury (AAI) in rabies-endemic regions, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is needed to prevent infection.1,2 PEP consists of rabies vaccinations (RV) and in some cases also additional rabies immune globulins (RIG). Not always PEP medication, and RIG in particular, is accessible. Along with an increased number of exposure notifications among Dutch travellers, this might lead to treatment delay and thus to increased health risks. Until now, research mainly focused on factors associated with exposition, but none on which factors are associated with PEP delay. This study aimed to identify which general sample characteristics are associated with PEP delay while being abroad.

A quantitative retrospective observational study was conducted. The study population consisted of insured Dutch international travellers who actively contacted their medical assistance company (2015–2019) because of an animal-associated injury (AAI) (N = 691). The association between general sample characteristics and delay of different PEP treatments was studied using survival analysis.

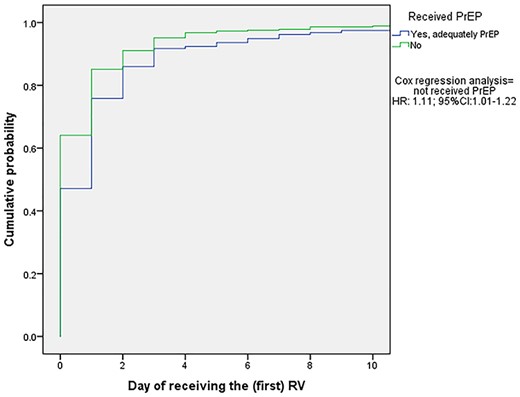

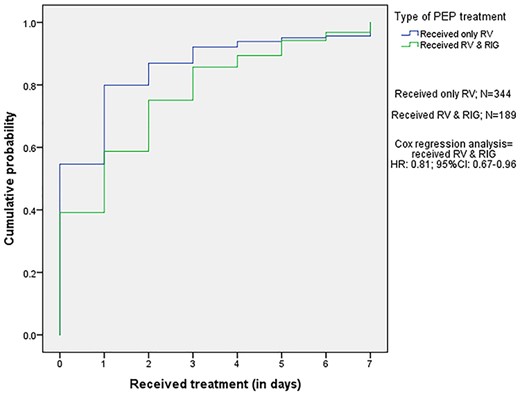

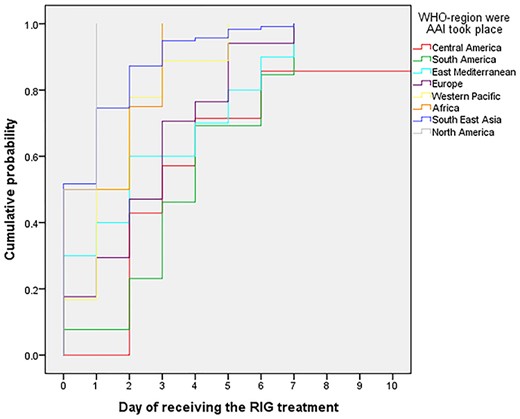

Travellers without pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) had an increased hazard, and therefore a shorter delay, for receiving their first RV as compared to travellers with PrEP (HR:1.11, 95%CI:1.01–1.22). The travellers needing both RV and RIG had a decreased hazard, and therefore a longer delay, as compared to travellers only needing RV (HR:0.81, 95%CI:0.67–0.96). General sample characteristic associated with RIG administration delay was travel destination. Travellers to Central and South America, East Mediterranean and Europe had a decreased hazard, and therefore a longer delay, for receiving RIG treatments relative to travellers to South East Asia (HR:0.31, 95%CI:0.13–0.70; HR:0.34, 95%CI:0.19–0.61; HR:0.46, 95%CI:0.24–0.89; HR:0.48, 95%CI:0.12–0.81, respectively).

Our results suggest that the advice for PrEP should be given based on travel destination, as this was found to be the main factor for PEP delay, among travellers going to rabies-endemic countries.

