-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Na Li, Ruya Liu, Huijie Zhang, Jun Yang, Shouyue Sun, Manna Zhang, Yuejun Liu, Yan Lu, Wei Wang, Yiming Mu, Guang Ning, Xiaoying Li, Seven Novel DAX1 Mutations with Loss of Function Identified in Chinese Patients with Congenital Adrenal Hypoplasia, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 95, Issue 9, 1 September 2010, Pages E104–E111, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2408

Close - Share Icon Share

Context:DAX1 (for dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia congenital critical region on the X chromosome, gene 1; also called NROB1) mutations are responsible for adrenal failure and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in patients with adrenal hypoplasia congenita (AHC), through a loss of trans-repression of SF-1 (for steroidogenic factor-1)-mediated StAR (for steroidogenic acute regulatory protein) and LHβ transcriptional activities and a reduction of GnRH expression. The correlation of clinical features with genetic and functional alterations of the gene was investigated in detail in AHC patients.

Objective: The present study aimed at identifying DAX1 mutations in Chinese AHC patients and investigating the functional defects of detected novel mutations.

Patients and Methods: Nine patients with AHC were recruited from eight families. DAX1 mutations were screened, and the transcriptional activities of the identified mutations were assessed in vitro.

Results:DAX1 mutations were detected in all nine patients enrolled in the study, with eight different mutations. Among the latter, seven are novel mutations, including two missense (L262P and C368F), one nonsense (Q222X), and four frame-shift (637delC, 652_653delAC, 973delC, and 774_775insCC) mutations. The functional studies showed that the mutant DAX1 was impaired by nuclear localization, loss of trans-repression of StAR and LHβ transcriptional activities, and reduction of GnRH expression.

Conclusion: These findings provide insight into the molecular events by which DAX1 mutations influence the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and lead to AHC and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita (AHC) is a rare inherited disorder of adrenal gland development, characterized by absence or near absence of the permanent zone of the adrenal cortex (1). Patients with this condition usually present with primary adrenal failure in infancy or early in childhood, including salt-wasting, hyperpigmentation, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, reduction of serum glucocorticoid and aldosterone, and increase of plasma ACTH (1). This disease is lethal without appropriate steroid hormone replacement. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HHG), which is usually recognized at the expected time of puberty, is commonly associated with the X-linked AHC. HHG is caused by abnormalities of gonadotropin production in both hypothalamus and pituitary (2) and requires testosterone replacement for sexual maturity (3). Mutations in DAX1 (for dosage-sensitive sex reversal, adrenal hypoplasia congenital critical region on the X chromosome, gene 1; also called NROB1) gene in chromosome Xp21 are responsible for the X-linked AHC/HHG (1, 4).

The DAX1 gene is composed of two exons separated by a single intron (1, 3) and encodes a 470 amino acid unusual orphan nuclear receptor that is structurally related to the ligand binding domain localized in the carboxyl terminus of other nuclear receptors but lacks the typical zinc finger DNA-binding domain in the amino terminus. Instead, the amino terminus consists of 3.5 alanine/glycine-rich repeats of a 65–70 amino acid motif that is implicated in protein-protein interactions (5) and may bind to hairpin loop structure in DNA (6). DAX1 expression has been shown in the developing adrenal cortex, gonad, anterior pituitary, and hypothalamus and also in adult adrenal cortex, anterior pituitary gonadotropes, the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus, Sertoli and Leydig cells in the testis, and theca and granulose cells in the ovary (7, 8). DAX1 plays a predominant role as a transcriptional repressor in gonadal and adrenal development and in the regulation of gonadotropin production (9). In particular, there is overwhelming evidence for an interaction of DAX1 with the nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1/NR5A1/Ad4BP) (10–12) and repression of SF-1-mediated transactivation (10). SF-1 belongs to the NR5A subfamily of orphan nuclear receptors and plays critical roles in the regulation of sex determination, adrenal and gonadal developments, reproductive function, and steroidogenesis (11, 13). It seems paradoxical that SF-1 loss-of-function mutations also result in adrenal hypoplasia in mice (11). However, in humans, SF-1 mutations rarely produce adrenal hypoplasia (12). Although it has been reported that DAX1 can form coactivator complexes that increase the expression of a subset of steroidogenic genes in the adrenal and gonadal cells (14, 15) or interact with SF-1 in upregulating PBX1 to participate in adrenal development (16), the exact mechanisms remain unclear. DAX1 has also been proposed to act as a nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling protein in interaction with ribonucleoprotein structures in the nucleus and polyribosomes in the cytoplasm (17), raising the possibility that it plays an additional regulatory role in posttranscriptional processes.

To date, more than 100 different mutations in DAX1 have been described, most of which are nonsense or frame-shift mutations that cause premature truncation of the protein. Most of the missense mutations clustered at the carboxyl terminus, and only a few were reported at the amino terminus (15, 18). In the present study, we identified seven novel DAX1 mutations in eight patients from seven different families and found altered DAX1 functions caused by these mutations. Our data may provide insight into the molecular events by which DAX1 mutations influence the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis and lead to AHC and HHG, respectively.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Nine patients with AHC and HHG were recruited from the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Rui-Jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and the Beijing Chinese PLA General Hospital during March 2006 to June 2009.

