-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

John W. Funder, Robert M. Carey, Carlos Fardella, Celso E. Gomez-Sanchez, Franco Mantero, Michael Stowasser, William F. Young, Victor M. Montori, Case Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Patients with Primary Aldosteronism: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 93, Issue 9, 1 September 2008, Pages 3266–3281, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-0104

Close - Share Icon Share

Objective: Our objective was to develop clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with primary aldosteronism.

Participants: The Task Force comprised a chair, selected by the Clinical Guidelines Subcommittee (CGS) of The Endocrine Society, six additional experts, one methodologist, and a medical writer. The Task Force received no corporate funding or remuneration.

Evidence: Systematic reviews of available evidence were used to formulate the key treatment and prevention recommendations. We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) group criteria to describe both the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations. We used “recommend” for strong recommendations and “suggest” for weak recommendations.

Consensus Process: Consensus was guided by systematic reviews of evidence and discussions during one group meeting, several conference calls, and multiple e-mail communications. The drafts prepared by the task force with the help of a medical writer were reviewed successively by The Endocrine Society’s CGS, Clinical Affairs Core Committee (CACC), and Council. The version approved by the CGS and CACC was placed on The Endocrine Society’s Web site for comments by members. At each stage of review, the Task Force received written comments and incorporated needed changes.

Conclusions: We recommend case detection of primary aldosteronism be sought in higher risk groups of hypertensive patients and those with hypokalemia by determining the aldosterone-renin ratio under standard conditions and that the condition be confirmed/excluded by one of four commonly used confirmatory tests. We recommend that all patients with primary aldosteronism undergo adrenal computed tomography as the initial study in subtype testing and to exclude adrenocortical carcinoma. We recommend the presence of a unilateral form of primary aldosteronism should be established/excluded by bilateral adrenal venous sampling by an experienced radiologist and, where present, optimally treated by laparoscopic adrenalectomy. We recommend that patients with bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, or those unsuitable for surgery, optimally be treated medically by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

Summary of Recommendations

1.0 Case detection

1.1 We recommend the case detection of primary aldosteronism (PA) in patient groups with relatively high prevalence of PA. (1|⊕⊕OO) These include patients with Joint National Commission stage 2 (>160–179/100–109 mm Hg), stage 3 (>180/110 mm Hg), or drug-resistant hypertension; hypertension and spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia; hypertension with adrenal incidentaloma; or hypertension and a family history of early-onset hypertension or cerebrovascular accident at a young age (<40 yr). We also recommend case detection for all hypertensive first-degree relatives of patients with PA. (1|⊕OOO)

1.2 We recommend use of the plasma aldosterone to renin ratio (ARR) to detect cases of PA in these patient groups. (1|⊕⊕OO)

2.0 Case confirmation

2.1 Instead of proceeding directly to subtype classification, we recommend that patients with a positive ARR undergo testing, by any of four confirmatory tests, to definitively confirm or exclude the diagnosis. (1|⊕⊕OO)

3.0 Subtype classification

3.1 We recommend that all patients with PA undergo an adrenal computed tomography (CT) scan as the initial study in subtype testing and to exclude large masses that may represent adrenocortical carcinoma. (1|⊕⊕OO)

3.2 We recommend that, when surgical treatment is practicable and desired by the patient, the distinction between unilateral and bilateral adrenal disease be made by adrenal venous sampling (AVS) by an experienced radiologist. (1|⊕⊕⊕O)

3.3 In patients with onset of confirmed PA earlier than at 20 yr of age and in those who have a family history of PA or of strokes at young age (<40 yr), we suggest genetic testing for glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism (GRA). (2|⊕OOO)

4.0 Treatment

4.1 We recommend that treatment by unilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy be offered to patients with documented unilateral PA [i.e. aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) or unilateral adrenal hyperplasia (UAH)]. (1|⊕⊕OO) If a patient is unable or unwilling to undergo surgery, we recommend medical treatment with a mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonist. (1|⊕⊕OO)

4.2 In patients with PA due to bilateral adrenal disease, we recommend medical treatment with an MR antagonist (1|⊕⊕ OO); we suggest spironolactone as the primary agent with eplerenone as an alternative. (2|⊕OOO)

4.3 In patients with GRA, we recommend the use of the lowest dose of glucocorticoid that can normalize blood pressure and serum potassium levels rather than first-line treatment with an MR antagonist. (1|⊕OOO)

Method of Development of Evidence-Based Guidelines

The Clinical Guidelines Subcommittee of The Endocrine Society deemed detection, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with PA a priority area in need of practice guidelines and appointed a seven-member Task Force to formulate evidence-based recommendations. The Task Force followed the approach recommended by the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) group, an international group with expertise in development and implementation of evidence-based guidelines (1).

The Task Force used the best available research evidence that members identified to inform the recommendations and consistent language and graphical descriptions of both the strength of a recommendation and the quality of evidence. In terms of the strength of the recommendation, strong recommendations use the phrase “we recommend” and the number 1, and weak recommendations use the phrase “we suggest” and the number 2. Cross-filled circles indicate the quality of the evidence, such that ⊕OOO denotes very low quality evidence; ⊕⊕OO, low quality; ⊕⊕⊕O, moderate quality; and ⊕⊕⊕⊕, high quality. The Task Force has confidence that patients who receive care according to the strong recommendations will derive, on average, more good than harm. Weak recommendations require more careful consideration of the patient’s circumstances, values, and preferences to determine the best course of action. A detailed description of this grading scheme has been published elsewhere (2).

Linked to each recommendation is a description of the evidence, values that panelists considered in making the recommendation (when making these explicit was necessary), and remarks, a section in which panelists offer technical suggestions for testing conditions, dosing, and monitoring. These technical comments reflect the best available evidence applied to a typical patient. Often, this evidence comes from the unsystematic observations of the panelists and should, therefore, be considered suggestions.

Definition and Clinical Significance of PA

What is PA?

PA is a group of disorders in which aldosterone production is inappropriately high, relatively autonomous from the renin-angiotensin system, and nonsuppressible by sodium loading. Such inappropriate production of aldosterone causes cardiovascular damage, suppression of plasma renin, hypertension, sodium retention, and potassium excretion that if prolonged and severe may lead to hypokalemia. PA is commonly caused by an adrenal adenoma, by unilateral or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, or in rare cases by the inherited condition of GRA.

How common is PA?

Most experts previously described PA in less than 1% of patients with mild-to-moderate essential hypertension and had assumed hypokalemia was a sine qua non for diagnosis (3–9). Accumulating evidence has challenged these assumptions. Cross-sectional and prospective studies report PA in more than 10% of hypertensive patients, both in general and in specialty settings (10–18).

How frequent is hypokalemia in PA?

In recent studies, only a minority of patients with PA (9–37%) had hypokalemia (19). Thus, normokalemic hypertension constitutes the most common presentation of the disease, with hypokalemia probably present in only the more severe cases. Half the patients with an APA and 17% of those with idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA) had serum potassium concentrations less than 3.5 mmol/liter (17, 20). Thus, the presence of hypokalemia has low sensitivity and specificity and a low positive predictive value for the diagnosis of PA.

Why is PA important?

This condition is important not only because of its prevalence but also because PA patients have higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality than age- and sex-matched patients with essential hypertension and the same degree of blood pressure elevation (21, 22). Furthermore, specific treatments are available that ameliorate the impact of this condition on patient-important outcomes.

