-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jonna M E Männistö, Maleeha Maria, Joose Raivo, Teemu Kuulasmaa, Timo Otonkoski, Hanna Huopio, Markku Laakso, Clinical and Genetic Characterization of 153 Patients with Persistent or Transient Congenital Hyperinsulinism, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 4, April 2020, Pages e1686–e1694, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz271

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Major advances have been made in the genetics and classification of congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI).

To examine the genetics and clinical characteristics of patients with persistent and transient CHI.

A cross-sectional study with the register data and targeted sequencing of 104 genes affecting glucose metabolism.

Genetic and phenotypic data were collected from 153 patients with persistent (n = 95) and transient (n = 58) CHI diagnosed between 1972 and 2015. Of these, 86 patients with persistent and 58 with transient CHI participated in the analysis of the selected 104 genes affecting glucose metabolism, including 10 CHI-associated genes, and 9 patients with persistent CHI were included because of their previously confirmed genetic diagnosis.

Targeted next-generation sequencing results and genotype–phenotype associations.

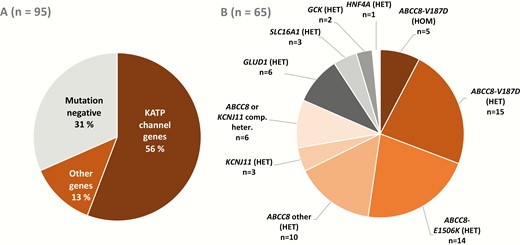

Five novel and 21 previously reported pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in ABCC8, KCNJ11, GLUD1, GCK, HNF4A, and SLC16A1 genes were found in 68% (n = 65) and 0% of the patients with persistent and transient CHI, respectively. KATP channel mutations explained 82% of the mutation positive cases.

The genetic variants found in this nationwide CHI cohort are in agreement with previous studies, mutations in the KATP channel genes being the major causes of the disease. Pathogenic CHI-associated variants were not identified in patients who were both diazoxide responsive and able to discontinue medication within the first 4 months. Therefore, our results support the notion that genetic testing should be focused on patients with inadequate response or prolonged need for medication.

Congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI) is a rare genetically, clinically, and histologically heterogeneous disorder in which pancreatic β cells secrete increased amounts of insulin resulting in hypoglycemia (1, 2). CHI comprises persistent (P-CHI) and transient (T-CHI) cases, and it can be also related to certain syndromes (2).

Previously published studies show that 38% to 79% of P-CHI cases are associated with a pathogenic or likely pathogenic CHI-associated variant, and currently 14 genes are reported to be associate with CHI (ABCC8, KCNJ11, GCK, GLUD1, HNF4A, HNF1A, HADH, SLC16A1, UCP2, HK1, PGM1, PMM2, FOXA2, and CACNAD1) (3–7). Variants in the KATP channel genes ABCC8 and KCNJ11 account for most cases of P-CHI for which a genetic cause has been identified. P-CHI is further classified into 4 distinct subgroups, (1) recessive diazoxide-responsive, (2) dominant diazoxide-responsive, (3) dominant diazoxide-unresponsive, and (4) focal CHI caused by uniparental disomy, resulting from a somatic loss of maternal allele in chromosome region 11p15 (1, 8). We have previously shown that the 2 founder mutations in the KATP channel gene, ABCC8/p.Val187Asp and ABCC8/p.Glu1506Lys, explain 58% of all P-CHI cases (9, 10). A recessive p.Val187Asp variant results in a more severe, typically diazoxide-unresponsive disease, and a dominant p.Glu1506Lys variant results in a relatively mild form of CHI (9, 10).

T-CHI is typically associated with maternal gestational diabetes or perinatal stress, and is usually resolved within weeks after birth, but it may also be severe and last up to few months and hence resemble the clinical course of P-CHI (11, 12).

Clinical symptoms of hypoglycemia appear usually during the neonatal period or early infancy. These include generalized (eg, hypothermia, hypotonia, or poor feeding) or neuroglycopenic symptoms (eg, lethargy, seizures), especially in the most severe cases (1, 2). Clinical manifestations of CHI can have a wide spectrum, and, therefore, the identification of the persistent form of the disease from other causes of neonatal hypoglycemia may be challenging. Genetic testing has been suggested for patients who do not respond, who need a high dose, or have a prolonged need for diazoxide (13). The genetic diagnosis may have an important role when planning the treatment, especially in the patients with paternal KATP channel gene variant and focal form of CHI, which can be cured by localized resection of pancreas.

In the present study, we investigated the genetic etiology and the genotype–phenotype associations in a nationwide cohort of patients with CHI.

Material and Methods

Study participants

The study cohort was recruited from the national CHI registry of 238 patients in Finland (P-CHI, n = 106; T-CHI, n = 132). The patients were identified by a diagnosis-based search for “other” or “unspecified hypoglycemia”, including hyperinsulinism (International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-8 from 1969, ICD-9 from 1987, and ICD-10 from 1996) of the hospital registries from all 5 Finnish University Hospitals and 14 central hospitals. These patients are likely to represent all affected individuals diagnosed in Finland during that time, although the possibility of undiagnosed cases especially in the 1970s and 1980s cannot be excluded.

The inclusion criteria for the registry and the current study were the diagnosis of CHI based on a combination of diagnostic findings of prolonged or recurrent hypoglycemia and signs of inappropriate insulin secretion: detectable serum insulin level and/or low free fatty acids during nonketotic hypoglycemia. The increased need for intravenous glucose (>8 mg/kg/min) was used as a supportive criterion in neonatal cases. Only patients who needed medication for hyperinsulinism (diazoxide or octreotide, which were used as alternatives for each other) were included. The definition of hypoglycemia was based on the recommendations of the Pediatric Endocrine Society: ≤2.8 mmol/L (≤50 mg/dL) in the first 48 hours of life, and ≤3.3 mmol/L (≤60 mg/dL) thereafter (14).