Patients I and II were cousins, and the other seven patients were unrelated. The symptoms and physical findings were ascertained by senior endocrinologists. The clinical characteristics and blood biochemical examinations were shown in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1 (published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). Most patients presented with salt-losing and adrenal insufficiency in the early age and lack of development of secondary sexual characteristics at the expected time of puberty.

| Patient . | Age at presentation/mode of presentation . | Age at diagnosis/mode of presentation . | ACTH (ng/liter) . | Cortisol (μg/liter) . | Aldosterone (ng/liter) . | PRA (μg/liter · h) . | LH (IU/liter) . | T (μg/liter) . | DAX1 mutations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | 8 yr/vomiting, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 18 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2500 | 8.1 | 0.10 | 32.3 | 0.51 | 0.3 | L262P |

| IIa | At birth/hyperpigmentation, repeated vomiting, fever, fatigue, and poor feeding | 10 yr and 9 months/no development of secondary sexual characteristics | 220 | 26.2 | 59.60 | 16.49 | <0.07 | 0.1 | L262P |

| IIIb | 8 yr/fatigue, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and progressive hyperpigmentation | 23 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 926 | 9.3 | 65.83 | UD | 0.79 | <0.08 | C368F |

| IVc | At birth/hyperpigmentation, poor feeding, and Apgar score of 0 | 27 yr/no development of secondary characteristics, fatigue, or mental retardation | 3195 | 97 | 17.80 | 3.44 | 0.62 | <0.08 | 637delC; codon 213 (stop codon 263) |

| Vd | At birth/poor feeding, jaundice, progressive hyperpigmentation, and Apgar score of 0 | 6 months/UD | 1738 | 26 | 27.3 | 6.58 | UD | 1.35 | 652_653delAC; condon 218 (stop codon 297) |

| VIe | 10 yr/progressive fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 20 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 4530 | 46 | 25.90 | 11.17 | 0.24 | <0.08 | 973delC; codon325 (stop codon 371) |

| VIIf | 2 yr/anorexia, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 15 yr/poor development of secondary characteristics | 11.8 | 17.2 | 21 | 5.20 | <0.07 | 0.09 | 774_775insCC; codon 259 (stop codon 264) |

| VIIIg | 5 yr/repeated nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain | 17 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2565.3 | 13.6 | UD | UD | <0.07 | 0.14 | L278P |

| IXh | 11 yr/dizziness, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 26 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 1195.9 | 68 | 12.5 | 2.6 | 0.19 | <0.08 | Q222X |

| Patient . | Age at presentation/mode of presentation . | Age at diagnosis/mode of presentation . | ACTH (ng/liter) . | Cortisol (μg/liter) . | Aldosterone (ng/liter) . | PRA (μg/liter · h) . | LH (IU/liter) . | T (μg/liter) . | DAX1 mutations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | 8 yr/vomiting, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 18 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2500 | 8.1 | 0.10 | 32.3 | 0.51 | 0.3 | L262P |

| IIa | At birth/hyperpigmentation, repeated vomiting, fever, fatigue, and poor feeding | 10 yr and 9 months/no development of secondary sexual characteristics | 220 | 26.2 | 59.60 | 16.49 | <0.07 | 0.1 | L262P |

| IIIb | 8 yr/fatigue, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and progressive hyperpigmentation | 23 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 926 | 9.3 | 65.83 | UD | 0.79 | <0.08 | C368F |

| IVc | At birth/hyperpigmentation, poor feeding, and Apgar score of 0 | 27 yr/no development of secondary characteristics, fatigue, or mental retardation | 3195 | 97 | 17.80 | 3.44 | 0.62 | <0.08 | 637delC; codon 213 (stop codon 263) |

| Vd | At birth/poor feeding, jaundice, progressive hyperpigmentation, and Apgar score of 0 | 6 months/UD | 1738 | 26 | 27.3 | 6.58 | UD | 1.35 | 652_653delAC; condon 218 (stop codon 297) |

| VIe | 10 yr/progressive fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 20 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 4530 | 46 | 25.90 | 11.17 | 0.24 | <0.08 | 973delC; codon325 (stop codon 371) |

| VIIf | 2 yr/anorexia, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 15 yr/poor development of secondary characteristics | 11.8 | 17.2 | 21 | 5.20 | <0.07 | 0.09 | 774_775insCC; codon 259 (stop codon 264) |

| VIIIg | 5 yr/repeated nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain | 17 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2565.3 | 13.6 | UD | UD | <0.07 | 0.14 | L278P |

| IXh | 11 yr/dizziness, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 26 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 1195.9 | 68 | 12.5 | 2.6 | 0.19 | <0.08 | Q222X |

Normal range, adult: ACTH, 12–78 ng/liter; cortisol, 70–220 μg/liter; aldosterone, 29.4–161.5 ng/liter; PRA, 0.1–5.5 μg/liter · h; LH, 1.3–10.1 IU/liter; T, 1.8–8.4 μg/liter. Normal range, children: LH, 1–18 months, 0.04–3.01 IU/liter; 10–11 yr, 0.03–4.44 IU/liter; 15–18 yr, 0.69–7.15 IU/liter; T, 5–7 months (≦0.59 μg/liter; 10–11 yr, 0.05–0.5 μg/liter; 15–17 yr, 2.2–8 μg/liter. Serum biochemical measurements obtained at diagnosis. PRA, plasma renin activity; T, testosterone; UD, undetermined.

