-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jehad Almasri, Feras Zaiem, Rene Rodriguez-Gutierrez, Shrikant U Tamhane, Anoop Mohamed Iqbal, Larry J Prokop, Phyllis W Speiser, Laurence S Baskin, Irina Bancos, M Hassan Murad, Genital Reconstructive Surgery in Females With Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 103, Issue 11, November 2018, Pages 4089–4096, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-01863

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and atypical genitalia often undergo complex surgeries; however, their outcomes remain largely uncertain.

We searched several databases through 8 March 2016 for studies evaluating genital reconstructive surgery in females with CAH. Reviewers working independently and in duplicate selected and appraised the studies.

We included 29 observational studies (1178 patients, mean age at surgery, 2.7 ± 4.7 years; mostly classic CAH). After an average follow-up of 10.3 years, most patients who had undergone surgery had a female gender identity (88.7%) and were heterosexual (76.2%). Females who underwent surgery reported a sexual function score of 25.13 using the Female Sexual Function Index (maximum score, 36). Many patients continued to complain of substantial impairment of sensitivity in the clitoris, vaginal penetration difficulties, and low intercourse frequency. Most patients were sexually active, although only 48% reported comfortable intercourse. Most patients (79.4%) and treating health care professionals (71.8%) were satisfied with the surgical outcomes. Vaginal stenosis was common (27%), and other surgical complications, such as fistulas, urinary incontinence, and urinary tract infections, were less common. Data on quality of life were sparse and inconclusive.

The long-term follow-up of females with CAH who had undergone urogenital reconstructive surgery shows variable sexual function. Most patients were sexually active and satisfied with the surgical outcomes; however, some patients still complained of impairment in sexual experience and satisfaction. The certainty in the available evidence is very low.

Classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is one of the most common inherited disorders, affecting ∼1 in every 15,000 live births (1). Classic CAH is an autosomal recessive transmitted disorder due to a mutation in the CYP21A2 gene (90% to 95% of cases), which transcribes 21-hydroxylase, with a consequent defective conversion of 17-hydroxyprogesterone to 11-deoxycortisol (2, 3). Patients who are 46,XX with classic CAH are born with variable degrees of external genital ambiguity or atypia [e.g., fusion of the labia, a single opening within the introitus where the common urogenital channel exits, a recessed vagina and urethra that enter into the proximal aspect of the common urogenital sinus (confluence), and clitoromegaly] due to androgen excess during in utero development. Their internal reproductive anatomy includes a normal uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries with potential for fertility. The more severe “salt-wasting” variant presents clinically during the neonatal period. However, the “virilizing” (non–salt-wasting) variant presents during the neonatal period or later.

Optimal management requires a multidisciplinary team, including geneticists, pediatricians, endocrinologists, psychologists or psychiatrists, social workers, and surgeons, to render a detailed diagnosis and provide hormonal health, surgical procedures, mental health, and social services as necessary. The genital atypia and the often related uncertainty regarding the gender assignment can represent psychosocial trauma for the family and carries a risk of social stigma (4). For the purpose of restoring normal and functional anatomy, from the urinary, reproductive, sexual, and psychosocial perspectives, the usual treatment approach has often been genital reconstructive surgery, such as vaginoplasty, including separation of the urethra and vagina, relocation of the vaginal introitus to the perineum, and clitoroplasty for patients with more severe forms of clitoral masculinization (2, 3). These surgical procedures are technically complex and can lead to intraoperative and postoperative complications, and further subsequent corrective surgeries can be needed. The effects on the surgical outcome of the patient’s age at surgery, year of surgery, surgical technique, surgeon’s relevant experience and technical skills, and type of medical setting (e.g., academic vs community hospital) have not been well investigated. Moreover, data on the long-term outcomes of surgery remain uncertain, in part owing to the scarcity and small sample size of the studies. Better evidence would enable families and clinicians to have meaningful conversations about the potential benefits and harms of both surgical and nonsurgical approaches, thereby enabling them to arrive at more informed treatment decisions.

To support guideline development by the Endocrine Society, we conducted a systematic review of the reported data to appraise and summarize the evidence regarding quality of life, genitourinary function, and sexual and fertility outcomes for patients with CAH after genital reconstructive surgery.

Methods

The present systematic review followed an a priori established protocol that was developed in collaboration with experts from the Endocrine Society and is reported according to the standards set in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement (5).

Eligibility criteria

We searched for randomized clinical trials and comparative and noncomparative observational studies evaluating the long-term surgical outcomes of importance to patients with CAH undergoing genital reconstructive surgery. No language restriction was used. We included patients with both classic and nonclassic CAH and planned to present the results separately if feasible.