Introduction

Rabies is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by the rabies virus (RABV).1,3 Once clinical manifestations of rabies become apparent, the disease is almost invariably fatal.2 The estimated annual total number of human deaths amounts to 59 000, in more than 150 countries.4,5

After an animal-associated injury (AAI) in a rabies-endemic region, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) treatment is needed to prevent disease.1,2 PEP consists of rabies vaccinations (RV) and in some cases additional rabies immune globulins (RIG).1,3,6,7 In accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, PEP should be administered as soon as possible, preferably within 24 h after the AAI. This is the case particularly for RIG, as it is considered, next to thorough wound washing, the first line of defence against RABV infection.1,2,6

In high-income countries where canine rabies is no longer endemic, most human rabies cases have been reported among international travellers.8 Between 1990 and 2010, 42 imported rabies cases have been reported in Europe, the United States and Japan.9 However, the number of travellers encountering an AAI is much higher with an estimated incidence of 0.4% per month of stay,10,11 or even higher in countries like Thailand.12 Farnham et al. reported that among travellers visiting Thailand, 14.7% of all health events consisted of an AAI, and the risk of animal contact increased cumulatively over the course of the trip.13 Compared to other travellers, young adult backpackers and travellers ‘visiting friends or relatives’ (VFR), travelling to North-Africa and South East Asia, have an increased risk for encountering an AAI compared to other travellers.10–12,14–17 The WHO recommends these travellers to receive pre-exposure RV (PrEP) before going to rabies-affected countries, in particular when planning outdoor activities, going to rural areas or travel for more than three months.6,18,19 Despite these recommendations, travel clinic protocols do not know international consensus on the pre-travel rabies advice and more than 90% of the travellers who had an AAI had not received PrEP.10,15,20–22 In addition, most travellers seem to lack awareness with regard to the risk of rabies exposure in endemic region.12,22,23

One of the major problems that these unvaccinated travellers encounter after an AAI is the scarce availability of PEP.24,25 Especially RIG is difficult to obtain in low- and middle-income rabies-endemic countries, such as the South/West Pacific Islands and Tropical South America.4,24,26 Without pre-travel PrEP, a more extensive post-exposure RV scheme is required, which, along with the limited availability of RIG, results in treatment delay.11,12,25,27 As a consequence, approximately 70–85% of travellers do not receive adequate wound care and treatment after an AAI,19,27 and only 10% of all AAI notifications receive RIG in the country of exposure.10,19,21 A more recent and prospective study showed that 3 of the 8 travellers who sought medical help after an AAI received PEP in the country of exposure.17 Unfortunately, none of the above-mentioned studies reported information on PEP delay. PEP delay may lead to an unnecessary increased health risk among travellers, given the fatal outcome in case of infection.2,4,6,10,25,27 In addition, the lack of RIG or RV creates logistic problems and increased (indirect) costs, for example, in case of evacuation or repatriation of travellers to a health care centre where PEP treatment is available.4,6,21,25,27

Travellers who encounter an AAI frequently contact the emergency medical assistance centre of their health insurance company. Eurocross Assistance (ECA) (Leiden, the Netherlands) is one of the leading medical assistance organizations in the Netherlands for insured Dutch citizens with medical problems abroad, covering approximately 30% of the Dutch market.28,29 In 2018, ECA observed a 59% increase of AAI notifications (N = 316) from Dutch travellers compared to the preceding year (2017: N = 187).18,24 Previous research on rabies PEP focused on travellers who already had returned to their home countries, leading to possible recall bias.10,19 By investigating a population actively reporting an AAI to their medical assistance centre during their stay, a better and more accurate comprehension on the topic can be obtained. Gaining more insights on PEP delay and its risk factors might help in the pre-travel decision-making on the need of PrEP, and bring more awareness on the importance and advantages of PrEP, especially among travellers, such as the lifelong immunological protection and the need of only two booster RV in case of an AAI.23,30 Our study aimed to analyse the characteristics of travellers who reported an AAI to ECA, the circumstances around the AAI, the delay in PEP and the characteristics associated with a delayed PEP after an AAI.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a quantitative observational study using the ECA electronic database. Our study population consisted of insured Dutch international travellers who, while being abroad, actively contacted ECA because of an AAI (‘AAI notification’). Subjects were asked additional questions about the AAI, in order to be able to provide a proper medical treatment advice, according to WHO guidelines.1

Data collection

Individual case records of AAI notifications between December 2015 and February 2019 (N = 742) were included in the study after extraction from the ECA electronic database. Case records were excluded from the study if they did not include any information about the AAI (N = 51). This resulted in a final sample of 691 AAI notification files from the ECA database. After anonymization, relevant information from the individual files was transferred to a Castor database (Castor Electronic Data Capture, Amsterdam, the Netherlands).

The collected data used for the analyses were provided by the client and consisted of age, gender, country of AAI, travel duration, countries visited, purpose of travel, previously received PrEP, information on the AAI (physical localization, wound exposure category, animal) and medical care given abroad [advised PEP scheme (WHO-Zagreb or WHO-Essen)2 and day of administrated PEP]. Based on the received information, such as WHO exposure category and PrEP status, the medical doctors of ECA gave the PEP advice. In case of doubt, experts of the ‘National Institute of Health and Environment’ were consulted.

