-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Olivier Join-Lambert, Hélène Coignard-Biehler, Jean-Philippe Jais, Maïa Delage, Hélène Guet-Revillet, Sylvain Poirée, Sabine Duchatelet, Vincent Jullien, Alain Hovnanian, Olivier Lortholary, Xavier Nassif, Aude Nassif, Efficacy of ertapenem in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a pilot study in a cohort of 30 consecutive patients, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 71, Issue 2, February 2016, Pages 513–520, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv361

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is an inflammatory skin disease typically localized in the axillae and inguinal and perineal areas. In the absence of standardized medical treatment, severe HS patients present chronic suppurative lesions with polymicrobial anaerobic abscesses. Wide surgery is the cornerstone treatment of severe HS, but surgical indications are limited by the extent of lesions. Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics may help control HS, but their efficacy is not documented. This study was designed to assess the efficacy of a 6 week course of ertapenem (1 g daily) and of antibiotic consolidation treatments for 6 months (M6) in severe HS.

Thirty consecutive patients with severe HS were retrospectively included in this study. The clinical severity of HS was assessed using the Sartorius score, which takes into account the number and severity of lesions.

The median (IQR) Sartorius score dropped from 49.5 (28–62) at baseline to 19.0 (12–28) after ertapenem (P < 10−4). Five patients were lost to follow-up thereafter. At M6 the Sartorius score further decreased for the 16 patients who received continuous consolidation treatments, since 59% of HS areas reached clinical remission at M6 (i.e. absence of any inflammatory symptoms, P < 10−4). Nine patients interrupted or received intermittent consolidation treatments due to poor observance or irregular follow-up. Their Sartorius score stopped improving or returned to baseline. No major adverse event occurred.

Ertapenem can dramatically improve severe HS. Consolidation treatments are needed to further improve HS and are mandatory to prevent relapses. Combined with surgery, optimized antibiotic treatments may be promising in severe HS.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the hair follicle characterized by recurrent or chronic inflammatory lesions of the axillae, groin, buttocks and perineal areas.1 The disease begins after puberty and 30% of patients have a familial form of the disease with an autosomal dominant transmission pattern. Loss-of-function mutations in γ-secretase genes, more frequently in the NCSTN (nicastrin) gene, have been identified in <15% of HS patients.2–4 However, the pathophysiology of the disease remains enigmatic and may involve a combination of genetic, immunological and infectious factors. In the absence of satisfactory medical treatment, the impact of HS on the quality of life is among the highest compared with other chronic dermatological diseases such as acne, psoriasis or atopic eczema.5 With a prevalence of 0.1%–1%, HS is responsible for an important morbidity and social cost.5

The most prevalent form of the disease (80% of patients) is characterized by recurrent and/or chronic deep-seated painful nodules (referred to as stage 1 lesions of Hurley's clinical severity staging). These lesions can lead to abscesses, transient incapacity to work and surgery.6 Some 10%–20% of patients develop chronic suppurative lesions with draining sinuses and perilesional inflammation referred to as ‘hypertrophic scars’ (Hurley stage 2 lesions) that can involve a whole anatomical region (Hurley stage 3 lesions). These severe forms of HS do not respond reliably to 13-cis-retinoic acid, biotherapies or a variety of usual antibiotic treatments7,8 and are responsible for prolonged incapacity or invalidity. Wide surgery is the only satisfactory treatment option for these patients,5 but considering the size and number of lesions, these patients are frequently poor surgical candidates.

We recently showed that a polymorphous anaerobic microflora including strict anaerobes, streptococci of the milleri group and anaerobic actinomycetes is associated with chronic HS lesions.9 Consistent with this is the efficacy of the combination of rifampicin and clindamycin, which can be responsible for clinical remission of mild (Hurley stage 1) HS lesions.10,11 However, severe HS patients were only temporarily improved and frequently relapsed during this treatment, suggesting emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Considering these suboptimal results, we developed an alternative treatment strategy using the rifampicin/moxifloxacin/metronidazole oral combination preceded by a 3 week course of ceftriaxone and metronidazole in patients with severe HS.12 Clinical remission (i.e. absence of any inflammatory symptoms) of Hurley stage 2 lesions was obtained in 3–6 months. Although improved by these treatments, clinical remission of Hurley stage 3 areas was rare and lesions frequently relapsed after discontinuation of metronidazole.

