-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paolo Acciari, Facundo Alvaredo, Salvatore Morelli, The Concentration of Personal Wealth in Italy 1995–2016, Journal of the European Economic Association, Volume 22, Issue 3, June 2024, Pages 1228–1274, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvae002

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We estimate the distribution of wealth in Italy between 1995 and 2016 using a novel source of inheritance tax files, combined with surveys and national accounts. We find that the level of wealth concentration is in line with other European countries; however, its time trend appears more in line with the US, showing a significant increase over the period studied. The country exhibits one of the greatest declines in the wealth share of the bottom 50%. The paper also shows that age plays a marginal role in explaining wealth concentration. Changes in savings, instead, are the predominant force behind the increase in wealth inequality, even at the top. Equity prices also account for a large share of wealth growth above the 99th percentile, whereas changes in house prices play only a minor role. Finally, we document the growing concentration of life-time wealth transfers, and their increasingly favorable tax treatment.

1. Introduction

Italy has one of the highest wealth-to-income ratios in the developed world: Its stock of private wealth is equivalent to 7 years of national income.1 Yet little is known about how this wealth is distributed. This paper presents estimates of Italy’s distribution of personal wealth between 1995 and 2016, with a focus on high-end wealth groups, based on a newly compiled dataset of the full records of inheritance tax files, combined with household surveys and the national balance sheet, and triangulated with additional sources to more accurately assess wealth concentration and its drivers.

Inheritance tax data, never extensively utilized before in Italy, are crucial to widen the windows of observation on the distribution of wealth. While other sources provide direct or indirect information about wealth holdings, few of them are, currently, straightforwardly applicable to the Italian case. Apart from the property tax, Italy does not levy a wealth tax, and distributional information on investment is not readily available due to the fact that personal income tax on most financial income is withheld at source. This makes the application of the capitalization method impractical at present.2 We also distribute personal wealth from national accounts (NA), as discussed in Alvaredo et al. (2020), providing a new perspective on personal wealth in Italy compared with previous studies that rely solely on household surveys.

This paper thus presents the first set of comprehensive estimates of wealth distribution and concentration that complement those from the Survey of Households on Income and Wealth (SHIW), administered by the Bank of Italy since the late 1980s. Utilizing multiple data sources to study wealth inequality is essential, given that every source comes with its advantages and drawbacks. Moreover, household surveys are generally deemed to be less suited to capturing the wealth holdings at the very top, largely due to the lack of over-sampling of wealthy households, as well as the differential non-response and under-reporting rates across wealth classes (Vermeulen 2017; Kennickell 2019). Inheritance tax data, on the other hand, increase the probability of better covering top wealth groups, even taking into account the existence of tax avoidance and evasion. Administrative data guarantee higher coverage of the asset holdings of over half of Italy’s decedents (more than 60% in recent years).3

Our findings indicate that wealth concentration is higher and displays a more pronounced upward trend compared with what household surveys have been able to capture. According to the SHIW, the share accruing to the richest 1% (half a million adults) remained relatively unchanged between 1995 and 2016, at 14%. These figures align with previous research conducted by Brandolini et al. (2004) and Cannari and D’Alessio (2018b). However, our estimates reveal a different picture, suggesting that the share of the top 1% increased from 16% in 1995 to 22% in 2016, despite a considerably higher wealth aggregate. Furthermore, the share accruing to the richest 5,000 adults (the top 0.01%) nearly tripled, rising from 1.8% to 5%.

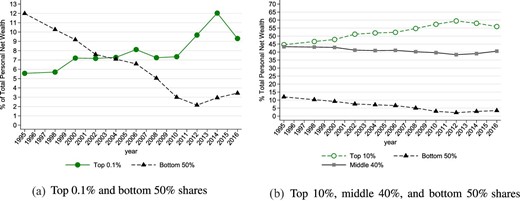

As a preview of the main results, Figure 1 shows a stark inversion of fortunes since 1995. The richest 0.1% saw a twofold increase in their real net wealth per adult (from €7.6 million to €15.8 million at 2016 prices), doubling its share from 5.5% to 9.3%. In contrast, the share controlled by the poorest 50% has decreased from 11.7% in 1995 to 3.5% in recent years. This corresponds to an 80% drop in the average net wealth (from €27,000 to €7,000 at 2016 prices). Strong concentration increases were also recorded for the richest 10%, whose share went from 44% in 1995 to 56% in 2016. In 1995, the share of the middle 40% was very similar to that of the top 10%; however, it has declined over time by almost 5 percentage points. Consequently, Italy stands out as one of the countries with the strongest decline in the wealth share of the bottom 50%.

The inversion of fortunes between 1995 and 2016. The graphs show the shares of total personal net wealth accrued by the bottom 50% of the adult population (25 million individuals in 2016) ranked by total net wealth, the richest 0.1% (50,000 individuals), the top 10%, the middle 40%, and the bottom 50%, benchmark definition.

Our series are also triangulated with external evidence: namely Forbes rich list (which tracks the evolution of the share of the five richest individuals since 1988, and the richest 10 since 2001) and Credit Suisse Report (Davies, Lluberas, and Shorrocks 2017), both of which are broadly consistent with the evidence assembled here.

The use of tax data entails costs and requires adjustments. These include aligning real estate valuations with market prices, converting decedents’ distribution to living wealth holders using the mortality multiplier method, estimating the wealth of the unidentified population through household surveys, and addressing non-taxable assets and potential under-reporting.

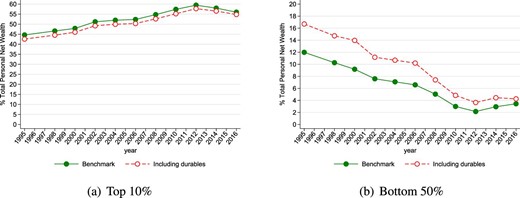

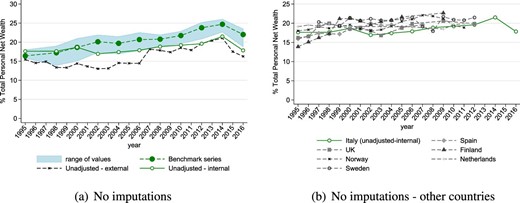

The benchmark approach in this study is to fully distribute the household sector’s balance sheet from NA. While acknowledging that the balance sheet might not provide precise figures (as discussed in Section 2), it serves as a reasonable indicator (enshrined in official statistics) for tracking aggregate development over time and allows for better cross-country comparisons. However, this requires imputing unobserved wealth from tax records and household surveys. In any case, we also present series based on tax and survey data before imputations, as well as series that incorporate unreported offshore wealth and household durables. In our view, this multi-series approach, that is, one that offers the opportunity to compare information from different and competing data sources, is preferable to the alternative option of looking at one and only one series resulting from the combination of those sources.

Our benchmark series thus emerges from a wider range of values, representing different methods of estimation. This approach demonstrates that the key findings regarding wealth concentration evolution in Italy are not solely driven by the imputations. It also enables comparisons with historical series that are not scaled to the NA (Gabbuti and Morelli 2023 for Italy; Piketty, Postel-Vinay, and Rosenthal 2006 for France; Alvaredo and Saez 2009 for Spain; Alvaredo, Atkinson, and Morelli 2018 for the UK; and Roine and Waldenström 2015 for Finland, Norway, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland etc.) as well as to recent work on the US, France, Spain, and Germany (Saez and Zucman 2016; Batty et al. 2019; Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret, and Piketty 2021; Martínez-Toledano 2017; Albers, Bartels, and Schularick 2020), which follows the Distributional National Accounts (DINA) framework (Alvaredo et al. 2016, 2020).

The level of wealth concentration observed in Italy appears to be in line with other European countries; however, its evolution over time is closer to that found in the US, showing a sharp increase in recent years. By contrast, whereas the share of Italy’s middle 40% (P50–90) remains relatively high, the share of the bottom 50% experienced the strongest decline since the mid-1990s when compared with other countries.

The paper devotes substantial space to discussing measurement. It also sheds light on the determinants of the wealth inequality trends revealed by our analysis, thus making important contributions to the literature.

First, our estimates suggest that age and life-cycle factors do not explain the current level of wealth concentration. Second, we document how the heterogeneity of portfolios across the distribution influences the dynamics of wealth concentration. Whereas housing wealth plays a significant role for the middle 40% group, the accumulation of wealth at the top is primarily driven by financial and business assets. Moreover, changes in currency and deposits, along with increasing levels of indebtedness, contribute significantly to the net wealth dynamics of the bottom 50% group. Third, we investigate the relative role of savings and asset prices. Our results show that changes in total savings (defined as the sum of direct changes in the volume of indebtedness, deposits, and valuables, and any residual changes in the asset value that is not accounted for by changes in the asset prices) account for a very large portion of growth in net wealth, both in the overall population and within the top decile. Interestingly, this occurred despite a sustained declining trend in the saving capacity of households over recent decades.

