-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Celia Cardozo, Guillermo Cuervo, Miguel Salavert, Paloma Merino, Francesca Gioia, Mario Fernández-Ruiz, Luis E López-Cortés, Laura Escolá-Vergé, Miguel Montejo, Patricia Muñoz, Manuela Aguilar-Guisado, Pedro Puerta-Alcalde, Mariona Tasias, Alba Ruiz-Gaitán, Fernando González, Mireia Puig-Asensio, Antonio Vena, Francesc Marco, Javier Pemán, Jesús Fortún, José María Aguado, Benito Almirante, Alejandro Soriano, Jordi Carratalá, Carolina Garcia-Vidal, GEMICOMED (SEIMC) and the Spanish CANDI-Bundle Group , An evidence-based bundle improves the quality of care and outcomes of patients with candidaemia, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 75, Issue 3, March 2020, Pages 730–737, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz491

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Candidaemia is a leading cause of bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients all over the world. It remains associated with high mortality.

To assess the impact of implementing an evidence-based package of measures (bundle) on the quality of care and outcomes of candidaemia.

A systematic review of the literature was performed to identify measures related to better outcomes in candidaemia. Eight quality-of-care indicators (QCIs) were identified and a set of written recommendations (early treatment, echinocandins in septic shock, source control, follow-up blood culture, ophthalmoscopy, echocardiography, de-escalation, length of treatment) was prospectively implemented. The study was performed in 11 tertiary hospitals in Spain. A quasi-experimental design before and during bundle implementation (September 2016 to February 2018) was used. For the pre-intervention period, data from the prospective national surveillance were used (May 2010 to April 2011).

A total of 385 and 263 episodes were included in the pre-intervention and intervention groups, respectively. Adherence to all QCIs improved in the intervention group. The intervention group had a decrease in early (OR 0.46; 95% CI 0.23–0.89; P = 0.022) and overall (OR 0.61; 95% CI 0.4–0.94; P = 0.023) mortality after controlling for potential confounders.

Implementing a structured, evidence-based intervention bundle significantly improved patient care and early and overall mortality in patients with candidaemia. Institutions should embrace this objective strategy and use the bundle as a means to measure high-quality medical care of patients.

Introduction

Candidaemia is a leading cause of bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients worldwide. It is associated with significant morbidity, prolonged hospital stays and increased healthcare costs.1,2 In spite of advances made in diagnosis and therapy, overall mortality related to this disease is still estimated to be around 30%–65%, and has not varied significantly in recent years.2–4

Some key points for clinical management of candidaemia have been identified. These critical issues include timely and appropriate selection of empirical and targeted therapies, source control measures and actions related to identifying cases of complicated candidaemia.5–12 Although these measures are included in the most recent IDSA and ESCMID management guidelines, the frequency with which these recommendations are implemented in routine practice varies. As a result, practices both within and across hospitals are inconsistent.13–15

We performed a quasi-experimental study, comparing the outcomes of patients with candidaemia from a previous population-based prospective cohort with those of a more recent cohort involving the same hospitals after the implementation of a structured, evidence-based intervention bundle. We aimed to study whether performing such an intervention would be useful in improving the quality of care and outcomes of patients affected.4

Materials and methods

Identification of quality-of-care indicators (QCIs) for candidaemia management

A systematic review of the literature was performed to identify the best evidence on aspects that had a significant influence on prognosis in adult patients related to the clinical management of candidaemia (a search of this nature was last done on 1 September 2016). Studies were evaluated from 1989 to 2016, and included the following populations: critical, neutropenic and non-neutropenic. Studies were retrieved from the PubMed database using the following search terms: candida AND candidaemia AND invasive candidiasis OR bloodstream infection OR sepsis AND outcome OR complications OR mortality OR death OR recurrence. Observational and randomized studies were selected if the two following criteria were fulfilled: predictors or risk factors for outcome determinants (including rates of clinical cure, microbiological cure, mortality, complications or recurrence) were studied; and accepted methods for control of confounding factors were used in the case of observational studies (including multivariate or stratified analysis or matching). The studies were reviewed by three investigators (G.C., C.G.-V. and C.C.). Variables independently and consistently (e.g. they were found in at least two studies) related to outcome, and amenable to clinical intervention, were selected as QCIs. A formula to measure the level of adherence to the indicator was defined for each one. Definitions of QCIs are detailed in Table 1.

Bundle recommendations and definitions of QCIs for candidaemia as selected from literature

| QCI . | Definition . | Formula . | Reference no. Supplementary data . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |||

| (a) Early adequate antifungal therapy | Within first 72 h after positive blood culture. | Adequate intravenous antifungal therapy (within 72 h) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 1–48 |

| (b) Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock | Initial treatment with echinocandins in patients with septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU. | Initial therapy (first 48 h) with echinocandins × 100/septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU patients alive at 48 h. | 6, 42, 49–54 |

| (c) Early source control | Drainage of abscess within 72 h of positive blood culture or CVC removal. | Patients with early source control (<72 h) × 100/patients with a source suitable for drainage or CVC removal. | 6, 10–12, 15, 21, 32–34, 36, 37, 39, 51, 55–70 |

| Identification of complicated candidaemia | |||

| (a) Follow-up blood culture | Perform blood cultures every 48 h after starting antifungal therapy and until clearance of candidaemia. | Patients with follow-up blood culture (after 48 h of treatment) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 16, 36, 38, 58, 71–74 |

| (b) Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | Ophthalmoscopic evaluation in every patient. | Patients in whom an ophthalmoscopic evaluation was performed × 100/patients. | 75–77 |

| (c) Echocardiography | Performance of echocardiography in patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factor for endocarditis. | Patients in whom echocardiography was performed × 100/patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factors for endocarditis (alive at least at 96 h). | 78, 79 |

| Treatment adequacy | |||

| (a) De-escalate therapy | De-escalation antifungal therapy. | De-escalation antifungal therapy × 100/patients with an isolated species susceptible to de-escalation antifungal therapy within 3 days. | 80–83 |

| (b) Adequate length of antifungal treatment | At least 14 days of treatment since last positive blood culture in uncomplicated candidaemia (or more as required by complicated candidaemia). | Patients with correct length of treatment × 100/patients alive at 14 days (28 days in complicated candidaemia). | 84–94 |

| QCI . | Definition . | Formula . | Reference no. Supplementary data . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |||

| (a) Early adequate antifungal therapy | Within first 72 h after positive blood culture. | Adequate intravenous antifungal therapy (within 72 h) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 1–48 |

| (b) Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock | Initial treatment with echinocandins in patients with septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU. | Initial therapy (first 48 h) with echinocandins × 100/septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU patients alive at 48 h. | 6, 42, 49–54 |

| (c) Early source control | Drainage of abscess within 72 h of positive blood culture or CVC removal. | Patients with early source control (<72 h) × 100/patients with a source suitable for drainage or CVC removal. | 6, 10–12, 15, 21, 32–34, 36, 37, 39, 51, 55–70 |