Patients I and II were cousins. Patient I received hydrocortisone when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 8 yr until now. Patient II received cortisone acetate when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 2 yr and changed to hydrocortisone at age of 5 yr until now.

Patient III received hydrocortisone (10 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 8 yr. Hydrocortisone was increased to 20 mg/d at age of 14 yr.

Patient IV received hydrocortisone when adrenal insufficiency (21-hydroxylase deficiency) was diagnosed at birth (dose unclear) and hydrocortisone at 10 mg/d until the age of 27 yr when he presented with loss of salt, including elevated serum potassium (8.1 mm) and low serum sodium(123.0 mm). He has started to receive 9-αflurohydrocortisone (100 μg/d) and hydrocortisone (60 mg/d) since then.

Patient V received hydrocortisone (10 mg/d) and fludrocortisones (0.025 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency (21-hydroxylase deficiency) was diagnosed at birth and hydrocortisone (10 mg/d) and 9-αflurohydrocortisone (50 μg/d) until the age of 6 months.

Patient VI did not receive treatment.

Patient VII received hydrocortisone (20 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 7 yr and a gradual increase to 40 mg/d until the age of 15 yr.

Patient VIII received cortisone acetate (12.5 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 6 yr and cortisone acetate (37.5 mg/d) now.

Patient IX received prednisone (10 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 11 yr and an increase to 15 mg because of fatigue at age of 24 yr. An irregular medication was considered because his plasma ACTH was 1195.9 ng/liter when he received 15 mg prednisone. He has started to receive cortisone acetate at 37.5 mg/d since then.

| Patient . | Age at presentation/mode of presentation . | Age at diagnosis/mode of presentation . | ACTH (ng/liter) . | Cortisol (μg/liter) . | Aldosterone (ng/liter) . | PRA (μg/liter · h) . | LH (IU/liter) . | T (μg/liter) . | DAX1 mutations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | 8 yr/vomiting, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 18 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2500 | 8.1 | 0.10 | 32.3 | 0.51 | 0.3 | L262P |

| IIa | At birth/hyperpigmentation, repeated vomiting, fever, fatigue, and poor feeding | 10 yr and 9 months/no development of secondary sexual characteristics | 220 | 26.2 | 59.60 | 16.49 | <0.07 | 0.1 | L262P |

| IIIb | 8 yr/fatigue, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and progressive hyperpigmentation | 23 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 926 | 9.3 | 65.83 | UD | 0.79 | <0.08 | C368F |

| IVc | At birth/hyperpigmentation, poor feeding, and Apgar score of 0 | 27 yr/no development of secondary characteristics, fatigue, or mental retardation | 3195 | 97 | 17.80 | 3.44 | 0.62 | <0.08 | 637delC; codon 213 (stop codon 263) |

| Vd | At birth/poor feeding, jaundice, progressive hyperpigmentation, and Apgar score of 0 | 6 months/UD | 1738 | 26 | 27.3 | 6.58 | UD | 1.35 | 652_653delAC; condon 218 (stop codon 297) |

| VIe | 10 yr/progressive fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 20 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 4530 | 46 | 25.90 | 11.17 | 0.24 | <0.08 | 973delC; codon325 (stop codon 371) |

| VIIf | 2 yr/anorexia, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 15 yr/poor development of secondary characteristics | 11.8 | 17.2 | 21 | 5.20 | <0.07 | 0.09 | 774_775insCC; codon 259 (stop codon 264) |

| VIIIg | 5 yr/repeated nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain | 17 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2565.3 | 13.6 | UD | UD | <0.07 | 0.14 | L278P |

| IXh | 11 yr/dizziness, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 26 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 1195.9 | 68 | 12.5 | 2.6 | 0.19 | <0.08 | Q222X |

| Patient . | Age at presentation/mode of presentation . | Age at diagnosis/mode of presentation . | ACTH (ng/liter) . | Cortisol (μg/liter) . | Aldosterone (ng/liter) . | PRA (μg/liter · h) . | LH (IU/liter) . | T (μg/liter) . | DAX1 mutations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | 8 yr/vomiting, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 18 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2500 | 8.1 | 0.10 | 32.3 | 0.51 | 0.3 | L262P |

| IIa | At birth/hyperpigmentation, repeated vomiting, fever, fatigue, and poor feeding | 10 yr and 9 months/no development of secondary sexual characteristics | 220 | 26.2 | 59.60 | 16.49 | <0.07 | 0.1 | L262P |

