-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Catherine McNestry, Anna Hobbins, Niamh Donnellan, Paddy Gillespie, Fionnuala M McAuliffe, Sharleen L O’Reilly, Latch On Consortium , Evaluation of a complex intervention: the Latch On randomized controlled trial of multicomponent breastfeeding support for women with a raised body mass index, Journal of Public Health, Volume 47, Issue 1, March 2025, Pages e116–e126, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdae282

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Latch On’s objective was to achieve improved breastfeeding rates in women with raised body mass indices using a multicomponent breastfeeding support intervention.

A hybrid type 1 implementation-effectiveness trial with mixed-methods process and health economics analyses were conducted. Data collection included stakeholder questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, fidelity data, participant and health system costs.

The intervention was delivered with fidelity but the high breastfeeding rates at 3 months were not different between intervention and usual care. Participants receiving the minimum intervention dose were more likely to initiate breastfeeding (P = 0.045) and be breastfeeding at hospital discharge (P = 0.01) compared with participants below the threshold. Participant exit interview themes highlighted the importance of improving breastfeeding support to women, the effect of COVID-19 on the breastfeeding experience, and found that the intervention improved the experience of establishing breastfeeding. The intervention cost €157 per participant, with no other cost difference between groups. Process analysis found that follow-up breastfeeding services continued in half of sites after study completion.

This low-cost intervention resulted in a more enjoyable breastfeeding experience for participants and changed practice in some study sites. The intervention dose received may impact effectiveness, but further research is needed to provide definitive evidence of clinical and cost effectiveness.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends breastfeeding as the sole source of nutrition for infants under 6 months, and continued complementary breastfeeding up to and beyond the first 2 years.1 Breastfeeding confers numerous public health benefits, including reduced infant and child morbidity and mortality, optimal pregnancy spacing and long-term health benefits for both women and infants.2,3 Ireland has one of the lowest breastfeeding rates worldwide at all timepoints, a legacy of formula marketing and perpetuated by the resulting loss of breastfeeding culture.4,5 Reduced breastfeeding rates are evident with gross domestic product increases in low- and middle-income countries, and rates tend to be lowest in high-income countries.6 Overweight and obesity rates in reproductive age women are increasing worldwide, and the Irish population is no stranger to this phenomenon with 50% overweight/obesity rates in pregnancy.7,8

In total, 80–92% of Irish women expecting their first child intend to breastfeed.9,10 Of those who succeed, up to two-thirds stop before they want to due to obstacles encountered and a lack of healthcare provider support.11 Women with overweight or obesity have additional challenges establishing breastfeeding and are at risk of reduced breastfeeding success.12 The Latch On randomized controlled trial (RCT) was a prospectively registered multicomponent breastfeeding support intervention for women with overweight and obesity.13 This was a type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation study, designed to test the intervention effects whilst observing and gathering information on implementation.13–15 Whilst we did not prove the primary hypothesis, we found that access to breastfeeding support—public or private—may have resulted in high breastfeeding rates across the entire study population.15 Here, we aim to explore the factors impacting the process and health economic analysis of a breastfeeding support intervention embedded in maternity services.

Methods

Study design

This manuscript used the recommendations of the standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRi) statement checklist (Supplementary File 1). The Latch On RCT commenced in June 2019 and took place in four maternity centres in Ireland; it continued through the COVID-19 pandemic to June 2022. Two hundred and twenty five women were recruited and randomized. The National Maternity Hospital (NMH), Dublin, is one of the busiest maternity hospitals in Europe with c.8000 births annually. Wexford General Hospital (WGH), Wexford, St. Luke’s’ Hospital (SLH), Kilkenny and Midlands Regional Hospital (MRH), Mullingar, are smaller, regional hospitals, each with a maternity centre serving a rural population. Approximately 2000 babies delivered are delivered annually in WGH each year, c.1600 in SLH and c.1900 in MRH.

Breastfeeding rates at 3 months in the hospitals’ catchment areas ranged from 32.4–45.7% at study initiation.13 Full details of the trial protocol and primary outcome are available,13,15,16 and further details are provided in the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (see Supplementary File 2).

The Latch On multicomponent intervention comprised of a tailored participant and support partner breastfeeding education class, a postnatal inpatient face-to-face breastfeeding assessment and weekly postnatal telephone support for up to 6 weeks. The intervention was delivered by an International Board-Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC). Drop-in breastfeeding clinic was available for intervention participants in NMH and WGH, by-appointment follow-up in SLH and online group support in MRH. Usual care included optional general antenatal classes and face-to-face lactation support if breastfeeding problems were encountered. Drop-in breastfeeding clinic was available as part of usual care in NMH, and by-appointment in SLH. The covid-19 pandemic occurred during the trial and necessitated some changes to the intervention, such as moving the education class online.13,15

Inclusivity

The study design did not include collection of participant gender identity. Although ‘breastfeeding’, ‘woman’ and other gendered terms may not be the preferred terminology for all persons who give birth and/or feed their offspring with their own milk, we have used them in this manuscript for brevity and because they are widely understood.

Data collection

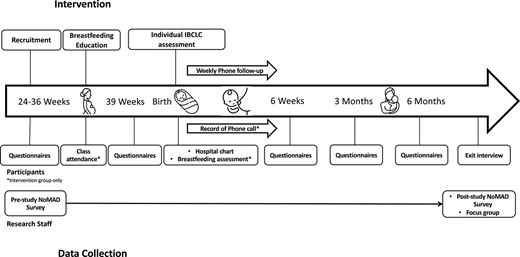

The quant-qual mixed methods consisted of semi-structured qualitative staff focus group (n = 5 IBCLC, n = 1 midwifery manager) and participant exit interviews (n = 28, n = 1 support partner) undertaken at study completion using purposive sampling of all study staff and participants. All participants who completed the study were invited to interview. Exit interviews were scheduled with interested respondents, ensuring a balance of intervention and usual care groups. All midwifery and IBCLC staff from each centre were invited to attend the focus group. Representation from all study centres was ensured in both the exit interviews and focus group. The focus group and interviews were digitally recorded using Zoom (V.5.13.11) with verbal consent to record. The interview scripts are available in Supplementary File 3. All transcripts were checked and anonymized prior to recording deletion. ND and CMcN facilitated the interviews and focus groups respectively. Normalization process theory (NPT)17,18 was applied to the focus group schedule and analysis to explore the extent to which the staff normalized it within their usual practice. The quantitative methods involved participant questionnaires,15 intervention delivery process records and staff NOrmalization MeAsure Development (NoMAD) survey at study beginning and end. The NoMAD survey is a validated 23-item questionnaire for measuring complex intervention implementation processes from the staff perspective, with each item scored 0–5.19 The cost of implementing Latch On in clinical practice was estimated prospectively alongside the RCT by the study research team, including resources relating to the IBCLC’s time input and general administration costs. Other healthcare resource use was captured via participant cost diaries at 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months postpartum. Health outcome data was collected via participant responses to a modified version of the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding, the Breastfeeding Experience Scale and the EuroQol EQ-5D-5L instrument at the same timepoints.20–22 Fig. 1 illustrates the data collection timepoints through the course of the study.

Data analysis

The participant interviews and staff focus group were independently analyzed (CMcN, ND) using reflexive thematic analysis.23 Both researchers have academic and professional experience in breastfeeding, CMcN has lived breastfeeding experience, and both have normal body mass indices (BMI). Reflective discussions between researchers involved guidance from a third senior researcher (SOR, dietitian, lived breastfeeding experience, normal BMI). The National Institute of Health Behaviour Change Consortium recommendations were used to assess the five domains of study fidelity using intervention delivery process records and quantitative data collected.24 CMcN (team member independent of study design and intervention delivery) completed the fidelity analysis. NoMAD survey data were grouped into NPT constructs for analysis25 and Wilcoxon’s signed rank test used to compare constructs between timepoints. Breastfeeding outcomes for participants who received minimum or higher intervention dose versus suboptimal dose were compared using Chi-square. SPSS (Mac V27) was used for analysis.

