-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Emma O Billington, Lauren A Burt, Marianne S Rose, Erin M Davison, Sharon Gaudet, Michelle Kan, Steven K Boyd, David A Hanley, Safety of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 4, April 2020, Pages 1261–1273, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz212

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

More than 3% of adults report vitamin D intakes of 4000 IU/day or more, but the safety of this practice is unknown.

The objective of this work is to establish whether vitamin D doses up to 10 000 IU/day are safe and well tolerated.

The Calgary Vitamin D Study was a 3-year, double-blind, randomized controlled trial.

A single-center study was conducted at the University of Calgary, Canada.

Participants included healthy adults (n = 373) ages 55 to 70 years with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D 30 to 125 nmol/L.

Participants were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to vitamin D3 400, 4000, or 10 000 IU/day. Calcium supplementation was initiated if dietary calcium intake was less than 1200 mg/day.

In these prespecified secondary analyses, changes in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, calcium, creatinine, 24-hour urine calcium excretion, and incidence of adverse events were assessed. Between-group differences in adverse events were examined using incident rate differences and logistic regression.

Of 373 participants (400: 124, 4000: 125, 10 000: 124), 49% were male, mean (SD) age was 64 (4) years, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D 78.0 (19.5) nmol/L. Serum calcium, creatinine, and 24-hour urine calcium excretion did not differ between treatments. Mild hypercalcemia (2.56-2.64 mmol/L) occurred in 15 (4%) participants (400: 0%, 4000: 3%, 10 000: 9%, P = .002); all cases resolved on repeat testing. Hypercalciuria occurred in 87 (23%) participants (400: 17%, 4000: 22%, 10 000: 31%, P = .01). Clinical adverse events were experienced by 365 (97.9%) participants and were balanced across treatment arms.

The safety profile of vitamin D supplementation is similar for doses of 400, 4000, and 10 000 IU/day. Hypercalciuria was common and occurred more frequently with higher doses. Hypercalcemia occurred more frequently with higher doses but was rare, mild, and transient.

Despite a lack of convincing benefit to individuals who are not vitamin D deficient (1-3), enthusiasm for vitamin D supplementation is widespread. Estimates indicate that more than half of US adults take a vitamin D supplement (4), and more than 3% (> 7 million individuals) consume 4000 IU/day or more (5). The safety of this practice is unclear.

When taken at very high doses (ie, > 25 000 IU/day), vitamin D supplementation may precipitate hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nephrolithiasis, renal dysfunction, and soft-tissue calcification (6, 7). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D set the tolerable upper intake limit at 4000 IU/day (6), a dose likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects to almost all individuals in the general population. It has been suggested that the tolerable limit could be increased to 10 000 IU/day because hypercalcemia is rarely encountered at lower doses (6, 8-10), and most reports of other manifestations of vitamin D toxicity (ie, lethargy, confusion, vomiting, arrhythmia, nephrocalcinosis) are limited to doses exceeding 40 000 IU/day (9). Previously available data regarding the safety of doses of more than 4000 IU/day have been primarily limited to small, heterogeneous, short-term studies (11-13). However, a recent 1-year trial comparing supplementation with vitamin D 10 000 or 600 IU/day in 132 postmenopausal women also receiving calcium carbonate 1200 mg/day found that the 10 000 IU/day dose was associated with a 3.6-fold increased risk of developing hypercalciuria (14).

Our group conducted a 3-year, double-blind, randomized controlled trial to examine the skeletal effects and safety of vitamin D3 supplementation with 400, 4000, or 10 000 IU/day. Compared to 400 IU/day, no bone strength benefits and a small dose-dependent decrease in bone density was observed with doses of 4000 or 10 000 IU/day; episodes of mild hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria were also more frequent with these higher doses (15). Here, we report the complete prespecified safety outcomes from this study (16). We hypothesized that supplementation with up to 10 000 IU/day would be safe and well tolerated.

Methods

Trial design

The study design (16) and primary outcomes (volumetric bone density and strength) (15) have been described in detail elsewhere. Briefly, in this double-blind study, 373 healthy adults were recruited into either a pilot (n = 62) or main (n = 311) cohort and randomly assigned 1:1:1 to receive 400, 4000, or 10 000 IU oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) daily for 3 years. Primary outcomes and select safety outcomes have been published for the main cohort (15); as previously reported, the pilot cohort received the same study intervention as the main cohort but did not undergo primary outcome measurements. Therefore, the present study describes all prespecified and exploratory safety outcomes both for the pilot and main cohorts (n = 373). All decisions about which participants to include in these analyses were made prior to unblinding and data analysis; all 373 individuals who received the study intervention were included in safety analyses to reduce the likelihood of failing to detect uncommon but clinically important adverse events (AEs).

Study visits and data collection took place at a single center (McCaig Institute for Bone & Joint Health, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Canada). Prior to initiation, the trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01900860), with approval granted by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (ID: 24882) and a letter of no objection obtained from Health Canada. An independent data and safety monitoring board had access to unblinded data and completed interim safety analyses at regular intervals.

Participants

Healthy men and postmenopausal women between ages 55 and 70 years residing in or near Calgary, Canada, were recruited via letters and advertisements. Eligible participants had lumbar spine and total hip bone mineral density T scores greater than –2.5, assessed using dual–x-ray absorptiometry. Exclusion criteria consisted of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) less than 30 or greater than 125 nmol/L, serum calcium greater than 2.5 or less than 2.10 mmol/L, consumption of vitamin D supplements of more than 2000 IU/day within the previous 6 months, use of bone-active medication within the past 2 years, and disorders known to affect vitamin D metabolism. All participants provided written informed consent.

Intervention and procedures

Participants were randomly assigned to receive vitamin D3 400, 4000, or 10 000 IU/day for 3 years (16). These intervention doses were selected because the IOM has set the recommended daily intake at 600 IU/day for adults ages 51 to 70 years—which for most individuals can be achieved with a 400 IU supplement given that dietary vitamin D intake averages 200 IU/day—and the tolerable upper intake limit at 4000 IU/day (6), although it has been argued that up to 10 000 IU/day is safe (8–10). Vitamin D3 was provided by Ddrops Canada (Woodbridge) as a bottled liquid, with each bottle containing a metered dropper. Quality control procedures and administration technique have been previously described (16). All participants self-administered 5 drops of vitamin D3 liquid orally each day, regardless of treatment allocation. Concentration of vitamin D3 liquid varied according to treatment arm (400: 80 IU/drop, 4000: 800 IU/drop, 10 000: 2000 IU/drop). Participants and outcome assessors were blinded as to treatment allocation and serum 25OHD measurements throughout the study.

Participants were permitted to take up to 200 IU/day of vitamin D in addition to the study intervention (eg, a multivitamin). Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake were evaluated at screening using a food frequency questionnaire (17). If dietary calcium intake was less than the recommended 1200 mg/day (18), a daily supplement containing either 300 mg or 600 mg elemental calcium was provided to approximate a total daily intake of 1200 mg.

Data collection

Study visits took place at baseline and at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months. At each visit, medication use, multivitamin, and additional vitamin D supplement intake (up to 200 IU/day) were monitored, and a fasting morning blood sample was collected and analyzed for the following parameters: serum 25OHD, calcium, albumin, parathyroid hormone (PTH), creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). All clinical chemistry measurements were performed at a centralized laboratory (Calgary Laboratory Services [CLS]). Assay platforms and procedures have been described previously (16). Fasting serum 25OHD was measured by a DiaSorin Liaison XL system; CLS participates in the Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation (19). Participants underwent 24-hour urine collections for calcium and creatinine at baseline and months 12, 24, and 36. A second void urine sample was collected and calcium:creatinine ratio determined at months 6, 18, and 30, and at other time points in cases for which the participant could not provide a 24-hour urine sample or required follow-up testing after hypercalciuria was detected.