| IIIb | 8 yr/fatigue, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and progressive hyperpigmentation | 23 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 926 | 9.3 | 65.83 | UD | 0.79 | <0.08 | C368F |

| IVc | At birth/hyperpigmentation, poor feeding, and Apgar score of 0 | 27 yr/no development of secondary characteristics, fatigue, or mental retardation | 3195 | 97 | 17.80 | 3.44 | 0.62 | <0.08 | 637delC; codon 213 (stop codon 263) |

| Vd | At birth/poor feeding, jaundice, progressive hyperpigmentation, and Apgar score of 0 | 6 months/UD | 1738 | 26 | 27.3 | 6.58 | UD | 1.35 | 652_653delAC; condon 218 (stop codon 297) |

| VIe | 10 yr/progressive fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 20 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 4530 | 46 | 25.90 | 11.17 | 0.24 | <0.08 | 973delC; codon325 (stop codon 371) |

| VIIf | 2 yr/anorexia, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation, | 15 yr/poor development of secondary characteristics | 11.8 | 17.2 | 21 | 5.20 | <0.07 | 0.09 | 774_775insCC; codon 259 (stop codon 264) |

| VIIIg | 5 yr/repeated nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain | 17 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 2565.3 | 13.6 | UD | UD | <0.07 | 0.14 | L278P |

| IXh | 11 yr/dizziness, fatigue, and hyperpigmentation | 26 yr/no development of secondary characteristics | 1195.9 | 68 | 12.5 | 2.6 | 0.19 | <0.08 | Q222X |

Normal range, adult: ACTH, 12–78 ng/liter; cortisol, 70–220 μg/liter; aldosterone, 29.4–161.5 ng/liter; PRA, 0.1–5.5 μg/liter · h; LH, 1.3–10.1 IU/liter; T, 1.8–8.4 μg/liter. Normal range, children: LH, 1–18 months, 0.04–3.01 IU/liter; 10–11 yr, 0.03–4.44 IU/liter; 15–18 yr, 0.69–7.15 IU/liter; T, 5–7 months (≦0.59 μg/liter; 10–11 yr, 0.05–0.5 μg/liter; 15–17 yr, 2.2–8 μg/liter. Serum biochemical measurements obtained at diagnosis. PRA, plasma renin activity; T, testosterone; UD, undetermined.

Patients I and II were cousins. Patient I received hydrocortisone when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 8 yr until now. Patient II received cortisone acetate when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 2 yr and changed to hydrocortisone at age of 5 yr until now.

Patient III received hydrocortisone (10 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 8 yr. Hydrocortisone was increased to 20 mg/d at age of 14 yr.

Patient IV received hydrocortisone when adrenal insufficiency (21-hydroxylase deficiency) was diagnosed at birth (dose unclear) and hydrocortisone at 10 mg/d until the age of 27 yr when he presented with loss of salt, including elevated serum potassium (8.1 mm) and low serum sodium(123.0 mm). He has started to receive 9-αflurohydrocortisone (100 μg/d) and hydrocortisone (60 mg/d) since then.

Patient V received hydrocortisone (10 mg/d) and fludrocortisones (0.025 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency (21-hydroxylase deficiency) was diagnosed at birth and hydrocortisone (10 mg/d) and 9-αflurohydrocortisone (50 μg/d) until the age of 6 months.

Patient VI did not receive treatment.

Patient VII received hydrocortisone (20 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 7 yr and a gradual increase to 40 mg/d until the age of 15 yr.

Patient VIII received cortisone acetate (12.5 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 6 yr and cortisone acetate (37.5 mg/d) now.

Patient IX received prednisone (10 mg/d) when adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed at age of 11 yr and an increase to 15 mg because of fatigue at age of 24 yr. An irregular medication was considered because his plasma ACTH was 1195.9 ng/liter when he received 15 mg prednisone. He has started to receive cortisone acetate at 37.5 mg/d since then.

The patients were also subject to adrenal computed tomography scan and GnRH stimulating tests (Supplemental Table 1). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Rui-Jin Hospital. The informed consent was obtained from each participant.

DNA sequence analysis

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using the Puregene kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Both DAX1 (NC_000023, cDNA, NM_000475) exons and flanking intronic sequence were amplified using the following sets of forward and reverse primers: exon 1 forward, 5′ GAGGTCATGGGCGAACAC; exon 1 reverse, 5′ TGCTGAGTTAGTCACGATTTCT; exon 2 forward, 5′ AGCAAAGGACTCTGTGGT; and exon 2 reverse, 5′ GAGCTATGCTACCTGTTG.

