-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Carlo Pietrobelli, Beatriz Calzada Olvera, Michiko Iizuka, Caio Torres Mazzi, Suppliers’ entry, upgrading, and innovation in mining GVCs: lessons from Argentina, Brazil, and Peru, Industrial and Corporate Change, Volume 33, Issue 4, August 2024, Pages 922–939, https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtad079

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This paper studies whether the mining sector can represent a true engine of growth for selected Latin American countries through the suppliers’ entry and upgrading within mining value chains. We start by using international trade data to study where mining value is added and how rents are distributed across countries. Despite their importance in the production and exports of copper ores and concentrate, the participation of the selected Latin American countries in copper value chains is still confined to the upstream segment. Moreover, their share of innovation relevant for the sector remains very limited, although new data on patenting and publications show that the sector is becoming increasingly innovative worldwide. Then, we use new microeconomic evidence from case-studies in Latin America to explore the specific opportunities and obstacles faced by mining suppliers in entering the value chain and upgrading within it, and how the regulatory and innovation systems have influenced this process. We show that barriers related to the contractual practices, lead firms’ attitudes, and the hierarchical industrial organization of the sector, coupled with the countries’ weaknesses in local innovation and regulatory systems, have been contributing to hamper suppliers’ entry into mining value chains and upgrading.

A big question continues to loom in academic and policy debates: can the mining sector represent a true engine of growth for developing countries? How is Latin America placed in this regard? In addition to the traditional arguments in the literature (Venables, 2016), the answer has come to depend on a number of recent developments. First of all, the quest for social and environmental sustainability in extractive industries continues and these demands will shape the future of the industry worldwide (IEA International Energy Agency, 2021). Second, extractive industries have been mainly characterized by the dominating presence of very large multinational corporations (MNC). Recently, the process of outsourcing some layers of the value chains has spread also to this sector (Pietrobelli et al., 2018), potentially opening opportunities for local suppliers that did not exist before. Third, the production process is changing, with growing demands of innovative technologies and organization, a rise in patenting, and the ensuing changing demands on suppliers in the industry.

In this paper, we start answering this question by exploring various sources of evidence, some of which are part of a long research project that involved trade and macro as well as micro case studies in three Latin American countries—Argentina, Brazil, and Peru—in which the authors have participated. We first present the organization of the industry and the typical structure of mining global value chains (GVCs) to understand the process of value creation. Thereafter, using international trade data, we present where value is actually added and how rents are distributed across countries. Then, with new data on patenting and publications relevant to the industry, we argue that the sector is becoming increasingly innovative and discuss the current role of the three countries in this process. Finally, we use microeconomic evidence from case-studies in Latin America to explore the specific opportunities and obstacles faced by mining suppliers in entering the value chain and upgrading within it, and how the regulatory context has influenced this process. The paper concludes with a summary and some thoughts on the likely future of the industry and the scope for developing countries’ producers.

We show that, despite the importance of these countries in the production and export of copper ores and concentrate, their participation in copper GVCs is still limited in several dimensions. While the sector’s take off still faces many hurdles in Argentina, Peru, and Brazil, it is largely specialized in the upstream segment, maintaining a limited participation in downstream production and, importantly, in the provision of key specialized machinery and services for mining activities. Not surprisingly, these countries have largely been spectators to the growing role of innovation in the sector, as demonstrated by the rise in patenting and publications worldwide. Against this backdrop, we show that barriers related to the practices and the internal industrial organization of the sector, coupled with these countries’ weaknesses in local innovation and regulatory systems, have been contributing to hamper innovation and upgrading by local firms.

1. The organization of copper production and the rise of GVCs

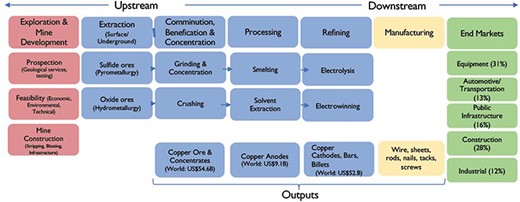

The copper mining value chain is characterized by a relatively low number of stages, low levels of geographic fragmentation, and high levels of capital intensity.1 However, the industry organization of the value chain is not necessarily simple because of several typical characteristics of the sector, including the long life-cycles of mines, the high-risk nature of exploration activities, and their geographically bounded nature. Figure 1 depicts the different upstream and downstream stages of global copper value chains. The main five upstream and midstream stages are: (i) exploration and mine development; (ii) extraction; (iii) comminution, beneficiation, and concentration; (iv) processing; and (v) refining. While there is a remarkable competition in downstream industries with a myriad of sectors fed by copper inputs, upstream activities are relatively concentrated.

The relatively low number of actors—typically large MNCs—that carry out most of the activities following different business models can be broadly categorized as follows: (i) Exploration only—juniors, i.e., firms specialized in the earlier stages of exploration; (ii) Exploration and Extraction: mining firms; (iii) Vertically integrated: mining firms and processors; (iv) Processing and Refining: processors only. Additionally, specialized engineering firms, i.e., Engineering, Procurement, Construction (EPC) and Engineering, Procurement and Construction Management (EPCM), focus on the mine construction and development stages.

The focus of this study is on the first- and second-tier suppliers of services and manufactures across the upstream segments,2 as this is the segment in which the three countries concentrate their mining activity—much like the rest of Latin America (Blyde, 2014; Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021). Peru constitutes a major global actor in copper value chains. However, its operations are almost exclusively specialized in the exploration and extraction stages, as a “miners only” model. Almost all of Peru’s ore and concentrate production is exported, with only a small share destined to the country’s one operating smelter-refinery in Ilo (Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021). The participation of Brazil and Argentina in the processing of copper is substantially less important than Peru’s.3 Given this very strong focus on upstream activities, the lion’s share of specialized suppliers in Peru, Argentina, and Brazil provide inputs and services either as juniors, to other juniors, or to miners located either in the country or in neighboring countries, such as Chile, in the exploration and extraction phases.

