-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dafna Ben Yaakov, Yana Shadkchan, Nathaniel Albert, Dimitrios P. Kontoyiannis, Nir Osherov, The quinoline bromoquinol exhibits broad-spectrum antifungal activity and induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in Aspergillus fumigatus, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 72, Issue 8, August 2017, Pages 2263–2272, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx117

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objectives: Over the last 30 years, the number of invasive fungal infections among immunosuppressed patients has increased significantly, while the number of effective systemic antifungal drugs remains low. The aim of this study was to identify and characterize antifungal compounds that inhibit fungus-specific metabolic pathways not conserved in humans.

Methods: We screened a diverse compound library for antifungal activity in the pathogenic mould Aspergillus fumigatus. We determined the in vitro activity of bromoquinol by MIC determination against a panel of fungi, bacteria and cell lines. The mode of action of bromoquinol was determined by screening an Aspergillus nidulans overexpression genomic library for resistance-conferring genes and by RNAseq analysis in A. fumigatus. In vivo efficacy was tested in Galleria mellonella and murine models of A. fumigatus infection.

Results: Screening of a diverse chemical library identified three compounds interfering with fungal iron utilization. The most potent, bromoquinol, shows potent wide-spectrum antifungal activity that was blocked in the presence of exogenous iron. Mode-of-action analysis revealed that overexpression of the dba secondary metabolite cluster gene dbaD, encoding a metabolite transporter, confers bromoquinol resistance in A. nidulans, possibly by efflux. RNAseq analysis and subsequent experimental validation revealed that bromoquinol induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in A. fumigatus. Bromoquinol significantly reduced mortality rates of G. mellonella infected with A. fumigatus, but was ineffective in a murine model of infection.

Conclusions: Bromoquinol is a promising antifungal candidate with a unique mode of action. Its activity is potentiated by iron starvation, as occurs during in vivo growth.

Introduction

The incidence of life-threatening, invasive fungal infections has risen significantly during the past 30 years.1–3 Most fungal infections are caused by species of Cryptococcus, Candida and Aspergillus.4 It is estimated that invasive aspergillosis and candidiasis affect between 10% and 25% of all leukaemic and bone marrow transplant patients, with an alarmingly high mortality rate of ∼50%.5,6 However, despite the growing needs, treatments for invasive fungal infections remain unsatisfactory, with existing classes of antifungals showing toxicity, narrow specificity, increasing resistance or limited formulation.7 Therefore, there is growing urgency to develop novel antifungals that inhibit fungus-specific targets.

We performed a novel screen of 40 000 drug-like molecules from diverse chemical compound libraries, to identify antifungal compounds that inhibit specific fungal pathways not found in humans. In particular, iron8 and zinc9 uptake, aromatic amino acid biosynthesis10 and vitamin para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA),11 riboflavin12 and pyridoxine13 biosynthesis pathways in fungi are of interest in antifungal drug discovery, as these pathways are not evolutionarily conserved in humans. We based our screen on the rationale that hit compounds inhibiting these pathways would be outcompeted and lose their activity upon supplementation with excess metal/aromatic amino acids/vitamins. We identified four compounds that lost all antifungal activity upon addition of excess iron or zinc, two compounds whose activity was eliminated by addition of riboflavin and one by addition of PABA. We focused on the most potent of these seven compounds, the quinoline bromoquinol, whose activity was blocked by iron, copper or zinc supplementation, suggesting that it interferes with the utilization of these essential metals. In this work, we describe the antifungal activity, selectivity, mode of action and in vivo activity of bromoquinol.

Materials and methods

Strains and media

The strains used in this study are detailed in Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). Moulds were grown in YAG yeast extract agar glucose medium or in defined minimal medium (MM) containing 70 mM NaNO3, 1% (w/v) glucose, 12 mM potassium phosphate pH 6.8, 4 mM MgSO4 and 7 mM KCl as previously described.14 Yeast was grown in YPD yeast peptone dextrose-rich medium and bacteria in LB broth.14

Screen for antifungal compounds

Aspergillus fumigatus CEA10 was grown in 96-well plates in a volume of 100 μL of ΔMM [MM without Fe3+, Zn2+, PABA, pyridoxine, riboflavin and aromatic amino acids tryptophan (Trp), phenylalanine (Phe) and tyrosine (Tyr)] containing 5000 conidia. Each well was supplemented with 25 μM of compound from a chemical compound library ChemDiv Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), TimeTec Chemicals (Hyderabad, India) and Asinex Ltd (Moscow, Russia) of 40 000 compounds. MICs were determined after 48 h of incubation at 37°C, relative to the untreated control.

Next, each ‘hit’ was tested against a panel of 10 wells each containing a different additive: 100 μM Fe3+, 100 μM Zn2+, 500 μM PABA, 500 μM pyridoxine, 500 μM riboflavin, aromatic amino acids (0.01 mM Trp, 0.8 mM Tyr, 0.5 mM Phe), RPMI-MOPS medium lacking Fe3+, Zn2+, PABA, pyridoxine and riboflavin, or YAG. Compounds whose inhibitory activity was abolished upon addition of one of the additives mentioned above (‘putative pathway inhibitors’) were chosen for further evaluation.

Pan-fungal and bacterial screen

The fungal strains listed in Table S1 were tested for susceptibility according to CLSI standard M27-A3 or M38-A2 protocols.15,16 Bacterial strains (1.2 × 104 cfu/well) were grown in LB broth and MICs were determined after 48 h at 37°C at OD600.