Targeted sequencing of the selected 104 genes affecting glucose metabolism, including 10 CHI-associated genes (all supplementary material and figures are located in a digital research materials repository (15)), was offered to all registry patients. Some of the 94 other genes have rare variants which could potentially cause hypoglycemia and increased insulin levels, and over time lead to hyperglycemia. Of the whole registry, 86 patients with P-CHI and 58 patients with T-CHI were willing to participate. Additionally, 9 P-CHI patients whose genetic diagnosis was already available in the medical records were included. Hence, altogether 153 patients (P-CHI, n = 95; T-CHI, n = 58) diagnosed between the years 1972 and 2015 were included in this study. Participation rates were 90% (95 of 106) in the P-CHI group and 44% (58 of 132) in the T-CHI group. One parent of 5 patients and both parents of 1 patient were of non-Finnish origin, but all other participants (96%) were of Finnish origin.

For our study protocol, we classified the patients retrospectively into the T-CHI group, when hyperinsulinism was detected during the neonatal period (<28 days after birth), there was no need to increase the dosing of medication (mg/kg/d) after achieving remission, the medication was successfully discontinued within the first 4 months, that is, there was no evidence of recurrent hypoglycemia in blood glucose measurements by fingerprick tests or continuous glucose monitoring during or after medication. All other patients with a late onset, long duration of medication or surgical treatment were classified as having P-CHI.

Severe symptoms at onset referred to seizure or coma and mild symptoms to any other hypoglycemia symptoms. Diazoxide responsiveness was defined clinically, when an asymptomatic child had normal blood glucose levels and did not need intravenous glucose infusion.

Targeted next-generation sequencing

The gene panel included 10 CHI-associated genes published by the time of the genetic analysis and additionally selected 94 genes affecting glucose metabolism (15). Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples (P-CHI, n = 86; T-CHI, n = 58) by automated QIAcube System and QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kits (Qiagen Inc, CA, USA). HaloPlex Target Enrichment System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to capture regions of interest for next generation sequencing. Online design tool SureDesign (https://earray.chem.agilent.com/suredesign/) was used for capture probe design. Target regions consisted of exons, untranslated regions, and 10 bp flanking regions of 104 glucose metabolism associated genes from the RefSeq database (GRCh37/hg19), including 10 CHI-associated genes (ABCC8, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man®, OMIM: 600509; KCNJ11, OMIM: 600937; GCK, OMIM: 138079; GLUD1, OMIM: 138130; HNF4A, OMIM: 600281; HNF1A, OMIM: 142410; HADH, OMIM: 601609; SLC16A1, OMIM: 600682; UCP2, OMIM: 601693; and HK1, OMIM: 142600) (15). The total length of the target regions was 484566 kbp and involved 1418 regions. Design yielded 18 838 amplicons covering 481.37 kbp of target regions. Library preparation was performed using HaloPlex Target Enrichment Kit by following manufacturer’s instructions. Paired-end sequencing (2 × 300 bp) was performed on MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the MiSeq Reagent Kits v3 (600 cycles).

Data analysis and variant calling

An inhouse-developed analysis pipeline was used for the analysis of raw fastq files generated by the MiSeq-sequencer. Cutadapt (https://code.google.com/p/cutadapt/) software was used for Illumina sequencing adapter removal and read trimming. Reads shorter than 20 bp were abandoned. Remaining reads were mapped to human reference genome hg19 using BWA-MEM algorithm (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant calling (single nucleotide variants and indels) was performed using 4 different variant callers: GATK HaplotypeCaller (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/), SAMTools mpileup (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/), Atlas2 (http://sourceforge.net/projects/atlas2/), Platypus (https://bio.tools/platypus). All called variants were annotated using SnpEff (http://snpeff.sourceforge.net/), ANNOVAR (http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/), and multiple different public databases (eg, 1000 Genomes, dbSNP, ClinVar, and gnomAD). Variants had to meet the following criteria to be included in the downstream analysis: located within the exonic or splicing regions, have high or moderate effect on gene function, and have unknown or variant allele frequency below 2% in the 1000 genomes variant database. The alignments at variant positions were visually inspected using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (https://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/).

In silico analyses of genetic variants.

The pathogenicity of the variants was assessed according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association of Molecular Pathology (16). We classified the variants into 5 different groups (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign, benign) based on evidence population frequency of the variant, computational data, functional data, and segregation data. We used the following in silico programs to evaluate the pathogenicity of each variant: Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT) (17), Polymorphism Phenotyping2 (PolyPhen2), HumVar module (18), Mutation taster (19), and MutPred (20). In silico analysis of intronic, synonymous, and canonical splice-site variants on splicing was done by Alamut visual version 2.9, which is a commercial software from Interactive Biosoftware (alamut.interactive-biosoftware.com). Additionally, we searched for functional evidence for pathogenicity based from previously published studies. Only pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants are reported.

Variant validation.

All pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were validated by Sanger sequencing using BigDye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and analyzed by 3500XL Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, MA, USA) with 3500 data collection software 2. We performed sequence analysis using Chromas Lite 2.1.1 © 1998–2013, program from Technelysium Pty Ltd.

Ethical considerations.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All patients (and/or their parents) who participated in the genetic analysis, gave their written consent. The 9 patients with an available genetic diagnosis and without genetic analysis in this study were included based on the permission for registry study.

Results

Clinical characteristics.

Clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1 and the online repository (15). In P-CHI (n = 95) and T-CHI groups (n = 58), 56% and 64% of the subjects were males, the median age at the onset of hypoglycemia was 1 day (range 1 day to 8 years) and 1 day (1–2 days), and the median age at the start of medication was 17 days (1 day to 8 years), and 7 days (1–27 days), respectively. Altogether, 64% and 100% of the patients with P-CHI and T-CHI responded to diazoxide treatment. Of the 32 operated patients with P-CHI, 13 had partial resection for a focal or multifocal CHI and 19 near-total or total pancreatectomy.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with persistent congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI) (n = 95) and transient CHI (n = 58) according to the genetic variants.

| . | Persistent CHI . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | Transient CHI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | KATP channel variants . | . | . | . | . | GLUD1 . | GCK . | SLC16A1 . | HNF4A . | Persistent CHI Mutation negative . | Mutation negative . |

| . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HOM or CH) . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HET) . | ABCC8 p.E1506K . | ABCC8 other . | KCNJ11 . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | (HET or CH) . | (HET or CH) . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| n | 9 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 58 |

| Gender M/F, (%) | 33/67 | 53/47 | 50/50 | 46/54 | 75 /25 | 67/33 | 50/50 | 33/67 | 0/100 | 67/L33 | 64/36 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 36 (29–39) | 40 (36–42) | 38 (33–40) | 38 (36–41) | 37 (27–40) | 39 (37–41) | 40 (40–40) | 40 (39–41) | 39 | 39 (31–42) | 37 (31–41) |

| Preterm, % (n)a | 66.7 (6) | 13.3 (2) | 35.7 (5) | 18.2 (2) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 20.0 (6) | 44.8 (26) |

| Birth weight SDS | +2.5 (+0.4–6.6) | +0.5 (–2.4–2.3) | +1.4 (–0.4–4.5) | +2.3 (–0.5–7.2) | +2.4 (+0.7–6.1) | –2.6 (–2.9–0.8) | +1.7 (+1.7–1.7) | –0.4 (–1.6–0.9) | +1.7 | +0.4 (–3.3–3.9) | –1.2 (–3.9–4.6) |

| Large for gestational age, % (n)b | 66.7 (6) | 13.3. (2) | 50.0 (7) | 63.6 (7) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 10.0 (3) | 13.8 (8) |

| Neonatal onset, % (n) | 100.0 (7) | 66.7 (10) | 92.9 (13) | 90.9 (10) | 100.0 (4) | 16.7 (1) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 53.3 (16) | NA |

| Age at detection of hypoglycemia, d | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–203) | 1 (1–183) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 160 (27–219) | 1617 (1–3233) | 808 (616–931) | 43 | 42 (1–878) | NA |

| Severe symptoms at onset, % (n) | 33.3 (3) | 26.7 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (3) | 50.0 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 33.3 (10) | 0.0 (0) |

| Max iv-glucose rate, mg/ kg/minc | 14.5 (10.0–25.9) | 11.8 (4.0–21.0) | 9.0 (7.4–10.0) | 12.9 (8.3–15.8) | 16.3 (12.0–20.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14.1 (6.2–21.0) | 12.7 (5.1–20.0) |

| Plasma insulin during hypoglycemia, mU/L | 57 (25–531) | 24 (5–200) | 21 (2–140) | 21 (12–38) | 46 (30–106) | 28 (17–80) | 25 (25) | 74 (16–131) | 41 | 20 (5–60) | 16 (2–116) |

| Diazoxide, max dose, mg/ kg/d | 11.3 (6.3–34.0) | 13.2 (3.8–23.8) | 6.4 (3.3–15.6) | 14.0 (5.1–21.0) | 14.5 (11.4–17.6) | 10.0 (6.7–12.0) | NA | 6.7 (4.0–12.0) | 6.2 (NA) | 12.5 (4.4–22.0) | 9.5 (2.3–20.1) |

| Diazoxide-responsive, % (n)d | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 92.9 (13) | 63.6 (7) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 (6) | 50.0 (1) | 100.0 (3) | 100.0 (1) | 86.2 (25) | 100.0 (54) |

| Surgery, % (n) | 100.0 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 7.1 (1) | 36.4 (4) | 25.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 13.3 (4) | NA |

| . | Persistent CHI . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | Transient CHI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | KATP channel variants . | . | . | . | . | GLUD1 . | GCK . | SLC16A1 . | HNF4A . | Persistent CHI Mutation negative . | Mutation negative . |

| . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HOM or CH) . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HET) . | ABCC8 p.E1506K . | ABCC8 other . | KCNJ11 . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | (HET or CH) . | (HET or CH) . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| n | 9 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 58 |

| Gender M/F, (%) | 33/67 | 53/47 | 50/50 | 46/54 | 75 /25 | 67/33 | 50/50 | 33/67 | 0/100 | 67/L33 | 64/36 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 36 (29–39) | 40 (36–42) | 38 (33–40) | 38 (36–41) | 37 (27–40) | 39 (37–41) | 40 (40–40) | 40 (39–41) | 39 | 39 (31–42) | 37 (31–41) |

| Preterm, % (n)a | 66.7 (6) | 13.3 (2) | 35.7 (5) | 18.2 (2) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 20.0 (6) | 44.8 (26) |

| Birth weight SDS | +2.5 (+0.4–6.6) | +0.5 (–2.4–2.3) | +1.4 (–0.4–4.5) | +2.3 (–0.5–7.2) | +2.4 (+0.7–6.1) | –2.6 (–2.9–0.8) | +1.7 (+1.7–1.7) | –0.4 (–1.6–0.9) | +1.7 | +0.4 (–3.3–3.9) | –1.2 (–3.9–4.6) |

| Large for gestational age, % (n)b | 66.7 (6) | 13.3. (2) | 50.0 (7) | 63.6 (7) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 10.0 (3) | 13.8 (8) |

| Neonatal onset, % (n) | 100.0 (7) | 66.7 (10) | 92.9 (13) | 90.9 (10) | 100.0 (4) | 16.7 (1) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 53.3 (16) | NA |

| Age at detection of hypoglycemia, d | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–203) | 1 (1–183) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 160 (27–219) | 1617 (1–3233) | 808 (616–931) | 43 | 42 (1–878) | NA |

| Severe symptoms at onset, % (n) | 33.3 (3) | 26.7 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (3) | 50.0 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 33.3 (10) | 0.0 (0) |

| Max iv-glucose rate, mg/ kg/minc | 14.5 (10.0–25.9) | 11.8 (4.0–21.0) | 9.0 (7.4–10.0) | 12.9 (8.3–15.8) | 16.3 (12.0–20.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14.1 (6.2–21.0) | 12.7 (5.1–20.0) |