Moreover, there are some important differences in terms of the mining activity ownership among the three countries that need to be highlighted. In Argentina, all five mining projects are dominated by large foreign firms—this includes extraction operations, e.g., Veladero and San Jose, and exploration projects, e.g., Altar (Marin et al., 2021). In Peru, where some smaller producers also operate, the top 10 mining firms account for the bulk of copper production (96%) and only one of these firms has national ownership (Buenaventura) (Bamber et al., 2022). In Brazil, however, the situation is different, where Vale, the largest mining firm in the country and a global top-tier firm, owns the largest copper mine in Brazil, Salobo Metais (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021).

With respect to value addition in the mining industry, the corporate and countries’ strategies reflect the idea of “additive GVCs”, proposed by Kaplinsky and Morris (2016), where the primary input makes up large percentages of the final value and the process sequentially adds value to each stage. The main strategic objective of additive GVCs, like mining, is to “thicken” value-added through the development of production linkages.

Opportunities to follow such strategy in the mining GVCs—but also in other sectors—have emerged from the global fragmentation of production due to the pressure to reduce costs and the fall in the costs of ICT, transport, and logistics (Baldwin, 2012; Pietrobelli et al., 2018). Other specific trends in mining generated further fragmentation, such as the reliance on suppliers’ innovations (Urzúa, 2011; Calzada Olvera and Iizuka, 2022), the emergence of highly specialized machinery/equipment, technology, and service (METS) suppliers (Scott-Kemmis, 2013), and the demand on local suppliers to offer innovative local services linked to new areas of knowledge, such as geological studies, waste and byproducts management, automation, and IT technologies (Pietrobelli et al., 2018).

Kaplinsky and Morris (2016) warn however that the options for fracturing “additive GVCs”, though present and increasing, are often more limited than with “vertical GVCs”—which are typically manufacturing GVCs. In addition, we will see below how some GVC features in mining still represent major obstacles to the entry of local firms and to local procurement, such as lead firms’ risk aversion, absence of room for experimentation with new suppliers and new solutions, cumbersome procurement structures, and high reliance on reputation. Indeed, the development of production linkages has been proven elusive and very challenging in the Latin American region in the past decades (Atienza et al., 2018; Calzada Olvera, 2022).

2. International trade in the copper market

The international market for the “red metal” has grown markedly over the past 30 years with copper becoming an increasingly important input for manufacturing and construction, as shown in Figure 1. Today, it represents the third most consumed industrial metal after iron and aluminum (Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021). We start by looking at international trade figures of the three main products of the copper value chain: ores, anodes, and cathodes.4According to Comtrade data, in 2020 global copper exports stood at around U$129 billion, with ore and concentrates accounting for about 50% of the market and cathodes for roughly the other half. There are indications that major structural changes in demand will increase the use of copper to accomplish a “green transition”, due to the electrical vehicle substitution of internal combustion engines, the increased electrification and green energy, and the construction and public infrastructure expansion in response to global urbanization (IEA International Energy Agency, 2021).

The three countries analyzed are at different points in the evolution of the development of their mining sectors. In 2020, Chile and Peru, together with Indonesia, Australia, and Canada, accounted for 67% of global exports of ore and concentrates, which are exported mainly to the smelting and refining hubs in Asia, notably China, India, and Japan. Chile was the world leading exporter with US$21 billion in copper ore and concentrate exports. Brazil is heavily concentrated in iron ore and ranks 14th globally in copper. Argentina, in turn, has an underdeveloped mining sector that is not significant in international terms, but with large unexploited reserves. Mining accounts for only 0.46% of Argentina’s GDP and 3% of its exports, a fraction of the participation of mining in Peru’s exports (55%) and Brazil’s (12%) in 2017.

An aspect common to the three countries is the large unexplored potential for expanding production. In Argentina, only 35% of the areas with mining potential are being exploited, and very few of them have managed to effectively establish activities. Mining investments in the country are highly constrained by the cumbersome regulatory environment and by the many conflicts with local communities. Peru’s production and investments have been significant in recent years, but the country has also seen several projects stopped or delayed due to social conflicts and regulatory demands. Finally, Brazil, despite its already strong mining sector, has also very large areas of its territory untapped for mining potential. In addition, mining activities in the three countries have been subject to remarkable questioning recently, due to their impact on the environment and on local communities, and mining extraction has not grown. Recent large-scale disasters are affecting the expansion of the sector and are expected to continue.5

Peru and Brazil are mostly upstream producers (ore and concentrates), with significantly lower downstream exports (anodes and cathodes). World markets for refined copper are quite different from the market for ore and concentrates, and only Chile is among the five top exporters in both segments. Peru stands out for having a participation in refined copper significantly below the level of the other top copper exporters,6 indicating there could be some room for downstream expansion (Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021). Nonetheless, it is also important to note the reducing convenience of functionally upgrading from copper extraction into smelting and refining. The expansion of the international processing capacity—mostly driven by China (ICSG, 2018)—generated substantial economies of scale that allow smelters to operate at peak capacity while charging lower prices for copper concentrate. Such a strategy has significantly compressed the profit margins for refining: the cost of refining has fallen from 25% of the total price of refined copper in 2005 to only 7% in 2015 (Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021), casting doubts on downstream-focused strategies.

Mining exports also embody a substantial share of services—the global industry of mining-related services was estimated at US$41 billion (Korinek, 2020)—which could constitute a remarkable opportunity for upgrading for developing countries. Services, indeed, represent on average 23% of the value added of world mining exports (Korinek, 2020; Nenci and Quatraro, 2021). Yet, a substantial heterogeneity prevails across countries: in 2016, the service added value in mining exports was barely 12% in Argentina and 16% in Peru, while in Brazil this was as high as 32% (source: OECD TIVA Dataset).