The economic evaluation followed the Health Information and Quality Authority of Ireland guidelines.26 The perspective of the healthcare provider was adopted. The economic analysis was conducted on an intention to treat basis. Resource use was costed using 2020 Euro unit cost prices. Summary data for resource usage and costs for each resource category at each timepoint were presented. Health outcomes were expressed in terms of quality adjusted life years (QALYs) at 6 months calculated using the EuroQol EQ-5D-5L.22,27,28 EQ-5D-5L responses were transformed using an algorithm into a single health state index score, based on values elicited via the time trade-off and discrete choice approach for the Irish population.29 EQ-5D-5L index scores were used to calculate participant-specific QALYs gained at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months respectively using the area under the curve method.30 Independent t-tests were conducted to compare health outcome estimates. Given the length of follow-up, neither costs nor outcomes were discounted. The cost effectiveness analyses at each timepoint were estimated. Analysis was undertaken using Stata (V.17.0). Ethical approval was received from the NMH Ethics Committee (ref EC.24.2018), Midlands Areas Research Ethics Committee (ref 130219FMcA), and Southeast Research Ethics Committee (ref: 19.01). All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Fidelity

Study design and training

The intervention was designed using the COM-B behaviour change model15,31 and the Medical Research Council complex intervention framework32 and is fully detailed within the protocol paper.13 Training was delivered at each site for the IBCLCs in early 2019. The same researcher delivered all training. Standardized training resources detailing the breastfeeding class content, research handbook, study folder, posters and information leaflets were provided. The training took a minimum of 3 hours and included site-specific implementation plans and addressing any potential local barriers. Postnatal lactation assessment and support fall within the existing scope of practice of IBCLCs so this was not included.

Intervention delivery

All participant encounters were recorded, and electronic prompts used to remind the team to contact participants at designated timepoints. Feedback was recorded via study evaluation forms at each postnatal timepoint. Providers filled a checklist of intervention components delivered following each contact, as well as optional free text records. Providers also interacted with control participants as part of usual care. Participant comprehension was assessed via discussion of material during the group breastfeeding class, and individual skills assessment and monitoring by the IBCLC at each postnatal contact. Individual assessments and follow-up content and duration were tailored to participant requirements.

Receipt of intervention

In total, 94.6% (n = 96) participants received the Latch On breastfeeding class. Site delivery varied from 90.9% to 100%. A total of 88.7% (n = 90) participants received the in-person lactation assessment. Two were excluded due to dropping out or preterm delivery respectively, three chose to formula feed from birth and the remainder were due to early transfer home, weekend delivery, or lactation staff annual leave. Site delivery ranged from 75.0% to 90.9%.

In total, 87.7% (n = 89) participants received telephone follow up with 41.5% (n = 39) receiving 1–3 phone calls, 29.3% (n = 30) 4–5 phone calls and 17.0% (n = 17) 6 or more calls. In total, 76.4% (n = 80) participants attended a drop-in breastfeeding clinic. Phone support delivery was >78% in all centres, apart from one (25%). Here, a weekly online support group was provided as an alternative, but records were not kept of these sessions. One usual care participant received the full postnatal intervention, due to human error.

The minimum dose was defined as receipt of the Latch On breastfeeding class, postnatal individual lactation assessment and any phone follow-up. A total of 75.5% (n = 77) received at least the minimum dose with 16.7% (n = 17) of those receiving the full intervention; 24.9% (n = 25) received a suboptimal dose.

Within the intervention group, breastfeeding initiation and any breastfeeding at hospital discharge differed between those who received the minimum dose and those who received a suboptimal dose (initiation 76/77 [98.7%] vs. 22/25 [88.0%] P = 0.045); any breastfeeding at hospital discharge (73/77 [98.6%] vs. 21/25 [84.0%] P = 0.01). This dose relationship was not maintained beyond this timepoint, and exclusive breastfeeding rates did not differ.

Process evaluation

Intervention normalization

NoMAD surveys were completed by intervention delivery staff pre- (n = 7) and post-intervention (n = 5). Intervention familiarity increased over time (Z = −2.03, P = 0.04), but identifying the intervention as part (Z = −1.473 P = 0.14) or becoming part of normal work did not (Z = −1.58 P = 0.13). NPT analysis of the focus group found that intervention normalization resulted in continuation of follow-up breastfeeding services in two study centres where it was previously not available. A summary of intervention normalization by staff is provided in Table 1.

| Construct . | Pre-study . | Post-study . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Outcomes . | Quotes . |

| Coherence | |||

| Understanding of and investment in the Latch On intervention | The intervention as a whole was not clearly differentiated from normal work for all staff | ‘we previously would have had antenatal classes for the women, but that, there were specific ones for the intervention group, but was there any real difference Staff Member 2?’ (Staff Member 1) ‘No’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Intervention components were understood as separate to usual care | ‘So all the added extras of following them up weren’t part of the usual routine’(Staff Member 2) ‘it wasn’t normal practice that everybody got to see an IBCLC post-delivery.’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Staff investment evident | ‘you can also feel that you are the one that’s passionate about it, and that you will push it because you are the one’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 6 Post-study n = 5 | 15.0 (3.58) | 15.2 (1.92) | P = 0.892a |

| Cognitive Participation | |||

| Engagement of individual staff members and groups with the Latch On intervention | Motivation to participate was affected by research staff team turnover, the COVID-19 pandemic and extended study duration | ‘we kept trying to plod on, but the wasn’t the passion, you didn’t feel the drive as much’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| Wider staff body engagement was more evident in smaller units | ‘we got a system going where the girls would maybe highlight mums that might have been or antenatal ladies that might have been suitable.’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| Staff expressed doubt as to whether the intervention was worthwhile compared to usual care, as perception of midwife provided support was very positive | ‘you have to ask the question does every woman need to be seen by an IBCLC person qualified, rather than a midwife, who is, part of her role is lactation.’ (Staff Member 5) ‘in hospital consults to women, you know, the resources are better used, the IBCLCs are actually seeing people that are referred by the midwives on the ward…they were very well looked after by the midwives’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 7 Post-study n = 5 | 19.1 (1.46) | 17.4 (2.61) | P = 0.14a |

| Collective action | |||

| Interaction of the intervention with existing ways of working | Systems developed to integrate the intervention into existing work practices in some units | ‘everybody had a sticker that was in the intervention and they were flagged, and so they knew then to contact me who was running the study’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| IBCLCs were very comfortable delivering the intervention but this was tempered by feelings of isolation and overwork | ‘the delivery part and the follow up part was very much part of the role, so it was very familiar and very comfortable’ (Staff Member 3) ‘it definitely was extra add to the workload’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| Management support was evident, although did not always result in support with workload | ‘the whole project was…an ownership piece from a lactation perspective from my point of view, so, certainly not not supported but it would have just been seen as our work piece’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| NoMAD Score (7–35) Pre-study n = 3 Post-study n = 5 | 32.3 (2.52) | 28.2 (3.19) | P = 0.66a |

| Reflexive monitoring | |||

| How the Latch On intervention is understood and appraised by stakeholders | IBCLCs had mixed opinions about the intervention but agreed engaged participants benefitted | ‘I think the people that were the right fit for the actual intervention group and the ones that were motivated to come back would have got a lot out of it’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Study feedback was not given to staff but they were aware of participant engagement with the intervention | ‘all in all, I suppose, got on well, but I don’t know how it shows on paper’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Practice change continues in some centres with increased drop-in breastfeeding clinics | ‘that was the first thing that they wanted us to do, was get that six week clinic up, so we have that running since February’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD Score (5–25) Pre-study n = 2 Post-study n = 5 | 24.0 (0.0) | 21.0 (1.73) | -* |