Hypercalcemia was defined as total serum calcium level exceeding normal range (> 2.55 mmol/L), liver enzyme elevation as AST or ALT greater than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), and renal dysfunction as serum creatinine less than 133 μmol/L (20). A 24-hour urine calcium excretion exceeding 7.5 mmol/day was used as the cutoff for hypercalciuria for participants of less than 75 kg body weight; a weight-based cutoff less than 0.1 mmol/kg/day was used for those heavier than 75 kg (21). The presence of any of these biochemical abnormalities prompted review of testing protocols (ie, fasting for blood draw, appropriate 24-hour urine collection procedure) with the participant, followed by repeat testing. In the case of detected hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria, if there was no evidence of violation of the testing protocol, the participant was advised to reduce supplemental calcium intake (or dietary calcium intake if not taking a supplement) prior to repeat testing. When hypercalcemia occurred, an electrocardiogram was performed if the participant endorsed symptoms of hypercalcemia. Participants were asked to discontinue the study intervention if repeat testing demonstrated persistent hypercalcemia, liver enzyme elevations, or renal dysfunction. The second void urine calcium:creatinine ratio served as a safety flag for the identification of significant hypercalciuria. A ratio of 1.0 mmol/mmol or more at month 6, 18, or 30 prompted review by a study physician of the participant’s next 24-hour urine calcium excretion. A ratio of 1.0 mmol/mmol or more conducted at follow-up of an elevated 24-hour urine calcium excretion resulted in discontinuation of the study treatment.

At the baseline visit, fall and fracture status were ascertained via questionnaire. Participants were asked whether they had sustained any falls within the past year, and whether they had sustained any fractures since age 50 years. At each subsequent study visit, participants were asked to report any new or ongoing medical issues and hospitalizations. All reported AEs were reviewed and classified by organ system and by seriousness and severity; classification was performed by a study physician (E.O.B. or D.A.H.). The following clinical AEs of special interest were defined a priori: serious AEs, skin, and nonskin cancer diagnoses, low-trauma fractures, falls, and nephrolithiasis. Serious AEs were defined as events that were fatal or life-threatening, or that resulted in hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospital stay, persistent or significant incapacity, or disability (22). In individuals who reported a fracture, a description of the mechanism of fracture was obtained. Low-trauma fractures were defined as clinical fractures of any bone (excluding fingers and toes) that occurred as the result of a fall from standing height or less. Morphometric vertebral fractures were not assessed. At each study visit, participants were asked whether they had sustained any falls since the last visit. Falls resulting from sports participation were not included in analyses. Serious AEs, cancer diagnoses, low-trauma fractures, and nephrolithiasis were adjudicated by a study physician (D.A.H. or E.O.B.) via review of the participant’s medical chart and relevant imaging. Decisions to discontinue the study intervention on the basis of clinical AEs were made by the study physicians, in conjunction with the participant and the clinical care team.

Outcomes

Prespecified safety outcomes were changes in biochemical parameters (serum 25OHD, serum calcium, serum creatinine, 24-hour urine calcium excretion) and occurrence of biochemical and clinical AEs (hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, liver enzyme elevation, renal dysfunction, decline in eGFR of more than 10 mL/min/1.73 m2, deaths, serious AEs, AEs leading to study withdrawal, nephrolithiasis, falls, low-trauma fractures, skin and nonskin cancer diagnoses). The incidences of infections and, specifically, upper respiratory tract infections were exploratory outcomes.

Statistical methods

Biochemical safety parameters were evaluated using descriptive statistics for each treatment outcome at each time point. The distributions of the continuous variables were described using boxplots. For each biochemical and clinical AE, we tabulated the total number of occurrences in each treatment arm and the proportion of participants in each treatment group who experienced the AE. For all prespecified AEs with an overall prevalence less than or equal to 4% and less than or equal to 96%, we examined formally for between-group differences for trend in proportions using logistic regression (23). Incidence rate differences with 95% CIs were calculated using the 400 IU/day group as the referent. Student t tests were used to evaluate differences in mean 25OHD and PTH levels during states of hypercalcemia and normocalcemia, and during states of hypercalciuria and normocalciuria. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant and were not adjusted. Analyses were undertaken with R version 3.4 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

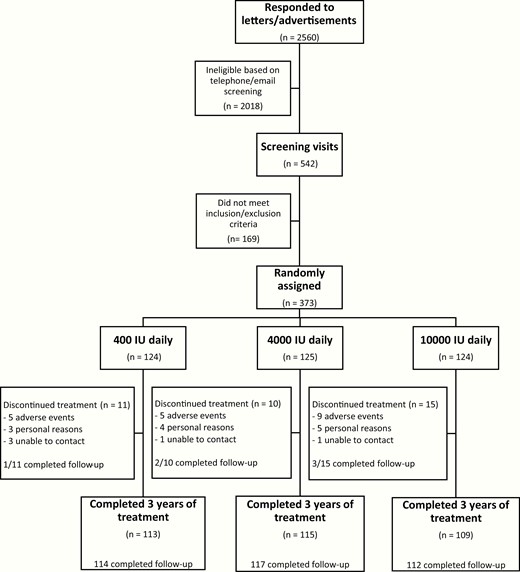

We enrolled 373 participants (49.1% male) with mean (SD) serum 25OHD of 78.0 (19.5) nmol/L between August 2013 and November 2014. Data collection was completed as planned in December 2017. Flow of participants through the study is outlined in Fig. 1. The 3 treatment groups were comparable with respect to baseline characteristics (Table 1). All randomly assigned participants received at least 1 dose of the study treatment and were included in safety analyses. In total, 36 (9.7%) participants discontinued the study intervention prematurely (400: 8.9%, 4000: 8.0%, 10 000: 12.1%). Premature treatment discontinuation resulted from an AE in 20 (5.4%) participants (400: 4.0%, 4000: 4.8%, 10 000: 7.3%). All supplementary tables and figures are available in a digital research repository, including a table summarizing the AEs resulting in treatment discontinuation (24). Fewer than 1% of vitamin D doses were missed by active study participants, with adherence rates of 99.6%, 99.7%, and 99.1% for the 400, 4000, and 10 000 IU/day groups, respectively. A total of 263 (70.5%) participants (400: 75.0%, 4000: 63.2%, 10 000: 73.4%) were started on calcium supplementation at the time of random assignment to achieve a total daily calcium intake of approximately 1200 mg. During the study, 86 (32.7%) calcium supplement takers (400: 24.7%, 4000: 34.2%, 10 000: 39.6%) discontinued their supplemental calcium. Of the 110 participants who did not start a calcium supplement at baseline, 20 (18.2%) initiated calcium supplementation during the study.

