-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yoichiro Tohi, Takuma Kato, Jimpei Miyakawa, Ryuji Matsumoto, Hiroshi Sasaki, Koji Mitsuzuka, Junichi Inokuchi, Masafumi Matsumura, Akira Yokomizo, Hidefumi Kinoshita, Isao Hara, Norihiko Kawamura, Kohei Hashimoto, Masaharu Inoue, Jun Teishima, Hidenori Kanno, Hiroshi Fukuhara, Satoru Maruyama, Shinichi Sakamoto, Toshihiro Saito, Yoshiyuki Kakehi, Mikio Sugimoto, Impact of adherence to criteria on oncological outcomes of radical prostatectomy in patients opting for active surveillance: data from the PRIAS-JAPAN study, Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, Volume 52, Issue 9, September 2022, Pages 1056–1061, https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyac092

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate whether oncological outcomes of radical prostatectomy differ depending on adherence to the criteria in patients who opt for active surveillance.

We retrospectively reviewed the data of 1035 patients enrolled in a prospective cohort of the PRIAS-JAPAN study. After applying the exclusion criteria, 136 of 162 patients were analyzed. Triggers for radical prostatectomy due to pathological reclassification on repeat biopsy were defined as on-criteria. Off-criteria triggers were defined as those other than on-criteria triggers. Unfavorable pathology on radical prostatectomy was defined as pathological ≥T3, ≥GS 4 + 3 and pathological N positivity. We compared the pathological findings on radical prostatectomy and prostate-specific antigen recurrence-free survival between the two groups. The off-criteria group included 35 patients (25.7%), half of whom received radical prostatectomy within 35 months.

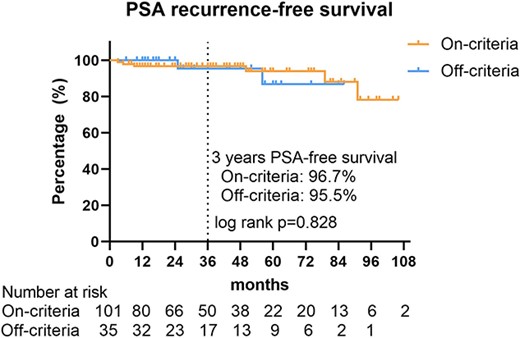

There were significant differences in median prostate-specific antigen before radical prostatectomy between the on-criteria and off-criteria groups (6.1 vs. 8.3 ng/ml, P = 0.007). The percentage of unfavorable pathologies on radical prostatectomy was lower in the off-criteria group than that in the on-criteria group (40.6 vs. 31.4%); however, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.421). No significant difference in prostate-specific antigen recurrence-free survival was observed between the groups during the postoperative follow-up period (median: 36 months) (log-rank P = 0.828).

Half of the off-criteria patients underwent radical prostatectomy within 3 years of beginning active surveillance, and their pathological findings were not worse than those of the on-criteria patients.

Introduction

Active surveillance (AS) is the standard of care for early-stage prostate cancer (PC) (1,2), with an increase in its treatment selection rate (3,4). AS is employed as a strategy to postpone the curative treatment for patients with early-stage PC while monitoring their disease status. AS aim to minimize the adverse effects of unnecessary invasive definitive treatments while maintaining patient survival.

The triggers for the definitive treatment of AS are strictly criteria-based with respect to every protocol globally (5–7); however, some patients may be surgically treated without adherence to the criteria (on- or off-criteria), which are the pathological reclassifications on repeat prostate biopsy (8,9). A previous study has investigated the definitive treatment after AS discontinuation using data from Prostate Cancer Research International: Active Surveillance (PRIAS), a large global prospective cohort study (8). In their study, 52 and 73% of patients discontinued AS at 5 and 10 years of follow-up, respectively. In 37% of patients who discontinued AS, radical prostatectomy (RP) was performed as the definitive treatment, and the off-criteria was the reason for RP in 24.4% (8), thus contributing to overtreatment of low-risk PC. However, patient anxiety is a justifiable reason for performing RP, and overtreatment may lead to adverse postoperative complications.