1.0 Case Detection

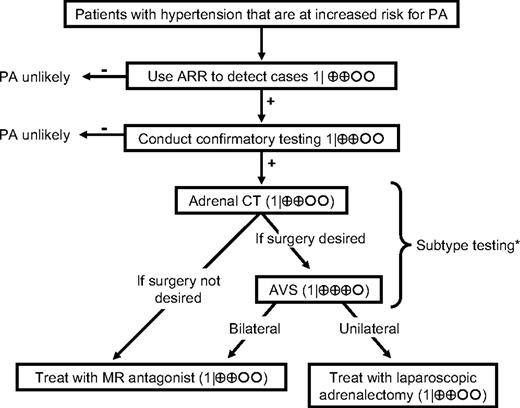

1.1 We recommend the case detection of PA in patient groups with relatively high prevalence of PA (listed in Table 1) (Fig. 1). (1|⊕⊕OO) These include patients with Joint National Commission stage 2 (>160–179/100–109 mm Hg), stage 3 (>180/110 mm Hg), or drug-resistant hypertension; hypertension and spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia; hypertension with adrenal incidentaloma; or hypertension and a family history of early-onset hypertension or cerebrovascular accident at a young age (<40 yr). We also recommend case detection for all hypertensive first-degree relatives of patients with PA. (1|⊕OOO)

| Patient group . | Prevalence . |

|---|---|

| Moderate/severe hypertension. The prevalence rates cited here are from Mosso et al. (16). Others have reported similar estimates (18, 23–25). The classification of blood pressure for adults (aged 18 yr and older) was based on the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, which establishes three different stages: stage 1, SBP 140–159, DBP 90–99; stage 2, SBP 160–179, DBP 100–109; stage 3, SBP > 180, DBP > 110 (10). When SBP and DBP were in different categories, the higher category was selected to classify the individual’s blood pressure status. | Overall, 6.1%; stage 1 (mild), 2%; stage 2 (moderate), 8%; stage 3 (severe), 13% |

| Resistant hypertension, defined as SBP > 140 and DBP > 90 despite treatment with three hypertensive medications. The prevalence rates cited here are from Refs. 26–31. | 17–23% |

| Hypertensive patients with spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia. | Specific prevalence figures are not available, but PA is more frequently found in this group. |

| Hypertension with adrenal incidentaloma (32–37), defined as an adrenal mass detected incidentally during imaging performed for extraadrenal reasons. | Median, 2% (range, 1.1–10%) One retrospective study that excluded patients with hypokalemia and severe hypertension found APA in 16 of 1004 subjects (37). |

| Patient group . | Prevalence . |

|---|---|

| Moderate/severe hypertension. The prevalence rates cited here are from Mosso et al. (16). Others have reported similar estimates (18, 23–25). The classification of blood pressure for adults (aged 18 yr and older) was based on the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, which establishes three different stages: stage 1, SBP 140–159, DBP 90–99; stage 2, SBP 160–179, DBP 100–109; stage 3, SBP > 180, DBP > 110 (10). When SBP and DBP were in different categories, the higher category was selected to classify the individual’s blood pressure status. | Overall, 6.1%; stage 1 (mild), 2%; stage 2 (moderate), 8%; stage 3 (severe), 13% |

| Resistant hypertension, defined as SBP > 140 and DBP > 90 despite treatment with three hypertensive medications. The prevalence rates cited here are from Refs. 26–31. | 17–23% |

| Hypertensive patients with spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia. | Specific prevalence figures are not available, but PA is more frequently found in this group. |

| Hypertension with adrenal incidentaloma (32–37), defined as an adrenal mass detected incidentally during imaging performed for extraadrenal reasons. | Median, 2% (range, 1.1–10%) One retrospective study that excluded patients with hypokalemia and severe hypertension found APA in 16 of 1004 subjects (37). |

DBP, Diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

| Patient group . | Prevalence . |

|---|---|

| Moderate/severe hypertension. The prevalence rates cited here are from Mosso et al. (16). Others have reported similar estimates (18, 23–25). The classification of blood pressure for adults (aged 18 yr and older) was based on the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, which establishes three different stages: stage 1, SBP 140–159, DBP 90–99; stage 2, SBP 160–179, DBP 100–109; stage 3, SBP > 180, DBP > 110 (10). When SBP and DBP were in different categories, the higher category was selected to classify the individual’s blood pressure status. | Overall, 6.1%; stage 1 (mild), 2%; stage 2 (moderate), 8%; stage 3 (severe), 13% |

| Resistant hypertension, defined as SBP > 140 and DBP > 90 despite treatment with three hypertensive medications. The prevalence rates cited here are from Refs. 26–31. | 17–23% |

| Hypertensive patients with spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia. | Specific prevalence figures are not available, but PA is more frequently found in this group. |

| Hypertension with adrenal incidentaloma (32–37), defined as an adrenal mass detected incidentally during imaging performed for extraadrenal reasons. | Median, 2% (range, 1.1–10%) One retrospective study that excluded patients with hypokalemia and severe hypertension found APA in 16 of 1004 subjects (37). |

| Patient group . | Prevalence . |

|---|---|

| Moderate/severe hypertension. The prevalence rates cited here are from Mosso et al. (16). Others have reported similar estimates (18, 23–25). The classification of blood pressure for adults (aged 18 yr and older) was based on the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, which establishes three different stages: stage 1, SBP 140–159, DBP 90–99; stage 2, SBP 160–179, DBP 100–109; stage 3, SBP > 180, DBP > 110 (10). When SBP and DBP were in different categories, the higher category was selected to classify the individual’s blood pressure status. | Overall, 6.1%; stage 1 (mild), 2%; stage 2 (moderate), 8%; stage 3 (severe), 13% |

| Resistant hypertension, defined as SBP > 140 and DBP > 90 despite treatment with three hypertensive medications. The prevalence rates cited here are from Refs. 26–31. | 17–23% |

| Hypertensive patients with spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia. | Specific prevalence figures are not available, but PA is more frequently found in this group. |

| Hypertension with adrenal incidentaloma (32–37), defined as an adrenal mass detected incidentally during imaging performed for extraadrenal reasons. | Median, 2% (range, 1.1–10%) One retrospective study that excluded patients with hypokalemia and severe hypertension found APA in 16 of 1004 subjects (37). |

DBP, Diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Algorithm for the detection, confirmation, subtype testing, and treatment of PA. We recommend the case detection of PA in patient groups with relatively high prevalence of PA (1|⊕⊕OO); these include patients with moderate, severe, or resistant hypertension, spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalemia, hypertension with adrenal incidentaloma, or a family history of early-onset hypertension or cerebrovascular accident at a young age (<40 yr). We recommend use of the plasma ARR to detect cases of PA in these patient groups (1|⊕⊕OO). We recommend that patients with a positive ARR undergo testing, using any of four confirmatory tests, to definitively confirm or exclude the diagnosis (1|⊕⊕OO). We recommend that all patients with PA undergo an adrenal CT scan as the initial study in subtype testing and to exclude adrenocortical carcinoma (1|⊕⊕OO). When surgical treatment is practicable and desired by the patient, the distinction between unilateral and bilateral adrenal disease should be made by AVS (1|⊕⊕⊕O). We recommend that treatment by unilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy be offered to patients with AVS-documented unilateral APA (1|⊕⊕OO). If a patient is unable or unwilling to undergo surgery, we recommend medical treatment with an MR antagonist (1|⊕⊕OO). In patients with PA due to bilateral adrenal disease, we recommend medical treatment with an MR antagonist (1|⊕OOO). *, In patients with confirmed PA who have a family history of PA or of strokes at young age (<40 yr), or with onset of hypertension earlier than at 20 yr of age, we suggest genetic testing for GRA (2|⊕OOO). In patients with GRA, we recommend the use of the lowest dose of glucocorticoid receptor agonist that can normalize blood pressure and serum potassium levels (1|⊕OOO).

1.1 Evidence

Indirect evidence links the detection of PA with improved patient outcomes. There are no clinical trials of screening that measure the impact of this practice on morbidity, mortality, or quality-of-life outcomes. Patients could potentially be harmed by the work-up and treatment (i.e. by withdrawal of antihypertensive medication, invasive vascular examination, or adrenalectomy) aimed at vascular protection along with easier and better blood pressure control. There is strong evidence linking improved blood pressure control and reduction in aldosterone levels to improved cardiac and cerebrovascular outcomes (38). Until prospective studies inform us differently, we recommend that all hypertensive first-degree relatives of patients with PA undergo ARR testing.

1.1 Values

Our recommendation to detect cases of PA places a high value on avoiding the risks associated with missing the diagnosis (and thus forgoing the opportunity of a surgical cure or improved control of hypertension through specific medical treatment) and a lower value on avoiding the risk of falsely classifying a hypertensive patient as having PA and exposing him or her to additional diagnostic testing.

1.2 We recommend use of the plasma ARR to detect cases of PA in these patient groups (Fig. 1). (1|⊕⊕OO)

1.2 Evidence

The ARR is currently the most reliable available means of screening for PA. Although valid estimates of test characteristics of the ARR are lacking (mainly due to limitations in the design of studies that have addressed this issue) (39), numerous studies have demonstrated the ARR to be superior to measurement of potassium or aldosterone (both of which have lower sensitivity) or of renin (which is less specific) in isolation (40–42).