PCR was performed in a final volume of 50 μl reaction system containing 200 ng genomic DNA, 20 pmol of each primer, 200 μm dNTPs, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 2.5 U Taq polymerase (Sangon, Shanghai, China). Exon 1 was amplified by an initial denaturation at 95 C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 C for 30 sec, annealing at 53 C for 30 sec, and elongation at 72 C for 1.5 min, with a final extension at 72 C for 10 min. Exon 2 was amplified by an initial denaturation at 95 C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 C for 30 sec, annealing at 50 C for 30 sec, and elongation at 72 C for 45 sec, with a final extension step at 72 C for 10 min. Direct DNA sequencing in both directions was performed using an automated sequencer (ABI Prism 3700 DNA Analyzer; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Generation of DAX1 and SF-1 expression vectors

Full-length DAX1 cDNA was generated from human pituitary tissues by RT-PCR and inserted into pcDNA3.1/V5-His TOPO and pEGFP-C1 expression vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), respectively. The mutants R267P, L262P, C368F, 637delC, and 652_653delAC were created by site-directed mutagenesis using the KOD-Plus (Toyobo Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) for long PCR and DpnI (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) for digestion. The full-length SF-1 cDNA was also obtained from human pituitary tissues and inserted into pcDNA3.1/myc-His (−) C (Invitrogen), and the full-length early growth response-1 (Egr-1) cDNA was amplified from mouse liver tissues. All the novel amplified cDNAs were confirmed by direct sequencing.

Cell culture and transient transfection

The human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T, the mouse adrenal cell line Y1, and the mouse GnRH secreting cell line GT1-7 were used in this study. HEK293T and GT1-7 cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 C. Y1 cells were grown in F12 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 C.

HEK293T cells, Y1 cells, and GT1-7 cells were seeded on 24-well plates and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Luciferase assay

StAR luciferase reporter (StAR-luc) contains the sequence −965 to +261 bp of the promoter of human steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene. LHβ-luc contains the sequence −154 to +5 bp (15) of the native rat LHβ promoter. GnRH-luc contains the sequence −1008 to +17 bp of human GnRH promoter, which was not different by luciferase activity from the longer rat promoter (−3026/+116 bp). The sequence −535 to −479 bp of hGnRH promoter is crucial in transcriptional activity in vivo and in vitro (19).

Y1 cells were cotransfected with 400 ng StAR-luc, 20 ng Renilla luciferase reporter pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI), and 400 ng wild-type (WT) or mutant DAX1. Forskolin (10 μm) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or DMSO (10 μm) was added 36 h after transfection, and luciferase assays were performed 12 h after treatment using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the instructions of the manufacturer with a luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA). The use of the second plasmid reporter that encodes for Renilla luciferase under the control of thymidine kinase promoter conveniently allows for the normalization of all results according to the transfection efficiency of each individual sample within the same luciferase assay. In addition, DAX1 repression of SF-1-mediated LHβ transcriptional activation was examined in HEK293T cells with cotransfection of 200 ng LHβ-luc, 20 ng pRL-TK, 200 ng SF-1, 400 ng Egr-1, and 500 ng WT or mutant DAX1. Luciferase assays were performed 24 h after transfection. GT1-7 cells were transfected with 80 ng GnRH-luc, 5 ng pRL-SV40, which was also used as an internal control for transfection efficiency, 40 ng SF-1, and WT or mutant DAX1 (10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ng). Cells were harvested 36 h after transfection, and luciferase activity was then measured.

Total DNA was kept constant by complementing each transfection with empty backbone plasmids whenever it was necessary. The readings were reported as a fold of the empty vector control to allow comparison of the data from different experiments. The results were represented as mean ± sem from at least three independent experiments. Each experiment was performed in triplicate transfections.

Subcellular localization and Western blot

HEK293T cells were seeded on poly-lysine (Sigma)-coated coverslips in 24-well plates and transfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged WT or various mutants. At 24 h after transfection, cells were washed three times with PBS and mounted on slides with antifade mountant (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The images were captured using an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) system.

HEK293T cells were seeded in six-well plates and transfected with 4 μg GFP-tagged WT or various mutants. Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted, respectively, using a nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents; Pierce, Rockford, IL) at 24 h after transfection according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Equal amounts of proteins (30 μg) were solubilized in sample buffer, loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) using standard methods. Membranes were probed with specific antibodies that recognize GFP-tagged DAX1 and various mutants (1:2000, anti-GFP; Sigma), tubulin (1:2000, anti-Tubulin; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and lamin B (1:1000, anti-Lamin B; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After 2 h incubation at room temperature with primary antibodies, the membranes were washed and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The rabbit secondary antibody for GFP and tubulin (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology) and the goat for lamin B (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used. The specific bands were visualized by the ECL system (Amersham ECL plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). Tubulin and lamin B were used as cytoplasmic and nuclear loading controls, respectively.

Results

Identification of DAX1 mutations

Direct sequencing was used to characterize DAX1 mutation in nine patients whose clinical characteristics and blood biochemical examinations were shown in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1. The results showed that DAX1 mutations were identified in all the tested patients, including three missense, four frame-shift, and one nonsense mutations (Table 1). L262P mutation was detected in patients I and II from the same family. Two missense mutations (L262P and C368F), one nonsense mutation (Q222X), and four frame-shift mutations (637delC, 652_653delAC, 973delC, and 774_775insCC) were not reported previously. The sequencing results were shown in Supplemental Fig. 1.

