-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sherita Hill Golden, Joshua J Joseph, Felicia Hill-Briggs, Casting a Health Equity Lens on Endocrinology and Diabetes, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 106, Issue 4, April 2021, Pages e1909–e1916, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa938

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

As endocrinologists we have focused on biological contributors to disparities in diabetes, obesity and other endocrine disorders. Given that diabetes is an exemplar health disparity condition, we, as a specialty, are also positioned to view the contributing factors and solutions more broadly. This will give us agency in contributing to health system, public health, and policy-level interventions to address the structural and institutional racism embedded in our medical and social systems. A history of unconsented medical and research experimentation on vulnerable groups and perpetuation of eugenics theory in the early 20th century have resulted in residual health care provider biases toward minority patients and patient distrust of medical systems, leading to poor quality of care. Historical discriminatory housing and lending policies resulted in racial residential segregation and neighborhoods with inadequate housing, healthy food access, and educational resources, setting the foundation for the social determinants of health (SDOH) contributing to present-day disparities. To reduce these disparities we need to ensure our health systems are implementing the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care to promote health equity. Because of racial biases inherent in our medical systems due to historical unethical practices in minority communities, health care provider training should incorporate awareness of unconscious bias, antiracism, and the value of diversity. Finally, we must also address poverty-related SDOH (eg, food and housing insecurity) by integrating social needs into medical care and using our voices to advocate for social policies that redress SDOH and restore environmental justice.

The Endocrine Society’s inaugural scientific statement on Health Disparities in Endocrine Disorders, published in 2012, highlighted the state of disparities and recommended future research needs in the areas of diabetes and its complications, gestational diabetes, thyroid disorders, osteoporosis/metabolic bone disease, and vitamin D deficiency (1). The statement emphasized the need for more basic science, clinical, and translational research to identify biological and nonbiological factors contributing to disparities in these conditions in non-White populations (1). The statement featured specific recommendations including increased vitamin D supplementation in non-Hispanic Blacks and increased osteoporosis screening, diagnosis, and treatment in minority women (to prevent fractures and their associated morbidities). The statement also recommended development of effective health care interventions to address and reduce racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes incidence, complications, and mortality (1).

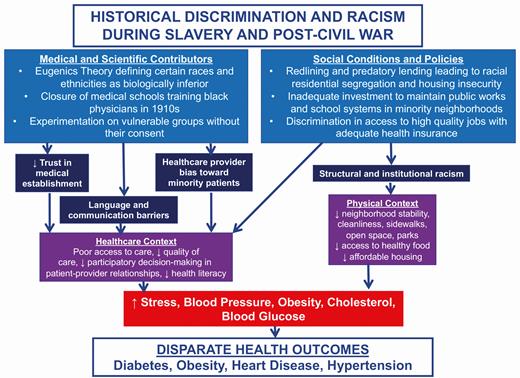

As a specialty our focus has been on the biology of metabolic disease risk—pathophysiological pathways and responses that lead to obesity, diabetes, metabolic bone disease, and thyroid disease. But what if our call is even broader—to take a step back and ask the question: “Why are we seeing these biological responses leading to higher metabolic disease risk and poorer outcomes in minority populations?” We acknowledge, as was highlighted in the 2012 scientific statement, that minority populations are less likely to have adequate health insurance or access to high-quality health care, resulting in poorer health outcomes and health inequity. But why does this disparity exist? As a specialty, given that diabetes is an exemplar health disparity disease, we are positioned to view the contributing factors and solutions more broadly and contribute to health system, public health, and policy-level interventions to address the historical root causes embedded in our medical and social systems (Fig. 1) (2). While we will focus on African Americans in this Perspective, we acknowledge that other minoritized populations (eg, Latinx/Hispanic, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, individuals with disabilities) also experience health inequities in diabetes and endocrine disorders.

Medical, scientific, and social policy contributors to health and health care disparities in African Americans in the United States.

