-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Steven J Nigro, Melissa H Brown, Ruth M Hall, AbGRI1-5, a novel AbGRI1 variant in an Acinetobacter baumannii GC2 isolate from Adelaide, Australia, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 74, Issue 3, March 2019, Pages 821–823, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky459

Close - Share Icon Share

Sir,

Isolates belonging to global clone 2 (GC2) are the most commonly seen extensively antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii observed worldwide and almost all sequenced GC2 isolates harbour at least two resistance islands in their chromosome.1–3 AbGRI1, which interrupts the chromosomal comM gene, was the first of these islands to be characterized in three distinct variant forms. These variants were originally known as Tn6166,4 Tn61675 and RIMDR-TJ,2 but have since been renamed AbGRI1-1, AbGRI1-2 and AbGRI1-3, respectively. AbGRI1 usually contains some or all of the sul2, tetA(B), strB and strA genes, which confer resistance to sulphonamides, tetracycline and minocycline, and streptomycin, respectively.2–5 Although AbGRI1 variants are in the same location as AbaR islands, which are found in most GC1 isolates, they have a different structure. The origin of the AbGRI1 type was recently found and the progenitor of the known variants, which does not include tetA(B), was named AbGRI1-0 (Figure 1a).6

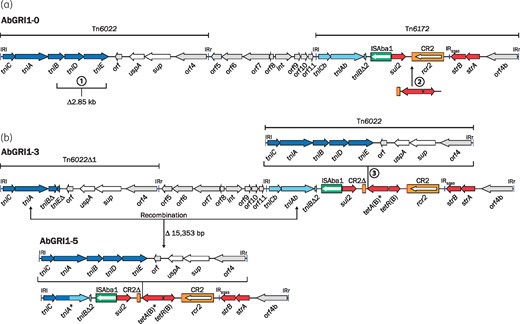

Structures of AbGRI1. (a) The hypothetical ancestor AbGRI1-0 and (b) the recombination between tniA and tniAb in AbGRI1-3 that results in AbGRI1-5. The orientation and extent of genes are represented by coloured arrows and inverted repeats are shown as blue vertical lines. Dark blue arrows are transfer genes of Tn6022, while the light blue arrows are the related transfer genes of Tn6172. Red arrows represent resistance genes and grey arrows are ORFs of unknown function. The green box represents ISAba1 and the orange box with a red bar indicating the ori end is CR2. The extents of named transposon regions of AbGRI1 are indicated above. The circled numbers 1, 2 and 3 represent the key variations of AbGRI1 that are described in the text. In (b), the extent of the recombination resulting in AbGRI1-5 is shown with the double-ended arrowed line. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Two variations relative to AbGRI1-0, namely a 2.85 kb deletion in Tn6022 and the addition of a 2580 bp fragment that includes tet(B), are found in AbGRI1-2 and AbGRI1-3, which are commonly observed in recent isolates collected after 2000.2,3,5–8 A third variation arises from the incorporation of an additional Tn6022 near the end of the tetA(B) gene. These three variations (marked 1, 2 and 3 in Figure 1) were first seen together in AbGRI1-3 in the Chinese isolate MDR-TJ (Figure 1b).2 The incoming Tn6022 interrupts the tetA(B) gene close to the C-terminus, but an in-frame stop codon within the IRr of Tn6022 facilitates termination of the protein. However, this does not appear to have affected the activity of the tetracycline efflux pump, as isolates with this configuration are still resistant to tetracycline and minocycline.4 This tetA(B) variation, tentatively named tetA(B)*, was seen previously in AbGRI1-1 of the 1982 isolate A320 from the Netherlands,4 suggesting AbGRI1-1 is derived from AbGRI1-3.

Isolate K16 is a member of GC2 that was collected at Royal Adelaide Hospital in 2004 and was previously referred to as 4117201.9 Using a disc diffusion assay, as described previously,3 it was found to be resistant to ampicillin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, streptomycin, spectinomycin, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, florfenicol, nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin, as well as the aminoglycosides kanamycin, neomycin and gentamicin. The genome of K16 was sequenced as part of a larger sequencing project (PRJEB2801, SAMEA1876501) using Illumina HiSeq and assembled using Velvet 1.2.03.10,11 MLST (http://pubmlst.org/abaumannii) confirmed it was a GC2 isolate, as K16 was ST2 (Institut Pasteur scheme) and ST208 (Oxford scheme).

K16 harbours an ISAba1 upstream of the ampC-2 allele, responsible for resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. It also has single base changes in gyrA and parC that result in Ser81Leu and Ser84Leu substitutions in GyrA and ParC, respectively, which are characteristic of resistance to quinolones and fluoroquinolones. In addition, it has blaTEM and the aminoglycoside resistance genes aphA1, aadA1 and aacC1 in the AbGRI2-1 form12 of the second resistance island, at its characteristic location in the chromosome.

The typical AbGRI1 genes sul2, strA, strB and tetA(B) were all present in the K16 genome. However, tetA(B) was interrupted near the C-terminus, at the characteristic position of Tn6022 in AbGRI1-3. Hence, AbGRI1-3 was used as a scaffold to identify fragments of the AbGRI1 variant in comM of K16 and assemble them. Primers in sul2 and uspA, found on separate contigs, produced an 8.4 kb amplicon and sequencing of this product confirmed that K16 harboured a Tn6022 interrupting tetA(B). However, the overall structure seen here was shorter than AbGRI1-3 and the region at one end is a fusion of Tn6022Δ1 and Tn6172 with a hybrid tniA gene (tniA* in Figure 1b), which contains 768 bp of tniA from Tn6022 at the 5′-end (dark blue in Figure 1b) and 1143 bp of tniAb from Tn6172 at the 3′-end (light blue in Figure 1b). This configuration has arisen from AbGRI1-3 via homologous recombination between tniA and tniAb, which share 94.4% DNA identity, removing 15353 bp of AbGRI1-3 in the process (Figure 1). The 23302 bp variant in K16 was named AbGRI1-5.

Searches of the GenBank non-redundant database found that AbGRI1-5 is unique. Only a single genome released recently had an island identical to AbGRI1-5, though it had not been described in detail.13 The isolate, AYP-A2, is a GC2 isolate collected at a Melbourne hospital in 2013 and is a carbapenem-resistant representative of a series of isolates collected from a single patient and three other patients from the same ward.13 Hence, a GC2 lineage carrying AbGRI1-5 may be unique to Australia.

In contrast to AbGRI1-5, which can be derived from AbGRI1-3 via a single recombination event (Figure 1b), the AbGRI1-2 variant, which is only seen in ST208 isolates from Sydney, Brisbane and Canberra,3 does not appear to be directly derived from AbGRI1-3. Hence, AbGRI1-2 and AbGRI1-5 may have followed different evolutionary paths from their common ancestor. Further work will be needed to establish the evolutionary relationship between these two GC2 lineages found in Australia.

The sequence of AbGRI1-5 was deposited in GenBank under accession number MH500799.

Funding

This work was supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grants 1026189 and 1043830. S. J. N. was supported by Australian NHMRC project grant 1043830.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.