The international trade in mining services is remarkably high, although, worldwide services are largely supplied locally—on average 18% out of the 23% of added value in mining exports. This is not altogether surprising, as many services required in the industry—for instance, construction, or housing—are less traded than goods and/or can only be provided domestically. However, the largest providers of traded services to the mining sector are developed economies, many of them also home to top providers of mining equipment, such as the US and Japan. The US leads, followed by China, Germany, the UK, Japan, France, and the Netherlands (Korinek, 2020). None of the top global mining service providers is from Latin America, and three (Chile, Brazil, and Peru) are among the top six importers. One particular segment—professional, scientific, and technical services—has a much higher probability of being imported, probably reflecting the superior and higher quality technologies from sophisticated equipment providers in advanced countries.7

3. Trends in innovation and knowledge creation in mining

Traditional debate on the knowledge and innovation of extractive activities has long identified several key common features: first, much of innovative and knowledge generating activities lay in the process and product providers (Pavitt, 1984; Kaplan, 2012; Stubrin, 2017; Pietrobelli et al., 2018; Calzada Olvera, 2022); second, innovations are often highly contextualized and difficult to scale up (Stubrin, 2017; Molina, 2018; Calzada Olvera and Iizuka, 2022); third, major technological changes in this sector require a long time due to the large and expensive infrastructure, rigid supplier-client relationship, and multiple actors involved (Scott-Kemmis, 2013; Tilton, 2014); lastly, although innovations are often generated to meet challenges in a highly applied manner, investments in R&D, human resources, technological capabilities, and research institutions remain highly relevant for improving the overall sectoral productivity (Upstill and Hall, 2006; Urzúa, 2011; Ville and Wicken, 2013; Bravo-Ortega and Muñoz, 2015).

Be that as it may, large original equipment manufacturers, multinational mining firms, and EPC/EPCM firms from developed countries constitute a triad that dominates both international and local markets, in most extractive countries as well as in the three countries of this study (with the exception of Brazil’s Vale). Equipment manufacturers dominate the innovation pattern of the sector, and although mining firms themselves invest relatively little in R&D, when technology acquired out of the firm is considered, the sector ranks remarkably well in terms of innovativeness.8 The growing innovativeness of the sector is confirmed as we observe that mining represents a growing share of total world patent families (Figure 2).

The share of mining in total world patent families is growing, 1980–2014.

However, the locus of innovation is mainly far from the locus of mineral extraction. Indeed, the largest mining producers are not home to most patents that are registered mainly in advanced countries (Daly et al., 2022). This is consistent with the fact that the innovative suppliers of METS are primarily based in developed countries (Bamber et al., 2022).

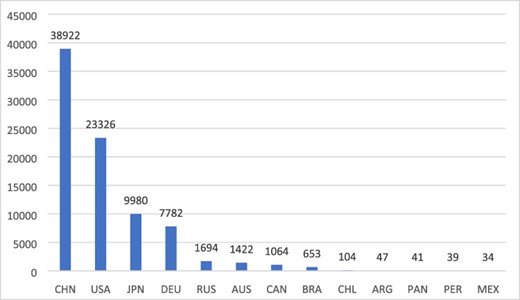

The world mining patents classified by the World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO) are dominated by the US, Germany, Japan, Russia, and more recently by the remarkable ascent of China, reflecting how the pattern of knowledge creation in mining is often far from upstream mining exploration activities. Where is Latin America in this global pattern of mining-related knowledge production? Figure 3 shows the number of unique patents applications filed from 1975 and 2015 in selected countries, indicating the marginal contributions from the region and from the three specific countries of this study.

Total number of mining patent applications in selected countries (1976–2015).

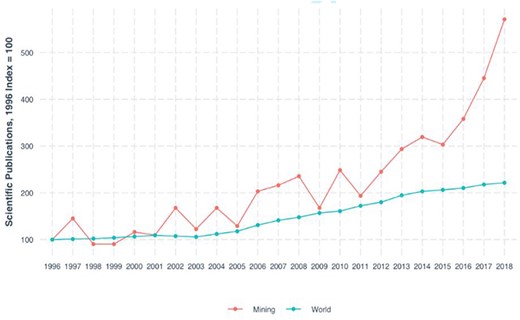

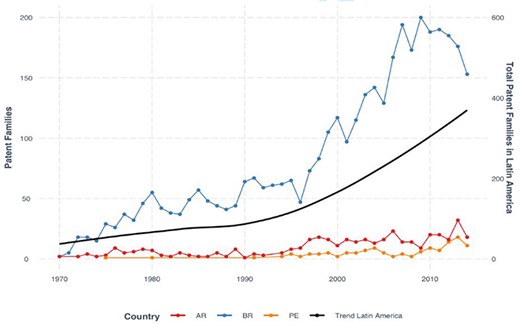

The increase in mining-related scientific knowledge observed above is also reflected in scientific publications, where mining is expanding its share of total publications (Figure 4). The sector is showing a relatively faster innovativeness than other sectors also in our three countries—with a similar pattern confirmed for the whole of Latin America—as the share of mining patents over total patents has been growing significantly during the last two decades (Figure 5). Brazil is the source of more than half of total mining patents in Latin America, yet Argentina and Peru do not patent relevant shares and lag remarkably behind Chile and Mexico (Nenci and Quatraro, 2021, and Figure 6). However, this is likely to reflect the well-known overall pattern of low technological dynamism and relatively weak innovation systems in these countries.

World mining-related scientific publications rise faster than total publications (1998–2018, 1996 = 100).

Share of mining patent families out of total patent families in Brazil, Argentina, and Peru.

Number of patent families in mining technologies: Brazil, Argentina, and Peru (left axis) and Latin America (total trend line, right axis).

In sum, what do we learn from the evidence presented so far on these three Latin American countries? They are all countries with large potential in extractive industries. Brazil and Peru have already been exploiting such potential for years, whilst Argentina has been often pondering whether to deepen this specialization or not, with remarkable differences among its provinces. The role of knowledge and innovation in the sector has remarkably increased worldwide, and Latin America has followed suit, though with a remarkable lag. Clearly, innovation is scattered along the various dimensions of the industry, also reflecting a division of labor among tasks in the value chain. The potential for Latin American countries and their suppliers to engage and capture value from these productions also depends on the innovation and capabilities they develop over time. Moreover, what matters is not only where mining-related innovation is generated, but also how innovation is imported from elsewhere and utilized. Latin American countries tend to be good importers and utilizers of foreign-generated technologies and innovation, and in principle this could contribute to raise their innovation capacity.

In the following section, based on country case-studies, we discuss the remarkable challenges and barriers to entry and upgrade that local suppliers still face, and the opportunities that some of them started exploiting.