Cell culture

Hit compounds were tested for toxicity towards mammalian cells using the human lung epithelial cell line A549 (ATCC CLL 185) and NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblasts (ATCC CRL-1658) as described previously.14 The XTT assay kit (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) measured cell viability.

Apoptosis assays and staining procedures

Fungal oxidative stress was detected by microscopy with the fluorescent dye dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Abcam, San Francisco, CA, USA). For assessment of chromatin condensation by bromoquinol, nuclei were stained with DAPI. DNA-strand breaks were detected by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labelling (TUNEL). Af293 protoplasts were prepared according to Jadoun et al.17 Protoplasts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution and then incubated with permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium citrate) for 2 min on ice. Then, protoplasts were incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture for 60 min at 37°C in the dark, according to the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit, Fluorescein (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). Microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axio imager M1 fluorescence microscope. Images were captured with a Zeiss AxioCam MRm camera.

Screening an Aspergillus nidulans overexpression genomic library for resistance-conferring plasmids

A library of A. nidulans transformants containing a genomic library cloned into the multicopy non-integrating vector pRG3-AMA118,19 was screened for resistant strains. Transformation was undertaken as described previously.19

RNAseq and RT-qPCR analysis

A detailed description of the RNAseq and RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis is provided in the Supplementary data. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S2.

In vivo antifungal activity: Galleria mellonella model

Larvae were infected as previously described.14 At 3 h post-infection, larvae were injected with 10 μL of saline containing bromoquinol. Larval survival was measured daily for up to 7 days post-treatment. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

In vivo toxicity and antifungal activity: murine model

Female ICR mice (6 weeks old) were immunocompromised with cortisone acetate and infected intranasally with A. fumigatus Af293 conidia as previously described.20 Mice were treated by intraperitoneal injection 2 h post-inoculation and then once a day for two consecutive days. Viability was assessed for 2 weeks. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results. Experiments were ethically approved by the Ministry of Health Animal Welfare Committee, Israel.

Results

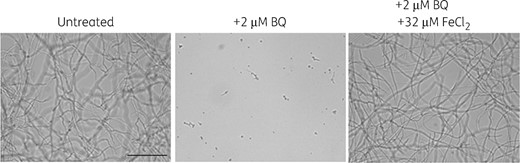

To identify antifungal compounds, we screened 40 000 drug-like molecules from diverse chemical compound libraries of small molecular weight compounds. Each compound (at a concentration of 25 μM) was tested for antifungal activity against a patient isolate of A. fumigatus (CEA10), in a 96-well based liquid assay in ΔMM for 48 h of incubation at 37°C. ΔMM is defined as MM lacking supplementation with Fe3+, Zn2+, PABA, pyridoxine, riboflavin and aromatic amino acids (Trp, Tyr, Phe). Fungal growth on this medium appeared phenotypically normal and growth was reduced by only 20% compared with that of standard supplemented MM as assessed by dry weight of the lyophilized mycelium suggesting they contain traces of Fe3+ and Zn2+ capable of supporting growth. The wells were screened by an inverted light microscope. We identified 237 compounds that completely inhibited germination (MIC ≤25 μM) and selected them for further analysis. We added Fe3+, Zn2+, PABA, pyridoxine, riboflavin or the aromatic amino acids (Trp, Tyr, Phe) to A. fumigatus in the presence of each of the 237 inhibitory compounds at 25 μM. We identified seven inhibitors for which addition of iron (bromoquinol, C11–375, B11–375, D2–431), PABA (D2–77) or riboflavin (G8–58, D4–65) completely reversed inhibition (Table 1 and Figure S1 for chemical structures). Of these seven inhibitors we chose to focus on the quinoline bromoquinol, because of its low MIC (1 μM) in both ΔMM and RPMI-MOPS without Fe3+, Zn2+, PABA, pyroxidine and riboflavin, its clearly defined abolishment of activity in the presence of Fe3+ to the medium (Figure 1) and its non-toxicity towards cells in culture at these concentrations (Table 2).

Antifungal activity of bromoquinol is abolished by iron. A. fumigatus conidia were grown for 24 h at 37 °C in MM lacking iron. Addition of 2 μM bromoquinol completely inhibited fungal growth. Supplementation with 32 μM FeCl2 blocked the antifungal activity of bromoquinol. BQ, bromoquinol.

| Activity blocked by . | ΔMM . | +Fe3+ 100 μM . | +Zn2+ 100 μM . | +PABA 50 μM . | +Pyroxidine 50 μM . | +Riboflavin 50 μM . | +Aromatic amino acidsa . | ΔRPMI-MOPSb . | YAGc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | |||||||||

| bromoquinol | 1 | >25 | >25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | >25 |

| C11-375 | 6.25 | >25 | >25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | >25 |

| B11-375 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| D2-431 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| PABA | |||||||||

| D2-77 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| Riboflavin | |||||||||

| G8-59 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| D4-65 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| Activity blocked by . | ΔMM . | +Fe3+ 100 μM . | +Zn2+ 100 μM . | +PABA 50 μM . | +Pyroxidine 50 μM . | +Riboflavin 50 μM . | +Aromatic amino acidsa . | ΔRPMI-MOPSb . | YAGc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | |||||||||

| bromoquinol | 1 | >25 | >25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | >25 |

| C11-375 | 6.25 | >25 | >25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | >25 |

| B11-375 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| D2-431 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| PABA | |||||||||

| D2-77 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| Riboflavin | |||||||||

| G8-59 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| D4-65 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

Trp (0.01 mM), Tyr (0.8 mM), Phe (0.5 mM).

RPMI-MOPS without Fe3+, Zn2+, PABA, pyroxidine and riboflavin.

