-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ana Aguiar, Mariana Abreu, Raquel Duarte, Healthcare professionals perspectives on tuberculosis barriers in Portuguese prisons—a qualitative study, Journal of Public Health, Volume 46, Issue 3, September 2024, Pages e389–e399, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdae065

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health concern, particularly within prison settings, where the confluence of adverse health factors and high-risk behaviors contribute to a heightened risk of transmission. This study delves into the perspectives of medical doctors, regarding the implementation of the 2014 TB protocol in Portugal.

The study has a qualitative, descriptive design. Individual semi-structured interviews with medical doctors from TB outpatient centers in Porto and Lisbon were used for data collection. For the analysis thematic analysis method was used.

The study population comprised 21 medical doctors with the majority being female (61.9%) and 57.1% specializing in pulmonology. The results indicate varied perceptions of the protocol’s usefulness, with positive impacts on coordination reported by some participants. Improved communication and evolving collaboration between TB outpatient centers and prisons were highlighted, although challenges in contact tracing and resource constraints were acknowledged. The study also sheds light on the role of nurses in patient education.

Despite overall positive perceptions, challenges such as sustaining therapy post-symptomatic improvement and delays in diagnostic methods were identified. The findings underscore the importance of continuous collaboration between prisons and TB control programs to address challenges, improve disease control and prevent TB transmission.

Background

Despite the declining tuberculosis (TB) cases globally, it remains a significant public health concern, causing considerable illness and death.1 Controlling TB in prisons is uniquely challenging due to the specific epidemiological context.2 People deprived of liberty (PDL) exhibit a higher prevalence of infectious diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B hepatitis C, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia and TB, compared to the general population.3,4 Many of these individuals, often from disadvantaged backgrounds—a recognized TB risk factor—are increasingly immigrants or part of ethnic minority groups with higher TB prevalence.5 Adverse health factors and unstable living conditions within correctional facilities, such as sedentary lifestyles, inadequate diets and poor hygiene, significantly contribute to the spread of infectious diseases among incarcerated individuals.6

Additionally, PDL often engages in health-risk behaviors such as alcoholism,7 smoking,8 and drug abuse,9 which are also associated with an increased risk of TB.10 Consequently, both the risk of contracting TB upon entering the prison system and the risk of TB transmission within prison, whether the disease is already present or not, are significantly higher among PDL compared to the general population.11 Latent tuberculosis and active TB in prisons are significantly more common than in the general population, irrespective of a country’s economic status or overall TB burden.12 In European prisons, the estimated prevalence of TB is noted to be up to 17 times greater than that in the general population.13

Screening for TB in prison settings presents a formidable challenge; therefore, emphasis should be placed on early diagnosis and effective treatment.14 To prevent treatment interruptions and recurrence, closely monitor PDLs with active TB through the healthcare system. Implement vital policies, programs and strategies outlined in ‘The Global Plan to Stop TB 2016–2020,’ including screening for respiratory symptoms, examining contacts, culture and susceptibility testing, diagnosing co-infections, employing directly observed therapy and educational initiatives. These actions are crucial for achieving the goal of eradicating TB by 2030.14–16

Beyond outlined PDL epidemiological factors, TB transmission in prisons is worsened by suboptimal cell conditions—poor ventilation, overcrowding and frequent cell changes for security. Challenges in early diagnosis and rapid PDL turnover heighten TB transmission risks.3,17,18 Global literature links rising incarceration rates to TB incidence, with the inmate population growth rate key to prison TB.19,20 Prison conditions facilitate TB transmission to both inmates and the wider community, including workers, visitors and released individuals, especially when treatment is incomplete or poorly monitored.4,5,8,9 World Health Organization (WHO) notes higher multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) rates in prisons than in the general community21; in some European prisons, MDR-TB accounts for 24% of cases.22

TB in prisons affects the broader community, emphasizing the need for connections between prisons and international, national and local TB control programs. Despite extensive TB literature, a research gap exists in understanding barriers to TB detection in prisons. Global implementation of TB control faces challenges due to complex obstacles linked to healthcare, justice systems and country-specific factors. These barriers, categorized as behavioral and structural, involve the actions of PDL, guards, healthcare professionals, infrastructure and policies within prisons.17,18

In Portugal, 49 prisons are divided across Porto, Coimbra, Lisbon and Évora into male, female and mixed facilities. Individuals deprived of their liberty are entitled to healthcare services of at least equivalent quality to those available to the free community. The healthcare provided adheres to guidelines and norms issued by the Portuguese General Health Directorate (DGS). Primary care services, including specialized ones like psychiatry and dentistry, are available in Portuguese prisons. Specialized cases are referred to the National Health Service. Healthcare, provided free of charge, includes assessments within 24 hours and screenings for diseases like HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and TB. Positive cases are referred to local hospitals, and TB assessments involve X-ray examinations, handled by mobile units with the prison system responsible for notifications. Moreover, screening for sexually transmitted infections, dental problems and substance use, including alcohol, is performed. Nurses observe withdrawal symptoms, referring cases promptly to physicians. Oncological screening, based on age and sex, follows approved guidelines. Upon admission, healthcare professionals contact Portuguese National Health Service providers for essential health data.

Concerning TB, in 2014, the DGS reported 51 TB cases among PDLs, comprising 2.5% of national cases, underscoring their susceptibility. The prisoners’ TB incidence was 385 per 100 000, much higher than the general population’s 20 per 100 000. In the same year, the National Tuberculosis Program agreement was signed between the DGS and the General Directorate of Reinsertion and Prison Services (DGRSP) to standardize TB detection in prisons. The protocol mandated active TB case searches, defined procedures and timelines for follow-up, mobile radiography units for screening, public funding for private sector examinations and a three-stage TB screening approach. This included entry screening, regular 6-month screenings for all PDL and comprehensive contact tracing. The agreement aimed to improve communication between prison and community health services, establish best practices for contact tracing and create a collaborative technical committee to coordinate and evaluate protocol implementation.23 Moreover, the national protocol outlines regular TB screening upon entry and at periodic intervals within facilities. It emphasizes the isolation of individuals suspected or confirmed to have TB, implementation of infection prevention and control measures, and the provision of proper diagnosis and treatment for TB, extending to prison settings.