Historical Medical and Scientific Contributors to Health Disparities

There are several historical contributors to health disparities in the African American population. During slavery it was not uncommon for slaves to be subjected to medical experimentation and to have surgical procedures performed against their will and without anesthesia (3). This has led to biased beliefs among health care providers that Black patients have higher pain tolerance than White patients (4). Even in the post–Civil War era African Americans continued to be subjects of experimentation without their consent. In 1910 the landmark Flexner Report was released, which transformed medical education by eliminating proprietary schools and establishing the biomedical model as the gold standard of medical training (5), resulting in the closure of a significant number of medical schools across the country. This had a profound effect on schools training Black physicians, as 5 of the 7 medical schools in the country devoted to Black physician education were closed. Following the Flexner Report, only Howard University in Washington, DC, and Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, remained to train Black physicians at a time when they could not gain access to predominantly White medical schools because of legal racial segregation and discrimination (5). Consequently, there was a dearth of Black medical professionals to care for African American communities across the United States and to protect the population from unethical practices, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, a government-funded 40-year observational study in which African American men were denied treatment for syphilis (6). This closure of historically Black medical schools also led to a lasting legacy of underrepresentation of Black medical professionals in the biomedical workforce. Although there are now protections and required consent for individuals participating in research and entering medical care, these prior abuses have led to persisting degrees of distrust of the medical establishment within African American communities, contributing an additional layer to the structural barriers that impede early and routine care access and treatment engagement.

At the turn of the 20th century, eugenics theory evolved, defining certain racial and ethnic groups as biologically inferior to the White race. This imposed biological hierarchy was used to justify the unconsented experimentation on African Americans as well as other vulnerable populations (eg, immigrants, prisoners, those institutionalized and hospitalized for mental and/or physical disabilities). Although eugenics has been scientifically refuted (7), the negative beliefs and stereotypes about race are embedded in our culture and contribute to ongoing health care provider bias toward African American patients (8). Black patients are viewed as less intelligent, less able to adhere to treatment recommendations, and more likely to engage in risky health behaviors compared to White patients (9). Studies assessing bias using the Implicit Association Test have demonstrated pro-White/light-skin and anti-Black/dark-skin bias among a variety of health care providers across multiple levels of training and disciplines (10). These biases are associated with disparities in treatment recommendations, expectations of therapy adherence, pain management and empathy (10). This also leads to fewer patient-centered clinical interactions with more verbal dominance by the provider, as well as to decreased participatory decision making in the patient-provider relationship, and less effective care (9, 11, 12). Quality of care is also impaired when there is inadequate infrastructure in our health care systems to address language and communication barriers as well as poor health literacy. The importance of this challenge will only increase with the rise of telehealth use during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (13).

Historical Social Conditions and Policy Contributors to Health Disparities

Discriminatory policies in the post–Civil War era created structural and institutional racism leading to poor social and living conditions for African Americans in the United States. Federal, state, and local laws during the 1900s prohibited African Americans from living in suburban neighborhoods and segregated them and other minoritized populations to urban housing projects (14). Subsequent laws defunded urban jurisdictions and imposed zoning restrictions, resulting in further inequities in resources (eg, education, employment, recreation, supermarkets) (14, 15).

As African Americans migrated from the South to cities further north, Whites left and moved to other sections of cities. To facilitate the rapid conversion of these areas to all-Black neighborhoods (known as “block busting”), African Americans who sought their own homes were subject to denials based on race and to predatory lending practices making them more likely to default on their loans (16). In 1933, the government instituted “redlining,” the policy that furthered segregation by the Federal Housing Administration’s refusing to ensure mortgages anywhere African Americans lived, based on the assertion that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities (17).” This gave federal support to racist real-estate practices in cities from Chicago, Illinois, to Baltimore, Maryland. The consequences of these actions resulted in racial residential segregation and inadequate investment in these neighborhoods, which were now all Black, to maintain public works, school systems, and economic development (16). African Americans were unable to move to better neighborhoods because of racial discrimination, backed by federal policy to deny home loans, which remained legal until the 1968 Civil Rights Act was signed into law. These policies resulted in structural and institutional racism with residual present-day effects. These include racial residential segregation; neighborhoods with inadequate affordable housing, security, cleanliness, sidewalks, open spaces, parks, and healthy food access; and increased exposure to environmental pollutants (8). These important social determinants of health contribute to poor health for the African Americans and other minoritized populations who live in these neighborhoods, promoting decreased physical activity and access to healthy food, consequently leading to increased rates of obesity and diabetes.