| Construct . | Pre-study . | Post-study . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Outcomes . | Quotes . |

| Coherence | |||

| Understanding of and investment in the Latch On intervention | The intervention as a whole was not clearly differentiated from normal work for all staff | ‘we previously would have had antenatal classes for the women, but that, there were specific ones for the intervention group, but was there any real difference Staff Member 2?’ (Staff Member 1) ‘No’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Intervention components were understood as separate to usual care | ‘So all the added extras of following them up weren’t part of the usual routine’(Staff Member 2) ‘it wasn’t normal practice that everybody got to see an IBCLC post-delivery.’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Staff investment evident | ‘you can also feel that you are the one that’s passionate about it, and that you will push it because you are the one’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 6 Post-study n = 5 | 15.0 (3.58) | 15.2 (1.92) | P = 0.892a |

| Cognitive Participation | |||

| Engagement of individual staff members and groups with the Latch On intervention | Motivation to participate was affected by research staff team turnover, the COVID-19 pandemic and extended study duration | ‘we kept trying to plod on, but the wasn’t the passion, you didn’t feel the drive as much’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| Wider staff body engagement was more evident in smaller units | ‘we got a system going where the girls would maybe highlight mums that might have been or antenatal ladies that might have been suitable.’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| Staff expressed doubt as to whether the intervention was worthwhile compared to usual care, as perception of midwife provided support was very positive | ‘you have to ask the question does every woman need to be seen by an IBCLC person qualified, rather than a midwife, who is, part of her role is lactation.’ (Staff Member 5) ‘in hospital consults to women, you know, the resources are better used, the IBCLCs are actually seeing people that are referred by the midwives on the ward…they were very well looked after by the midwives’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 7 Post-study n = 5 | 19.1 (1.46) | 17.4 (2.61) | P = 0.14a |

| Collective action | |||

| Interaction of the intervention with existing ways of working | Systems developed to integrate the intervention into existing work practices in some units | ‘everybody had a sticker that was in the intervention and they were flagged, and so they knew then to contact me who was running the study’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| IBCLCs were very comfortable delivering the intervention but this was tempered by feelings of isolation and overwork | ‘the delivery part and the follow up part was very much part of the role, so it was very familiar and very comfortable’ (Staff Member 3) ‘it definitely was extra add to the workload’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| Management support was evident, although did not always result in support with workload | ‘the whole project was…an ownership piece from a lactation perspective from my point of view, so, certainly not not supported but it would have just been seen as our work piece’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| NoMAD Score (7–35) Pre-study n = 3 Post-study n = 5 | 32.3 (2.52) | 28.2 (3.19) | P = 0.66a |

| Reflexive monitoring | |||

| How the Latch On intervention is understood and appraised by stakeholders | IBCLCs had mixed opinions about the intervention but agreed engaged participants benefitted | ‘I think the people that were the right fit for the actual intervention group and the ones that were motivated to come back would have got a lot out of it’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Study feedback was not given to staff but they were aware of participant engagement with the intervention | ‘all in all, I suppose, got on well, but I don’t know how it shows on paper’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Practice change continues in some centres with increased drop-in breastfeeding clinics | ‘that was the first thing that they wanted us to do, was get that six week clinic up, so we have that running since February’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD Score (5–25) Pre-study n = 2 Post-study n = 5 | 24.0 (0.0) | 21.0 (1.73) | -* |

Note: numerical data presented as mean (SD).

aWilcoxon signed-rank test used to compare groups.

*Not possible to test due to missing data.

| Construct . | Pre-study . | Post-study . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Outcomes . | Quotes . |

| Coherence | |||

| Understanding of and investment in the Latch On intervention | The intervention as a whole was not clearly differentiated from normal work for all staff | ‘we previously would have had antenatal classes for the women, but that, there were specific ones for the intervention group, but was there any real difference Staff Member 2?’ (Staff Member 1) ‘No’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Intervention components were understood as separate to usual care | ‘So all the added extras of following them up weren’t part of the usual routine’(Staff Member 2) ‘it wasn’t normal practice that everybody got to see an IBCLC post-delivery.’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Staff investment evident | ‘you can also feel that you are the one that’s passionate about it, and that you will push it because you are the one’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 6 Post-study n = 5 | 15.0 (3.58) | 15.2 (1.92) | P = 0.892a |

| Cognitive Participation | |||

| Engagement of individual staff members and groups with the Latch On intervention | Motivation to participate was affected by research staff team turnover, the COVID-19 pandemic and extended study duration | ‘we kept trying to plod on, but the wasn’t the passion, you didn’t feel the drive as much’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| Wider staff body engagement was more evident in smaller units | ‘we got a system going where the girls would maybe highlight mums that might have been or antenatal ladies that might have been suitable.’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| Staff expressed doubt as to whether the intervention was worthwhile compared to usual care, as perception of midwife provided support was very positive | ‘you have to ask the question does every woman need to be seen by an IBCLC person qualified, rather than a midwife, who is, part of her role is lactation.’ (Staff Member 5) ‘in hospital consults to women, you know, the resources are better used, the IBCLCs are actually seeing people that are referred by the midwives on the ward…they were very well looked after by the midwives’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 7 Post-study n = 5 | 19.1 (1.46) | 17.4 (2.61) | P = 0.14a |

| Collective action | |||

| Interaction of the intervention with existing ways of working | Systems developed to integrate the intervention into existing work practices in some units | ‘everybody had a sticker that was in the intervention and they were flagged, and so they knew then to contact me who was running the study’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| IBCLCs were very comfortable delivering the intervention but this was tempered by feelings of isolation and overwork | ‘the delivery part and the follow up part was very much part of the role, so it was very familiar and very comfortable’ (Staff Member 3) ‘it definitely was extra add to the workload’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| Management support was evident, although did not always result in support with workload | ‘the whole project was…an ownership piece from a lactation perspective from my point of view, so, certainly not not supported but it would have just been seen as our work piece’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| NoMAD Score (7–35) Pre-study n = 3 Post-study n = 5 | 32.3 (2.52) | 28.2 (3.19) | P = 0.66a |

| Reflexive monitoring | |||

| How the Latch On intervention is understood and appraised by stakeholders | IBCLCs had mixed opinions about the intervention but agreed engaged participants benefitted | ‘I think the people that were the right fit for the actual intervention group and the ones that were motivated to come back would have got a lot out of it’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Study feedback was not given to staff but they were aware of participant engagement with the intervention | ‘all in all, I suppose, got on well, but I don’t know how it shows on paper’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Practice change continues in some centres with increased drop-in breastfeeding clinics | ‘that was the first thing that they wanted us to do, was get that six week clinic up, so we have that running since February’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD Score (5–25) Pre-study n = 2 Post-study n = 5 | 24.0 (0.0) | 21.0 (1.73) | -* |

| Construct . | Pre-study . | Post-study . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Outcomes . | Quotes . |

| Coherence | |||

| Understanding of and investment in the Latch On intervention | The intervention as a whole was not clearly differentiated from normal work for all staff | ‘we previously would have had antenatal classes for the women, but that, there were specific ones for the intervention group, but was there any real difference Staff Member 2?’ (Staff Member 1) ‘No’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Intervention components were understood as separate to usual care | ‘So all the added extras of following them up weren’t part of the usual routine’(Staff Member 2) ‘it wasn’t normal practice that everybody got to see an IBCLC post-delivery.’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Staff investment evident | ‘you can also feel that you are the one that’s passionate about it, and that you will push it because you are the one’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 6 Post-study n = 5 | 15.0 (3.58) | 15.2 (1.92) | P = 0.892a |