YAG = rich fungal medium.

| Activity blocked by . | ΔMM . | +Fe3+ 100 μM . | +Zn2+ 100 μM . | +PABA 50 μM . | +Pyroxidine 50 μM . | +Riboflavin 50 μM . | +Aromatic amino acidsa . | ΔRPMI-MOPSb . | YAGc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | |||||||||

| bromoquinol | 1 | >25 | >25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | >25 |

| C11-375 | 6.25 | >25 | >25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | >25 |

| B11-375 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| D2-431 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| PABA | |||||||||

| D2-77 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| Riboflavin | |||||||||

| G8-59 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| D4-65 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| Activity blocked by . | ΔMM . | +Fe3+ 100 μM . | +Zn2+ 100 μM . | +PABA 50 μM . | +Pyroxidine 50 μM . | +Riboflavin 50 μM . | +Aromatic amino acidsa . | ΔRPMI-MOPSb . | YAGc . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | |||||||||

| bromoquinol | 1 | >25 | >25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | >25 |

| C11-375 | 6.25 | >25 | >25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | >25 |

| B11-375 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| D2-431 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

| PABA | |||||||||

| D2-77 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| Riboflavin | |||||||||

| G8-59 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| D4-65 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | >25 | 25 | 25 | >25 |

Trp (0.01 mM), Tyr (0.8 mM), Phe (0.5 mM).

RPMI-MOPS without Fe3+, Zn2+, PABA, pyroxidine and riboflavin.

YAG = rich fungal medium.

MICs of bromoquinol for pathogenic fungal strains, bacteria and mammalian cell lines

| Species (no. of strains tested) . | MICa (μM) . |

|---|---|

| A. fumigatus (12) | 0.06–1 |

| Aspergillus flavus (7) | 1–2 |

| Aspergillus niger (5) | 0.5–1 |

| Aspergillus terreus (5) | 2–4 |

| Rhizopus oryzae (6) | 16 to >32 |

| Candida glabrata (3) | 2 |

| Candida tropicalis (1) | 2 |

| Candida krusei (5) | 2–4 |

| C. albicans (4) | 1–2 |

| Candida parapsilosis (5) | 1–4 |

| Candida rugosa (2) | 2–4 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2) | 1–2 |

| Escherichia coli (1) | 25 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (1) | 12.5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (1) | 25 |

| Bacillus cereus (1) | 12.5 |

| A549 | >25 (10%)b |

| NIH-3T3 | >25 (20%)b |

| Species (no. of strains tested) . | MICa (μM) . |

|---|---|

| A. fumigatus (12) | 0.06–1 |

| Aspergillus flavus (7) | 1–2 |

| Aspergillus niger (5) | 0.5–1 |

| Aspergillus terreus (5) | 2–4 |

| Rhizopus oryzae (6) | 16 to >32 |

| Candida glabrata (3) | 2 |

| Candida tropicalis (1) | 2 |

| Candida krusei (5) | 2–4 |

| C. albicans (4) | 1–2 |

| Candida parapsilosis (5) | 1–4 |

| Candida rugosa (2) | 2–4 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2) | 1–2 |

| Escherichia coli (1) | 25 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (1) | 12.5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (1) | 25 |

| Bacillus cereus (1) | 12.5 |

| A549 | >25 (10%)b |

| NIH-3T3 | >25 (20%)b |

MIC = the lowest drug concentration completely to arrest germination and growth after 48 h at 37 °C. Fungal strains were grown in RPMI-MOPS (moulds) or in YPD (yeast), mammalian cell lines were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and bacteria were grown in LB broth.

MIC (cell culture) = % growth inhibition at 25 μM bromoquinol, as measured by the XTT assay.

MICs of bromoquinol for pathogenic fungal strains, bacteria and mammalian cell lines

| Species (no. of strains tested) . | MICa (μM) . |

|---|---|

| A. fumigatus (12) | 0.06–1 |

| Aspergillus flavus (7) | 1–2 |

| Aspergillus niger (5) | 0.5–1 |

| Aspergillus terreus (5) | 2–4 |

| Rhizopus oryzae (6) | 16 to >32 |

| Candida glabrata (3) | 2 |

| Candida tropicalis (1) | 2 |

| Candida krusei (5) | 2–4 |

| C. albicans (4) | 1–2 |

| Candida parapsilosis (5) | 1–4 |

| Candida rugosa (2) | 2–4 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2) | 1–2 |

| Escherichia coli (1) | 25 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (1) | 12.5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (1) | 25 |

| Bacillus cereus (1) | 12.5 |

| A549 | >25 (10%)b |

| NIH-3T3 | >25 (20%)b |

| Species (no. of strains tested) . | MICa (μM) . |

|---|---|

| A. fumigatus (12) | 0.06–1 |

| Aspergillus flavus (7) | 1–2 |

| Aspergillus niger (5) | 0.5–1 |

| Aspergillus terreus (5) | 2–4 |

| Rhizopus oryzae (6) | 16 to >32 |

| Candida glabrata (3) | 2 |

| Candida tropicalis (1) | 2 |

| Candida krusei (5) | 2–4 |

| C. albicans (4) | 1–2 |

| Candida parapsilosis (5) | 1–4 |

| Candida rugosa (2) | 2–4 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2) | 1–2 |

| Escherichia coli (1) | 25 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (1) | 12.5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (1) | 25 |

| Bacillus cereus (1) | 12.5 |

| A549 | >25 (10%)b |

| NIH-3T3 | >25 (20%)b |

MIC = the lowest drug concentration completely to arrest germination and growth after 48 h at 37 °C. Fungal strains were grown in RPMI-MOPS (moulds) or in YPD (yeast), mammalian cell lines were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and bacteria were grown in LB broth.