4. The role of suppliers in mining GVCs: challenges of entry and upgrading

4.1 Entering the value chain: barriers and success factors

Procurement in the mining sector represents a noteworthy source of spending in both goods and services. In 2018, domestic procurement, i.e., services and inputs provided by all domestic sectors to the mining industry, was equivalent to US$1.4 billion in Argentina, US$16.0 billion in Brazil, and US$5.3 billion in Peru (OECD.Stat., 2021).

However, overall local suppliers face remarkable barriers to entry, and barriers vary in different layers of the GVC. Peruvian suppliers are present in a wide range of activities in many stages of the GVC, but the volumes involved and their share in the industry are still limited, with no strong area of focus. Most products and services are standardized, with limited impact on value added. The strongest presence of local suppliers is in services, metallic structures, consumables, and some niche capital equipment, where factors contributing to success are proximity to the client that allows some customization, and lower logistic costs for inputs being voluminous with high shipping costs (Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021). Moreover, successful suppliers managed to offer flexibility and strong local knowledge to meet special geological conditions and local demand niches that are not catered by the mass market.

Research has shown how mining firms are conservative in terms of strategic inputs procurement (Pietrobelli et al., 2018). The local procurement patterns in Peru reflect those of the global industry, as the sector is dominated by large MNCs. The prevailing principles are quality, safety, and reliability, with compliance with environmental standards becoming relevant only in more recent years. Buyers’ absolute imperative is to minimize risks and costs in their procurement choices, and this results in their notorious preference for the higher capabilities and quality of known manufacturers. Therefore, inputs with high risks and costs are typically procured using long-term (3–5 years) purchasing strategies, and bought from reliable, experienced, and often global suppliers. In any case, providers need to be approved and registered on internal procurement platforms to bid on new contracts and decisions are often made in Lima or abroad (Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021). Willingness to customize solutions to local demands may marginally raise the chance of success and overcome the high barriers. In the case of Brazil, due to the long-term efforts to transfer technology from abroad and adapt it to the local conditions through many policies since the 1960s, some sizable METS work with mining firms; however, much of their efforts are made in importing technologies from abroad, and this occurs through non-resident METS (subsidiaries of multinationals) acting as technology intermediaries for resident METS. This would confirm the overall conservative features and underdeveloped nature of most Brazilian METS (Blundi et al., 2019).

Noticeable areas of weakness in most suppliers are their limited scale, organizational skills, poor standards compliance, and limited access to qualified human capital. Examples of institutions focusing on training relevant for the industry also exist, but they are rather isolated (e.g., UTEC in 2011 and TECSUP in 1984 in Peru). The training efforts of the private sector are equally not-concerted and lack public support.

In several instances, these barriers also operate in highly competitive low-cost categories, where miners prefer to buy from familiar suppliers in their home countries (Bamber et al., 2022).9 Also in these cases there are often stringent safety, environmental, financial, and operational requirements to pre-qualify and enter mining roasters of suppliers. These obstacles are compounded by the very large power asymmetries prevailing in the value chain, which add to the significant barriers to entry (Pietrobelli et al., 2018).

In sum, the demand of procurement of lead-firms in Peru is not (yet) a noticeable opportunity for local suppliers. Barriers are still high, and miners tend to make little effort to develop their portfolio of suppliers, they do not prioritize the provision of technical assistance beyond product requirement and standards; and they do not disseminate information about procurement opportunities. In other words, the quality of linkages tends to be low and mainly with arm-length relationships; moreover, more capable suppliers rarely manage to reduce these asymmetries and improve the quality of linkages through longer term relationships.

Entering the mining value chain proves challenging for domestic firms also in Argentina for two main reasons (Marin et al., 2021). First, mining companies are large, global, mostly foreign, and procure global contracts through their network of well-established global providers. They especially fear risks of failure and interruption of mineral extraction, to the extent that they are open to pay higher costs and lower efficiency for proven solutions. Second, also the first tier of suppliers includes few global firms that are equally risk-averse and protective. They typically set prices and use non-competitive practices, such as the codification of machinery parts that is done and frequently changed by global suppliers.10 This discourages local firms to replace parts otherwise imported and is considered a clear practice to limit competition.

In some instances, however, successful entry was achieved because of the timely responses to sudden requirements by proximate mining companies. Most of the service providers interviewed in the Argentina case-study (Marin et al., 2021) entered the value chain almost exclusively by being close to the operations, despite providing a relatively standard service (e.g., drilling or machinery repair), and offering adaptations to local conditions. The opportunity offered by being close and flexible was multiplied in times of operational crisis, requiring emergency responses.

Sometimes successful entry was also obtained thanks to the reputation gained in other sectors. Argentina has had a strong metalworking sector for many decades with firms specialized in several subsectors: examples were detected of firms that used such previous experience in other related sectors to supply large mining companies.

In Brazil, the situation appears only marginally different. Brazil has had decades of mining activity that made possible the development of several layers of suppliers, also in stages of the value chain requiring high investments in machinery and equipment. However, despite several examples of innovative local suppliers, the evidence reveals that lead firms often prefer established foreign providers (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021). An arms’ length type of GVC governance sometimes emerges, potentially offering a promising ground for collaboration, but the geographical distance of suppliers, which are frequently located in industrial centers far from their clients is still large, hindering the search for joint solutions or for local suppliers to develop more innovative projects. Main clients do not typically provide technical or financial assistance to their providers, though sometimes certify processes and test technical specifications. However, a power imbalance hindering innovation has been detected, where suppliers know they have little negotiating power with their clients to retain any control over innovations and often limited chance to trade with others.

4.2 Asymmetric information and power imbalances

All the case studies analyzed reveal that all suppliers face a problem of asymmetric information with their mining clients. Mining companies do not know about the suppliers, their level of capability, or the kind of products or services they can develop, and suppliers do not know the needs and specific requirements of mining companies. Established mechanisms to connect suppliers with mining companies do not exist. If suppliers had the chance to test their solutions, this would reduce information asymmetry, but this is hardly the case.