| Variable . | 10 000 IU . | 4000 IU . | 400 IU . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 124 | 125 | 124 |

| Male sex (%) | 61 (49.2%) | 58 (46.4%) | 64 (51.6%) |

| Age, y | 62.0 (4.1) | 62.7 (4.3) | 62.0 (4.2) |

| Time since menopause (y) | 12.5 (5.6) | 11.4 (6.7) | 11.9 (5.8) |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) | 117 (94.4%) | 118 (94.4%) | 115 (92.7%) |

| Dietary calcium intake (mg/day) | 639 (344) | 624 (279) | 600 (303) |

| Dietary vitamin D intake (IU/day) | 188 (120) | 178 (92) | 166 (88) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 (4.4) | 27.8 (5.0) | 27.7 (4.4) |

| Body fat (%) | 33.0 (8.4%) | 34.3 (8.9%) | 34.1 (8.9%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126 (16) | 130 (17) | 128 (15) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80 (10) | 80 (9) | 81 (8) |

| History of skin cancer (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 9 (7.2%) | 13 (10.5%) |

| History of nonskin cancer (%)a | 12 (9.7%) | 9 (7.2%) | 7 (5.6%) |

| History of cardiovascular condition (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 14 (11.2%) | 24 (19.4%) |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Asthma (%) | 11 (8.9%) | 10 (8.0%) | 6 (4.8%) |

| Current smoker (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Fall(s) within past year (%) | 19 (15.3%) | 22 (17.6%) | 27 (21.8%) |

| Fracture(s) since age 50 y (%) | 23 (18.5%) | 16 (12.8%) | 23 (18.5%) |

| Lumbar spine T-score | –0.1 (1.4) | 0.1 (1.4) | 0.0 (1.4) |

| Total hip T-score | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.0 (1.1) |

| Serum 25OHD (nmol/L) | 78 (18) | 80 (20) | 76 (21) |

| Serum PTH (ng/L) | 22.6 (7.4) | 21.7 (6.4) | 22.1 (7.4) |

| Serum calcium (nmol/L) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) |

| Serum phosphate (nmol/L) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 80 (14) | 79 (14) | 80 (14) |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min) | 80 (11) | 80 (12) | 81 (11) |

| 24-hour urine calcium (mmol/day) | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 70 (17) | 67 (15) | 70 (20) |

| Plasma CTX (ng/L) | 345 (123) | 343 (135) | 334 (126) |

| Fasting blood glucose(mmol/L) | 5.7 (0.7) | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.5) |

| Hemoglobin A1C (%) | 5.2 (1.5%) | 5.0 (0.8%) | 5.2 (1.2%) |

| Variable . | 10 000 IU . | 4000 IU . | 400 IU . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 124 | 125 | 124 |

| Male sex (%) | 61 (49.2%) | 58 (46.4%) | 64 (51.6%) |

| Age, y | 62.0 (4.1) | 62.7 (4.3) | 62.0 (4.2) |

| Time since menopause (y) | 12.5 (5.6) | 11.4 (6.7) | 11.9 (5.8) |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) | 117 (94.4%) | 118 (94.4%) | 115 (92.7%) |

| Dietary calcium intake (mg/day) | 639 (344) | 624 (279) | 600 (303) |

| Dietary vitamin D intake (IU/day) | 188 (120) | 178 (92) | 166 (88) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 (4.4) | 27.8 (5.0) | 27.7 (4.4) |

| Body fat (%) | 33.0 (8.4%) | 34.3 (8.9%) | 34.1 (8.9%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126 (16) | 130 (17) | 128 (15) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80 (10) | 80 (9) | 81 (8) |

| History of skin cancer (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 9 (7.2%) | 13 (10.5%) |

| History of nonskin cancer (%)a | 12 (9.7%) | 9 (7.2%) | 7 (5.6%) |

| History of cardiovascular condition (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 14 (11.2%) | 24 (19.4%) |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Asthma (%) | 11 (8.9%) | 10 (8.0%) | 6 (4.8%) |

| Current smoker (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Fall(s) within past year (%) | 19 (15.3%) | 22 (17.6%) | 27 (21.8%) |

| Fracture(s) since age 50 y (%) | 23 (18.5%) | 16 (12.8%) | 23 (18.5%) |

| Lumbar spine T-score | –0.1 (1.4) | 0.1 (1.4) | 0.0 (1.4) |

| Total hip T-score | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.0 (1.1) |

| Serum 25OHD (nmol/L) | 78 (18) | 80 (20) | 76 (21) |

| Serum PTH (ng/L) | 22.6 (7.4) | 21.7 (6.4) | 22.1 (7.4) |

| Serum calcium (nmol/L) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) |

| Serum phosphate (nmol/L) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 80 (14) | 79 (14) | 80 (14) |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min) | 80 (11) | 80 (12) | 81 (11) |

| 24-hour urine calcium (mmol/day) | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 70 (17) | 67 (15) | 70 (20) |

| Plasma CTX (ng/L) | 345 (123) | 343 (135) | 334 (126) |

| Fasting blood glucose(mmol/L) | 5.7 (0.7) | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.5) |

| Hemoglobin A1C (%) | 5.2 (1.5%) | 5.0 (0.8%) | 5.2 (1.2%) |

Values are presented as mean (SD) or n (n/N %)

Abbreviations: 25OHD = 25-hydroxyvitamin D; BMI, body mass index; CTX, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen; P GFR, glomerular filtration rate; TH, parathyroid hormone.

aIncludes melanoma.

| Variable . | 10 000 IU . | 4000 IU . | 400 IU . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 124 | 125 | 124 |

| Male sex (%) | 61 (49.2%) | 58 (46.4%) | 64 (51.6%) |

| Age, y | 62.0 (4.1) | 62.7 (4.3) | 62.0 (4.2) |

| Time since menopause (y) | 12.5 (5.6) | 11.4 (6.7) | 11.9 (5.8) |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) | 117 (94.4%) | 118 (94.4%) | 115 (92.7%) |

| Dietary calcium intake (mg/day) | 639 (344) | 624 (279) | 600 (303) |

| Dietary vitamin D intake (IU/day) | 188 (120) | 178 (92) | 166 (88) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 (4.4) | 27.8 (5.0) | 27.7 (4.4) |

| Body fat (%) | 33.0 (8.4%) | 34.3 (8.9%) | 34.1 (8.9%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126 (16) | 130 (17) | 128 (15) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80 (10) | 80 (9) | 81 (8) |

| History of skin cancer (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 9 (7.2%) | 13 (10.5%) |

| History of nonskin cancer (%)a | 12 (9.7%) | 9 (7.2%) | 7 (5.6%) |

| History of cardiovascular condition (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 14 (11.2%) | 24 (19.4%) |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Asthma (%) | 11 (8.9%) | 10 (8.0%) | 6 (4.8%) |

| Current smoker (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Fall(s) within past year (%) | 19 (15.3%) | 22 (17.6%) | 27 (21.8%) |

| Fracture(s) since age 50 y (%) | 23 (18.5%) | 16 (12.8%) | 23 (18.5%) |

| Lumbar spine T-score | –0.1 (1.4) | 0.1 (1.4) | 0.0 (1.4) |

| Total hip T-score | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.0 (1.1) |

| Serum 25OHD (nmol/L) | 78 (18) | 80 (20) | 76 (21) |

| Serum PTH (ng/L) | 22.6 (7.4) | 21.7 (6.4) | 22.1 (7.4) |

| Serum calcium (nmol/L) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) |

| Serum phosphate (nmol/L) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 80 (14) | 79 (14) | 80 (14) |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min) | 80 (11) | 80 (12) | 81 (11) |

| 24-hour urine calcium (mmol/day) | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 70 (17) | 67 (15) | 70 (20) |

| Plasma CTX (ng/L) | 345 (123) | 343 (135) | 334 (126) |

| Fasting blood glucose(mmol/L) | 5.7 (0.7) | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.5) |

| Hemoglobin A1C (%) | 5.2 (1.5%) | 5.0 (0.8%) | 5.2 (1.2%) |

| Variable . | 10 000 IU . | 4000 IU . | 400 IU . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 124 | 125 | 124 |

| Male sex (%) | 61 (49.2%) | 58 (46.4%) | 64 (51.6%) |

| Age, y | 62.0 (4.1) | 62.7 (4.3) | 62.0 (4.2) |

| Time since menopause (y) | 12.5 (5.6) | 11.4 (6.7) | 11.9 (5.8) |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) | 117 (94.4%) | 118 (94.4%) | 115 (92.7%) |

| Dietary calcium intake (mg/day) | 639 (344) | 624 (279) | 600 (303) |

| Dietary vitamin D intake (IU/day) | 188 (120) | 178 (92) | 166 (88) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 (4.4) | 27.8 (5.0) | 27.7 (4.4) |