Additional variables such as time between departure and the AAI, corresponding WHO region of the country, time between the AAI and the notification and delay of PEP were also based on contact(s) between ECA and the client.

A PEP treatment was considered delayed if the administration was given more than 24 h after the AAI. The outcome variable ‘PEP delay’ was measured in days; the first 24 h after the AAI was set at ‘day 0’.

The Medical Ethics Committee (METC Leiden-Den Haag-Delft) approved the study as not subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).31

Kaplan–Meier curve for receiving the first dose of RV in days after an AAI according to pre-travel PrEP (N = 527). The ‘no-PrEP’ group received their PEP 0.9 (1/1.11) times in days faster, compared to those who received PrEP. Abbreviations: PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; no-PrEP, traveller did not receive pre-travel pre-exposure prophylaxis; RV, rabies vaccinations; HR, hazard ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics version 24). Relevant sample characteristics were analysed using means and standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables and percentages for categorical variables.

First, the association between PrEP and PEP delay was analysed. This was only analysed for the population that required RV after an AAI, since travellers who required RIG by definition had not received PrEP before travel. Second, the association between PEP delay and requirement for RIG was analysed. Third, we identified determinants associated with a higher risk for PEP delay. All analyses were performed by using event history analysis: Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox regression analysis. The associations were considered statistically significant based on the 95% confidence interval (95%CI); P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

If an association between unvaccinated PrEP and PEP delay in RV was observed in the Kaplan–Meier curve/Cox regression, the analysis was repeated after further stratification according to PrEP and no-PrEP. Additionally, as difference in availability of RV and RIG has been described,24 the possibility of a different delay in treatment between RV and RIG was taken into consideration. Therefore, if the results of the Kaplan–Meier curves/Cox regression showed a difference in curves, all analyses were stratified by type of PEP (RV vs RIG).

Kaplan–Meier curves are frequently used to visualize survival analyses, and much less to express the results of an event history analysis. We feel a brief reading guide for our event history analysis/Kaplan–Meier curves is therefore appropriate. A Kaplan–Meier curve represents the time to a particular event, often survival. When comparing two treatments, the one with the highest probability of longer survival [a higher hazard ratio (HR)] is clinically the most favourable. In our study, however, the outcome measure was PEP delay in days. In our study, a higher HR means a higher risk of delay, which is clinically unfavourable. The lower the HR, the lower the risk of delay, and the more clinically favourable this is.

Results

General characteristics

Travellers’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. Travellers who received PrEP pre-travel were found to be younger (27 (±6.5) vs 31 (±13.2) years), were more likely to be female (61.8%), had a longer travel duration (median:58, IQR:89) and travelled more often to multiple countries (71.6%). Most AAIs occurred within the first month of travel and in > 75% of the cases occurred among the group that did not receive pre-travel PrEP. For all travellers, South East Asia was the WHO region with the most AAI notifications, followed by the Western Pacific, Europe and South America. The time between the AAI and the notification was in most cases within 24 h (PrEP:70.3% vs no-PrEP: more than 70%). Further details on the AAI are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

General characteristics of Dutch travellers who contacted their emergency medical assistance after encountering an animal-associated injury, stratified by pre-travel pre-exposure vaccination and type of post-exposure treatment

| . | Received PrEP . | Did not receive PrEP . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | RV (N = 165) . | RV (N = 389) . | RIG (N = 219) . |

| General sample characteristics | |||

| Age in (years) (mean, SD) | 27.0 (6.5) | 29.5 (13.2) | 30.5 (13.8) |

| Gender Male (n,%) Female (n, %) | 63 (38.2%) 102 (61.8%) | 178 (45.8%) 211 (54.2%) | 112 (51.1%) 107 (48.9%) |

| Travel duration in (days) (median, IQR) | 58.0 (89.0) | 23.0 (22.5) | 24.0 (24.0) |

| Travel in multiple countries Yes (n,%) No (n,%) | 63 (71.6%) 25 (28.4%) | 72 (40.4%) 106 (59.6%) | 43 (43.4%) 56 (56.6%) |

| Purpose of travel Holiday (n,%) Tour (n,%) Business (n,%) Study/internship (n,%) VFR (n,%) Resident (n,%) Volunteer work (n,%) Other (n,%) | 103 (62.8%) 46 (30.0%) 1 (0.6%) 8 (4.9%) 0 4 (2.4%) 2 (1.2%) 0 | 275 (71.4%) 78 (20.3%) 3 (0.8%) 14 (3.6%) 6 (1.6%) 0 6 (1.6%) 3 (0.8%) | 150 (69.4%) 46 (21.3%) 4 (1.9%) 5 (2.3%) 3 (1.4%) 1 (0.5%) 6 (2.8%) 1 (0.5%) |