Although initially lacked uniformity, the impact of the protocol impact is already evident in the decreasing number of secondary cases within prisons or related to prison settings.23

According to the most recent available statistics, there were 24 cases of TB in prison settings (1.6% of all cases) in 2020, equating to a notification rate in this population of 210.3/100 000 (for a total of 11.412 inmates).24 Moreover, by December 2022, Portugal had 12.198 PDL, corresponding to an occupation rate of 96.3%.25

Therefore, the study aimed to understand the perspectives of medical doctors regarding the coordination between prison establishments and TB outpatient centers in Porto and Lisbon districts to study their perceptions about implementing the 2014 TB protocol that standardizes TB detection and prevention procedures within correctional facilities.

Methods

For the present study, data collection and analysis were grounded in qualitative methods, including interviews conducted with medical specialists from the TB outpatient centers—structures responsible for the TB approach in ambulatory care—in the designated study areas in Portugal.

Participants and study location

The participants were specialist doctors working in the TB outpatient center of the districts of Porto (Amarante, Gondomar, Gaia, Maia, Matosinhos, Paços de Ferreira, Penafiel, Porto and Santo Tirso) and Lisbon (Cascais, Torres Vedras, Ribeiro Sanches, Venda Nova and Vila Franca de Xira). Although other individuals play crucial roles in TB control, the protocol primarily emphasizes physicians’ procedures. They bear the responsibility for overseeing TB patients, ensuring accurate diagnosis and overseeing treatment, including monitoring potential side effects and ensuring medication adherence. Therefore, our sample is composed only by medical doctors.

Moreover, we aimed to interview as many specialist doctors as feasible to gather a comprehensive range of opinions on the subject of study, striving to reach a point of theoretical saturation.

Data collection methods

Data collection involved face-to-face semi-structured interviews using a script informed by TB experts and the established protocol. The guide included participant characteristics (gender, age, specialization and years of TB experience, especially in outpatient centers). It addressed topics such as the coordination model between TB outpatient centers and prison establishments (PE), tuberculosis diagnosis and monitoring during and after imprisonment, and the doctor–patient relationship.

Participants received information about the study objectives and then provided written consent, and all data was treated anonymously. Each participant was assigned a unique identification code comprising letters for Porto and Lisbon districts and numbers for the specific TB outpatient center. Only the researcher responsible for data collection (MP) and research team members (AA and RD), all women, had access to the interview material.

Qualitative analysis

Between May and June 2018, interviews were conducted with specialist doctors from the TB outpatient centers under investigation. The Coordinators of Regional Offices of the National Tuberculosis Program were initially contacted via email to inform them about the study. Upon receiving consent, MA scheduled interview appointments through email and phone communication. The interviews were audio-recorded and took place at the respective TB outpatient centers.

The interview data was recorded and transcribed verbatim. Employing an inductive approach, a thematic analysis framework was developed to categorize themes, subthemes and emerging categories from participants’ spontaneous narratives. Following the protocol outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006), the thematic analysis was manually conducted.26 MA did the first coding and they discussed with the rest of the team, making further adjustments in order to achieve trustworthiness.

Ethics

Two ethic entities approved the project: the Ethical Committee of the Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto, where the study was conducted (reference: CE17073b), and the Ethical Committee of the Regional Health Administration of Lisbon (reference: 13969/CES/2017). Every stage of this study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, which is applicable worldwide. All documents related to this study were securely stored and protected with encryption using a password.

Results

Out of 35 specialist doctors, 21 were interviewed successfully. Regrettably, it was impractical to interview specialists from two TB outpatient centers in the Lisbon district, comprising three individuals. During the interview, three doctors declined participation, and seven were unavailable due to their absence from work. Consequently, the overall participation rate stood at 60%. Even though, data saturation was achieved after 15 interviews.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The study predominantly included female participants (61.9%), with 57.1% specializing in Pulmonology. Participants in the Porto district were generally younger, with a median age of 49, compared to 63 years in the Lisbon district. Concerning their tenure at the TB outpatient center, 47.6% had held their positions for 15 years or more. Regarding total working time at the study TB outpatient center, over half of the professionals had less than 10 years of experience. In Lisbon, 60% of participants worked at the TB outpatient center study for less than a year and in Porto, responses were more distributed across various employment durations.

Thematic analysis

Table 1 displays the themes, subthemes and categories derived from the thematic analysis. Gender and age at time of interview are reported for all quotations.

Themes, subthemes and categories of thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews

| Theme . | Sub-theme . | Category . | Theme definition . | Citations examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Perceptions about the protocol | Perceptions about the usefulness of the protocol | This topic aims to understand the participants’ level of knowledge about the protocol and its usefulness | ‘The protocol aims to ensure that there are no outbreaks of tuberculosis in prisons (...)’ (female, 45 years old) | |

| Perceptions about protocol knowledge | ‘Protocol no, I don’t know (...) I don’t know about this protocol (...) Does it exist, by the way?’ (male, 57 years old) | |||

| Insights into the protocol domain | ‘(...) to perceive if the patient is ill or not, by doing an initial screening for the disease. And then repeat this screening every year to make sure there are no new cases of tuberculosis. In other words, screening on entry and then, in theory, annually, according to the profile of the cases. There is also the possibility of screening for latent tuberculosis, but the disease is the priority in this regard.’ (female, 45 years old) | |||