| Plasma insulin during hypoglycemia, mU/L | 57 (25–531) | 24 (5–200) | 21 (2–140) | 21 (12–38) | 46 (30–106) | 28 (17–80) | 25 (25) | 74 (16–131) | 41 | 20 (5–60) | 16 (2–116) |

| Diazoxide, max dose, mg/ kg/d | 11.3 (6.3–34.0) | 13.2 (3.8–23.8) | 6.4 (3.3–15.6) | 14.0 (5.1–21.0) | 14.5 (11.4–17.6) | 10.0 (6.7–12.0) | NA | 6.7 (4.0–12.0) | 6.2 (NA) | 12.5 (4.4–22.0) | 9.5 (2.3–20.1) |

| Diazoxide-responsive, % (n)d | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 92.9 (13) | 63.6 (7) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 (6) | 50.0 (1) | 100.0 (3) | 100.0 (1) | 86.2 (25) | 100.0 (54) |

| Surgery, % (n) | 100.0 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 7.1 (1) | 36.4 (4) | 25.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 13.3 (4) | NA |

Abbreviations: HOM, homozygous; HET, heterozygous; CH, compound heterozygous; P/LP, pathogenic/Likely pathogenic.

Categorical variables represented as percentage (%) and number (n) of the patients. Continuous variables represented as median (range) values.

aBorn before 37 gestational weeks; bbirth weight SDS >2.0; cin neonates; dwhen used.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with persistent congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI) (n = 95) and transient CHI (n = 58) according to the genetic variants.

| . | Persistent CHI . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | Transient CHI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | KATP channel variants . | . | . | . | . | GLUD1 . | GCK . | SLC16A1 . | HNF4A . | Persistent CHI Mutation negative . | Mutation negative . |

| . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HOM or CH) . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HET) . | ABCC8 p.E1506K . | ABCC8 other . | KCNJ11 . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | (HET or CH) . | (HET or CH) . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| n | 9 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 58 |

| Gender M/F, (%) | 33/67 | 53/47 | 50/50 | 46/54 | 75 /25 | 67/33 | 50/50 | 33/67 | 0/100 | 67/L33 | 64/36 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 36 (29–39) | 40 (36–42) | 38 (33–40) | 38 (36–41) | 37 (27–40) | 39 (37–41) | 40 (40–40) | 40 (39–41) | 39 | 39 (31–42) | 37 (31–41) |

| Preterm, % (n)a | 66.7 (6) | 13.3 (2) | 35.7 (5) | 18.2 (2) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 20.0 (6) | 44.8 (26) |

| Birth weight SDS | +2.5 (+0.4–6.6) | +0.5 (–2.4–2.3) | +1.4 (–0.4–4.5) | +2.3 (–0.5–7.2) | +2.4 (+0.7–6.1) | –2.6 (–2.9–0.8) | +1.7 (+1.7–1.7) | –0.4 (–1.6–0.9) | +1.7 | +0.4 (–3.3–3.9) | –1.2 (–3.9–4.6) |

| Large for gestational age, % (n)b | 66.7 (6) | 13.3. (2) | 50.0 (7) | 63.6 (7) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 10.0 (3) | 13.8 (8) |

| Neonatal onset, % (n) | 100.0 (7) | 66.7 (10) | 92.9 (13) | 90.9 (10) | 100.0 (4) | 16.7 (1) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 53.3 (16) | NA |

| Age at detection of hypoglycemia, d | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–203) | 1 (1–183) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 160 (27–219) | 1617 (1–3233) | 808 (616–931) | 43 | 42 (1–878) | NA |

| Severe symptoms at onset, % (n) | 33.3 (3) | 26.7 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (3) | 50.0 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 33.3 (10) | 0.0 (0) |

| Max iv-glucose rate, mg/ kg/minc | 14.5 (10.0–25.9) | 11.8 (4.0–21.0) | 9.0 (7.4–10.0) | 12.9 (8.3–15.8) | 16.3 (12.0–20.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14.1 (6.2–21.0) | 12.7 (5.1–20.0) |

| Plasma insulin during hypoglycemia, mU/L | 57 (25–531) | 24 (5–200) | 21 (2–140) | 21 (12–38) | 46 (30–106) | 28 (17–80) | 25 (25) | 74 (16–131) | 41 | 20 (5–60) | 16 (2–116) |

| Diazoxide, max dose, mg/ kg/d | 11.3 (6.3–34.0) | 13.2 (3.8–23.8) | 6.4 (3.3–15.6) | 14.0 (5.1–21.0) | 14.5 (11.4–17.6) | 10.0 (6.7–12.0) | NA | 6.7 (4.0–12.0) | 6.2 (NA) | 12.5 (4.4–22.0) | 9.5 (2.3–20.1) |

| Diazoxide-responsive, % (n)d | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 92.9 (13) | 63.6 (7) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 (6) | 50.0 (1) | 100.0 (3) | 100.0 (1) | 86.2 (25) | 100.0 (54) |

| Surgery, % (n) | 100.0 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 7.1 (1) | 36.4 (4) | 25.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 13.3 (4) | NA |

| . | Persistent CHI . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | Transient CHI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | KATP channel variants . | . | . | . | . | GLUD1 . | GCK . | SLC16A1 . | HNF4A . | Persistent CHI Mutation negative . | Mutation negative . |

| . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HOM or CH) . | ABCC8 p.V187D (HET) . | ABCC8 p.E1506K . | ABCC8 other . | KCNJ11 . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | (HET or CH) . | (HET or CH) . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| n | 9 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 58 |

| Gender M/F, (%) | 33/67 | 53/47 | 50/50 | 46/54 | 75 /25 | 67/33 | 50/50 | 33/67 | 0/100 | 67/L33 | 64/36 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 36 (29–39) | 40 (36–42) | 38 (33–40) | 38 (36–41) | 37 (27–40) | 39 (37–41) | 40 (40–40) | 40 (39–41) | 39 | 39 (31–42) | 37 (31–41) |

| Preterm, % (n)a | 66.7 (6) | 13.3 (2) | 35.7 (5) | 18.2 (2) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 20.0 (6) | 44.8 (26) |