Like all biochemical case detection tests, the ARR is not without false positives and negatives (17, 18, 39, 43–45). Table 2 documents the effect of medications and conditions on the ARR. The ARR should therefore be regarded as a detection test only and should be repeated if the initial results are inconclusive or difficult to interpret because of suboptimal sampling conditions (e.g. maintenance of some medications listed in Table 2).

Medications that have minimal effects on plasma aldosterone levels and can be used to control hypertension during case finding and confirmatory testing for PA

| Drug . | Class . | Usual dose . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verapamil slow-release | Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist | 90–120 mg twice daily | Use singly or in combination with the other agents listed in this table. |

| Hydralazine | Vasodilator | 10–12.5 mg twice daily, increasing as required | Commence verapamil slow release first to prevent reflex tachycardia. Commencement at low doses reduces risk of side effects (including headaches, flushing, and palpitations). |

| Prazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 0.5–1 mg two to three times daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Doxazosin mesylate | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Terazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Drug . | Class . | Usual dose . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verapamil slow-release | Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist | 90–120 mg twice daily | Use singly or in combination with the other agents listed in this table. |

| Hydralazine | Vasodilator | 10–12.5 mg twice daily, increasing as required | Commence verapamil slow release first to prevent reflex tachycardia. Commencement at low doses reduces risk of side effects (including headaches, flushing, and palpitations). |

| Prazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 0.5–1 mg two to three times daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Doxazosin mesylate | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Terazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

Medications that have minimal effects on plasma aldosterone levels and can be used to control hypertension during case finding and confirmatory testing for PA

| Drug . | Class . | Usual dose . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verapamil slow-release | Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist | 90–120 mg twice daily | Use singly or in combination with the other agents listed in this table. |

| Hydralazine | Vasodilator | 10–12.5 mg twice daily, increasing as required | Commence verapamil slow release first to prevent reflex tachycardia. Commencement at low doses reduces risk of side effects (including headaches, flushing, and palpitations). |

| Prazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 0.5–1 mg two to three times daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Doxazosin mesylate | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Terazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Drug . | Class . | Usual dose . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verapamil slow-release | Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist | 90–120 mg twice daily | Use singly or in combination with the other agents listed in this table. |

| Hydralazine | Vasodilator | 10–12.5 mg twice daily, increasing as required | Commence verapamil slow release first to prevent reflex tachycardia. Commencement at low doses reduces risk of side effects (including headaches, flushing, and palpitations). |

| Prazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 0.5–1 mg two to three times daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Doxazosin mesylate | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

| Terazosin hydrochloride | α-Adrenergic blocker | 1–2 mg once daily, increasing as required | Monitor for postural hypotension |

1.2 Values

Similar values underpin our recommendation to target subjects in groups with documented high prevalence of PA and to test them by ARR. In particular, this recommendation acknowledges the costs currently associated with ARR testing of all patients with essential hypertension. Against this recommendation for selective testing, however, must be weighed the risk of missing or at least delaying the diagnosis of PA in some hypertensive individuals. The consequences of this may include the later development of more severe and resistant hypertension resulting from failure to lower levels of aldosterone or to block its actions. Furthermore, duration of hypertension has been reported by several investigators to be a negative predictor of outcome after unilateral adrenalectomy for APA (46, 47), suggesting that delays in diagnosis may result in a poorer response to specific treatment once PA is finally diagnosed.

1.2 Remarks: technical aspects required for the correct implementation of recommendation 1.2

Testing conditions (Tables 3 and 4)

| ARR measurement . |

|---|

| A. Preparation for ARR measurement: agenda |

| 1. Attempt to correct hypokalemia, after measuring plasma potassium in blood collected slowly with a syringe and needle (preferably not a Vacutainer to minimize the risk of spuriously raising potassium); avoid fist clenching during collection; wait at least 5 sec after tourniquet release (if used to achieve insertion of needle) and ensure separation of plasma from cells within 30 min of collection. |

| 2. Encourage patient to liberalize (rather than restrict) sodium intake. |

| 3. Withdraw agents that markedly affect the ARR (48) for at least 4 wk: |

| a. Spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, and triamterene |

| b. Potassium-wasting diuretics |

| c. Products derived from licorice root (e.g. confectionary licorice, chewing tobacco) |

| 4. If the results of ARR off the above agents are not diagnostic, and if hypertension can be controlled with relatively noninterfering medications (see Table 2), withdraw other medications that may affect the ARR (48) for at least 2 wk: |

| a. β-Adrenergic blockers, central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs |

| b. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, renin inhibitors, dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists |

| 5. If necessary to maintain hypertension control, commence other antihypertensive medications that have lesser effects on the ARR [e.g. verapamil slow-release, hydralazine (with verapamil slow-release, to avoid reflex tachycardia), prazosin, doxazosin, terazosin; see Table 2]. |

| 6. Establish OC and HRT status, because estrogen-containing medications may lower DRC and cause false-positive ARR when DRC (rather than PRA) is measured. Do not withdraw OC unless confident of alternative effective contraception. |

| B. Conditions for collection of blood |

| 1. Collect blood mid-morning, after the patient has been up (sitting, standing, or walking) for at least 2 h and seated for 5–15 min. |

| 2. Collect blood carefully, avoiding stasis and hemolysis (see A.1 above). |

| 3. Maintain sample at room temperature (and not on ice, because this will promote conversion of inactive to active renin) during delivery to laboratory and before centrifugation and rapid freezing of plasma component pending assay. |

| C. Factors to take into account when interpreting results (see Table 4) |

| 1. Age: in patients aged >65 yr, renin can be lowered more than aldosterone by age alone, leading to a raised ARR |

| 2. Time of day, recent diet, posture, and length of time in that posture |

| 3. Medications |

| 4. Method of blood collection, including any difficulty doing so |

| 5. Level of potassium |

| 6. Level of creatinine (renal failure can lead to false-positive ARR) |

| ARR measurement . |

|---|

| A. Preparation for ARR measurement: agenda |

| 1. Attempt to correct hypokalemia, after measuring plasma potassium in blood collected slowly with a syringe and needle (preferably not a Vacutainer to minimize the risk of spuriously raising potassium); avoid fist clenching during collection; wait at least 5 sec after tourniquet release (if used to achieve insertion of needle) and ensure separation of plasma from cells within 30 min of collection. |

| 2. Encourage patient to liberalize (rather than restrict) sodium intake. |

| 3. Withdraw agents that markedly affect the ARR (48) for at least 4 wk: |

| a. Spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, and triamterene |

| b. Potassium-wasting diuretics |

| c. Products derived from licorice root (e.g. confectionary licorice, chewing tobacco) |

| 4. If the results of ARR off the above agents are not diagnostic, and if hypertension can be controlled with relatively noninterfering medications (see Table 2), withdraw other medications that may affect the ARR (48) for at least 2 wk: |

| a. β-Adrenergic blockers, central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs |

| b. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, renin inhibitors, dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists |

| 5. If necessary to maintain hypertension control, commence other antihypertensive medications that have lesser effects on the ARR [e.g. verapamil slow-release, hydralazine (with verapamil slow-release, to avoid reflex tachycardia), prazosin, doxazosin, terazosin; see Table 2]. |

| 6. Establish OC and HRT status, because estrogen-containing medications may lower DRC and cause false-positive ARR when DRC (rather than PRA) is measured. Do not withdraw OC unless confident of alternative effective contraception. |

| B. Conditions for collection of blood |

| 1. Collect blood mid-morning, after the patient has been up (sitting, standing, or walking) for at least 2 h and seated for 5–15 min. |

| 2. Collect blood carefully, avoiding stasis and hemolysis (see A.1 above). |

| 3. Maintain sample at room temperature (and not on ice, because this will promote conversion of inactive to active renin) during delivery to laboratory and before centrifugation and rapid freezing of plasma component pending assay. |

| C. Factors to take into account when interpreting results (see Table 4) |

| 1. Age: in patients aged >65 yr, renin can be lowered more than aldosterone by age alone, leading to a raised ARR |

| 2. Time of day, recent diet, posture, and length of time in that posture |

| 3. Medications |

| 4. Method of blood collection, including any difficulty doing so |

| 5. Level of potassium |

| 6. Level of creatinine (renal failure can lead to false-positive ARR) |

HRT, Hormone replacement therapy; OC, oral contraceptive.