Disparities in Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Diabetes

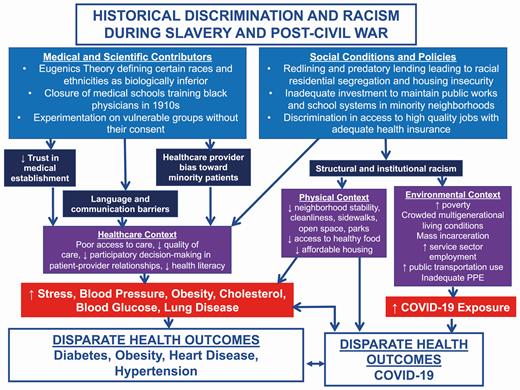

The COVID-19 pandemic has evidenced the breadth and depth of health disparities in the United States. Very early in the pandemic diabetes and obesity were identified as risk factors for a more severe coronavirus infection and a greater likelihood of mortality. In a study by Geiss et al published in 2014, during a time period when diabetes incidence had begun to decline in White Americans, it unfortunately continued to rise in African Americans and other minoritized groups (18). Consequently, a higher prevalence of diabetes among African Americans has predisposed them to poor outcomes and high mortality from COVID-19 infection. In addition to greater diabetes risk in African Americans because of the longstanding inequities in medical care, social conditions, and policies outlined earlier, they have also had increased exposure to COVID-19. Their disproportionate employment in essential jobs in the service sector that required in-person work (eg, transportation, environmental services, food services), housing insecurity leading many to live in crowded housing with an inability to socially distance, reliance on public transportation, and mass incarceration of African American men in crowded and unsanitary conditions have all contributed to higher exposure rates (8). Unfortunately these complex circumstances have created a scenario in which African Americans who already have a high burden of chronic metabolic conditions that portend a poor outcome are also more likely to be contract COVID-19 and die (Fig. 2) (2).

Medical, scientific, and social policy contributors to health, health care, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) disparities in African Americans in the United States.

Health System Approaches to Reduce Endocrine Disparities—National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care

The United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health has established national culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) standards to guide health care organizations in achieving and promoting health equity and reducing health and health care disparities (Table 1) (2, 19). These standards require health care organizations to establish culturally and linguistically appropriate goals, policies and accountability that are incorporated into an organization’s clinical operations with a plan for evaluation, continuous quality improvement, and accountability (19). To achieve health equity it is important to collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate disease outcomes based on race, ethnicity, sex, English proficiency, ability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity (another CLAS recommendation). Health care organizations need to train their staff in the proper interview techniques to ascertain patients’ self-identified race, ethnicity, and preferred language for health care and their sexual orientation and gender identity, which also includes pronouns. Given the high prevalence of functional impairment and disabilities among patients with diabetes (20, 21), this information will enable the health care team to provide proper assistance to patients so they can fully engage in their care (eg, sign language interpretation, mobility devices, low-vision support, mental health services). Another important aspect of the CLAS standards is providing language assistance to those with limited English proficiency and/or other communication needs. Among limited English proficiency (LEP) Latinos with diabetes, those who switched from a non–language-concordant primary care provider to one who was language concordant (ie, Spanish-speaking) had significant improvement in glycemic and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol control (22). Therefore, language-concordant care, which can be facilitated by providing certified interpretation services for LEP individuals, is a critical element of delivering equitable care. It is also critical to provide easy-to-understand patient education materials and signage in clinical areas in the most commonly spoken languages for the population served by a health care institution (19).