| 2) Articulation between TB outpatient center and prison establishment | Appreciation of articulation and factors influencing articulation | This theme aims to understand the participant’s relationship with the PE with whom they articulate and what factors influence this relationship | ‘(...) difficult... difficult to communicate (...) there is a lack of communication, whenever there is a request for information, there is usually little feedback. Whenever problems are detected and we try to clarify and help resolve them, we can’t get through (...)’ (female, 47 years old) | |

| Relationship with PE-health professionals | Procedures | ‘(...) I always spoke to my colleague (...) always to the same person... it always went very well. We quickly realised what each other wanted and... everything went very smoothly. It’s a good relationship, I’ve never had any difficulties (...) friendly, respectful, and from a professional point of view, really professional, always trying to solve the problems we had, both on my part and on my colleague’s part (...) It was always the same” (male, 54 years old) | ||

| Perceptions about the inter-institutional articulation between PE and PDC | Evolution of the articulation | ‘The first contact I use is always the cell phone (…) either via WhatsApp (…) if I can’t reach them, it will be via email’ (female, 65 years old) | ||

| 3) Diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis | Contact tracing | This theme aims to understand the process of diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis, from entry into the PE to the exit from the PE, in which institutions are involved, and the appreciation of the articulation between these | ‘Not in a situation of imprisonment’ ou ‘not during detention/imprisonment’ (male, 58 years) | |

| Perceptions about the liberation process and/or transfer of a prisoner with tuberculosis | ‘(...) one of the problems is the lack of human resources (...) we’re increasingly trying to get colleagues out into the field, internal colleagues and even other professionals, because we need to. We have to mobilise more human resources and not just doctors, because nurses play a fundamental role here...in records and assessments and even in talking to patients (...)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Education of the inmate or ex-prisoner patient | Perception of the level of literacy about tuberculosis before the first consultation at the PDC | ‘(...) Neither prisoners nor non-prisoners! People aren’t educated about anything! (...) They have no knowledge about the disease (...) the dangers they face(...)’ (male, 58 years) | ||

| Patient education at PDC | ‘It’s me, it’s us (…) usually me and the nurse (…)’ (male, 58 years) | |||

| Written information about tuberculosis to give to the patient | ‘No (…) we had phases in which we had brochures and gave them to everyone, now we are in a phase of reevaluating what is written (…)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Perceptions about the process of monitoring incarcerated patients | Diagnosis | ‘(…) the diagnosis is usually made when they are already in a very advanced situation (…) because they are not patients who easily comply with rules, nor do they adjust, they wait a long time and until they have symptoms and really already sick people come to ask for help.’ (female, 43 years) | ||

| Prevention | ‘(…) The problem appears later when they are better, because then we have more problems so that they continue to do things in a regulated way and then have follow-up (…) and prevention is obviously always difficult, because they feel good and therefore do not see the need to do anything else.’ (female, 43 years) |

| Theme . | Sub-theme . | Category . | Theme definition . | Citations examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Perceptions about the protocol | Perceptions about the usefulness of the protocol | This topic aims to understand the participants’ level of knowledge about the protocol and its usefulness | ‘The protocol aims to ensure that there are no outbreaks of tuberculosis in prisons (...)’ (female, 45 years old) | |

| Perceptions about protocol knowledge | ‘Protocol no, I don’t know (...) I don’t know about this protocol (...) Does it exist, by the way?’ (male, 57 years old) | |||

| Insights into the protocol domain | ‘(...) to perceive if the patient is ill or not, by doing an initial screening for the disease. And then repeat this screening every year to make sure there are no new cases of tuberculosis. In other words, screening on entry and then, in theory, annually, according to the profile of the cases. There is also the possibility of screening for latent tuberculosis, but the disease is the priority in this regard.’ (female, 45 years old) | |||

| 2) Articulation between TB outpatient center and prison establishment | Appreciation of articulation and factors influencing articulation | This theme aims to understand the participant’s relationship with the PE with whom they articulate and what factors influence this relationship | ‘(...) difficult... difficult to communicate (...) there is a lack of communication, whenever there is a request for information, there is usually little feedback. Whenever problems are detected and we try to clarify and help resolve them, we can’t get through (...)’ (female, 47 years old) | |

| Relationship with PE-health professionals | Procedures | ‘(...) I always spoke to my colleague (...) always to the same person... it always went very well. We quickly realised what each other wanted and... everything went very smoothly. It’s a good relationship, I’ve never had any difficulties (...) friendly, respectful, and from a professional point of view, really professional, always trying to solve the problems we had, both on my part and on my colleague’s part (...) It was always the same” (male, 54 years old) | ||

| Perceptions about the inter-institutional articulation between PE and PDC | Evolution of the articulation | ‘The first contact I use is always the cell phone (…) either via WhatsApp (…) if I can’t reach them, it will be via email’ (female, 65 years old) | ||

| 3) Diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis | Contact tracing | This theme aims to understand the process of diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis, from entry into the PE to the exit from the PE, in which institutions are involved, and the appreciation of the articulation between these | ‘Not in a situation of imprisonment’ ou ‘not during detention/imprisonment’ (male, 58 years) | |

| Perceptions about the liberation process and/or transfer of a prisoner with tuberculosis | ‘(...) one of the problems is the lack of human resources (...) we’re increasingly trying to get colleagues out into the field, internal colleagues and even other professionals, because we need to. We have to mobilise more human resources and not just doctors, because nurses play a fundamental role here...in records and assessments and even in talking to patients (...)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Education of the inmate or ex-prisoner patient | Perception of the level of literacy about tuberculosis before the first consultation at the PDC | ‘(...) Neither prisoners nor non-prisoners! People aren’t educated about anything! (...) They have no knowledge about the disease (...) the dangers they face(...)’ (male, 58 years) | ||

| Patient education at PDC | ‘It’s me, it’s us (…) usually me and the nurse (…)’ (male, 58 years) | |||

| Written information about tuberculosis to give to the patient | ‘No (…) we had phases in which we had brochures and gave them to everyone, now we are in a phase of reevaluating what is written (…)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Perceptions about the process of monitoring incarcerated patients | Diagnosis | ‘(…) the diagnosis is usually made when they are already in a very advanced situation (…) because they are not patients who easily comply with rules, nor do they adjust, they wait a long time and until they have symptoms and really already sick people come to ask for help.’ (female, 43 years) | ||

| Prevention | ‘(…) The problem appears later when they are better, because then we have more problems so that they continue to do things in a regulated way and then have follow-up (…) and prevention is obviously always difficult, because they feel good and therefore do not see the need to do anything else.’ (female, 43 years) |