| Identification of complicated candidaemia | |||

| (a) Follow-up blood culture | Perform blood cultures every 48 h after starting antifungal therapy and until clearance of candidaemia. | Patients with follow-up blood culture (after 48 h of treatment) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 16, 36, 38, 58, 71–74 |

| (b) Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | Ophthalmoscopic evaluation in every patient. | Patients in whom an ophthalmoscopic evaluation was performed × 100/patients. | 75–77 |

| (c) Echocardiography | Performance of echocardiography in patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factor for endocarditis. | Patients in whom echocardiography was performed × 100/patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factors for endocarditis (alive at least at 96 h). | 78, 79 |

| Treatment adequacy | |||

| (a) De-escalate therapy | De-escalation antifungal therapy. | De-escalation antifungal therapy × 100/patients with an isolated species susceptible to de-escalation antifungal therapy within 3 days. | 80–83 |

| (b) Adequate length of antifungal treatment | At least 14 days of treatment since last positive blood culture in uncomplicated candidaemia (or more as required by complicated candidaemia). | Patients with correct length of treatment × 100/patients alive at 14 days (28 days in complicated candidaemia). | 84–94 |

Bundle recommendations and definitions of QCIs for candidaemia as selected from literature

| QCI . | Definition . | Formula . | Reference no. Supplementary data . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |||

| (a) Early adequate antifungal therapy | Within first 72 h after positive blood culture. | Adequate intravenous antifungal therapy (within 72 h) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 1–48 |

| (b) Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock | Initial treatment with echinocandins in patients with septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU. | Initial therapy (first 48 h) with echinocandins × 100/septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU patients alive at 48 h. | 6, 42, 49–54 |

| (c) Early source control | Drainage of abscess within 72 h of positive blood culture or CVC removal. | Patients with early source control (<72 h) × 100/patients with a source suitable for drainage or CVC removal. | 6, 10–12, 15, 21, 32–34, 36, 37, 39, 51, 55–70 |

| Identification of complicated candidaemia | |||

| (a) Follow-up blood culture | Perform blood cultures every 48 h after starting antifungal therapy and until clearance of candidaemia. | Patients with follow-up blood culture (after 48 h of treatment) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 16, 36, 38, 58, 71–74 |

| (b) Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | Ophthalmoscopic evaluation in every patient. | Patients in whom an ophthalmoscopic evaluation was performed × 100/patients. | 75–77 |

| (c) Echocardiography | Performance of echocardiography in patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factor for endocarditis. | Patients in whom echocardiography was performed × 100/patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factors for endocarditis (alive at least at 96 h). | 78, 79 |

| Treatment adequacy | |||

| (a) De-escalate therapy | De-escalation antifungal therapy. | De-escalation antifungal therapy × 100/patients with an isolated species susceptible to de-escalation antifungal therapy within 3 days. | 80–83 |

| (b) Adequate length of antifungal treatment | At least 14 days of treatment since last positive blood culture in uncomplicated candidaemia (or more as required by complicated candidaemia). | Patients with correct length of treatment × 100/patients alive at 14 days (28 days in complicated candidaemia). | 84–94 |

| QCI . | Definition . | Formula . | Reference no. Supplementary data . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |||

| (a) Early adequate antifungal therapy | Within first 72 h after positive blood culture. | Adequate intravenous antifungal therapy (within 72 h) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 1–48 |

| (b) Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock | Initial treatment with echinocandins in patients with septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU. | Initial therapy (first 48 h) with echinocandins × 100/septic shock or severely ill patients in ICU patients alive at 48 h. | 6, 42, 49–54 |

| (c) Early source control | Drainage of abscess within 72 h of positive blood culture or CVC removal. | Patients with early source control (<72 h) × 100/patients with a source suitable for drainage or CVC removal. | 6, 10–12, 15, 21, 32–34, 36, 37, 39, 51, 55–70 |

| Identification of complicated candidaemia | |||

| (a) Follow-up blood culture | Perform blood cultures every 48 h after starting antifungal therapy and until clearance of candidaemia. | Patients with follow-up blood culture (after 48 h of treatment) × 100/patients alive at 48 h. | 16, 36, 38, 58, 71–74 |

| (b) Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | Ophthalmoscopic evaluation in every patient. | Patients in whom an ophthalmoscopic evaluation was performed × 100/patients. | 75–77 |

| (c) Echocardiography | Performance of echocardiography in patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factor for endocarditis. | Patients in whom echocardiography was performed × 100/patients with complicated candidaemia or cardiological risk factors for endocarditis (alive at least at 96 h). | 78, 79 |

| Treatment adequacy | |||

| (a) De-escalate therapy | De-escalation antifungal therapy. | De-escalation antifungal therapy × 100/patients with an isolated species susceptible to de-escalation antifungal therapy within 3 days. | 80–83 |

| (b) Adequate length of antifungal treatment | At least 14 days of treatment since last positive blood culture in uncomplicated candidaemia (or more as required by complicated candidaemia). | Patients with correct length of treatment × 100/patients alive at 14 days (28 days in complicated candidaemia). | 84–94 |

Study design, setting, data collection and description of pre-intervention and intervention periods

The study was performed in 11 tertiary hospitals (all of them with active transplant programmes and ICUs) in Spain. A quasi-experimental design before and during the implementation of the intervention was used. For the pre-intervention group, data were used from a prospective multicentre population-based surveillance programme on candidaemia conducted in five metropolitan areas of Spain from May 2010 to April 2011. Clinical data were prospectively recorded using a standardized case report form as described elsewhere.4 For the intervention group, between September 2016 and February 2018 infectious disease specialists at each of the same hospitals implemented written recommendations for the eight aspects selected as QCIs in a structured form (bundle). The details of the bundle are given in the Supplementary data (available at JAC Online).

Most researchers were the same in both periods. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria, data collection and patients’ follow-up were used for both periods. All episodes of candidaemia involving admitted patients >17 years of age were considered eligible. Mixed candidaemia, defined as the isolation of two different Candida species in a blood culture, was included. Patients were identified through daily review of microbiology reports. Only one episode per patient (the first) was included, except in cases when a later episode was separated from the prior one by an interval of >30 days and without evidence of recurrence from a deep-seated source of infection. Patients who died in the first 48 h (who were not subject to intervention) and those receiving palliative care for terminal conditions were excluded. Those patients who did not consent to being included in the study were also excluded.

The following information was collected from medical records: demographic characteristics; underlying conditions; clinical characteristics at onset, including severity scores, source of infection, causative species, systemic antifungal therapy and susceptibility to antifungals; and outcome. Patient data were collected by a non-blinded investigator in each of the participating hospitals. Hereafter, the groups are referred to as the pre-intervention and intervention groups. All patients were monitored until discharge or death and were assessed for survival and recurrence on days 30 and 90 during a visit to the outpatient clinic or by phone call.