These data prompted us to optimize our treatment using ertapenem instead of the ceftriaxone/metronidazole induction treatment in patients with severe HS, thus extending the duration of optimal antianaerobic coverage. Indeed, ertapenem is an intravenous β-lactam antibiotic that can be used to treat complicated skin and soft tissue infections13,14 and its antimicrobial spectrum covers the complex microflora of HS lesions including anaerobes and anaerobic actinomycetes.15,16 This carbapenem does not cover Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter spp. and methicillin-resistant staphylococci, which are not associated with HS lesions at baseline.9 In this work, we assessed the efficacy and tolerance of a 6 week course of ertapenem followed by consolidation treatment based on the rifampicin/moxifloxacin/metronidazole combination.

Patients and methods

Patients

Thirty consecutive patients with severe HS who were treated in our centre between December 2009 and May 2011 using ertapenem as first-line treatment were included in this study. Patients were not surgical candidates or refused surgical intervention. Topical and systemic steroids as well as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and topical antibiotics were discontinued ≥1 month before starting ertapenem, except for one patient who was receiving corticosteroids, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil for kidney transplantation.

Microbiology

The microbiology of HS lesions was assessed by swabbing before antimicrobial treatment using the Portagerm® system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France). We previously showed that this sampling method is accurate to identify bacterial pathogens associated with suppurative HS lesions.9 Briefly, swabs were seeded onto agar plates including a Uriselect4 medium plate (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), a colistin/nalidixic acid blood agar plate (CAN; bioMérieux) and a Columbia horse blood agar plate (bioMérieux). Uriselect4 and CAN agar plates were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2. Columbia horse blood agar plates were incubated anaerobically for 2 weeks. Bacterial identification was performed by MALDI-TOF MS.17,18

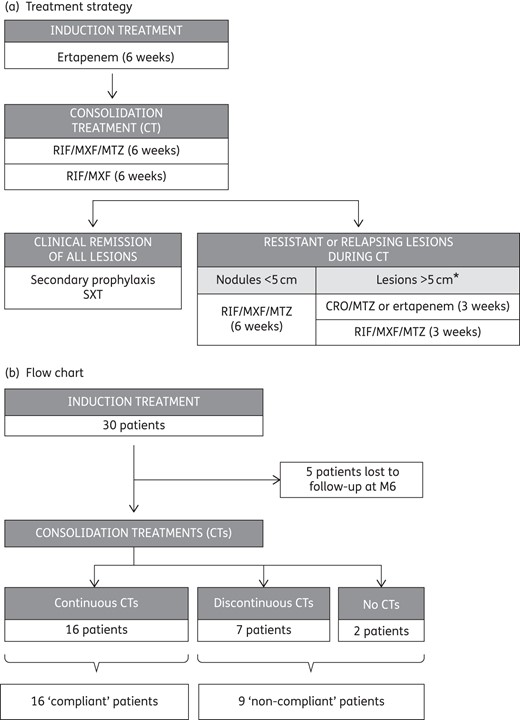

Treatment strategy

The treatment strategy consisted of a 6 week course of ertapenem (induction treatment), followed by consolidation treatments described in Figure 1(a). This treatment strategy was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes ‘Ile de France 2’ (10 July 2013, ref. 1072).

Treatment strategy and flow chart. *When the lesions were >5 cm in diameter, ceftriaxone and metronidazole, or a new course of ertapenem in patients with a high number of persisting active HS areas, were prescribed for 3 weeks, followed by a new oral consolidation treatment. Ertapenem, 1 g daily; ceftriaxone (CRO), 1 g daily; rifampicin (RIF), 10 mg/kg once daily; moxifloxacin (MXF), 400 mg once daily; metronidazole (MTZ), 500 mg three times daily; co-trimoxazole (SXT), 400 mg once daily.

Ertapenem infusions (1 g daily) were performed at home through a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in 29 cases and a peripheral catheter in 1 case. In the absence of contraindication, consolidation treatment consisted of the rifampicin/moxifloxacin/metronidazole combination for 6 weeks, followed by rifampicin and moxifloxacin alone for 6 weeks to avoid neurological side effects of metronidazole. In four cases, rifampicin (n = 3) or metronidazole (n = 1) was replaced by pristinamycin due to contraindications (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). During consolidation treatments, moxifloxacin (in five cases) or metronidazole (in one case) was switched to pristinamycin due to mild adverse events.

When clinical remission of all lesions was observed during a follow-up visit, a secondary prophylaxis was prescribed (co-trimoxazole). When a relapse occurred after discontinuation of metronidazole during consolidation treatments, the antimicrobial spectrum of the antibiotic combination was broadened to obtain a better antianaerobic coverage as summarized in Figure 1(a). When the lesions were >5 cm in diameter, ceftriaxone and metronidazole, or a new course of ertapenem in patients with a high number of persistent active HS areas, were prescribed for 3 weeks, followed by a new oral consolidation treatment.