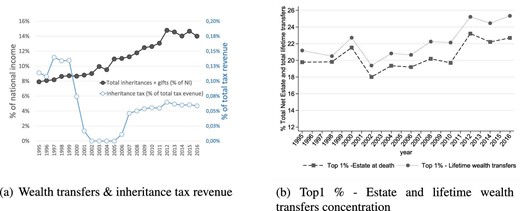

Our analysis of the joint distribution of income and wealth also reveals that the probability of top 1% and top 0.1% of labor income earners climbing to the top 1% of the wealth distribution doubled between 2001 and 2014. Although changes to asset prices are not the predominant force behind the increase in wealth concentration, certain interesting findings are worth noting. Our results show that little of the change in wealth recorded between 1995 and 2016 across the distribution can be attributed to changes in house prices.4 On the contrary, changes in equity prices account for a large share of wealth growth above the 99th percentile and are practically irrelevant in the middle and bottom parts of the distribution (with the exception of the 1995–2008 sub-period). Lastly, we present new evidence on the increasing significance of wealth transfers, such as inheritance and inter vivos gifts, as well as their growing concentration at the top. Moreover, we find that wealthy inheritors have experienced a decreasing tax burden over the past two decades, following tax policy changes that have undermined the progressive nature of inheritance and gift taxes. These changes in the patterns of wealth transfers and their impact on long-term wealth concentration dynamics have been overlooked in empirical studies.

The paper is structured as follows. The second section describes the concept of net wealth and the nature of the aggregate wealth of the household sector. Section 3 dwells on the structure of the inheritance tax in Italy, the currently available data, and the mortality multiplier method. It goes on to describe the valuation of specific asset classes as well as the wealth of the missing population and tax-exempt assets. The fourth section presents our main empirical findings on the evolution of wealth inequality and concentration in Italy, including the comparison of our estimates with those available in other countries. The fifth section triangulates our evidence with that of alternative sources of data. Section 6 discusses the role of different factors in driving wealth concentration in Italy. Our final section briefly presents a series of robustness checks. Our concluding remarks follow.

2. The Macro Dimension: The Growing Relevance of Personal Wealth in Italy

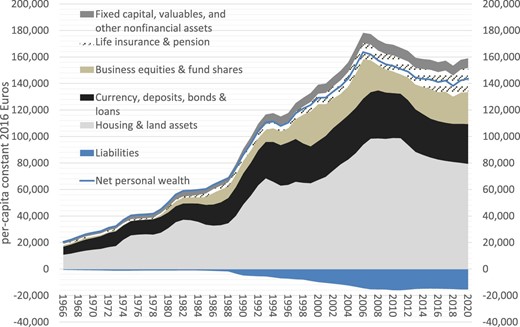

According to the national balance sheets, Italian households are among the wealthiest and least indebted of the rich economies. Net wealth per capita, taken as the sum of all financial and real assets minus liabilities, was €21,000 (2016 prices) in 1966. By 2006, just before the onset of the financial crisis, this figure had increased eight-fold to €164,000. As shown in Figure 2, it then dropped to €141,000 in 2016. A fall as remarkable as 14% did not occur in any of the other advanced economies with the exception of Spain.

The growing relevance of households’ per capita net wealth. The graph shows stacked estimates of five different asset classes (Housing and land; currency, deposits, and bonds; directly held shares in listed and unlisted corporations, other equity in quasi-corporations, and investment fund shares; life insurance reserves and the balance of private pension funds; fixed capital and other non financial assets of small personal businesses of producer households (such as plant, machinery, equipment, inventories, and goodwill); and liabilities held by the household sector excluding the non-profit sector serving households). The series assembles data from the balance sheets and the financial accounts from the Bank of Italy, ISTAT, and WID.world. The blue line in the graph shows the evolution of households’ net wealth derived from the sum of all asset classes minus all liabilities. Online Appendix A provides more information about how we reconstruct the series.

Over the past five decades, housing and land assets accounted for about 50% of personal sector wealth. Official balance sheets, published jointly by the Bank of Italy and ISTAT, only cover the household sector including non-profit organizations. As detailed in the Online Appendix A.3, our analysis focuses on the household sector. The value of direct equity holdings, investment funds, and indirect financial securities through life insurance and private pension funds increased as a proportion of total gross assets, from 14% to 23%. Savings, current accounts, currency, and bonds declined from 24% to 17%, as did the value of fixed capital, valuables, and other non-financial assets from 5.8% to 3.5%. Personal debt, worth €15,000 per capita, almost doubled as a share of total gross wealth since 1995. Despite this, Italy maintains one of the lowest indebtedness levels currently recorded in the rich world, in contrast to the situation of the debt of the public sector.

Italy also has one of the highest ratios of private wealth to national income. Over 7 years of national income would be needed to account for the net worth of the household and non-profit sectors. This ratio was 2 around 1970. It is now close to 6 in other rich countries like France, Japan, and the UK, and to 5 in the US and Germany.

To understand this context in more detail, we now discuss the concept of net wealth and present current challenges to its accurate measurement, including the exclusion of particular assets, and the undervaluation of non-marketable assets and property wealth.

The Meaning of Net Wealth.

Wealth holding, by shaping one’s current and future consumption and earning potential, represents a unique determinant of the well-being and the living standards of individuals and households. The implications of wealth holding go well beyond the direct effects on consumption opportunities. Specific assets, such as company shares, may convey direct or indirect control over productive resources and, similarly, may also provide substantial power of influence in society as well as a clear mark of status. The level of individual wealth holding also affects risk-taking behavior, and can grant or deny access to specific investments, education, or job opportunities. Hence, the aggregate level of wealth, its composition, and its distribution together affect the functioning of the economy and the structure of society, and may also guide the structure of tax policies.

The central concept of net wealth employed in this paper refers to the current value of all tangible and intangible assets that are under the control of the households, which provide economic benefits to the holders, and over which property rights can be exercised. The assets may be financial, such as current or savings accounts, stocks, bonds, financial assets held in private pension accounts, and life insurance reserves, or they may be real assets, such as land, houses, non-residential buildings, and tangible and intangible fixed capital (plant, machinery, equipment, inventories, goodwill, software, and intellectual property rights). Thus, our definition of personal net wealth is aligned with that of the 2008 SNA (UN 2010) and the 2010 European System of Accounts (EU 2013). The latter definition is grounded in conventional, neoclassical economic theory, where wealth represents a store of value for present and future consumption. It is worth stressing, however, that there is no unique definition of wealth, and that the methods of valuation matter substantially.

The definition of wealth under the SNA excludes certain assets that are particularly relevant for specific groups of the distribution. For instance, NA only imprecisely capture the wealth that households own outside of the country of residence, most likely leading to assets of high-end groups going unrecorded. In this paper, we carry out robustness exercises, which incorporate estimates of unreported offshore bank deposits and portfolios of financial securities.

Antiques, artworks, and valuables are included in the SNA definition, but consumer durables (vehicles, electronic goods, and other household possessions) are not. These are instead considered within the consumption section of the NA. These assets are generally more evenly distributed than total wealth, and their inclusion may reduce the estimated level of wealth inequality.5 In this paper, we include durables and household goods in alternative estimates of wealth concentration.

Furthermore, NA do not account for state pension wealth or unfunded defined benefit pension plans, which, instead, would likely add to the middle and the bottom of the distribution.6 However, the estimation of public pension assets is surrounded with considerable uncertainty: One needs to estimate the expected retirement age, the individual’s income pattern over the life-cycle, and the evolution of pension tax policies; the net present value is also influenced by the choice of discount factor as well as the life expectancy of each individual and the mortality probability of their spouse. Moreover, future benefits from public pensions cannot be disposed of, transferred in full to other people, or used as collateral, and are not under the control of the rights holders. Hence, the exclusion of public pension assets can be justified if the research objective is to study the distribution of wealth from the perspective of the control over productive resources or the concentration of power. However, when the objective of the research is to study the inequality of welfare over the life cycle, the exclusion of public pension assets is harder to justify; pension assets provide financial security and can significantly influence behavior as people can substitute future claims with alternative forms of savings accumulation in order to face future consumption needs (Feldstein 1974). Saez and Zucman (2016) argue that “although social security matters for saving decisions, the same is true for all promises of future government transfers. Including social security wealth would thus call for including the present value of future Medicare benefits, future government education spending for one’s children, etc., net of future taxes” (p. 526). In this paper, we do not attempt to include future public pension or any other future claims from government services. Only assets held in private (defined contributions) pension plans are considered. But the debate is not settled.