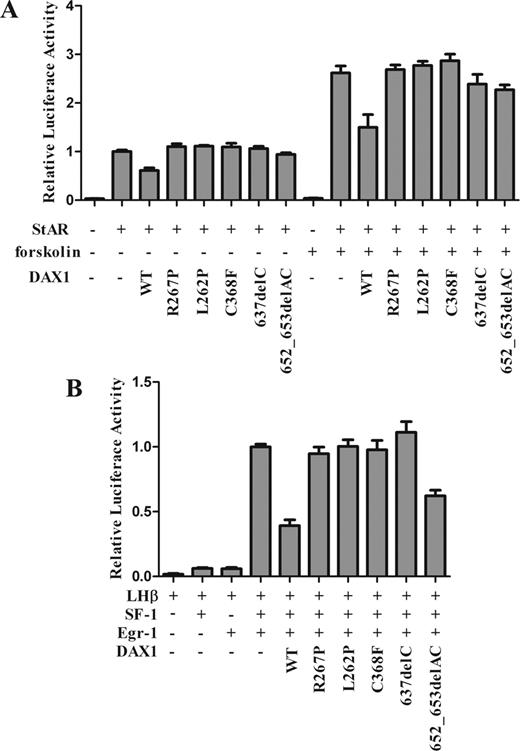

Loss of repressor function

DAX1 has been shown to function primarily as a transcription repressor. Therefore, we investigated whether DAX1 mutations derived from those patients led to loss of repressor function. It was reported previously that DAX1 repressed StAR expression by binding to a hairpin in the StAR promoter (Fig. 1B) (6). We examined, therefore, DAX1-mediated repression on the human StAR promoter, which can be induced by cAMP (6), using WT DAX1 and a “classic” AHC mutant, R267P. We transfected steroidogenic Y1 cells with the StAR promoter and observed a 2.7-fold increase when induced by forskolin treatment (P < 0.0005) (Fig. 1A). WT DAX1 repressed both basal and cAMP-induced promoter activities by 39 and 44%, respectively (P < 0.005), whereas the mutated DAX1 totally lost the repression function of both basal and forskolin-induced StAR expression.

Luciferase assay for StAR and LHβ transcriptional activities. A, Mutant DAX1 loss of trans-repression for StAR transcriptional activity. Y1 cells were cotransfected with human StAR-luc (400 ng) and full-length human WT or mutant DAX1 (400 ng) and treated with or without forskolin (10 μm). WT DAX1 suppressed StAR transcriptional activity, whereas mutant DAX1 dramatically lost this repression with or without forskolin treatment. Mutant 652_653delAC only showed a partial loss of repression. B, Mutant DAX1 loss of repression for SF-1-mediated LHβ transcriptional activity. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with rat LHβ-luc (−154 to +5 bp, 200 ng), full-length SF-1 (200 ng), full-length Egr-1 (400 ng), and full-length WT or mutant DAX1 (500 ng). The mutant DAX1 completely lost the suppression of LHβ transcriptional activity. Mutant 652_653delAC also showed a partial loss of repression. WT DAX1 and a classic AHC mutant, R267P, were used as controls. The total amount of DNA was constant by complementing with empty backbone plasmid if necessary. Results were represented as a percentage of the empty DAX1 vectors and as the mean ± sem from at least three independent experiments.

LHβ gene promoter, which could be up-regulated by SF-1 and down-regulated by DAX1 via interaction with SF-1, was next adopted to assess the change of repressor function of newly found mutant DAX1. This promoter contains two composite SF-1/Egr-1 binding sites, which allows synergistic activation of LHβ gene by these transcription factors (20). Overexpression of SF-1 and Egr-1 resulted in a 25-fold increase of LHβ transcription. WT DAX1 significantly suppressed SF-1-mediated transcription by 63% (P < 0.01), whereas the DAX1 mutants R267P, L262P, C368F, and 637delC completely lost the repression function of SF-1-mediated LHβ transcription. However, the DAX1 mutant 652_653delAC showed a partial repression by 38% (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B).