| ARR measurement . |

|---|

| A. Preparation for ARR measurement: agenda |

| 1. Attempt to correct hypokalemia, after measuring plasma potassium in blood collected slowly with a syringe and needle (preferably not a Vacutainer to minimize the risk of spuriously raising potassium); avoid fist clenching during collection; wait at least 5 sec after tourniquet release (if used to achieve insertion of needle) and ensure separation of plasma from cells within 30 min of collection. |

| 2. Encourage patient to liberalize (rather than restrict) sodium intake. |

| 3. Withdraw agents that markedly affect the ARR (48) for at least 4 wk: |

| a. Spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, and triamterene |

| b. Potassium-wasting diuretics |

| c. Products derived from licorice root (e.g. confectionary licorice, chewing tobacco) |

| 4. If the results of ARR off the above agents are not diagnostic, and if hypertension can be controlled with relatively noninterfering medications (see Table 2), withdraw other medications that may affect the ARR (48) for at least 2 wk: |

| a. β-Adrenergic blockers, central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs |

| b. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, renin inhibitors, dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists |

| 5. If necessary to maintain hypertension control, commence other antihypertensive medications that have lesser effects on the ARR [e.g. verapamil slow-release, hydralazine (with verapamil slow-release, to avoid reflex tachycardia), prazosin, doxazosin, terazosin; see Table 2]. |

| 6. Establish OC and HRT status, because estrogen-containing medications may lower DRC and cause false-positive ARR when DRC (rather than PRA) is measured. Do not withdraw OC unless confident of alternative effective contraception. |

| B. Conditions for collection of blood |

| 1. Collect blood mid-morning, after the patient has been up (sitting, standing, or walking) for at least 2 h and seated for 5–15 min. |

| 2. Collect blood carefully, avoiding stasis and hemolysis (see A.1 above). |

| 3. Maintain sample at room temperature (and not on ice, because this will promote conversion of inactive to active renin) during delivery to laboratory and before centrifugation and rapid freezing of plasma component pending assay. |

| C. Factors to take into account when interpreting results (see Table 4) |

| 1. Age: in patients aged >65 yr, renin can be lowered more than aldosterone by age alone, leading to a raised ARR |

| 2. Time of day, recent diet, posture, and length of time in that posture |

| 3. Medications |

| 4. Method of blood collection, including any difficulty doing so |

| 5. Level of potassium |

| 6. Level of creatinine (renal failure can lead to false-positive ARR) |

| ARR measurement . |

|---|

| A. Preparation for ARR measurement: agenda |

| 1. Attempt to correct hypokalemia, after measuring plasma potassium in blood collected slowly with a syringe and needle (preferably not a Vacutainer to minimize the risk of spuriously raising potassium); avoid fist clenching during collection; wait at least 5 sec after tourniquet release (if used to achieve insertion of needle) and ensure separation of plasma from cells within 30 min of collection. |

| 2. Encourage patient to liberalize (rather than restrict) sodium intake. |

| 3. Withdraw agents that markedly affect the ARR (48) for at least 4 wk: |

| a. Spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, and triamterene |

| b. Potassium-wasting diuretics |

| c. Products derived from licorice root (e.g. confectionary licorice, chewing tobacco) |

| 4. If the results of ARR off the above agents are not diagnostic, and if hypertension can be controlled with relatively noninterfering medications (see Table 2), withdraw other medications that may affect the ARR (48) for at least 2 wk: |

| a. β-Adrenergic blockers, central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs |

| b. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, renin inhibitors, dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists |

| 5. If necessary to maintain hypertension control, commence other antihypertensive medications that have lesser effects on the ARR [e.g. verapamil slow-release, hydralazine (with verapamil slow-release, to avoid reflex tachycardia), prazosin, doxazosin, terazosin; see Table 2]. |

| 6. Establish OC and HRT status, because estrogen-containing medications may lower DRC and cause false-positive ARR when DRC (rather than PRA) is measured. Do not withdraw OC unless confident of alternative effective contraception. |

| B. Conditions for collection of blood |

| 1. Collect blood mid-morning, after the patient has been up (sitting, standing, or walking) for at least 2 h and seated for 5–15 min. |

| 2. Collect blood carefully, avoiding stasis and hemolysis (see A.1 above). |

| 3. Maintain sample at room temperature (and not on ice, because this will promote conversion of inactive to active renin) during delivery to laboratory and before centrifugation and rapid freezing of plasma component pending assay. |

| C. Factors to take into account when interpreting results (see Table 4) |

| 1. Age: in patients aged >65 yr, renin can be lowered more than aldosterone by age alone, leading to a raised ARR |

| 2. Time of day, recent diet, posture, and length of time in that posture |

| 3. Medications |

| 4. Method of blood collection, including any difficulty doing so |

| 5. Level of potassium |

| 6. Level of creatinine (renal failure can lead to false-positive ARR) |

HRT, Hormone replacement therapy; OC, oral contraceptive.

Factors that may affect the ARR and thus lead to false-positive or false-negative results

| Factor . | Effect on aldosterone levels . | Effect on renin levels . | Effect on ARR . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medications | |||

| β-Adrenergic blockers | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa) | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| NSAIDs | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| K+-wasting diuretics | →↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| K+-sparing diuretics | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ACE inhibitors | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ARBs | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Ca2+ blockers (DHPs) | →↓ | ↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renin inhibitors | ↓ | ↓↑a | ↑ (FP)a |

| ↓ (FN)a | |||

| Potassium status | |||

| Hypokalemia | ↓ | →↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Potassium loading | ↑ | →↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Dietary sodium | |||

| Sodium restricted | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Sodium loaded | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Advancing age | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Other conditions | |||

| Renal impairment | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| PHA-2 | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Pregnancy | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renovascular HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Malignant HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Factor . | Effect on aldosterone levels . | Effect on renin levels . | Effect on ARR . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medications | |||

| β-Adrenergic blockers | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa) | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| NSAIDs | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| K+-wasting diuretics | →↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| K+-sparing diuretics | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ACE inhibitors | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ARBs | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Ca2+ blockers (DHPs) | →↓ | ↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renin inhibitors | ↓ | ↓↑a | ↑ (FP)a |

| ↓ (FN)a | |||

| Potassium status | |||

| Hypokalemia | ↓ | →↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Potassium loading | ↑ | →↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Dietary sodium | |||

| Sodium restricted | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Sodium loaded | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Advancing age | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Other conditions | |||

| Renal impairment | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| PHA-2 | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Pregnancy | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renovascular HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Malignant HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker; DHP, dihydropyridine; FP, false positive; FN, false negative; HT, hypertension; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; PHA-2, pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2 (familial hypertension and hyperkalemia with normal glomerular filtration rate).

Renin inhibitors lower PRA but raise DRC. This would be expected to result in false-positive ARR levels for renin measured as PRA and false negatives for renin measured as DRC.

Factors that may affect the ARR and thus lead to false-positive or false-negative results

| Factor . | Effect on aldosterone levels . | Effect on renin levels . | Effect on ARR . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medications | |||

| β-Adrenergic blockers | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa) | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| NSAIDs | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| K+-wasting diuretics | →↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| K+-sparing diuretics | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ACE inhibitors | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ARBs | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Ca2+ blockers (DHPs) | →↓ | ↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renin inhibitors | ↓ | ↓↑a | ↑ (FP)a |

| ↓ (FN)a | |||

| Potassium status | |||

| Hypokalemia | ↓ | →↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Potassium loading | ↑ | →↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Dietary sodium | |||

| Sodium restricted | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Sodium loaded | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Advancing age | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Other conditions | |||

| Renal impairment | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| PHA-2 | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Pregnancy | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renovascular HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Malignant HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Factor . | Effect on aldosterone levels . | Effect on renin levels . | Effect on ARR . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medications | |||

| β-Adrenergic blockers | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Central α-2 agonists (e.g. clonidine and α-methyldopa) | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| NSAIDs | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| K+-wasting diuretics | →↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| K+-sparing diuretics | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ACE inhibitors | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| ARBs | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Ca2+ blockers (DHPs) | →↓ | ↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renin inhibitors | ↓ | ↓↑a | ↑ (FP)a |

| ↓ (FN)a | |||

| Potassium status | |||

| Hypokalemia | ↓ | →↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Potassium loading | ↑ | →↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Dietary sodium | |||

| Sodium restricted | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Sodium loaded | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Advancing age | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Other conditions | |||

| Renal impairment | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| PHA-2 | → | ↓ | ↑ (FP) |

| Pregnancy | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Renovascular HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

| Malignant HT | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ (FN) |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker; DHP, dihydropyridine; FP, false positive; FN, false negative; HT, hypertension; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; PHA-2, pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2 (familial hypertension and hyperkalemia with normal glomerular filtration rate).

