-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Joseph Y Abrams, James L Mills, Lawrence B Schonberger, David Chang, Ryan A Maddox, Ermias D Belay, Ellen W Leschek, Suicides in National Hormone Pituitary Program Recipients of Cadaver-Derived Human Growth Hormone, Journal of the Endocrine Society, Volume 7, Issue 12, December 2023, bvad130, https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvad130

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Numerous reports of suicide among individuals who received cadaver-derived human growth hormone (c-hGH) through the National Hormone Pituitary Program (NHPP) raised the alarm for potentially increased suicide risk.

We conducted a study to assess suicide risk in the NHPP cohort and identify contributing factors to facilitate early recognition and intervention.

The study population consisted of patients receiving NHPP c-hGH starting from 1957, and cohort deaths with an ICD code consistent with suicide or possible suicide through 2020 were evaluated. Descriptive data were extracted from medical records. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) to compare the observed number of suicide deaths in the cohort to the expected number were calculated using general population suicide rates by sex, age group, and time period.

Among 6272 patients there were 1200 all-cause cohort deaths, of which 55 (52 male, 3 female) were attributed to suicide. Of these, 47 were identified by ICD code alone compared to an expected count of 37.8 (SMR = 1.25, 95% CI 0.91-1.66). Among male cohort members, the SMR was 1.33 (95% CI 0.97-1.78). Elevated risk of suicide was detected for cohort members aged 25-34 (SMR = 1.79, 95% CI 1.06-2.83) and during the period from September 19, 1985, to December 31, 1998 (SMR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.02-2.65).

Overall, the observed number of suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients was not significantly higher than expected. However, certain subgroups may be at elevated risk of suicide. Studies are needed to better understand the nature and magnitude of suicide risk among c-hGH recipients to facilitate early intervention to prevent suicide deaths.

In 1960, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the College of American Pathologists formed the National Pituitary Agency to coordinate collection and extraction of cadaver-derived human growth hormone (c-hGH) for basic and clinical research. Between 1963 and 1985, the National Hormone and Pituitary Program (NHPP), formerly the National Pituitary Agency, distributed c-hGH to treatment centers for clinical use in the United States. In 1985, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), a fatal neurodegenerative disease caused by pathogenic prions, was discovered in some c-hGH recipients, and administration of c-hGH for clinical use was immediately discontinued in the United States. To date, 34 NHPP c-hGH recipients have died from CJD, and 1 recipient who died from another cause had evidence of CJD on autopsy (unpublished data).

Since the NHPP halted treatment with c-hGH, some important observations have been made in the NHPP c-hGH cohort. In 1993, Fradkin et al reported that this population had a significantly increased rate of leukemia compared with the general population, noting that those treated with c-hGH had more leukemia risk factors, including radiation and tumors, which may have contributed to excess risk [1]. Mills et al reported in 2004 that this cohort had a 4-fold higher death rate than anticipated, with hypoglycemia and adrenal insufficiency accounting for more mortality than CJD, highlighting the importance of early intervention for and aggressive treatment of adrenal insufficiency due to hypopituitarism [2]. In 2013, Irwin et al reported that there was no evidence that NHPP c-hGH treatment increased the risk of death from Alzheimer or Parkinson disease, despite frequent exposure to neurodegenerative disease–associated proteins such as tau, Aβ, and α-synuclein [3].

The NHPP cohort has been monitored since 1985 for additional cases of CJD and for other adverse events. As a result of this surveillance, we identified numerous deaths by suicide among cohort members. This discovery led to the hypothesis that these individuals may be at greater risk for suicide, possibly due to concern about CJD risk or other quality of life issues linked to growth hormone (GH) deficiency [4]. To test this hypothesis, we conducted focused analyses to determine whether NHPP c-hGH recipients were actually at greater risk of suicide than the general US population, accounting for cohort demographics and study period.

Materials and Methods

An estimated 7700 children were treated with c-hGH through the NHPP. Thorough investigation of medical records yielded 6272 patients verified as NHPP c-hGH recipients who were available for analysis. Using telephone interviews and questionnaires, 84% of the verified recipients were contacted in 1988, at which time vital status was verified by cohort members and/or next of kin. Causes of death were gathered on deceased cohort members, and medical records were reviewed for deaths suspicious for CJD. After 1988, the National Death Index was assessed annually to identify NHPP cohort deaths, and death certificates were obtained and reviewed for all deceased cohort members. Medical records were examined for cohort deaths suspicious for CJD.