The second key limitation of the SNA stems from its market valuation of asset: The cash value that can be recovered (and therefore consumed) by selling a given asset on a well-functioning market. Such a method is problematic for assets that cannot be put on sale, either because a market does not exist or because the asset itself may not be marketable. This is a valid qualification for life insurance plans, which cannot be easily accessed for liquidation. However, private reserves that insurers are required to hold for the future payment of life insurance benefits are included in the balance sheet within the class of “insurance technical reserves.” This class of assets, fully accounted for in our benchmark series, also includes the private balance of defined contribution pension plans. Moreover, the reserves held by firms for future severance payments on behalf of workers are also included.7 A similar issue arises for shares in unlisted corporations or in unincorporated private businesses taking the form of quasi-corporations, as they may never be or have never been sold.8 Financial accounts report estimated market values of unlisted shares derived from looking at similar listed corporations in the same business sector. Similarly, estimates of the market value of shares in quasi-corporations are taken from their self-reported market valuation in the SHIW (this excludes the buildings).9

Our benchmark wealth distribution series are consistent with the personal sector balance sheets. Hence, the valuation of business assets adopted in the NA also applies to our final benchmark series.

The third important limitation refers to the valuation of housing stock. In Italy, housing wealth is “estimated as the product of three factors: (a) the number of dwellings owned by households; (b) the average floor area in square meters of dwellings; (c) the average price per square meter of the dwellings owned by households. The value of housing wealth is then increased by the value of public residential properties sold to households” (Banca d’Italia 2014, p. 19). In this paper, we derive a market value measure of housing stock based on individual cadastral values reported on tax records. Our independent aggregate value of the housing stock very closely tracks the total of the household sector balance sheet and, ultimately, our distributional estimates are fully aligned with the latter.

3. From the Wealth of the Decedents to the Wealth of the Living

3.1. Inheritance Tax in Italy

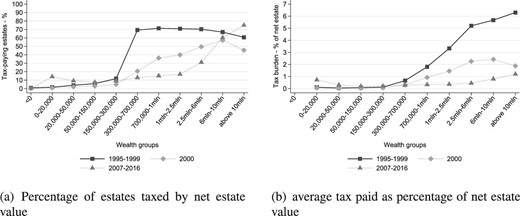

The inheritance tax (Imposta sulle successioni e donazioni) applies to all worldwide taxable assets inherited, net of liabilities and deductible expenses, from a deceased person domiciled in Italy.10 It applies to the amount received by each heir and not to the amount of total wealth left at death, as is the case for the estate taxes levied in the US or the UK. The tax rates vary depending on the degree of kinship. For spouses and direct descendants or ascendants, the rate is 4% above any net share above €1 million.11 Siblings are subject to a rate of 6% above €100,000. Relatives within the fourth degree, direct relatives in law, and side relatives in law within the third degree, are subject to a 6% rate with no exemption threshold; 8% applies to all other parties with no exemption threshold. The same rates and structure apply to inter vivos gifts.12 Until 2016, the exemption threshold was reduced by the value of the capitalized lifetime donations received by each heir from the same deceased person. This provision, known as the coacervo, aimed to limit tax avoidance through gifting by integrating the taxation of gifts and inheritance.13

Inheritance tax returns are mandatory for real estate transfers or if the estate’s net value exceeds €25,000. The tax administration is connected to the cadastral register, as other taxes apply to real estate transactions. With high homeownership rates, this ensures a coverage rate of over 50% of decedents. This remained true even during the period when the inheritance tax was abolished (2001–2006). In 2013, 365,000 estates out of 600,000 adult deaths were recorded, while 2014 data shows a record-high coverage rate of 63%. Although incomplete, a coverage rate over 60% is very high compared with the evidence from other rich countries: In the UK, this number is below 50%, whereas in the US it is lower than 0.5%.14 A variety of exemptions permit the reduction of the effective tax bill beyond the statutory description. Many assets are exempt from taxation: reserves accumulated in private pensions, life insurance funds, shares of family businesses passed to a surviving spouse or direct descendants, postal savings bonds, and government bonds. The tax-exempt status implies, in many cases, that such holdings are not reported in tax returns and need to be partially or fully imputed. The treatment of tax-exempt assets is discussed in the next section.

Three major reforms were enacted in 2000, 2001, and 2006. Before 2000, the tax was a mix between a progressive estate tax (with marginal rates ranging from 3% to 27%), and an inheritance tax (with a further graduation of marginal rates up to 33%) that applied only to recipients other than the spouse and direct relatives.15 In 2001, the inheritance and gift taxes were abolished, before being reintroduced in 2006.

3.2. The Inheritance Tax Data

Our data are sourced from the universe of inheritance tax returns filed between 1995 and 2016 (evaluated at the year of death). Executors of the estates submit the returns within 12 months of the death.16 These returns are processed by a designated official at the local tax authority branch, who assesses the tax liability. The process also involves verifying legal ownership and obtaining third-party asset valuations, which improves the accuracy of the information and minimizes opportunities for tax evasion.17

The net wealth of the decedent is obtained by adding all reported financial and real assets and subtracting all liabilities. We add to this the market value of assets sold within 6 months from death, which was reported between 1990 and 2000; this is typically negligible.

The statistical office of the Ministry of Economics and Finance transformed the microdata into detailed tabular form. The tabulations have 34 net wealth ranges, from negative values to the highest range worth €20 million or more. Accompanying demographic information is provided by seven 10-year age groups (i.e., from under 20 to over 80), two gender groups (males and females), and three geographical areas (south and islands, north, and center).18 Four asset classes are identified: housing and land; business assets, equity, and debt securities; other assets (including current and saving deposits, valuables, etc.); and liabilities and deductible expenses.19 The data, therefore, lump together all business assets (including assets from personal businesses) with financial assets. The tabulations identify the taxes paid (on the global value of the estate as well as on the inherited shares), the value of assets sold within 6 months of death (reported between 1990 and 2000), and the capitalized value of all gifts and donations made during the deceased’s lifetime.

3.3. The Application of the Mortality Multiplier Method, the Estimation of Missing Wealth, and the Treatment of Different Assets

The distribution of the taxable wealth of decedents, generated from inheritance tax data, is different from that of the wealth of the living. A number of adjustments are therefore required: differential mortality multipliers must be applied in order to transform the estate data into estimates of wealth-holding; likewise, an estimate of the wealth of those not covered by the tax (the missing wealth of the missing/non identified population), as well as that of the exempted assets, is needed; and, finally, real estate valuation must be converted from cadastral to market prices. In this section, we also discuss the estimation of personal wealth held in trusts and the valuation of business assets as well as the treatment of liabilities. A summary of the treatment of different assets in the tax records and in our benchmark series can be found in Online Appendix R.

Re-weighting the Population of the Deceased.

In 1995, 30% of Italy’s estates belonged to individuals aged 80 and above; in recent years, the number has grown to 60%. Similarly, males are over-represented across all age groups, except the oldest group. To re-weigh the decedent population, we apply mortality multipliers, obtained by inverting the mortality rates, which are therefore treated as if they were sampling rates of the living population. The application of mortality multipliers has a long tradition in economics and statistics and leads to the derivation of the identified wealth and population (for a description of the method; see Atkinson and Harrison 1978). We also use detailed annual mortality tables published by the ISTAT, available for each age, gender, and geographical location.20

The inverse of the mortality rate of each decedent group i (for which the multiplier is defined as mi ≡ 1/pi, and where pi is the mortality rate of group i) represents the number of living individuals with similar socio-demographic characteristics. We multiply the number of decedents and their reported wealth value by the relevant mortality multiplier mi for each group i.

We define the estate value of each decedent as wE,i, arranged in descending order, so that wE,i ≥ wE,j, if i < j. The population of decedents is NE and the total value of their estates is defined as WE, taking the following form: |$W_E = \sum _{i=1}^{N_E} w_{E,i}$|. The application of the mortality multiplier provides the following result: |$W = \sum _{i=1}^{N_E} m_i w_{E,i}$|, where W is the total wealth among the living population.

Given the large number of decedents covered, the re-weighting of tax records allows us to account for a substantial fraction of the living population (50%) and personal net worth (80% of NA in recent years, and 65%–70% in the mid-1990s), where this includes only the correction of the market price of housing assets. The total net wealth in the SHIW, representative of the entire population, is instead very similar to that identified from tax records between 1995 and 2006; however, from 2006, it only accounts for 65%–70% of the NA total.

The Wealth of the Missing Population.

The tax data are representative of the living adults whose wealth arrangements are such that they only come to the notice of the tax authority in the event of their death. The need to estimate the amount of missing wealth is a necessary step if we want to assess the size and distribution for the entire population. The SHIW is the basis for this. In order to be consistent with the distribution at the individual level, we first allocate household wealth to adult members of the household.21 We then estimate that 50% of adults are accounted as missing, with strong heterogeneity across age groups.22

Once the missing population and their wealth holdings are estimated, we can impute these values to the tax-based distributional information. Online Appendix H describes the very simple imputation process and shows that the estimated missing wealth amounts to €700 billion and it is mostly composed of deposits and valuables.