Renin inhibitors lower PRA but raise DRC. This would be expected to result in false-positive ARR levels for renin measured as PRA and false negatives for renin measured as DRC.

The ARR is most sensitive when used in patients from whom samples are collected in the morning after patients have been out of bed for at least 2 h, usually after they have been seated for 5–15 min. Ideally, patients should have unrestricted dietary salt intake before testing. In many cases, the ARR can be confidently interpreted with knowledge of the effect on the ARR of continued medications or suboptimal conditions of testing, avoiding delay and allowing the patient to proceed directly to confirmatory/exclusion testing. Washout of all interfering antihypertensive medications is feasible in patients with mild hypertension but is potentially problematic in others, and perhaps unnecessary in that medications with minimal effect on the ARR can be used in their place (Table 2).

Assay reliability

Although newer techniques are evolving, we prefer to use validated immunometric assays for plasma renin activity (PRA) or direct renin concentration (DRC); PRA takes into account factors (such as estrogen-containing preparations) that affect endogenous substrate levels. Laboratories should use aliquots from human plasma pools, carefully selected to cover the critical range of measurements, rather than the lyophilized controls provided by the manufacturer to monitor intra- and interassay reproducibility and long-term stability. Because the ARR is mathematically highly dependent on renin (49), renin assays should be sufficiently sensitive to measure levels as low as 0.2–0.3 ng/ml·h (DRC 2 mU/liter) (10, 16). For PRA, but not DRC, sensitivity for levels less than 1 ng/ml·h can be improved by prolonging the duration of the assay incubation phase as suggested by Sealey and Laragh (50). Although most laboratories use RIA for plasma and urinary aldosterone, measured levels of standards have been shown to be unacceptably different in some instances (51). Tandem mass spectrometry is increasingly used and has proved to be much more consistent in performance (52).

Interpretation

There are important and confusing differences between laboratories in the methods and units used to report values of renin and aldosterone. For aldosterone, 1 ng/dl converts to 27.7 pmol/liter in Système International (SI) units. For immunometric methods of directly measuring renin concentration, a PRA level of 1 ng/ml·h (12.8 pmol/liter·min in SI units) converts to a DRC of approximately 8.2 mU/liter (5.2 ng/liter in traditional units) when measured by either the Nichols Institute Diagnostics automated chemiluminescence immunoassay (previously widely used but recently withdrawn) or the Bio-Rad Renin II RIA. Because DRC assays are still in evolution, these conversion factors may change. For example, 1 ng/ml·h PRA converts to a DRC of approximately 12 mU/liter (7.6 ng/liter) when measured by the recently introduced and already widely used Diasorin automated chemiluminescence immunoassay. Here, we express aldosterone and PRA levels in conventional units (aldosterone in nanograms per deciliter; PRA in nanograms per milliliter per hour) with SI units for aldosterone and DRC (using the 8.2 conversion factor) given in parentheses. Lack of uniformity in diagnostic protocols and assay methods for ARR measurement has been associated with substantial variability in cutoff values used by different groups ranging from 20–100 (68–338) (11, 14, 15, 19, 29, 53, 54). Most groups, however, use cutoffs of 20–40 (68–135) when testing is performed in the morning on a seated ambulatory patient. Table 5 lists ARR cutoff values using some commonly expressed assay units for plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC), PRA, and direct measurement of plasma renin concentration.

ARR cutoff values, depending on assay and based on whether PAC, PRA, and DRC are measured in conventional or SI units

| . | PRA (ng/ml·h) . | PRA (pmol/liter·min) . | DRCa (mU/liter) . | DRCa (ng/liter) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAC (ng/dl) | 20 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 3.8 |

| 30b | 2.5 | 3.7 | 5.7 | |

| 40 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 7.7 | |

| PAC (pmol/liter) | 750b | 60 | 91 | 144 |

| 1000 | 80 | 122 | 192 |

| . | PRA (ng/ml·h) . | PRA (pmol/liter·min) . | DRCa (mU/liter) . | DRCa (ng/liter) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAC (ng/dl) | 20 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 3.8 |

| 30b | 2.5 | 3.7 | 5.7 | |

| 40 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 7.7 | |

| PAC (pmol/liter) | 750b | 60 | 91 | 144 |

| 1000 | 80 | 122 | 192 |

Values shown are on the basis of a conversion factor of PRA (ng/ml·h) to DRC (mU/liter) of 8.2. DRC assays are still in evolution, and in a recently introduced and already commonly used automated DRC assay, the conversion factor is 12 (see text).

The most commonly adopted cutoff values are shown in bold: 30 for PAC and PRA in conventional units (equivalent to 830 when PAC is in SI units) and 750 when PAC is expressed in SI units (equivalent to 27 in conventional units).

ARR cutoff values, depending on assay and based on whether PAC, PRA, and DRC are measured in conventional or SI units

| . | PRA (ng/ml·h) . | PRA (pmol/liter·min) . | DRCa (mU/liter) . | DRCa (ng/liter) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAC (ng/dl) | 20 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 3.8 |

| 30b | 2.5 | 3.7 | 5.7 | |

| 40 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 7.7 | |

| PAC (pmol/liter) | 750b | 60 | 91 | 144 |

| 1000 | 80 | 122 | 192 |

| . | PRA (ng/ml·h) . | PRA (pmol/liter·min) . | DRCa (mU/liter) . | DRCa (ng/liter) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAC (ng/dl) | 20 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 3.8 |

| 30b | 2.5 | 3.7 | 5.7 | |

| 40 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 7.7 | |

| PAC (pmol/liter) | 750b | 60 | 91 | 144 |

| 1000 | 80 | 122 | 192 |

Values shown are on the basis of a conversion factor of PRA (ng/ml·h) to DRC (mU/liter) of 8.2. DRC assays are still in evolution, and in a recently introduced and already commonly used automated DRC assay, the conversion factor is 12 (see text).

The most commonly adopted cutoff values are shown in bold: 30 for PAC and PRA in conventional units (equivalent to 830 when PAC is in SI units) and 750 when PAC is expressed in SI units (equivalent to 27 in conventional units).

Some investigators require elevated aldosterone levels in addition to elevated ARR for a positive screening test for PA [usually aldosterone >15 ng/dl (416 pmol/liter)] (55). An alternative approach is to avoid a formal cutoff level for plasma aldosterone but to recognize that the likelihood of a false-positive ARR becomes greater when renin levels are very low (11). Against a formal cutoff level for aldosterone are the findings of several studies. In one study, seated plasma aldosterone levels were less than 15 ng/dl (<416 pmol/liter) in 36% of 74 patients diagnosed with PA after screening positive by ARR defined as more than 30 (>100) and showing failure of aldosterone to suppress during fludrocortisone suppression testing (FST), and in four of 21 patients found by AVS to have unilateral, surgically correctable PA (56). Another study reported plasma aldosterone levels of 9–16 ng/dl (250–440 pmol/liter) in 16 of 37 patients diagnosed with PA by FST (16). Although it would clearly be desirable to provide firm recommendations for ARR and plasma aldosterone cutoffs, the variability of assays between laboratories and the divided literature to date make it more prudent to point out relative advantages and disadvantages, leaving clinicians the flexibility to judge for themselves.

2.0 Case Confirmation

2.1 Instead of proceeding directly to subtype classification, we recommend that patients with a positive aldosterone-renin ratio (ARR) measurement undergo testing, by any of four confirmatory tests, to definitively confirm or exclude the diagnosis (Fig. 1). (1|⊕⊕OO)

2.1 Evidence

The current literature does not identify a gold standard confirmatory test for PA. Test performance has been evaluated only retrospectively, in relatively small series of patients selected with high prior (pretest) probability of PA, commonly in comparison with other tests rather than toward a conclusive diagnosis of PA.