Themes, subthemes and categories of thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews

| Theme . | Sub-theme . | Category . | Theme definition . | Citations examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Perceptions about the protocol | Perceptions about the usefulness of the protocol | This topic aims to understand the participants’ level of knowledge about the protocol and its usefulness | ‘The protocol aims to ensure that there are no outbreaks of tuberculosis in prisons (...)’ (female, 45 years old) | |

| Perceptions about protocol knowledge | ‘Protocol no, I don’t know (...) I don’t know about this protocol (...) Does it exist, by the way?’ (male, 57 years old) | |||

| Insights into the protocol domain | ‘(...) to perceive if the patient is ill or not, by doing an initial screening for the disease. And then repeat this screening every year to make sure there are no new cases of tuberculosis. In other words, screening on entry and then, in theory, annually, according to the profile of the cases. There is also the possibility of screening for latent tuberculosis, but the disease is the priority in this regard.’ (female, 45 years old) | |||

| 2) Articulation between TB outpatient center and prison establishment | Appreciation of articulation and factors influencing articulation | This theme aims to understand the participant’s relationship with the PE with whom they articulate and what factors influence this relationship | ‘(...) difficult... difficult to communicate (...) there is a lack of communication, whenever there is a request for information, there is usually little feedback. Whenever problems are detected and we try to clarify and help resolve them, we can’t get through (...)’ (female, 47 years old) | |

| Relationship with PE-health professionals | Procedures | ‘(...) I always spoke to my colleague (...) always to the same person... it always went very well. We quickly realised what each other wanted and... everything went very smoothly. It’s a good relationship, I’ve never had any difficulties (...) friendly, respectful, and from a professional point of view, really professional, always trying to solve the problems we had, both on my part and on my colleague’s part (...) It was always the same” (male, 54 years old) | ||

| Perceptions about the inter-institutional articulation between PE and PDC | Evolution of the articulation | ‘The first contact I use is always the cell phone (…) either via WhatsApp (…) if I can’t reach them, it will be via email’ (female, 65 years old) | ||

| 3) Diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis | Contact tracing | This theme aims to understand the process of diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis, from entry into the PE to the exit from the PE, in which institutions are involved, and the appreciation of the articulation between these | ‘Not in a situation of imprisonment’ ou ‘not during detention/imprisonment’ (male, 58 years) | |

| Perceptions about the liberation process and/or transfer of a prisoner with tuberculosis | ‘(...) one of the problems is the lack of human resources (...) we’re increasingly trying to get colleagues out into the field, internal colleagues and even other professionals, because we need to. We have to mobilise more human resources and not just doctors, because nurses play a fundamental role here...in records and assessments and even in talking to patients (...)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Education of the inmate or ex-prisoner patient | Perception of the level of literacy about tuberculosis before the first consultation at the PDC | ‘(...) Neither prisoners nor non-prisoners! People aren’t educated about anything! (...) They have no knowledge about the disease (...) the dangers they face(...)’ (male, 58 years) | ||

| Patient education at PDC | ‘It’s me, it’s us (…) usually me and the nurse (…)’ (male, 58 years) | |||

| Written information about tuberculosis to give to the patient | ‘No (…) we had phases in which we had brochures and gave them to everyone, now we are in a phase of reevaluating what is written (…)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Perceptions about the process of monitoring incarcerated patients | Diagnosis | ‘(…) the diagnosis is usually made when they are already in a very advanced situation (…) because they are not patients who easily comply with rules, nor do they adjust, they wait a long time and until they have symptoms and really already sick people come to ask for help.’ (female, 43 years) | ||

| Prevention | ‘(…) The problem appears later when they are better, because then we have more problems so that they continue to do things in a regulated way and then have follow-up (…) and prevention is obviously always difficult, because they feel good and therefore do not see the need to do anything else.’ (female, 43 years) |

| Theme . | Sub-theme . | Category . | Theme definition . | Citations examples . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Perceptions about the protocol | Perceptions about the usefulness of the protocol | This topic aims to understand the participants’ level of knowledge about the protocol and its usefulness | ‘The protocol aims to ensure that there are no outbreaks of tuberculosis in prisons (...)’ (female, 45 years old) | |

| Perceptions about protocol knowledge | ‘Protocol no, I don’t know (...) I don’t know about this protocol (...) Does it exist, by the way?’ (male, 57 years old) | |||

| Insights into the protocol domain | ‘(...) to perceive if the patient is ill or not, by doing an initial screening for the disease. And then repeat this screening every year to make sure there are no new cases of tuberculosis. In other words, screening on entry and then, in theory, annually, according to the profile of the cases. There is also the possibility of screening for latent tuberculosis, but the disease is the priority in this regard.’ (female, 45 years old) | |||