Efficacy and tolerance of treatments

The clinical severity of HS was assessed by the same physician at baseline and at each follow-up visit every 6 weeks using the modified Sartorius score.19,20 Briefly, the Sartorius score is composed of four clinical items: (i) the number of anatomical regions with active HS; (ii) the number of nodules, fistulae, hypertrophic scars and pustules; (iii) the longest distance between two lesions (or size of lesions if single); and (iv) the presence or absence of normal skin between lesions in all areas. The global Sartorius score is calculated by adding the scores of each of these components. Clinical remission of lesions was defined by the absence of any local inflammatory sign in a given HS area. Indolent epidermal cysts, single- or multipore comedones as well as soft, non-draining, flesh-coloured skin folds were considered inactive sequelae. Subjective activity markers of HS (pain level, amount of purulent discharge and daily handicap) were assessed by patients before and after ertapenem treatment, using a visual analogical scale ranging from 0 to 10. Evolution of acute blood inflammatory markers (white blood cell count, polymorphonuclear neutrophil count and C-reactive protein) was studied when blood test results were available before and after ertapenem. Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (IQR).

Adverse events related to antibiotics or the PICC were assessed during follow-up visits.

Statistical analysis

Evolution of Sartorius scores, clinical characteristics of HS and acute inflammatory blood markers were compared using a paired Wilcoxon rank test for quantitative or ordinal values, a Mann–Whitney test for unmatched groups data and a χ2 test for trend test for comparison of categorical data. Statistical significance of factors associated with clinical remission of individual anatomical regions was tested by logistic regression, using generalized linear mixed models taking into account the dependence of observations related to the same subject (R package lme4). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Computations were performed with R 3.1 software (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Patient and lesion characteristics

The mean age of the patients was 34 years (range = 15–61 years) and the mean duration of HS was 15 years (Table 1), demonstrating the chronic nature of the disease. All patients had previously received antibiotics for HS. Seven of them had received the rifampicin/clindamycin combination and two patients were prescribed biotherapies without satisfactory results. Altogether, the 30 patients presented 133 active HS areas, including 43 Hurley stage 1, 50 Hurley stage 2 and 40 Hurley stage 3 sites.

| Patients | |

| no. of patients | 30 |

| sex ratio (male/female) | 1.1 (16/14) |

| age of patients (years), mean (SD) | 34.3 (15.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.9) |

| age at onset of HS (years), mean (SD) | 19.3 (9.6) |

| duration of HS (years), mean (SD) | 15.0 (13.1) |

| no. (%) of patients with familial HS | 15 (50) |

| Clinical severity of the disease | |

| no. of active HS anatomical regions per patient, median (range) | 4 (1–8) |

| cumulative no. of active HS anatomical areas in all patients | 133 |

| Hurley stage 1 areas | 43 |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | 50 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | 40 |

| Localization of HS areas, no. (% of HS areas) | |

| axillae | 39 (29) |

| inguinofemoral area | 47 (35) |

| buttocks | 23 (17) |

| gluteal cleft and perianal area | 16 (12) |

| breast | 8 (6) |

| Previous treatments of HS, no. of patients | |

| antimicrobial treatments | |

| prolonged antibiotic treatments | 17 |

| rifampicin/clindamycin combination | 7 |

| pristinamycin | 7 |

| tetracyclines | 7 |

| metronidazole | 3 |

| co-trimoxazole | 1 |

| ciprofloxacin | 1 |

| anti-inflammatory drugs and biologics | |

| corticosteroids (systemic/topical) | 4/1 |

| non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 14 |

| corticosteroids, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetila | 1 |

| biologics given for HS | 2 |

| wide surgery | 21 |

| Patients | |

| no. of patients | 30 |

| sex ratio (male/female) | 1.1 (16/14) |

| age of patients (years), mean (SD) | 34.3 (15.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.9) |

| age at onset of HS (years), mean (SD) | 19.3 (9.6) |

| duration of HS (years), mean (SD) | 15.0 (13.1) |

| no. (%) of patients with familial HS | 15 (50) |

| Clinical severity of the disease | |

| no. of active HS anatomical regions per patient, median (range) | 4 (1–8) |

| cumulative no. of active HS anatomical areas in all patients | 133 |

| Hurley stage 1 areas | 43 |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | 50 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | 40 |

| Localization of HS areas, no. (% of HS areas) | |

| axillae | 39 (29) |

| inguinofemoral area | 47 (35) |

| buttocks | 23 (17) |

| gluteal cleft and perianal area | 16 (12) |

| breast | 8 (6) |

| Previous treatments of HS, no. of patients | |

| antimicrobial treatments | |

| prolonged antibiotic treatments | 17 |

| rifampicin/clindamycin combination | 7 |

| pristinamycin | 7 |

| tetracyclines | 7 |

| metronidazole | 3 |

| co-trimoxazole | 1 |

| ciprofloxacin | 1 |

| anti-inflammatory drugs and biologics | |

| corticosteroids (systemic/topical) | 4/1 |

| non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 14 |

| corticosteroids, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetila | 1 |

| biologics given for HS | 2 |

| wide surgery | 21 |

aKidney transplantation.