Some of these limitations are illustrated in the following example. There is empirical evidence that case-control designs for establishing the accuracy of diagnostic tests overestimate their accuracy. Giacchetti et al. (57) used such a design including 61 PA patients (26 with confirmed APA) and 157 patients with essential hypertension. In this context, they found that a post-sodium infusion test (SIT) with a cutoff value for plasma aldosterone of at least 7 ng/dl showed a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 100% when evaluated by receiver-operating characteristic curve in the 76 cases with ARR more than 40 ng/dl per ng/ml·h. In the prospective PAPY study, analysis of sensitivity/specificity in the 317 patients undergoing a SIT gave a best aldosterone cutoff value of 6.8 ng/dl. The sensitivity and specificity, however, were moderate (respectively, 83 and 75%), reflecting values overlapping between patients with and without disease; use of the aldosterone-cortisol ratio did not improve the accuracy of the test (17, 58).

Four testing procedures (oral sodium loading, saline infusion, fludrocortisone suppression, and captopril challenge) are in common use, and there is currently insufficient direct evidence to recommend one over the others. Although it is acknowledged that these tests may differ in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and reliability, the choice of confirmatory test is commonly determined by considerations of cost, patient compliance, laboratory routine, and local expertise (Table 6). It should be noted that confirmatory tests requiring oral or iv sodium loading should be administered with caution in patients with uncontrolled hypertension or congestive heart failure. We recommend that the pharmacological agents with minimal or no effects on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system shown in Table 2 be used to control blood pressure during confirmatory testing.

| Confirmatory test . | Procedure . | Interpretation . | Concerns . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral sodium loading test | Patients should increase their sodium intake to >200 mmol/d (∼6 g/d) for 3 d, verified by 24-h urine sodium content. Patients should receive adequate slow-release potassium chloride supplementation to maintain plasma potassium in the normal range. Urinary aldosterone is measured in the 24-h urine collection from the morning of d 3 to the morning of d 4. | PA is unlikely if urinary aldosterone is lower than 10 μg/24 h (27.7 nmol/d) in the absence of renal disease where PA may coexist with lower measured urinary aldosterone levels. Elevated urinary aldosterone excretion [>12 μg/24 h (>33.3 nmol/d) at the Mayo Clinic, >14 μg/24 h (38.8 nmol/d) at the Cleveland Clinic] makes PA highly likely. | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. The 24-h urine collection may be inconvenient. Laboratory-specific poor performance of the RIA for urinary aldosterone (aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide or acid-labile metabolite) may blunt diagnostic accuracy, a problem obviated by the currently available HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry methodology (52). Aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide is a renal metabolite, and its excretion may not rise in patients with renal disease. |

| SIT | Patients stay in the recumbent position for at least 1 h before and during the infusion of 2 liters of 0.9% saline iv over 4 h, starting at 0800–0930 h. Blood samples for renin, aldosterone, cortisol, and plasma potassium are drawn at time zero and after 4 h, with blood pressure and heart rate monitored throughout the test. | Postinfusion plasma aldosterone levels <5 ng/dl make the diagnosis of PA unlikely, and levels >10 ng/dl are a very probable sign of PA. Values between 5 and 10 ng/dl are indeterminate (57–60). | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. |

| FST | Patients receive 0.1 mg oral fludrocortisone every 6 h for 4 d, together with slow-release KCl supplements (every 6 h at doses sufficient to keep plasma K+, measured four times a day, close to 4.0 mmol/liter), slow-release NaCl supplements (30 mmol three times daily with meals) and sufficient dietary salt to maintain a urinary sodium excretion rate of at least 3 mmol/kg body weight. On d 4, plasma aldosterone and PRA are measured at 1000 h with the patient in the seated posture, and plasma cortisol is measured at 0700 and 1000 h. | Upright plasma aldosterone >6 ng/dl on d 4 at 1000 h confirms PA, provided PRA is < 1 ng/ml·h and plasma cortisol concentration is lower than the value obtained at 0700 h (to exclude a confounding ACTH effect) (42, 43, 56, 61–63). | Although some centers (10, 16) conduct this test in the outpatient setting (provided that patients are able to attend frequently to monitor their potassium), in other centers, several days of hospitalization are customary. |

| Most of the data available come from the Brisbane group (42, 43, 56, 61–63) who have established, on the basis of a very large series of patients, a cutoff of a plasma aldosterone concentration of 6 ng/dl at 1000 h in an ambulatory patient on d 4. | |||

| Proponents of the FST argue that 1) it is the most sensitive for confirming PA, 2) it is a less intrusive method of sodium loading than SIT and therefore less likely to provoke non-renin-dependent alterations of aldosterone levels, 3) it allows for the potentially confounding effects of potassium to be controlled and for ACTH (via cortisol) to be monitored and detected, and 4) it is safe when performed by experienced hands. | |||

| Captopril challenge test | Patients receive 25–50 mg captopril orally after sitting or standing for at least 1 h. Blood samples are drawn for measurement of PRA, plasma aldosterone, and cortisol at time zero and at 1 or 2 h after challenge, with the patient remaining seated during this period. | Plasma aldosterone is normally suppressed by captopril (>30%). In patients with PA, it remains elevated and PRA remains suppressed. Differences may be seen between patients with APA and those with IHA, in that some decrease of aldosterone levels is occasionally seen in IHA (23, 64–66). | There are reports of a substantial number of false-negative or equivocal results (67, 68). |

| Confirmatory test . | Procedure . | Interpretation . | Concerns . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral sodium loading test | Patients should increase their sodium intake to >200 mmol/d (∼6 g/d) for 3 d, verified by 24-h urine sodium content. Patients should receive adequate slow-release potassium chloride supplementation to maintain plasma potassium in the normal range. Urinary aldosterone is measured in the 24-h urine collection from the morning of d 3 to the morning of d 4. | PA is unlikely if urinary aldosterone is lower than 10 μg/24 h (27.7 nmol/d) in the absence of renal disease where PA may coexist with lower measured urinary aldosterone levels. Elevated urinary aldosterone excretion [>12 μg/24 h (>33.3 nmol/d) at the Mayo Clinic, >14 μg/24 h (38.8 nmol/d) at the Cleveland Clinic] makes PA highly likely. | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. The 24-h urine collection may be inconvenient. Laboratory-specific poor performance of the RIA for urinary aldosterone (aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide or acid-labile metabolite) may blunt diagnostic accuracy, a problem obviated by the currently available HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry methodology (52). Aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide is a renal metabolite, and its excretion may not rise in patients with renal disease. |

| SIT | Patients stay in the recumbent position for at least 1 h before and during the infusion of 2 liters of 0.9% saline iv over 4 h, starting at 0800–0930 h. Blood samples for renin, aldosterone, cortisol, and plasma potassium are drawn at time zero and after 4 h, with blood pressure and heart rate monitored throughout the test. | Postinfusion plasma aldosterone levels <5 ng/dl make the diagnosis of PA unlikely, and levels >10 ng/dl are a very probable sign of PA. Values between 5 and 10 ng/dl are indeterminate (57–60). | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. |

| FST | Patients receive 0.1 mg oral fludrocortisone every 6 h for 4 d, together with slow-release KCl supplements (every 6 h at doses sufficient to keep plasma K+, measured four times a day, close to 4.0 mmol/liter), slow-release NaCl supplements (30 mmol three times daily with meals) and sufficient dietary salt to maintain a urinary sodium excretion rate of at least 3 mmol/kg body weight. On d 4, plasma aldosterone and PRA are measured at 1000 h with the patient in the seated posture, and plasma cortisol is measured at 0700 and 1000 h. | Upright plasma aldosterone >6 ng/dl on d 4 at 1000 h confirms PA, provided PRA is < 1 ng/ml·h and plasma cortisol concentration is lower than the value obtained at 0700 h (to exclude a confounding ACTH effect) (42, 43, 56, 61–63). | Although some centers (10, 16) conduct this test in the outpatient setting (provided that patients are able to attend frequently to monitor their potassium), in other centers, several days of hospitalization are customary. |

| Most of the data available come from the Brisbane group (42, 43, 56, 61–63) who have established, on the basis of a very large series of patients, a cutoff of a plasma aldosterone concentration of 6 ng/dl at 1000 h in an ambulatory patient on d 4. | |||