| AAI notification (n,%) | |||

| AAI after departure Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 >1 month & ≤ 2 months > 2 months & ≤ 3 months > 3 months | 30 (18.2%) 32 (19.4%) 16 (9.7%) 13 (7.9%) 33 (20.0%) 15 (9.1%) 26 (15.8%) | 126 (32.4%) 97 (24.9%) 56 (14.4%) 30 (7.7%) 33 (8.5%) 17 (4.4%) 30 (7.7%) | 61 (27.9%) 54 (24.7%) 36 (16.4%) 17 (7.8%) 19 (8.7%) 11 (5.0%) 21 (9.6%) |

| Country of AAI (top 5) |

|

|

|

| AAI according to WHO regions South East Asia Western Pacific Europe South America East Mediterranean Africa Central America North America | 80 (48.5%) 40 (24.2%) 4 (2.4%) 21 (12.7%) 3 (1.8%) 12 (7.3%) 3 (1.8%) 2 (1.2%) | 237 (60.9%) 43 (11.1%) 32 (8.2%) 20 (5.1%) 22 (5.7%) 15 (3.9%) 13 (3.3%) 7 (1.8%) | 126 (57.5%) 21 (9.6%) 25 (11.4%) 16 (7.3%) 14 (6.4%) 4 (1.8%) 8 (3.7%) 5 (2.3%) |

| Time between AAI and notification Within 24 h After 24 h | 116 (70.3%) 49 (29.7%) | 272 (70.1%) 117 (29.9%) | 162 (74.0%) 57 (26.0%) |

| Delay of treatment (n,%) | |||

| No delay (day 0) Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 >Day 7 | 74 (47.1%) 45 (28.7%) 16 (10.2%) 9 (5.7%) 1 (0.6%) 2 (1.3%) 2 (1.3%) 8 (4.8%) | 237 (64.1%) 78 (21.1%) 22 (5.9%) 15 (4.1%) 6 (1.6%) 2 (0.5%) 1 (0.3%) 9 (2.7%) | 74 (39.2%) 37 (19.6%) 31 (16.4%) 20 (10.6%) 7 (3.7%) 9 (4.8%) 5 (2.6%) 6 (3.1%) |

| . | Received PrEP . | Did not receive PrEP . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | RV (N = 165) . | RV (N = 389) . | RIG (N = 219) . |

| General sample characteristics | |||

| Age in (years) (mean, SD) | 27.0 (6.5) | 29.5 (13.2) | 30.5 (13.8) |

| Gender Male (n,%) Female (n, %) | 63 (38.2%) 102 (61.8%) | 178 (45.8%) 211 (54.2%) | 112 (51.1%) 107 (48.9%) |

| Travel duration in (days) (median, IQR) | 58.0 (89.0) | 23.0 (22.5) | 24.0 (24.0) |

| Travel in multiple countries Yes (n,%) No (n,%) | 63 (71.6%) 25 (28.4%) | 72 (40.4%) 106 (59.6%) | 43 (43.4%) 56 (56.6%) |

| Purpose of travel Holiday (n,%) Tour (n,%) Business (n,%) Study/internship (n,%) VFR (n,%) Resident (n,%) Volunteer work (n,%) Other (n,%) | 103 (62.8%) 46 (30.0%) 1 (0.6%) 8 (4.9%) 0 4 (2.4%) 2 (1.2%) 0 | 275 (71.4%) 78 (20.3%) 3 (0.8%) 14 (3.6%) 6 (1.6%) 0 6 (1.6%) 3 (0.8%) | 150 (69.4%) 46 (21.3%) 4 (1.9%) 5 (2.3%) 3 (1.4%) 1 (0.5%) 6 (2.8%) 1 (0.5%) |

| AAI notification (n,%) | |||

| AAI after departure Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 >1 month & ≤ 2 months > 2 months & ≤ 3 months > 3 months | 30 (18.2%) 32 (19.4%) 16 (9.7%) 13 (7.9%) 33 (20.0%) 15 (9.1%) 26 (15.8%) | 126 (32.4%) 97 (24.9%) 56 (14.4%) 30 (7.7%) 33 (8.5%) 17 (4.4%) 30 (7.7%) | 61 (27.9%) 54 (24.7%) 36 (16.4%) 17 (7.8%) 19 (8.7%) 11 (5.0%) 21 (9.6%) |