Indeed, no mining company in Argentina has programs, departments, or specific policies to develop local suppliers (Marin et al., 2021: 28). Purchase departments have the objective of minimizing costs and do not have the incentive to develop local suppliers. The only incentives to buy locally respond to the need posed by the social license eventually obtained by the company.

These asymmetries and power imbalances are strengthened by the nature of the contracts in place regulating inter-firm relationships. Arms’ length relations tend to prevail everywhere, with short and flexible contracts. Long-term formal agreements with local suppliers hardly exist, and this poses a big problem to suppliers eventually trying to develop more sophisticated products and services and lacking a reliable and durable planning horizon.

The Argentina case is instructive in this regard. Local firms providing services typically become suppliers by winning tenders, with contracts lasting from weeks to several years. Renewal of the contract is always uncertain. Similarly, local producers of standardized goods become suppliers through purchase orders. These types of contracts establish the maximum amount that the mining firm could purchase from the supplier during a certain period. To avoid sanctions, the supplier must supply the amount the mining company demands anytime. Moreover, purchase orders grant all the rights to mining firms, leaving the latter with no obligation to buy any specific quantity of the specified goods. Clearly, this contract poses problems of financial resources and managerial capabilities to small firms.

In addition, contracts are sometimes signed for tailor-made or specific solutions, when mining companies need a piece of important equipment due to an unexpected breakdown or an emergency and seek local firms for a quick solution. Often such tailor-made specific solutions require the development of complex products or services. However, even in these situations, mining companies do not help with the development of solutions and give finance or technical assistance. All the burden of acquiring the necessary knowledge capabilities and investment (often by reverse engineering) is borne by the suppliers. The procedure thus entails financial risks for the supplier because the mining company is not obliged to purchase the part.

Buyer–supplier relationships typically begin in purchase departments. However, the important achievement is when suppliers start interacting with technical departments, which offers access to relevant technical knowledge and raises the likelihood of supplying higher value goods and services. Entering the mine is the next step towards upgrading, as this allows strengthening personal and professional linkages with the mining company’s technical personnel, discussing technical matters, and exploring additional opportunities of procurement, but this rarely occurs.11

4.3 The role of innovation

Can innovation be the key to conquer a procurement contract? Can it also help the process of suppliers’ upgrading within the value chain? Despite some evidence on the rise of innovative suppliers of goods and services, the size of the phenomenon is still relatively small. Miners are usually not open to new suppliers or to new technical solutions. Entry is rarely the result of technological advances, but mostly related to specific windows of opportunity. These, in turn, relate mostly to the necessity of local adaptations/solutions and, most importantly, location advantages. Local suppliers tend to be more flexible and can provide custom-made solutions for unresolved problems or emergencies that need in situ or customized solutions.

Recent studies on Brazil reveal the existence of some examples of innovative suppliers, but these instances were not generalized. The kind of innovation detected was mainly of the “new to the firm” kind, rarely new to the domestic or the international market (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021). The narratives explaining the success of these companies highlighted the importance of a deep understanding of client demands and specific cultural issues, and capacity to take risks, in an environment that has been typically risk-adverse like in most mining value chains (Pietrobelli et al., 2018). The ability to maintain an open dialogue with the client was also acknowledged to be essential. In the case studies on innovations in environmental engineering, the importance of partnerships with universities was also highlighted, particularly for smaller firms accessing well-trained scientists at a reasonable cost. Brazil has a strong tradition of scientific research applied to the mining sector, though the institutional barriers to make cooperation profitable were often pointed out.

Among the obstacles to innovation are large mining clients’ mistrust of supplier’s expertise and/or commitment to health and safety measures, and their lack of interest when it comes to testing innovative solutions. Furthermore, suppliers also face the difficulty of learning how to price the potential benefits that innovations could bring to the client, the benefits of intangibles, and the overall strategy of marketing such contributions. The only exceptions are typically emergencies requiring immediate response. In addition, the rising requirement of social licenses may represent an additional incentive to search for innovative responses. For example, in Brazil, during the 17th Brazilian Mining Congress, the environment and social license to operate were considered as one of the most important issues to be tackled by the industry, government, and trade associations, together with improving mining productivity (Blundi et al., 2019). The social license agenda puts emphasis on improvements and sustainable behavior in the relationships with communities in the vicinity of operations. Indeed, environmental services and effective negotiations with local communities may become increasingly necessary.

In Peru, new areas of technology and innovation proved essential to address rising environmental and social challenges and win procurement orders in some isolated cases (Bamber et al., 2022). Some larger Peruvian mining suppliers have in-house R&D centers (e.g., Famesa Explosivo, Resemin, and Tumi), and access to multiple external sources of knowledge, such as partnerships with university, research institutes, and foreign suppliers. Some mining research centers were established by public universities in key mining localities, and receive financial support via the mining canon that requires to be spent on R&D in mining regions. Importantly, once suppliers establish a reputation, openness to novelty and information exchange appear to increase and innovation becomes easier (Bamber and Fernandez-Stark, 2021; Marin et al., 2021). However, in general, procurement of new, innovative products and solutions is typically not even considered, if unsolicited. Additionally, once a technology is adopted, the reluctance to make further changes or embrace innovation limits opportunities for new suppliers due to perceived high costs and potential disruptions.

Local suppliers that have managed to enter value chains in Argentina innovate typically through informal mechanisms Exceptional cases of product development “new to the world” were observed. The typical case of success was related to the capabilities to operate existing technologies following standard procedures, or to adapt technologies and have them work better in the local context. Technological efforts mainly consisted of hiring skilled workers and buying new machinery and equipment, with the related embodied knowledge. Certifications were also very important, and a necessary condition for all firms. The interactions with local or international technology and scientific institutions were also rare, very informal, mainly local and unidirectional, i.e., marked by the absence of collaborative research or co-development of new products or processes between such institutions and local suppliers (Marin et al., 2021).

In sum, entering value chains and upgrading within them poses substantial and different challenges to local suppliers. The evidence reveals that, despite the obstacles, some suppliers’ advantages have helped access to value chains in several circumstances. These include proximity to lead mining firms, that offers security, flexibility, quality, and speed of interactions and response; location specificities with each mine being different, demanding tailor-made solutions to specific local problems; the use of new areas of scientific knowledge and technology that open up new opportunities for suppliers, e.g., biotechnology and new materials, ICT, and automation (Pietrobelli and Calzada Olvera, 2018).