| Patients | |

| no. of patients | 30 |

| sex ratio (male/female) | 1.1 (16/14) |

| age of patients (years), mean (SD) | 34.3 (15.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.9) |

| age at onset of HS (years), mean (SD) | 19.3 (9.6) |

| duration of HS (years), mean (SD) | 15.0 (13.1) |

| no. (%) of patients with familial HS | 15 (50) |

| Clinical severity of the disease | |

| no. of active HS anatomical regions per patient, median (range) | 4 (1–8) |

| cumulative no. of active HS anatomical areas in all patients | 133 |

| Hurley stage 1 areas | 43 |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | 50 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | 40 |

| Localization of HS areas, no. (% of HS areas) | |

| axillae | 39 (29) |

| inguinofemoral area | 47 (35) |

| buttocks | 23 (17) |

| gluteal cleft and perianal area | 16 (12) |

| breast | 8 (6) |

| Previous treatments of HS, no. of patients | |

| antimicrobial treatments | |

| prolonged antibiotic treatments | 17 |

| rifampicin/clindamycin combination | 7 |

| pristinamycin | 7 |

| tetracyclines | 7 |

| metronidazole | 3 |

| co-trimoxazole | 1 |

| ciprofloxacin | 1 |

| anti-inflammatory drugs and biologics | |

| corticosteroids (systemic/topical) | 4/1 |

| non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 14 |

| corticosteroids, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetila | 1 |

| biologics given for HS | 2 |

| wide surgery | 21 |

| Patients | |

| no. of patients | 30 |

| sex ratio (male/female) | 1.1 (16/14) |

| age of patients (years), mean (SD) | 34.3 (15.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.9) |

| age at onset of HS (years), mean (SD) | 19.3 (9.6) |

| duration of HS (years), mean (SD) | 15.0 (13.1) |

| no. (%) of patients with familial HS | 15 (50) |

| Clinical severity of the disease | |

| no. of active HS anatomical regions per patient, median (range) | 4 (1–8) |

| cumulative no. of active HS anatomical areas in all patients | 133 |

| Hurley stage 1 areas | 43 |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | 50 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | 40 |

| Localization of HS areas, no. (% of HS areas) | |

| axillae | 39 (29) |

| inguinofemoral area | 47 (35) |

| buttocks | 23 (17) |

| gluteal cleft and perianal area | 16 (12) |

| breast | 8 (6) |

| Previous treatments of HS, no. of patients | |

| antimicrobial treatments | |

| prolonged antibiotic treatments | 17 |

| rifampicin/clindamycin combination | 7 |

| pristinamycin | 7 |

| tetracyclines | 7 |

| metronidazole | 3 |

| co-trimoxazole | 1 |

| ciprofloxacin | 1 |

| anti-inflammatory drugs and biologics | |

| corticosteroids (systemic/topical) | 4/1 |

| non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 14 |

| corticosteroids, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetila | 1 |

| biologics given for HS | 2 |

| wide surgery | 21 |

aKidney transplantation.

The microbiology of 28 suppurative lesions from 21 patients was assessed before initiation of the treatment. A polymorphic anaerobic flora was identified in all cases (Supplementary Data). Actinomycetes and streptococci of the milleri group were cultured in 64% and 50% of sampled lesions, respectively, confirming our previous report.9

Efficacy of the course of ertapenem

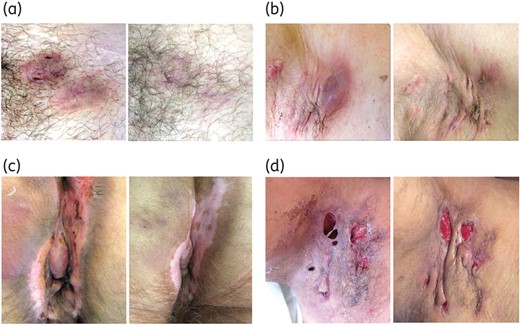

The median (IQR) Sartorius score dropped from 49.5 (28–62) to 19.0 (12–28) after the 6 week course of ertapenem (P < 10−4; Table 2), reflecting a significant decrease in the number and clinical severity of active HS areas (Table 2 and Figure 2). Consistently, patients reported an improvement of some of the activity parameters of HS with a rapid amelioration of their quality of life (Table 2). Altogether, 67% (29/43) and 26% (13/50) of Hurley stage 1 and 2 areas reached clinical remission after ertapenem, respectively.