| 2) Articulation between TB outpatient center and prison establishment | Appreciation of articulation and factors influencing articulation | This theme aims to understand the participant’s relationship with the PE with whom they articulate and what factors influence this relationship | ‘(...) difficult... difficult to communicate (...) there is a lack of communication, whenever there is a request for information, there is usually little feedback. Whenever problems are detected and we try to clarify and help resolve them, we can’t get through (...)’ (female, 47 years old) | |

| Relationship with PE-health professionals | Procedures | ‘(...) I always spoke to my colleague (...) always to the same person... it always went very well. We quickly realised what each other wanted and... everything went very smoothly. It’s a good relationship, I’ve never had any difficulties (...) friendly, respectful, and from a professional point of view, really professional, always trying to solve the problems we had, both on my part and on my colleague’s part (...) It was always the same” (male, 54 years old) | ||

| Perceptions about the inter-institutional articulation between PE and PDC | Evolution of the articulation | ‘The first contact I use is always the cell phone (…) either via WhatsApp (…) if I can’t reach them, it will be via email’ (female, 65 years old) | ||

| 3) Diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis | Contact tracing | This theme aims to understand the process of diagnosis and monitoring of patients with tuberculosis, from entry into the PE to the exit from the PE, in which institutions are involved, and the appreciation of the articulation between these | ‘Not in a situation of imprisonment’ ou ‘not during detention/imprisonment’ (male, 58 years) | |

| Perceptions about the liberation process and/or transfer of a prisoner with tuberculosis | ‘(...) one of the problems is the lack of human resources (...) we’re increasingly trying to get colleagues out into the field, internal colleagues and even other professionals, because we need to. We have to mobilise more human resources and not just doctors, because nurses play a fundamental role here...in records and assessments and even in talking to patients (...)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Education of the inmate or ex-prisoner patient | Perception of the level of literacy about tuberculosis before the first consultation at the PDC | ‘(...) Neither prisoners nor non-prisoners! People aren’t educated about anything! (...) They have no knowledge about the disease (...) the dangers they face(...)’ (male, 58 years) | ||

| Patient education at PDC | ‘It’s me, it’s us (…) usually me and the nurse (…)’ (male, 58 years) | |||

| Written information about tuberculosis to give to the patient | ‘No (…) we had phases in which we had brochures and gave them to everyone, now we are in a phase of reevaluating what is written (…)’ (female, 65 years) | |||

| Perceptions about the process of monitoring incarcerated patients | Diagnosis | ‘(…) the diagnosis is usually made when they are already in a very advanced situation (…) because they are not patients who easily comply with rules, nor do they adjust, they wait a long time and until they have symptoms and really already sick people come to ask for help.’ (female, 43 years) | ||

| Prevention | ‘(…) The problem appears later when they are better, because then we have more problems so that they continue to do things in a regulated way and then have follow-up (…) and prevention is obviously always difficult, because they feel good and therefore do not see the need to do anything else.’ (female, 43 years) |

Perceptions about the protocol

Participants’ opinions on the protocol varied based on its perceived usefulness, knowledge and expertise. Approximately 42.8% noted that the protocol enhanced coordination between the TB outpatient center and PE by standardizing diagnostic, treatment and follow-up procedures for incarcerated patients.

‘(…) There was an effort to standardize procedures in prison establishments and set some rules for coordination with the TB Outpatient Centers. (…) I see positive aspects indeed, especially in the relationship with the TB Outpatient Centers... in terms of support at contact tracing and in some cases even support in treatment... and in the follow-up and treatment of patients (...)’ (male, 63 years).

Thirty-eight percent of participants were unaware of the protocol. Some had never received incarcerated patients and deemed it unnecessary to read, while others relied on different entities for coordination between the TB outpatient center and PE, or were simply unaware of its existence.

‘No, no (…) we do not articulate with the prison establishment (…) it is through Public Health professionals that we know about the patient’ (male, 58 years).

From the total, 19% described procedures included in the protocol. The most frequently mentioned procedures were related to screening upon entry into the PE and periodic screening.

‘(...) this protocol... allows for screening at the entrance of the prison, for any individual who enters the prison environment... with mandatory registration, with an inquiry... with x days to be carried out, with a chest x-ray, a tuberculin skin test, sputum examination, therefore clinical investigation (…)’ (female, 65 years).

Perceptions about the articulation between TB outpatient center and prison establishment

The participants described that over time, there has been a positive evolution in the coordination with the PE in diagnosing and monitoring the incarcerated patient, in which communication has been mainly improved.

‘It is a collaboration that is becoming increasingly simplified via digital information. When we didn’t have the possibility to see so much progress in terms of information technology, both in scheduling screenings and appointments, and in the post-reading evaluation of X-rays, everything was more difficult because sometimes articulating with the prison establishment via telephone was very challenging (…). We have everything now, we know who the people are, we are familiar with the people (…). We have telephone contacts, we have email contacts, contact is easy (…).’ (female, 65 years).

Communication was mentioned several times throughout the participants’ speech and was considered the key element in articulating the two entities. However, opinions differed on how it was established: some described it with a positive connotation, others with a negative connotation.

‘This has varied over time. There was a time when in fact contact was very difficult (...) Now there is an interlocutor (...) there are people with... when there are doubts, when there are problems with whom we can communicate’ (female, 65 years).

Another element considered important by the participants for easier coordination between PEs is the fact that they know the PE professionals with whom they articulate:

‘(…) good. Whether it’s through written information or through phone contact (…), there’s always an easy dialogue (…) but it’s also related to the fact with the professional acquaintanceship we share... among ourselves’ (male, 66 years).

Letters and telephones were the two most used means of communication—14.3% of participants mentioned that they also used other means, namely fax, email and WhatsApp.

‘Sometimes there is telephone contact from the prison doctor (…) I think that hasn’t always happened. (…) Perhaps other colleagues here, who work more days, come more often, maybe they receive more phone calls. I receive a call from my colleague in prison... but I’m not sure if it’s always... I believe that in one or two cases, it didn’t happen... the patient already came with a letter’ (male, 57 years).