In 2021, when it was discovered that there were a large number of suicide deaths in the NHPP cohort, a review of all cohort deaths was performed. Cohort deaths with codes for suicide or self-inflicted injury listed in their death certificate (ICD-9 codes E950 through E959 and ICD-10 codes X60 through X84 and Y87.0) were classified as suicide deaths. Death certificates and medical records, when available, on cohort deaths without an ICD suicide code but with a suspicious cause of death, such as drug overdose, asphyxiation/strangulation, gunshot wound, and falling from a building or structure, were additionally reviewed for evidence of suicide. Demographic data were collected on all suicide deaths from the 1988 telephone interviews and questionnaires, death certificates, and medical records when available, including autopsy reports on cohort members who had autopsies performed. When available, information on adult height for suicide deaths (height at age ≥ 21 years for males and ≥19 years for females) was obtained from 1988 surveys and death certificates and compared with US general population height data [5].

To assess if the risk of suicide was elevated in the NHPP c-hGH recipients, we acquired multiple cause of mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics on people who died with an ICD code for suicide or self-inflicted injury (ICD-9 codes E950 through E959 and ICD-10 codes X60 through X84 and Y87.0) from 1979 to 2019. We collected information on sex, age at death, and year of death for all US deaths with a relevant ICD code anywhere in their death certificate. Using demographic data from annual intercensal population estimates, we calculated general population suicide rates by sex, 10-year age group, and ICD time period (ICD-9: 1979-1998; ICD-10: 1999-2019). These rates were applied to the recipient population to calculate the expected number of suicide deaths.

Person-years of observation were tallied for each c-hGH recipient from first c-hGH receipt to date last followed (defined as either September 1, 2021—the most recent date of mortality status verification—or date of death for deceased recipients). The appropriate general population suicide rates (accounting for sex, 10-year age group, and ICD time period) were applied to these person-years to determine the expected cumulative risk of suicide for each recipient. These risks were summed over the entire cohort to produce the total number of expected suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) along with 95% CIs were calculated to determine whether the observed counts of suicide among cohort members significantly differed from expected counts. Since general population suicide rates were calculated using ICD codes alone, the observed number of suicides counted within the cohort included only those identified by ICD code alone; the suicides identified through additional review were described in the study but not included in any SMR calculations. We also conducted further subanalyses to determine whether suicide rates were higher within different subgroups of c-hGH recipients, defined by sex, GH deficiency type (isolated or multiple), GH deficiency cause (idiopathic or organic), and 10-year age group. We also conducted subanalyses to determine whether suicide rates were different than expected when stratified by 4 time periods, with the cutpoints between periods defined as September 19, 1985 (the date the New England Journal of Medicine article first reported multiple cases of CJD among c-hGH recipients) [6]; January 1, 1999 (the date of implementation of ICD-10 mortality coding); and October 1, 2011 (the date of an influential scientific article describing a statistically lower CJD risk—and no observed CJD cases—among patients who only received c-hGH through NHPP after 1977) [7].

Demographic and clinical comparisons between NHPP c-hGH recipients who died of suicide and other cohort members were made using chi-square testing for categorical variables and t-tests with unequal variance for continuous variables. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 [8] and R version 4.1.2 [9].

Results

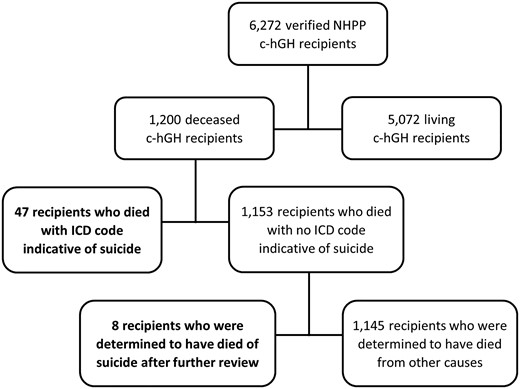

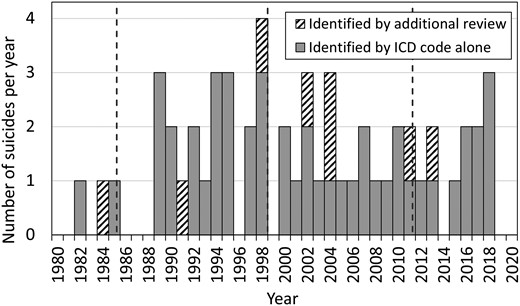

Demographics of the total confirmed NHPP cohort are compared with suicide deaths in the cohort in Table 1. There were 1200 confirmed deaths (849 male, 351 female) among the 6272 confirmed NHPP c-hGH recipients. Fifty-five (52 male, 3 female) of the deaths were determined to have resulted from suicide: 47 were identified through ICD codes, and 8 were identified through additional review of suspected suicide deaths (Fig. 1). The percent of suicide deaths that were male (95%) was significantly higher than the overall cohort percent male (68%, P < .0001). Suicide deaths in the cohort occurred at an age of 34.4 ± 11.2 years (mean ± SD), which was similar to mean age at death for the rest of the cohort (P = .9252). Distribution of race and mean duration of c-hGH treatment were approximately the same in the cohort suicide deaths and all other cohort deaths. The timeline of suicide deaths over time is shown in Fig. 2.