| Body fat (%) | 33.0 (8.4%) | 34.3 (8.9%) | 34.1 (8.9%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126 (16) | 130 (17) | 128 (15) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80 (10) | 80 (9) | 81 (8) |

| History of skin cancer (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 9 (7.2%) | 13 (10.5%) |

| History of nonskin cancer (%)a | 12 (9.7%) | 9 (7.2%) | 7 (5.6%) |

| History of cardiovascular condition (%) | 16 (12.9%) | 14 (11.2%) | 24 (19.4%) |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Asthma (%) | 11 (8.9%) | 10 (8.0%) | 6 (4.8%) |

| Current smoker (%) | 5 (4.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Fall(s) within past year (%) | 19 (15.3%) | 22 (17.6%) | 27 (21.8%) |

| Fracture(s) since age 50 y (%) | 23 (18.5%) | 16 (12.8%) | 23 (18.5%) |

| Lumbar spine T-score | –0.1 (1.4) | 0.1 (1.4) | 0.0 (1.4) |

| Total hip T-score | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.0 (1.1) |

| Serum 25OHD (nmol/L) | 78 (18) | 80 (20) | 76 (21) |

| Serum PTH (ng/L) | 22.6 (7.4) | 21.7 (6.4) | 22.1 (7.4) |

| Serum calcium (nmol/L) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) |

| Serum phosphate (nmol/L) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 80 (14) | 79 (14) | 80 (14) |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min) | 80 (11) | 80 (12) | 81 (11) |

| 24-hour urine calcium (mmol/day) | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 70 (17) | 67 (15) | 70 (20) |

| Plasma CTX (ng/L) | 345 (123) | 343 (135) | 334 (126) |

| Fasting blood glucose(mmol/L) | 5.7 (0.7) | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.5) |

| Hemoglobin A1C (%) | 5.2 (1.5%) | 5.0 (0.8%) | 5.2 (1.2%) |

Values are presented as mean (SD) or n (n/N %)

Abbreviations: 25OHD = 25-hydroxyvitamin D; BMI, body mass index; CTX, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen; P GFR, glomerular filtration rate; TH, parathyroid hormone.

aIncludes melanoma.

Changes in biochemical parameters

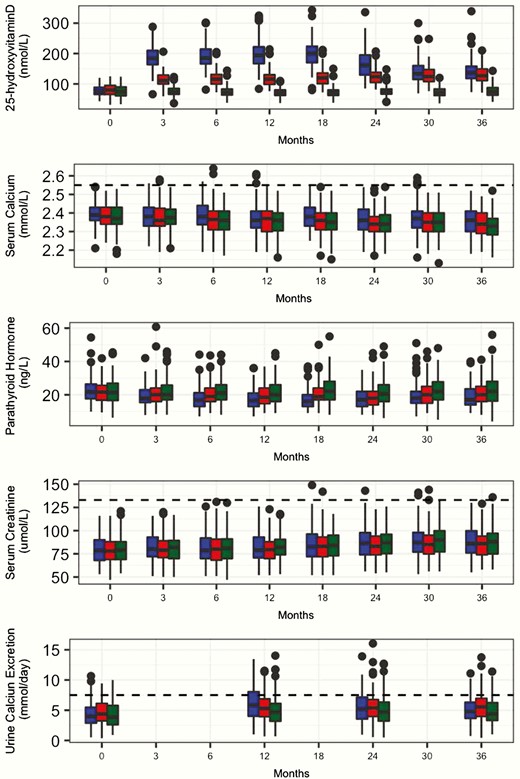

Fig. 2 depicts serum 25OHD, calcium, PTH, and creatinine concentrations and 24-hour urinary calcium excretion throughout the study.

Box plots of 3-year changes in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, serum calcium, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), serum creatinine, and 24-hour urine calcium in healthy adults taking vitamin D 10 000 IU (blue), 4000 IU (red), or 400 IU/day (green). Boxes show medians and interquartile ranges. The whiskers show the adjacent values, which indicate where approximately 99% of the values of the data lie. Horizontal dashed lines represent the upper limit of the normal range for serum calcium (second panel), 133 µmol/L for serum creatinine (third panel), and 24-hour urine calcium excretion of 7.5 mmol/day (fourth panel).

At month 3, mean (SD) 25OHD levels were 76 (17), 114 (22), and 187 (38) nmol/L in the 400, 4000, and 10 000 groups, respectively. The highest individual 25OHD level (343 nmol/L) occurred at month 18 in a participant taking 10 000 IU/day, and no participants discontinued the study treatment based on elevated 25OHD. In the 10 000 group, peak mean (SD) 25OHD concentration achieved in the study was 198 (42) nmol/L, occurring at month 18. As previously reported (15), following data collection and unblinding, it was determined that 2 lots of the investigational product provided to participants in the 10 000 IU/day group, beginning between months 18 and 24, and continued up until month 36, had suffered from varying degrees of premature degradation; as a result, the 10 000 group actually received doses estimated between 2000 and 10 000 IU/day throughout this timeframe. Despite this problem, the 10 000 group mean 25OHD remained at or above the levels achieved by the 4000 IU group (Fig. 2).

The 3 treatment groups did not differ throughout the study in terms of serum calcium or creatinine concentrations, or 24-hour urinary calcium excretion (Fig. 2). As previously reported for a subset of the study population (15) and shown in Fig. 2, PTH levels decreased between baseline and month 18, being lowest in the 10 000 IU group.

Biochemical adverse events

Table 2 demonstrates the proportion of participants in each group with biochemical AEs. Three biochemical AEs had appropriate overall prevalence for formal between-group statistical testing; of these, 2 (hypercalcemia [P = .002] and hypercalciuria [P = .01]) were significantly different between groups and exhibited a dose-response effect, whereas 1 (decline in eGFR by more than 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 throughout the study [P = .32]) did not differ between treatment arms. Prespecified biochemical AEs that were not formally tested owing to very low overall prevalence were creatinine greater than 133 µmol/L (0.5%), and ALT or AST greater than 1.5 times the ULN (1.9%).

Summary of relevant biochemical and clinical adverse events in healthy adults taking vitamin D 10 000, 4000, or 400 IU daily for 3 years

| . | 10 000 IU (N = 124) . | . | 4000 IU (N = 125) . | . | 400 IU (N = 124) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . |

| Biochemical AEs | ||||||

| Hypercalcemia | 12 | 11 (9%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Hypercalciuria | 56 | 38 (31%) | 40 | 28 (22%) | 27 | 21 (17%) |

| Creatinine > 133 µmol/L | 4 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) |

| eGFR decline of > 10 mL/min | – | 53 (43%) | - | 40 (32%) | – | 47 (38%) |

| AST or ALT > 1.5 × ULNa | 3 | 3 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 8 | 5 (4%) |

| Clinical AEsb | ||||||

| All clinical AEs | 824 | 122 (98%) | 920 | 122 (98%) | 836 | 121 (98%) |

| Neurologic | 24 | 19 (15%) | 35 | 26 (21%) | 33 | 21 (17%) |

| Ophthalmologic | 22 | 17 (14%) | 33 | 21 (17%) | 34 | 22 (18%) |

| Otolaryngologic | 206 | 87 (70%) | 255 | 98 (78%) | 220 | 93 (75%) |

| Cardiovascular | 44 | 31 (25%) | 39 | 29 (23%) | 46 | 35 (28%) |

| Pulmonary | 43 | 29 (23%) | 54 | 34 (27%) | 55 | 39 (31%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 65 | 43 (35%) | 82 | 51 (41%) | 58 | 43 (35%) |

| Genitourinary | 55 | 30 (24%) | 37 | 24 (19%) | 37 | 25 (20%) |

| Endocrine | 12 | 11 (9%) | 8 | 7 (6%) | 6 | 6 (5%) |

| Hematologic | 12 | 12 (10%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 1 | 1 (1%) |