The Valuation of Real Estate.

To address the undervaluation of land, buildings, and dwellings for tax purposes, we adjusted cadastral values to align with market prices.23 The adjustment factor is calculated as the ratio of average market price (Osservatorio del Mercato Immobiliare—OMI, published by the Revenue Agency/Nomisma) to cadastral valuation at the national level. From 2009 to 2012, this ratio remained stable at 3.3, but declined to 3.2 in 2013, 3.0 in 2014–2015, and 2.9 in 2016. See Online Appendix E for the time series of adjustment factors.

Most notably, the simple re-scaling of property values using an annual market to cadastral value ratio generates a total housing and land stock very close to that estimated in household sector balance sheets (the average estate valued at market prices increased from €209,000 in 1995 to €332,000 in 2007 at 2016 prices; it remained relatively constant until 2012, and then started to decrease to €293,000 in 2016). Due to the structure of inheritance tax filing, as well as the prevalence of homeownership in Italy, the number of inheritance tax filers who declare real estate assets is above 90%. Similarly, the declared estate is mostly composed of real estate assets: whereas in 1995, 91% of estates were composed of housing and land, by 2016 this fraction had declined to 78%. This was also the result of the tax exemption of a number of financial assets. However, the high share of housing and land does not mean that our data are unable to capture large financial wealth holdings at the very top of the wealth distribution. Indeed, as reported in Acciari and Morelli (2022), “in 2016, only 10% of total gross estate is composed of housing and land for the group of richest 0.01% of total decedents, a group whose total declared net estate is at least €17 million. For this group, nearly 90% of total gross estate value is held in financial securities and privately held business assets. Meanwhile, for estates below the 99th percentile, housing and land account for at least 75% of total gross estate value.”

The use of a national multiplier runs the risk of masking the heterogeneity across geographical areas and, most importantly, across the wealth distribution (e.g. the degree of underestimation of real estate market values could be more pronounced for rich individuals). To address this concern, we run a number of checks matching the full cadastral records of over 34 million properties to the corresponding OMI market value of the area, as well as to the income tax statistics for over 32 million tax payers (the OMI market value is the average market price of the micro-zone where the real estate is situated). Checks are also carried out by integrating the EU-SILC survey with administrative data from the cadastre and OMI market value data (carried out internally at the Ministry of Economy and Finance through a microsimulation model). These exercises are detailed in Online Appendix E.2. Our main findings suggest that although the full heterogeneity across locations and rankings in the income distribution is ignored, the use of a national multiplier should only marginally affect estimates of wealth concentration. Our results are likely to represent conservative estimates, as controlling for the heterogeneity discussed above would have likely increased the level of wealth concentration even further, albeit marginally.

Tax-Exempt Assets.

Italian legislation grants full exemption to financial assets invested as private pension and life insurance, postal saving bonds (i.e., Buoni Fruttiferi Postali), and a number of national and extra-national government securities.24 The list of exempted assets also includes vehicles on the national registry, credits toward the state, properties that are listed as cultural and historical heritage, and family businesses and control shares of private businesses that are transferred to direct descendants or to a spouse.25 The value of tax-exempt assets considered here, imputed to the population, is taken from the household sector balance sheet as the value of insurance technical reserves net of their liabilities (i.e., the value of assets accumulated in pension, life insurance, and severance payment funds), plus 50% of Italian government securities; they amounted to €320 billion in 1995 and €940 billion in 2016, equivalent to 11% of household net wealth (see Online Appendix H.2). The reporting of government bonds is often advised by tax accountants and frequently occurs in those cases where securities are bundled together with other assets within investment funds (e.g. banks and other financial intermediaries are required to provide detailed descriptions of investment funds and accounts following the death of a legal owner). Such investment bundles can be fully reported on the inheritance tax form, so that the tax authority could then compute the relevant tax deductions.26

Business Shares and Equities.

The total value of business assets held by households is composed of the sum of the shares in corporations and quasi-corporations. Our tabulations bundle business assets with other financial assets such as mutual fund shares and bonds. The final valuation of business assets adopted in our benchmark distribution series is consistent with personal sector balance sheets. Hence, shares in corporations and quasi-corporations are included at market value. To do so, the value of any “shares and other equities” as an asset of the household sector balance sheets that is not accounted for in our inheritance tax-based data is distributed to the whole adult population as a proportion of the total “financial assets” across each age, gender, and location cell. Note that this method also applies as we distribute the value of plant, machinery, equipment, inventories, and goodwill of small personal businesses of producer households. Differently from shares in corporations and quasi-corporations, these are real assets listed as “fixed capital” in the balance sheet, and are valued at substitution price net of depreciation. See Online Appendix A.4 for an account of business assets in the macroeconomic accounts.

Trusts.

Trusts are not taxable under the inheritance tax, as the property of the settled assets is transferred from settlors to trustees. Very little is known about the amount of wealth held in trusts in Italy, but their use is not as widespread as in the US or the UK. According to data from the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the number of trusts operating in Italy required to file a tax record increased from 65 in 2009 to 151 in 2019 (14 of which were foreign trusts). Using the universe of income tax files allows us to observe the capital incomes from trusts (national and foreign) that are imputed to individual resident beneficiaries (transparent trusts), as well as those that are retained in opaque trusts (Redditi da capitale imputati ai trusts). On average, 89% of the capital incomes of trusts are reported to be distributed to beneficiaries. We capitalize those capital income flows to arrive at a value of €166–332 million for 2015 and €263–526 million for 2019.27 In 2016, these wealth value estimates only accounted for 0.002%–0.005% of wealth (see Online Appendix Q). These values almost certainly represent a lower bound, as capital incomes are often subject to separate withholding taxes and may be under-reported in Italian income tax records. Yet even doubling the estimates of total wealth held in trusts would not change the fact that such assets would only have a negligible effect on the distribution of personal wealth, even if they were imputed entirely to the wealthiest groups.

Liabilities.

The concept of net worth used in this paper subtracts all liabilities from real and financial assets. The existence of very high tax exempt thresholds reduces the incentive for detailed reporting of liabilities for most (non-taxable) estates. To overcome this limitation, in our benchmark series, the unobserved value of liabilities reported in the national balance sheets is imputed proportionally to the population according to the distribution of liabilities reconstructed from the tax data, complemented with observations about the missing population, using the survey data as described above.

A less relevant limitation of tax records comes from the fact that liabilities may be reported together with deductible expenses, which include the costs of a funeral or medical treatments during the last 6 months of the deceased person’s life. While it is not possible to appropriately add the deductible expenses back to the value of the individual estate, the entity of these expenses is negligible (e.g. only a small fixed amount of funeral costs that can be deducted for tax reasons but no specific threshold is specified for health related costs).

3.4. Combining Different Sources of Data

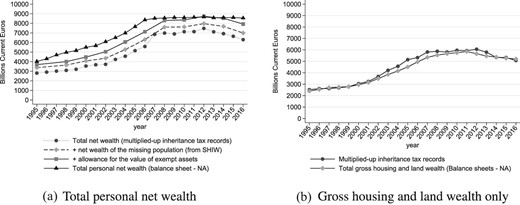

The process of adding the wealth of the identified population (including the price adjustment to real estate), the wealth of the missing population, and the imputation of exempted assets, shown in Figure 3, generates a total wealth that is between 80% and 100% of the balance sheet of the household sector in the NA, with very similar trends.

Total personal net wealth and total gross housing and land wealth: from inheritance tax records to NA. Panel (a) compares the different wealth aggregates, from that identified using the estate multiplier method (scaling-up the reported wealth at death), with the total net wealth of the household sector from the national balance sheets. Panel (b) compares the total gross value of the housing and land stock as identified from the inheritance tax records with that reconstructed from the balance sheet of the household sector from the NA.

In seeking to align the benchmark series to the NA, the remaining gap of total assets and liabilities must be imputed. This benchmark approach is justified on the grounds that the NA provide a reasonable indicator of the development of wealth over time, preserving a high degree of cross-country comparability, rather than on the assumption that the NA give the correct numbers. On the one hand, the imputation of the wealth gap is a controversial exercise, riddled with difficulties and uncertainty. On the other hand, the adjustment to NA is advantageous in that it deals indirectly with any residual misreporting, mis-valuation, or tax avoidance and evasion ignored in the preceding steps. In any case, it should be stressed that some of the difference between NA and other wealth data sources are rooted in definitional issues rather than quantitative misalignment.