Flow chart of National Hormone Pituitary Program (NHPP) recipients of cadaver-derived human growth hormone (c-hGH), with suicide cases shown in bold.

Timeline of suicide deaths among NHPP c-hGH recipients, with suicides identified by ICD code alone in grey bars, and suicides identified by additional review in hatched bars. Dotted vertical lines represent the cutpoints between time periods (September 19, 1985; January 1, 1999; January 10, 2011).

Demographics of NHPP cohort: members who died of suicide compared with all other members

| . | NHPP cohort suicide deaths (n = 55)n (%) . | All other cohort membersa (n = 6217)n (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at death (years), mean ± SD | 34.4 ± 11.2 | 34.6 ± 15.0 | .9252 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 52 (95) | 4242 (68) | <.0001 |

| Female | 3 (5) | 1975 (32) | |

| Race | |||

| Black | 3 (5) | 444 (7) | .6282 |

| Non-Black | 52 (95) | 5773 (93) | |

| Type of GH deficiency | |||

| Isolated GH deficiency | 20 (36) | 1803 (29) | .3374 |

| Multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies | 23 (42) | 3354 (54) | |

| Not specified | 1 (2) | 121 (2) | |

| Not applicable | 11 (20) | 939 (15) | |

| Cause of GH deficiency | |||

| Idiopathic | 26 (47) | 3417 (55) | .7101 |

| Organic with tumor | 9 (16) | 1086 (17) | |

| Organic without tumor | 8 (15) | 614 (10) | |

| Unspecified cause | 1 (2) | 161 (3) | |

| Possible GH abnormality | 2 (4) | 99 (2) | |

| Not GH deficiency | 5 (9) | 435 (7) | |

| Not classifiable/missing | 4 (7) | 405 (7) | |

| Duration of GH treatment (years), mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 3.7 ± 3.0 | .7195 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | |||

| Yes | 11 (20) | 1444 (23) | .5725 |

| No | 44 (80) | 4773 (77) |

| . | NHPP cohort suicide deaths (n = 55)n (%) . | All other cohort membersa (n = 6217)n (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at death (years), mean ± SD | 34.4 ± 11.2 | 34.6 ± 15.0 | .9252 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 52 (95) | 4242 (68) | <.0001 |

| Female | 3 (5) | 1975 (32) | |

| Race | |||

| Black | 3 (5) | 444 (7) | .6282 |

| Non-Black | 52 (95) | 5773 (93) | |

| Type of GH deficiency | |||

| Isolated GH deficiency | 20 (36) | 1803 (29) | .3374 |

| Multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies | 23 (42) | 3354 (54) | |

| Not specified | 1 (2) | 121 (2) | |

| Not applicable | 11 (20) | 939 (15) | |

| Cause of GH deficiency | |||

| Idiopathic | 26 (47) | 3417 (55) | .7101 |

| Organic with tumor | 9 (16) | 1086 (17) | |

| Organic without tumor | 8 (15) | 614 (10) | |

| Unspecified cause | 1 (2) | 161 (3) | |

| Possible GH abnormality | 2 (4) | 99 (2) | |

| Not GH deficiency | 5 (9) | 435 (7) | |

| Not classifiable/missing | 4 (7) | 405 (7) | |

| Duration of GH treatment (years), mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 3.7 ± 3.0 | .7195 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | |||

| Yes | 11 (20) | 1444 (23) | .5725 |

| No | 44 (80) | 4773 (77) |

Values in bold depict statistically significant differences (P < .05).

Abbreviations: GH, growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

aIncludes only cohort members with complete data.

Demographics of NHPP cohort: members who died of suicide compared with all other members

| . | NHPP cohort suicide deaths (n = 55)n (%) . | All other cohort membersa (n = 6217)n (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at death (years), mean ± SD | 34.4 ± 11.2 | 34.6 ± 15.0 | .9252 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 52 (95) | 4242 (68) | <.0001 |

| Female | 3 (5) | 1975 (32) | |

| Race | |||

| Black | 3 (5) | 444 (7) | .6282 |

| Non-Black | 52 (95) | 5773 (93) | |

| Type of GH deficiency | |||

| Isolated GH deficiency | 20 (36) | 1803 (29) | .3374 |

| Multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies | 23 (42) | 3354 (54) | |