| Cognitive Participation | |||

| Engagement of individual staff members and groups with the Latch On intervention | Motivation to participate was affected by research staff team turnover, the COVID-19 pandemic and extended study duration | ‘we kept trying to plod on, but the wasn’t the passion, you didn’t feel the drive as much’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| Wider staff body engagement was more evident in smaller units | ‘we got a system going where the girls would maybe highlight mums that might have been or antenatal ladies that might have been suitable.’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| Staff expressed doubt as to whether the intervention was worthwhile compared to usual care, as perception of midwife provided support was very positive | ‘you have to ask the question does every woman need to be seen by an IBCLC person qualified, rather than a midwife, who is, part of her role is lactation.’ (Staff Member 5) ‘in hospital consults to women, you know, the resources are better used, the IBCLCs are actually seeing people that are referred by the midwives on the ward…they were very well looked after by the midwives’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| NoMAD score (4–20) Pre-study n = 7 Post-study n = 5 | 19.1 (1.46) | 17.4 (2.61) | P = 0.14a |

| Collective action | |||

| Interaction of the intervention with existing ways of working | Systems developed to integrate the intervention into existing work practices in some units | ‘everybody had a sticker that was in the intervention and they were flagged, and so they knew then to contact me who was running the study’ (Staff Member 4) | |

| IBCLCs were very comfortable delivering the intervention but this was tempered by feelings of isolation and overwork | ‘the delivery part and the follow up part was very much part of the role, so it was very familiar and very comfortable’ (Staff Member 3) ‘it definitely was extra add to the workload’ (Staff Member 2) | ||

| Management support was evident, although did not always result in support with workload | ‘the whole project was…an ownership piece from a lactation perspective from my point of view, so, certainly not not supported but it would have just been seen as our work piece’ (Staff Member 3) | ||

| NoMAD Score (7–35) Pre-study n = 3 Post-study n = 5 | 32.3 (2.52) | 28.2 (3.19) | P = 0.66a |

| Reflexive monitoring | |||

| How the Latch On intervention is understood and appraised by stakeholders | IBCLCs had mixed opinions about the intervention but agreed engaged participants benefitted | ‘I think the people that were the right fit for the actual intervention group and the ones that were motivated to come back would have got a lot out of it’ (Staff Member 2) | |

| Study feedback was not given to staff but they were aware of participant engagement with the intervention | ‘all in all, I suppose, got on well, but I don’t know how it shows on paper’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| Practice change continues in some centres with increased drop-in breastfeeding clinics | ‘that was the first thing that they wanted us to do, was get that six week clinic up, so we have that running since February’ (Staff Member 4) | ||

| NoMAD Score (5–25) Pre-study n = 2 Post-study n = 5 | 24.0 (0.0) | 21.0 (1.73) | -* |

Note: numerical data presented as mean (SD).

aWilcoxon signed-rank test used to compare groups.

*Not possible to test due to missing data.

Participant experience

The three themes generated from participant exit interviews are detailed in Table 2, along with supporting quotes.

| Themes and subthemes . | Supporting quotes . |

|---|---|

| 1.Timely, accessible, multifaceted breastfeeding support is essential | |

| ‘we were able to text her and get communication…as we needed’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘I joined the [volunteer breastfeeding group] online, and that was really helpful actually as well, because they were kind of available twenty-four seven’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘It would be even better if I had her sooner, but it was Sunday, and she wasn't available’ (Intervention Group Participant 11) |

| ‘If it were not for [my partner], I…would not have breastfed’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) ‘There’s so many people that start breastfeeding. And then, they stop when they go home, because they do not have the support’ (Intervention Group Participant 17) |

| ‘I’m just really incredibly grateful that I got to be a part of it. I think it had a huge positive impact on, on breastfeeding and breastfeeding has just been like this total joy for me’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘it was really rough at first, but in the end it's turned out. I've done exclusively breastfeeding through to one year old...But I would say...being able to achieve that had absolutely nothing to do with any support.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) |

| ‘I did find it helped me in preparation for breastfeeding…just being…more familiar with...yourself and how your boobs work.’ (Intervention Group Participant 1) ‘he would not have…had any real knowledge or experience of breastfeeding…I think he found [the study class] very educational’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) |

| ‘I do not think that the being in the [intervention group] would have been any different. I had loads of really good support...when I needed it.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘as time went on, instead of getting easier things got harder, and there was, you know, a complete lack of support’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) |

| ‘I think it’s still very taboo in Ireland, and I think for older generations more so where I see, like my generation and the younger generation really starting to see, like the benefits of it, and that it’s okay’ (Intervention Group Participant 14) |

| 2. Publicly provided breastfeeding support is letting women down | |

| ‘someone… would tell you to do something, and someone else would tell you to do something else so it was just all very confusing.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 11) |

| ‘the moment things do not go according to plan in the hospital, they just immediately whip out the formula’ (Usual Care Group Participant 1) |

| ‘the midwives were no help in the hospital…[they] do not have the time to be there’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘the midwives were brilliant’ (Intervention Group Participant 6) |

| ‘The day support was overwhelmingly amazing. And then the night support was very um. Disappointing.’ (Intervention group participant 12) |

| ‘They have posters up all over the hospital to breastfeed, but when it comes to it, because the support is so bad, I do not, I’m not slagging them here. I just do not think they have the training’ (Intervention group participant 16—speaking about her experience with her second baby in a non-study Irish maternity centre) |

| ‘my GP never once addressed breastfeeding, and equally my Public Health Nurse actually never visited and um she vocalised that she did not have the knowledge and that she wasn't really able to support me with breastfeeding’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) ‘The best thing I found was the one-to-one with the lactation consultant from the public health care’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) |

| ‘the breastfeeding section was only a section of what we were learning from the day… So I just I think it was just such a small section. I did not really take any of it in.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 5) |

| 3. COVID-19 protected the fourth trimester and impacted breastfeeding experience | |

| ‘it gave you that lovely time to sort of bond without pressures of people visiting’ (Usual Care Group Participant 7) |

| ‘feeling that you giving some protection to the baby through breastfeeding, you know protection from Covid. It was really a positive’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘we were only two days home from the hospital, and I was able to go to a Cuidiú meeting because it was on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 6) ‘You definitely lose a lot trying to have a breast-feeding consultation on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘that sense of isolation...I think [COVID-19] had a pretty big impact, and I think it was compounded by the fact that we did not have any family around’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) ‘it made it easier in general, just because you are sort of stuck in and then staying home. So, you are available more’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘It...meant that [my partner] was working from home for some of the time, so he was able to provide more support’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) |

| Themes and subthemes . | Supporting quotes . |

|---|---|

| 1.Timely, accessible, multifaceted breastfeeding support is essential | |

| ‘we were able to text her and get communication…as we needed’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘I joined the [volunteer breastfeeding group] online, and that was really helpful actually as well, because they were kind of available twenty-four seven’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘It would be even better if I had her sooner, but it was Sunday, and she wasn't available’ (Intervention Group Participant 11) |

| ‘If it were not for [my partner], I…would not have breastfed’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) ‘There’s so many people that start breastfeeding. And then, they stop when they go home, because they do not have the support’ (Intervention Group Participant 17) |

| ‘I’m just really incredibly grateful that I got to be a part of it. I think it had a huge positive impact on, on breastfeeding and breastfeeding has just been like this total joy for me’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘it was really rough at first, but in the end it's turned out. I've done exclusively breastfeeding through to one year old...But I would say...being able to achieve that had absolutely nothing to do with any support.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) |

| ‘I did find it helped me in preparation for breastfeeding…just being…more familiar with...yourself and how your boobs work.’ (Intervention Group Participant 1) ‘he would not have…had any real knowledge or experience of breastfeeding…I think he found [the study class] very educational’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) |