National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care (National CLAS Standards) (18)

| CLAS standard category . | Standard elements . | Recommended approaches . |

|---|---|---|

| Principal standard | 1. Provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs. | |

| Governance, leadership, and workforce | 2. Advance and sustain organizational governance and leadership that promotes CLAS and health equity through policy, practices, and allocated resources. | - Diversify the endocrine workforce with culturally competent and bilingual providers - Support pathway programs to engage underrepresented students in applying to medical and graduate school - Mandate system-wide health care provider education that includes unconscious bias, diversity awareness, and antiracism training |

| 3. Recruit, promote, and support a culturally and linguistically diverse governance, leadership and workforce that are responsive to the population in the service area. | ||

| 4. Educate and train governance, leadership, and workforce in culturally and linguistically appropriate policies and practices on an ongoing basis. | ||

| Communication and language assistance | 5. Offer language assistance to individuals who have limited English proficiency and/or other communication needs, at no cost to them, to facilitate timely access to all health care and services. | - Establish robust language access services program using certified bilingual providers and interpretation services using multiple modalities (in-person, telephone, video remote) - Ensure that patient education materials are literacy-adapted and easy to understand. - Provide patient education materials and clinical area signage in most commonly spoken languages. |

| 6. Inform all individuals of the availability of language assistance services clearly and in their preferred language, verbally and in writing. | ||

| 7. Ensure the competence of individuals providing language assistance, recognizing that the use of untrained individuals and/or minors as interpreters should be avoided. | ||

| 8. Provide easy-to-understand print and multimedia materials and signage in the languages commonly used by the populations in the service area. | ||

| Engagement, continuous improvement, and accountability | 9. Establish culturally and linguistically appropriate goals, policies and management accountability, and infuse them throughout the organizations’ planning and operations. | - Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate disease outcome by race, ethnicity, sex, English proficiency, ability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity. - Train staff in proper interview techniques to ascertain patients’ self-identified demographic data. - Create and regularly monitor health equity dashboards as part of organizational quality improvement activities. - Incorporate multilevel, culturally tailored, and literacy-adapted interventions that target all aspects of health care delivery—patients, providers, and health care system |

| 10. Conduct ongoing assessments of the organization’s CLAS-related activities and integrate CLAS-related measures into assessment measurement and continuous quality improvement activities. | ||

| 11. Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate the impact of CLAS on health equity and outcomes and inform service delivery. | ||

| 12. Conduct regular assessments of community health assets and needs and use the results to plan and implement services that respond to the culturally and linguistic diversity of populations in the service area. | ||

| 13. Partner with the community to design, implement, and evaluate policies, practices, and services to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness. | ||

| 14. Create conflict- and grievance-resolution processes that are culturally and linguistically appropriate to identify, prevent, and resolve conflicts or complaints. | ||

| 15. Communicate the organization’s progress in implementing and sustaining CLAS to all stakeholders, constituents and the general public. |

| CLAS standard category . | Standard elements . | Recommended approaches . |

|---|---|---|

| Principal standard | 1. Provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs. | |

| Governance, leadership, and workforce | 2. Advance and sustain organizational governance and leadership that promotes CLAS and health equity through policy, practices, and allocated resources. | - Diversify the endocrine workforce with culturally competent and bilingual providers - Support pathway programs to engage underrepresented students in applying to medical and graduate school - Mandate system-wide health care provider education that includes unconscious bias, diversity awareness, and antiracism training |

| 3. Recruit, promote, and support a culturally and linguistically diverse governance, leadership and workforce that are responsive to the population in the service area. | ||

| 4. Educate and train governance, leadership, and workforce in culturally and linguistically appropriate policies and practices on an ongoing basis. | ||

| Communication and language assistance | 5. Offer language assistance to individuals who have limited English proficiency and/or other communication needs, at no cost to them, to facilitate timely access to all health care and services. | - Establish robust language access services program using certified bilingual providers and interpretation services using multiple modalities (in-person, telephone, video remote) - Ensure that patient education materials are literacy-adapted and easy to understand. - Provide patient education materials and clinical area signage in most commonly spoken languages. |