| . | Day 0 . | Week 6 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical severity of HS | |||

| Sartorius score, median (IQR) | 49.5 (28–62) | 19.0 (12–28) | <10−4 |

| no. of active HS areas, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 3 (2–4.3) | <10−4 |

| no. of nodules, median (IQR) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–3) | 0.034 |

| no. of abscesses and fistulae, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| no. of hypertrophic scars, median (IQR) | 3.5 (2–6) | 1.5 (0–4) | <10−4 |

| no. of patients with all lesions <5 cma | 4 | 17 | |

| no. of patients with lesions 5–10 cma | 15 | 11 | 2 × 10−4 |

| no. of patients with lesions >10 cma | 11 | 1 | |

| patients without normal skin between lesions in all regions, n (%) | 13 (43) | 3 (10) | 0.004 |

| Clinical remission rates of HS areas, n/n (%)a | |||

| Hurley stage 1 areas | NA | 29/43 (67) | |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | NA | 13/50 (26) | <10−4 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | NA | 0/40 (0) | |

| Intensity of patients' self-reported HS activity parameters, median (IQR)b | |||

| daily handicap | 8 (6–9) | 3 (0–5) | <10−4 |

| suppuration | 8 (5–9) | 2 (0–3) | <10−4 |

| pain | 6 (5–8) | 0 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| Acute blood inflammatory markers, median (IQR)c | |||

| white blood cells ( × 106/mm3) | 8.9 (7.5–11.9) | 7.6 (6.9–8.5) | 0.02 |

| polymorphonuclear neutrophils (×106/mm3) | 6.0 (4.4–8.8) | 4.2 (3.6–5.0) | 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 13.8 (6.0–7.1) | 9.0 (2.0–11.5) | 0.008 |

| . | Day 0 . | Week 6 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical severity of HS | |||

| Sartorius score, median (IQR) | 49.5 (28–62) | 19.0 (12–28) | <10−4 |

| no. of active HS areas, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 3 (2–4.3) | <10−4 |

| no. of nodules, median (IQR) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–3) | 0.034 |

| no. of abscesses and fistulae, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| no. of hypertrophic scars, median (IQR) | 3.5 (2–6) | 1.5 (0–4) | <10−4 |

| no. of patients with all lesions <5 cma | 4 | 17 | |

| no. of patients with lesions 5–10 cma | 15 | 11 | 2 × 10−4 |

| no. of patients with lesions >10 cma | 11 | 1 | |

| patients without normal skin between lesions in all regions, n (%) | 13 (43) | 3 (10) | 0.004 |

| Clinical remission rates of HS areas, n/n (%)a | |||

| Hurley stage 1 areas | NA | 29/43 (67) | |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | NA | 13/50 (26) | <10−4 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | NA | 0/40 (0) | |

| Intensity of patients' self-reported HS activity parameters, median (IQR)b | |||

| daily handicap | 8 (6–9) | 3 (0–5) | <10−4 |

| suppuration | 8 (5–9) | 2 (0–3) | <10−4 |

| pain | 6 (5–8) | 0 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| Acute blood inflammatory markers, median (IQR)c | |||

| white blood cells ( × 106/mm3) | 8.9 (7.5–11.9) | 7.6 (6.9–8.5) | 0.02 |

| polymorphonuclear neutrophils (×106/mm3) | 6.0 (4.4–8.8) | 4.2 (3.6–5.0) | 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 13.8 (6.0–7.1) | 9.0 (2.0–11.5) | 0.008 |

Day 0, baseline values; week 6, values after ertapenem treatment; NA, non-attributable.

aMaximum size or distance between lesions in all anatomical regions.

bVisual analogical scale.

cBlood test results for 23 patients with available data before and after ertapenem treatment.

| . | Day 0 . | Week 6 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical severity of HS | |||

| Sartorius score, median (IQR) | 49.5 (28–62) | 19.0 (12–28) | <10−4 |

| no. of active HS areas, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 3 (2–4.3) | <10−4 |

| no. of nodules, median (IQR) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–3) | 0.034 |

| no. of abscesses and fistulae, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| no. of hypertrophic scars, median (IQR) | 3.5 (2–6) | 1.5 (0–4) | <10−4 |

| no. of patients with all lesions <5 cma | 4 | 17 | |

| no. of patients with lesions 5–10 cma | 15 | 11 | 2 × 10−4 |

| no. of patients with lesions >10 cma | 11 | 1 | |

| patients without normal skin between lesions in all regions, n (%) | 13 (43) | 3 (10) | 0.004 |