| Birth weight SDS | +2.5 (+0.4–6.6) | +0.5 (–2.4–2.3) | +1.4 (–0.4–4.5) | +2.3 (–0.5–7.2) | +2.4 (+0.7–6.1) | –2.6 (–2.9–0.8) | +1.7 (+1.7–1.7) | –0.4 (–1.6–0.9) | +1.7 | +0.4 (–3.3–3.9) | –1.2 (–3.9–4.6) |

| Large for gestational age, % (n)b | 66.7 (6) | 13.3. (2) | 50.0 (7) | 63.6 (7) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 10.0 (3) | 13.8 (8) |

| Neonatal onset, % (n) | 100.0 (7) | 66.7 (10) | 92.9 (13) | 90.9 (10) | 100.0 (4) | 16.7 (1) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 53.3 (16) | NA |

| Age at detection of hypoglycemia, d | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–203) | 1 (1–183) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 160 (27–219) | 1617 (1–3233) | 808 (616–931) | 43 | 42 (1–878) | NA |

| Severe symptoms at onset, % (n) | 33.3 (3) | 26.7 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (3) | 50.0 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 33.3 (10) | 0.0 (0) |

| Max iv-glucose rate, mg/ kg/minc | 14.5 (10.0–25.9) | 11.8 (4.0–21.0) | 9.0 (7.4–10.0) | 12.9 (8.3–15.8) | 16.3 (12.0–20.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14.1 (6.2–21.0) | 12.7 (5.1–20.0) |

| Plasma insulin during hypoglycemia, mU/L | 57 (25–531) | 24 (5–200) | 21 (2–140) | 21 (12–38) | 46 (30–106) | 28 (17–80) | 25 (25) | 74 (16–131) | 41 | 20 (5–60) | 16 (2–116) |

| Diazoxide, max dose, mg/ kg/d | 11.3 (6.3–34.0) | 13.2 (3.8–23.8) | 6.4 (3.3–15.6) | 14.0 (5.1–21.0) | 14.5 (11.4–17.6) | 10.0 (6.7–12.0) | NA | 6.7 (4.0–12.0) | 6.2 (NA) | 12.5 (4.4–22.0) | 9.5 (2.3–20.1) |

| Diazoxide-responsive, % (n)d | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 92.9 (13) | 63.6 (7) | 0.0 (0) | 100.0 (6) | 50.0 (1) | 100.0 (3) | 100.0 (1) | 86.2 (25) | 100.0 (54) |

| Surgery, % (n) | 100.0 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 7.1 (1) | 36.4 (4) | 25.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 13.3 (4) | NA |

Abbreviations: HOM, homozygous; HET, heterozygous; CH, compound heterozygous; P/LP, pathogenic/Likely pathogenic.

Categorical variables represented as percentage (%) and number (n) of the patients. Continuous variables represented as median (range) values.

aBorn before 37 gestational weeks; bbirth weight SDS >2.0; cin neonates; dwhen used.

Persistent CHI

Genetic variants.

In total, 5 novel and 21 previously reported (4, 9, 10, 21–35) pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 65 patients with P-CHI from 55 families (Table 2) (15). None of the 58 unrelated patients with T-CHI carried a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants of the patients with congenital hyperinsulinism.

| Gene . | Transcript . | Allele . | Protein . | In silico analyses . | Carriers (n) . | Ref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC8 | NM_000352.4 | c.560T>A | p.(Val187Asp) | P | 24 | (9) |

| c.1576C>Ta | p.(Arg526Cys) | P | 1 | (4) | ||

| c.3280_3281dela | p.(Lys1094Glufs*19) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.3336dup | p.(Glu1113*) | P | 1 | (21) | ||

| c.3551C>T | p.(Ala1184Val) | P | 1 | (22) | ||

| c.3640C>T | p.(Arg1214Trp) | P | 1 | (23) | ||

| c.4307G>A | p.(Arg1436Gln) | P | 1 | (24, 25) | ||

| c.4406G>T | p.(Gly1469Val) | P | 1 | (26) | ||

| c.4369G>Ab | p.(Ala1457Thr) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4372C>A | p.(Gln1458Lys) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4411G>Ab | p.(Asp1471Asn) | P | 2 | (28, 29) | ||

| c.4451G>A | p.(Gly1484Glu) | P | 1 | (30) | ||

| c.4516G>A | p.(Glu1506Lys) | P | 14 | (10) | ||

| c.4547A>C | p.(Glu1516Ala) | LP | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4649T>Ab | p.(Val1550Asp) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4651C>G | p.(Leu1551Val) | P | 2 | (27) | ||

| KCNJ11 | NM_000525.3 | c.201G>Cc | p.(Lys67Asn) | P | 2 | (27) |

| c.539C>T | p.(Thr180Ile) | P | 2 | Novel | ||

| C>T c | -54 bases proximal of the translation initiation site | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| GLUD1 | NM_005271.4 | c.965G>A | p.(Arg322His) | P | 4 | (31) |

| c.1493C>T | p.(Ser498Leu) | P | 2 | (32) | ||

| GCK | NM_033508.1 | c.193A>G | p.(Thr65Ala) | P | 1 | Novel |

| c.638A>G | p.(Tyr213Cys) | P | 1 | (33) | ||

| SLC16A1 | NM_003051.3 | c.-391_-390ins25bp | p.? | P | 2 | (34) |

| c.-202G>A | p.? | P | 1 | (34) | ||

| HNF4A | NM_000457.4 | c.992G>A | p.(Arg331His) | P | 1 | (35) |

| Gene . | Transcript . | Allele . | Protein . | In silico analyses . | Carriers (n) . | Ref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC8 | NM_000352.4 | c.560T>A | p.(Val187Asp) | P | 24 | (9) |

| c.1576C>Ta | p.(Arg526Cys) | P | 1 | (4) | ||

| c.3280_3281dela | p.(Lys1094Glufs*19) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.3336dup | p.(Glu1113*) | P | 1 | (21) | ||