| 6. Inform all individuals of the availability of language assistance services clearly and in their preferred language, verbally and in writing. | ||

| 7. Ensure the competence of individuals providing language assistance, recognizing that the use of untrained individuals and/or minors as interpreters should be avoided. | ||

| 8. Provide easy-to-understand print and multimedia materials and signage in the languages commonly used by the populations in the service area. | ||

| Engagement, continuous improvement, and accountability | 9. Establish culturally and linguistically appropriate goals, policies and management accountability, and infuse them throughout the organizations’ planning and operations. | - Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate disease outcome by race, ethnicity, sex, English proficiency, ability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity. - Train staff in proper interview techniques to ascertain patients’ self-identified demographic data. - Create and regularly monitor health equity dashboards as part of organizational quality improvement activities. - Incorporate multilevel, culturally tailored, and literacy-adapted interventions that target all aspects of health care delivery—patients, providers, and health care system |

| 10. Conduct ongoing assessments of the organization’s CLAS-related activities and integrate CLAS-related measures into assessment measurement and continuous quality improvement activities. | ||

| 11. Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate the impact of CLAS on health equity and outcomes and inform service delivery. | ||

| 12. Conduct regular assessments of community health assets and needs and use the results to plan and implement services that respond to the culturally and linguistic diversity of populations in the service area. | ||

| 13. Partner with the community to design, implement, and evaluate policies, practices, and services to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness. | ||

| 14. Create conflict- and grievance-resolution processes that are culturally and linguistically appropriate to identify, prevent, and resolve conflicts or complaints. | ||

| 15. Communicate the organization’s progress in implementing and sustaining CLAS to all stakeholders, constituents and the general public. |

National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care (National CLAS Standards) (18)

| CLAS standard category . | Standard elements . | Recommended approaches . |

|---|---|---|

| Principal standard | 1. Provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs. | |

| Governance, leadership, and workforce | 2. Advance and sustain organizational governance and leadership that promotes CLAS and health equity through policy, practices, and allocated resources. | - Diversify the endocrine workforce with culturally competent and bilingual providers - Support pathway programs to engage underrepresented students in applying to medical and graduate school - Mandate system-wide health care provider education that includes unconscious bias, diversity awareness, and antiracism training |

| 3. Recruit, promote, and support a culturally and linguistically diverse governance, leadership and workforce that are responsive to the population in the service area. | ||

| 4. Educate and train governance, leadership, and workforce in culturally and linguistically appropriate policies and practices on an ongoing basis. | ||

| Communication and language assistance | 5. Offer language assistance to individuals who have limited English proficiency and/or other communication needs, at no cost to them, to facilitate timely access to all health care and services. | - Establish robust language access services program using certified bilingual providers and interpretation services using multiple modalities (in-person, telephone, video remote) - Ensure that patient education materials are literacy-adapted and easy to understand. - Provide patient education materials and clinical area signage in most commonly spoken languages. |

| 6. Inform all individuals of the availability of language assistance services clearly and in their preferred language, verbally and in writing. | ||

| 7. Ensure the competence of individuals providing language assistance, recognizing that the use of untrained individuals and/or minors as interpreters should be avoided. | ||

| 8. Provide easy-to-understand print and multimedia materials and signage in the languages commonly used by the populations in the service area. | ||

| Engagement, continuous improvement, and accountability | 9. Establish culturally and linguistically appropriate goals, policies and management accountability, and infuse them throughout the organizations’ planning and operations. | - Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate disease outcome by race, ethnicity, sex, English proficiency, ability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity. - Train staff in proper interview techniques to ascertain patients’ self-identified demographic data. - Create and regularly monitor health equity dashboards as part of organizational quality improvement activities. - Incorporate multilevel, culturally tailored, and literacy-adapted interventions that target all aspects of health care delivery—patients, providers, and health care system |