| Not specified | 1 (2) | 121 (2) | |

| Not applicable | 11 (20) | 939 (15) | |

| Cause of GH deficiency | |||

| Idiopathic | 26 (47) | 3417 (55) | .7101 |

| Organic with tumor | 9 (16) | 1086 (17) | |

| Organic without tumor | 8 (15) | 614 (10) | |

| Unspecified cause | 1 (2) | 161 (3) | |

| Possible GH abnormality | 2 (4) | 99 (2) | |

| Not GH deficiency | 5 (9) | 435 (7) | |

| Not classifiable/missing | 4 (7) | 405 (7) | |

| Duration of GH treatment (years), mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 3.7 ± 3.0 | .7195 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | |||

| Yes | 11 (20) | 1444 (23) | .5725 |

| No | 44 (80) | 4773 (77) |

| . | NHPP cohort suicide deaths (n = 55)n (%) . | All other cohort membersa (n = 6217)n (%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at death (years), mean ± SD | 34.4 ± 11.2 | 34.6 ± 15.0 | .9252 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 52 (95) | 4242 (68) | <.0001 |

| Female | 3 (5) | 1975 (32) | |

| Race | |||

| Black | 3 (5) | 444 (7) | .6282 |

| Non-Black | 52 (95) | 5773 (93) | |

| Type of GH deficiency | |||

| Isolated GH deficiency | 20 (36) | 1803 (29) | .3374 |

| Multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies | 23 (42) | 3354 (54) | |

| Not specified | 1 (2) | 121 (2) | |

| Not applicable | 11 (20) | 939 (15) | |

| Cause of GH deficiency | |||

| Idiopathic | 26 (47) | 3417 (55) | .7101 |

| Organic with tumor | 9 (16) | 1086 (17) | |

| Organic without tumor | 8 (15) | 614 (10) | |

| Unspecified cause | 1 (2) | 161 (3) | |

| Possible GH abnormality | 2 (4) | 99 (2) | |

| Not GH deficiency | 5 (9) | 435 (7) | |

| Not classifiable/missing | 4 (7) | 405 (7) | |

| Duration of GH treatment (years), mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 3.7 ± 3.0 | .7195 |

| Adrenal insufficiency | |||

| Yes | 11 (20) | 1444 (23) | .5725 |

| No | 44 (80) | 4773 (77) |

Values in bold depict statistically significant differences (P < .05).

Abbreviations: GH, growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

aIncludes only cohort members with complete data.

Approximately 83% of the NHPP cohort received c-hGH for GH deficiency. The remaining 17% were treated with c-hGH for other indications (eg, extreme idiopathic short stature, Turner syndrome, Russell–Silver syndrome). These percentages were similar for suicide deaths (78% and 22%). Adrenal insufficiency was present in 11 (20%) of suicide deaths in the cohort, which was similar to the percentage in the other cohort deaths (1444; 23%). Reasons for GH treatment in the suicide deaths included 11 brain tumors, 1 throat tumor, 3 traumatic head injuries, 1 septo-optic dysplasia, 2 congenital anomalies, 8 idiopathic multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies, 21 idiopathic isolated GH deficiencies, 4 idiopathic short statures, 3 small for gestational age, and 1 Noonan syndrome.

Means of suicide among males in the NHPP cohort included 22 by firearm, 15 by suffocation (hanging), 8 by poisoning (4 carbon monoxide, 4 drug overdose), 5 by jumping, 1 by drowning, and 1 by oral explosion (detonation of fireworks). One female suicide was due to drug overdose, 1 involved jumping from a building, and 1 was due to neck cutting.

Information on adult height was available for 26 (24 male, 2 female) of the 55 cohort suicide deaths. Adult height measurement for the 24 male suicide deaths can be seen in Fig. 3. Of the 24 male suicide deaths with known adult height, 16 (66%) were ≤−2.0 SDs from the mean general population males in height (≤64 inches or 163 cm), 4 (17%) were >−2.0 SDs and ≤−1.0 SDs (65-66 inches or 165-168 cm), and 4 (17%) were >−1.0 SDs (68-70 inches or 173-178 cm). Of the 2 female cohort suicide deaths with adult height measurement, 1 was 60 inches or 152 cm (−1.7 SDs) and 1 was 62 inches or 157 cm (−0.9 SDs).