| Dermatologic | 53 | 36 (29%) | 65 | 49 (39%) | 59 | 37 (30%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 215 | 96 (77%) | 257 | 96 (77%) | 216 | 86 (69%) |

| Psychiatric | 21 | 21 (17%) | 12 | 11 (9%) | 24 | 23 (19%) |

| Otherc | 52 | 35 (28%) | 39 | 30 (24%) | 47 | 37 (30%) |

| Serious AEs | 21 | 19 (15%) | 16 | 12 (10%) | 22 | 18 (15%) |

| AEs of special interest | ||||||

| Falls | 10 | 8 (6%) | 13 | 12 (10%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Low-trauma fractures | 8 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Nephrolithiasis | 2 | 1 (1%) | 1 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Nonskin cancerd | 6 | 6 (5%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 2 | 2 (2%) |

| Skin cancer | 7 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 9 | 8 (7%) |

| Infections | 287 | 101 (81%) | 297 | 100 (80%) | 277 | 106 (86%) |

| URTIs | 166 | 80 (65%) | 204 | 89 (71%) | 194 | 89 (72%) |

| . | 10 000 IU (N = 124) . | . | 4000 IU (N = 125) . | . | 400 IU (N = 124) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . |

| Biochemical AEs | ||||||

| Hypercalcemia | 12 | 11 (9%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Hypercalciuria | 56 | 38 (31%) | 40 | 28 (22%) | 27 | 21 (17%) |

| Creatinine > 133 µmol/L | 4 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) |

| eGFR decline of > 10 mL/min | – | 53 (43%) | - | 40 (32%) | – | 47 (38%) |

| AST or ALT > 1.5 × ULNa | 3 | 3 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 8 | 5 (4%) |

| Clinical AEsb | ||||||

| All clinical AEs | 824 | 122 (98%) | 920 | 122 (98%) | 836 | 121 (98%) |

| Neurologic | 24 | 19 (15%) | 35 | 26 (21%) | 33 | 21 (17%) |

| Ophthalmologic | 22 | 17 (14%) | 33 | 21 (17%) | 34 | 22 (18%) |

| Otolaryngologic | 206 | 87 (70%) | 255 | 98 (78%) | 220 | 93 (75%) |

| Cardiovascular | 44 | 31 (25%) | 39 | 29 (23%) | 46 | 35 (28%) |

| Pulmonary | 43 | 29 (23%) | 54 | 34 (27%) | 55 | 39 (31%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 65 | 43 (35%) | 82 | 51 (41%) | 58 | 43 (35%) |

| Genitourinary | 55 | 30 (24%) | 37 | 24 (19%) | 37 | 25 (20%) |

| Endocrine | 12 | 11 (9%) | 8 | 7 (6%) | 6 | 6 (5%) |

| Hematologic | 12 | 12 (10%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 1 | 1 (1%) |

| Dermatologic | 53 | 36 (29%) | 65 | 49 (39%) | 59 | 37 (30%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 215 | 96 (77%) | 257 | 96 (77%) | 216 | 86 (69%) |

| Psychiatric | 21 | 21 (17%) | 12 | 11 (9%) | 24 | 23 (19%) |

| Otherc | 52 | 35 (28%) | 39 | 30 (24%) | 47 | 37 (30%) |

| Serious AEs | 21 | 19 (15%) | 16 | 12 (10%) | 22 | 18 (15%) |

| AEs of special interest | ||||||

| Falls | 10 | 8 (6%) | 13 | 12 (10%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Low-trauma fractures | 8 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Nephrolithiasis | 2 | 1 (1%) | 1 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Nonskin cancerd | 6 | 6 (5%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 2 | 2 (2%) |

| Skin cancer | 7 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 9 | 8 (7%) |

| Infections | 287 | 101 (81%) | 297 | 100 (80%) | 277 | 106 (86%) |

| URTIs | 166 | 80 (65%) | 204 | 89 (71%) | 194 | 89 (72%) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ULN, upper limit of normal; URTIs, upper respiratory tract infections.

aAST ULN = 32 IU/L for women and 40 IU/L for men, ALT ULN = 40 IU/L for women and 60 IU/L for men.

bAEs and serious AEs defined using the standard International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice definition.

cAEs that do not localize to a single organ system (eg, diffuse infectious symptoms, generalized allergic reactions, electrolyte abnormalities, fatigue, insomnia, weight changes).

dIncludes melanoma.

Summary of relevant biochemical and clinical adverse events in healthy adults taking vitamin D 10 000, 4000, or 400 IU daily for 3 years

| . | 10 000 IU (N = 124) . | . | 4000 IU (N = 125) . | . | 400 IU (N = 124) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . |

| Biochemical AEs | ||||||

| Hypercalcemia | 12 | 11 (9%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Hypercalciuria | 56 | 38 (31%) | 40 | 28 (22%) | 27 | 21 (17%) |

| Creatinine > 133 µmol/L | 4 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) |

| eGFR decline of > 10 mL/min | – | 53 (43%) | - | 40 (32%) | – | 47 (38%) |

| AST or ALT > 1.5 × ULNa | 3 | 3 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 8 | 5 (4%) |

| Clinical AEsb | ||||||

| All clinical AEs | 824 | 122 (98%) | 920 | 122 (98%) | 836 | 121 (98%) |

| Neurologic | 24 | 19 (15%) | 35 | 26 (21%) | 33 | 21 (17%) |

| Ophthalmologic | 22 | 17 (14%) | 33 | 21 (17%) | 34 | 22 (18%) |

| Otolaryngologic | 206 | 87 (70%) | 255 | 98 (78%) | 220 | 93 (75%) |

| Cardiovascular | 44 | 31 (25%) | 39 | 29 (23%) | 46 | 35 (28%) |

| Pulmonary | 43 | 29 (23%) | 54 | 34 (27%) | 55 | 39 (31%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 65 | 43 (35%) | 82 | 51 (41%) | 58 | 43 (35%) |

| Genitourinary | 55 | 30 (24%) | 37 | 24 (19%) | 37 | 25 (20%) |

| Endocrine | 12 | 11 (9%) | 8 | 7 (6%) | 6 | 6 (5%) |

| Hematologic | 12 | 12 (10%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 1 | 1 (1%) |

| Dermatologic | 53 | 36 (29%) | 65 | 49 (39%) | 59 | 37 (30%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 215 | 96 (77%) | 257 | 96 (77%) | 216 | 86 (69%) |

| Psychiatric | 21 | 21 (17%) | 12 | 11 (9%) | 24 | 23 (19%) |

| Otherc | 52 | 35 (28%) | 39 | 30 (24%) | 47 | 37 (30%) |

| Serious AEs | 21 | 19 (15%) | 16 | 12 (10%) | 22 | 18 (15%) |

| AEs of special interest | ||||||

| Falls | 10 | 8 (6%) | 13 | 12 (10%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Low-trauma fractures | 8 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Nephrolithiasis | 2 | 1 (1%) | 1 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Nonskin cancerd | 6 | 6 (5%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 2 | 2 (2%) |

| Skin cancer | 7 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 9 | 8 (7%) |

| Infections | 287 | 101 (81%) | 297 | 100 (80%) | 277 | 106 (86%) |

| URTIs | 166 | 80 (65%) | 204 | 89 (71%) | 194 | 89 (72%) |

| . | 10 000 IU (N = 124) . | . | 4000 IU (N = 125) . | . | 400 IU (N = 124) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . | Total Events, n . | Participants With Events, n (%) . |

| Biochemical AEs | ||||||

| Hypercalcemia | 12 | 11 (9%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Hypercalciuria | 56 | 38 (31%) | 40 | 28 (22%) | 27 | 21 (17%) |

| Creatinine > 133 µmol/L | 4 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 2 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) |