| Clinical remission rates of HS areas, n/n (%)a | |||

| Hurley stage 1 areas | NA | 29/43 (67) | |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | NA | 13/50 (26) | <10−4 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | NA | 0/40 (0) | |

| Intensity of patients' self-reported HS activity parameters, median (IQR)b | |||

| daily handicap | 8 (6–9) | 3 (0–5) | <10−4 |

| suppuration | 8 (5–9) | 2 (0–3) | <10−4 |

| pain | 6 (5–8) | 0 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| Acute blood inflammatory markers, median (IQR)c | |||

| white blood cells ( × 106/mm3) | 8.9 (7.5–11.9) | 7.6 (6.9–8.5) | 0.02 |

| polymorphonuclear neutrophils (×106/mm3) | 6.0 (4.4–8.8) | 4.2 (3.6–5.0) | 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 13.8 (6.0–7.1) | 9.0 (2.0–11.5) | 0.008 |

| . | Day 0 . | Week 6 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical severity of HS | |||

| Sartorius score, median (IQR) | 49.5 (28–62) | 19.0 (12–28) | <10−4 |

| no. of active HS areas, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 3 (2–4.3) | <10−4 |

| no. of nodules, median (IQR) | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–3) | 0.034 |

| no. of abscesses and fistulae, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| no. of hypertrophic scars, median (IQR) | 3.5 (2–6) | 1.5 (0–4) | <10−4 |

| no. of patients with all lesions <5 cma | 4 | 17 | |

| no. of patients with lesions 5–10 cma | 15 | 11 | 2 × 10−4 |

| no. of patients with lesions >10 cma | 11 | 1 | |

| patients without normal skin between lesions in all regions, n (%) | 13 (43) | 3 (10) | 0.004 |

| Clinical remission rates of HS areas, n/n (%)a | |||

| Hurley stage 1 areas | NA | 29/43 (67) | |

| Hurley stage 2 areas | NA | 13/50 (26) | <10−4 |

| Hurley stage 3 areas | NA | 0/40 (0) | |

| Intensity of patients' self-reported HS activity parameters, median (IQR)b | |||

| daily handicap | 8 (6–9) | 3 (0–5) | <10−4 |

| suppuration | 8 (5–9) | 2 (0–3) | <10−4 |

| pain | 6 (5–8) | 0 (0–2) | <10−4 |

| Acute blood inflammatory markers, median (IQR)c | |||

| white blood cells ( × 106/mm3) | 8.9 (7.5–11.9) | 7.6 (6.9–8.5) | 0.02 |

| polymorphonuclear neutrophils (×106/mm3) | 6.0 (4.4–8.8) | 4.2 (3.6–5.0) | 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 13.8 (6.0–7.1) | 9.0 (2.0–11.5) | 0.008 |

Day 0, baseline values; week 6, values after ertapenem treatment; NA, non-attributable.

aMaximum size or distance between lesions in all anatomical regions.

bVisual analogical scale.

cBlood test results for 23 patients with available data before and after ertapenem treatment.

Clinical efficacy of ertapenem in patients with severe HS. Left and right panels show HS areas before and after a 6 week course of ertapenem. (a) Clinical remission of two Hurley stage 1 lesions of the pubis. (b) Axillary Hurley stage 2 area. After ertapenem, hypertrophic scars became soft and painless with progressive disappearance of erythema and purulent discharge. (c) Anal cleft (Hurley stage 3 area). At week 6, lesions were soft, pale and stopped suppurating. (d) This patient had a Hurley stage 3 lesion of the right axilla with dermal necrosis. After ertapenem, there was no suppuration and granulation tissue formation was visible. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

White blood cells, polymorphonuclear neutrophils and C-reactive protein values were moderately elevated or in the normal range in most patients at baseline. They tended to return to normal values after ertapenem (Table 2).

Efficacy of the consolidation treatment

Twenty-five patients were evaluable at 6 months of follow-up (M6) (Figure 1b). Sixteen patients, referred to as ‘compliant patients’, received continuous consolidation treatments after ertapenem. Nine patients, referred to as ‘non-compliant patients’, received discontinuous or stopped consolidation treatments due to poor observance or irregular follow-up in seven cases and gastrointestinal intolerance in two cases (Supplementary Data).