![Normal bell curve for adult male height in the United States (including ±1, ±2 and ±3 standard deviation [STD] hashed lines) with overlying bar graph showing adult height in 24 males who died from suicide (male adult heights obtained at ≥21 years of age; adult heights not available for the remaining 28 male suicide deaths).](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jes/7/12/10.1210_jendso_bvad130/2/m_bvad130f3.jpeg?Expires=1747859261&Signature=B77-2aRfh3dNzk0tcKoEJHqRvmDQxDeLxchsRQBE89WzaLVinEl5pjv5gpdJKIozdx250bmz1Rk0HZoANQHeq8bHXLlulbEmYncWRr9CRTJ9GZvo-31zvHVciejByY0HbomGuskB29RBFJ8t-k14iJK1bO~W5GZ92nSeri~AsaIHiMwORLIe8kYqjGUdDaGsuD5dvMUkjxvW2w1mN88r1~RHJCMCbLrynVikFnL6gDX9maC8k80NVCL01OiHYUKuoycrte9zm9sHwxORlHOP4Wbt0xg6dPsyZtsdGPd9bCuSr4YzPd8w6GzIHnXy6gFbaEDPwGDqs-9B9Aiv6a4qWA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Normal bell curve for adult male height in the United States (including ±1, ±2 and ±3 standard deviation [STD] hashed lines) with overlying bar graph showing adult height in 24 males who died from suicide (male adult heights obtained at ≥21 years of age; adult heights not available for the remaining 28 male suicide deaths).

Of the 55 suicide deaths, 10 had a history of mental illness (7 depression, 1 bipolar disorder, 2 unspecified), 1 had a history of substance use disorder (alcohol plus illicit drugs), and 8 had a history of both mental illness and substance use disorder (3 depression plus alcohol, 5 unspecified).

After excluding 79 c-hGH recipients with missing data needed for person-time calculations, there were 6193 cohort members for whom expected risk of suicide was assessed, accounting for 233 369 person-years. There were 47 observed suicides in this group by ICD code alone, compared with an expected 37.8 suicides based on general population suicide rates (Table 2). The SMR for observed to expected cases was 1.25 (95% CI 0.91-1.66). Male c-hGH recipients had a SMR of 1.33 (95% CI 0.97-1.78), c-hGH recipients with isolated GH deficiency had a SMR of 1.59 (95% CI 0.96-2.48), and c-hGH recipients with organic GH deficiency had a SMR of 1.51 (95% CI 0.80-2.58).

Observed vs expected number of suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients, including analyses stratified by sex, GH deficiency type and GH deficiency cause

| Group . | Patients . | Person-years . | Observed suicidesa . | Expected suicides . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6193 | 233 369 | 47 | 37.8 | 1.25 (0.91-1.66) | .162 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1949 | 73 435 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.81) | .477 |

| Male | 4244 | 159 934 | 45 | 33.8 | 1.33 (0.97-1.78) | .073 |

| GH deficiency type | ||||||

| Isolated | 1807 | 70 284 | 19 | 12.0 | 1.59 (0.96-2.48) | .073 |

| Multiple | 3351 | 124 707 | 18 | 19.6 | 0.92 (0.54-1.45) | .829 |

| GH deficiency cause | ||||||

| Idiopathic | 3415 | 135 861 | 22 | 22.7 | 0.97 (0.61-1.47) | .996 |

| Organic | 1702 | 57 595 | 13 | 8.6 | 1.51 (0.80-2.58) | .196 |

| Group . | Patients . | Person-years . | Observed suicidesa . | Expected suicides . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6193 | 233 369 | 47 | 37.8 | 1.25 (0.91-1.66) | .162 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1949 | 73 435 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.81) | .477 |

| Male | 4244 | 159 934 | 45 | 33.8 | 1.33 (0.97-1.78) | .073 |

| GH deficiency type | ||||||

| Isolated | 1807 | 70 284 | 19 | 12.0 | 1.59 (0.96-2.48) | .073 |

| Multiple | 3351 | 124 707 | 18 | 19.6 | 0.92 (0.54-1.45) | .829 |

| GH deficiency cause | ||||||

| Idiopathic | 3415 | 135 861 | 22 | 22.7 | 0.97 (0.61-1.47) | .996 |

| Organic | 1702 | 57 595 | 13 | 8.6 | 1.51 (0.80-2.58) | .196 |

Abbreviations: c-hGH, cadaver-derived human growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

aOnly deaths with suicide ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes are included.

Observed vs expected number of suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients, including analyses stratified by sex, GH deficiency type and GH deficiency cause

| Group . | Patients . | Person-years . | Observed suicidesa . | Expected suicides . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6193 | 233 369 | 47 | 37.8 | 1.25 (0.91-1.66) | .162 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1949 | 73 435 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.81) | .477 |

| Male | 4244 | 159 934 | 45 | 33.8 | 1.33 (0.97-1.78) | .073 |

| GH deficiency type | ||||||

| Isolated | 1807 | 70 284 | 19 | 12.0 | 1.59 (0.96-2.48) | .073 |

| Multiple | 3351 | 124 707 | 18 | 19.6 | 0.92 (0.54-1.45) | .829 |

| GH deficiency cause | ||||||

| Idiopathic | 3415 | 135 861 | 22 | 22.7 | 0.97 (0.61-1.47) | .996 |

| Organic | 1702 | 57 595 | 13 | 8.6 | 1.51 (0.80-2.58) | .196 |

| Group . | Patients . | Person-years . | Observed suicidesa . | Expected suicides . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6193 | 233 369 | 47 | 37.8 | 1.25 (0.91-1.66) | .162 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1949 | 73 435 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.81) | .477 |