For all these reasons, we will also discuss the variety of ways in which estimates behave once we deviate from the benchmark (e.g., excluding imputations). This type of exercise has not commonly been reported in previous studies of wealth inequality; however, we argue that it is essential to increase transparency about how final measures of concentrations are derived, and should not be relegated to a marginal appendix.

4. The Growing Inequality of Wealth Holdings

4.1. Benchmark Series

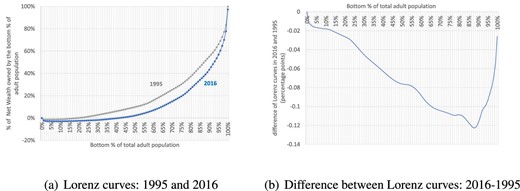

Similarly to using household surveys, one of the immediate advantages of our benchmark approach over the strict application of the estate or the capitalization methods is the potential to analyze the size distribution for the whole population. We can show how the shape of the wealth distribution has changed over time. As illustrated in panel (a) of Figure 4, the Lorenz curve shifted outward from 1995 to 2016. Panel (b) plots the difference between these two curves over time. The difference is always negative for every wealth group, as the Lorenz curve in 2016 always lies below that of 1995. Therefore, any possible standard indicator would point in the same direction: Wealth inequality has increased in Italy over the time period considered.28

Increasing wealth inequality over time. Panel (a) compares the Lorenz curves in 1995 and 2016. Panel (b) shows the difference between these two Lorenz curves.

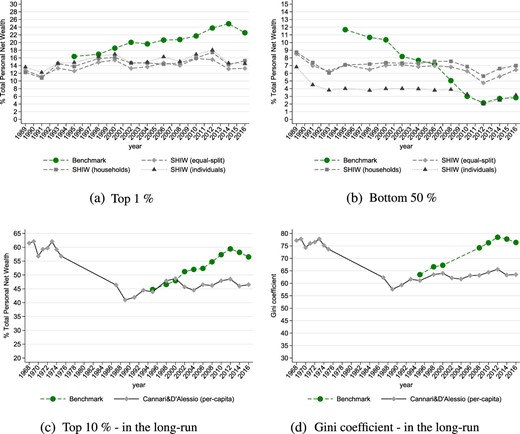

We illustrate this point with the evolution of the Gini coefficient, which recorded a 14 percentage point increase, from 62% in 1995 to 76% in 2016 (see Online Appendix A.2). This is a substantial change if compared with results from SHIW data (Figure 7).

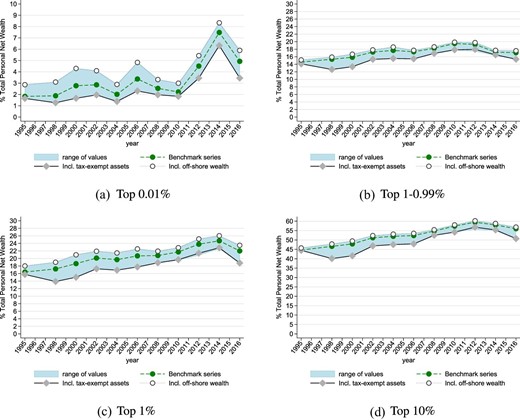

We now zoom in on the upper wealth brackets. The top 1% (adults with at least €1.5 million and average net wealth holdings of €3.8 million) controlled about 22% of net wealth in 2016, a share that has increased by 6 percentage points since 1995 (Figure 5). Panels (a) and (b) of Figure 5 also demonstrate the importance of looking within the top 1%, as top groups are highly heterogeneous. The share of the top 0.01% more than doubled between 1995 and 2016, increasing from 1.8% to 5%. Such a tiny group held 500 times their proportionate share in 2016, with a minimum net worth of €20 million and average net worth of €83 million, equivalent to 470 times the average net worth. The share of the top 1% excluding the top 0.01% rose gradually from 1995 to 2012, increasing from 14.4% to 19.0%, before declining again and stabilizing around 17%.

The evolution of top wealth shares. Italy 1995–2016. The graphs show the evolution of the shares of total personal net wealth for four subgroups of the adult population between 1995 and 2016. Each panel shows three series. The middle line is the benchmark (distribution of balance sheets). The upper line, after adjustment to NA, also includes unreported offshore financial assets. The lower line, instead, only allows for tax exempt assets.

The ranges of values depicted in the figures (which are not confidence intervals in the statistical sense) signal that the adjustments required to reach the benchmark series are not the only ones that can be adopted. Yet the estimated wealth concentration and its evolution remain robust regardless of the inclusion or exclusion of our adjustments to the data. The bottom of the range is derived by imputing only tax exempt assets: falling short of fully imputing all missing assets and liabilities required to align distributional estimates to the household balance sheet as shown in our benchmark case. The upper limit, instead, imputes even more assets than our benchmark case by also including unreported financial assets held in offshore tax havens.

Unreported Offshore Wealth.

A fraction of financial wealth remains unreported or unrecorded in official statistics and tax agencies. Zucman (2013) argues that this represents 10% of world GDP. Applying similar methods, Pellegrini, Sanelli, and Tosti (2016) estimated undeclared debt and equity securities in Italy to be €161.4 billion in 2007, excluding undeclared bank deposits. Figures on undeclared bank deposits held by the non-banking sector in offshore centers are also reported in Pellegrini, Sanelli, and Tosti (2016), based on the cross-border banking statistics released by the Bank of International Settlements. We assume that half of the latter belongs to individuals, and from this allocate to Italy the country’s share of global GDP.29 The resulting estimate of unreported financial wealth held offshore by Italian investors is €187.2 billion in 2007, or some 2%–3% of personal wealth.30 We further extrapolate backward and forward according to the evolution of the European offshore financial wealth given in Alstadsæter, Johannesen, and Zucman (2018), to cover the period 1995–2016.

If we assume that the share of undeclared wealth and its relative distribution across the wealth distribution in Italy is the same as what was estimated for Denmark and Norway by Alstadsæter, Johannesen, and Zucman (2019), then the share held by the top 1% increases by 1–2 percentage points throughout. This is a significant effect that becomes even more visible at the very top. The richest 0.001% of individuals saw their share increase by 65% in 1995 (from 1.8% to 3%) and by 14% in 2016 (from 5% to 6%). The inclusion of unreported offshore financial wealth is surrounded by much uncertainty; however, it does not appear to substantially affect the trend of the concentration over the period studied.

4.2. Comparison with other Countries

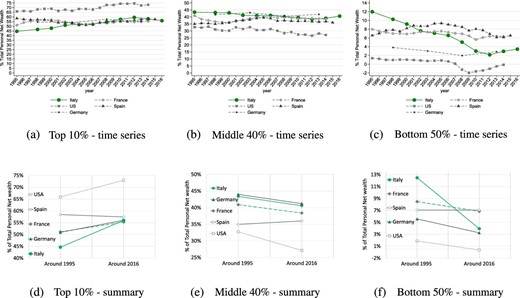

Our benchmark series are currently comparable with the wealth concentration estimates available for France, Germany, Spain, and the US (the comparison with existing country series that do not follow the strategy of up-scaling to the NA is given in Figure 16(b)). Figure 6 displays three concentration indicators: the top 10%, the bottom 50%, and the middle 40%. Italy, in the mid-1990s, had one of the (relatively) best-positioned middle 40% groups, and one of the lowest concentration levels. Similarly, the bottom 50% held 12% of wealth in 1995 compared with 8% in France, 7% in Spain, 5% in Germany, and 1% in the US. Twenty years later, Italy appears to have experienced the largest drop in total wealth held by the bottom 50%, and, although the levels of wealth concentration are now closer to those of other European countries, its relative increase over time bears more similarity to the dynamics of the US. However, the middle 40% in Italy controls 40% of total net wealth compared to 30% in the US.

Wealth concentration: a cross-country comparison. The figure compares the evolution of wealth inequality from c.1995 to c.2016 for countries for which we have series comparable to our benchmark. Italy is based on the authors’ results, Spain comes from Martínez-Toledano 2017, France from Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret, and Piketty 2021, Germany from Albers, Bartels, and Schularick 2020, and the US from Saez and Zucman 2016. “Around 1995” refers to 1995 for all countries except Germany (for which it refers to 1993). “Around 2016” refers to 2014 for France and the US, to 2015 for Spain, to 2016 for Italy, and to 2018 for Germany.

The notable decline in the share of the bottom 50% may seem surprising from the perspective of the given international comparison. However, it is consistent with the sizeable increase in Italy’s aggregate wealth and with the fact that this group has not benefited proportionally from the factors pushing average wealth upwards: They own zero-return financial assets, have very little net real estate, or are heavily indebted mortgage-wise.

5. Triangulation with other Sources

We now consider external evidence based on a variety of sources, from household surveys to rich lists and banking sector reports.