Data sources and searches

A comprehensive search of several databases was conducted from the inception of each database to 8 March 2016, without language restrictions. The databases included Ovid Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from the study’s principal investigator. Controlled vocabulary, supplemented with keywords, was used to search for studies of female genital reconstruction in CAH. The actual strategy is provided in an online repository (6).

Study selection

Reviewers working independently and in duplicate reviewed all the abstracts and selected full-text articles for a more detailed evaluation. Disagreements regarding the full-text screening were resolved by consensus. Additional references were sought from clinical experts from the Endocrine Society.

Data collection and management

Working independently and in duplicate, the reviewers used a standardized web-based form to collect information from each eligible study. For each study, we recorded the baseline clinical features of the included population, such as age, serum androgen levels, type of genital atypia, type and number of surgical procedures, patient age at the first surgery, and hospital setting (academic vs nonacademic). The outcomes of interest were quality of life (sexual and overall), genitourinary complications, fertility, and fecundity. We also evaluated the gender identity and sexual orientation of the individuals who had undergone surgery.

Risk of bias and quality of evidence

The risk of bias was assessed by reviewers working independently and in duplicate using a modified Ottawa classification for observational studies. We investigated three domains: selection, comparability, and exposure. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The quality of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE approach (grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation) (7).

Summary measures and synthesis of results

We performed a meta-analysis of the proportion of patients with each of the outcomes of interest using a random effects model (8). We used the I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity across the studies (I2 >50% indicates large heterogeneity across studies beyond that expected by chance). Statistical analysis was performed using STATA, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The supplemental material for our report is provided in an online repository (6).

Results

Characteristics of included studies

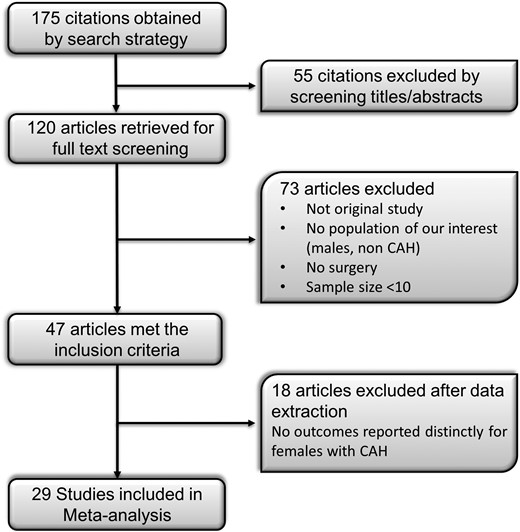

The process of study selection is depicted in Fig. 1. The initial search resulted in 175 articles, 29 of which met the inclusion criteria. The studies were from various countries: five studies were from Brazil (9–12); four from the United States (13–16); three from France (17–19); two each from the United Kingdom (20, 21), Egypt (22, 23), Germany (24, 25), Sweden (26, 27), and Turkey (28, 29); and one study each from India (30), China (31), Italy (32), Spain (33), Japan (34), Saudi Arabia (35), the Netherlands (36), and Denmark (37). The publication year ranged from 1982 to 2017. A total of 1204 patients were included, with a mean age at the initial surgery of 2.7 ± 4.7 years. In 17 studies with available follow-up data, the patients had been followed up for an average of 10.3 years (range, 0.5 to 24.4 years). Only nine studies were comparative. Specifically, two studies (21, 27) compared patients with CAH who had undergone surgery with patients with CAH who had not undergone surgery. The remaining seven studies had compared patients with CAH to healthy controls. Most patients had classic CAH, and only 13 patients in four studies (15, 21, 27, 36) had the nonclassic (late-onset) form of CAH. Of the 29 studies included in our systematic review, seven had included only adults; five had included children, adolescents and adults; and four had included adults and adolescents. All patients had undergone surgery during childhood. The baseline characteristics are provided in an online repository (6). The type of genital reconstructive surgery varied across the studies but consisted of vaginoplasty and/or clitoroplasty performed in one or two stages.

The outcomes of interest are presented descriptively and graphically in an online repository (6). A meta-analysis was feasible only by pooling the event rates at the end of the follow-up as proportions. The main conclusions from the available comparative, nonrandomized studies are summarized in an online repository (6).

Gender identity and sexual orientation

Data from two studies (17, 30) showed that 88.7% (63 of 71) of the patients had a female gender identity. Gupta et al. (30) in 2006 found that four of 50 patients had a male gender identity. Data from three studies (16, 17, 30) showed that 15 of the 115 subjects had a mixed gender identity. Binet et al. (17) found that 76.2% (16 of 21) of the patients were heterosexual and three were bisexual. Data from four studies (17, 18, 32, 36) showed that 16.3% of the patients identified themselves as homosexual (6).