| c.3551C>T | p.(Ala1184Val) | P | 1 | (22) | ||

| c.3640C>T | p.(Arg1214Trp) | P | 1 | (23) | ||

| c.4307G>A | p.(Arg1436Gln) | P | 1 | (24, 25) | ||

| c.4406G>T | p.(Gly1469Val) | P | 1 | (26) | ||

| c.4369G>Ab | p.(Ala1457Thr) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4372C>A | p.(Gln1458Lys) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4411G>Ab | p.(Asp1471Asn) | P | 2 | (28, 29) | ||

| c.4451G>A | p.(Gly1484Glu) | P | 1 | (30) | ||

| c.4516G>A | p.(Glu1506Lys) | P | 14 | (10) | ||

| c.4547A>C | p.(Glu1516Ala) | LP | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4649T>Ab | p.(Val1550Asp) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4651C>G | p.(Leu1551Val) | P | 2 | (27) | ||

| KCNJ11 | NM_000525.3 | c.201G>Cc | p.(Lys67Asn) | P | 2 | (27) |

| c.539C>T | p.(Thr180Ile) | P | 2 | Novel | ||

| C>T c | -54 bases proximal of the translation initiation site | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| GLUD1 | NM_005271.4 | c.965G>A | p.(Arg322His) | P | 4 | (31) |

| c.1493C>T | p.(Ser498Leu) | P | 2 | (32) | ||

| GCK | NM_033508.1 | c.193A>G | p.(Thr65Ala) | P | 1 | Novel |

| c.638A>G | p.(Tyr213Cys) | P | 1 | (33) | ||

| SLC16A1 | NM_003051.3 | c.-391_-390ins25bp | p.? | P | 2 | (34) |

| c.-202G>A | p.? | P | 1 | (34) | ||

| HNF4A | NM_000457.4 | c.992G>A | p.(Arg331His) | P | 1 | (35) |

Abbreviations: P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic.

aThe variants are compound heterozygous.

bThe variant is compound heterozygous for the founder mutation ABCC8/c.560T>A, p.(Val187Asp).

cThe variants are compound heterozygous.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants of the patients with congenital hyperinsulinism.

| Gene . | Transcript . | Allele . | Protein . | In silico analyses . | Carriers (n) . | Ref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC8 | NM_000352.4 | c.560T>A | p.(Val187Asp) | P | 24 | (9) |

| c.1576C>Ta | p.(Arg526Cys) | P | 1 | (4) | ||

| c.3280_3281dela | p.(Lys1094Glufs*19) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.3336dup | p.(Glu1113*) | P | 1 | (21) | ||

| c.3551C>T | p.(Ala1184Val) | P | 1 | (22) | ||

| c.3640C>T | p.(Arg1214Trp) | P | 1 | (23) | ||

| c.4307G>A | p.(Arg1436Gln) | P | 1 | (24, 25) | ||

| c.4406G>T | p.(Gly1469Val) | P | 1 | (26) | ||

| c.4369G>Ab | p.(Ala1457Thr) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4372C>A | p.(Gln1458Lys) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4411G>Ab | p.(Asp1471Asn) | P | 2 | (28, 29) | ||

| c.4451G>A | p.(Gly1484Glu) | P | 1 | (30) | ||

| c.4516G>A | p.(Glu1506Lys) | P | 14 | (10) | ||

| c.4547A>C | p.(Glu1516Ala) | LP | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4649T>Ab | p.(Val1550Asp) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4651C>G | p.(Leu1551Val) | P | 2 | (27) | ||

| KCNJ11 | NM_000525.3 | c.201G>Cc | p.(Lys67Asn) | P | 2 | (27) |

| c.539C>T | p.(Thr180Ile) | P | 2 | Novel | ||

| C>T c | -54 bases proximal of the translation initiation site | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| GLUD1 | NM_005271.4 | c.965G>A | p.(Arg322His) | P | 4 | (31) |

| c.1493C>T | p.(Ser498Leu) | P | 2 | (32) | ||

| GCK | NM_033508.1 | c.193A>G | p.(Thr65Ala) | P | 1 | Novel |

| c.638A>G | p.(Tyr213Cys) | P | 1 | (33) | ||

| SLC16A1 | NM_003051.3 | c.-391_-390ins25bp | p.? | P | 2 | (34) |

| c.-202G>A | p.? | P | 1 | (34) | ||

| HNF4A | NM_000457.4 | c.992G>A | p.(Arg331His) | P | 1 | (35) |

| Gene . | Transcript . | Allele . | Protein . | In silico analyses . | Carriers (n) . | Ref. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC8 | NM_000352.4 | c.560T>A | p.(Val187Asp) | P | 24 | (9) |

| c.1576C>Ta | p.(Arg526Cys) | P | 1 | (4) | ||

| c.3280_3281dela | p.(Lys1094Glufs*19) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.3336dup | p.(Glu1113*) | P | 1 | (21) | ||

| c.3551C>T | p.(Ala1184Val) | P | 1 | (22) | ||

| c.3640C>T | p.(Arg1214Trp) | P | 1 | (23) | ||

| c.4307G>A | p.(Arg1436Gln) | P | 1 | (24, 25) | ||

| c.4406G>T | p.(Gly1469Val) | P | 1 | (26) | ||

| c.4369G>Ab | p.(Ala1457Thr) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4372C>A | p.(Gln1458Lys) | P | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4411G>Ab | p.(Asp1471Asn) | P | 2 | (28, 29) | ||

| c.4451G>A | p.(Gly1484Glu) | P | 1 | (30) | ||

| c.4516G>A | p.(Glu1506Lys) | P | 14 | (10) | ||

| c.4547A>C | p.(Glu1516Ala) | LP | 1 | Novel | ||

| c.4649T>Ab | p.(Val1550Asp) | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| c.4651C>G | p.(Leu1551Val) | P | 2 | (27) | ||

| KCNJ11 | NM_000525.3 | c.201G>Cc | p.(Lys67Asn) | P | 2 | (27) |

| c.539C>T | p.(Thr180Ile) | P | 2 | Novel | ||

| C>T c | -54 bases proximal of the translation initiation site | P | 1 | (27) | ||

| GLUD1 | NM_005271.4 | c.965G>A | p.(Arg322His) | P | 4 | (31) |

| c.1493C>T | p.(Ser498Leu) | P | 2 | (32) | ||

| GCK | NM_033508.1 | c.193A>G | p.(Thr65Ala) | P | 1 | Novel |

| c.638A>G | p.(Tyr213Cys) | P | 1 | (33) | ||

| SLC16A1 | NM_003051.3 | c.-391_-390ins25bp | p.? | P | 2 | (34) |

| c.-202G>A | p.? | P | 1 | (34) | ||

| HNF4A | NM_000457.4 | c.992G>A | p.(Arg331His) | P | 1 | (35) |

Abbreviations: P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic.

aThe variants are compound heterozygous.

bThe variant is compound heterozygous for the founder mutation ABCC8/c.560T>A, p.(Val187Asp).

cThe variants are compound heterozygous.