Primary and secondary endpoints and definitions

The main outcome variable of the quasi-experimental study was adherence to the eight QCIs selected, measured as the proportion of cases in which the recommended action was performed. Early (10 day) and overall (30 day) all-cause mortalities were considered as secondary outcome variables.

The Charlson index was used to represent comorbidity in adults. Septic shock, defined as sustained hypotension and requirement for vasoactive support, was recorded on the day of candidaemia. Acute severity of illness was assessed using the Pitt bacteraemia score. Timing related to central venous catheter (CVC) removal and antifungal administration was the interval between diagnostic blood culture and measure implementation. A simple score for estimating the risk of candidaemia caused by fluconazole non-susceptible strains was provided to each centre (Flu-NS prediction score). The items evaluated in this score are: transplant recipient status; hospitalization in a unit with a high prevalence (15%) of fluconazole non-susceptible strains; and previous azole therapy for at least 3 days.16 Catheter-related candidaemia was defined as when there was at least one positive peripheral blood culture and one of the following findings: (i) a positive semi-quantitative or quantitative catheter-tip culture that grew the Candida found in the peripheral blood; or (ii) a positive paired central and peripheral blood culture that grew the same Candida, the former blood culture having been positive ≥2 h earlier. Episodes with no defined secondary source or without proven catheter-related origin were classified as primary candidaemia. We considered adequate early antifungal treatment as appropriate if at least one active drug according to in vitro susceptibility results had been given within the first 72 h after the blood culture was obtained. Not administering an empirical treatment was considered an inappropriate treatment. Patients receiving >3 days of systemic antifungal drug before the first positive blood culture were considered to have breakthrough candidaemias. Persistent candidaemia was defined as any positive blood culture taken after ≥2 days from the first ones, yielding the same species of Candida in patients receiving active antifungal treatment. In candidaemia due to fluconazole-susceptible strains and initial antifungal therapy other than fluconazole, we recommended changing to fluconazole (de-escalation) after 3 days, if the patient was stable.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are reported as median and IQR and qualitative variables as number (%). Categorical data were analysed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test; continuous variables were compared by the Mann–Whitney U-test. Median improvement in percentage and relative risk of adherence to QCIs were calculated with 95% CI in the pre-intervention and intervention groups. Prognostic factors associated with early and overall mortality were assessed using logistic regression. Those models were constructed using all variables significantly associated with mortality in univariate analyses. Model adequacy was assessed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was used to measure the predictive ability of the models. Potential confounders were investigated. Significance was set at a P value of <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft SPSS-PC+, version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics

This quasi-experimental study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic (HCB/2016/0544). To protect personal privacy, identifying information in the electronic database was encrypted for each patient. Informed consent was obtained before inclusion in each case.

Results

Selection of QCIs

Systematic review of the literature showed over 2000 articles. Out of this collection, 94 were selected (see references in Supplementary data). Eight components related to clinical management were chosen as QCIs. The definitions of QCIs and the formulae used to measure them are shown in Table 1.

Patients

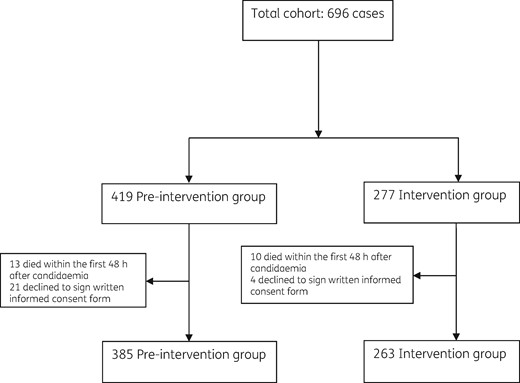

We assessed 696 consecutive adults with candidaemia for eligibility: 419 in the pre-intervention group and 277 in the intervention group. Of these, 34 (8%) and 14 (5%) episodes were excluded, respectively, with a final total of 385 and 263 episodes actually included. Figure 1 details the study flow chart.

Table 2 summarizes patients’ epidemiological and clinical characteristics in both periods. In the intervention group, patients had chronic kidney failure, chronic liver disease and chronic lung disease less frequently, and shock at onset more frequently compared with patients in the pre-intervention group. Candidaemia arose more commonly from abdominal and catheter-related sources in the intervention group in comparison with the pre-intervention group.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients in pre-intervention and intervention groups

| Characteristic . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| median age, years (IQR) | 67 (55–76.9) | 67.3 (54.3–76.8) | 67 (56–77) | 0.655 |

| male sex | 375 (58%) | 218 (56.6%) | 157 (59.9%) | 0.418 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| diabetes mellitus | 173 (26.9%) | 94 (24.4%) | 79 (30.5%) | 0.103 |

| chronic kidney failure | 134 (20.9%) | 92 (23.9%) | 42 (16.3%) | 0.023 |

| chronic liver disease | 92 (14.3%) | 67 (17.4%) | 25 (9.7%) | 0.008 |

| chronic lung disease | 118 (18.3%) | 83 (21.6%) | 35 (13.5%) | 0.010 |

| haematological malignancy | 40 (6.2%) | 27 (7%) | 13 (4.9%) | 0.321 |

| solid organ malignancy | 243 (37.6%) | 143 (37.2%) | 100 (38.2%) | 0.869 |

| HSCT | 36 (7%) | 27 (10.5%) | 9 (3.5%) | 0.002 |

| solid organ transplantation | 55 (8.5%) | 32 (8.3%) | 23 (8.9%) | 0.89 |

| HIV infection | 12 (1.9%) | 10 (2.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0.137 |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 465 (71.9%) | 284 (74%) | 181 (68.8%) | 0.156 |

| Risk factors for candidaemia | ||||

| central venous catheter | 477 (73.6%) | 299 (77.7%) | 178 (67.7%) | 0.005 |

| neutropenia | 29 (4.5%) | 21 (5.5%) | 8 (3.2%) | 0.243 |

| prior surgery (last month) | 367 (57%) | 222 (57.7%) | 145 (56%) | 0.686 |

| total parenteral nutrition | 290 (48.4%) | 162 (47.8%) | 128 (49.2%) | 0.742 |

| prior corticoid therapy | 166 (25.7%) | 114 (29.6%) | 52 (19.9%) | 0.006 |

| Source of candidaemia | ||||

| primary | 275 (43.4%) | 208 (54%) | 67 (27%) | <0.001 |

| catheter related | 253 (39.8%) | 137 (35.6%) | 116 (46.2%) | 0.008 |

| urinary | 47 (7.5%) | 27 (7%) | 20 (8.2%) | 0.646 |

| abdominal | 43 (7%) | 10 (2.7%) | 33 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Severity of infection | ||||