| Male | 4244 | 159 934 | 45 | 33.8 | 1.33 (0.97-1.78) | .073 |

| GH deficiency type | ||||||

| Isolated | 1807 | 70 284 | 19 | 12.0 | 1.59 (0.96-2.48) | .073 |

| Multiple | 3351 | 124 707 | 18 | 19.6 | 0.92 (0.54-1.45) | .829 |

| GH deficiency cause | ||||||

| Idiopathic | 3415 | 135 861 | 22 | 22.7 | 0.97 (0.61-1.47) | .996 |

| Organic | 1702 | 57 595 | 13 | 8.6 | 1.51 (0.80-2.58) | .196 |

Abbreviations: c-hGH, cadaver-derived human growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

aOnly deaths with suicide ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes are included.

When broken down by age group, c-hGH recipients aged 25 to 34 years had a higher than expected risk of suicide (SMR = 1.79, 95% CI 1.06-2.83) (Table 3). We also assessed suicide risk by time period: c-hGH recipients had a higher than expected risk of suicide from September 19, 1985, through December 31, 1998 (SMR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.02-2.65) (Table 4).

Observed vs expected number of suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients by age groupa

| Age group . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-14 years | 29 310 | 0 | 0.2 | — | 1.000 |

| 15-24 years | 56 171 | 9 | 8.6 | 1.04 (0.48-1.98) | .991 |

| 25-34 years | 55 003 | 18 | 10.1 | 1.79 (1.06-2.83) | .030 |

| 35-44 years | 50 844 | 12 | 9.8 | 1.23 (0.64-2.15) | .553 |

| 45-54 years | 32 187 | 6 | 7.1 | 0.85 (0.31-1.85) | .878 |

| 55-64 years | 8759 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.54 (0.01-3.01) | .895 |

| 65-74 years | 1075 | 1 | 0.2 | 4.86 (0.12-27.10) | .372 |

| 75-84 years | 21 | 0 | 0.0 | — | 1.000 |

| Age group . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-14 years | 29 310 | 0 | 0.2 | — | 1.000 |

| 15-24 years | 56 171 | 9 | 8.6 | 1.04 (0.48-1.98) | .991 |

| 25-34 years | 55 003 | 18 | 10.1 | 1.79 (1.06-2.83) | .030 |

| 35-44 years | 50 844 | 12 | 9.8 | 1.23 (0.64-2.15) | .553 |

| 45-54 years | 32 187 | 6 | 7.1 | 0.85 (0.31-1.85) | .878 |

| 55-64 years | 8759 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.54 (0.01-3.01) | .895 |

| 65-74 years | 1075 | 1 | 0.2 | 4.86 (0.12-27.10) | .372 |

| 75-84 years | 21 | 0 | 0.0 | — | 1.000 |

Values in bold depict categories with significant differences between observed and expected suicide counts.

Abbreviations: c-hGH, cadaver-derived human growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

aMales and females included.

Observed vs expected number of suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients by age groupa

| Age group . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-14 years | 29 310 | 0 | 0.2 | — | 1.000 |

| 15-24 years | 56 171 | 9 | 8.6 | 1.04 (0.48-1.98) | .991 |

| 25-34 years | 55 003 | 18 | 10.1 | 1.79 (1.06-2.83) | .030 |

| 35-44 years | 50 844 | 12 | 9.8 | 1.23 (0.64-2.15) | .553 |

| 45-54 years | 32 187 | 6 | 7.1 | 0.85 (0.31-1.85) | .878 |

| 55-64 years | 8759 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.54 (0.01-3.01) | .895 |

| 65-74 years | 1075 | 1 | 0.2 | 4.86 (0.12-27.10) | .372 |

| 75-84 years | 21 | 0 | 0.0 | — | 1.000 |

| Age group . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-14 years | 29 310 | 0 | 0.2 | — | 1.000 |

| 15-24 years | 56 171 | 9 | 8.6 | 1.04 (0.48-1.98) | .991 |

| 25-34 years | 55 003 | 18 | 10.1 | 1.79 (1.06-2.83) | .030 |

| 35-44 years | 50 844 | 12 | 9.8 | 1.23 (0.64-2.15) | .553 |

| 45-54 years | 32 187 | 6 | 7.1 | 0.85 (0.31-1.85) | .878 |

| 55-64 years | 8759 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.54 (0.01-3.01) | .895 |

| 65-74 years | 1075 | 1 | 0.2 | 4.86 (0.12-27.10) | .372 |

| 75-84 years | 21 | 0 | 0.0 | — | 1.000 |

Values in bold depict categories with significant differences between observed and expected suicide counts.