The distribution of pathogenic or likely pathogenic gene variants of patients with P-CHI is presented in Fig. 1. As a whole, these variants in 6 CHI-associated genes, ABCC8, KCNJ11, GLUD1, SLC16A1, GCK, and HNF4A, explained the genetic etiology in 68% (n = 65) of the patients. KATP variants were the most common causes of CHI (82%, n = 53).

The frequencies of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in all patients with P-CHI (A) and the distribution of these variants (B).

ABCC8 variants.

Altogether, 16 different ABCC8 variants were identified, including 3 novel variants, explaining 75% (n = 49) of the mutation positive cases (Table 2 and Fig. 1) (15). The previously characterized 2 Finnish founder mutations (ABCC8/p.Val187Asp (9) and ABCC8/p.Glu1506Lys (10)) explained 58% (n = 38) of the genetic etiology of P-CHI patients. The autosomal recessive ABCC8/p.Val187Asp (9) variant was found in 24 patients from 23 families, explaining the genetic etiology in 37% of the mutation positive patients. Five patients were homozygous and 4 compound heterozygous for ABCC8/p.Val187Asp. They tended to be born preterm (67%) and were large for gestational age (67%). All had neonatal onset within 2 days after the birth and all were diazoxide unresponsive. This subgroup and especially the patients with the homozygous variant tended to have the highest plasma insulin levels at diagnosis (Table 1) (15). Fifteen patients were heterozygous for ABCC8/p.Val187Asp. All these patients were diazoxide unresponsive. Sixty-seven percent had neonatal onset, but only 13% were born large for gestational age.

The autosomal dominant founder mutation ABCC8/p.Glu1506Lys (10) was detected in 14 patients from 6 families, explaining the genetic etiology in 22% of the cases. Of these, 93% had a neonatal onset, 50% were born large for gestational age, and 93% were diazoxide responsive (Table 1).

Three novel ABCC8 variants were identified (Table 2) (15). One patient carried a novel pathogenic frameshift variant ABCC8/p.Lys1094Glufs*19 and a pathogenic ABCC8/p.Arg526Cys variant. The patient was born large for gestational age, responded well to diazoxide, and had a milder phenotype than other patients with compound heterozygous variants. The other novel heterozygous variants were ABCC8/p.Glu1516Ala and ABCC8/p.Gln1458Lys (de novo). The carriers of these variants were large for gestational age, had neonatal onset, and were responsive to diazoxide. In the latter patient, 18F-fluorodihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography scan referred to a multifocal disease.

Ten patients were heterozygous and 1 compound heterozygous for the other ABCC8 variants than the previously mentioned founder mutations p.Val187Asp or p.Glu1506Lys, and 4 of these ABCC8 variants were novel (Table 2) (15). These patients tended to be large for gestational age (64%) and have neonatal onset (91%) (Table 1). None had severe symptoms at onset and 64% were diazoxide responsive. Six of the 11 patients had paternal inheritance referring to focal CHI. Focal lesion was confirmed in surgery in 4 of them and 2 others were successfully treated with diazoxide.

KCNJ11 variants.

Four patients from 3 families carried a pathogenic or likely pathogenic KCNJ11 variant (Table 2) (15). All had neonatal onset and 50% were born large for gestational age (Table 1). One of the patients was compound heterozygous for KCNJ11/p.Lys67Asn and a promoter variant (substitution C to T at –54 bases proximal of the translation initiation site) that has been previously predicted to lead to a novel start codon and reduced number of KATP channels (27). This patient had a severe phenotype requiring near-total pancreatectomy.

GLUD1 variants.

Two previously reported heterozygous GLUD1 variants were identified in 6 patients from 3 families (Table 2) (15). These associated with an onset after the neonatal period (>28 days after birth) (83%), severe symptoms at onset (50%), and diazoxide responsiveness (100%) (Table 1). Diazoxide was started for 2 children after a positive test result of the variant found in the parent. Plasma ammonium levels were elevated at diagnosis (range from 95 to 318 µmol/L).

GCK variants.

Two patients carried pathogenic GCK variants. One patient carried a novel pathogenic activating GCK/p.Thr65Ala variant (Table 2) (15). The patient had normal birth size and remained asymptomatic until the age of 8 years. This patient was treated with diazoxide but the treatment could be discontinued after normoglycemia was achieved with dietary treatment. An activating GCK/p.Tyr213Cys variant (de novo) in another patient caused an extremely severe and drug-resistant form of CHI, as previously reported (33).

HNF4A variants.

A previously reported likely pathogenic variant HNF4A/p.Arg331His, which has been associated with MODY (35), was found in 1 patient having a mild neonatal-onset CHI, which responded well to diazoxide treatment (Table 2) (15).

SLC16A1 variants.

Two previously reported heterozygous SLC16A1 variants, SLC16A1/p.Asp15Argfs*34 and a SLC16A1 promoter variant (25 bp insertion at the position c.-391_-390) were found in 3 patients (Table 2) (15). The phenotype associating to these variants has been previously described (36, 37). In our cohort, the other patient with the promoter variant did not have clear clinical signs of exercise-induced hyperinsulinism.