| Pitt score >2 | 178 (29.6%) | 106 (31.4%) | 72 (27.4%) | 0.322 |

| shock at onset | 200 (30.9%) | 104 (27%) | 96 (36.5%) | 0.012 |

| persistent candidaemia | 125 (20.4%) | 73 (19.6%) | 52 (20.6%) | 0.760 |

| Characteristic . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| median age, years (IQR) | 67 (55–76.9) | 67.3 (54.3–76.8) | 67 (56–77) | 0.655 |

| male sex | 375 (58%) | 218 (56.6%) | 157 (59.9%) | 0.418 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| diabetes mellitus | 173 (26.9%) | 94 (24.4%) | 79 (30.5%) | 0.103 |

| chronic kidney failure | 134 (20.9%) | 92 (23.9%) | 42 (16.3%) | 0.023 |

| chronic liver disease | 92 (14.3%) | 67 (17.4%) | 25 (9.7%) | 0.008 |

| chronic lung disease | 118 (18.3%) | 83 (21.6%) | 35 (13.5%) | 0.010 |

| haematological malignancy | 40 (6.2%) | 27 (7%) | 13 (4.9%) | 0.321 |

| solid organ malignancy | 243 (37.6%) | 143 (37.2%) | 100 (38.2%) | 0.869 |

| HSCT | 36 (7%) | 27 (10.5%) | 9 (3.5%) | 0.002 |

| solid organ transplantation | 55 (8.5%) | 32 (8.3%) | 23 (8.9%) | 0.89 |

| HIV infection | 12 (1.9%) | 10 (2.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0.137 |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 465 (71.9%) | 284 (74%) | 181 (68.8%) | 0.156 |

| Risk factors for candidaemia | ||||

| central venous catheter | 477 (73.6%) | 299 (77.7%) | 178 (67.7%) | 0.005 |

| neutropenia | 29 (4.5%) | 21 (5.5%) | 8 (3.2%) | 0.243 |

| prior surgery (last month) | 367 (57%) | 222 (57.7%) | 145 (56%) | 0.686 |

| total parenteral nutrition | 290 (48.4%) | 162 (47.8%) | 128 (49.2%) | 0.742 |

| prior corticoid therapy | 166 (25.7%) | 114 (29.6%) | 52 (19.9%) | 0.006 |

| Source of candidaemia | ||||

| primary | 275 (43.4%) | 208 (54%) | 67 (27%) | <0.001 |

| catheter related | 253 (39.8%) | 137 (35.6%) | 116 (46.2%) | 0.008 |

| urinary | 47 (7.5%) | 27 (7%) | 20 (8.2%) | 0.646 |

| abdominal | 43 (7%) | 10 (2.7%) | 33 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Severity of infection | ||||

| Pitt score >2 | 178 (29.6%) | 106 (31.4%) | 72 (27.4%) | 0.322 |

| shock at onset | 200 (30.9%) | 104 (27%) | 96 (36.5%) | 0.012 |

| persistent candidaemia | 125 (20.4%) | 73 (19.6%) | 52 (20.6%) | 0.760 |

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients in pre-intervention and intervention groups

| Characteristic . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| median age, years (IQR) | 67 (55–76.9) | 67.3 (54.3–76.8) | 67 (56–77) | 0.655 |

| male sex | 375 (58%) | 218 (56.6%) | 157 (59.9%) | 0.418 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| diabetes mellitus | 173 (26.9%) | 94 (24.4%) | 79 (30.5%) | 0.103 |

| chronic kidney failure | 134 (20.9%) | 92 (23.9%) | 42 (16.3%) | 0.023 |

| chronic liver disease | 92 (14.3%) | 67 (17.4%) | 25 (9.7%) | 0.008 |

| chronic lung disease | 118 (18.3%) | 83 (21.6%) | 35 (13.5%) | 0.010 |

| haematological malignancy | 40 (6.2%) | 27 (7%) | 13 (4.9%) | 0.321 |

| solid organ malignancy | 243 (37.6%) | 143 (37.2%) | 100 (38.2%) | 0.869 |

| HSCT | 36 (7%) | 27 (10.5%) | 9 (3.5%) | 0.002 |

| solid organ transplantation | 55 (8.5%) | 32 (8.3%) | 23 (8.9%) | 0.89 |

| HIV infection | 12 (1.9%) | 10 (2.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0.137 |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 465 (71.9%) | 284 (74%) | 181 (68.8%) | 0.156 |

| Risk factors for candidaemia | ||||

| central venous catheter | 477 (73.6%) | 299 (77.7%) | 178 (67.7%) | 0.005 |

| neutropenia | 29 (4.5%) | 21 (5.5%) | 8 (3.2%) | 0.243 |

| prior surgery (last month) | 367 (57%) | 222 (57.7%) | 145 (56%) | 0.686 |

| total parenteral nutrition | 290 (48.4%) | 162 (47.8%) | 128 (49.2%) | 0.742 |

| prior corticoid therapy | 166 (25.7%) | 114 (29.6%) | 52 (19.9%) | 0.006 |

| Source of candidaemia | ||||

| primary | 275 (43.4%) | 208 (54%) | 67 (27%) | <0.001 |

| catheter related | 253 (39.8%) | 137 (35.6%) | 116 (46.2%) | 0.008 |

| urinary | 47 (7.5%) | 27 (7%) | 20 (8.2%) | 0.646 |

| abdominal | 43 (7%) | 10 (2.7%) | 33 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Severity of infection | ||||

| Pitt score >2 | 178 (29.6%) | 106 (31.4%) | 72 (27.4%) | 0.322 |

| shock at onset | 200 (30.9%) | 104 (27%) | 96 (36.5%) | 0.012 |

| persistent candidaemia | 125 (20.4%) | 73 (19.6%) | 52 (20.6%) | 0.760 |

| Characteristic . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| median age, years (IQR) | 67 (55–76.9) | 67.3 (54.3–76.8) | 67 (56–77) | 0.655 |

| male sex | 375 (58%) | 218 (56.6%) | 157 (59.9%) | 0.418 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| diabetes mellitus | 173 (26.9%) | 94 (24.4%) | 79 (30.5%) | 0.103 |

| chronic kidney failure | 134 (20.9%) | 92 (23.9%) | 42 (16.3%) | 0.023 |

| chronic liver disease | 92 (14.3%) | 67 (17.4%) | 25 (9.7%) | 0.008 |

| chronic lung disease | 118 (18.3%) | 83 (21.6%) | 35 (13.5%) | 0.010 |

| haematological malignancy | 40 (6.2%) | 27 (7%) | 13 (4.9%) | 0.321 |

| solid organ malignancy | 243 (37.6%) | 143 (37.2%) | 100 (38.2%) | 0.869 |

| HSCT | 36 (7%) | 27 (10.5%) | 9 (3.5%) | 0.002 |

| solid organ transplantation | 55 (8.5%) | 32 (8.3%) | 23 (8.9%) | 0.89 |

| HIV infection | 12 (1.9%) | 10 (2.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0.137 |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 465 (71.9%) | 284 (74%) | 181 (68.8%) | 0.156 |