MIC (cell culture) = % growth inhibition at 25 μM bromoquinol, as measured by the XTT assay.

Antifungal activity spectrum of the quinoline bromoquinol

We tested bromoquinol activity on a wide range of pathogenic fungal strains, mammalian cell lines and bacteria in culture (Table 2). Bromoquinol was effective against A. fumigatus spp. (0.06 < MIC < 1 μM) and Candida spp. (1 < MIC < 4 μM). Zygomycetes (Rhizopus species) were less susceptible with MICs of 16–32 μM or higher after 48 h. Bromoquinol only weakly inhibited NIH-3T3 (by 20%) and A549 cell (by 10%) proliferation at 25 μM, measured with the XTT cell viability assay. These data show that bromoquinol was much more potent at inhibiting fungal growth as compared with mammalian cell lines. The bacterial strains were weakly susceptible to bromoquinol, with MIC values of 12.5 or 25 μM, indicating that it was not entirely fungus specific. We tested the fungicidal activity of bromoquinol against A. fumigatus Af293 and Candida albicans CBS562. Bromoquinol achieved 95% killing at 8 μM in A. fumigatus (minimal fungicidal concentration 32 μM) and in C. albicans 99% killing at 1 μM (minimal fungicidal concentration 1 μM). Bromoquinol did not cause haemolysis of sheep red blood cells after 24 h at a concentration of 25 μM, indicating that it does not act as a non-specific membrane-disrupting agent (data not shown).

Bromoquinol activity is abolished by addition of Fe3+, Cu2+ or Zn

We tested the effect of increasing iron concentrations on growth inhibition (MIC) of A. fumigatus (Af293), A. nidulans (R153) and C. albicans (CBS562) by bromoquinol (Table 3). Addition of iron to MM lacking iron at concentrations between 2 and 32 μM gradually abolished growth inhibition by bromoquinol. In all three fungi, this effect was already evident at 2–8 μM of iron indicating that bromoquinol acts in a similar manner. Further analysis in A. fumigatus (Af293) demonstrated that increased levels of the metals zinc and copper at similar concentrations also abolished inhibition by bromoquinol (Tables S3 and S4). Addition of a strong chelator of Cu2+ (bathocuprine disulfonic acid) or Fe3+ (triacetyl fusarinine) restored bromoquinol inhibition in the presence of excess copper or iron addition, demonstrating that Fe3+/Cu2+ inactivation of bromoquinol is reversible (Tables S5 and S6).

Effect of different Fe3+ concentrations on MICs of bromoquinol for A. fumigatus, A. nidulans and C. albicans

| Fe3+ concentration (μM) . | MIC (μM) for A. fumigatus (Af293) . | MIC (μM) for A. nidulans (R153) . | MIC (μM) for C. albicans (ATCC 2901) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| 8 | 8 | 32 | 4 |

| 16 | 16 | 32 | 16 |

| 32 | 32 | >32 | 32 |

| 64 | 32 | >32 | >32 |

| 128 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| Fe3+ concentration (μM) . | MIC (μM) for A. fumigatus (Af293) . | MIC (μM) for A. nidulans (R153) . | MIC (μM) for C. albicans (ATCC 2901) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| 8 | 8 | 32 | 4 |

| 16 | 16 | 32 | 16 |

| 32 | 32 | >32 | 32 |

| 64 | 32 | >32 | >32 |

| 128 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

Effect of different Fe3+ concentrations on MICs of bromoquinol for A. fumigatus, A. nidulans and C. albicans

| Fe3+ concentration (μM) . | MIC (μM) for A. fumigatus (Af293) . | MIC (μM) for A. nidulans (R153) . | MIC (μM) for C. albicans (ATCC 2901) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| 8 | 8 | 32 | 4 |

| 16 | 16 | 32 | 16 |

| 32 | 32 | >32 | 32 |

| 64 | 32 | >32 | >32 |

| 128 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| Fe3+ concentration (μM) . | MIC (μM) for A. fumigatus (Af293) . | MIC (μM) for A. nidulans (R153) . | MIC (μM) for C. albicans (ATCC 2901) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| 8 | 8 | 32 | 4 |

| 16 | 16 | 32 | 16 |

| 32 | 32 | >32 | 32 |

| 64 | 32 | >32 | >32 |

| 128 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

Structure–activity relationships of related quinolines

We carried out a structure–activity relationship analysis of three commercially available quinolines in comparison with bromoquinol. MICs were determined for A. fumigatus Af293 grown for 48 h on RPMI-MOPS (Table 4). Replacement of the Br residues at positions 5 and 6 in bromoquinol with Cl (in dichloro 8-hydroxyquinoline) or I and Cl (in 5-chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline/clioquinol) did not improve antifungal activity (MIC 1 μM for all three compounds). Removal of the halogenated residues at these positions (in 8-hydroxyquinoline) strongly reduced activity (MIC 32 μM). Addition of iron or zinc strongly reduced the antifungal activity of all of the quinolines tested. Interestingly, whereas addition of copper strongly reduced the antifungal activity of the halogenated quinolines, it strongly increased the activity of 8-hydroxyquinoline (MIC − Cu2+ = 32 μM, MIC + Cu2+ = 2 μM).

| Compound name . | Structure . | MIC (−iron) . | MIC (+irona) . | MIC (+zincb) . | MIC (+copperc) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromoquinol |  | 1 | >32 | 32 | 32 |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline |  | 32 | >32 | >32 | 2 |

| 5-Chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline (clioquinol) |  | 1 | >32 | 8 | 16 |

| 5,7-Dichloro-8-hydroxyquinoline |  | 1 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Compound name . | Structure . | MIC (−iron) . | MIC (+irona) . | MIC (+zincb) . | MIC (+copperc) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromoquinol |  | 1 | >32 | 32 | 32 |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline |  | 32 | >32 | >32 | 2 |

| 5-Chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline (clioquinol) |  | 1 | >32 | 8 | 16 |

| 5,7-Dichloro-8-hydroxyquinoline |  | 1 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

Iron (FeCl2) = 64 μM.