Household Survey: Evidence from SHIW Data.

Data from SHIW provide essential information about the distribution of Italian households’ wealth since 1989. A comparison with tax data requires changing the unit of analysis from households to individuals. Household wealth must be allocated to each adult member using the relevant information from the survey questionnaire, as done in D’Alessio (2018) and mentioned in Section 3.3. Furthermore, to bring the estimate in line with our concept of wealth, an estimate of private insurance funds and pension assets are added to individuals declaring payments of any insurance premium or private pension contribution. As shown in Figure 7, moving from the household to the individual reduces the share of the bottom 50% by 5 percentage points (panel (b)), a large change, and increases the share of the top 1% by 2 percentage points (panel (a)). The concentration at the top is only marginally different if we split household wealth equally among the head of the household and his or her partner (equal-split series).

Gini coefficient, Top 1%, and Bottom 50% shares in total wealth: comparing results with household survey data. Panels (a) and (b) show the evolution of the top 1% and bottom 50% shares from household surveys (SHIW) compared with our benchmark series. The comparison requires adjusting the wealth concept and the unit of analysis (from households to individuals). Panel (c) compares the evolution of our benchmark series of the top 10% with that from Cannari and D’Alessio (2018b) based on the combination of the SHIW and historical surveys from 1968 to 1975.

The levels and dynamics of wealth concentration are very similar across tax- and survey-based estimates until 2000, when they begin to diverge. According to the SHIW, the top 1% share remained roughly constant between 1995 and 2016, however, according to our benchmark, it increased by 6 percentage points (Figure 7(a)). On the contrary, as shown in Figure 7(b), the share held by the bottom 50% is substantially higher in our benchmark series until 2004. The share of the bottom 50% becomes almost identical in both sources only from the mid-2000s onwards.

Different explanations can rationalize these complex findings. The under-representation of the wealth concentration at the top is not surprising. For a variety of reasons, household surveys are not necessarily well-suited to capturing the right tail of a highly skewed wealth distribution. First, in the presence of “fat tails,” such as the distribution of wealth, a random sample may not be fully representative of all wealth groups, especially if the sampling frame of the survey does not allow for the oversampling of wealthy households, as is the case for the SHIW. Second, even if very wealthy households were appropriately sampled, they might have a higher rate of nonresponse, as they may be harder to find or trace, or they might be less willing to cooperate to reveal their complex asset portfolios. The compliance rate may well be lower at the top of the wealth distribution, distorting the estimation of inequality indicators (Korinek, Mistiaen, and Ravallion 2007; Kennickell 2019; Muñoz and Morelli 2020). Indeed, the SHIW identifies fewer people and less wealth for the wealthiest ranges of the distribution compared with our multiplied-up estates from inheritance tax records (more details in Online Appendix F).31

Nonetheless, total personal wealth in the survey data amounts to 60%–70% of the balance sheets despite its implicit coverage of the total population (see Figure G.2 panels (a) and (c) in the Online Appendix). This indicates that underreporting of different types of assets and liabilities, as well as coverage issues, may also apply to the middle and bottom ranges of the distribution. The fact that the bottom 50% of the distribution appears so different in the survey data compared with our benchmark results may also indicate the inability of the survey to appropriately account for the most important form of assets for the lower groups, namely currency, deposits, and valuables. In our derived benchmark series, these assets constitute over 50% of the wealth of individuals with less than €15,000, that is, a substantial part of the bottom 50%. This stresses the need for better data to assess low-end segments of the wealth distribution, not just the high-end, as generally noted. The total value of currency, deposits, and bonds reported in the survey data was lower than that of NA-based data by a factor of 3.5. By 2004, the share of currency, deposits, and bonds stabilized at 20% of total net wealth in the balance sheet, by which point the survey underestimated the total NA value by 2.7 times. By 1995, however, the value of currency, deposits, and bonds accounted for 32% of total gross personal wealth in the balance sheet and the relative importance of this asset class declined, accounting for only 18% of total gross personal wealth in 2016.

More generally, the aggregate coverage rate of assets in the survey data, with respect to the NA statistics, is highly heterogeneous across asset types, ranging from 30% for liabilities and 35% for financial assets, to 85% for housing assets. The trend of these asset coverage rates has also changed over time: whereas little change occurred for housing assets, the coverage rate for financial assets and liabilities has been steadily declining over time. Figure G.2 (panels (b) and (d)) as well as Table H.1 in the Online Appendix document these patterns providing a more detailed decomposition of asset types.

Rich Lists and Banking Sector Reports.

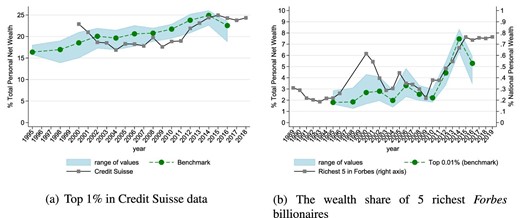

Forbes magazine gives information on Italian billionaires; only 5 individuals were recorded in 1988, and 35 in 2019. The data are often based on journalistic estimates that can be subject to several types of errors, and the methodology used cannot be evaluated. According to Vermeulen (2017), parametrically adjusting the SHIW with the extreme observations from the rich list increases the top 1% share by 6–7 percentage points from a level of 14% in 2010. Applying similar methods and data from the Forbes World’s Billionaires, Davies, Lluberas, and Shorrocks (2017) imputed the “missing” upper-end of the wealth tail to household survey data for several countries from 2000. The same exercise is also carried out, on an annual basis, for the Global Wealth Report by Credit Suisse; their estimates from the mid-2000s appear to be in line with our benchmark series. Figure 8(a) shows this for the top 1%. These hybrid estimates seem to suggest that the correction of survey data for missing wealth, especially in the upper end wealth bracket, may prove a fruitful avenue for future research.

Triangulation of the evidence with external data series. Panel (a) compares the top 1% share of wealth from our benchmark series, from the Credit Suisse Report (combining SHIW data and Forbes rich list). Panel (b) compares the top 0.01% share of wealth from our benchmark series with that of the five richest individuals listed in the USD global billionaires rich list by Forbes.

We can track the share of total net wealth held by the Forbes richest five or ten individuals, from 1988 and 2000, respectively. As shown in Figure 8(b), a group whose size is a thousand times bigger (the top 0.01% represents 5,000 individuals) holds a share ten times higher. The dynamics of the Forbes list broadly concurs with our benchmark series. The five wealthiest Italians almost tripled their share of total wealth from the mid-1990s to 2016, from 0.2% to 0.7% (and the share remained at a similar level until 2019). The share of the top 0.01% also rose, from 2% to 7%.

6. Determinants of Wealth Concentration

Precisely identifying the channels that affect the evolution of wealth inequality has important implications for policy; however, the question remains broadly unanswered. Recent work in the US has emphasized that wealth inequality can be fueled by differential saving rates coupled with increasing income inequality (Saez and Zucman 2016). As discussed in Fagereng et al. (2019), richer households mostly “save by holding [...], meaning that they tend to hold on to assets experiencing persistent capital gains.” Indeed, a growing body of evidence stresses the importance of the heterogeneity of portfolio composition, asset prices, and rates of return across the wealth distribution (Alvaredo, Atkinson, and Morelli 2018; Fagereng et al. 2020; Benhabib, Bisin, and Luo 2017; Kuhn, Schularick, and Steins 2020; Advani, Bangham, and Leslie 2020; Martínez-Toledano 2020). Beyond these factors, individuals also differ in the extent of wealth transfers received via gifts and inheritances, as stressed in Feiveson and Sabelhaus (2018). It has also been suggested that the receipt of large inheritances may have a dis-equalizing effect, especially in the long-run (Nekoei and Seim 2018; Nolan et al. 2020). Reality is complex and certainly involves all the aforementioned elements, as well as others. For instance, Hubmer, Krusell, and Smith (2020) highlight how the decline of the progressivity of income taxes could explain the most important part of the dynamics of US wealth concentration since the 1980s. Other macroeconomic factors may well be very important too. Indeed, the period under analysis here is one of substantial economic turbulence, in which structural reforms to the Italian economy significantly affected the labor and credit markets, the public pension system, and a widespread program of privatization of state-owned corporations. As argued in Brandolini et al. (2018) “the currency crisis of 1992 is a watershed in Italy’s economic development. It marks the start of a phase of weak economic performance and uncertain growth prospects.” There are also concerns about the impact of the large Central Banks’ programmes of long-term bonds purchases, pursued in the US, the UK, and the EU following the Great Recession (Franconi and Rella 2023). To address these issues, this section explores some of the potential determinants of the trend of wealth concentration in Italy.