| Proponents of the FST argue that 1) it is the most sensitive for confirming PA, 2) it is a less intrusive method of sodium loading than SIT and therefore less likely to provoke non-renin-dependent alterations of aldosterone levels, 3) it allows for the potentially confounding effects of potassium to be controlled and for ACTH (via cortisol) to be monitored and detected, and 4) it is safe when performed by experienced hands. | |||

| Captopril challenge test | Patients receive 25–50 mg captopril orally after sitting or standing for at least 1 h. Blood samples are drawn for measurement of PRA, plasma aldosterone, and cortisol at time zero and at 1 or 2 h after challenge, with the patient remaining seated during this period. | Plasma aldosterone is normally suppressed by captopril (>30%). In patients with PA, it remains elevated and PRA remains suppressed. Differences may be seen between patients with APA and those with IHA, in that some decrease of aldosterone levels is occasionally seen in IHA (23, 64–66). | There are reports of a substantial number of false-negative or equivocal results (67, 68). |

| Confirmatory test . | Procedure . | Interpretation . | Concerns . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral sodium loading test | Patients should increase their sodium intake to >200 mmol/d (∼6 g/d) for 3 d, verified by 24-h urine sodium content. Patients should receive adequate slow-release potassium chloride supplementation to maintain plasma potassium in the normal range. Urinary aldosterone is measured in the 24-h urine collection from the morning of d 3 to the morning of d 4. | PA is unlikely if urinary aldosterone is lower than 10 μg/24 h (27.7 nmol/d) in the absence of renal disease where PA may coexist with lower measured urinary aldosterone levels. Elevated urinary aldosterone excretion [>12 μg/24 h (>33.3 nmol/d) at the Mayo Clinic, >14 μg/24 h (38.8 nmol/d) at the Cleveland Clinic] makes PA highly likely. | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. The 24-h urine collection may be inconvenient. Laboratory-specific poor performance of the RIA for urinary aldosterone (aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide or acid-labile metabolite) may blunt diagnostic accuracy, a problem obviated by the currently available HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry methodology (52). Aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide is a renal metabolite, and its excretion may not rise in patients with renal disease. |

| SIT | Patients stay in the recumbent position for at least 1 h before and during the infusion of 2 liters of 0.9% saline iv over 4 h, starting at 0800–0930 h. Blood samples for renin, aldosterone, cortisol, and plasma potassium are drawn at time zero and after 4 h, with blood pressure and heart rate monitored throughout the test. | Postinfusion plasma aldosterone levels <5 ng/dl make the diagnosis of PA unlikely, and levels >10 ng/dl are a very probable sign of PA. Values between 5 and 10 ng/dl are indeterminate (57–60). | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. |

| FST | Patients receive 0.1 mg oral fludrocortisone every 6 h for 4 d, together with slow-release KCl supplements (every 6 h at doses sufficient to keep plasma K+, measured four times a day, close to 4.0 mmol/liter), slow-release NaCl supplements (30 mmol three times daily with meals) and sufficient dietary salt to maintain a urinary sodium excretion rate of at least 3 mmol/kg body weight. On d 4, plasma aldosterone and PRA are measured at 1000 h with the patient in the seated posture, and plasma cortisol is measured at 0700 and 1000 h. | Upright plasma aldosterone >6 ng/dl on d 4 at 1000 h confirms PA, provided PRA is < 1 ng/ml·h and plasma cortisol concentration is lower than the value obtained at 0700 h (to exclude a confounding ACTH effect) (42, 43, 56, 61–63). | Although some centers (10, 16) conduct this test in the outpatient setting (provided that patients are able to attend frequently to monitor their potassium), in other centers, several days of hospitalization are customary. |

| Most of the data available come from the Brisbane group (42, 43, 56, 61–63) who have established, on the basis of a very large series of patients, a cutoff of a plasma aldosterone concentration of 6 ng/dl at 1000 h in an ambulatory patient on d 4. | |||

| Proponents of the FST argue that 1) it is the most sensitive for confirming PA, 2) it is a less intrusive method of sodium loading than SIT and therefore less likely to provoke non-renin-dependent alterations of aldosterone levels, 3) it allows for the potentially confounding effects of potassium to be controlled and for ACTH (via cortisol) to be monitored and detected, and 4) it is safe when performed by experienced hands. | |||

| Captopril challenge test | Patients receive 25–50 mg captopril orally after sitting or standing for at least 1 h. Blood samples are drawn for measurement of PRA, plasma aldosterone, and cortisol at time zero and at 1 or 2 h after challenge, with the patient remaining seated during this period. | Plasma aldosterone is normally suppressed by captopril (>30%). In patients with PA, it remains elevated and PRA remains suppressed. Differences may be seen between patients with APA and those with IHA, in that some decrease of aldosterone levels is occasionally seen in IHA (23, 64–66). | There are reports of a substantial number of false-negative or equivocal results (67, 68). |

| Confirmatory test . | Procedure . | Interpretation . | Concerns . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral sodium loading test | Patients should increase their sodium intake to >200 mmol/d (∼6 g/d) for 3 d, verified by 24-h urine sodium content. Patients should receive adequate slow-release potassium chloride supplementation to maintain plasma potassium in the normal range. Urinary aldosterone is measured in the 24-h urine collection from the morning of d 3 to the morning of d 4. | PA is unlikely if urinary aldosterone is lower than 10 μg/24 h (27.7 nmol/d) in the absence of renal disease where PA may coexist with lower measured urinary aldosterone levels. Elevated urinary aldosterone excretion [>12 μg/24 h (>33.3 nmol/d) at the Mayo Clinic, >14 μg/24 h (38.8 nmol/d) at the Cleveland Clinic] makes PA highly likely. | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. The 24-h urine collection may be inconvenient. Laboratory-specific poor performance of the RIA for urinary aldosterone (aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide or acid-labile metabolite) may blunt diagnostic accuracy, a problem obviated by the currently available HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry methodology (52). Aldosterone 18-oxo-glucuronide is a renal metabolite, and its excretion may not rise in patients with renal disease. |

| SIT | Patients stay in the recumbent position for at least 1 h before and during the infusion of 2 liters of 0.9% saline iv over 4 h, starting at 0800–0930 h. Blood samples for renin, aldosterone, cortisol, and plasma potassium are drawn at time zero and after 4 h, with blood pressure and heart rate monitored throughout the test. | Postinfusion plasma aldosterone levels <5 ng/dl make the diagnosis of PA unlikely, and levels >10 ng/dl are a very probable sign of PA. Values between 5 and 10 ng/dl are indeterminate (57–60). | This test should not be performed in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension, renal insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmia, or severe hypokalemia. |

| FST | Patients receive 0.1 mg oral fludrocortisone every 6 h for 4 d, together with slow-release KCl supplements (every 6 h at doses sufficient to keep plasma K+, measured four times a day, close to 4.0 mmol/liter), slow-release NaCl supplements (30 mmol three times daily with meals) and sufficient dietary salt to maintain a urinary sodium excretion rate of at least 3 mmol/kg body weight. On d 4, plasma aldosterone and PRA are measured at 1000 h with the patient in the seated posture, and plasma cortisol is measured at 0700 and 1000 h. | Upright plasma aldosterone >6 ng/dl on d 4 at 1000 h confirms PA, provided PRA is < 1 ng/ml·h and plasma cortisol concentration is lower than the value obtained at 0700 h (to exclude a confounding ACTH effect) (42, 43, 56, 61–63). | Although some centers (10, 16) conduct this test in the outpatient setting (provided that patients are able to attend frequently to monitor their potassium), in other centers, several days of hospitalization are customary. |

| Most of the data available come from the Brisbane group (42, 43, 56, 61–63) who have established, on the basis of a very large series of patients, a cutoff of a plasma aldosterone concentration of 6 ng/dl at 1000 h in an ambulatory patient on d 4. | |||

| Proponents of the FST argue that 1) it is the most sensitive for confirming PA, 2) it is a less intrusive method of sodium loading than SIT and therefore less likely to provoke non-renin-dependent alterations of aldosterone levels, 3) it allows for the potentially confounding effects of potassium to be controlled and for ACTH (via cortisol) to be monitored and detected, and 4) it is safe when performed by experienced hands. | |||

| Captopril challenge test | Patients receive 25–50 mg captopril orally after sitting or standing for at least 1 h. Blood samples are drawn for measurement of PRA, plasma aldosterone, and cortisol at time zero and at 1 or 2 h after challenge, with the patient remaining seated during this period. | Plasma aldosterone is normally suppressed by captopril (>30%). In patients with PA, it remains elevated and PRA remains suppressed. Differences may be seen between patients with APA and those with IHA, in that some decrease of aldosterone levels is occasionally seen in IHA (23, 64–66). | There are reports of a substantial number of false-negative or equivocal results (67, 68). |

2.1 Values

Confirmatory testing places a high value on sparing individuals with false-positive ARR tests costly and intrusive lateralization procedures.