Zinc (ZnSO4) = 64 μM.

Copper (CuSO4) = 3 μM.

| Compound name . | Structure . | MIC (−iron) . | MIC (+irona) . | MIC (+zincb) . | MIC (+copperc) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromoquinol |  | 1 | >32 | 32 | 32 |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline |  | 32 | >32 | >32 | 2 |

| 5-Chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline (clioquinol) |  | 1 | >32 | 8 | 16 |

| 5,7-Dichloro-8-hydroxyquinoline |  | 1 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Compound name . | Structure . | MIC (−iron) . | MIC (+irona) . | MIC (+zincb) . | MIC (+copperc) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromoquinol |  | 1 | >32 | 32 | 32 |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline |  | 32 | >32 | >32 | 2 |

| 5-Chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline (clioquinol) |  | 1 | >32 | 8 | 16 |

| 5,7-Dichloro-8-hydroxyquinoline |  | 1 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

Iron (FeCl2) = 64 μM.

Zinc (ZnSO4) = 64 μM.

Copper (CuSO4) = 3 μM.

Screening an A. nidulans overexpression genomic library for resistance-conferring plasmids

To identify the molecular target of bromoquinol, we screened a multicopy non-integrating genomic library of A. nidulans based on the high copy vector pRG3-AMA1.19 Conidia (5 × 104/mL) of the library were plated under bromoquinol (8–10 μM) selection in MM without iron. After 6 days at 37°C, five resistant colonies were identified and the multicopy library vector from all transformants was isolated. These plasmids were transformed once more into A. nidulans via transformation by protoplasting21 and one of them conferred resistance to bromoquinol and two other halogenated quinolines, but not to 8-hydroxyquinoline or the antifungals caspofungin, voriconazole or amphotericin B (Table 5). Sequencing of the plasmid revealed that it contained three genes, dbaA (AN7896), dbaB (AN7897) and dbaD (AN7898), composing part of a secondary metabolite cluster. To identify which of these genes conferred bromoquinol resistance, we used transposon mutagenesis mapping. We searched for single insertions that caused the A. nidulans resistant strain to lose resistance to bromoquinol upon transformation, as this is expected to occur in the rescuing gene. Sequencing of the area bordering the single transposon insertion revealed that resistance-inactivating insertions occurred separately in two of the three genes: dbaA and dbaD. These genes are both members of the dba secondary metabolite gene cluster. The putative cluster spans 12 genes in total. Of the 12 genes, dbaA encodes a Zn(II)2Cys6 transcription factor with a role in activating the cluster and dbaD encodes a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter with a possible role in secreting the secondary metabolite made by the cluster.22 We propose that overexpression of the DbaD transporter may confer resistance to the halogenated quinolines by specifically increasing their efflux (see the Discussion section).

MICs of quinolines and antifungals for resistant A. nidulans An-AMA pdbaA/B/D and control An-AMA strains

| . | Bromoquinol (μM) . | 5-Chloro-7-iodo- 8-quinolinol (μM) . | 5,7-Dichloro- 8-hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | 8-Hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | Voriconazole (mg/L) . | Caspofungin (mg/L) . | Amphotericin B (mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An-AMAa | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

| An-AMA pdbaA/B/D | 2 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

| . | Bromoquinol (μM) . | 5-Chloro-7-iodo- 8-quinolinol (μM) . | 5,7-Dichloro- 8-hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | 8-Hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | Voriconazole (mg/L) . | Caspofungin (mg/L) . | Amphotericin B (mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An-AMAa | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

| An-AMA pdbaA/B/D | 2 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

Control A. nidulans strain containing the empty AMA cloning vector.

MEC values.

MICs of quinolines and antifungals for resistant A. nidulans An-AMA pdbaA/B/D and control An-AMA strains

| . | Bromoquinol (μM) . | 5-Chloro-7-iodo- 8-quinolinol (μM) . | 5,7-Dichloro- 8-hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | 8-Hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | Voriconazole (mg/L) . | Caspofungin (mg/L) . | Amphotericin B (mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An-AMAa | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

| An-AMA pdbaA/B/D | 2 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

| . | Bromoquinol (μM) . | 5-Chloro-7-iodo- 8-quinolinol (μM) . | 5,7-Dichloro- 8-hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | 8-Hydroxyquinoline (μM) . | Voriconazole (mg/L) . | Caspofungin (mg/L) . | Amphotericin B (mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An-AMAa | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

| An-AMA pdbaA/B/D | 2 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 0.125 | 0.125b | 1 |

Control A. nidulans strain containing the empty AMA cloning vector.

MEC values.