6.1. The Portfolio Composition across the Wealth Distribution and Wealth Dynamics

Workers save out of earned incomes during their working lives in order to dis-save through retirement and to face any other expected or unexpected needs throughout their life cycle. Moreover, for any given age group, different people across the income and wealth distributions may have different saving rates. Beyond this (obvious) accumulation channel, the existing stock of real and financial assets tends to reproduce itself; financial and real estate wealth may be invested, generating income returns that can be saved in turn. Positive real interest rates may accrue on bank accounts, and assets may also appreciate or depreciate over time, implying changes in the valuation of the stock of wealth independent of individual decisions to save.

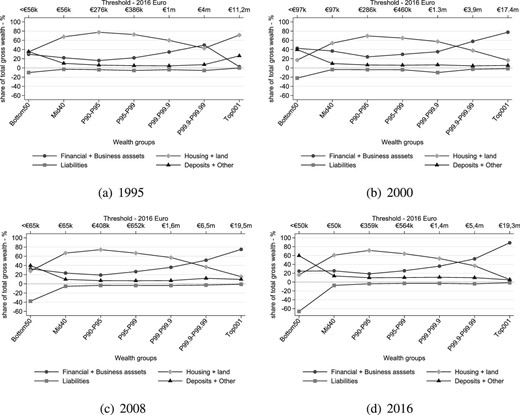

The relative strength of each channel can vary over time and apply differently to different segments of the distribution. For example, Italy has experienced a marked decline in households’ savings rates out of disposable income since the mid-1990s, dropping from 16% in 1995 to 3% in 2016. During the same period, the interest rates on deposits decreased from 5.6% to 0.4%. Given that deposits make up a significant portion of total wealth for the bottom 50% group (along with valuables, amounting to at least 50% of gross wealth, Figure 9 in Online Appendix N.4), it is reasonable to expect a strong co-movement between the decline in saving rates and returns on savings and the wealth share of this group.

Additionally, the middle 40% and the top 10%–5% are likely to be particularly influenced by the dynamics of the real estate market because housing and land constitute the largest asset class for them (60% of total gross wealth in recent years as documented in Online Appendices Figure N.3(b) and N.3(c)). Between 1995 and 2008, the OECD house price index in Italy increased by 35%, closely following the growth in the average net wealth held by the middle 40%. However, after the 2008–2009 financial crisis, house prices stagnated and then declined, with the average house price decreasing by 27% by 2016. Between 2008 and 2016, the real average net wealth of the middle 40% declined by 12%.

Conversely, financial securities and corporate and non-corporate personal business assets have become dominant in the portfolios of the wealthy, particularly in recent years. In 2016, individuals with more than €20 million (the top 0.01%) held more than 80% of their wealth in the form of financial and business assets (see Figure 9). Hence, the reversal of house prices since the 2008 crisis, coupled with a fast rebound of stock prices, may have contributed to the substantial rise in wealth concentration at the top that we observe since 2010. Indeed, the OECD share price index for Italy declined by 59% between 2007 and 2012 and rebounded by 50% by 2015, before dropping again by 15% in 2016.

The composition of wealth across the wealth distribution. Adults are ranked by net wealth. Bottom, middle, and high-end groups are identified and total net wealth is decomposed into four classes: housing and land; business assets, equity, and debt securities; deposits and other assets (including cash, valuables, etc.); and liabilities. The top x-axis in each panel of the graph represents the monetary threshold (in 2016 Euro) to belong to each group. See Table N.1 in the Online Appendix for more details.

To further probe the role of heterogeneous portfolios and their returns, we use our data to show how different asset classes contributed to the rise in the concentration of wealth. For each group i, we define the share in total net wealth as Si, which in turn can be written as the weighted average of the housing (H) wealth share and the non-housing (NH) wealth share of the same group i. As discussed in detail in Online Appendix N.1, the exercise reveals (see also Figure N.1) that wealthy individuals have been capturing a growing share of non-housing wealth.

6.2. Decomposing Wealth Growth by Wealth Groups and Asset Types: The Role of Savings, Indebtedness, and Capital Gains

To better understand the proportional contribution of each asset class to the wealth growth of each wealth group P, we consider net wealth NW as the sum of each asset class Aj, housing and land (H), business and financial assets (F), and deposits and valuables (Dep), net of total indebtedness (D).

Following the work by Albers, Bartels, and Schularick (2020), we identify the contribution of each asset class to total wealth growth, over 1995–2016, by totally differentiating equation (1) and dividing by |${\it NW}^{P}_{t}$|.

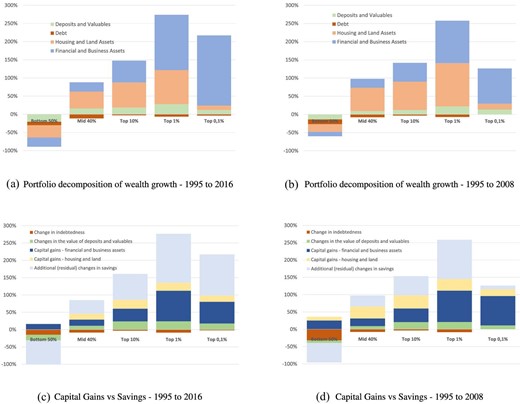

Differently from Albers, Bartels, and Schularick (2020), we explicitly consider the composition of net wealth growth, and in doing so are able to isolate the contribution of indebtedness too. Online Appendix Table N.2 and Figure 10(a) and (b) highlight the heterogeneity of the results by wealth groups.

Between 1995 and 2016, housing wealth contributed 67% to the overall gross wealth growth. The relative contribution remains close to 60% for the middle 40%; however, it declines to 50% for the top decile, to 35% for the top 1%, and to 9% for the top 0.1%. On the contrary, the role of financial and business assets becomes much more prominent within the top percentile: It accounts for 57% and 85% of the growth of net wealth for the top 1% and the top 0.1 %, respectively (see Online Appendix N.2). Things are very different for the bottom 50% group, which lost 90% of its net wealth over 1995–2016, and for which declining values of currency and deposits and increasing levels of indebtedness account for a third of its net wealth change.

The Role of Savings and Capital Gains.

To further document the distinctive roles of the change in the volume of savings from that of the change in the price of assets, one needs only a simple law of motion of net wealth for each group P at time t, |${\it NW}^{P}_{t}$|:

where |${\it NW}^{P}_{t}=W^{P}_{t} - D^{P}_{t}$|, |$W^{P}_{t}$| is total gross wealth, |$D^{P}_{t}$| is the level of debt, |$\tilde{S^{P}_{t}}$| is total savings in period t net of all changes in indebtedness level for the group P, and |$q^{P}_{t}$| is the weighted average of price changes of asset j weighted by the average portfolio share of each asset j for wealth group P.

We then make use of the four components of net wealth available in our database, H, F, Dep, and D, assuming that all changes in the latter two classes are only the result of changes in volumes (savings), rather than in prices. Hence, only price changes for housing and land (|$q^{HP}_{t}$|) and for financial and business assets |$q^{FP}_{t}$| matter to our estimation if the role of capital gains. The accumulation equation can be rewritten as follows:

If one estimates the components associated with capital gains from housing and financial assets, changes in the indebtedness levels, |$\Delta {D^{P}_{t}}$|, and changes in direct savings under the form of deposits and valuables, |$\Delta {Dep^{P}_{t}}$|, one can define the residual change that reconciles the change in the wealth of group P. This residual category is defined as residual savings, |$RS^{P}_{t}$|, and we can interpret this variable as the variation in wealth resulting from changes in the volumes of housing and financial assets.

In line with existing literature (Saez and Zucman 2016; Kuhn, Schularick, and Steins 2020; Albers, Bartels, and Schularick 2020), the resulting savings flows would be considered “synthetic” as they are derived under the assumption of no mobility of individuals across wealth groups.

This exercise requires information about changes in prices. Following work by Albers, Bartels, and Schularick (2020), we use the observed portfolio composition of each wealth group P, and the OECD cumulative changes in the share price index and the house price index.32 We repeat this exercise over four different sub-periods: 1995–2000, 2000–2008, 2008–2012, and 2012–2016.33 This allows us to decompose the cumulative wealth growth across wealth groups during the whole period, between 1995 and 2016, and between 1995 and 2008, right before the onset of the financial recession.

Results are presented in Table N.3 and Figure 10(c) and (d) for the bottom 50%, the middle 40%, and the top 10%. To illustrate further heterogeneity, the top 1%, and the top 0.1% are also shown. Two main sets of findings are worth highlighting.

First, relatively little of the change in wealth recorded between 1995 and 2016 can be attributed to changes in house prices. This is due to the fact that house prices rose substantially until 2008 and then declined, meaning that the cumulative capital gains of the period were very small. The role of capital gains of housing assets becomes more prominent if we restrict the analysis to the upper middle class (middle 40%) and to the sub-period preceding the great financial recession. On the contrary, the total wealth of the top 1% increased by more than 250% from 1995 to 2008, with 36% of this growth attributable to changes in the price of financial and business assets. The percentage grows to 44% for the top 0.1% group.