| Country of AAI (top 5) |

|

|

|

| AAI according to WHO regions South East Asia Western Pacific Europe South America East Mediterranean Africa Central America North America | 80 (48.5%) 40 (24.2%) 4 (2.4%) 21 (12.7%) 3 (1.8%) 12 (7.3%) 3 (1.8%) 2 (1.2%) | 237 (60.9%) 43 (11.1%) 32 (8.2%) 20 (5.1%) 22 (5.7%) 15 (3.9%) 13 (3.3%) 7 (1.8%) | 126 (57.5%) 21 (9.6%) 25 (11.4%) 16 (7.3%) 14 (6.4%) 4 (1.8%) 8 (3.7%) 5 (2.3%) |

| Time between AAI and notification Within 24 h After 24 h | 116 (70.3%) 49 (29.7%) | 272 (70.1%) 117 (29.9%) | 162 (74.0%) 57 (26.0%) |

| Delay of treatment (n,%) | |||

| No delay (day 0) Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 >Day 7 | 74 (47.1%) 45 (28.7%) 16 (10.2%) 9 (5.7%) 1 (0.6%) 2 (1.3%) 2 (1.3%) 8 (4.8%) | 237 (64.1%) 78 (21.1%) 22 (5.9%) 15 (4.1%) 6 (1.6%) 2 (0.5%) 1 (0.3%) 9 (2.7%) | 74 (39.2%) 37 (19.6%) 31 (16.4%) 20 (10.6%) 7 (3.7%) 9 (4.8%) 5 (2.6%) 6 (3.1%) |

Abbreviations: PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; SD, standard deviation; IQR, inter-quartile range; VFR, visiting friends or relatives; AAI, animal-associated injury; ID, Indonesia; TH, Thailand; LK, Sri Lanka; VN, Vietnam; KH, Cambodia; MY, Malaysia; TR, Turkey; CO, Colombia; WHO, World Health Organization; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; RV, rabies vaccinations; RIG, rabies immune globulins; ECA, Eurocross Assistance.

General characteristics of Dutch travellers who contacted their emergency medical assistance after encountering an animal-associated injury, stratified by pre-travel pre-exposure vaccination and type of post-exposure treatment

| . | Received PrEP . | Did not receive PrEP . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | RV (N = 165) . | RV (N = 389) . | RIG (N = 219) . |

| General sample characteristics | |||

| Age in (years) (mean, SD) | 27.0 (6.5) | 29.5 (13.2) | 30.5 (13.8) |

| Gender Male (n,%) Female (n, %) | 63 (38.2%) 102 (61.8%) | 178 (45.8%) 211 (54.2%) | 112 (51.1%) 107 (48.9%) |

| Travel duration in (days) (median, IQR) | 58.0 (89.0) | 23.0 (22.5) | 24.0 (24.0) |

| Travel in multiple countries Yes (n,%) No (n,%) | 63 (71.6%) 25 (28.4%) | 72 (40.4%) 106 (59.6%) | 43 (43.4%) 56 (56.6%) |

| Purpose of travel Holiday (n,%) Tour (n,%) Business (n,%) Study/internship (n,%) VFR (n,%) Resident (n,%) Volunteer work (n,%) Other (n,%) | 103 (62.8%) 46 (30.0%) 1 (0.6%) 8 (4.9%) 0 4 (2.4%) 2 (1.2%) 0 | 275 (71.4%) 78 (20.3%) 3 (0.8%) 14 (3.6%) 6 (1.6%) 0 6 (1.6%) 3 (0.8%) | 150 (69.4%) 46 (21.3%) 4 (1.9%) 5 (2.3%) 3 (1.4%) 1 (0.5%) 6 (2.8%) 1 (0.5%) |

| AAI notification (n,%) | |||

| AAI after departure Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 >1 month & ≤ 2 months > 2 months & ≤ 3 months > 3 months | 30 (18.2%) 32 (19.4%) 16 (9.7%) 13 (7.9%) 33 (20.0%) 15 (9.1%) 26 (15.8%) | 126 (32.4%) 97 (24.9%) 56 (14.4%) 30 (7.7%) 33 (8.5%) 17 (4.4%) 30 (7.7%) | 61 (27.9%) 54 (24.7%) 36 (16.4%) 17 (7.8%) 19 (8.7%) 11 (5.0%) 21 (9.6%) |