Diagnosis and monitoring of incarcerated patients with tuberculosis

Concerning the flow of clinical information for incarcerated patients in both diagnostic and treatment contexts before and after incarceration, over half of the participants reported receiving and sending the patient’s clinical information to the PE when requested.

‘(…) Yes, in general, I receive it (…) the prison doctor (…)’ (male, 57 years).

Concerning contact tracing in prison, 33.3% reported it is not conducted in their TB outpatient center, either due to the absence of prison patients or because it falls under the PE’s responsibility. Sixty-six-point seven per cent reported conducting contact tracing at the TB outpatient center.

‘(…) I support contact tracing 100% (…) I’ve already done some’ (female, 65 years).

‘To the family (…) that’s up to the doctor there’ (male, 65 years).

When asked whether there were difficulties in operationalizing it, there was a difference of opinion: more than half considered that there were no constraints. However, constraints were mentioned, including the lack of human resources.

‘(…) The screening is in a protocol (…) already pre-established, already accepted by several entities, and it’s easy, you just have to follow the protocol, right?’ (male, 57 years).

Regarding participants’ views on PDL or ex-prisoners’ knowledge of TB, the majority (85.7%) indicated no prior awareness of the disease. Only 14.3% reported that some individuals came to the consultation with some knowledge about TB transmission and prevention.

‘Yes, yes (…) They are already instructed on the procedures, on the risks of transmitting the disease’ (male, 66 years).

‘Health literacy is something we fail at the national level (…) And much less about tuberculosis (…) There has been a growing concern (…) in prisons this information (…) I think Portuguese society has little information (…) no (…) they are not informed (…).’ (female, 65 years).

All participants affirmed that TB education is offered at TB outpatient centers. They conveyed information on transmission modes, signs, symptoms, mask usage and stressed the importance of direct observation. Participants consistently emphasized the active role of nurses in patient education.

‘(…) Of course! (…) It’s more the nurse. We do it, but it’s a task that nurses do more (…)’ (male, 57 years).

In some TB outpatient centers, there is written information about the disease available to give to the patient, including the symptoms of the disease, modes of transmission and preventive measures for transmission; although this, some centers do not have written material available.

‘There is a little pamphlet there. It was done by one of the nurses (…) It is information about what the disease is like, how people get tuberculosis, what it is, what the main symptoms are (…) when you should go to the doctor, what are the consequences that could occur if you don’t treat them, the possible treatment (...).’ (male, 57 years).

When queried about challenges related to diagnosis, treatment or disease prevention, most participants indicated they did not encounter significant obstacles. Specifically, regarding treatment, participants expressed difficulty sustaining a patient’s therapy post-symptomatic improvement.

‘(…) and prevention is obviously always difficult, because they feel well and, therefore, they don’t see the need to do anything else’ (female, 43 years).

Another mentioned challenge pertained to delays and/or errors in the diagnostic methods. Some participants underscored delays in obtaining results from analytical studies, noting instances of incorrect or incomplete submissions.

‘(…) In treatment, sometimes there are problems when we are carrying out surveillance (…) during treatment, the analytical study sometimes does not come on time or does not come with what we ask for to be collected (…)’ (female, 43 years).

Regarding diagnosis, professionals highlighted that the challenges primarily stemmed from patients seeking health services at an advanced stage of symptoms.

Public health implications derived from the interviews

A set of public health implications derived from the thematic analysis can be found in Table 2.

| Protocol awareness and utilization | Positive impact: the perception that the protocol has improved coordination and standardization of procedures for incarcerated patients is a positive outcome. This suggests that a standardized approach can enhance the management of TB within prison settings |

| Gap in knowledge: the significant portion of specialists unaware of the protocol raises concerns. Addressing this gap in awareness is crucial for ensuring consistent implementation and adherence to established procedures | |

| Communication and coordination | Positive evolution: the positive evolution in communication and coordination between TB outpatient centers and prisons is a promising trend. Improved communication, facilitated by technology, enhances the efficiency of TB diagnosis and monitoring within prison settings |

| Differing opinions: varied opinions on the establishment of communication suggest that there may be challenges in maintaining consistent and effective channels. Addressing these variations is essential for seamless coordination | |

| Diagnosis and monitoring | Information flow: the successful exchange of clinical information between institutions is a positive aspect, contributing to effective diagnosis and treatment. However, challenges in contact tracing and resource constraints indicate potential areas for improvement |

| Health literacy: the low level of knowledge about TB among inmates emphasizes the need for targeted educational initiatives. Enhancing health literacy within prison populations can contribute to prevention and early intervention | |

| Patient education | Nurse involvement: the active role of nurses in patient education is noteworthy. Leveraging this involvement and ensuring consistency in educational practices can strengthen efforts to inform and empower inmates about TB |

| Challenges in health literacy: the challenges in health literacy at both the national and prison levels underscore the importance of comprehensive education campaigns to address misconceptions and gaps in understanding |

| Protocol awareness and utilization | Positive impact: the perception that the protocol has improved coordination and standardization of procedures for incarcerated patients is a positive outcome. This suggests that a standardized approach can enhance the management of TB within prison settings |

| Gap in knowledge: the significant portion of specialists unaware of the protocol raises concerns. Addressing this gap in awareness is crucial for ensuring consistent implementation and adherence to established procedures | |

| Communication and coordination | Positive evolution: the positive evolution in communication and coordination between TB outpatient centers and prisons is a promising trend. Improved communication, facilitated by technology, enhances the efficiency of TB diagnosis and monitoring within prison settings |

| Differing opinions: varied opinions on the establishment of communication suggest that there may be challenges in maintaining consistent and effective channels. Addressing these variations is essential for seamless coordination | |