| ‘I do not think that the being in the [intervention group] would have been any different. I had loads of really good support...when I needed it.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘as time went on, instead of getting easier things got harder, and there was, you know, a complete lack of support’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) |

| ‘I think it’s still very taboo in Ireland, and I think for older generations more so where I see, like my generation and the younger generation really starting to see, like the benefits of it, and that it’s okay’ (Intervention Group Participant 14) |

| 2. Publicly provided breastfeeding support is letting women down | |

| ‘someone… would tell you to do something, and someone else would tell you to do something else so it was just all very confusing.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 11) |

| ‘the moment things do not go according to plan in the hospital, they just immediately whip out the formula’ (Usual Care Group Participant 1) |

| ‘the midwives were no help in the hospital…[they] do not have the time to be there’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘the midwives were brilliant’ (Intervention Group Participant 6) |

| ‘The day support was overwhelmingly amazing. And then the night support was very um. Disappointing.’ (Intervention group participant 12) |

| ‘They have posters up all over the hospital to breastfeed, but when it comes to it, because the support is so bad, I do not, I’m not slagging them here. I just do not think they have the training’ (Intervention group participant 16—speaking about her experience with her second baby in a non-study Irish maternity centre) |

| ‘my GP never once addressed breastfeeding, and equally my Public Health Nurse actually never visited and um she vocalised that she did not have the knowledge and that she wasn't really able to support me with breastfeeding’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) ‘The best thing I found was the one-to-one with the lactation consultant from the public health care’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) |

| ‘the breastfeeding section was only a section of what we were learning from the day… So I just I think it was just such a small section. I did not really take any of it in.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 5) |

| 3. COVID-19 protected the fourth trimester and impacted breastfeeding experience | |

| ‘it gave you that lovely time to sort of bond without pressures of people visiting’ (Usual Care Group Participant 7) |

| ‘feeling that you giving some protection to the baby through breastfeeding, you know protection from Covid. It was really a positive’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘we were only two days home from the hospital, and I was able to go to a Cuidiú meeting because it was on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 6) ‘You definitely lose a lot trying to have a breast-feeding consultation on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘that sense of isolation...I think [COVID-19] had a pretty big impact, and I think it was compounded by the fact that we did not have any family around’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) ‘it made it easier in general, just because you are sort of stuck in and then staying home. So, you are available more’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘It...meant that [my partner] was working from home for some of the time, so he was able to provide more support’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) |

| Themes and subthemes . | Supporting quotes . |

|---|---|

| 1.Timely, accessible, multifaceted breastfeeding support is essential | |

| ‘we were able to text her and get communication…as we needed’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘I joined the [volunteer breastfeeding group] online, and that was really helpful actually as well, because they were kind of available twenty-four seven’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘It would be even better if I had her sooner, but it was Sunday, and she wasn't available’ (Intervention Group Participant 11) |

| ‘If it were not for [my partner], I…would not have breastfed’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) ‘There’s so many people that start breastfeeding. And then, they stop when they go home, because they do not have the support’ (Intervention Group Participant 17) |

| ‘I’m just really incredibly grateful that I got to be a part of it. I think it had a huge positive impact on, on breastfeeding and breastfeeding has just been like this total joy for me’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘it was really rough at first, but in the end it's turned out. I've done exclusively breastfeeding through to one year old...But I would say...being able to achieve that had absolutely nothing to do with any support.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) |

| ‘I did find it helped me in preparation for breastfeeding…just being…more familiar with...yourself and how your boobs work.’ (Intervention Group Participant 1) ‘he would not have…had any real knowledge or experience of breastfeeding…I think he found [the study class] very educational’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) |

| ‘I do not think that the being in the [intervention group] would have been any different. I had loads of really good support...when I needed it.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘as time went on, instead of getting easier things got harder, and there was, you know, a complete lack of support’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) |

| ‘I think it’s still very taboo in Ireland, and I think for older generations more so where I see, like my generation and the younger generation really starting to see, like the benefits of it, and that it’s okay’ (Intervention Group Participant 14) |

| 2. Publicly provided breastfeeding support is letting women down | |

| ‘someone… would tell you to do something, and someone else would tell you to do something else so it was just all very confusing.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 11) |

| ‘the moment things do not go according to plan in the hospital, they just immediately whip out the formula’ (Usual Care Group Participant 1) |

| ‘the midwives were no help in the hospital…[they] do not have the time to be there’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘the midwives were brilliant’ (Intervention Group Participant 6) |

| ‘The day support was overwhelmingly amazing. And then the night support was very um. Disappointing.’ (Intervention group participant 12) |

| ‘They have posters up all over the hospital to breastfeed, but when it comes to it, because the support is so bad, I do not, I’m not slagging them here. I just do not think they have the training’ (Intervention group participant 16—speaking about her experience with her second baby in a non-study Irish maternity centre) |

| ‘my GP never once addressed breastfeeding, and equally my Public Health Nurse actually never visited and um she vocalised that she did not have the knowledge and that she wasn't really able to support me with breastfeeding’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) ‘The best thing I found was the one-to-one with the lactation consultant from the public health care’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) |

| ‘the breastfeeding section was only a section of what we were learning from the day… So I just I think it was just such a small section. I did not really take any of it in.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 5) |

| 3. COVID-19 protected the fourth trimester and impacted breastfeeding experience | |

| ‘it gave you that lovely time to sort of bond without pressures of people visiting’ (Usual Care Group Participant 7) |

| ‘feeling that you giving some protection to the baby through breastfeeding, you know protection from Covid. It was really a positive’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘we were only two days home from the hospital, and I was able to go to a Cuidiú meeting because it was on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 6) ‘You definitely lose a lot trying to have a breast-feeding consultation on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘that sense of isolation...I think [COVID-19] had a pretty big impact, and I think it was compounded by the fact that we did not have any family around’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) ‘it made it easier in general, just because you are sort of stuck in and then staying home. So, you are available more’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘It...meant that [my partner] was working from home for some of the time, so he was able to provide more support’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) |

| Themes and subthemes . | Supporting quotes . |

|---|---|

| 1.Timely, accessible, multifaceted breastfeeding support is essential | |

| ‘we were able to text her and get communication…as we needed’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘I joined the [volunteer breastfeeding group] online, and that was really helpful actually as well, because they were kind of available twenty-four seven’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘It would be even better if I had her sooner, but it was Sunday, and she wasn't available’ (Intervention Group Participant 11) |

| ‘If it were not for [my partner], I…would not have breastfed’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) ‘There’s so many people that start breastfeeding. And then, they stop when they go home, because they do not have the support’ (Intervention Group Participant 17) |

| ‘I’m just really incredibly grateful that I got to be a part of it. I think it had a huge positive impact on, on breastfeeding and breastfeeding has just been like this total joy for me’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘it was really rough at first, but in the end it's turned out. I've done exclusively breastfeeding through to one year old...But I would say...being able to achieve that had absolutely nothing to do with any support.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) |

| ‘I did find it helped me in preparation for breastfeeding…just being…more familiar with...yourself and how your boobs work.’ (Intervention Group Participant 1) ‘he would not have…had any real knowledge or experience of breastfeeding…I think he found [the study class] very educational’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) |

| ‘I do not think that the being in the [intervention group] would have been any different. I had loads of really good support...when I needed it.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) ‘as time went on, instead of getting easier things got harder, and there was, you know, a complete lack of support’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) |

| ‘I think it’s still very taboo in Ireland, and I think for older generations more so where I see, like my generation and the younger generation really starting to see, like the benefits of it, and that it’s okay’ (Intervention Group Participant 14) |

| 2. Publicly provided breastfeeding support is letting women down | |

| ‘someone… would tell you to do something, and someone else would tell you to do something else so it was just all very confusing.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 11) |