| 10. Conduct ongoing assessments of the organization’s CLAS-related activities and integrate CLAS-related measures into assessment measurement and continuous quality improvement activities. | ||

| 11. Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate the impact of CLAS on health equity and outcomes and inform service delivery. | ||

| 12. Conduct regular assessments of community health assets and needs and use the results to plan and implement services that respond to the culturally and linguistic diversity of populations in the service area. | ||

| 13. Partner with the community to design, implement, and evaluate policies, practices, and services to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness. | ||

| 14. Create conflict- and grievance-resolution processes that are culturally and linguistically appropriate to identify, prevent, and resolve conflicts or complaints. | ||

| 15. Communicate the organization’s progress in implementing and sustaining CLAS to all stakeholders, constituents and the general public. |

| CLAS standard category . | Standard elements . | Recommended approaches . |

|---|---|---|

| Principal standard | 1. Provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs. | |

| Governance, leadership, and workforce | 2. Advance and sustain organizational governance and leadership that promotes CLAS and health equity through policy, practices, and allocated resources. | - Diversify the endocrine workforce with culturally competent and bilingual providers - Support pathway programs to engage underrepresented students in applying to medical and graduate school - Mandate system-wide health care provider education that includes unconscious bias, diversity awareness, and antiracism training |

| 3. Recruit, promote, and support a culturally and linguistically diverse governance, leadership and workforce that are responsive to the population in the service area. | ||

| 4. Educate and train governance, leadership, and workforce in culturally and linguistically appropriate policies and practices on an ongoing basis. | ||

| Communication and language assistance | 5. Offer language assistance to individuals who have limited English proficiency and/or other communication needs, at no cost to them, to facilitate timely access to all health care and services. | - Establish robust language access services program using certified bilingual providers and interpretation services using multiple modalities (in-person, telephone, video remote) - Ensure that patient education materials are literacy-adapted and easy to understand. - Provide patient education materials and clinical area signage in most commonly spoken languages. |

| 6. Inform all individuals of the availability of language assistance services clearly and in their preferred language, verbally and in writing. | ||

| 7. Ensure the competence of individuals providing language assistance, recognizing that the use of untrained individuals and/or minors as interpreters should be avoided. | ||

| 8. Provide easy-to-understand print and multimedia materials and signage in the languages commonly used by the populations in the service area. | ||

| Engagement, continuous improvement, and accountability | 9. Establish culturally and linguistically appropriate goals, policies and management accountability, and infuse them throughout the organizations’ planning and operations. | - Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate disease outcome by race, ethnicity, sex, English proficiency, ability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity. - Train staff in proper interview techniques to ascertain patients’ self-identified demographic data. - Create and regularly monitor health equity dashboards as part of organizational quality improvement activities. - Incorporate multilevel, culturally tailored, and literacy-adapted interventions that target all aspects of health care delivery—patients, providers, and health care system |

| 10. Conduct ongoing assessments of the organization’s CLAS-related activities and integrate CLAS-related measures into assessment measurement and continuous quality improvement activities. | ||

| 11. Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate the impact of CLAS on health equity and outcomes and inform service delivery. | ||

| 12. Conduct regular assessments of community health assets and needs and use the results to plan and implement services that respond to the culturally and linguistic diversity of populations in the service area. | ||

| 13. Partner with the community to design, implement, and evaluate policies, practices, and services to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness. | ||

| 14. Create conflict- and grievance-resolution processes that are culturally and linguistically appropriate to identify, prevent, and resolve conflicts or complaints. | ||

| 15. Communicate the organization’s progress in implementing and sustaining CLAS to all stakeholders, constituents and the general public. |