| Diagnosis and monitoring | Information flow: the successful exchange of clinical information between institutions is a positive aspect, contributing to effective diagnosis and treatment. However, challenges in contact tracing and resource constraints indicate potential areas for improvement |

| Health literacy: the low level of knowledge about TB among inmates emphasizes the need for targeted educational initiatives. Enhancing health literacy within prison populations can contribute to prevention and early intervention | |

| Patient education | Nurse involvement: the active role of nurses in patient education is noteworthy. Leveraging this involvement and ensuring consistency in educational practices can strengthen efforts to inform and empower inmates about TB |

| Challenges in health literacy: the challenges in health literacy at both the national and prison levels underscore the importance of comprehensive education campaigns to address misconceptions and gaps in understanding |

| Protocol awareness and utilization | Positive impact: the perception that the protocol has improved coordination and standardization of procedures for incarcerated patients is a positive outcome. This suggests that a standardized approach can enhance the management of TB within prison settings |

| Gap in knowledge: the significant portion of specialists unaware of the protocol raises concerns. Addressing this gap in awareness is crucial for ensuring consistent implementation and adherence to established procedures | |

| Communication and coordination | Positive evolution: the positive evolution in communication and coordination between TB outpatient centers and prisons is a promising trend. Improved communication, facilitated by technology, enhances the efficiency of TB diagnosis and monitoring within prison settings |

| Differing opinions: varied opinions on the establishment of communication suggest that there may be challenges in maintaining consistent and effective channels. Addressing these variations is essential for seamless coordination | |

| Diagnosis and monitoring | Information flow: the successful exchange of clinical information between institutions is a positive aspect, contributing to effective diagnosis and treatment. However, challenges in contact tracing and resource constraints indicate potential areas for improvement |

| Health literacy: the low level of knowledge about TB among inmates emphasizes the need for targeted educational initiatives. Enhancing health literacy within prison populations can contribute to prevention and early intervention | |

| Patient education | Nurse involvement: the active role of nurses in patient education is noteworthy. Leveraging this involvement and ensuring consistency in educational practices can strengthen efforts to inform and empower inmates about TB |

| Challenges in health literacy: the challenges in health literacy at both the national and prison levels underscore the importance of comprehensive education campaigns to address misconceptions and gaps in understanding |

| Protocol awareness and utilization | Positive impact: the perception that the protocol has improved coordination and standardization of procedures for incarcerated patients is a positive outcome. This suggests that a standardized approach can enhance the management of TB within prison settings |

| Gap in knowledge: the significant portion of specialists unaware of the protocol raises concerns. Addressing this gap in awareness is crucial for ensuring consistent implementation and adherence to established procedures | |

| Communication and coordination | Positive evolution: the positive evolution in communication and coordination between TB outpatient centers and prisons is a promising trend. Improved communication, facilitated by technology, enhances the efficiency of TB diagnosis and monitoring within prison settings |

| Differing opinions: varied opinions on the establishment of communication suggest that there may be challenges in maintaining consistent and effective channels. Addressing these variations is essential for seamless coordination | |

| Diagnosis and monitoring | Information flow: the successful exchange of clinical information between institutions is a positive aspect, contributing to effective diagnosis and treatment. However, challenges in contact tracing and resource constraints indicate potential areas for improvement |

| Health literacy: the low level of knowledge about TB among inmates emphasizes the need for targeted educational initiatives. Enhancing health literacy within prison populations can contribute to prevention and early intervention | |

| Patient education | Nurse involvement: the active role of nurses in patient education is noteworthy. Leveraging this involvement and ensuring consistency in educational practices can strengthen efforts to inform and empower inmates about TB |

| Challenges in health literacy: the challenges in health literacy at both the national and prison levels underscore the importance of comprehensive education campaigns to address misconceptions and gaps in understanding |

Discussion

Main finding of this study

We sought medical doctors’ perspectives on the coordination between Prison establishments and TB outpatient centers. Most participants found the protocol applicable, highlighting its role in enhancing coordination by standardizing and documenting diagnosis, treatment and follow-up procedures for PDL patients. We found that many doctors were unaware of the protocol, either due to not receiving inmates at their center or because of lacking knowledge on its existence. Among those claiming awareness, limited knowledge was evident, primarily focused on entry and periodic screening procedures, reflected in their non-verbal cues, showing nervousness during responses.

What is already known on this topic

In recent years, the National Program for Tuberculosis has made efforts to improve healthcare services by defining best clinical practices, training healthcare professionals and enhancing access to healthcare through coordinated protocols with other entities working with vulnerable populations, including the DGRSP. These measures have contributed to a reduction in TB incidence in the country.18 However, it was evident from the interviews that some professionals in this field remain unaware of official protocols, potentially impeding the coordination of patient clinical monitoring among relevant stakeholders. This underscores the importance of continued investments in training, qualification and multidisciplinary coordination to maintain the progress achieved thus far.27

What this study adds

Regarding the coordination between the Prison Health Directorate and PEs in diagnosing and monitoring incarcerated patients, participants reported that it has improved, particularly in communication. However, their responses hinted at lingering weaknesses. The absence of seamless collaboration between these entities can lead to fragmented care, resulting in less favorable treatment outcomes and disease prevention. As part of public health (2003), the Moscow Declaration on Prison Health recommended that public health services and prisons collaborate to ensure early detection, immediate and appropriate treatment and prevention of disease transmission within prisons.18 Therefore, it is evident that addressing the remaining weaknesses in the coordination between these two entities is essential.27

Participants also noted that TB literacy among PDL patients is generally low. Studies in other countries have found a positive correlation between TB knowledge, seeking medical care, and treatment adherence.28 Enhancing health literacy in this at-risk population contributes to early tuberculosis diagnosis.28 Thus, investing in health education for this population is deemed important.