| eGFR decline of > 10 mL/min | – | 53 (43%) | - | 40 (32%) | – | 47 (38%) |

| AST or ALT > 1.5 × ULNa | 3 | 3 (2%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 8 | 5 (4%) |

| Clinical AEsb | ||||||

| All clinical AEs | 824 | 122 (98%) | 920 | 122 (98%) | 836 | 121 (98%) |

| Neurologic | 24 | 19 (15%) | 35 | 26 (21%) | 33 | 21 (17%) |

| Ophthalmologic | 22 | 17 (14%) | 33 | 21 (17%) | 34 | 22 (18%) |

| Otolaryngologic | 206 | 87 (70%) | 255 | 98 (78%) | 220 | 93 (75%) |

| Cardiovascular | 44 | 31 (25%) | 39 | 29 (23%) | 46 | 35 (28%) |

| Pulmonary | 43 | 29 (23%) | 54 | 34 (27%) | 55 | 39 (31%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 65 | 43 (35%) | 82 | 51 (41%) | 58 | 43 (35%) |

| Genitourinary | 55 | 30 (24%) | 37 | 24 (19%) | 37 | 25 (20%) |

| Endocrine | 12 | 11 (9%) | 8 | 7 (6%) | 6 | 6 (5%) |

| Hematologic | 12 | 12 (10%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 1 | 1 (1%) |

| Dermatologic | 53 | 36 (29%) | 65 | 49 (39%) | 59 | 37 (30%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 215 | 96 (77%) | 257 | 96 (77%) | 216 | 86 (69%) |

| Psychiatric | 21 | 21 (17%) | 12 | 11 (9%) | 24 | 23 (19%) |

| Otherc | 52 | 35 (28%) | 39 | 30 (24%) | 47 | 37 (30%) |

| Serious AEs | 21 | 19 (15%) | 16 | 12 (10%) | 22 | 18 (15%) |

| AEs of special interest | ||||||

| Falls | 10 | 8 (6%) | 13 | 12 (10%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Low-trauma fractures | 8 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 5 | 5 (4%) |

| Nephrolithiasis | 2 | 1 (1%) | 1 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 (0%) |

| Nonskin cancerd | 6 | 6 (5%) | 4 | 4 (3%) | 2 | 2 (2%) |

| Skin cancer | 7 | 7 (6%) | 3 | 3 (2%) | 9 | 8 (7%) |

| Infections | 287 | 101 (81%) | 297 | 100 (80%) | 277 | 106 (86%) |

| URTIs | 166 | 80 (65%) | 204 | 89 (71%) | 194 | 89 (72%) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ULN, upper limit of normal; URTIs, upper respiratory tract infections.

aAST ULN = 32 IU/L for women and 40 IU/L for men, ALT ULN = 40 IU/L for women and 60 IU/L for men.

bAEs and serious AEs defined using the standard International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice definition.

cAEs that do not localize to a single organ system (eg, diffuse infectious symptoms, generalized allergic reactions, electrolyte abnormalities, fatigue, insomnia, weight changes).

dIncludes melanoma.

Sixteen episodes of mild hypercalcemia (serum calcium 2.56-2.64 mmol/L) occurred in 15 participants; hypercalcemia was most frequent in the 10 000 group (P = .002 for trend), as shown in Table 2. Comparing concurrent 25OHD and PTH concentrations during episodes of hypercalcemia (n = 16) and normocalcemia (n = 2467), 25OHD concentrations were higher in states of hypercalcemia (mean [SD]: 154 [23] vs 124 [53] nmol/L, P = .02), whereas PTH concentrations were lower but not significantly different (17.3 [6.2] vs 20.2 [7.1] ng/L, P = .10) in states of hypercalcemia and normocalcemia. Twelve episodes of hypercalcemia occurred within the first 12 months, and the remaining 4 episodes occurred at month 30 (24). One participant in the 10 000 group experienced 2 episodes of transient hypercalcemia, at month 6 and month 30. Ten (67%) participants with hypercalcemia were taking a calcium supplement at the time of calcium measurement. Hypercalcemia resolved on follow-up testing in all cases; calcium intake was reduced prior to follow-up testing in 10 of these cases (this involved discontinuation of a calcium supplement in 8 cases and a decrease in dietary calcium intake in 2 cases). Two participants in the 10 000 group withdrew from the study based on hypercalcemia (24); a diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism was suspected in 1.

Hypercalciuria was observed in 4.3% of participants at baseline, none of whom had a calcium:creatinine ratio of greater than or equal to 1.0 mmol/mmol. Fig. 2 demonstrates 24-hour urine calcium excretion throughout the study. Following randomization and administration of the study intervention, 123 episodes of hypercalciuria occurred in 87 (23.3%) participants. At least 1 episode of hypercalciuria occurred in 21 (16.9%), 28 (22.4%), and 38 (30.6%) participants in the 400, 4000, and 10 000 groups, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3). Comparing concurrent 25OHD and PTH concentrations during episodes of hypercalciuria (n = 123) and normocalciuria (n = 936), 25OHD concentrations were higher (mean [SD]: 137 [55] vs 121 [50] nmol/L, P < .001) and PTH concentrations lower (17.1 [5.8] vs 20.2 [7.0] ng/L, P < .001) in states of hypercalciuria. All of these participants had a spot urine calcium:creatinine ratio less than 1.0 mmol/mmol on follow-up testing. However, recurrent episodes of elevated 24-hour urine calcium excretion were common, occurring in 5 (4.0%), 8 (6.4%), and 14 (11.3%) participants in the 400, 4000, and 10 000 groups, respectively. Timing of hypercalciuria is shown in Reference (24). No participants discontinued the study treatment because of hypercalciuria.

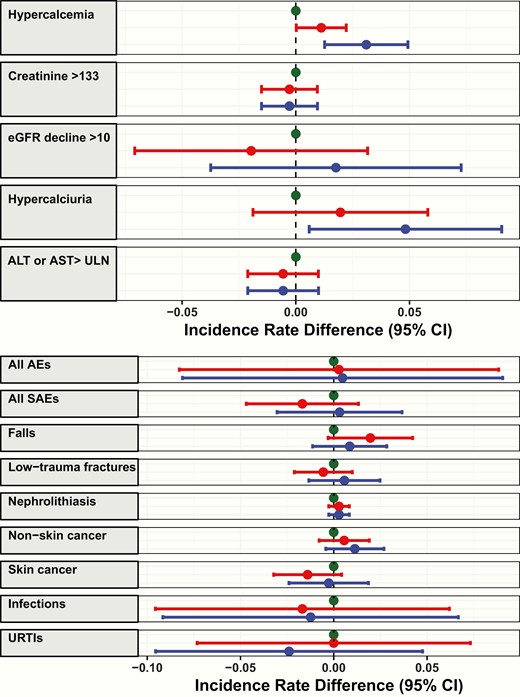

Incidence rate differences in number of healthy individuals experiencing relevant biochemical (left panel) and clinical (right panel) adverse events (AEs) while taking vitamin D 400 (green), 4000 (red), or 10 000 (blue) IU/day for 3 years, using 400 IU/day as the referent. Incidence rates reflect the number of participants experiencing the event per person-year of follow-up. Error bars represent 95% CIs. Unit of measure is μmol per liter for creatinine and mL per minute for eGFR. Nonskin cancer includes melanoma.ALT indicates alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ULN, upper limit of normal; URTIs, upper respiratory tract infections.

Incident rate differences for prespecified biochemical safety parameters, with the 400 group as the referent, are shown in Fig. 3. Informal interpretation of the CIs of the incidence rate differences agree with the formal statistical testing of the trend in proportions.