Surgical outcomes

Sexual function

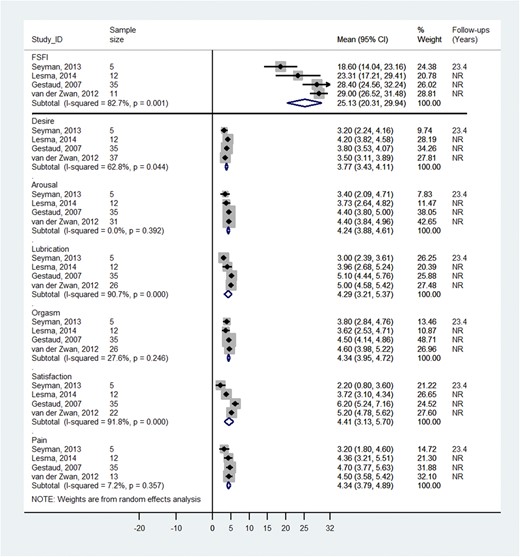

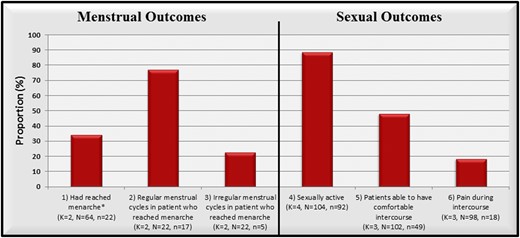

Eleven studies provided data that could be used in the meta-analysis. The mean Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) score among 63 patients across four studies (18, 32, 35, 36) was 25.13 (95% CI, 20.31 to 29.94; I2 = 82.7%). The FSFI values can range from 2 to 36. The mean scores of each of the subcomponents of the FSFI ranged from 3.77 to 4.41 (maximum score for each component, 6). The results are shown in Fig. 2. One study (18) reported significantly lower FSFI scores in women with CAH women who had undergone surgery than in healthy controls. In contrast, three other studies (32, 35, 36) showed no substantial difference compared with the healthy controls. The Golombok-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction score was used in one study (21), and the score ranged from four to eight in the surgical group and from one to six in the healthy control group. In the same study, the females who had undergone surgery continued to complain of substantial impairment in the sensitivity of the clitoris, vaginal penetration difficulties, and intercourse frequency. In another study (26), the mean McCoy score was 34.7 ± 10 for the surgical group compared with 37.2 ± 6.3 in the control group. Most patients (88.5%) were sexually active postoperatively [four studies (16–18, 25)]; however, only 48% reported comfortable intercourse [three studies (13, 14, 36)]. Detailed results are presented in an online repository (6) and Fig. 3.

Total and subcomponent mean FSFI scores after surgery and length of follow-up. Higher FSFI values indicate better function. Possible range of FSFI scores: total score, 2 to 36; subcomponent “desire,” 1.2 to 6.0; subcomponent “satisfaction,” 0.8 to 6.0; subcomponents “arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and pain,” 0 to 6.0. NR, not reported.

Proportion of patients with specific menstrual and sexual outcomes. (Proportions do not sum to 100% because each outcome measure was derived from a different group of studies). K, number of studies; N, total sample size; n, total number of events.

Menstrual function and fertility

Two studies (20, 30) evaluated 64 patients and showed that 34% had achieved menarche and 77% had regular menstrual periods (Fig. 3). Data from four studies showed that 22.4% (15 of 67) of the women became pregnant.

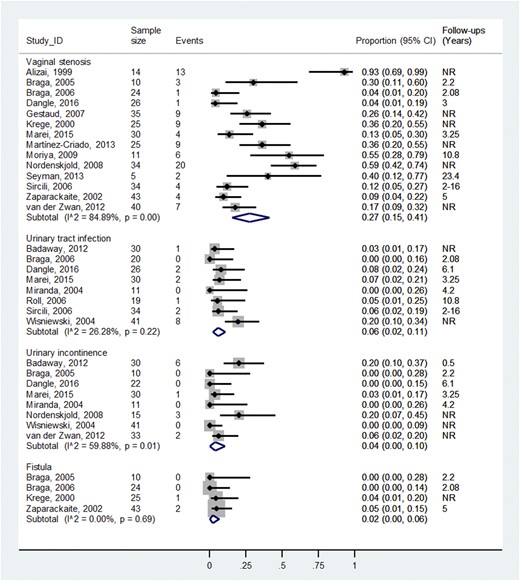

Complications (vaginal stenosis and urinary complaints)

Fourteen studies reported the incidence of vaginal stenosis (rate, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.41; I2 = 85%). The occurrence of urinary tract infection was reported in eight studies (rate, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.11; I2 = 26%). Urinary incontinence was reported in eight studies (rate, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.0 to 0.10; I2 = 60%). Fistulas were reported in four studies (rate, 0.02; 95% CI, 0.0 to 0.06; Fig. 4). Data on additional genitourinary complications are provided in an online repository (6).