The second main set of results follows. Our analysis suggests that changes in net wealth are predominantly driven by volumes and not by changes in the prices of financial and real assets. The bottom 50% group experienced a 90% decline in net wealth between 1995 and 2016. For this group, increasing indebtedness and, most importantly, declining deposits and volumes of housing and financial assets account for the bulk of overall change in wealth. At the very top, the net wealth of the top 0.1% grew by almost 300% over the same period, with over 75% of such growth being driven by changes in the volume of real and financial assets, as well as increases in deposits and valuable assets. Restricting the analysis to the period preceding the onset of the great financial recession highlights the more significant role of capital gains, especially at the top of the distribution.

It is worth noting that the use of external share and housing price indexes to derive “synthetic saving rates” for different wealth groups does not preserve the consistency with the NA framework. Also, diverging from Mian et al. (2020) and Bauluz, Novokmet, and Schularick (2022), we made no allowance for corporate retained earnings in our definition of savings. We discuss these methodological choices in Online Appendix N.2.

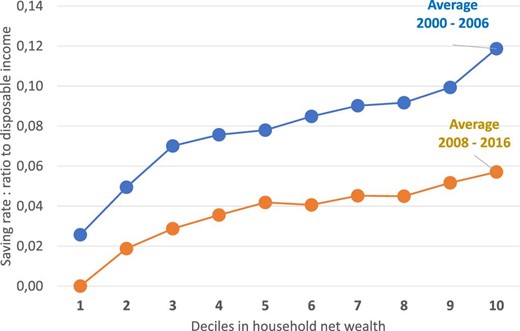

Interestingly, changes in the volumes of assets and savings continue to play an important role even with no allowance for corporate retained earnings, including at the top of the distribution. Moreover, the role of changes in the volume of assets remains strong despite a sustained trend of the saving capacity of Italian households declining over recent decades. Whereas the household saving rate as a percentage of disposable household income was one of the highest in the world in 1995 (16%); it declined to moderate levels at 3.2% in 2016. Using the SHIW, we estimated the gradient of household saving rates (defined as the difference between disposable income and consumption as a proportion of disposable income) with respect to the ranking of household along the net wealth distribution. We preserved this gradient but adjusted the estimated levels of saving rates to account for the proportional difference between the aggregate saving rates estimated in survey data and OECD macroeconomic statistics. The results averaged out for the 2000–2006 and 2008–2016 periods are presented in Figure 11 and show no evidence for a growing degree of dispersion of saving rates by wealth levels. Saving rates were more than halved for every net wealth decile from 2000–2006 to 2008–2016. The savings rates of the richest decile was 12% on average between 2000 and 2006, 10 percentage points higher than that of the bottom decile. Over the 2008–2016, the saving rate of the top decile was halved to 6%, whereas the average saving rate of the bottom decile turned slightly negative.

Heterogeneity of saving rates across household wealth groups. The figure shows saving rates by wealth levels estimated from SHIW. The saving rate is defined as the difference between disposable income and consumption as a proportion of disposable income. Saving rates are then re-scaled to account for the proportional difference between the aggregate saving rates estimated in survey data and OECD macroeconomic statistics.

The Joint Distribution of Income and Wealth.

We further investigate whether a growing share of labor or capital incomes is concentrating in the hands of wealthy individuals, and examine the joint distribution of income and wealth to assess the extent to which top wealth holders are also top labor and top capital income earners.

In order to derive the share of total labor income accruing at the top of the wealth distribution, we have linked, at the level of the individual, income from tax data in the year before death to net wealth at death.34 We have repeated this exercise with the wealth observed in 2014, which represents the peak of concentration, and on the wealth observed in 2001, the last year before the temporary elimination of the inheritance tax. Personal Income tax records were analyzed in 2013 and 2000, respectively. We have then built aggregated data matrices, with joint distribution of wealth and labor income for different age groups and genders.

We define labor income as the sum of employment income and self-employment income. We define self-employed income as the sum of professional income, income from sole proprietorship and partnerships. For these categories, it should be taken into account that a part of income is generated from labor, while the remaining part is generated from capital. Capital income is instead defined as the sum of financial capital income (including realized capital gains), lands and buildings income, and residual business income, which we assume are not attributable to labor. However, it is worth noting that some forms of financial income are taxed at source, so they are not captured in personal income tax returns. A precise definition of these income categories can be found in Online Appendix N.2.

In Online Appendix Figure N.2, we show the share of capital income and labor income accruing to the top 1% of the wealth distribution. The concentration of capital income is much greater than the concentration of labor income and even greater than the concentration of personal wealth. However, the dynamics of concentration over time appear relatively stable between 2001 and 2014. While the labor income share for the top 1% of the wealth distribution declined slightly from 2.82% to 2.29%, the share of capital income also increased slightly from 15.5% to 16.1% and does not mimic the sustained rise in wealth concentration at the top. The overall dynamics of top fiscal income shares are mostly driven by what happens to labor income, which accounts for 55% of total reported fiscal income, whereas capital income only accounts for 5% of the total. A similar exercise carried out for France by Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret, and Piketty (2021) shows that the labor income share of wealthy individuals declined substantially over the course of the long run from 1970 onward, moving in the opposite direction to the share of capital income accruing to the top of the wealth distribution. More in line with our evidence, Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret, and Piketty (2021) show much milder dynamics of income shares from 2000 onwards.

We further estimate the probability for top labor earners to belong to the top percentile of the personal wealth distribution. We repeated the exercise for the top 1% and top 0.1% of labor income earners (who reported at least €90,000 and €200,000), and found that between 2001 and 2014 such probability doubled for both groups. It increased from 7.8% to 15.5% for the richest 1% labor income earners and from 20.5% to 54.3% for the top 0.1%. Levels in recent years are similar to what is observed in France (Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret, and Piketty 2021). However, the estimated trend appears to be moving in the opposite direction: In France, the probability of top 1% of labor earners to belong to the top 1% of wealth holders is declining slightly, from 20% in 2000 to 17% in 2012, a negative trend that is much more pronounced if compared with available estimates in 1970, 29%.

On the one hand, the results may indicate that upper wealth ranges may open the doors to top earning positions. On the other hand, consistent with the evidence about raising top income shares over the past decades (Alvaredo and Pisano 2010 and Guzzardi et al. 2022), results may indicate that Italian top labor earners have increasingly higher chances to climb the wealth ladder to the very top (via either higher savings or higher returns to wealth).

However, as remarked in Brandolini et al. (2018), it is important to recall that widening inequalities must be seen in the context of a peculiar macroeconomic setting in which “Italy is the only major advanced country which, in the last two decades, suffered a fall in real household incomes per capita” (p. 5). The documented growing probability for top earners to be at the top of the wealth distribution might therefore have an alternative interpretation: Individuals in the bottom and middle ranks of the income distribution might find it increasingly difficult to climb the wealth ladder. Raising the wealth-to-income ratio (as documented in the introduction) may reflect this growing relative “unaffordability” of wealth for average income earners.

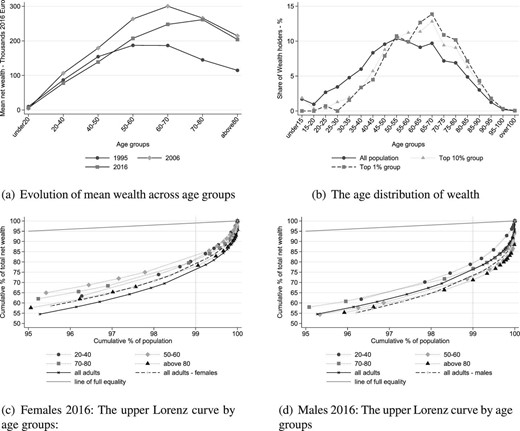

6.3. The Evolution of Wealth over the Life Cycle

The concentration estimates discussed so far refer to snapshots of the distribution in given years and include wealth and savings accumulated for life cycle purposes. As written in Cowell and Van Kerm (2015), “even if everyone had common wealth accumulation paths over the life cycle, wealth at any point in time would turn out to be unequally distributed when pooling observations of individuals of different age.” Indeed, average wealth does vary considerably across the age distribution; older generations are much richer, as one would expect. In 1995, average wealth peaked at 40–50 years but was less than a third of this amount for the 20–40 age group. Average wealth increased for all ages until 2007 before receding following the Great Recession, in particular for younger groups (Figure 12(a)). However, assessing the average wealth holding between age groups does not sufficiently capture the role of age in determining the extent of wealth concentration.

The life-cycle dimension of wealth distribution and inequality.