| ‘the moment things do not go according to plan in the hospital, they just immediately whip out the formula’ (Usual Care Group Participant 1) |

| ‘the midwives were no help in the hospital…[they] do not have the time to be there’ (Intervention Group Participant 2) ‘the midwives were brilliant’ (Intervention Group Participant 6) |

| ‘The day support was overwhelmingly amazing. And then the night support was very um. Disappointing.’ (Intervention group participant 12) |

| ‘They have posters up all over the hospital to breastfeed, but when it comes to it, because the support is so bad, I do not, I’m not slagging them here. I just do not think they have the training’ (Intervention group participant 16—speaking about her experience with her second baby in a non-study Irish maternity centre) |

| ‘my GP never once addressed breastfeeding, and equally my Public Health Nurse actually never visited and um she vocalised that she did not have the knowledge and that she wasn't really able to support me with breastfeeding’ (Usual Care Group Participant 3) ‘The best thing I found was the one-to-one with the lactation consultant from the public health care’ (Usual Care Group Participant 8) |

| ‘the breastfeeding section was only a section of what we were learning from the day… So I just I think it was just such a small section. I did not really take any of it in.’ (Usual Care Group Participant 5) |

| 3. COVID-19 protected the fourth trimester and impacted breastfeeding experience | |

| ‘it gave you that lovely time to sort of bond without pressures of people visiting’ (Usual Care Group Participant 7) |

| ‘feeling that you giving some protection to the baby through breastfeeding, you know protection from Covid. It was really a positive’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘we were only two days home from the hospital, and I was able to go to a Cuidiú meeting because it was on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 6) ‘You definitely lose a lot trying to have a breast-feeding consultation on Zoom’ (Usual Care Group Participant 10) |

| ‘that sense of isolation...I think [COVID-19] had a pretty big impact, and I think it was compounded by the fact that we did not have any family around’ (Usual Care Group Participant 9) ‘it made it easier in general, just because you are sort of stuck in and then staying home. So, you are available more’ (Intervention Group Participant 15) |

| ‘It...meant that [my partner] was working from home for some of the time, so he was able to provide more support’ (Intervention Group Participant 7) |

Theme 1 is ‘Timely, accessible, multifaceted breastfeeding support is essential’. This reflects women’s need for a variety of forms of breastfeeding support, which should be easily accessible and available when required. Intervention participants reported an enjoyable experience establishing breastfeeding, whereas usual care participants felt they succeeded despite the odds and had to seek out support.

‘I suppose I went and got the intervention myself’ (usual care participant 6).

Positive experience of the intervention was reflected in the study feedback questionnaires. Over 50% reported the care provided by Latch On prepared them well/very well for breastfeeding (6 weeks n = 46 [61.3%]; 3 months n = 35 [50.7%]; 6 months n = 34 [58.6%]). 41.3% (n = 31) identified the one-to-one lactation assessment as the most helpful component.

Theme 2, ‘Publicly provided breastfeeding support is letting women down’, saw participants reporting mixed-to-negative experiences of public breastfeeding supports. Numerous deficiencies such as conflicting advice, using infant formula as a solution to breastfeeding problems, deficient breastfeeding knowledge and short staffing impacting support, and support not available outside office hours were all identified. Participants did not feel adequately prepared for breastfeeding following standard antenatal classes.

Theme 3 is ‘Covid-19 protected the fourth trimester and impacted breastfeeding experience’. Women reported that COVID-19 restrictions helped with establishing breastfeeding and bonding, although usual care participants expressed more feelings of isolation. Working from home enabled longer breastfeeding duration. Awareness of breastmilk’s immune benefits motivated participants to continue feeding during the pandemic. Online support was found to be an accessible addition to services but could not fully replace face-to-face support.

Health economic analysis

Summary data are presented for resource usage, costs for each resource category and health outcomes in Table 3. The Latch On intervention cost per participant is €157.00. Accurate cost analysis requires that each participant cost diary completed refers to the proceeding follow-up period in its entirety. A significant amount of cost diaries contained missing data so the total healthcare cost variable could not be calculated, and further analysis of cost effectiveness was not possible. Overall rate of cost diaries completion was 64.9% (n = 146) at 6 weeks, 59.1% (n = 133) at 3 months i.e. week 7 to week 12 inclusive and 51.1% (n = 114) at 6 months i.e. week 13 to week 24 inclusive. At 3 months the total cost (general practitioner [GP] visits for women, GP visits for baby, Private lactation consultant and Latch On intervention costs) data was reported by 27 participants in the Intervention group and 35 in the usual care group. The intervention was associated with an increase in cost of €91.65 at 3 months, which is due to inclusion of the intervention cost of €157.00 for the group who received it. Results from analysis controlling for study site and overweight/obese are presented in the Supplementary Appendix.

| Resource item . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 (6 weeks) Weeks 1 to 6 Mean (SD) | Time 2 (3 months) Weeks 7 to 12 Mean (SD) | Time 3 (6 months) Weeks 13 to 24 Mean (SD) | ||||

| GP visits - mother (usage) | 1.85 (1.79) n = 67 | 1.98 (2.13) n = 63 | 1.71 (1.15) n = 59 | 1.83 (1.80) n = 58 | 1.93 (1.67) n = 55 | 1.71 (1.93) n = 49 |

| GP visits - mother (costs) | €96.24 (92.87) n = 67 | €103.17 (110.71) n = 63 | €89.02 (59.56) n = 59 | €95.03 (93.50) n = 58 | €100.22 (86.58) n = 55 | €89.14 (100.14) n = 49 |

| GP visits - baby (usage) | 1.79 (1.08) n = 67 | 2.19 (1.74) n = 64 | 3.12 (1.78) n = 59 | 3.11 (1.93) n = 61 | 3.62 (1.91) n = 54 | 3.42 (1.69) n = 52 |

| GP visits - baby (costs) | €93.13 (56.19) n = 67 | €113.75 (90.72) n = 64 | €162.17 (92.66) n = 59 | €161.97 (110.51) n = 61 | €180.07 (87.90) n = 54 | €188.00 (99.39) n = 52 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (usage) | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 | 1.19 (1.56) n = 37 | 0.83 (2.08) n = 27 | 1.05 (1.33) n = 37 | 0.35 (0.83) n = 28 | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (costs) | €16.78 (33.00) n = 30 | €63.03 (72.71) n = 37 | €44.17 (110.25) n = 27 | €55.86 (70.61) n = 37 | €18.93 (43.79) n = 28 | €41.89 (63.37) n = 30 |

| Latch On programme intervention cost | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 |

| Total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) | €364.45(121.64) n = 30 | €271.60(189.41) n = 35 | €409.17(169.57) n = 27 | €317.51(181.59) n = 35 | €447.07(140.53) n = 28 | €311.92(172.56) n = 30 |

| Difference in mean total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) (95% CI) [P-value] | €91.65 (1.97, 181.34) [0.045] n = 62 | €135.15 (52.58, 217.73) [0.002] n = 58 | ||||

| Health Outcomes | ||||||

| EQ-5D-5L index score | 0.821 (0.196) n = 76 | 0.835 (0.218) n = 72 | 0.871 (0.150) n = 68 | 0.883 (0.142) n = 71 | 0.908 (0.131) n = 62 | 0.875 (0.190) n = 61 |

| QALYs gained | 0.095 (0.023) n = 76 | 0.096 (0.025) n = 72 | 0.211 (0.035) n = 65 | 0.213 (0.045) n = 66 | 0.431 (0.059) n = 58 | 0.437 (0.070) n = 57 |

| Difference in mean QALYs at 3 months (95% CI) [P-value] | −0.003 (−0.017, 0.011) [0.705] n = 131 | −0.006 −0.030, 0.018 [0.608] n = 115 | ||||