Moreover, the quality of linkages with mining firms does not help the development of local suppliers substantially: entry barriers posed by lead firms are high, the contractual arrangements do not favor durable long-term relationships and upgrading, the hierarchical governance of the relationships is confirmed to be an additional obstacle, and remarkable information and power asymmetries remain widespread.

5. The local innovation and regulatory systems

Besides entry barriers related to the practices and the industrial organization of the sector, local firms are also hampered by the three countries’ weaknesses of the local innovation and regulatory systems. Indeed, environmental and social regulations increasingly play a major role in the sector and differ across countries. In this section, we briefly discuss: (i) the central role that regulations play for exploration and exploitation, and for the development of local suppliers at the national and sub-national levels; (ii) and the nature and weaknesses of the local innovation systems, due to the absence of testing and certification facilities, the paucity of research institutions, poor conditions for entrepreneurship, and lack of public support for R&D and innovation.

The legislative setups of government differ significantly in Argentina, Brazil, and Peru. Peru has the most centralized governance system of the three, and the central government holds the most power. In contrast, Argentina has the strongest autonomy of provinces, and provincial governments can enact their own constitutions, freely organize their local governments, and own and manage their natural and financial resources. In Brazil, (Regional) states have semi-autonomous self-governing status with relative financial independence, but the model of administration is set by the Federal constitution. The differences in the authority and autonomy of subnational governments influence the development of mining activities, as well as the possible entry and upgrading of local suppliers.

5.1 Peru

Peru’s policy towards strengthening its backward linkages has been considered overly focused on social and environmental regulations while lacking focus on suppliers’ upgrading and innovation (Bamber et al., 2022). A clear long-term national strategy for this industry is also notably absent. Peru does not apply local contents or procurement targets to the industry (OECD, 2017). Despite many multinational mining firms claim to prioritize local firms and report on their progress to gain social license to operate, foreign suppliers continue to be favored over the local ones.

In the past, the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM) oversaw this sector; however, since 2007, the Agency for Environmental Assessment and Enforcement and the Ministry of Labour are also on board. The strategic orientation towards mining of these three ministries is not well coordinated, with overlapping regulations, excessive bureaucracy, and a high degree of redundancy (Vivoda, 2008). The number of regulations had increased more than 10-fold from 2005 to 2015, from 24 to 242 respectively (Bamber et al., 2022), with the need to obtain permits to operate from the General Directorate of mining (DGM), the General Directorate of Mining Promotion (DGPM), MINEM, Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI), the Ministry of Culture, and other institutions (Tras100d, 2017).

The stringent new regulatory measures are concentrated in the social and environmental dimensions. The newly introduced regulation on environment has long delayed granting of environmental approval certificates or validation of the extension of mining operations.12 Furthermore, despite the efforts made by the government, such as Prior Consultation Law in 2011, that requires prior consultation with indigenous communities before any infrastructural project including mining, it has failed to resolve social conflicts against mining operation in the regions, where most mining operations reside. The importance of getting social license to operate is increasing in Peru (Ernst and Young, 2018). Out of the 975 reported active social conflicts in 2021, 739 (75.8%) were related to mining.13

5.2 Argentina

In Argentina, there is a total of 17 mines, and 70% of them are in only three provinces: Santa Cruz (35%), Catamarca (25%), and San Juan (10%) (INDEC, 2018). The main metals produced are gold, silver, and copper. Institutions and regulations related to mining are implemented by both Federal and provincial governments. Due to the Federal Republic system, mining activity in Argentina at the federal level is overseen by the Secretary (Ministry) of Mining Policy under the Ministry of Production and Labor which regulates mining companies and their investments. The Secretary of Industry is also in charge of supplier development, and a noteworthy example is the PRODEPRO program.14

The sector is regulated at the federal level by the Federal Mining Code, the Mining Investment Law, and the Law for the Environmental Protection and Mining Activities. Although these laws define the roles of federal and provincial governments, in many aspects, the layered regulatory mechanisms are not well coordinated and hamper the development of mining activities. For instance, the Mining Code outlines the rules and procedures for granting, maintaining, transferring, and cancelling mineral rights, through a concession system, and procedures under this code are implemented with provincial regulations (Marin et al., 2021). In principle, provinces hold the ownership over natural resources in their territories, according to the constitutional reform in 1994, and also have the right to authorize exploration and extraction, charge royalties and other non-fiscal contributions, and ensure environmental compliance with the regulatory framework. Each province has its own mining administrative law and provincial mining authorities. Again, these are also differently executed across provinces. To make the matter more complicated, the competent authority on environmental affairs is either the mining authority or the environmental authority depending on how provincial government grants authority (Bastida and Murguía, 2018). In 2010, the National Congress enacted Law 26 639 of minimum standards for Glacier Protection, banning mining from glacier and ‘periglacier’ areas, threatening the expansion of mining activities in the country.

Some attempts have been made to coordinate and harmonize federal and provincial policies and laws to sharpen a competitive strategy, with the new Federal Mining Agreement signed in 2017. These attempts, however, have failed (Marin et al., 2021). The Consejo Federal de Mineria (COFEMIN), an institution in charge of coordinating such policies has been inactive since 1991. In 2012, the provincial governments of several provinces (Jujuy, Salta, Catamarca, La Rioja, San Juan, Mendoza, Neuquén, Rio Negro, Chubut, and Santa Cruz) created a new mining project, called Federal Organization of Mining Provinces (OFEMI) to favor the coordination and harmonization of sectoral regulation as well as the creation of state-owned provincial companies that could participate as partners in new mining projects. As a result, some companies were created but, overall, also this initiative appears to have lost momentum.