| Country of AAI (top 5) |

|

|

|

| AAI according to WHO regions South East Asia Western Pacific Europe South America East Mediterranean Africa Central America North America | 80 (48.5%) 40 (24.2%) 4 (2.4%) 21 (12.7%) 3 (1.8%) 12 (7.3%) 3 (1.8%) 2 (1.2%) | 237 (60.9%) 43 (11.1%) 32 (8.2%) 20 (5.1%) 22 (5.7%) 15 (3.9%) 13 (3.3%) 7 (1.8%) | 126 (57.5%) 21 (9.6%) 25 (11.4%) 16 (7.3%) 14 (6.4%) 4 (1.8%) 8 (3.7%) 5 (2.3%) |

| Time between AAI and notification Within 24 h After 24 h | 116 (70.3%) 49 (29.7%) | 272 (70.1%) 117 (29.9%) | 162 (74.0%) 57 (26.0%) |

| Delay of treatment (n,%) | |||

| No delay (day 0) Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 >Day 7 | 74 (47.1%) 45 (28.7%) 16 (10.2%) 9 (5.7%) 1 (0.6%) 2 (1.3%) 2 (1.3%) 8 (4.8%) | 237 (64.1%) 78 (21.1%) 22 (5.9%) 15 (4.1%) 6 (1.6%) 2 (0.5%) 1 (0.3%) 9 (2.7%) | 74 (39.2%) 37 (19.6%) 31 (16.4%) 20 (10.6%) 7 (3.7%) 9 (4.8%) 5 (2.6%) 6 (3.1%) |

| . | Received PrEP . | Did not receive PrEP . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | RV (N = 165) . | RV (N = 389) . | RIG (N = 219) . |

| General sample characteristics | |||

| Age in (years) (mean, SD) | 27.0 (6.5) | 29.5 (13.2) | 30.5 (13.8) |

| Gender Male (n,%) Female (n, %) | 63 (38.2%) 102 (61.8%) | 178 (45.8%) 211 (54.2%) | 112 (51.1%) 107 (48.9%) |

| Travel duration in (days) (median, IQR) | 58.0 (89.0) | 23.0 (22.5) | 24.0 (24.0) |

| Travel in multiple countries Yes (n,%) No (n,%) | 63 (71.6%) 25 (28.4%) | 72 (40.4%) 106 (59.6%) | 43 (43.4%) 56 (56.6%) |

| Purpose of travel Holiday (n,%) Tour (n,%) Business (n,%) Study/internship (n,%) VFR (n,%) Resident (n,%) Volunteer work (n,%) Other (n,%) | 103 (62.8%) 46 (30.0%) 1 (0.6%) 8 (4.9%) 0 4 (2.4%) 2 (1.2%) 0 | 275 (71.4%) 78 (20.3%) 3 (0.8%) 14 (3.6%) 6 (1.6%) 0 6 (1.6%) 3 (0.8%) | 150 (69.4%) 46 (21.3%) 4 (1.9%) 5 (2.3%) 3 (1.4%) 1 (0.5%) 6 (2.8%) 1 (0.5%) |

| AAI notification (n,%) | |||

| AAI after departure Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 >1 month & ≤ 2 months > 2 months & ≤ 3 months > 3 months | 30 (18.2%) 32 (19.4%) 16 (9.7%) 13 (7.9%) 33 (20.0%) 15 (9.1%) 26 (15.8%) | 126 (32.4%) 97 (24.9%) 56 (14.4%) 30 (7.7%) 33 (8.5%) 17 (4.4%) 30 (7.7%) | 61 (27.9%) 54 (24.7%) 36 (16.4%) 17 (7.8%) 19 (8.7%) 11 (5.0%) 21 (9.6%) |

| Country of AAI (top 5) |

|

|

|

| AAI according to WHO regions South East Asia Western Pacific Europe South America East Mediterranean Africa Central America North America | 80 (48.5%) 40 (24.2%) 4 (2.4%) 21 (12.7%) 3 (1.8%) 12 (7.3%) 3 (1.8%) 2 (1.2%) | 237 (60.9%) 43 (11.1%) 32 (8.2%) 20 (5.1%) 22 (5.7%) 15 (3.9%) 13 (3.3%) 7 (1.8%) | 126 (57.5%) 21 (9.6%) 25 (11.4%) 16 (7.3%) 14 (6.4%) 4 (1.8%) 8 (3.7%) 5 (2.3%) |

| Time between AAI and notification Within 24 h After 24 h | 116 (70.3%) 49 (29.7%) | 272 (70.1%) 117 (29.9%) | 162 (74.0%) 57 (26.0%) |

| Delay of treatment (n,%) | |||

| No delay (day 0) Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 >Day 7 | 74 (47.1%) 45 (28.7%) 16 (10.2%) 9 (5.7%) 1 (0.6%) 2 (1.3%) 2 (1.3%) 8 (4.8%) | 237 (64.1%) 78 (21.1%) 22 (5.9%) 15 (4.1%) 6 (1.6%) 2 (0.5%) 1 (0.3%) 9 (2.7%) | 74 (39.2%) 37 (19.6%) 31 (16.4%) 20 (10.6%) 7 (3.7%) 9 (4.8%) 5 (2.6%) 6 (3.1%) |