Clinical adverse events

Table 2 summarizes the clinical AEs experienced by study participants. A total of 2580 AEs were reported by 365 (97.9%) participants over 1063 person-years of follow-up. Five AEs had appropriate overall prevalence for formal statistical testing; no statistically significant between-group differences were identified (all serious AEs [P = .70], falls [P = .60], fractures [P = .43], skin cancer [P = .94], and infections [P = .19]). Clinical AEs with very low overall prevalence (nephrolithiasis [2.9%], cancer [3.2%]) or extremely high overall prevalence (all AEs [97.9%]) were not formally examined. Fig. 3 demonstrates incidence rate differences for the 8 prespecified AEs of clinical interest, with the 400 group as the referent.

Serious adverse events

Overall, 59 serious AEs occurred in 49 (13.1%) participants. These included 22 events (18 participants) in the 400 group, 16 events (12 participants) in the 4000 group, and 21 events (19 participants) in the 10 000 group. One death (presumed myocardial infarction), occurred at month 22: This was a participant in the 400 group who had discontinued the study intervention at month 15 but continued to attend follow-up visits until the time of death. The digital research repository (24) provides a summary of serious AEs.

Adverse events of special interest

Falls, low-trauma fractures, nephrolithiasis, and cancer diagnoses were considered clinical AEs of special interest. Number of falls and fractures was similar across treatment groups, as was the proportion of participants experiencing either event (Table 2). Two participants (400: 0, 4000: 1, 10 000: 1) had renal colic diagnosed. The participant from the 4000 group presented with clinical features of renal colic at month 17, at which time plain-film x-rays demonstrated a possible left-sided calculus. This participant continued the study intervention and went on to experience a second episode of renal colic at month 36, at which time computed tomography confirmed an 11 mm left-sided renal calculus. The participant from the 10 000 group presented with clinical features of renal colic at month 20, at which time computed tomography demonstrated a 3 mm left-sided renal calculus. This participant subsequently discontinued the study intervention and was moved to the intent-to-treat group. Neither of these participants had hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria at any time during the 3 years of the study, and neither passed a kidney stone. Although both had radiographic evidence of nephrolithiasis, we cannot exclude the possibility that the stones were present before study entry.

New cancer diagnoses were comparable between treatment arms (Table 2): Nineteen cases of nonmelanomatous skin cancer (24), and 12 cases of nonskin cancer (including melanoma) were diagnosed (3 gastrointestinal, 3 prostate, 2 lymphoma, 1 melanoma, 1 breast cancer, 1 bladder cancer, 1 papillary thyroid cancer).

Other adverse events of clinical relevance

Incidence of reported infections, and specifically upper respiratory tract infections, did not vary between treatment groups (Table 2). Of interest, 1 participant from the 10 000 group with psoriasis reported complete resolution of his skin lesions within 12 months of starting the study intervention.

Discussion

At very high doses, vitamin D has been associated with the development of toxicity in the form of hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, renal dysfunction, and nephrolithiasis (6, 9). In healthy adults random assigned to take vitamin D3 400, 4000 or 10 000 IU/day for 3 years, the safety profile was similar across the range of doses assessed. We observed a dose-dependent increase in incidence of hypercalcemia, although episodes were rare—affecting fewer than 5% of participants—and always transient. Hypercalciuria was also dose dependent and affected almost a quarter of participants.

Prior studies have assessed the risk of developing hypercalcemia with daily vitamin D supplementation, concluding that doses of up to 4000 IU/day are not associated with increased risk. For example, in a trial of healthy postmenopausal women (n = 2303) randomly assigned to daily supplementation with vitamin D (2000 IU/day) plus calcium (1500 mg/day) or placebo for 4 years, hypercalcemia was infrequent, occurring in 0.5% of the treatment group and 0.2% of the placebo group (25). In another study of 61 adults who were supplemented with vitamin D 1000 or 4000 IU/day for 2 to 5 months, no hypercalcemia or differences in serum calcium levels were observed (26). Conversely, in a 2016 meta-analysis of 48 trials, there was an increased risk of hypercalcemia with vitamin D supplementation compared to placebo (relative risk:1.94, 95% CI: 1.09-2.18) (27). The studies included in this meta-analysis were widely variable in terms of vitamin D formulation, dose, and administration interval, although the majority of trials evaluated vitamin D3, and the average dose studied was 2354 IU/day (27). The authors did not observe a dose-response relationship between vitamin D supplementation and risk of hypercalcemia, although the average daily vitamin D dose in the analyzed trials was much less than 4000 IU (27). Most previous studies evaluating vitamin D supplementation with more than 4000 IU/day also suggest a low incidence of hypercalcemia. For example, Heaney et al supplemented 67 healthy men with either 1000, 5500, or 11 000 IU/day vitamin D for 20 weeks and reported no episodes of hypercalcemia (11). In a study of 12 patients with multiple sclerosis treated with progressively increasing vitamin D doses up to 280 000 IU/week (average 40 000 IU/day) for 28 weeks, no cases of hypercalcemia were observed (13). Most recently, Aloia and colleagues randomly assigned 132 postmenopausal women to daily vitamin D 600 IU or 10 000 IU (all participants also received 1200 mg/day calcium as carbonate) for 1 year and found no difference in the incidence of hypercalcemia between groups (14). In the present study, median serum calcium concentrations were similar for each of the 3 vitamin D doses throughout 3 years of follow-up. Hypercalcemia was most common in participants taking vitamin D 10 000 IU/day, although episodes were infrequent, mild, and transient. Two-thirds of these episodes occurred in participants taking a calcium supplement, discontinuation of which invariably resulted in normalization of serum calcium.

The development of hypercalcemia in individuals taking vitamin D 4000 or 10 000 IU/day might be more dependent on calcium intake than on vitamin D. In their 2016 meta-analysis, Malihi and colleagues noted that hypercalcemia was more common in studies in which calcium and vitamin D supplements were coadministered, compared with studies of vitamin D alone (27). In their 12-month comparison of vitamin D 600 and 10 000 IU/day, Aloia et al (14) observed hypercalcemia in 23% of women taking vitamin D 10 000 IU/day, vs the 7% prevalence that was observed in the 10 000 IU/day group over the first 12 months of the present study. Aloia and colleagues reported a median daily calcium intake of just less than 2000 mg (1200 mg supplement plus diet), whereas our study aimed for an estimated total intake of 1200 mg daily. The resolution of hypercalcemia with reduction in calcium intake that we observed in the present study suggests that calcium intake may be a stronger mediator of the development of hypercalcemia than vitamin D intake. Our findings suggest that individuals who take high-dose vitamin D (ie, ≥ 4000 IU/day), in addition to supplemental calcium or high dietary calcium intake, should be monitored within the first year of starting this regimen, with reduction in calcium intake if hypercalcemia is observed.

High vitamin D intake has also been associated with excess urinary calcium excretion, with or without hypercalcemia (14, 27, 28). Malihi et al found an increased risk of hypercalciuria with vitamin D supplementation (relative risk:1.64, 95% CI: 1.06-2.53) (27), and Aloia and colleagues reported a higher risk of hypercalciuria in individuals randomly assigned to 10 000 IU/day compared to 600 IU/day (odds ratio: 3.6, 95% CI: 1.39-9.3) (14). In the present study, hypercalciuria was identified in 4.3% of participants at baseline, comparable with previous reports suggesting a prevalence of 5% to 10% (29). Throughout the 3-year study, prevalence of hypercalciuria was dose dependent, affecting almost one-third of the 10 000 IU/day group. Follow-up spot urine testing demonstrated that these participants invariably had urine calcium:creatinine ratios less than 1.0 mmol/mmol, indicating against the presence of severe hypercalciuria. Similarly, Kimball and colleagues did not observe elevations in urinary calcium:creatinine ratios (ie, > 1.0 mmol/mmol) in 12 adults treated with vitamin D doses of up to 280 000 IU/week for 28 weeks (13). Importantly, our results highlight a discrepancy between the 24-hour urinary calcium excretion and fasting second void calcium:creatinine ratio cutoffs chosen for the diagnosis of hypercalciuria (30); the clinical relevance of this discrepancy is uncertain, particularly in terms of long-term renal outcomes. However, as 24-hour urinary calcium excretion is more reflective of oral calcium intake (via diet and supplement) than fasting spot urine assessment—corroborated by our observation that 24-hour urinary calcium excretion normalized in most cases following reduction in calcium intake—clinicians should use 24-hour urinary calcium assessments to monitor calciuria in individuals receiving high-dose vitamin D supplements, with a view to reducing calcium intake if hypercalciuria is detected.