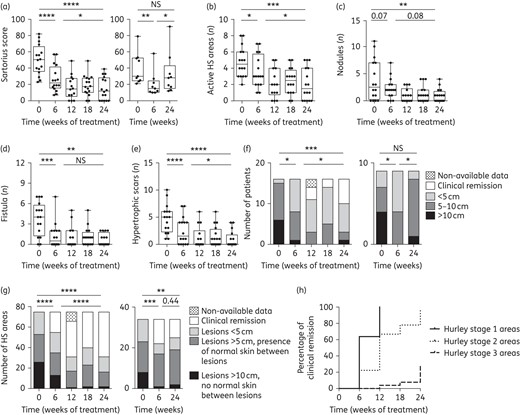

In compliant patients, the median Sartorius score significantly decreased from 50.5 (36–67) to 22.0 (16–42) after ertapenem (P < 10−4) and continued to improve during the consolidation treatment to reach a score of 12.0 (0–28) at M6 (P = 0.034 versus week 6; Figure 3a–f and Supplementary Data). Accordingly, the number of active HS areas per patient significantly decreased from 4.5 (3–6) to 3 (2–5.8) (P = 0.004) after ertapenem and further decreased to 1.5 (0–4) (P = 0.03 versus week 6) at the 6 month follow-up visit. Altogether, these 16 patients presented a cumulative number of 75 active HS areas at baseline. In these patients, the clinical remission rate of HS lesions reached 23% after ertapenem and 59% after consolidation treatments at M6 (Figure 3g).

Efficacy of antibiotic consolidation treatments. (a) Sartorius scores at baseline (day 0), after ertapenem (week 6) and during follow-up until 24 weeks (6 months). Left and right panels: compliant and non-compliant patients, respectively. The Sartorius score of compliant patients continued to improve between weeks 6 and 24. Non-compliant patients stopped improving or relapsed during consolidation treatments. Number of active HS areas (b), number of nodules (c), number of fistulae (d) and number of hypertrophic scars (e) in compliant patients. (f) Maximum lesion size in compliant and non-compliant patients (left and right panels, respectively). (g) Clinical evolution of lesions (cumulative data) in compliant and non-compliant patients (left and right panels, respectively). (h) Prognosis of clinical remission of lesions (cumulative numbers) in compliant patients according to initial clinical severity (Hurley stage) (P < 10−4). Boxes = IQR and whiskers = minimum and maximum. Median values are shown. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 10−3 and ****P ≤ 10−4. NS, not statistically significant.

During follow-up, 14 of the 16 compliant patients received reinforced treatment due to mild worsening after the discontinuation of metronidazole. Adapted to the extent of lesions (see the Patients and methods section), reinforcement of consolidation treatments controlled these relapses (reintroduction of metronidazole, ceftriaxone and metronidazole or ertapenem in four, three and seven cases, respectively; Figure 3).

We previously reported that Hurley's staging is a prognostic factor for clinical remission of lesions using antibiotics.12 Consistently, clinical remissions were obtained for 100% of Hurley stage 1 lesions, 96% of Hurley stage 2 lesions and 27% of Hurley stage 3 lesions during follow-up (P < 10−4) (Figure 3h). Most persistent active lesions at M6 were therefore Hurley stage 3 lesions, which were nevertheless significantly improved compared with the beginning of the treatment (Figure 3h and Supplementary Data).

In non-compliant patients, the median Sartorius score significantly decreased from 30.0 (25–53) to 15.0 (11–25) after ertapenem (P = 0.04), but these patients stopped improving or relapsed thereafter [median Sartorius score at M6: 28 (15–43), P = 0.02 versus week 6; Figure 3 and Supplementary Data]. The median Sartorius score for compliant and non-compliant patients was not statistically different at baseline (P = 0.17) and after the 6 week course of ertapenem (P = 0.25). Demonstrating the benefit of consolidation treatments, the Sartorius score of compliant patients was significantly lower than that of compliant patients at M6 (P = 0.05).

Altogether, these data demonstrate that a 6 week course of ertapenem can significantly improve severe HS. Consolidation treatments are essential for further improvement of lesions and are required to prevent relapses.

Adverse events

Oral and vaginal candidiasis were the most frequent side effects of the 6 week course of ertapenem treatment (8/30 patients, 27%), followed by mild gastrointestinal symptoms such as transient abdominal pain or diarrhoea (6/30 patients, 20%). Other side effects of ertapenem administration were minor headaches occurring during the infusions and asthenia (13% and 17% of patients, respectively). In one case, the PICC was removed for lymphangitis and the treatment was continued using a peripheral vein.

During consolidation treatments, gastrointestinal symptoms were the most frequent side effects (60%) followed by oral/vaginal candidiasis (50%). Two patients stopped their treatment for gastrointestinal intolerance (gastrointestinal reflux). Moxifloxacin was switched to pristinamycin in six cases for suspected tendinitis (four cases), joint pain (one case) and heart palpitations (one case). Metronidazole was stopped for dizziness in one case.