2.1 Remarks

For each of the four confirmatory tests, procedures, interpretations, and concerns are described in Table 6.

3.0 Subtype Classification

3.1 We recommend that all patients with PA undergo an adrenal CT scan as the initial study in subtype testing and to exclude large masses that may represent adrenocortical carcinoma (Fig. 1). (1|⊕⊕OO)

3.1 Evidence

The findings on adrenal CT—normal-appearing adrenals, unilateral macroadenoma (>1 cm), minimal unilateral adrenal limb thickening, unilateral microadenomas (≤1 cm), or bilateral macro- or microadenomas (or a combination of the two)—are used in conjunction with AVS and, if needed, ancillary tests to guide treatment decisions in patients with PA. APA may be visualized as small hypodense nodules (usually <2 cm in diameter) on CT. IHA adrenal glands may be normal on CT or show nodular changes. Aldosterone-producing adrenal carcinomas are almost always more than 4 cm in diameter, but occasionally smaller, and like most adrenocortical carcinomas have a suspicious imaging phenotype on CT (69).

Adrenal CT has several limitations. Small APAs may be interpreted incorrectly by the radiologist as IHA on the basis of CT findings of bilateral nodularity or normal-appearing adrenals. Moreover, apparent adrenal microadenomas may actually represent areas of hyperplasia, and unilateral adrenalectomy would be inappropriate. In addition, nonfunctioning unilateral adrenal macroadenomas are not uncommon, especially in older patients (>40 yr) (70) and are indistinguishable from APAs on CT. Unilateral UAH may be visible on CT, or the UAH adrenal may appear normal on CT.

In one study, CT contributed to lateralization in only 59 of 111 patients with surgically proven APA; CT detected fewer than 25% of the APAs that were smaller than 1 cm in diameter (62). In another study of 203 patients with PA who were evaluated with both CT and AVS, CT was accurate in only 53% of patients (71). On the basis of CT findings, 42 patients (22%) would have been incorrectly excluded as candidates for adrenalectomy, and 48 (25%) might have had unnecessary or inappropriate surgery (71). In a recent study, AVS was performed in 41 patients with PA, and concordance between CT and AVS was only 54% (72). Therefore, AVS is essential to direct appropriate therapy in patients with PA who seek a potential surgical cure. CT is particularly useful, however, for detecting larger lesions (e.g. >2.5 cm) that may warrant consideration for removal based on malignant potential and also for localizing the right adrenal vein as it enters into the inferior vena cava (IVC), thus aiding cannulation of the vein during AVS (73, 74).

3.1 Remarks

Magnetic resonance imaging has no advantage over CT in subtype evaluation of PA, being more expensive and having less spatial resolution than CT.

3.2 We recommend that, when surgical treatment is practicable and desired by the patient, the distinction between unilateral and bilateral adrenal disease be made by AVS by an experienced radiologist (Fig. 1). (1|⊕⊕⊕O)

Evidence

Lateralization of the source of the excessive aldosterone secretion is critical to guide the management of PA. Distinguishing between unilateral and bilateral disease is important because unilateral adrenalectomy in patients with APA or UAH results in normalization of hypokalemia in all; hypertension is improved in all and cured in 30–60% (46, 75, 76). In bilateral IHA and GRA, unilateral or bilateral adrenalectomy seldom corrects the hypertension (77–81), and medical therapy is the treatment of choice (82). Unilateral disease may be treated medically if the patient declines or is not a candidate for surgery.

Imaging cannot reliably visualize microadenomas or distinguish incidentalomas from APAs with confidence (71), making AVS the most accurate means of differentiating unilateral from bilateral forms of PA. AVS is expensive and invasive, and so it is highly desirable to avoid this test in patients who do not have PA (83). Because ARR testing can be associated with false positives, confirmatory testing should eliminate the potential for patients with false-positive ARR to undergo AVS.

The sensitivity and specificity of AVS (95 and 100%, respectively) for detecting unilateral aldosterone excess are superior to that of adrenal CT (78 and 75%, respectively) (62, 71, 72). Importantly, CT has the potential to be frankly misleading by demonstrating unilateral nodules in patients with bilateral disease and thereby to lead to inappropriate surgery.

AVS is the reference standard test to differentiate unilateral (APA or UAH) from bilateral (IHA) disease in patients with PA (62, 71). Although AVS can be a difficult procedure, especially in terms of successfully cannulating the right adrenal vein (which is smaller than the left and usually empties directly into the IVC rather than the renal vein), the success rate usually improves quickly as the angiographer becomes more experienced. According to a review of 47 reports, the success rate for cannulating the right adrenal vein in 384 patients was 74% (82). With experience, the success rate increased to 90–96% (71, 73, 74, 84). The addition of rapid intraprocedural measurement of adrenal vein cortisol concentrations has facilitated improved accuracy of catheter placement in AVS (85). Some centers perform AVS in all patients who have the diagnosis of PA (62), and others advocate its selective use (e.g. AVS may not be needed in patients younger than age 40 with solitary unilateral apparent adenoma on CT scan) (71, 86).

At centers with experienced AVS radiologists, the complication rate is 2.5% or lower (71, 73). The risk of adrenal hemorrhage can be minimized by employing a radiologist skilled in the technique and by avoiding adrenal venography and limiting use of contrast to the smallest amounts necessary to assess the catheter tip position (74). Where there is a clinical suspicion of a procoagulant disorder, the risk of thromboembolism may be reduced by performing tests for such conditions before the procedure and administering heparin after the procedure in patients at risk.

3.2 Values

Our recommendation to pursue AVS in the subtype evaluation of the patient with PA who is a candidate for surgery places a high value on avoiding the risk of an unnecessary unilateral adrenalectomy based on adrenal CT and a relatively low value on avoiding the potential complications of AVS.

3.2 Remarks

A radiologist experienced with and dedicated to AVS is needed to implement this recommendation.

There are three protocols for AVS: 1) unstimulated sequential or simultaneous bilateral AVS, 2) unstimulated sequential or simultaneous bilateral AVS followed by bolus cosyntropin-stimulated sequential or simultaneous bilateral AVS, and 3) continuous cosyntropin infusion with sequential bilateral AVS. Simultaneous bilateral AVS is difficult to perform and is not used at most centers. Many groups advocate the use of continuous cosyntropin infusion during AVS 1) to minimize stress-induced fluctuations in aldosterone secretion during nonsimultaneous (sequential) AVS, 2) to maximize the gradient in cortisol from adrenal vein to IVC and thus confirm successful sampling of the adrenal vein, and 3) to maximize the secretion of aldosterone from an APA (71, 81, 84, 87) and thus avoid the risk of sampling during a relatively quiescent phase of aldosterone secretion.

The criteria used to determine lateralization of aldosterone hypersecretion depend on whether the sampling is done under cosyntropin administration. Dividing the right and left adrenal vein PACs by their respective cortisol concentrations corrects for dilutional effects of the inferior phrenic vein flowing into the left adrenal vein and, if suboptimally sampled, of IVC flow into the right adrenal vein. These are termed cortisol-corrected aldosterone ratios. With continuous cosyntropin administration, a cutoff of the cortisol-corrected aldosterone ratio from high side to low side more than 4:1 is used to indicate unilateral aldosterone excess (71); a ratio less than 3:1 is suggestive of bilateral aldosterone hypersecretion (71). With these cutoffs, AVS for detecting unilateral aldosterone hypersecretion (APA or UAH) has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 100% (71). Patients with lateralization ratios between 3:1 and 4:1 may have either unilateral or bilateral disease, and the AVS results must be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical setting, CT scan, and ancillary tests.