| Risk factors for candidaemia | ||||

| central venous catheter | 477 (73.6%) | 299 (77.7%) | 178 (67.7%) | 0.005 |

| neutropenia | 29 (4.5%) | 21 (5.5%) | 8 (3.2%) | 0.243 |

| prior surgery (last month) | 367 (57%) | 222 (57.7%) | 145 (56%) | 0.686 |

| total parenteral nutrition | 290 (48.4%) | 162 (47.8%) | 128 (49.2%) | 0.742 |

| prior corticoid therapy | 166 (25.7%) | 114 (29.6%) | 52 (19.9%) | 0.006 |

| Source of candidaemia | ||||

| primary | 275 (43.4%) | 208 (54%) | 67 (27%) | <0.001 |

| catheter related | 253 (39.8%) | 137 (35.6%) | 116 (46.2%) | 0.008 |

| urinary | 47 (7.5%) | 27 (7%) | 20 (8.2%) | 0.646 |

| abdominal | 43 (7%) | 10 (2.7%) | 33 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Severity of infection | ||||

| Pitt score >2 | 178 (29.6%) | 106 (31.4%) | 72 (27.4%) | 0.322 |

| shock at onset | 200 (30.9%) | 104 (27%) | 96 (36.5%) | 0.012 |

| persistent candidaemia | 125 (20.4%) | 73 (19.6%) | 52 (20.6%) | 0.760 |

Table 3 details Candida species isolated in the pre-intervention and intervention groups. Candida glabrata was more frequent in the intervention group. There was an outbreak of Candida auris in one hospital during the intervention period. The fluconazole resistance rate was 13% in the pre-intervention group versus 18.4% in the intervention group (P = 0.083).

Candida species isolated and azole susceptibility in pre-intervention and intervention groups

| Species isolated . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 271 (41.8%) | 173 (44.9%) | 98 (37.3%) | 0.062 |

| C. glabrata | 101 (15.6%) | 48 (12.5%) | 53 (20.2%) | 0.011 |

| C. parapsilosis | 135 (20.8%) | 87 (22%) | 48 (18.3%) | 0.201 |

| C. tropicalis | 61 (9.4%) | 37 (9.6%) | 24 (9.1%) | 0.892 |

| C. auris | 28 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (10.6%) | <0.001 |

| C. krusei | 17 (2.6%) | 11 (2.9%) | 6 (2.3%) | 0.804 |

| C. lusitaniae | 6 (0.9%) | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (1.5%) | 0.230 |

| C. guilliermondii | 7 (1.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.251 |

| Others | 24 (3.7%) | 16 (4.2%) | 8 (3%) | 0.530 |

| Mixed candidaemia | 12 (1.9%) | 5 (1.3%) | 7 (2.7%) | 0.242 |

| Fluconazole-resistant strains | 93 (15.1%) | 49 (13%) | 44 (18.4%) | 0.083 |

| Species isolated . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 271 (41.8%) | 173 (44.9%) | 98 (37.3%) | 0.062 |

| C. glabrata | 101 (15.6%) | 48 (12.5%) | 53 (20.2%) | 0.011 |

| C. parapsilosis | 135 (20.8%) | 87 (22%) | 48 (18.3%) | 0.201 |

| C. tropicalis | 61 (9.4%) | 37 (9.6%) | 24 (9.1%) | 0.892 |

| C. auris | 28 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (10.6%) | <0.001 |

| C. krusei | 17 (2.6%) | 11 (2.9%) | 6 (2.3%) | 0.804 |

| C. lusitaniae | 6 (0.9%) | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (1.5%) | 0.230 |

| C. guilliermondii | 7 (1.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.251 |

| Others | 24 (3.7%) | 16 (4.2%) | 8 (3%) | 0.530 |

| Mixed candidaemia | 12 (1.9%) | 5 (1.3%) | 7 (2.7%) | 0.242 |

| Fluconazole-resistant strains | 93 (15.1%) | 49 (13%) | 44 (18.4%) | 0.083 |

Candida species isolated and azole susceptibility in pre-intervention and intervention groups

| Species isolated . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 271 (41.8%) | 173 (44.9%) | 98 (37.3%) | 0.062 |

| C. glabrata | 101 (15.6%) | 48 (12.5%) | 53 (20.2%) | 0.011 |

| C. parapsilosis | 135 (20.8%) | 87 (22%) | 48 (18.3%) | 0.201 |

| C. tropicalis | 61 (9.4%) | 37 (9.6%) | 24 (9.1%) | 0.892 |

| C. auris | 28 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (10.6%) | <0.001 |

| C. krusei | 17 (2.6%) | 11 (2.9%) | 6 (2.3%) | 0.804 |

| C. lusitaniae | 6 (0.9%) | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (1.5%) | 0.230 |

| C. guilliermondii | 7 (1.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.251 |

| Others | 24 (3.7%) | 16 (4.2%) | 8 (3%) | 0.530 |

| Mixed candidaemia | 12 (1.9%) | 5 (1.3%) | 7 (2.7%) | 0.242 |

| Fluconazole-resistant strains | 93 (15.1%) | 49 (13%) | 44 (18.4%) | 0.083 |

| Species isolated . | All cases (n = 648) . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 271 (41.8%) | 173 (44.9%) | 98 (37.3%) | 0.062 |

| C. glabrata | 101 (15.6%) | 48 (12.5%) | 53 (20.2%) | 0.011 |

| C. parapsilosis | 135 (20.8%) | 87 (22%) | 48 (18.3%) | 0.201 |

| C. tropicalis | 61 (9.4%) | 37 (9.6%) | 24 (9.1%) | 0.892 |

| C. auris | 28 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (10.6%) | <0.001 |

| C. krusei | 17 (2.6%) | 11 (2.9%) | 6 (2.3%) | 0.804 |

| C. lusitaniae | 6 (0.9%) | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (1.5%) | 0.230 |

| C. guilliermondii | 7 (1.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.251 |

| Others | 24 (3.7%) | 16 (4.2%) | 8 (3%) | 0.530 |

| Mixed candidaemia | 12 (1.9%) | 5 (1.3%) | 7 (2.7%) | 0.242 |

| Fluconazole-resistant strains | 93 (15.1%) | 49 (13%) | 44 (18.4%) | 0.083 |

Quality of care and outcomes

Table 4 compares the following aspects: crude adherence to the eight QCIs selected; median percentage of improvement; and relative risk of adherence to QCI in the pre-intervention and intervention groups. Adherence to the eight selected QCIs improved across the board during the intervention period.