Discussion

In the absence of satisfactory medical treatment, HS remains a chronic debilitating disease.1 Although wide surgery remains the cornerstone treatment of severe HS,5 these patients are frequently not candidates for surgery due to the extent of HS areas, as illustrated by this study. Very recently, adalimumab, an anti-TNF-α antibody, was given orphan drug status for the treatment of HS by the FDA. However, response rates to adalimumab and other biologics vary among patients and these treatments are only suspensive.5 In the 1980s, some authors suggested that broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics may be useful to control HS,21,22 but to our knowledge their efficacy has not been established yet. Data presented here demonstrate that, followed by consolidation treatments, a 6 week course of ertapenem is an interesting medical option to decrease the clinical severity and number of active HS areas.

In vitro, ertapenem exerts a potent bactericidal activity against mixed cultures including anaerobes compared with other β-lactam antibiotics such as piperacillin/tazobactam or ceftriaxone.23 In addition, carbapenem resistance in anaerobes is low in the community (<1%) and has only been reported in nosocomial infections.24 Hence, it can be used as empirical treatment for polymicrobial infections. In comparison, other antibiotics previously used in HS such as clindamycin may display a limited activity due to pre-existing antimicrobial resistance.25,26 The pharmacokinetics of ertapenem allows injection once daily and it can be administered at home, therefore limiting the cost of hospitalization. Finally, ertapenem is a well-tolerated intravenous drug, limiting the risk of interrupted treatments due to non-observance or intolerance.

In this work, ertapenem induced a 50% reduction of the Sartorius score and a rapid improvement of the quality of life, demonstrating the interest of this antibiotic in the medical management of severe HS. In ‘compliant patients’, the clinical severity continued to decrease during consolidation treatments and a majority of lesions reached clinical remission, depending on their Hurley stage. Patients who interrupted their treatment stopped improving or relapsed, demonstrating the importance of antibiotic consolidation treatments. As stated above, our major aim was to decrease the number of suppurating HS lesions to facilitate surgery. In addition, a recent study suggested that optimized antibiotic treatments can reduce post-operative wound infections due to non-optimal resections and late relapses.27 With a ≥90% clinical remission rate of Hurley stage 1 and 2 lesions and a significant improvement of persistent active HS lesions, this goal was reached in 6 months in compliant patients.

Notably, ertapenem alone induced the clinical remission of 67% of Hurley stage 1 (nodules) and of 26% of Hurley stage 2 lesions. As the disease is considered predominantly inflammatory, authors who reported clinical remission of HS lesions using the clindamycin/rifampicin combination postulated that the activity of these antibiotics in HS may be due to immunomodulating properties.10,11,28 Conversely, β-lactam antibiotics interact with bacterial peptidoglycan and induce bacterial lysis, thus promoting inflammation. In addition, imipenem, the first marketed carbapenem, is considered an immunoenhancing antibiotic that increases leucocyte chemotaxis and has no demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity.28 Considering that bacterial killing is the only mode of action of ertapenem, these findings support our hypothesis that bacterial factors may play an early and central role in the pathophysiology of HS.9,12 Accordingly, recent data suggest that an altered cutaneous innate immunity may account for inflammation in HS. For example, a significantly decreased expression of toll-like receptors 2, 3, 4, 7 and 9 and ribonuclease 7, a potent antimicrobial peptide, has been observed in skin biopsies of patients with HS.29,30 Altogether, these data suggest that inflammation in HS may be due to dysregulated immunity, partly driven by infectious factors.

The low clinical remission rate of Hurley stage 3 lesions is a challenging issue. These lesions are chronic deep abscesses drained by one or multiple, often interconnected, sinus tracts. The lower efficacy of antibiotics may result from impaired diffusion, pharmacokinetic issues, bacterial persisters that are tolerant to antibiotics31 or external reinfections with resistant bacteria during treatments. Alternatively, it may reflect a more important immune dysregulation.30

The main limitations of this pilot study are its retrospective and monocentric design and the absence of a control group. Even though patients were included consecutively, we cannot exclude selection bias. However, considering that all patients suffered from long-lasting HS, the favourable evolution of the disease under ertapenem treatment is unlikely to be fortuitous.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that optimized antibiotic treatments can significantly improve the clinical severity of severe HS. To take into account the risks of prolonged antimicrobial therapy and to maintain the benefit of these treatments, this medical option should be restricted to patients who are aware of the duration of the treatment and of potential side effects and who are not surgical candidates or refuse immediate surgery, but accept surgery after improvement of lesions. These results should prompt randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy of this treatment strategy in association with surgery and biotherapies.

Funding

This study was carried out as part of our routine work and was supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Roxanne Project: Pathophysiology and Treatment of Hidradenitis Suppurativa, grant number: LMV20100519581).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

References