Although there have been some reports on the outcome of RP in patients who opted for AS (9–13), the outcomes of RP after AS, which are stratified by adherence to the criteria for definitive treatment, have not been well evaluated. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate whether pathological and oncological outcomes differ depending on adherence to the criteria in patients who opted for AS using the data from a multi-institutional prospective observational cohort in the PRIAS-JAPAN study.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

PRIAS-JAPAN is a prospective, multi-institutional, cohort study for early-stage PC, the Japanese cohort of PRIAS (14). Informed consent was obtained at the time of enrollment in the PRIAS study. The detailed data collection methods, inclusion criteria and follow-up protocol for PRIAS-JAPAN have been reported earlier (9,15). The criteria for inclusion in the PRIAS study were a Gleason score (GS) of ≤3 + 3 or 3 + 4 (≤10% cancer involvement if aged ≥70 years) at the diagnostic biopsy, a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) of ≤10 ng/ml, a PSA density of <0.2 ng/ml/cc, a T stage of ≤cT2 and ≤2 cores positive for PC. Regular PSA measurement, digital rectal examination and repeat biopsy were performed. Repeat biopsies were recommended at 1, 4, 7 and 10 years and every 5 years thereafter.

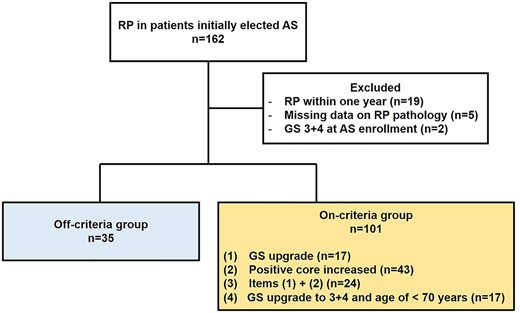

We retrospectively reviewed the data of 1035 patients enrolled in a prospective cohort of the PRIAS-JAPAN study between January 2010 and September 2020. Furthermore, patients who underwent RP after enrollment in the PRIAS-JAPAN study were included in this study. Of these, patients with GS 3 + 4 at diagnosis and RP within a year of enrollment were excluded. The following triggers for RP due to pathological reclassification on repeat biopsy were defined as on-criteria: (i) GS upgrade, (ii) positive core increased, (iii) items (1) + (2) or (iv) a GS upgrade to 3 + 4 and age of <70 years (9). Off-criteria triggers were defined as those other than on-criteria triggers.

Statistical analysis

Patients who underwent RP were divided into two groups depending on adherence to the criteria: the on-criteria and off-criteria groups.

The primary endpoints were the comparison of pathological findings (unfavorable pathology and resection margin) on RP between the on-criteria and off-criteria groups. Unfavorable pathology was defined as pathological ≥T3, GS ≥4 + 3, extraprostatic extension positivity, seminal vesicle invasion and pathological N positivity. The secondary endpoint was the evaluation of PSA recurrence-free survival. We compared PSA recurrence-free survival after RP of the on- and off-criteria groups. PSA recurrence after RP was defined as a PSA level of >0.2 ng/ml.

Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables were performed to compare both groups. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to examine intergroup association. Logistic regression analyses results were presented as odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to evaluate the time-to-event, and a log-rank test was used to estimate the difference. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 25.0., IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kagawa University (admission number: 2021-137). This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The need for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study; however, information regarding this study was disclosed on the website, where patients were offered the opportunity to refuse inclusion in the study.

Results

Overall, 1035 patients were prospectively enrolled into the PRIAS-JAPAN cohort during the study period. A total of 136 patients who subsequently underwent RP were analyzed, excluding two patients with GS 3 + 4 at diagnosis, 19 patients who underwent RP within a year of enrollment and five patients with missing data on RP pathology (Fig. 1). Of these, 35 patients (25.7%) were off-criteria. The median time to RP among off-criteria patients was 35 months (Table 1). The on-criteria group was defined as follows: (i) GS upgrade, 17 patients (17%); (ii) positive core increased, 43 patients (43%); (iii) items (1) + (2), 24 patients (24%) and (iv) GS upgrade to 3 + 4 and age of <70 years, 17 patients (17%) (Fig. 1).