Transient CHI

None of the patients with T-CHI carried a disease-causing CHI variant. In this group, 45% were born preterm and only 14% were large for gestational age. The median birth weight was –1.2 standard deviation score and none had severe symptoms at onset (Table 1). The median plasma insulin levels at diagnosis tended to be lower than in the patients with P-CHI (16 vs 25 mU/L; ranges 2–116 and 2–531 mU/L). One or more risk factors for hyperinsulinism of a newborn (maternal gestational diabetes or the use of β blockers, small for gestational age, prematurity <37 gestational weeks, or perinatal stress) was identified in 66% (n = 38) of the patients with T-CHI. The corresponding proportion in the P-CHI group was 53% (n = 50).

Syndrome-related CHI

Three participants had a syndrome previously associated with hyperinsulinism (Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (38), Turner mosaicism (39)). No CHI-associated genetic variants were identified in these patients (15).

Mutation negative patients with persistent CHI

Altogether, 32% (n = 30) of the subjects with P-CHI did not have a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant (Fig. 1). Of these, 53% had neonatal onset of the disease. Eighty-six percent were diazoxide responsive. Two patients underwent pancreatectomy, and 2 had focal resection of pancreas. An 18F-fluorodihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography scan referred to a focal CHI in 2 patients but they were successfully treated with medication.

Discussion

We investigated the genetics of CHI and the genotype–phenotype relationships in a nationwide cohort consisting almost entirely of Finnish patients with P-CHI or T-CHI. CHI-associated pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 68% and 0% of the patients with P-CHI and T-CHI, respectively, including 5 novel variants.

Previous large studies have reported CHI-associated variants in 45% (from 2 to 8 genes sequenced) (3, 5) and 79% (9 genes sequenced, syndromic CHI excluded) (4). Other smaller studies have reported pathogenic variants in 38% to 66% of the patients (6–9 genes sequenced) (6, 7, 40, 41). Our results are in agreement with these reports. Furthermore, variants in the KATP channel genes explained 82% of the variants in our study, as has also been reported in previous studies (6, 7, 40, 41).

Homozygosity or compound heterozygosity for the recessive KATP channel gene variants were associated with the most severe phenotypes, whereas variants in other than KATP channel genes were associated with diazoxide responsivity, except for an inactivating GCK variant. The patients with a GLUD1 variant showed elevated ammonium levels. Of the 20 paternally inherited heterozygous KATP gene variants, 65% were associated with focal or multifocal forms of CHI which was successfully treated with partial resection (15). Three patients carried a pathogenic variant in SLC16A1 gene, and 2 of them presented classical exercise-induced hyperinsulinism, but the clinical signs of exercise-induced hyperinsulinism were lacking in 1 patient most likely due to his young age.

Interestingly, 7 patients with heterozygous missense KATP variants and 1 with compound heterozygous ABCC8 variant were treated with diazoxide. The heterozygous variants may be dominant, as previously demonstrated by functional analysis in all monoallelic diazoxide-responsive KATP variants of a large cohort (4). In addition, a similar compound heterozygous case has been previously demonstrated to be diazoxide responsive in functional analysis (42). Moreover, it is also possible that cell adaptation and gene regulatory factors may contribute to the severity of CHI in all these 8 patients (13, 42). Several patients in our study carried a heterozygous, paternally inherited ABCC8 variant and were diazoxide unresponsive, but did not have a focal CHI. This may be explained by another yet unidentified variant, unidentified focal disease, dominant variant (in others than patients with p.Val187Asp), or contributing epigenetic factors (43, 44). Our findings are in agreement with previous studies showing the heterogeneity of CHI (1, 4, 13, 42, 43).

To our knowledge, our study is the first to perform extensive genetic analyses of patients with T-CHI. These patients responded well to diazoxide and the treatment could be discontinued within the first 4 months, the maximal diazoxide dose tended to be lower than in most patients with P-CHI, and none of these patients carried a pathogenic variant. Our findings are in agreement with a recently provided algorithm suggesting that genetic testing is appropriate only for the patients who are diazoxide unresponsive or need a high diazoxide dose, and in patients who continue on medication (regardless of the dose) after 6 months (13).

Targeted next-generation sequencing of selected 104 genes associated with glucose metabolism (15) did not reveal any novel candidate genes for CHI in our study. Gene panels including previously known disease-causing genes are important in clinical diagnostics, but identification of new causative genes is only possible through exome or whole genome sequencing.

Our study has some limitations. First, we did not perform functional studies of the identified novel variants. However, we used a wide range of in silico methods to predict the pathogenicity of all detected variants. Second, we applied targeted next-generation sequencing, which does not detect larger deletions/insertions or variants in noncoding region. This may underestimate the number of patients with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants. Third, it is possible that some of the patients who were not identified with a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant may have actually had T-CHI, since exact classification criteria are missing to differentiate T-CHI and P-CHI. Although the national diagnosis registries are mandatory and reliable, it cannot be excluded that some patients especially with a milder phenotype in the 1970 and 1980s have been un- or misdiagnosed. Finally, 4 currently known CHI-associated genes were not included in our panel for the reason that these genes were mostly published after we had completed our genetic analysis. However, our gene panel was the largest compared to previous studies.

In conclusion, the results of our study demonstrated that KATP channel genes were the major identified cause of CHI, and that the genotype–phenotype associations were consistent in several specific CHI subgroups. Pathogenic CHI-associated variants were not identified in patients who were both responsive for drug treatment and able to discontinue medication within the first four months, and therefore our results support the notion that genetic testing should be primarily done on patients with inadequate response or prolonged need for medical therapy.

Abbreviations

- CHI

congenital hyperinsulinism

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- P-CHI

persistent CHI

- T-CHI

transient CHI

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was funded by the Academy of Finland (to M.L.), the Foundation for Pediatric Research (to J.M. and H.H., grant numbers 140025, 160041, and 170069), the Finnish Cultural Foundation, North Savo Regional Fund (to J.M.), VTR grant from the Kuopio University Hospital (to J.M.), the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation (to J.M.).

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: Restrictions apply to the availability of data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

References

Author notes

Equal contribution.