Abbreviations: c-hGH, cadaver-derived human growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

aMales and females included.

Observed vs expected number of suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients by time period

| Time period . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 9/19/1985 | 43 174 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.79) | .467 |

| 9/19/1985-12/31/1998 | 74 556 | 19 | 11.2 | 1.70 (1.02-2.65) | .042 |

| 1/1/1999-9/30/2011 | 67 154 | 16 | 12.6 | 1.27 (0.73-2.07) | .401 |

| 10/1/2011 and after | 48 484 | 10 | 9.9 | 1.01 (0.48-1.85) | 1.000 |

| Time period . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 9/19/1985 | 43 174 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.79) | .467 |

| 9/19/1985-12/31/1998 | 74 556 | 19 | 11.2 | 1.70 (1.02-2.65) | .042 |

| 1/1/1999-9/30/2011 | 67 154 | 16 | 12.6 | 1.27 (0.73-2.07) | .401 |

| 10/1/2011 and after | 48 484 | 10 | 9.9 | 1.01 (0.48-1.85) | 1.000 |

Values in bold depict categories with significant differences between observed and expected suicide counts.

Abbreviations: c-hGH, cadaver-derived human growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

Observed vs expected number of suicides among NHPP c-hGH recipients by time period

| Time period . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 9/19/1985 | 43 174 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.79) | .467 |

| 9/19/1985-12/31/1998 | 74 556 | 19 | 11.2 | 1.70 (1.02-2.65) | .042 |

| 1/1/1999-9/30/2011 | 67 154 | 16 | 12.6 | 1.27 (0.73-2.07) | .401 |

| 10/1/2011 and after | 48 484 | 10 | 9.9 | 1.01 (0.48-1.85) | 1.000 |

| Time period . | Person-years . | Observed . | Expected . | SMR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 9/19/1985 | 43 174 | 2 | 4.0 | 0.50 (0.06-1.79) | .467 |

| 9/19/1985-12/31/1998 | 74 556 | 19 | 11.2 | 1.70 (1.02-2.65) | .042 |

| 1/1/1999-9/30/2011 | 67 154 | 16 | 12.6 | 1.27 (0.73-2.07) | .401 |

| 10/1/2011 and after | 48 484 | 10 | 9.9 | 1.01 (0.48-1.85) | 1.000 |

Values in bold depict categories with significant differences between observed and expected suicide counts.

Abbreviations: c-hGH, cadaver-derived human growth hormone; NHPP, National Hormone Pituitary Program; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

Discussion

While there have been previous reports of suicides among GH recipients [10, 11], our study is the first to systematically assess whether GH recipients have increased suicide risks compared with the general population. Careful review of the NHPP c-hGH recipient cohort, accounting for sex, age, and time period, did not reveal an elevated risk of suicide. However, stratified analyses showed that some subgroups within the cohort may be at higher risk.

Our results showed that cohort members had an elevated risk of suicide between the ages of 25 and 34 years and between September 19, 1985 and December 31, 1998. Because cohort members often started c-hGH treatment at around the same age (interquartile range 6.6-13.6 years) and during roughly the same period (interquartile range 8/3/1974-5/15/1982), the bulk of the cohort passed through each age category during similar years, hindering the ability to differentiate between potential effects of age and time period. One potential explanation for elevated suicide risks from 19 September, 1985, through December 31, 1998, could be that news of possible infection with an agent that caused a 100% fatal disease increased anxiety and suicidal thoughts among cohort members. Conversely, the increased risk of suicide could be linked to age as opposed to time period, for instance, if short stature and/or other health issues related to GH deficiency cause particularly severe distress among young adults. Many NHPP cohort members had 1 or more known risk factors for suicide, including short stature, chronic illness, adverse childhood experience, mental illness, and substance use disorder.

Of the 24 male suicide deaths in the cohort for whom adult height data were available, 15 (63%) met the definition of short stature and 6 (25%) met the definition of extreme short stature [12]. The available male adult heights in the cohort suicide deaths (mean ± SD; 63.0 ± 3.3 inches, −2.3 ± 1.2 SDS) are comparable with achieved male adult heights reported in the literature for people treated with c-hGH for GH deficiency during a similar period [12-19]. Magnusson et al found that for Swedish men in the Military Service Conscription Register between 1968 and 1999, a 5-cm (2-inch) increase in height was associated with a 9% decrease in suicide, translating to a 2-fold higher risk of suicide in short men than in tall men [20]. Whitley et al described attempted and successful suicides among all men born in Sweden between 1950 and 1976, finding that the tallest men had a 40% reduction in hazard compared with the shortest men, and a 1 SD increase in height was associated with a 16% decrease in risk of attempted suicide [21].