Flow diagram of this study. RP, radical prostatectomy; AS, active surveillance; GS, Gleason score.

| . | Total . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 | 101 | 35 | |

| Median age at AS enrollment, year (IQR) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (60–70) | 0.643 |

| Median PSA at AS enrollment, ng/ml (IQR) | 5.23 (4.43–6.73) | 5.22 (4.4–6.64) | 5.37 (4.7–7.2) | 0.522 |

| Median PSA density at AS enrollment, ng/ml/cc (IQR) | 0.16 (0.12–0.19) | 0.15 (0.12–0.19) | 0.16 (0.11–0.19) | 0.99 |

| Median prostate volume at AS enrollment, cc (IQR) | 36.5 (28.6–48.5) | 36.3 (28.6–48.8) | 39.1 (28–48.6) | 0.803 |

| MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | 84 (61.8) | 60 (59.4) | 24 (68.6) | 0.68 |

| PIRADS on MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | ||||

| ≤2 | 37 (44) | 24 (40) | 13 (54.2) | 0.422 |

| 3 | 15 (17.9) | 12 (20) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 4 | 17 (20.2) | 12 (20) | 5 (20.8) | |

| 5 | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Missing | 12 (14.3) | 11 (18.3) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Median time to RP, months (IQR) | 20 (15–47.8) | 16 (14–43) | 35 (15–45.5) | <0.001 |

| Median age at RP, year (IQR) | 68 (63–73) | 68.2 (63.3–73.3) | 68.9 (63.5–72.5) | 0.805 |

| Median PSA before RP, n (%) | 6.55 (4.8–8.9) | 6.1 (4.7–8.4) | 8.3 (5–11.3) | 0.007 |

| Median PSA doubling time before RP, month (IQR) | 2.2 (−2.2–3.9) | 2.2 (−2.6–3.8) | 2.1 (1.0–4.4) | 0.681 |

| Prostatectomy procedure, n (%) | ||||

| Robot-assisted | 111 (81.6) | 82 (90) | 29 (82.4) | 0.69 |

| Laparoscopic | 13 (9.6) | 9 (10) | 4 (9.2) | |

| Open | 12 (8.8) | 10 (0) | 2 (8.4) |

| . | Total . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 | 101 | 35 | |

| Median age at AS enrollment, year (IQR) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (60–70) | 0.643 |

| Median PSA at AS enrollment, ng/ml (IQR) | 5.23 (4.43–6.73) | 5.22 (4.4–6.64) | 5.37 (4.7–7.2) | 0.522 |

| Median PSA density at AS enrollment, ng/ml/cc (IQR) | 0.16 (0.12–0.19) | 0.15 (0.12–0.19) | 0.16 (0.11–0.19) | 0.99 |

| Median prostate volume at AS enrollment, cc (IQR) | 36.5 (28.6–48.5) | 36.3 (28.6–48.8) | 39.1 (28–48.6) | 0.803 |

| MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | 84 (61.8) | 60 (59.4) | 24 (68.6) | 0.68 |

| PIRADS on MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | ||||

| ≤2 | 37 (44) | 24 (40) | 13 (54.2) | 0.422 |

| 3 | 15 (17.9) | 12 (20) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 4 | 17 (20.2) | 12 (20) | 5 (20.8) | |

| 5 | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Missing | 12 (14.3) | 11 (18.3) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Median time to RP, months (IQR) | 20 (15–47.8) | 16 (14–43) | 35 (15–45.5) | <0.001 |

| Median age at RP, year (IQR) | 68 (63–73) | 68.2 (63.3–73.3) | 68.9 (63.5–72.5) | 0.805 |

| Median PSA before RP, n (%) | 6.55 (4.8–8.9) | 6.1 (4.7–8.4) | 8.3 (5–11.3) | 0.007 |

| Median PSA doubling time before RP, month (IQR) | 2.2 (−2.2–3.9) | 2.2 (−2.6–3.8) | 2.1 (1.0–4.4) | 0.681 |

| Prostatectomy procedure, n (%) | ||||

| Robot-assisted | 111 (81.6) | 82 (90) | 29 (82.4) | 0.69 |

| Laparoscopic | 13 (9.6) | 9 (10) | 4 (9.2) | |

| Open | 12 (8.8) | 10 (0) | 2 (8.4) |

IQR, interquartile range; AS, acive surveillance; PSA, prostate specific antigen; PIRADS, Prostate Imaging Reporting And Data System; RP, radical prostatectomy.