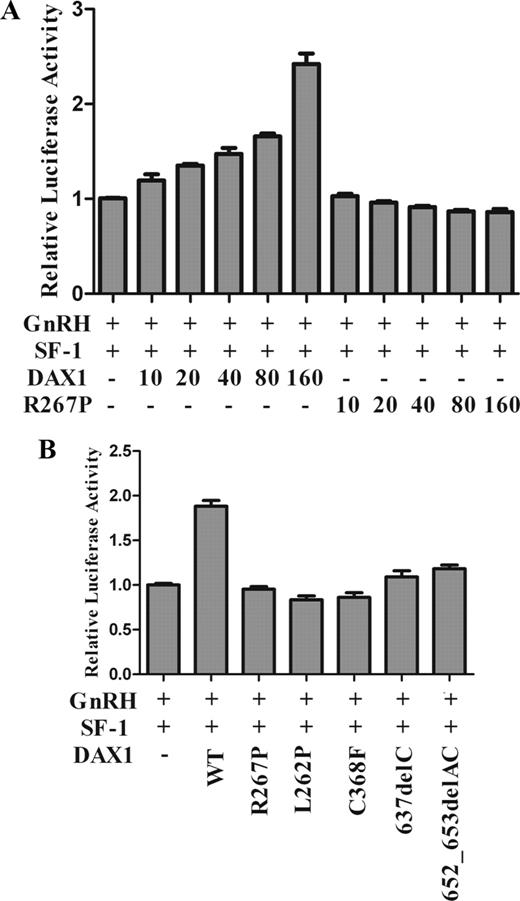

GnRH expression reduction by DAX1 mutants

To investigate the mechanism of HHG in AHC patients, we further examined GnRH expression by luciferase assay. We transfected GT1-7 cells with the hGnRH promoter and WT or mutant DAX1. The results showed that GnRH expression was dramatically increased by WT DAX1 in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of SF-1 but not by DAX1 mutants R267P, L262P, C368F, 637delC, and 652_653delAC (Fig. 2, A and B).

Luciferase assay for GnRH transcriptional activity. GT1-7 cells were transfected with human GnRH promoter (−1008 to +17 bp, 80 ng) and full-length SF-1 (40 ng) and full-length WT or mutant DAX1. A, A titration of DAX1 plasmid (10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ng) was used. The pRL-SV40 was used as an internal control for transfection efficiency. B, GT1-7 cells were transfected with WT and mutant DAX1 (160 ng) and SF-1 (40 ng). The results are represented as the fold of the empty vector control and as the mean ± sem from at least three independent experiments.

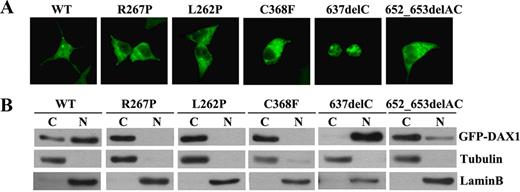

Subcellular localization of DAX1 mutants

It was reported that DAX1 mutations led to abnormal nuclear localization and consequently impaired transcriptional repression activity (21–23). DAX1 is exclusively localized in the nuclei in tissues such as the gonads, adrenal cortex, pituitary, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (24, 25), and prostate (17). HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with either GFP-tagged WT DAX1 or the mutants R267P, L262P, C368F, 637delC, or 652_653delAC. GFP fusion fluorescence and Western blots showed that DAX1 was predominantly localized in the nuclei, whereas the mutants R267P, L262P, and C368F were exclusively localized in cytoplasm (Fig. 3, A and B). However, the mutant 637delC was mainly located in the nuclei. Compared with the WT DAX1, the mutant 652_653delAC showed a major cytoplasmic localization and a slight nuclear localization. The subcellular localization assay was also performed in adrenal Y1, HeLa, and CHO cells, which confirmed the observation seen in HEK293T cells (data not shown).

Subcellular localization of mutant DAX1. HEK293T cells were transfected with GFP-tagged WT or mutant DAX1. A, GFP fusion fluorescence. WT DAX1 is predominantly located in the nuclei, whereas DAX1 mutants R267P, L262P, C368F, and 652_653delAC were exclusively located in cytoplasm. Mutant 637delC was mainly located in the nuclei. B, Western blotting. Cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) proteins were isolated and loaded. Tubulin and lamin B were used as loading controls, respectively.

Discussion

X-linked AHC is typically caused by the mutation of orphan nuclear receptor gene DAX1, which is characterized by primary adrenal insufficiency associated with HHG. In the present study, we identified seven novel DAX1 mutations and one previously reported mutation (L278P) (26) in nine AHC patients. Of the seven novel mutations, two are missense (L262P and C368F), one is nonsense (Q222X), and four are frame-shift (637delC, 652_653delAC, 973delC, and 774_775insCC) mutations. Three patients with mutations L262P, 637delC, and 652_653delAC presented with salt-wasting at neonatal, whereas six with mutations L262P, C368F, 973delC, 774_775insCC, L278P, and Q222X had their onset at child AHC and HHG. Of note, AHC presenting adrenal insufficiency should be differentiated from 21-hydroxylase deficiency or Addison’s disease secondary to multiple etiologies. Distinguishing these disorders is important because they differ in their clinical courses, steroid replacement, prognosis, and genetic counseling. It has been reported that DAX1 mutations were found in 58% boys (neonatal to 13 yr old) with primary adrenal insufficiency for unknown etiology, in which common causes of adrenal failure such as steroidogenic defects (e.g. 21-hydroxylase deficiency) and metabolic disorders (e.g. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy) had been excluded (27). Therefore, it is necessary to detect DAX1 mutations for definitive diagnosis of the patient presented with salt-wasting states, when common causes of adrenal failure and metabolic disorders had been excluded.

The previous studies as well as ours affirm a phenotypic heterogeneity associated with DAX1 mutations (15, 18). However, there is a trend for genotype-phenotype correlations to occur within families (28), although the younger brother is usually diagnosed at a younger age as in patients I and II. The absence of genotype-phenotype correlations for certain DAX1 mutations is presumably caused by the influence of other genes modifying or compensating for DAX1 function (29, 30). Alternatively, it may also be explained by the need of the entire DAX1 structure or dispersed protein domains for its normal function. It should also be recognized, however, that all of these transcriptional assays were performed in vitro and might not sufficiently reflect the functions of DAX1 in vivo. It has been reported that extracellular matrix and hormones can modulate DAX1 localization in the human fetal adrenal gland (31) and consequently affect the function of DAX1, which suggests that DAX1 may have tissue-specific functions.