Collecting accurate and reliable demographic data into a health equity dashboard allows organizations to identify where disparities exist in disease outcomes for the populations it serves, but are there effective interventions to reduce those disparities? Health services research in the field of diabetes has demonstrated the effectiveness of multilevel, culturally tailored interventions in improving diabetes outcomes for these vulnerable populations. Multilevel interventions target all aspects of health care delivery, including patients, providers, and the health care system. Features of effective interventions that improve glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) were cultural and health literacy tailored, led by community educators or lay people, 1:1 (vs group) interventions, incorporated treatment algorithms, focused on behavior-related tasks, and provided feedback and high-intensity interventions over a long duration (23). Interventions specific to health care organizations that have resulted in improved glycemic control for minority patients with diabetes include systems for rapid turnaround (eg, point of care) HbA1c, circumscribed appointments, support staff involvement (eg, nurse case management, community health worker, pharmacist), and enhanced follow-up with home visits or telephone/mail contact (23). These types of interventions fulfill national CLAS standard recommendations for incorporating CLAS-related activities and measures into an organization’s continuous quality improvement activities to achieve health equity.

National CLAS standards also call for recruiting and promoting a diverse and inclusive workforce to achieve health equity (19). According to 2018 data from the American Association of Medical Colleges, only 10.5% of endocrinologists and 12.6% of internists in the United States identify as being from groups underrepresented in medicine—Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander. These figures are startling given the high prevalence of diabetes in these populations. Thus, the 2 specialties caring for the majority of patients with diabetes lack a physician workforce reflecting this diverse population. It is crucial to diversify the endocrine workforce with physicians who are culturally competent and bilingual through robust diversity and inclusion efforts in our academic centers and health systems. Although efforts at the health system level are critical, health systems must also support pathway programs reaching back earlier in the pipeline to increase the diversity of medical school and graduate school applicants. Because of racial biases inherent in our medical systems due to historical unethical practices in minority communities, health care provider training should incorporate awareness of unconscious bias and antiracism (24), and the value of diversity. These efforts will repair historical harm, increase trust, provide tools to address structural racism in health care, and ultimately advance health equity.

Policy Recommendations to Address Social Determinants of Health

Poverty and racism are 2 upstream social determinants of health (SDOH) requiring mitigation to improve health outcomes. Within the walls of academic medical centers, we can affect discrimination, as a behavior resulting from racism, through our organizational human resources and clinical operations practices and policies. Additionally, we can begin to have an impact on poverty-related SDOH (eg, food insecurity, housing insecurity) through initiatives that align with national recommendations for integration of social needs into medical care (25). There is potential to affect the health care system components of the SDOH including equity in access to care and quality of care delivered through implementation of recommendations for educating health care professionals in SDOH, and through initiatives designed for health equity measurement and accountability (26).

Several examples exist of interventions that help to mitigate SDOH, including affordable housing development investment in Oakland, California, (27) and Geisinger’s Fresh Food Farmacy (28). Two intervention approaches are needed concurrently: interventions that compensate for the social determinant conditions under which people continue to live and root cause interventions to remove the SDOH altogether (29).

To have a lasting impact on the broader SDOH including economic stability, neighborhood and built environment, education, and food access, academic medical centers, as anchor organizations in their communities, must advocate for policies that directly redress the SDOH conditions in which people live and work. On behalf of people living with diabetes and other endocrine disorders, members of our specialty must become advocates for social policies that support environmental justice as necessary for the attainment of health equity. Through partnerships with the Government Affairs Offices at our local academic institutions and Endocrine Society Advocacy, we can support the development of legislation to address housing and food insecurity, lack of access to physical activity options, and job insecurity so that everyone can attain their highest level of health. The job losses resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have shed light on the importance of insurance that is not dependent on employment, with millions of workers recently losing their jobs and insurance with downstream impacts of food and housing insecurity. Academic medical centers must harness their intellectual capital and meaningful partnerships to address the largest component of overall health, the social determinants of health.

Abbreviations:

- CLAS

culturally and linguistically appropriate services;

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019;

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c;

- LEP

limited English proficiency;

- SDOH

social determinants of health

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest and no financial disclosures to reveal and have no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article because no data sets were generated or analyzed during the present study.