| . | Total . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 | 101 | 35 | |

| Median age at AS enrollment, year (IQR) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (60–70) | 0.643 |

| Median PSA at AS enrollment, ng/ml (IQR) | 5.23 (4.43–6.73) | 5.22 (4.4–6.64) | 5.37 (4.7–7.2) | 0.522 |

| Median PSA density at AS enrollment, ng/ml/cc (IQR) | 0.16 (0.12–0.19) | 0.15 (0.12–0.19) | 0.16 (0.11–0.19) | 0.99 |

| Median prostate volume at AS enrollment, cc (IQR) | 36.5 (28.6–48.5) | 36.3 (28.6–48.8) | 39.1 (28–48.6) | 0.803 |

| MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | 84 (61.8) | 60 (59.4) | 24 (68.6) | 0.68 |

| PIRADS on MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | ||||

| ≤2 | 37 (44) | 24 (40) | 13 (54.2) | 0.422 |

| 3 | 15 (17.9) | 12 (20) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 4 | 17 (20.2) | 12 (20) | 5 (20.8) | |

| 5 | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Missing | 12 (14.3) | 11 (18.3) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Median time to RP, months (IQR) | 20 (15–47.8) | 16 (14–43) | 35 (15–45.5) | <0.001 |

| Median age at RP, year (IQR) | 68 (63–73) | 68.2 (63.3–73.3) | 68.9 (63.5–72.5) | 0.805 |

| Median PSA before RP, n (%) | 6.55 (4.8–8.9) | 6.1 (4.7–8.4) | 8.3 (5–11.3) | 0.007 |

| Median PSA doubling time before RP, month (IQR) | 2.2 (−2.2–3.9) | 2.2 (−2.6–3.8) | 2.1 (1.0–4.4) | 0.681 |

| Prostatectomy procedure, n (%) | ||||

| Robot-assisted | 111 (81.6) | 82 (90) | 29 (82.4) | 0.69 |

| Laparoscopic | 13 (9.6) | 9 (10) | 4 (9.2) | |

| Open | 12 (8.8) | 10 (0) | 2 (8.4) |

| . | Total . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 | 101 | 35 | |

| Median age at AS enrollment, year (IQR) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (62–70) | 65 (60–70) | 0.643 |

| Median PSA at AS enrollment, ng/ml (IQR) | 5.23 (4.43–6.73) | 5.22 (4.4–6.64) | 5.37 (4.7–7.2) | 0.522 |

| Median PSA density at AS enrollment, ng/ml/cc (IQR) | 0.16 (0.12–0.19) | 0.15 (0.12–0.19) | 0.16 (0.11–0.19) | 0.99 |

| Median prostate volume at AS enrollment, cc (IQR) | 36.5 (28.6–48.5) | 36.3 (28.6–48.8) | 39.1 (28–48.6) | 0.803 |

| MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | 84 (61.8) | 60 (59.4) | 24 (68.6) | 0.68 |

| PIRADS on MRI at diagnostic biopsy, n (%) | ||||

| ≤2 | 37 (44) | 24 (40) | 13 (54.2) | 0.422 |

| 3 | 15 (17.9) | 12 (20) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 4 | 17 (20.2) | 12 (20) | 5 (20.8) | |

| 5 | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Missing | 12 (14.3) | 11 (18.3) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Median time to RP, months (IQR) | 20 (15–47.8) | 16 (14–43) | 35 (15–45.5) | <0.001 |

| Median age at RP, year (IQR) | 68 (63–73) | 68.2 (63.3–73.3) | 68.9 (63.5–72.5) | 0.805 |

| Median PSA before RP, n (%) | 6.55 (4.8–8.9) | 6.1 (4.7–8.4) | 8.3 (5–11.3) | 0.007 |

| Median PSA doubling time before RP, month (IQR) | 2.2 (−2.2–3.9) | 2.2 (−2.6–3.8) | 2.1 (1.0–4.4) | 0.681 |

| Prostatectomy procedure, n (%) | ||||

| Robot-assisted | 111 (81.6) | 82 (90) | 29 (82.4) | 0.69 |

| Laparoscopic | 13 (9.6) | 9 (10) | 4 (9.2) | |

| Open | 12 (8.8) | 10 (0) | 2 (8.4) |

IQR, interquartile range; AS, acive surveillance; PSA, prostate specific antigen; PIRADS, Prostate Imaging Reporting And Data System; RP, radical prostatectomy.