| Resource item . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 (6 weeks) Weeks 1 to 6 Mean (SD) | Time 2 (3 months) Weeks 7 to 12 Mean (SD) | Time 3 (6 months) Weeks 13 to 24 Mean (SD) | ||||

| GP visits - mother (usage) | 1.85 (1.79) n = 67 | 1.98 (2.13) n = 63 | 1.71 (1.15) n = 59 | 1.83 (1.80) n = 58 | 1.93 (1.67) n = 55 | 1.71 (1.93) n = 49 |

| GP visits - mother (costs) | €96.24 (92.87) n = 67 | €103.17 (110.71) n = 63 | €89.02 (59.56) n = 59 | €95.03 (93.50) n = 58 | €100.22 (86.58) n = 55 | €89.14 (100.14) n = 49 |

| GP visits - baby (usage) | 1.79 (1.08) n = 67 | 2.19 (1.74) n = 64 | 3.12 (1.78) n = 59 | 3.11 (1.93) n = 61 | 3.62 (1.91) n = 54 | 3.42 (1.69) n = 52 |

| GP visits - baby (costs) | €93.13 (56.19) n = 67 | €113.75 (90.72) n = 64 | €162.17 (92.66) n = 59 | €161.97 (110.51) n = 61 | €180.07 (87.90) n = 54 | €188.00 (99.39) n = 52 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (usage) | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 | 1.19 (1.56) n = 37 | 0.83 (2.08) n = 27 | 1.05 (1.33) n = 37 | 0.35 (0.83) n = 28 | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (costs) | €16.78 (33.00) n = 30 | €63.03 (72.71) n = 37 | €44.17 (110.25) n = 27 | €55.86 (70.61) n = 37 | €18.93 (43.79) n = 28 | €41.89 (63.37) n = 30 |

| Latch On programme intervention cost | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 |

| Total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) | €364.45(121.64) n = 30 | €271.60(189.41) n = 35 | €409.17(169.57) n = 27 | €317.51(181.59) n = 35 | €447.07(140.53) n = 28 | €311.92(172.56) n = 30 |

| Difference in mean total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) (95% CI) [P-value] | €91.65 (1.97, 181.34) [0.045] n = 62 | €135.15 (52.58, 217.73) [0.002] n = 58 | ||||

| Health Outcomes | ||||||

| EQ-5D-5L index score | 0.821 (0.196) n = 76 | 0.835 (0.218) n = 72 | 0.871 (0.150) n = 68 | 0.883 (0.142) n = 71 | 0.908 (0.131) n = 62 | 0.875 (0.190) n = 61 |

| QALYs gained | 0.095 (0.023) n = 76 | 0.096 (0.025) n = 72 | 0.211 (0.035) n = 65 | 0.213 (0.045) n = 66 | 0.431 (0.059) n = 58 | 0.437 (0.070) n = 57 |

| Difference in mean QALYs at 3 months (95% CI) [P-value] | −0.003 (−0.017, 0.011) [0.705] n = 131 | −0.006 −0.030, 0.018 [0.608] n = 115 | ||||

Healthcare resource use was costed using Euro 2020 unit cost prices. Source of cost was Smith et al. (2021) for GP visit and study records for Private Lactation Consultant visit.44 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, EQ-5D-5L index score = EuroQol 5 dimension 5 level health status measure score, GP = general practitioner.

| Resource item . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 (6 weeks) Weeks 1 to 6 Mean (SD) | Time 2 (3 months) Weeks 7 to 12 Mean (SD) | Time 3 (6 months) Weeks 13 to 24 Mean (SD) | ||||

| GP visits - mother (usage) | 1.85 (1.79) n = 67 | 1.98 (2.13) n = 63 | 1.71 (1.15) n = 59 | 1.83 (1.80) n = 58 | 1.93 (1.67) n = 55 | 1.71 (1.93) n = 49 |

| GP visits - mother (costs) | €96.24 (92.87) n = 67 | €103.17 (110.71) n = 63 | €89.02 (59.56) n = 59 | €95.03 (93.50) n = 58 | €100.22 (86.58) n = 55 | €89.14 (100.14) n = 49 |

| GP visits - baby (usage) | 1.79 (1.08) n = 67 | 2.19 (1.74) n = 64 | 3.12 (1.78) n = 59 | 3.11 (1.93) n = 61 | 3.62 (1.91) n = 54 | 3.42 (1.69) n = 52 |

| GP visits - baby (costs) | €93.13 (56.19) n = 67 | €113.75 (90.72) n = 64 | €162.17 (92.66) n = 59 | €161.97 (110.51) n = 61 | €180.07 (87.90) n = 54 | €188.00 (99.39) n = 52 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (usage) | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 | 1.19 (1.56) n = 37 | 0.83 (2.08) n = 27 | 1.05 (1.33) n = 37 | 0.35 (0.83) n = 28 | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (costs) | €16.78 (33.00) n = 30 | €63.03 (72.71) n = 37 | €44.17 (110.25) n = 27 | €55.86 (70.61) n = 37 | €18.93 (43.79) n = 28 | €41.89 (63.37) n = 30 |

| Latch On programme intervention cost | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 |

| Total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) | €364.45(121.64) n = 30 | €271.60(189.41) n = 35 | €409.17(169.57) n = 27 | €317.51(181.59) n = 35 | €447.07(140.53) n = 28 | €311.92(172.56) n = 30 |

| Difference in mean total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) (95% CI) [P-value] | €91.65 (1.97, 181.34) [0.045] n = 62 | €135.15 (52.58, 217.73) [0.002] n = 58 | ||||

| Health Outcomes | ||||||

| EQ-5D-5L index score | 0.821 (0.196) n = 76 | 0.835 (0.218) n = 72 | 0.871 (0.150) n = 68 | 0.883 (0.142) n = 71 | 0.908 (0.131) n = 62 | 0.875 (0.190) n = 61 |

| QALYs gained | 0.095 (0.023) n = 76 | 0.096 (0.025) n = 72 | 0.211 (0.035) n = 65 | 0.213 (0.045) n = 66 | 0.431 (0.059) n = 58 | 0.437 (0.070) n = 57 |

| Difference in mean QALYs at 3 months (95% CI) [P-value] | −0.003 (−0.017, 0.011) [0.705] n = 131 | −0.006 −0.030, 0.018 [0.608] n = 115 | ||||

| Resource item . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . | Intervention N = 112 . | Control N = 113 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 (6 weeks) Weeks 1 to 6 Mean (SD) | Time 2 (3 months) Weeks 7 to 12 Mean (SD) | Time 3 (6 months) Weeks 13 to 24 Mean (SD) | ||||

| GP visits - mother (usage) | 1.85 (1.79) n = 67 | 1.98 (2.13) n = 63 | 1.71 (1.15) n = 59 | 1.83 (1.80) n = 58 | 1.93 (1.67) n = 55 | 1.71 (1.93) n = 49 |

| GP visits - mother (costs) | €96.24 (92.87) n = 67 | €103.17 (110.71) n = 63 | €89.02 (59.56) n = 59 | €95.03 (93.50) n = 58 | €100.22 (86.58) n = 55 | €89.14 (100.14) n = 49 |

| GP visits - baby (usage) | 1.79 (1.08) n = 67 | 2.19 (1.74) n = 64 | 3.12 (1.78) n = 59 | 3.11 (1.93) n = 61 | 3.62 (1.91) n = 54 | 3.42 (1.69) n = 52 |

| GP visits - baby (costs) | €93.13 (56.19) n = 67 | €113.75 (90.72) n = 64 | €162.17 (92.66) n = 59 | €161.97 (110.51) n = 61 | €180.07 (87.90) n = 54 | €188.00 (99.39) n = 52 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (usage) | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 | 1.19 (1.56) n = 37 | 0.83 (2.08) n = 27 | 1.05 (1.33) n = 37 | 0.35 (0.83) n = 28 | 0.32 (0.62) n = 30 |