Bromoquinol activates genes involved in oxidation–reduction, efflux and secondary metabolite clusters

To gain further insight into the mode of action of bromoquinol, we performed RNAseq analysis of A. fumigatus cells exposed to the compound (see Supplementary data for experimental details). A. fumigatus (Af293) conidia were germinated in MM without iron for 16 h at 37°C and treated with 2 μM bromoquinol for 1 h. The mycelium was harvested, total RNA prepared and used to generate cDNA libraries that were sequenced with the Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument. Differential expression analysis revealed 8800 expressed genes (87% of the genes in the A. fumigatus genome). Bromoquinol treatment increased the expression of 1025 genes by >2-fold. Of these, 906 annotated genes were evaluated by GO/gene ontology term enrichment analysis. Significantly enriched up-regulated gene categories included secondary metabolite clusters (P = 7.8 × 10−20), transporters (P = 4.9 × 10−13) and genes involved in oxidation–reduction (P = 3.7 × 10−19) (Table 6 and Table S7). Up-regulated transporters included 51 MFS and 11 ABC transporters and among them two homologues of the dbaD transporter (Afu3g03320, Afu1g05170) identified above in A. nidulans as conferring bromoquinol resistance. However, this transcriptional activation does not lead to resistance, as this requires expression from multiple copies of the gene as seen in A. nidulans. Interestingly genes from 14 of the 31 secondary metabolite clusters found in A. fumigatus were up-regulated by bromoquinol, including the gliotoxin, NRPS1, fumigaclavine C and trypacidin clusters. Up-regulated genes involved in oxidation–reduction included 20 glutathione S-transferase genes that encode proteins that can detoxify H2O2, 20 cytochrome P450 oxidoreductases and 16 FAD-dependent oxidoreductases, suggesting that the fungus is experiencing oxidative stress. Notably two putative pro-apoptotic genes (Afu3g01290, Afu2g00230) with homology to yeast apoptosis inducing factor were also activated.

Selected enriched up-regulated and down-regulated genes in A. fumigatus in response to bromoquinol

| Category . | n . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | ||

| secondary metabolite clusters | 56 | 7.2E−20 |

| transporters | 74 | 4.9E−13 |

| oxidation–reduction | 121 | 3.7E−19 |

| Down-regulated genes | ||

| ribosome biogenesis | 120 | 1.1E−81 |

| nitrogen compound metabolism | 168 | 2.4E−26 |

| primary metabolic process | 367 | 1.1E−16 |

| Category . | n . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | ||

| secondary metabolite clusters | 56 | 7.2E−20 |

| transporters | 74 | 4.9E−13 |

| oxidation–reduction | 121 | 3.7E−19 |

| Down-regulated genes | ||

| ribosome biogenesis | 120 | 1.1E−81 |

| nitrogen compound metabolism | 168 | 2.4E−26 |

| primary metabolic process | 367 | 1.1E−16 |

Selected enriched up-regulated and down-regulated genes in A. fumigatus in response to bromoquinol

| Category . | n . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | ||

| secondary metabolite clusters | 56 | 7.2E−20 |

| transporters | 74 | 4.9E−13 |

| oxidation–reduction | 121 | 3.7E−19 |

| Down-regulated genes | ||

| ribosome biogenesis | 120 | 1.1E−81 |

| nitrogen compound metabolism | 168 | 2.4E−26 |

| primary metabolic process | 367 | 1.1E−16 |

| Category . | n . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | ||

| secondary metabolite clusters | 56 | 7.2E−20 |

| transporters | 74 | 4.9E−13 |

| oxidation–reduction | 121 | 3.7E−19 |

| Down-regulated genes | ||

| ribosome biogenesis | 120 | 1.1E−81 |

| nitrogen compound metabolism | 168 | 2.4E−26 |

| primary metabolic process | 367 | 1.1E−16 |

Significantly enriched down-regulated gene categories most notably included genes involved in ribosome biogenesis (P = 1.1 × 10−81) and among them many genes encoding translation initiation factors, ribosomal proteins and ribosomal RNA processing and assembly factors (Table 6 and Table S7).

We used RT-qPCR to analyse the mRNA levels of five key genes showing up-regulation after RNA sequencing, following exposure to bromoquinol compared with untreated Af293. The RT-qPCR analysis validated the results of the RNAseq, including up-regulation of the two A. fumigatus dbaD homologues Afu3g03320 and Afu1g05170 (Table 7 and Supplementary data).

| . | . | RNAseq . | RT-qPCR . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene . | Description . | fold change . | P . | fold change . | SD . |

| Afu3g03320 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 13 | 2.77E−16 | 36 | 0.7 |

| Afu1g05170 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 3.9 | 2.39E−23 | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| Afu3g01400 | ABC multidrug transporter | 19.5 | 1.71E−99 | 126 | 1.3 |

| Afu3g01290 | AMID-like mitochondrial oxidoreductase | 14.6 | 2.04E−15 | 93 | 1.3 |

| Afu4g14530 | glutathione S-transferase Ure2-like | 16 | 1.33E−19 | 70 | 0.1 |

| . | . | RNAseq . | RT-qPCR . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene . | Description . | fold change . | P . | fold change . | SD . |

| Afu3g03320 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 13 | 2.77E−16 | 36 | 0.7 |

| Afu1g05170 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 3.9 | 2.39E−23 | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| Afu3g01400 | ABC multidrug transporter | 19.5 | 1.71E−99 | 126 | 1.3 |

| Afu3g01290 | AMID-like mitochondrial oxidoreductase | 14.6 | 2.04E−15 | 93 | 1.3 |

| Afu4g14530 | glutathione S-transferase Ure2-like | 16 | 1.33E−19 | 70 | 0.1 |

| . | . | RNAseq . | RT-qPCR . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene . | Description . | fold change . | P . | fold change . | SD . |

| Afu3g03320 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 13 | 2.77E−16 | 36 | 0.7 |