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics of the analyzed cohort. In the off-criteria group, the median time to RP was significantly longer and the median PSA before RP was significantly higher than that in the on-criteria group (16 vs. 35 months, P < 0.001; 6.1 vs. 8.3 ng/ml, P = 0.007, respectively).

In this cohort, the median follow-up period from AS enrollment and from RP to the last follow-up or death was 71 months (interquartile range [IQR], 48–101.8) and 36 months (IQR, 15.3–59), respectively.

Primary endpoint: the comparison of pathological findings between the on-criteria and off- criteria RP

Although the percentage of pathological findings in the off-criteria group was lower than that in the on-criteria group, there were no significant differences in pathological findings between both groups (Table 2). In the cohort analyzed in our study, 52 (38.2%) patients had unfavorable pathologies on RP (Table 2). To evaluate the impact of adherence to the criteria on any of the unfavorable pathologies of RP, we further performed multivariate logistic analysis for unfavorable pathology, adjusted for age at diagnosis and initial PSA. Adherence to the criteria, the on-criteria and off-criteria, was not associated with unfavorable pathology of RP (OR,1.439; 95% CI, 0.628–3.295, P = 0.389).

Pathological findings stratified by adherence to the criteria at radical prostatectomy in patients opting for active surveillance

| . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any of unfavorable pathologies, n (%) | 41 (40.6) | 11 (31.4) | 0.421 |

| Pathological T3≤, n (%) | 12 (11.9) | 1 (2.8) | 0.183 |

| Gleason socre 4 + 3≤, n (%) | 33 (33) | 10 (28.6) | 0.679 |

| Extraprostatic extention, n (%) | 11 (10.9) | 2 (5.7) | 0.511 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion, n (%) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Pathological N-stage, n (%) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Resection margin, n (%) | 26 (25.7) | 9 (25.9) | 0.999< |

| . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any of unfavorable pathologies, n (%) | 41 (40.6) | 11 (31.4) | 0.421 |

| Pathological T3≤, n (%) | 12 (11.9) | 1 (2.8) | 0.183 |

| Gleason socre 4 + 3≤, n (%) | 33 (33) | 10 (28.6) | 0.679 |

| Extraprostatic extention, n (%) | 11 (10.9) | 2 (5.7) | 0.511 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion, n (%) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Pathological N-stage, n (%) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Resection margin, n (%) | 26 (25.7) | 9 (25.9) | 0.999< |

Pathological findings stratified by adherence to the criteria at radical prostatectomy in patients opting for active surveillance

| . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any of unfavorable pathologies, n (%) | 41 (40.6) | 11 (31.4) | 0.421 |

| Pathological T3≤, n (%) | 12 (11.9) | 1 (2.8) | 0.183 |

| Gleason socre 4 + 3≤, n (%) | 33 (33) | 10 (28.6) | 0.679 |

| Extraprostatic extention, n (%) | 11 (10.9) | 2 (5.7) | 0.511 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion, n (%) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Pathological N-stage, n (%) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Resection margin, n (%) | 26 (25.7) | 9 (25.9) | 0.999< |

| . | On-criteria . | Off-criteria . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any of unfavorable pathologies, n (%) | 41 (40.6) | 11 (31.4) | 0.421 |

| Pathological T3≤, n (%) | 12 (11.9) | 1 (2.8) | 0.183 |

| Gleason socre 4 + 3≤, n (%) | 33 (33) | 10 (28.6) | 0.679 |

| Extraprostatic extention, n (%) | 11 (10.9) | 2 (5.7) | 0.511 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion, n (%) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Pathological N-stage, n (%) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.999< |

| Resection margin, n (%) | 26 (25.7) | 9 (25.9) | 0.999< |

Secondary endpoint: PSA recurrence-free survival after RP in patients opting for AS, stratified by adherence to the criteria

No significant difference in PSA recurrence-free survival was found between the on-criteria and off-criteria groups (log-rank P = 0.828) (Fig. 2). The 3-year PSA recurrence-free survival rates in both groups were 96.7 and 95.5%, respectively (Fig. 2).