Another remarkable area of poor coordination regards local content policies (LCPs), as their implementation can vary across provinces. Under the current provincial legislation, mining firms located in each province are obliged to acquire a certain number of inputs from suppliers that are physically located within the same province. This created competition among provinces and additional entry barriers for potential mining suppliers. For instance, the Oil and Gas Cluster in Cordoba has strong metalworking firms that cannot enter mining value chains in other provinces outside the Cordoba province. The creation of FAPMIN, the Federal Chamber of Mining suppliers, that should coordinate national suppliers and promote joint ventures, has not helped in this regard.

The institutional challenges are not limited to the poor coordination at different government levels but extend to the frequent changes and discontinuity of regulations. Since the 1990s, the laws in Argentina have been shifting back and forth from a mining investment-friendly environment to a restrictive one through export taxes and various duties. In addition, the social acceptance to the mining activity is notably low in Argentina. The metal mining sector in Argentina has been expanding in parallel with growing social conflict since the opening of the first large-scale metal mine in the country (Bajo de la Alumbrera in 1997). Later, social movements began in various provinces (Murguía and Godfrid, 2019), and as a result, 7 out of 23 provinces have legislation in force that bans open-pit mining. This represents a significant challenge for the industry. Only in 2020, estimates suggest that at least 21 mining projects were delayed by social conflicts, amounting to at least US$13 billion of investment (Marin et al., 2021).

5.3 Brazil

Two main government agencies operate in the mining sector in Brazil. One is Secretariat for Geology, mining and mining Transformation (SGM) that is linked to the Ministry of Mines. The responsibility of the latter ministry is to formulate public policy for the mining sector in consultation with the industry. The other agency is the National Agency for Mining (ANM) which is the industry regulator. This agency has more autonomy with regards to the government and has discretionary power over the sector in auditing, applying fines, granting mining licenses and ordering mines to close. However, the Agency is still new—it was established only in 2017—and going through a consolidation process in terms of funding and personnel. The mining legislation constitutes a complex layer of laws and rules at the federal, state and municipal levels, to which mining firms must comply also in Brazil (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021).15

The Brazilian Government made additional changes to the mining sector’s rules with the Provisional Presidential Decree No. 790 on June 25, 2017 (MP 790), that broadened the scope of the federal government’s competences and regulated activities. The regulation now covers the entire life cycle of the mining sector, from prospection and extraction to ore marketing and mine decommissioning. The new rules seek to boost the sector’s dynamics and modernization, and to intensify the country’s mineral production through new investments and new technology. This change came after several changes in regulation. The Brazil’s current Mining Code had been established in 1960 and then updated in 1996. The federal government has been making efforts to implement new rules and make the sector more competitive and attractive to investors by increasing transparency and legal security (Iizuka et al., 2022). For instance, the most recent regulatory regime concerning dam safety (Law No. 23 291 on February 25, 2019) was established by the State of Minas Gerais. This law stipulates that “accretion, final, or temporary disposal of tailings and industrial and mining wastes must be avoided whenever there is a better technique available”. (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021).

The propensity to incorporate innovative activities has been rising gradually in Brazil’s mineral sector. It has been noticed that, between 2003 and 2014, much of Brazilian miners’ innovative technological capabilities was accumulated in partnerships with universities and local research institutes, consultants, and agents along the production chain, suppliers, and clients (Figueiredo and Piana, 2018; 2021). Large networks of research institutes, universities, and technical and technological institutes are located in different parts of the country. Among the centers of excellence are Mining Engineering at Minais Gerais, SENAI institute of Innovation and Mineral Processing, and CETEM, the Centre of Mineral Technology. They conduct collaborative research with firms (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021).

Such institutional collaboration in the mineral sector has strong historical foundations in Brazil. The sectoral innovation system was formed through a long process of technological and scientific skills building and accumulation, involving feedback and interaction among companies, research institutions, and universities. It is not by chance that undergraduate and postgraduate courses in Mining Engineering, Materials Engineering, and Metallurgy have flourished and are well established at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) (Suzigan et al., 2008). Such collaboration has been achieved incrementally, as some confidentiality and intellectual property issues are yet to be resolved to smooth out such relations. Vale S.A. exemplifies the way in which such obstacles can be overcome with proper R&D investments. Vale has broadened its portfolio of academic partners since 2010, by issuing calls for proposals for partnership with governmental science promotion agencies and has thus gained access to a broad spectrum of research groups that were previously unknown to the company (Mello and Sepúlveda, 2017).

Overall, the mining industry in Brazil appears to have a denser institutional support network targeting the creation of the right conditions for the industry to flourish than the two other countries; however, the high instability of governments has often disrupted the steady development of the sector and of its local suppliers (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021). In addition, also the weakness of the local resident METS had been revealed by the high proportion of direct and indirect (via non-resident METS) imports of technology (Blundi et al., 2019).

6. Conclusions and policy implications

In this paper, we have shown with new empirical evidence how production is organized along value chains, and how Latin America is mainly participating in the upstream stages of the value chain. This may be explained by market trends making it less convenient to move to downstream activities such as refining and smelting, where competition is harsh with a notable presence of Chinese companies.16 We have also confirmed that the sector is proving highly innovative, with growing patenting and scientific publications relevant to the sector.

Whilst this could offer new opportunities to local suppliers that are different from the past (Pietrobelli et al., 2018), recent evidence is showing that entering and upgrading within mining value chains is proving extremely difficult to local suppliers from Latin America. The successes recorded are few and isolated, and entering a value chain provides no guarantee to achieve upgrading due poor contractual arrangements, hierarchical modes of governance, little support from the local regulatory, and innovation systems.

Is the future likely to offer new and different opportunities? All studies converge in the indication that there is a need to address the procurement practices of mining firms and international OEMs, aimed at improving the quality and stability of linkages between local firms and value chain leaders. Governments should try to break unfair or conservative procurement practices, by incentivizing transparency on supply opportunities and active supplier development programs, and by demanding wider participation of local firms in procurement policies. However, local content policies must be used carefully, avoiding unrealistic goals that create inefficiencies and foster opportunistic behavior of local suppliers, and should eventually come with appropriate efforts to develop capabilities (Anzolin and Pietrobelli, 2021).