Suicide method was similarly distributed in NHPP cohort males and in males in the general population. For males in the general population, firearms are consistently the most common means of committing suicide, followed by suffocation, and then poisoning [22]; these were also the most common means of suicide among males in the NHPP cohort. In the general population, the most common means of suicide in females are poisoning, firearms, and suffocation [22]; only 1 of the 3 suicides in female cohort members involved 1 of these methods (poisoning via drug overdose).

Chronic illness, including adrenal insufficiency, brain tumor, throat tumor, traumatic head injury, septo-optic dysplasia, congenital anomaly, and idiopathic multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies, was present in 27 (49%) of the cohort suicide deaths. Associations between chronic illness, adverse childhood experiences, and suicide have been well described. Within a random sample of 7461 adults in England, those with some form of disability were 4 times more likely to have attempted suicide [23]. In a study of Canadians between 15 and 30 years of age, suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts were more common among participants with chronic illness compared with controls [24].

Eleven (20%) of the NHPP cohort members who died by suicide were pediatric brain tumor survivors. In 2013, Brinkman et al reviewed results of psychological screening on 391 pediatric brain tumor survivors in the Neuro-Oncology Outcomes Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Children's Hospital of Boston between 2003 and 2007. Suicidal ideation was present in 11.7% of the survivors at 1 or more evaluations and 1.6% had documented suicide attempts. History of depression was the strongest predictor of suicidal ideation [25].

At least 19 (35%) of the 55 cohort members who died by suicide suffered from mental illness and/or substance use disorder. This may be an underestimate of the true percentage with substance use disorders or mental illness because these data came from an interview when most of the cohort was young, and the only updates came from death certificates and autopsy reports. There is a considerable body of literature supporting the role of mental illness and substance use disorder in suicide risk. Wilcox et al found that compared with the general population, individuals with alcohol use disorders had an almost 10-fold greater number of suicides; people with opioid use disorders had an almost 14-fold greater number of suicides; and mixed drug users were about 17 times more likely to die by suicide [26]. Flensborg-Madsen et al found that alcohol use disorders were linked to a significantly increased risk of suicide [27]. In a review of addiction and suicide, Yuodelis-Flores et al found that substance use and intoxication intensify the risk of suicidal behavior, and that mental illness is particularly associated with suicidal behavior in addictive disorders [28]. Of ∼800 000 suicides documented worldwide in 2015, the majority were related to psychiatric diseases [29].

Strengths of this investigation include analysis of a well-characterized cohort of c-hGH recipients that was queried annually for cohort deaths and the careful review of death certificates for the extraction of details regarding cause of death. Detailed demographic and clinical data on cohort members allowed for the first systematically calculated assessment of suicide risks among GH recipients. One potential weakness is generalizability, as the study cohort consisted specifically of US residents receiving NHPP c-hGH up to 1985. Therefore, study results may not be applicable to all other GH recipients. Calculations of SMRs were based on ICD code data and may be affected by inaccuracies in these records. This was an exploratory study of suicide risks among c-hGH recipients; additional studies may be needed to verify these results.

Conclusion

While risk of suicide for NHPP c-hGH recipients was not significantly higher than expected, certain subgroups may be at elevated risk. Multiple factors could have contributed to a potential increased risk of death by suicide for some members of the cohort, including short stature, chronic illness, adverse childhood experiences, mental illness, and substance use disorder. Individuals receiving GH for indications similar to those in members of the NHPP cohort could potentially have elevated risk for death by suicide. Medical caregivers should be cognizant of suicide risk during and after GH administration to facilitate early intervention to prevent suicide deaths. Particular attention should be paid to individuals in the 25- to 34-year-old age range, when risk appears to be significantly greater than that in the general population. GH recipients, particularly those falling into this age category, should be screened and monitored for depression and suicidality. Studies evaluating those who are receiving or have received GH should be undertaken to better understand the nature and magnitude of suicide risk in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Westat researchers, Lesa Houser, Data Research Associate, and Margaret Camarca, Senior Study Director, for their hard work on the surveillance project that generates important data on the cohort participants. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Interagency Coordinating Committee (including representatives from the NIH, CDC and FDA), which has overseen the surveillance project since its inception.

Funding

No grants or fellowships supported the writing of this paper.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of all data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

References and Notes

Abbreviations

- c-hGH

cadaver-derived human growth hormone

- CJD

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

- GH

growth hormone

- NHPP

National Hormone Pituitary Program

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- SMR

standardized mortality ratio