PSA recurrence was observed in eight of 136 patients who underwent RP (5.9%). Of these 136 patients, six (5.9%) were on-criteria and two (5.6%) were off-criteria. Sequential treatment after PSA recurrence included salvage radiation therapy in six patients and hormonal therapy and observation in a single patient, respectively. Only one patient died of a cause other than PC; however, none of the patients had metastasis.

Discussion

We examined whether pathological findings and oncological outcomes of RP differ depending on adherence to the criteria in patients who opt for AS. These patients, all with GS3 + 3, were prospectively enrolled in the PRIAS-JAPAN study. We observed that adherence to the criteria was not associated with unfavorable pathology and PSA recurrence-free survival, and the percentage of unfavorable pathology in the off-criteria group was lower than that in the on-criteria group. Furthermore, the median time from AS initiation to RP in the off-criteria group was 35 months. Our results suggest that AS can be safely continued if the criteria for definitive treatment are not met. This finding is relevant for both patients and AS providers in daily clinical practice.

Kaplan–Meier method for PSA recurrence-free survival in patients who opt for AS, stratified by adherence to the criteria. PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

AS follow-up includes regular PSA testing, digital rectal examination, magnetic resonance imaging and repeat prostate biopsy to monitor disease progression. According to every protocol worldwide, a trigger for definitive treatment in AS is a pathological reclassification of repeat prostate biopsy from the AS inclusion criteria (5–7). In our study, we compared the oncological outcomes of RP between patients adhering to this trigger (on-criteria) and those who did not (off-criteria). Although the percentage of any unfavorable pathological findings in the off-criteria group was lower than that in the on-criteria group, the differences between both groups were not statistically significant (Table 2). In on-criteria patients, pathological reclassification on repeat prostate biopsy was the trigger for RP, whereas in off-criteria patients, RP was performed without confirmation of pathological reclassification on repeat biopsy. Regarding the on-criteria patients, the median time to RP was 16 months, and 68.3% of the patients underwent RP within 2 years (Supplementary Fig. 1). This finding indicates that two-thirds of the on-criteria patients had reclassification at the first-year repeat biopsy; this explains the less unfavorable pathology in off-criteria patients than in on-criteria patients despite a relatively longer time to RP among off-criteria patients. Our results suggest that although half of the off-criteria patients underwent RP within 3 years of starting AS, the off-criteria patients may be safely deferred for a few more years of definitive treatment or may avoid RP due to the risk of overtreatment. In the future, magnetic resonance imaging and genomic examination will have a key role on optimizing the inclusion criteria and follow-up protocol for AS to avoid over- or undertreatment by deferred definitive treatment.

The median PSA before RP was significantly higher in the off-criteria group than in the on-criteria group (6.1 vs. 8.3 ng/ml, P = 0.007) (Table 1). The off-criteria group includes patients that underwent RP without considering the pathological findings of repeat prostate biopsy. Therefore, it was speculated that elevated PSA may be one of the triggers for definitive treatment. Despite PSA being an indicator of the disease status, using only elevated PSA as a trigger for RP may lead to low-risk PC overtreatment which may lead to adverse postoperative complications. Our study, PRIAS, was based on a rigorously set clinical study. However, less adherence to the protocol in real-world clinical practice has been reported (16). This suggests that AS providers should be aware that elevated PSA alone may lead to the initiation of misleading definitive treatment in daily clinical practice.

In recent years, various guidelines have supported the use of AS for intermediate PC (1,17). Moreover, several clinical studies have showed that AS for intermediate PC has good long-term outcomes in selected patients (18,19). However, each clinical study was based on single-arm outcomes, and strictly randomized controlled trials with surgery or radiotherapy were not available. In this study, the pathological findings and PSA recurrence-free survival of patients who underwent on-criteria RP were similar to those of patients who underwent off-criteria RP. This indicates that on-criteria RP does not lead to a loss of curative efficacy. The AS eligibility criteria of up to GS3 + 3 is safe. Hence, our data support the trend of relaxing the inclusion criteria for AS.

