-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Vuong Minh Nong, Quyen Le Thi Nguyen, Tra Thu Doan, Thanh Van Do, Tuan Quang Nguyen, Co Xuan Dao, Trang Huyen Thi Nguyen, Cuong Duy Do, The second wave of COVID-19 in a tourist hotspot in Vietnam, Journal of Travel Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 2, March 2021, taaa174, https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa174

Close - Share Icon Share

By 8 September 2020, Vietnam reported a total of 1049 laboratory confirmation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), with 35 deaths. After successfully containing the first wave1 followed by 99 days without any further local cases, the second wave of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) started on 25 July in a major hospital in Da Nang—the biggest tourist city in the country with >1 million local citizens and ~8 million tourists annually. During the period from 25 July to 1 August, new incident cases increased by ~30% after only 1 week, the fastest growing rate since the beginning of the epidemic.

There were a total of 551 cases related to the outbreak in Da Nang, as reported by 8 September, 58.8% female, median age was 46 years, and 26.1% were aged ≥60. About half of all SARS-CoV-2 cases were found in the hospital setting (49.4%), with Da Nang Hospital (DNH) as the epicentre of the outbreak (251 cases, 45.6%). Among cases detected in hospitals, there were 9.9% health care workers (HCWs), 44.9% patients, 34.9% family caregivers and 10.3% persons who had visited the hospital. There were 279 cases detected in the community, 175 were investigated as close contacts of positive cases (62.7%) and 104 cases did not identify the source of transmission (Supplementary Table S1). A total of 15 major cities/provinces reported cases linked to the Da Nang outbreak, with most of cases detected in Da Nang (71.0%), followed by Quang Nam (16.9%), Hai Duong (2.9%), Hanoi (1.8%) and Ho Chi Minh City (1.5%). Our observations emphasize the potential threat of unrecognized rapid community spread even in successful outbreak-controlled countries such as Vietnam or New Zealand, and the importance of prevention of nosocomial infections in hospitals. Rigorous infection prevention control measures should be continued in medical settings until a vaccine is rolled out.

Responses of Vietnam to the Second Wave of COVID-19

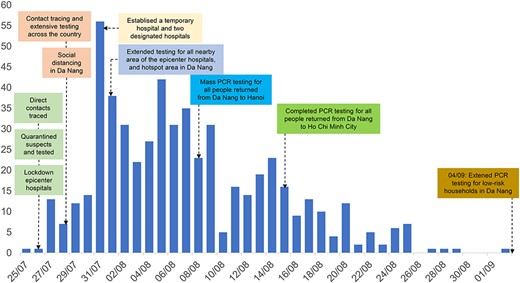

In Vietnam, a large nosocomial outbreak previously occurred in March at the biggest hospital in the North—Bach Mai Hospital (BMH). The successful experience from the BMH outbreak was a valuable lesson of how to prevent further community transmission from a nosocomial outbreak through mass testing of all suspected cases, lockdown, vigorous contact tracing, quarantine all the possibly contacts and social distancing.2 In Da Nang, 1 day after the first case was detected, three hospitals in a medical complex area with the centre was DNH were put under lockdown. A total of 6018 persons were considered as suspected cases and put in quarantine, including HCWs, non-clinical staff, patients and family caregivers. An addition of 6665 persons traced as direct contacts of positive cases were also quarantined and tested, as reported on 30 July. The laboratory capacity for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of SARS-CoV-2 in Da Nang was increased to ~10 000 samples per day supported by BMH and the Ho Chi Minh City Pasteur Institute. In early August, mass testing was expanded to nearby residential areas of the hospital complex and other high-risk areas in the community. From 25 July to 2 September, an estimated 228 000 people were tested in Da Nang (~25% of the total population). On 3 September, the city planned to extend the testing for 71 424 low-risk households, one sample for each household. Social distancing was applied on 28 July for the whole city when all non-local citizen returned to their home province (Figure 1). Hundreds of experienced HCWs from Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City were sent to Da Nang to support the control efforts, similarly to what China did for Wuhan.3 A temporary hospital for care and treatment for suspected cases and mild cases of COVID-19 was built, following the concept of Fangcang hospitals in China,4 in addition to two designated hospitals that were rapidly established and put under the directly direction of a special committee from the Ministry of Health.

Timeline of COVID-19 outbreak at Da Nang from 25 July to 8 September 2020.

The second wave occurred after >3 months of no detection of local cases in Vietnam, when the intra-country prevention measures had been eased, including the lifting of national social distancing in April, reopening of entertainment activities and stimulation of domestic tourism. From 1 July to 27 July, it was estimated that >1.5 million people returned from Da Nang to other provinces of Vietnam, of which ~41 000 people had visited DNH. The containment strategy varied between provinces, depending on the local laboratory capacity and ability to do contact tracing. Community measures similar to those in rural areas of China5 were employed for rural areas in Vietnam. Hanoi is the capital city with the largest number of contacts, hence mass testing was done for ~100 000 persons using the rapid antibody test, with strict quarantine and mobility restrictions. The control approach in Hanoi was almost similar to the contain strategy in South Korea.6 However, several studies indicated that the rapid tests had low sensitivity at early stage or for those with asymptomatic infections.7,8 False negative result might create a sense of false reassurance among both suspected cases and HCWs. This strategy quickly revealed its limitations when two cases that had negative test result based on the rapid test were soon found to be positive by RT-PCR, which resulted in mass retesting for all the contacts and suspect cases with the RT-PCR methods in Hanoi.

Other provinces with lower number of tracing contacts carried out less aggressive approach, but still followed the general principle of vigorous tracing, isolating and testing if symptomatic. For example, Ho Chi Minh City, the biggest metropolitan city in South Vietnam, received ~52 449 people returning from Da Nang. Consequently, Ho Chi Minh City conducted contacts tracing of all persons from Da Nang and stratified them into three groups. People with respiratory symptoms or those exposed to the three epicentre hospitals in Da Nang were placed in centralized quarantined and tested for SARS-CoV-2; other cases were isolated and monitored at home by local commune health staff.

In addition, a mobile application, named ‘Blue-zone’, was developed and made freely available to all residents in Vietnam. By 20 August, the application had exceeded 20 million downloads.

Current Challenges and Future Directions

One of the biggest challenges of the outbreak in Da Nang was the high disease burden in the elderly with comorbidities as a consequence of the widespread of nosocomial transmission among patients at DNH. The proportion of severe or critical cases was >10%, which was significantly higher than during the first wave where only five cases (1.2%) required ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. There were 35 deaths, mostly among patients aged ≥60 years and those with serious underlying medical problems such as end-stage kidney diseases, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases or cancer, in line with published data from the UK.9

The second challenge was the asynchronous capacity across provinces for quarantine, contact tracing and testing. Recent studies indicate a moderate level of local capacity to deal with the epidemic response, especially in rural areas and southern region.10 Mobilization of resources to localities with poor health system was critical for contact tracing and managing of >1.5 million people linked to the Da Nang outbreak.

Authors’ Contribution

N.M.V. and D.D.C. conceived the manuscript and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.