| QCI . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | Median improvement in percentage of adherence to QCI (IQR) . | Relative risk for adherence to QCI (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early appropriate antifungal therapy | 248 (64.4%) | 203 (81.5%) | 6.9 (4.3–33) | 2.4 (1.7–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock or severely ill patients in ICUa | 47 (45.6%) | 64 (71.1%) | 26.1 (0–52.5) | 2.5 (1.39–4.51) | <0.001 |

| Early source controlb | 165 (54.8%) | 168 (85.7%) | 29.5 (20.2–40.8) | 4.9 (3.1–7.8) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up blood culture | 293 (76.1%) | 220 (87.6%) | 17 (7.4–26.5) | 2.2 (1.4–3.5) | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | 192 (52.5%) | 221 (85.7%) | 38.5 (28.3–62.2) | 5.4 (3.6–8.1) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiography | 319 (84.8%) | 232 (91%) | 9.4 (20.2–40.8) | 1.8 (1.1–3) | 0.023 |

| De-escalation | 254 (69.2%) | 210 (84.3%) | 13.1 (1.6–22.2) | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Adequate length of antifungal treatment | 248 (65.3%) | 237 (96.3%) | 32.1 (23.1–41.9) | 14.02 (6.9–28.2) | <0.001 |

| QCI . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | Median improvement in percentage of adherence to QCI (IQR) . | Relative risk for adherence to QCI (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early appropriate antifungal therapy | 248 (64.4%) | 203 (81.5%) | 6.9 (4.3–33) | 2.4 (1.7–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock or severely ill patients in ICUa | 47 (45.6%) | 64 (71.1%) | 26.1 (0–52.5) | 2.5 (1.39–4.51) | <0.001 |

| Early source controlb | 165 (54.8%) | 168 (85.7%) | 29.5 (20.2–40.8) | 4.9 (3.1–7.8) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up blood culture | 293 (76.1%) | 220 (87.6%) | 17 (7.4–26.5) | 2.2 (1.4–3.5) | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | 192 (52.5%) | 221 (85.7%) | 38.5 (28.3–62.2) | 5.4 (3.6–8.1) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiography | 319 (84.8%) | 232 (91%) | 9.4 (20.2–40.8) | 1.8 (1.1–3) | 0.023 |

| De-escalation | 254 (69.2%) | 210 (84.3%) | 13.1 (1.6–22.2) | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Adequate length of antifungal treatment | 248 (65.3%) | 237 (96.3%) | 32.1 (23.1–41.9) | 14.02 (6.9–28.2) | <0.001 |

193 patients.

477 patients. If we only take into account those with catheter related-candidaemia (253 patients), the early catheter removal rate was 44.2% versus 86.6%, P<0.001.

| QCI . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | Median improvement in percentage of adherence to QCI (IQR) . | Relative risk for adherence to QCI (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early appropriate antifungal therapy | 248 (64.4%) | 203 (81.5%) | 6.9 (4.3–33) | 2.4 (1.7–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock or severely ill patients in ICUa | 47 (45.6%) | 64 (71.1%) | 26.1 (0–52.5) | 2.5 (1.39–4.51) | <0.001 |

| Early source controlb | 165 (54.8%) | 168 (85.7%) | 29.5 (20.2–40.8) | 4.9 (3.1–7.8) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up blood culture | 293 (76.1%) | 220 (87.6%) | 17 (7.4–26.5) | 2.2 (1.4–3.5) | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | 192 (52.5%) | 221 (85.7%) | 38.5 (28.3–62.2) | 5.4 (3.6–8.1) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiography | 319 (84.8%) | 232 (91%) | 9.4 (20.2–40.8) | 1.8 (1.1–3) | 0.023 |

| De-escalation | 254 (69.2%) | 210 (84.3%) | 13.1 (1.6–22.2) | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Adequate length of antifungal treatment | 248 (65.3%) | 237 (96.3%) | 32.1 (23.1–41.9) | 14.02 (6.9–28.2) | <0.001 |

| QCI . | Pre-intervention group (n = 385) . | Intervention group (n = 263) . | Median improvement in percentage of adherence to QCI (IQR) . | Relative risk for adherence to QCI (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early appropriate antifungal therapy | 248 (64.4%) | 203 (81.5%) | 6.9 (4.3–33) | 2.4 (1.7–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Initial treatment with echinocandins if septic shock or severely ill patients in ICUa | 47 (45.6%) | 64 (71.1%) | 26.1 (0–52.5) | 2.5 (1.39–4.51) | <0.001 |

| Early source controlb | 165 (54.8%) | 168 (85.7%) | 29.5 (20.2–40.8) | 4.9 (3.1–7.8) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up blood culture | 293 (76.1%) | 220 (87.6%) | 17 (7.4–26.5) | 2.2 (1.4–3.5) | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmoscopic evaluation | 192 (52.5%) | 221 (85.7%) | 38.5 (28.3–62.2) | 5.4 (3.6–8.1) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiography | 319 (84.8%) | 232 (91%) | 9.4 (20.2–40.8) | 1.8 (1.1–3) | 0.023 |

| De-escalation | 254 (69.2%) | 210 (84.3%) | 13.1 (1.6–22.2) | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) | <0.001 |

| Adequate length of antifungal treatment | 248 (65.3%) | 237 (96.3%) | 32.1 (23.1–41.9) | 14.02 (6.9–28.2) | <0.001 |

193 patients.

477 patients. If we only take into account those with catheter related-candidaemia (253 patients), the early catheter removal rate was 44.2% versus 86.6%, P<0.001.

Crude univariate analysis showed that early [50 patients in the pre-intervention group (13%) versus 19 patients in the intervention group (7.2%); P = 0.02] and overall mortality [109 patients in the pre-intervention group (28.3%) versus 49 patients in the intervention group (18.8%); P = 0.006] were significantly lower in the intervention group. Multivariate analyses to identify independent factors related to early and overall mortality are detailed in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. The clinical intervention was independently associated with decreased early (OR 0.46; 95% CI 0.23–0.89; P = 0.022) and overall (OR 0.61; 95% CI 0.4–0.94; P = 0.023) mortality after controlling for potential confounders. The goodness-of-fit of the models was assessed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (P = 0.228 and P = 0.734, respectively). The discriminatory power of the model, as evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, was 0.769 (95% CI 0.71–0.82) and 0.747 (95% CI 0.703–0.791), showing a good ability to predict early and overall mortality, respectively.