Abbreviations: PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; SD, standard deviation; IQR, inter-quartile range; VFR, visiting friends or relatives; AAI, animal-associated injury; ID, Indonesia; TH, Thailand; LK, Sri Lanka; VN, Vietnam; KH, Cambodia; MY, Malaysia; TR, Turkey; CO, Colombia; WHO, World Health Organization; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; RV, rabies vaccinations; RIG, rabies immune globulins; ECA, Eurocross Assistance.

Delay in post-exposure prophylaxis

PEP delay was mainly caused by the delay of the first RV administration intended to be given on day 0, which did not further affect the administration of the subsequent vaccinations. Delay was therefore defined as delay of the first given RV. Travellers who received PrEP pre-travel showed a higher probability of PEP delay, when compared to travellers who did not receive PrEP pre-travel (HR:1.11; 95%CI:1.01–1.22) (Figure 1). Travellers requiring both RV and RIG were more likely to experience PEP delay, compared to the group only needing RV (HR:0.81; 95%CI:0.67–0.96) (Figure 2).

Kaplan–Meier curve for receiving the PEP in days after an AAI according to requirement for RIG. The travellers who required RV & RIG received their PEP 1.23 (1/0.81) times in days later, compared to those who needed only RV. Abbreviations: PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; RV, rabies vaccinations; RIG, rabies immune globulins

Kaplan–Meier curve for delay in RIG treatment in days after an AAI, according to WHO region where the AAI occurred (N = 189). Abbreviations: RIG, rabies immune globulins; WHO, World Health Organization; AAI, animal-associated injury

Risk factors associated with delay in PEP

Because of the significant association between PEP delay and pre-travel PrEP on the one hand, and between PEP delay and the need of RIG on the other hand, analyses were performed after stratification between PrEP and unvaccinated PrEP, and the need of RIG or not (Supplemental Table 2).

Age, gender, travel duration, purpose of travel and travelling in multiple countries were not associated with PEP delay. However, for most WHO regions, we found a delay in RIG administrations after an AAI (Supplemental Table 2). We found the median delay in Central America to be more than 5 days, almost 4 days in South America and almost 3 days in East Mediterranean. The HR for receiving RIG within 24 h was the lowest in Central America (HR:0.31; 95%CI:0.13–0.70), followed by South America (HR:0.34; 95%CI:0.19–0.61), East Mediterranean (HR:0.46; 95%CI:0.24–0.89) and Europe (HR:0.48; 95%CI:0.19–0.81), compared with the reference category South East Asia (Supplemental Table 2/Figure 3).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that rabies PEP treatment was delayed in up to 60% among a sample of Dutch travellers who contacted their medical assistance agency because of an AAI while being abroad; PEP delay occurred mostly in travellers requiring RIG and in those who travelled to Central America, South America and Eastern Mediterranean.

Travellers who received PrEP travelled for a longer period of time and visited more countries during their stay abroad.2,6,18,20 This is in line with the current guidelines. The Dutch National Coordination Centre for Travellers’ Health Advice (LCR) recommends pre-travel PrEP to travellers who stay abroad for over three months, based on the well-known cumulative risk on encountering an AAI during a longer stay in rabies-endemic countries.10,11,13 As previously reported, we found that most AAIs occurred within the first month after departure.8–10,24 This might be attributable to the fact that most travellers go abroad for less than one month.

The most important factor that was associated with PEP delay was the WHO region in which the AAI occurred. Especially when RIG was indicated, delay was most pronounced for subjects travelling in Central America, South America and Eastern Mediterranean. RIG in particular is known to be scarce or even unavailable in some countries that carry the highest burden of canine rabies.4,24,26 Gautret et al. described that almost two-third of international travellers who encountered an AAI did not receive RIG in the country of exposure.20 Jentes et al. analysed the geographic availability of PEP/RIG, based on information provided by the local health care centres themselves.24 They concluded that RIG was often inaccessible in Tropical South America, Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. In other regions (Middle East, North Africa, Australia and South/Western Pacific) RIG was almost always available (>94%). Contrary to RIG, the RV was almost always accessible regardless to region (91%).24 In line with Jentes et al. our results showed that Central America, South America, East Mediterranean and Eastern Europe were WHO regions with the highest risk of increased RIG treatment delay.24 In our study it took travellers on average more than 3 days in Central America, South America and East Mediterranean to obtain RIG after an AAI. Despite the fact that rabies endemicity largely varies across countries, in case of an AAI, PEP delay should be avoided to minimize health risks. PEP delay might not only lead to an increased infection risk, but it might also have an important impact on the individual well-being, in terms of anxiety and emotional distress.