The StAR protein is an indispensable component in regulating steroid hormone biosynthesis. DAX1 acts as a powerful transcriptional repressor of StAR gene expression (6), leading to a drastic decrease in steroid production. Our results showed that DAX1 mutations led to loss of repression of StAR expression (Fig. 1). Repression of StAR expression in the adrenal cortex by DAX1 may be a prerequisite for proliferation of the definitive zone in the critical postnatal period in humans. It was speculated that, in the presence of a DAX1 complete inactivation, the genes involved in steroid hormone production were abnormally activated in adrenal-definitive zone cells at an earlier stage. This process would impair their proliferation and further zonation (32). It was also reported that DAX1 knockdown in mouse embryonic stem cells induced loss of pluripotency and multilineage differentiation (33). As a result, loss of DAX1 repression of StAR expression leads to adrenal hypoplasia and subsequently causes the low levels of serum steroid hormones. Moreover, patients with DAX1 mutations always presented with low serum LH levels at puberty. We found that SF-1-mediated LHβ transactivation was suppressed by DAX1 but not by DAX1 mutants (Fig. 1). Apparently, the change of LHβ expression did not participate in the HHG in AHC patients (Table 1). We further investigated the DAX1 regulation of GnRH expression in the hypothalamus. GnRH, a key regulator of reproduction, is released from the hypothalamic neurons and triggers the synthesis and release of pituitary LH and FSH, which are responsible for gonadal steroidogenesis and gametogenesis (34). Our results indicated that DAX1 increased GnRH expression in the presence of SF-1 in a dose-dependent manner, whereas the DAX1 mutants did not (Fig. 2, A and B). Thus, HHG in AHC patients could be mainly caused by GnRH down-regulation attributable to DAX1 mutations.

To further explore the molecular mechanism of loss of function, DAX1 subcellular localization was examined. We found that DAX1 mutants R267P, L262P, and C368F were exclusively located in cytoplasm, whereas the 652_653delAC mutant showed a small amount of nucleus accumulation, corresponding to the repression ability. The 637delC mutant also exhibited a complete loss of repression ability, although it was still located in nuclei (Fig. 3). Together, there are two possible explanations for this. First, it is possible that protein misfolding caused by R267P, L262P, or C368F mutation may impact the interaction of DAX1 with other shuttle proteins such as estrogen receptors α and β besides SF-1 (22, 35), which could also transport DAX1 into the nucleus (18). In addition, misfolded proteins may expose new molecular surfaces, subsequently interact with cytoplasmic anchoring sites, and remain in the cytoplasm (32). Interestingly, the misfolding of DAX1 proteins may also explain their reduced interaction with ribonucleoprotein structures in the nucleus and polyribosomes in the cytoplasm (17). Consequently, transcription repression ability is impaired. The second possibility is related to altered C terminus as a result of novel 637delC and 652_653delAC mutations. Because the two mutations lose the whole C terminus of DAX1, it is proposed that the intact C terminus is critical in determining DAX1 subcellular localization (21) and also acts as a trans-repression domain (36) as well as an interaction domain with the corepressors N-coR (37) and Alien (38). The two altered C terminus may have certain additional functions, including nuclear localization and trans-repression.

In conclusion, seven novel DAX1 mutations were identified in patients with AHC and HHG and led to loss of repression of SF-1-mediated StAR and LHβ expression. Moreover, we found that DAX1 mutation resulted in a reduction of GnRH expression, which is associated with HHG. The present study provides insight into the molecular events by which DAX1 mutations influence the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and lead to AHC and HHG.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Chang-Xian Zhang (Faculté de Médecine Domaine Rockefeller, Université Lyon 1, Lyon, France) for the critical reading of this manuscript. We thank G. Yan for technical assistance and J. Larry Jameson’s laboratory (Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Molecular Medicine, Northwestern University, The Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL) and Mingyao Liu’s laboratory (The Institute of Biomedical Sciences and School of Life Sciences, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China) for the generous gifts of the Lhβ promoter construct and GnRH promoter construct, respectively. We are very grateful to the subjects and their families for their cooperation.

This work was supported by Shanghai Committee for Science and Technology Grants 09DJ1400402 and 09XD1403400 and National Nature Science Foundation Grants 30725037 and 30971386.

N.L. and R.L. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure Summary: We declare that we have no conflicts of interests.

Abbreviations:

- AHC,

Adrenal hypoplasia congenital;

- Egr-1,

early growth response-1;

- GFP,

green fluorescent protein;

- HHG,

hypogonadotropic hypogonadism;

- SF-1,

steroidogenic factor-1;

- StAR,

steroidogenic acute regulatory protein;

- WT,

wild-type.