Factors associated with early mortality: uni- and multivariate regression analyses

| . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.84 | 1.38–5.87 | 0.003 | 2.63 | 1.23–5.61 | 0.012 |

| Neutropenia | 3.49 | 1.48–8.21 | 0.008 | 3.47 | 1.38–8.72 | 0.008 |

| Septic shock | 2.58 | 1.56–4.28 | <0.001 | 2.96 | 1.69–5.21 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 3.36 | 1.43–7.87 | 0.009 | 2.61 | 1.02–6.68 | 0.046 |

| Primary source | 1.82 | 1.10–3.02 | 0.021 | 2.47 | 1.33–4.57 | 0.004 |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.38 | 0.21–0.69 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Abdominal source | 2.66 | 1.25–5.65 | 0.019 | 5.71 | 2.25–14.49 | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 0.52 | 0.30–0.91 | 0.020 | 0.46 | 0.23–0.89 | 0.022 |

| . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.84 | 1.38–5.87 | 0.003 | 2.63 | 1.23–5.61 | 0.012 |

| Neutropenia | 3.49 | 1.48–8.21 | 0.008 | 3.47 | 1.38–8.72 | 0.008 |

| Septic shock | 2.58 | 1.56–4.28 | <0.001 | 2.96 | 1.69–5.21 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 3.36 | 1.43–7.87 | 0.009 | 2.61 | 1.02–6.68 | 0.046 |

| Primary source | 1.82 | 1.10–3.02 | 0.021 | 2.47 | 1.33–4.57 | 0.004 |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.38 | 0.21–0.69 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Abdominal source | 2.66 | 1.25–5.65 | 0.019 | 5.71 | 2.25–14.49 | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 0.52 | 0.30–0.91 | 0.020 | 0.46 | 0.23–0.89 | 0.022 |

Factors associated with early mortality: uni- and multivariate regression analyses

| . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.84 | 1.38–5.87 | 0.003 | 2.63 | 1.23–5.61 | 0.012 |

| Neutropenia | 3.49 | 1.48–8.21 | 0.008 | 3.47 | 1.38–8.72 | 0.008 |

| Septic shock | 2.58 | 1.56–4.28 | <0.001 | 2.96 | 1.69–5.21 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 3.36 | 1.43–7.87 | 0.009 | 2.61 | 1.02–6.68 | 0.046 |

| Primary source | 1.82 | 1.10–3.02 | 0.021 | 2.47 | 1.33–4.57 | 0.004 |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.38 | 0.21–0.69 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Abdominal source | 2.66 | 1.25–5.65 | 0.019 | 5.71 | 2.25–14.49 | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 0.52 | 0.30–0.91 | 0.020 | 0.46 | 0.23–0.89 | 0.022 |

| . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.84 | 1.38–5.87 | 0.003 | 2.63 | 1.23–5.61 | 0.012 |

| Neutropenia | 3.49 | 1.48–8.21 | 0.008 | 3.47 | 1.38–8.72 | 0.008 |

| Septic shock | 2.58 | 1.56–4.28 | <0.001 | 2.96 | 1.69–5.21 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 3.36 | 1.43–7.87 | 0.009 | 2.61 | 1.02–6.68 | 0.046 |

| Primary source | 1.82 | 1.10–3.02 | 0.021 | 2.47 | 1.33–4.57 | 0.004 |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.38 | 0.21–0.69 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Abdominal source | 2.66 | 1.25–5.65 | 0.019 | 5.71 | 2.25–14.49 | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 0.52 | 0.30–0.91 | 0.020 | 0.46 | 0.23–0.89 | 0.022 |

Factors associated with overall mortality: uni- and multivariate regression analyses

| Variable . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.15 | 1.37–3.37 | 0.001 | 2.16 | 1.32–3.53 | 0.002 |

| Neutropenia | 2.64 | 1.24–5.61 | 0.009 | 2.41 | 1.07–5.46 | 0.035 |

| Septic shock | 2.53 | 1.74–3.67 | <0.001 | 2.61 | 1.72–4.0 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 5.10 | 2.40–10.86 | <0.001 | 5.26 | 2.19–12.64 | <0.001 |

| Primary source | 1.99 | 1.34–2.87 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.41 | 0.27–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.24–0.58 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal source | 2.25 | 1.19–4.22 | 0.010 | – | – | – |

| Urinary source | 0.42 | 0.18–1.016 | 0.053 | 0.20 | 0.07–0.56 | 0.002 |

| Intervention | 0.59 | 0.40–0.86 | 0.006 | 0.61 | 0.4–0.94 | 0.023 |

| Variable . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.15 | 1.37–3.37 | 0.001 | 2.16 | 1.32–3.53 | 0.002 |

| Neutropenia | 2.64 | 1.24–5.61 | 0.009 | 2.41 | 1.07–5.46 | 0.035 |

| Septic shock | 2.53 | 1.74–3.67 | <0.001 | 2.61 | 1.72–4.0 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 5.10 | 2.40–10.86 | <0.001 | 5.26 | 2.19–12.64 | <0.001 |

| Primary source | 1.99 | 1.34–2.87 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.41 | 0.27–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.24–0.58 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal source | 2.25 | 1.19–4.22 | 0.010 | – | – | – |

| Urinary source | 0.42 | 0.18–1.016 | 0.053 | 0.20 | 0.07–0.56 | 0.002 |

| Intervention | 0.59 | 0.40–0.86 | 0.006 | 0.61 | 0.4–0.94 | 0.023 |

Factors associated with overall mortality: uni- and multivariate regression analyses

| Variable . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.15 | 1.37–3.37 | 0.001 | 2.16 | 1.32–3.53 | 0.002 |

| Neutropenia | 2.64 | 1.24–5.61 | 0.009 | 2.41 | 1.07–5.46 | 0.035 |

| Septic shock | 2.53 | 1.74–3.67 | <0.001 | 2.61 | 1.72–4.0 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 5.10 | 2.40–10.86 | <0.001 | 5.26 | 2.19–12.64 | <0.001 |

| Primary source | 1.99 | 1.34–2.87 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.41 | 0.27–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.24–0.58 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal source | 2.25 | 1.19–4.22 | 0.010 | – | – | – |

| Urinary source | 0.42 | 0.18–1.016 | 0.053 | 0.20 | 0.07–0.56 | 0.002 |

| Intervention | 0.59 | 0.40–0.86 | 0.006 | 0.61 | 0.4–0.94 | 0.023 |

| Variable . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate regression analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | RR . | 95% CI . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Charlson index ≥2 | 2.15 | 1.37–3.37 | 0.001 | 2.16 | 1.32–3.53 | 0.002 |

| Neutropenia | 2.64 | 1.24–5.61 | 0.009 | 2.41 | 1.07–5.46 | 0.035 |

| Septic shock | 2.53 | 1.74–3.67 | <0.001 | 2.61 | 1.72–4.0 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis requirement due to candidaemia | 5.10 | 2.40–10.86 | <0.001 | 5.26 | 2.19–12.64 | <0.001 |

| Primary source | 1.99 | 1.34–2.87 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Catheter-related candidaemia | 0.41 | 0.27–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.24–0.58 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal source | 2.25 | 1.19–4.22 | 0.010 | – | – | – |

| Urinary source | 0.42 | 0.18–1.016 | 0.053 | 0.20 | 0.07–0.56 | 0.002 |

| Intervention | 0.59 | 0.40–0.86 | 0.006 | 0.61 | 0.4–0.94 | 0.023 |

Discussion

Our main finding was that implementing a structured, evidence-based intervention bundle significantly improved patient care in patients with candidaemia, especially as gauged by the adherence to QCIs. It was significantly associated with a reduction in early and overall mortality.