The strengths of this study are based on a global clinical trial using nationwide, multi-institutional data. However, this study had some limitations in the interpretation of the results. First, due to the retrospective data collection from the PRIAS-JAPAN data set, the reasons for the off-criteria definitive treatment were unavailable. Further research is required in this regard. Previous reports showed that the reasons for RP after AS were off-criteria in 24.4% of patients, of which 7.9% were a result of patient anxiety or requests and 16.5% were due to unknown causes (8). Second, we excluded patients who underwent RP within a year of enrollment because their disease status remained almost unchanged from the time of AS enrollment. Third, we excluded patients with GS3 + 4 at AS enrollment from the analysis. In the PRIAS-JAPAN study, the enrollment of GS3 + 4 patients was originally low (1.2%), as only two of 162 patients underwent RP in this study. Recently, the inclusion criteria for AS has been extended to a subset of GS3 + 4 patients (1,17); however, we excluded them due to their small number in this study. Fourth, the data of all patients analyzed in our study were obtained from a dataset in Japan. Therefore, further studies are needed to assess whether these findings can be generalized to non-Japanese cohorts as well. Finally, the postoperative observation period was relatively short, with a median follow-up period of 36 months. Therefore, we analyzed unfavorable pathology as the primary endpoint for oncological outcomes.

In conclusion, pathological findings of the off-criteria patients were not worse than those of the on-criteria patients; therefore, some off-criteria patients may have undergone overtreatment. We believe that our results provide a practical guide for AS providers in their daily clinical practice because AS providers and patients are concerned about missing curative opportunities.

Authors’ contributions

Conception or design of the work: Y.T., T.K. and M.S. Data acquisition: all authors. Analysis, interpretation and draft writing: Y.T. Critical revision: all authors, except Y.T. Final approval for publication: all authors.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to Dr Shintaro Narita, Dr Wataru Obara, Dr Mitsugu Kanehira, Dr Kazuo Nishimura, Dr Norio Nonomura, Dr Motohide Uemura, Dr Tadashi Matsuda, Dr Masatoshi Eto, Dr Kenichi Tabata, Dr Hideyasu Tsumura, Dr Hiroshi Okuno, Dr Takayoshi Miura, Dr Shusuke Akamatsu, Dr Osamu Ukimura, Dr Takumi Shiroishi, Dr Naoki Ninomiya, Dr Tomomi Kamba, Dr Yoji Murakami, Dr Yasuo Yamamoto, Dr Tadashi Murata, Dr Koji Inoue, Dr Hirohito Naito, Dr Kazuhiro Suzuki, Dr Yoshiyuki Miyazawa, Dr Yukio Kageyama, Dr Naoya Masumori, Dr Shin Egawa, Dr Masafumi Matsumura, Dr Ryotaro Tomida, Dr Tomohiko Ichikawa, Dr Nobuyoshi Takeuchi, Dr Yukio Naya, Dr Satoko Kojima, Dr Akira Miyajima, Dr Masahiro Nitta, Dr Haruki Kume, Dr Koichiro Akakura, Dr Hiroyoshi Suzuki, Dr Naoto Kamiya, Dr Hiro-omi Kanayama, Dr Yoshito Kusuhara, Dr Kiyotaka Kawashima, Dr Hideki Sakai, Dr Tomoaki Hakariya, Dr Toshiki Tanikawa, Dr Yoshihiko Tomita, Dr Takashi Kasahara, Dr Takayuki Sugiyama, Dr Hideaki Miyake, Dr Kenichiro Shiga, Dr Takeshi Ueno, Dr Takashige Abe, Dr Toshiyuki Kamoto, Dr Naoki Terada, Dr Norihiko Tsuchiya, Dr Hiroaki Matsumoto, Dr Seiichi Saito, Dr Takashi Kimura, Dr Hiromi Hirama and the PRIAS-JAPAN secretary, Akiko Mori, for their great contribution to this study.