We did not find a higher risk of clinically relevant renal sequelae (renal dysfunction and nephrolithiasis) with increasing vitamin D dose. Although our study was not powered to detect differences in these events, which occurred infrequently, our results are in keeping with a large observational study that did not find a relationship between vitamin D intake and incident nephrolithiasis (31), as well as a 4-year interventional study of vitamin D plus calcium vs placebo in 2303 postmenopausal women that reported a similar incidence of renal calculi in the treatment group (1.4%) and the placebo group (0.9%) (25), and a recently published meta-analysis (27). In contrast, the Women’s Health Initiative demonstrated a 17% increase in the risk of nephrolithiasis with combined vitamin D (400 IU/day) and calcium carbonate (1000 mg/day) compared to placebo, with 2.5% of women in the treatment group and 2.1% of women in the placebo group reporting kidney stones over an average of 7 years of follow-up (32). Given the relatively low vitamin D dose and relatively high calcium supplement dose evaluated in the Women’s Health Initiative study, it is possible that calcium supplementation has a larger influence on kidney stone formation than vitamin D supplementation.

Intermittent administration of large doses of vitamin D (equating to average daily doses of 800 to 2000 IU) has been associated with an increased risk of falls and/or fractures in some studies (33-35) but not others (36). We did not observe a dose-dependent difference in the incidence of falls or low-trauma fractures, although both outcomes were infrequent in our population of healthy adults without osteoporosis.

A myriad of nonskeletal effects of vitamin D have been postulated (37). Specifically, vitamin D has been shown to have several immunomodulatory actions, and the possibility has been raised that vitamin D supplementation might affect the pathogenesis of immune-related conditions including infections, autoimmune disorders such as psoriasis and multiple sclerosis, and some cancers (37). For example, findings from a recent meta-analysis (38) and a systematic review of meta-analyses (37) indicate that vitamin D supplementation may protect against the development of upper respiratory tract infections, and topical vitamin D analogues have been successfully used in the treatment of psoriasis (39). However, current evidence does not support vitamin D supplementation for the prevention or treatment of other nonskeletal conditions, including cancer (37, 40, 41). In our study, we did not observe a dose-dependent effect of vitamin D supplementation on the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections, dermatologic conditions, or cancers. Cancer was diagnosed in 3.2% of our study cohort over 3 years of follow-up, comparable to the 4.7% incidence reported by Lappe et al in their 4-year study of vitamin D (2000 IU/day) plus calcium (1500 mg/d) vs placebo in healthy postmenopausal women (25). In the present study, prostate cancer was diagnosed in 3 participants taking vitamin D 10 000 IU/day, although given the long latency period of prostate cancer (15-20 years), it is unlikely that these cancers were related to the study intervention.

Cardiovascular events were balanced among intervention groups in this healthy population. Although the present study was not powered to detect differences in cardiovascular event rates, 2 recent trials have demonstrated no effect of vitamin D supplementation on the incidence of cardiovascular events (41, 42).

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, safety was a prespecified secondary outcome of this study. As such, the trial was not designed to detect rare AEs. Second, clinical AEs were elicited from participants in a passive manner, and only select clinical AEs (serious AEs, fractures, nephrolithiasis, and cancer) were adjudicated. Third, although the 3-year duration of this study was long in relation to many previous trials, vitamin D supplementation is generally commenced with a plan to be continued indefinitely, and it is possible that the safety profile may differ with longer-term supplementation. Fourth, 2 lots of the vitamin D preparation administered to the 10 000 IU/day group between months 18 and 36 suffered from degradation, limiting our ability to draw conclusions about the safety of supplementation with vitamin D 10 000 IU/day beyond 18 months, although the mean 25OHD level remained higher than the 4000 IU group at month 36. An additional limitation inherent to all studies of vitamin D supplementation is that we could not control for dietary intake (including fortified food sources) or skin synthesis via ultraviolet light exposure. However, our randomized controlled approach serves to mitigate bias introduced by these factors. It is also important to note that our study population consisted predominantly of individuals who were vitamin D sufficient (25OHD > 50 nmol/L) at baseline, and vitamin D supplementation may have a more favorable risk-to-benefit ratio in the setting of vitamin D insufficiency (40).

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the largest randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of vitamin D up to 10 000 IU/day in healthy adults for more than 12 months. More than 90% of participants completed study follow-up, with more than 99% adherence. Although not designed to detect rare AEs, the trial’s sample size permitted evaluation of the principal manifestations of vitamin D toxicity (hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, renal dysfunction) over a relatively long timeframe, and our findings thus represent a significant and necessary contribution to the literature regarding the safety of vitamin D supplementation.

Conclusions

In healthy adults who are not vitamin D deficient, daily vitamin D supplementation with doses of 400, 4000, and 10 000 IU for up to 3 years is generally safe and well tolerated, although further study is required to determine whether use of high-dose vitamin D results in any long-term sequelae. This is particularly relevant for the dose of 10 000 IU/day because participants randomly assigned to receive this dose in the present study actually received lower doses between 18 and 36 months. Supplementation for three years with up to 10 000 IU/day is associated with dose-dependent increases in hypercalciuria and with rare cases of transient hypercalcemia; these events typically resolve with reduction in calcium intake. It may be prudent for clinicians to monitor for the development of hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria in individuals taking vitamin D 4000 IU/day or more and who use calcium supplements or have high dietary calcium intake, with a view to reducing calcium intake if hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria are observed. This study does not provide any evidence of dose-dependent effects of vitamin D on fractures, falls, infections, dermatologic conditions, or cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the data safety monitoring board for their commitment to the safety of the study participants. In addition, we extend our gratitude to the men and women who participated in this trial.

Financial Support: This study was funded by Pure North S’Energy Foundation in response to an investigator-initiated research grant proposal.

Clinical Trial Information: NCT01900860 (clinicaltrials.gov)

Author Contributions: E.O.B. reviewed and adjudicated adverse events (with D.A.H.), completed the preliminary data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. L.A.B. participated in data collection and cleaning, provided input regarding data analysis and interpretation, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. M.S.R. completed the final statistical analysis, provided insights regarding data interpretation, and created Figs. 2 and 3. E.M.D. contributed to the literature review and preliminary data analysis. S.G. and M.K. were responsible for trial coordination and data collection, and both participated in creation of the manuscript. S.K.B. and D.A.H. conceived of the study idea, designed the study, oversaw data collection, provided insights regarding data analysis and interpretation, and made major intellectual contributions to the manuscript.

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: L.A.B., M.S.R., E.M.D., S.G., and M.K. have nothing to declare. E.O.B. has previously received honoraria from Amgen and Eli Lilly, and a research grant from Amgen. S.K.B. has received honoraria from Amgen and Servier, and is co-owner of Numerics88 Solutions Inc. D.A.H. has received a research grant and speaking honoraria from Amgen and a research grant from Eli Lilly.

Data Sharing: The authors commit to making relevant anonymized patient-level data available to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. Data will be available from 6 months following publication until 5 years following publication. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

References

Government of Candad.

Billington EO, Burt LA, Rose MS, et al. Data from: The Calgary Vitamin D Study: Safety of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementary Appendix. Figshare 2019. Deposited 06 October 2019. https://figshare.com/s/fbe04a69bf5758a03492.