The bundle of interventions proposed combines a series of recommendations included in management guidelines with varying strength levels. One crucial aspect concerns the initial choice of antifungal treatment. In order to improve the rates of adequate early antifungal therapy, we made some suggestions. First, physicians were encouraged to follow a simple bed score tool, the Flu-NS score, which has proven useful in predicting azole-resistant isolates.16,17 Moreover, a change in drug class in patients with breakthrough candidaemia (given the frequency of isolates that are resistant to prior treatments) was included in the bundle. A particular situation occurs in which the fungicidal activity of echinocandin drugs offers a plausible advantage over azole treatment in critically ill patients.8,18,19 Another cornerstone in the optimal management of candidiasis is measures to control the source of the infection. The bundle includes recommendations on early removal of the CVC, particularly for patients with a catheter source, as well as early drainage of abscesses or obstructive alterations in the urinary tract, which are sources of candidaemia.9,11

After an early optimal therapeutic approach, our bundle focuses on identifying complicated candidaemia. Follow-up blood cultures, ophthalmoscopies or echocardiograms were recommended, in order to quantify the real burden of invasive candidiasis and consequently invoke an optimal length of therapy.12,20,21 Implementation of our bundle increased the number of these tests that were performed. Lastly, our bundle also provides the means to implement measures to ensure adequacy of treatment, such as optimal de-escalation, proposing antifungal stewardship according to susceptibility data, and adequate length of antifungal treatment strictly following literature and guideline recommendations.22–24 It is plausible that close follow-up by an infectious disease specialist was crucial in the better outcomes of these patients, as has been demonstrated in other difficult-to-treat infections.25 Given the high comorbidity burden usually found in patients with Candida bloodstream infections, the analysis of potentially modifiable factors associated with mortality in these patients is extremely difficult. However, it is certainly reasonable to assume that a rigorous application of a bundle of evidence-based measures aimed at optimizing management would be associated with improvements in clinical outcomes. Other authors have previously analysed the usefulness of care bundles in candidaemia.22,26,27 The vast majority of these, however, were single-centre studies with small sample sizes. All but one found a positive impact of the bundle intervention in terms of greater compliance with recommendations in the post-intervention period. Nonetheless, a significantly favourable impact on clinical outcomes was not demonstrated. Finally, the most relevant work that has analysed the application of care bundles in candidaemia was that overseen by Takesue et al.,28 in a nationwide multicentre study in Japan involving information from 11 geographical regions throughout the country. Data from 608 patients were analysed in order to assess whether compliance with their bundle improved mortality. Despite a relatively low compliance (compliance rate for achieving all elements was 6.9%, and increased to 21.4% when it was analysed excluding oral switch from the bundle), a significant difference in clinical success between patients with and without compliance was found (92.9% versus 75.8%; P < 0.01). When step-down oral therapy was excluded from the elements of compliance, compliance with the bundles was revealed to be an independent predictor of clinical success (OR 4.42; 95% CI 2.05–9.52) and mortality (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.13–0.57).28

In our view, the present study provides valuable information for improving patients’ quality of care. In an era in which high quality of care is crucial to health planners and managers, having an objective bundle, which can be easily introduced as a critical pathway, minimizes the chance of medical error and allows it to be an effective clinimetric tool. This study validates our bundle as a quality-of-care measure to improve patients’ outcomes.

Our study has important strengths: multicentre nature; prospective design; the use of evidence-based QCIs; a large number of candidaemia episodes analysed; the easy replicability of our intervention; and simplicity of incorporating the bundle in clinical practice. However, the main limitation is that our study is not a randomized controlled trial. The differences in baseline characteristics between the groups is another limitation of this study. Taking into account that these indicators of clinical management have proven effective on an individual basis, it most likely would not have been ethical to set out a trial with such an objective. Another limitation is the outbreak of C. auris in one hospital, which occurred during the intervention period. Even though this could have affected the results, we believe that the C. auris infection would have been associated with a deeper complexity found within the cohort of patients from the intervention group. Quasi-experimental studies have inherent limitations such us unmeasured factors influencing results. In an attempt to limit the effects of such potential confounding factors, we employed multivariate analysis.

In conclusion, this multicentre study found that the implementation of a structured evidence-based intervention bundle significantly improved patient care and was ultimately associated with a reduction in early and overall mortality. Institutions are recommended to embrace such strategies that aim to increase guideline adherence and as a result, improve outcomes of patients affected by the deadly infection known as candidaemia.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anthony Armenta for his contribution in correcting the English language/syntax of this article.

Members of the Spanish CANDI-Bundle Group

J.A. Martínez, L. Morata, O. Rodríguez-Nuñez, M.A. Guerrero, J. Ayats, I. Grau, E. Calabuig, I. Castro, S. Cuéllar, P. Martín-Dávila, E. Gómez-García de la Pedrosa, A. Pérez-Ayala, I. Losada, M.D. Navarro, A.I. Suarez, M.T. Martin-Gomez, R. Rodríguez-Alvarez, L. López-Soira, E. Bouza, J. Guinea and C. Martín.

Funding

This study was funded by a research grant from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS PI15/00744). This study is also co-financed by the European Development Regional Fund ‘A way to achieve Europe’ ERDF, Spanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD06/0008). The funding institutions had no role in the design or performance of the research. C.G.-V. is a recipient of an INTENSIFICACIÓ Grant from the ‘Strategic plan for research and innovation in health-PERIS 2016–2020’ and forms part of the FungiCLINIC Research group (AGAUR-Project 2017SGR1432 of the Catalan Health Agency).

Transparency declarations

M.S. has received honoraria for participating in meetings, forums and consultancies, as well as for having attended conferences for MSD, Pfizer, Janssen, Angelini, ERN, Gilead and Astellas Ph. He has also received grants and scholarships for research and teaching, which were administered through La Fe Sanitary Research Institute (IIS-LA FE) and companies such as ViiV, Janssen, MSD. M.F.-R. has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Science, Astellas and Pfizer. L.E.L.-C. has served as speaker for MSD and Angellini, has received research support from Novartis and served as a trainer for MSD. P.M. is a consultant and/or speaker for Astellas, Gilead, MSD, Novartis and Pfizer and T2 Biosystems. J.F. has been advisor/consultant and has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer and Astellas Pharma. J.M.A. has received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized on behalf of Pfizer, Astellas, MSD, Angelini and has sat on advisory boards for antifungal agents on behalf of Pfizer, Astellas, MSD, Angelini and Gilead Science. B.A. has received grant support from Gilead Sciences, Pfizer and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and he has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Astellas, Angellini and Novartis. J.C. has received honoraria for lectures from Gilead and MSD; C.G.-V. has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Science, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Janssen, as well as a grant from Gilead Science. All other authors: none to declare.

References

Author notes

Celia Cardozo and Guillermo Cuervo made an equal contribution to the paper.

Members are listed in the Acknowledgements section.