| Afu1g05170 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 3.9 | 2.39E−23 | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| Afu3g01400 | ABC multidrug transporter | 19.5 | 1.71E−99 | 126 | 1.3 |

| Afu3g01290 | AMID-like mitochondrial oxidoreductase | 14.6 | 2.04E−15 | 93 | 1.3 |

| Afu4g14530 | glutathione S-transferase Ure2-like | 16 | 1.33E−19 | 70 | 0.1 |

| . | . | RNAseq . | RT-qPCR . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene . | Description . | fold change . | P . | fold change . | SD . |

| Afu3g03320 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 13 | 2.77E−16 | 36 | 0.7 |

| Afu1g05170 | MFS monocarboxylate transporter dbaD homologue | 3.9 | 2.39E−23 | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| Afu3g01400 | ABC multidrug transporter | 19.5 | 1.71E−99 | 126 | 1.3 |

| Afu3g01290 | AMID-like mitochondrial oxidoreductase | 14.6 | 2.04E−15 | 93 | 1.3 |

| Afu4g14530 | glutathione S-transferase Ure2-like | 16 | 1.33E−19 | 70 | 0.1 |

Taken together, the transcriptional profile indicated that after exposure to bromoquinol, A. fumigatus drastically reduced energy-consuming cellular activities and in particular protein synthesis. It activated a large number of genes apparently involved in drug efflux and detoxification of bromoquinol and in response to reactive radical formation.

Bromoquinol induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in A. fumigatus

Based on the RNAseq results showing significant activation of glutathione S-transferase genes and oxidoreductases after bromoquinol treatment, we directly assayed the cells for oxidative stress. We used the fluorescent dye DCFDA that measures reactive oxygen species within the cell. A. fumigatus (Af293) hyphae treated for 1 h with 10 μM bromoquinol in the presence of DCFDA fluoresced to an extent similar to that following treatment with the known reactive oxygen species stressor menadione, indicating that bromoquinol strongly induced oxidative stress (Figure 2a). Because oxidative stress is a strong activator of apoptotic cell death, we carried out two independent assays to evaluate if bromoquinol-treated A. fumigatus hyphae underwent apoptosis. Fungal apoptosis, determined by nuclear DAPI staining, revealed extensive chromatin condensation and fragmentation in A. fumigatus treated for 2 h with 10 μM bromoquinol, similar in extent to the apoptosis induced by H2O2 treatment (Figure 2b). The detection of apoptosis-induced DNA strand breaks by TUNEL showed that protoplasts treated with 10 μM bromoquinol for 2 h at 37°C exhibited nuclear fluorescence indicative of double-strand break formation similar to that shown by treatment with 0.1 mM H2O2 (Figure 2c). In summary, these results indicate that bromoquinol induces rapid oxidative stress and apoptosis in A. fumigatus.

Bromoquinol induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in A. fumigatus. A. fumigatus conidia were grown for 16 h at 37 °C. Addition of 10 μM bromoquinol-induced (a) oxidative stress as measured by DCFDA fluorescence. (b) Nuclear DNA fragmentation and (c) TUNEL DNA double-strand break formation in protoplasts, both characteristic of fungal apoptosis. BQ, bromoquinol, H2O2, a known inducer of apoptosis; MND, menadione, a known inducer of oxidative stress. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

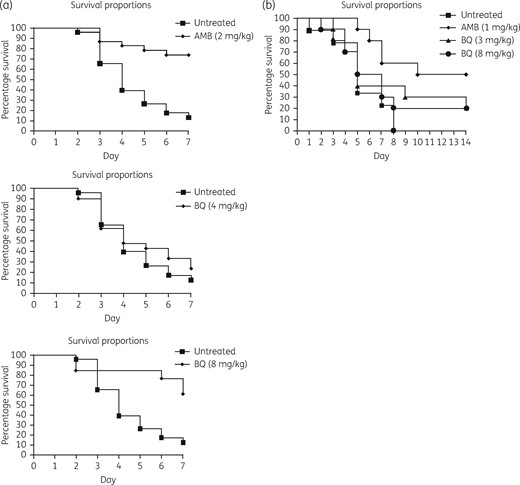

Bromoquinol reduces mortality in G. mellonella larvae infected with A. fumigatus

To evaluate the efficacy of bromoquinol in treating invasive aspergillosis, we used the G. mellonella infection model. Infected larvae were injected with bromoquinol at different concentrations (ranging from 4 to 8 mg/kg) or with 2 mg/kg amphotericin B as a positive treatment control (Figure 3a). Bromoquinol was not effective at a concentration of 4 mg/kg (P = 0.43; 4 mg/kg 20% survival after 7 days), but showed efficacy at 8 mg/kg (P = 0.0024; 60% survival after 7 days) similar to that of the proven antifungal amphotericin B (P < 0.0001; 60% survival after 7 days).

Bromoquinol reduces mortality in G. mellonella larvae infected with A. fumigatus. (a) Bromoquinol at a concentration of 8 mg/kg significantly (P = 0.0024) reduced mortality of Galleria larvae injected with 5 × 105 conidia of A. fumigatus. (b) Bromoquinol at a concentration of up to 8 mg/kg did not reduce mortality in immunosuppressed mice inoculated intranasally with 5 × 105 conidia of A. fumigatus. Antifungal amphotericin B was used as a positive treatment control. AMB, amphotericin B; BQ, bromoquinol.

Bromoquinol is ineffective in a murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

Mice were immunosuppressed with cortisone acetate and infected by intranasal inoculation with A. fumigatus conidia. Treatment was performed by intraperitoneal injection 2 h after infection and on the next two consecutive days. Survival in each group (n = 10) was monitored over 14 days. Whereas the control antifungal amphotericin B significantly reduced mortality (P = 0.004; 50% mortality after 14 days), treatment with bromoquinol at 3 mg/kg (P = 0.34) or 8 mg/kg (P = 0.43) was ineffective (Figure 3b).