Approximately 42.8% of participants in our study recognized the positive impact of a protocol aimed at improving coordination between TB outpatient centers and prisons. This protocol plays a crucial role in standardizing diagnostic and treatment procedures for incarcerated patients. This finding aligns with the guidelines set forth by the WHO Regional Office for Europe in 2014.29 According to these guidelines, healthcare providers in prison are not only encouraged but obligated to collaborate and communicate effectively to engage incarcerated patients. The WHO emphasizes the state’s special duty of care for individuals in places of detention, emphasizing the equivalence of healthcare services within prisons to those in the community.30 The duty of care remains unwavering for professional staff, regardless of whether the patient is in prison or at liberty. Furthermore, the importance of continuity of care is highlighted for a sustainable prison health service, extending services beyond release into the community. To achieve comprehensive healthcare for incarcerated individuals, the WHO advocates for the integration of prison health services into regional and national health systems, aligning with the principles revealed by our study participants.

In the prison setting, communication and coordination are more intricate than in the community. Healthcare providers must not only coordinate with each other and social services for various health conditions but also engage with security and other prison staff.31 Effective multidisciplinary collaboration between prison staff and health professionals is vital to timely information sharing between teams. This efficient communication is crucial for delivering non-fragmented healthcare to patients with complex needs, ensuring continuity from entry to transfers, referrals and release into the community.31

Public health implications: challenges and strategies for the future

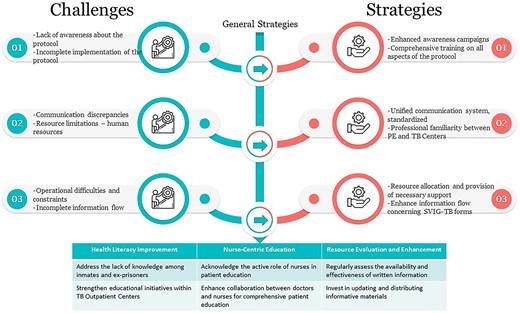

Based on all the challenges highlighted, we proposed as general and urgent strategies for the future (Fig. 1) health literacy improvement for both health professionals and inmates, nurse-centric education since they represent a bigger part of patient education and resource evaluation and enhancement to improve informative materials, that are not broadly available.

Public health implications derived from the interviews: challenges and strategies.

Develop strategies for disseminating information to understand standardized procedures and establish clear guidelines for communication channels between TB outpatient centers and prisons are of major importance to ensure consistency. Also, the implementation of training to familiarize professionals with effective communication methods should be periodized. More importantly, the launch of educational campaigns within prisons to improve health literacy among inmates concerning all health problems and especially infectious diseases can equip them with the necessary tools to identify health alterations. Moreover, there is a need to address resource constraints, especially in diagnostic methods and treatment sustainment, to ensure timely availability of analytical results and implement strategies to overcome challenges in sustaining therapy post-symptomatic improvement.

These actions aim to address the identified challenges and capitalize on positive outcomes, fostering an environment that prioritizes effective communication, standardized procedures and comprehensive education for both healthcare professionals and incarcerated individuals.

Limitations

This study has limitations that need consideration. Firstly, the findings’ generalizability is constrained as the study is specific to certain districts in Portugal, potentially limiting applicability to regions or countries with distinct healthcare systems and prison settings. However, the metropolitan areas of Porto and Lisbon are where the highest incidence and prevalence of tuberculosis occur in Portugal. Additionally, data collection was conducted between May and June 2018, the study might not fully capture subsequent changes in healthcare or prison settings, though the highlighted difficulties persist according to ongoing observations. Self-reporting bias is also possible, as participants may provide socially desirable responses or withhold knowledge about the protocol. Lastly, the study primarily reflects healthcare professionals’ perspectives, lacking insights from incarcerated patients, limiting a comprehensive understanding of challenges in TB detection and treatment within prison settings.

Strengths

Despite certain limitations, the study boasts several strengths. First, it offers participant diversity, including specialist doctors from various districts, and ensures varied perspectives. The commitment to interviewing as many doctors as feasible demonstrates dedication to capturing a comprehensive understanding, achieving theoretical data saturation in qualitative analysis. Additionally, the use of semi-structured interviews and a well-informed script ensures a systematic approach to data collection. The inclusion of participant characteristics, addressing various TB diagnoses and monitoring aspects enriches the dataset.

Conclusion

The study offers valuable insights into specialist doctors’ experiences and perspectives on tuberculosis detection in prisons. The findings highlight the significance of effective communication, protocol awareness, and addressing diagnostic and monitoring challenges. There is a clear need for further research and interventions to improve collaboration, knowledge dissemination and overall effectiveness in tuberculosis detection within prison environments.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. through the projects with references UIDB/04750/2020 and LA/P/0064/2020 and DOI identifiers https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04750/2020 and https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0064/2020. The corresponding author, A.A., received support through her PhD Grant (reference: 2020.09390.BD; https://doi.org/10.54499/2020.09390.BD), co-funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia and the Fundo Social Europeu Program. The funders played no role in the design, data collection and analysis, publication decision or manuscript preparation of the study.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Author contributions

AA, MA and RD developed the basic research questions and study methodology. MA was responsible for data analysis. All authors were involved in data interpretation. AA wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript and approved it.

Data availability

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author (ana.aguiar@ispup.up.pt).

Ana Aguiar, PhD Student, Researcher

Mariana Abreu, Medical Doctor

Raquel Duarte, Invited Associate Professor with Aggregation, Researcher, Medical Doctor

References

Harries AD, Kumar AMV, Satyanarayana S. et al. . The Growing Importance of Tuberculosis Preventive Therapy and How Research and Innovation Can Enhance Its Implementation on the Ground.

Author notes

Ana Aguiar and Mariana Abreu contributors and first authorship.