The choice between “defensive” vs. more active regulations oriented to productive and supplier development is still open. In Peru, for instance, all the focus remains on regulation, and no concerted effort exists to promote industrial development. Argentina, at the opposite extreme, has a decentralized system that greatly relies on provincial governments. For example, local content policies were created at the provincial level, creating barriers for Argentinian firms from other provinces. Brazil has a potentially important but still underfunded National Mining Agency (ANM) that has not functioned effectively yet.

Some dimensions are clearly emerging and will condition future developments in the sector in these countries (Casaburi and Pietrobelli, 2022). Thus, the demand for environmentally sustainable mining activities is rising fast worldwide and will soon become a necessary condition. Environmental impact and conflicts have been dominating the sector recently. With the energy transition needing more minerals, many could be high-carbon emission minerals that will require appropriate technologies to limit their environmental impact. The environmental disasters recorded in recent years (Navas-Aleman and Bazan, 2021) are not acceptable anymore. The plans to “decarbonize” the mining activity are increasingly pressuring mining companies, and this will shape and define the future for all mining producers. A positive development has been recorded with the fast growth of patents and technologies to deal with the rising environmental challenges like the treatment of wastewater, the biological treatment of soil, the waste disposal, and the environmental technologies related to mineral and to metal processing. This is an area of crucial importance to local communities, where the mining extraction and refining take place. Suppliers capable of offering such solutions, and complying with these environmental requirements, will enjoy a remarkable competitive edge. In this regard, the role of mining services is clearly an issue that will deserve future research.

In addition, the mine of the future will need to respect all the conditions of social sustainability. Local and national communities are reacting strongly to the threats to their social and natural environments and gained substantial awareness and capacity to react. For example, already in 2018, Chile’s federation of large mining companies (Consejo Minero) had acknowledged that the “social license” was considered by 43% of its member companies the most critical aspect of the mining production, far above other aspects. They also highlighted how the most strategic objective would be the construction of trust and confidence in the relationships between mining companies and the local communities (Consejo Minero, 2018). The design and implementation of practices complying with the “social license” offers opportunities to local suppliers.

The experiences of other countries suggest that a greater effectiveness in reducing disputes over natural resources is the creation of processes and institutions that involve civil society both in making decisions about where and how to carry out mining activity, and in monitoring activities. This approach appears fairer and potentially transformative but will require a strong decision of the state to get involved and lead the process, with innovative approaches.

Footnotes

Although the following analysis focuses on copper value chains, most of their characteristics are shared also by most metal and extractive industries.

This study does not focus on the role of EPC/EPCM firms in the three countries, although we acknowledge that they may play a relevant influence on suppliers’ entry.

Trade data illustrates the differences in processing capacities across these countries. Based on data from the World Integrated Trade Solution and the Observatory of Economic Complexity, in 2021 Peru’s exports of copper cathodes—a high-purity processed form of copper (HS code: 740 311)—were equivalent to US$2289 million, representing approximately 2.72% of global exports of this product. In contrast, Brazil’s exports of copper cathodes in the same year were valued at US$247 million, accounting for a mere 0.29% of global exports. Argentina did not register any exports of this product. Additionally, in the same year, gross exports of other forms of processed copper, such as billets (HS code: 740 313), were only reported by Brazil, with export value equivalent to approximately US$29.40 thousand—representing a marginal share of global exports (0.026%).

These products are: HS 260 300 (copper ore and concentrate); 7402 (unrefined copper, copper anodes for electrolysis), and 740 311 (copper cathodes).

While Chile and Peru have faced serious environmental and health issues related to tailings, disasters of this sort stand out in Brazil: The 2019 Vale’s tailings dam failure in Brumadinho, the worst in the country’s history, which occurred three years after another mining accident in Mariana in 2015, both resulting in significant losses of life and extensive environmental damage.

The exception here is Indonesia which also acts mainly as an exporter of unrefined copper, while Chile, Australia, and Canada still obtain at least one third of their copper export revenues from the refined product.

Based on OECD.Stat. (2018) data, i.e., the share of value added by type of service in total services, the top providers of mining-related professional, scientific, and technical services, ranked in descending order, are: the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States, France and Germany.

This is calculated as the ratio of R&D in intermediate goods and services to internal R&D/sales (Upstill and Hall, 2006).

Cochilco (2016), for example, identifies six critical supplies for the copper mining industry: Quicklime, grinding balls, extraction trucks, shovel loaders, off-road tires, and flocculants. In each of these cases, in the Chilean market, the three leading suppliers account for over 75% of the market.

See the experience of Minexus, a private initiative to solve the problem of asymmetric information between lead firms and suppliers by reading and decoding all heavy machinery parts and disseminating this information to local suppliers (Marin et al., 2021).

Marin et al. (2021) illustrate the case of metalworking firm Jaime and ICT company Minetech as success and failure cases, respectively, of upgrading in this way in Argentina.

https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=161334bb-4087-4d76-ab72-6d6999a91e11 accessed February 22, 2023.

Fitch and office of Ombusdman, 2022, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/corporate-finance/social-conflicts-regulation-curb-perus-mining-sectors-growth-13-04-2022, accessed February 15, 2023.

https://www.argentina.gob.ar/acceder-al-programa-de-desarrollo-de-proveedores, accessed February 22, 2023.

Other powerful non-state actors are the Instituto Brasileiro de Mineracao (IBRAM) representing all firms from the sector, and ABCobre (Associaciao Brasileira do Cobre) that is the entity focusing on copper and promoting its production and consumption.

Heightened geopolitical tensions and new trends in the architecture of global value chains (e.g., nearshoring) can contribute to change these trends, although their impacts remain are still unclear to this date.

References

Author notes

Preliminary drafts of the research were presented at seminars for IADB Regional Policy Dialogue meetings, Globelics 2021, SASE 2021, GRIPS, Tokyo, 2020, and Catchain, Milan, 2020. We thank participants and two anonymous referees for their many useful questions and discussions, and Gabriel Casaburi for his constant support. The research was partly financed by the Interamerican Development Bank (IADB) and UNU-MERIT project “Innovation and Competitiveness in Mining Value Chains”. The authors have no conflict of interests with the funding organizations. All statements expressed here and possible mistakes are only the responsibility of the authors and not of their respective organizations.