Possible factors that might explain PEP delay are inaccessibility to PEP, logistical issues, late notification by the patient, patient refusal advice and discrepancy in treatment advice between local health care provider and ECA physician, which was mentioned more than once in the received notifications. However, these factors were not investigated in this study.

Our findings that most AAIs occur within the first month after departure and the significant PEP delay due to unavailability of especially RIG in countries like Central and South America suggest the need of re-evaluation of the current pre-travel guidelines. Although rabies is less endemic in several regions of Central and South America compared to Asia,1 the reported delay suggests that travel destination should be considered as well during the pre-travel advice and decision-making about the need of PrEP. As mentioned before the current Dutch guidelines are largely based on travel duration.2 However, exact exposure risk of travellers is difficult to access based on the large variety of risk factors.12,17,22,23 This might explain the large variation in international opinions on which travellers should receive PrEP. In a recent publication Steffen & Hamer claim the need to prioritize rabies PrEP and clearly highlight a more liberal vision on pre-travel consultations,23 thus underlining the importance of a broader risk evaluation.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, detailed information was obtained directly from the travellers themselves while being abroad, minimizing recall bias.10,24 Second, the obtained information was particularly detailed in terms of the information about PEP delay. Third, to our knowledge the first study thoroughly investigated contributing factors to PEP delay, in a well-known fatal disease. We were able to identify geographical destination as an important risk factor for delay, which may support adaptation of the current guidelines on PrEP rabies vaccination in travellers.

Some limitations also require comments. First, the study population was Dutch travellers who encountered an AAI and actively contacted ECA. No information from other emergency medical assistance centres was used. Therefore, selection bias may be present. Second, data about availability and accessibility of PEP were in some cases incomplete. Additionally, in our study we stated that the PEP should be given at day 0 (<24 h) in order to define ‘no delay’. However, in literature different time intervals for PEP administration are used.1,2 Third, the included groups consisted of travellers who encountered an AAI and having reported it. Possibly we miss the population that autonomously sought medical advice or only after having returned to their home country. In addition, Heitkamp et al. showed in their study that only 19% of travellers after an AAI sought medical care.17

Future studies are needed to objectify a possible increase of AAIs. In addition, the origin of this increase should be investigated to anticipate on this with proper interventions, such as more extensive pre-travel information and advice. Marano et al. showed that the perceived risk of exposure to rabies for travellers was low.22 Furthermore, reasons for the described delay in this research are not fully addressed yet and merit a more close examination in future work, especially since discrepancy between WHO guidelines and local advice was reported, thus suggesting that WHO recommendations are not properly followed. In addition, general sample characteristics in combination with PEP delay might play a key role in future prevention interventions.1,27,32 In order to more closely examine this role, prospective studies are advisable.

Conclusion

Within our sample, an AAI occurs within three months period, more specifically within the first four weeks, and PEP treatment is delayed on a large scale, mainly in specific geographical regions, and particularly when RIG is indicated.9–11 Given the potential health risk of PEP delay, delay should preferably be avoided, or at least reduced. An effective strategy to achieve minimal PEP delay would be to increase awareness of rabies exposure risk among travellers on the one hand and on the other hand to take into consideration the travel destination and the local RIG availability and accessibility, in the decision-making for PrEP necessity during pre-travel advice.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Prof. Jelle J. Goeman for his help in the practical implementation of the data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Leiden University Medical Centre, Eurocross Assistance and the Vrije University (VU) Amsterdam. No sources of funding were used because L.V. did the research in combination with an internship (Final Internship Master of Health Sciences, specialisation Infectious diseases, at the VU Amsterdam).

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Prof. L.G.V. and F.S.L. made the co-operation between the Leiden University Medical Centre and Eurocross Assistance possible. Together with L.V., they designed and put up the study. L.V. did the data collection, wrote the manuscript and performed all statistical analyses with the support of all co-authors, but especially with the support of F.S.L. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was extensively reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (METC Leiden-Den Haag-Delft) as not subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.