Proportion of patients with vaginal stenosis or urinary tract complications and length of follow-up. NR, not reported.

Overall satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes of surgery

Patient satisfaction with surgical outcomes was reported in two studies (25, 33) and averaged 79.4%. The satisfaction of the treating physicians with the surgical outcomes was reported in five studies (9, 12, 25, 31, 35) and averaged 71.8% (6).

Quality of life

In a study by Martinez et al. (33), 5 of 15 patients reported that they required psychological support. In another study by Gupta et al. (30), only 3 of 42 patients (age >5 years) reported that they were emotionally insecure and described themselves as “sick.” Data from four studies showed that 8.8% (13 of 147) of the women had gotten married.

Quality of evidence

The studies had an overall moderate to high risk of bias owing to the absence of a comparison (69% of the included studies) and small sample sizes. The selection and exposure quality domains were poorly reported across the studies, and they were well documented in only 24% and 28% of the studies, respectively. Of the 29 studies, 12 included retrospective cohorts, 10 studies included prospective cohorts, and 7 were case-control studies. Therefore, the quality of evidence (i.e., certainty in the estimates) was very low overall across all outcomes owing to imprecision, methodological limitations, and inconsistency.

Discussion

Main findings

We have systematically reviewed the available body of evidence on the outcomes of genital reconstructive surgery in female patients with CAH. Although the data consisted of case series and retrospective comparisons, several inferences are possible. After an average follow-up of 10 years, females who had undergone surgery reported a sexual function score of 25.13 using the FSFI (maximum score, 36), which suggests residual difficulties. The studies showed that many of these females continued to complain of substantial impairment of sensitivity in the clitoris, vaginal penetration difficulties, and decreased intercourse frequency. Most patients were sexually active, although only one in two patients reported comfortable intercourse. More than 70% of the patients and treating health care professionals were satisfied with the surgical outcomes. Surgical complications, such as fistulas, urinary incontinence, and urinary tract infections, were uncommon; however, vaginal stenosis was as common as one in four patients. Most patients had a female gender identity and were heterosexual. Finally, data on quality of life were sparse.

Limitations and strengths

The available data were observational in nature and did not provide comparisons of surgical timing or techniques. Therefore, the present systematic review should not be viewed as providing comparative effectiveness evidence. Rather, we have provided the best available summary of the postoperative surgical outcomes as expected for an average follow-up of series of patients with heterogeneous disease severity who were treated with heterogeneous surgical techniques. The summarized evidence can serve as a starting point for discussions with patients and families contemplating genital reconstructive surgery for CAH. It is plausible that patients undergoing surgery who were included in the reported studies were those patients who had been more severely affected, making the results less applicable to less severe cases. The available evidence does not allow for comparisons of surgical skill or volume, nor were data found comparing patients who had undergone surgery before 1982 with those who had undergone procedures performed using newer techniques in the past two decades.

The strengths of the present review relate to the comprehensive literature search, the a priori established protocol, and the rigorous and reproducible process of study selection and appraisal.

Implications

Families with females with CAH who are severely virilized should be informed about the available surgical and nonsurgical options. If surgery is pursued, shared decision-making is essential to allow families and patients to choose the approach most consistent with their values and preferences. Issues to discuss should include the expected outcomes based on the available data, the uncertainty about such outcomes, and the availability of surgical expertise and centers with adequate volumes. Delaying surgery until the child is older is possible depending on the location of the urogenital confluence of the vagina and urethra. A multidisciplinary team of surgeons, pediatric endocrinologists, and mental health professionals is needed to optimize patient care and patient experience.

Conclusion

Long-term follow-up data of females with CAH who had undergone urogenital reconstructive surgery showed variable sexual function. Most patients were sexually active and satisfied with the surgical outcomes, although some patients still reported impairment in sexual experience and satisfaction. Many patients continued to report substantial impairment. Surgical complications, such as fistulas, urinary incontinence, and urinary tract infections, were uncommon. However, vaginal stenosis was frequent. Finally, data on patients’ quality of life were sparse.

Abbreviations:

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The present study was funded by the Endocrine Society (to M.H.M.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.