| Private lactation consultant visits (costs) | €16.78 (33.00) n = 30 | €63.03 (72.71) n = 37 | €44.17 (110.25) n = 27 | €55.86 (70.61) n = 37 | €18.93 (43.79) n = 28 | €41.89 (63.37) n = 30 |

| Latch On programme intervention cost | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 | €157.00 (0.00) n = 112 | €0.00 (0.00) n = 113 |

| Total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) | €364.45(121.64) n = 30 | €271.60(189.41) n = 35 | €409.17(169.57) n = 27 | €317.51(181.59) n = 35 | €447.07(140.53) n = 28 | €311.92(172.56) n = 30 |

| Difference in mean total cost (GP mother + GP baby + Latch On programme + private lactation consultant) (95% CI) [P-value] | €91.65 (1.97, 181.34) [0.045] n = 62 | €135.15 (52.58, 217.73) [0.002] n = 58 | ||||

| Health Outcomes | ||||||

| EQ-5D-5L index score | 0.821 (0.196) n = 76 | 0.835 (0.218) n = 72 | 0.871 (0.150) n = 68 | 0.883 (0.142) n = 71 | 0.908 (0.131) n = 62 | 0.875 (0.190) n = 61 |

| QALYs gained | 0.095 (0.023) n = 76 | 0.096 (0.025) n = 72 | 0.211 (0.035) n = 65 | 0.213 (0.045) n = 66 | 0.431 (0.059) n = 58 | 0.437 (0.070) n = 57 |

| Difference in mean QALYs at 3 months (95% CI) [P-value] | −0.003 (−0.017, 0.011) [0.705] n = 131 | −0.006 −0.030, 0.018 [0.608] n = 115 | ||||

Healthcare resource use was costed using Euro 2020 unit cost prices. Source of cost was Smith et al. (2021) for GP visit and study records for Private Lactation Consultant visit.44 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, EQ-5D-5L index score = EuroQol 5 dimension 5 level health status measure score, GP = general practitioner.

The primary clinical health outcome was the number and percentage of women still breastfeeding at 3 months follow up. These estimates were 68 (68.7%) for the intervention and 59 (62.1%) for usual care. The mean QALYs gained at 3 months estimates were 0.21 (standard deviation [SD] 0.035) for the intervention and 0.213 (SD 0.045) for usual care, which did not differ.

Discussion

Main findings of this study

We found that intervention normalization resulted in provision of follow-up breastfeeding services in two study centres after study completion. Themes explored in participant exit interviews revealed the importance of improving public breastfeeding supports and described the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the breastfeeding experience. Within Theme 1, intervention participants described a more enjoyable breastfeeding experience compared to control participants, showing a beneficial effect of the intervention despite similar breastfeeding rates between groups.

The study was delivered with fidelity, and the intervention dose received influenced early breastfeeding outcomes. Health outcomes including number and percentage of women breastfeeding, EQ-5D-5L Index Score and QALYs did not significantly differ between groups at 3 months. We estimated the intervention cost at €157.00 per participant.

What is already known on this topic

The need for increased breastfeeding support for all women is supported by recent Irish11 and international data.33 High-quality breastfeeding support studies in women with overweight and obesity are limited,12,34 but systematic review shows provision of support does increase breastfeeding rates in this population.12 Single- and multi-component breastfeeding education and support interventions have proven effective in healthy populations.35–37 Further high quality, large-scale studies of such interventions are required for women with overweight and obesity, as well as the general population.37,38 Cost-effectiveness studies of breastfeeding supports to date are very limited,39 and direct cost comparison between interventions is difficult due to heterogeneity.40

What this study adds

We demonstrated benefits from providing comprehensive breastfeeding education and support. Intervention dose received made a difference to short-term outcomes, and the intervention improved the breastfeeding experience for those who received it. We found that full implementation of an intervention such as Latch On is currently limited by staffing levels, but drop-in breastfeeding clinics may be an achievable way to provide ongoing support in the early postnatal period until resourcing is improved.

Breastfeeding self-efficacy is an important contributor to breastfeeding success,41 and antenatally is an under-researched area.42 Our usual care group had high breastfeeding rates compared with national averages and the whole cohort had high breastfeeding intention and motivation at baseline.15 Enrolling in a breastfeeding support study may have a positive effect on self-efficacy or may reflect higher pre-existing self-efficacy. Role-modelling, one of the four pillars of self-efficacy, could be positively influenced by observing women of larger BMIs successfully breastfeeding.43 Role-modelling was intentionally included in the Latch On class but may have also affected the usual care group via study promotion materials. Antenatal discussion of breastfeeding, promotion of breastfeeding education and use of inclusive imagery in educational materials could all be considered as potential methods of improving self-efficacy, and therefore breastfeeding outcomes.42

The full Latch On multi-component intervention cost is similar to a single private lactation consult.45,46 A definitive assessment of cost effectiveness was not possible due to missing resource use data, and as a result our findings should be interpreted as equivocal rather than as suggestive of cost effectiveness. However, the international evidence base does appear to support the broader cost-saving potential of breastfeeding.47–49

Limitations of this study

We recruited women interested in breastfeeding, and therefore our results may not be applicable to those with lower breastfeeding intention. Our planned cost effectiveness analysis was limited by substantial missing data. The more enjoyable breastfeeding experience reported by the intervention participants at exit interviews did not translate to a difference between groups in breastfeeding rates or QALYs. However, missing data, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on participant wellbeing or unknown other factors may have influenced broader health outcomes.

Study design may have limited our outcomes, as support partners were recruited for all participants, and usual care participants received care from the same IBCLCs as intervention participants. This may have caused some dilution of the intervention effect. A cluster RCT design could have overcome this.

Our study cohort was relatively homogenous in ethnicity, socio-economic status and education level.15 The findings may have limited applicability to populations with differing characteristics, as well as to those who do not identify as women.

Conclusion

The Latch On intervention improved participant breastfeeding experience, and receiving adequate intervention dose resulted in short-term improvements in breastfeeding rates. Intervention normalization resulted in ongoing changes to breastfeeding support services in half of study sites. Intervention effectiveness at primary outcome level was not demonstrated by our data, but other publications have shown that improving education and support does improve breastfeeding rates. Participant exit interview findings highlight how important breastfeeding support is for women. The intervention was low cost to deliver, but more definitive evidence would be required to judge its potential to achieve significant long-term cost savings to the health service and economy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Latch On Consortium. The members were Ms Denise McGuinness, Dr Sarah Louise Killeen, Dr John Mehegan, Prof. Barbara Coughlan, Dr Eileen C. O’Brien, Dr Marie Conway, Dr Denise O’Brien, Ms Marcelina Szafranska, Ms Mary Brosnan, Ms Lucille Sheehy, Ms Rosie Murtagh, Ms Lorraine O’Hagan, Ms Marie Corbett, Ms Michelle Walsh, Ms Regina Keogh, Ms Paula Power, Ms Marie Woodcock, Ms Mary Phelan, Ms Amy Carroll, Ms Stephanie Murray, Ms Charmaine Scallan and Prof. Elizabeth Dunn.

Funding

This work was supported by the HSE Nursing and Midwifery Planning and Development Unit Dublin South, Kildare and Wicklow. The funders had no role in study design or analysis. No grant numbers were awarded.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Dr. Catherine McNestry, MRCPI, MRCOG

Dr. Anna Hobbins, PhD

Ms. Niamh Donnellan, BSc

Prof. Paddy Gillespie, PhD

Prof. Fionnuala M. McAuliffe, FRCPI, FRCOG, MD

Prof. Sharleen L. O’Reilly, PhD

References

McGovern L, Geraghty A, McAuliffe F. et al.