Discussion

A novel antifungal screen identified compounds interfering with key virulence-associated metabolic pathways in A. fumigatus

We performed a novel screen of small molecular drug-like compounds to identify inhibitors that specifically interfere with unique fungal pathways (iron uptake, vitamin pathways, aromatic amino acid synthesis) not found in humans and essential for virulence.8–11,13 We focused on the study of bromoquinol because it was highly potent (at low micromolar concentrations) in the absence of iron, and lost all activity upon addition of iron. We found that bromoquinol is fungus-specific in vitro and active in an insect model of infection, but ineffective in a murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. The lack of bromoquinol activity in the latter model might have several explanations, such as bromoquinol binding by serum, rapid rate of clearance and limited penetration into the infected lungs. Further optimization and study of the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of bromoquinol in the murine model is needed.

Importantly, bromoquinol would have probably been discarded in a standard screen because it is a weak antifungal in most fungal media that contain iron at high micromolar levels. This is an example of drug discovery that capitalizes on the important environmental cues of in vivo growth, specifically the conditions of scarcity of essential elements such as iron.

Bromoquinol exhibits divalent metal-dependent antifungal activity in vitro and in vivo

Bromoquinol is a brominated derivative of the agricultural fungicide and antimicrobial 8-hydroxyquinoline.23 8-Hydroxyquinoline forms weak to moderate affinity complexes with divalent metal ions such as zinc, copper and iron. Therefore, it was suggested that 8-hydroxyquinoline acts in fungi by chelating metals, such as zinc, copper and iron, and inhibiting cellular metal-dependent catalysis.24 Clioquinol (5-chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline), in addition to antimicrobial activity, showed efficacy in mouse models of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease.25 The in vitro activity of bromoquinol against pathogenic yeasts was recently demonstrated, but its mode of action was not described.26

Resistance to bromoquinol in A. nidulans is conferred by overexpression of dbaD encoding a secondary metabolite cluster transporter

We performed a library screen for bromoquinol resistance genes in A. nidulans and found that overexpression of dbaA (AN7896) and dbaD (AN7898) conferred resistance to bromoquinol. The dbaA and dbaD null strains,22 however, showed WT susceptibility to bromoquinol (data not shown), suggesting that in these strains additional efflux mechanisms had been activated.

dbaA and dbaD are members of the A. nidulans dba gene cluster, containing 12 genes in total, involved in the synthesis of the secondary metabolite 2,4-dihydroxy-3-methyl-6-(2-oxopropyl)benzaldehyde, that has antibacterial activity and is an intermediate in the production of the azaphilones, antimicrobial yellow pigments.22,dbaA encodes a Zn(II)2Cys6 transcription factor that activates the dba cluster and dbaD encodes an MFS transporter that is proposed to transport the metabolites produced by the cluster, into the environment.22

We showed that the two A. fumigatus dbaD homologues Afu3g03320 and Afu1g05170 are also up-regulated in response to bromoquinol. Interestingly, based on our analysis of published transcriptome datasets, these two genes are not up-regulated in response to the conventional antifungals caspofungin, voriconazole and amphotericin B,27–29 but are strongly up-regulated under hypoxia30 and haem starvation (Hubertus Haas, personal communication). This suggests that activation of the dba cluster may be partly controlled by the transcription factor SrbA that controls the hypoxic response, which includes activation of haem biosynthesis.31 Taken together, our findings suggest that overexpression of the dbaA transcription factor and dbaD transporter could result in increased efflux of bromoquinol from the fungal cell and therefore increased resistance, although this needs to be rigorously assessed by measuring the efflux of radioactively-labelled bromoquinol. This finding is conceptually important because it suggests that secondary metabolite cluster efflux transporters, in addition to secreting secondary metabolites, can also be co-opted to rid the cell of toxic compounds found in its environment, including antifungal compounds.

Proposed mode of action of bromoquinol

Bromoquinol functions as an inducible antifungal. In the presence of iron, copper or zinc, bromoquinol is chelated and inactive. Under conditions of low concentrations of these metals, as found in the infected host, active bromoquinol monomers are released. The bromoquinol monomers inside the fungal cell bind to iron, copper or zinc coordinated into the active site of metalloenzymes, and in particular oxidoreductases.24 This interferes with their catalytic functions, disrupting the redox potential of the cell and inducing oxidative stress leading to apoptosis and cell death as shown in the Results section. An alternative model, in which bromoquinol acts by chelating intracellular metals, can be discarded for several reasons, e.g. (i) most fungi, including A. fumigatus possess endogenous metal chelators such as siderophores with much higher affinities than bromoquinol, and (ii) the RNAseq analysis provides no evidence that bromoquinol induces the expression of genes associated with metal starvation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, bromoquinol presents novel opportunities for the development of inducible antifungals. Future directions include generating bromoquinol derivatives conjugated to existing antifungals that will dissociate and act under the low iron/copper/zinc concentrations found in fungus-infected tissue.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gilgi Freidlander for performing the bioinformatics analysis of the RNAseq data, Hubertus Haas for kindly providing us with triacetyl fusarinine and for useful discussions and Amir Sharon for his help in the apoptosis analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by The Binational Science Foundation (BSF) 2011322 grant to N. O. and D. P. K.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Supplementary methods, Tables S1 to S7 and Figure S1 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online (http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/).