-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ruby Greywoode, Francesca Petralia, Thomas A Ullman, Jean Frederic Colombel, Ryan C Ungaro, Racial Difference in Efficacy of Golimumab in Ulcerative Colitis, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 29, Issue 6, June 2023, Pages 843–849, https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac161

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Observational studies have described racial differences in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) genetics, clinical manifestations, and outcomes. Whether race impacts response to biologics in IBD is unclear. We conducted a post hoc analysis of phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials in ulcerative colitis to evaluate the effect of race on response to golimumab.

We analyzed pooled individual-level data from induction and maintenance trials of golimumab through the Yale Open Data Access Project. The primary outcome was clinical response. Secondary outcomes were clinical remission and endoscopic healing. Multivariable logistic regression was performed comparing White vs racial minority groups (Asian, Black, or other race), adjusting for potential confounders.

There were 1006 participants in the induction (18% racial minority) and 783 participants in the maintenance (17% racial minority) trials. Compared with White participants, participants from racial minority groups had significantly lower clinical response (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28-0.66), clinical remission (aOR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.22-0.77), and endoscopic healing (aOR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.31-0.74) at week 6. Participants from racial minority groups also had significantly lower clinical remission (aOR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.28-0.74) and endoscopic healing (aOR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.96) at week 30. There were no racial differences in placebo response rates.

Ulcerative colitis participants from racial minority groups were less likely to achieve clinical response, clinical remission, and endoscopic healing with golimumab compared with White participants in induction and maintenance trials. Further studies are needed to understand the impact of race on therapeutic response in IBD.

Lay Summary

Racial disparities exist in inflammatory bowel disease, but the influence of race on response to biologic therapy is unclear. In pooled analysis of golimumab clinical trials, participants from racial minority groups were less likely to achieve clinical efficacy compared with White participants.

Racial differences exist in inflammatory bowel disease outcomes.

The influence of race on response to biologic therapy is not well defined.

Participants from racial minority groups with ulcerative colitis were less likely to achieve clinical response, clinical remission, and endoscopic healing in golimumab clinical trials compared with White participants.

Race is a potential factor in assessing clinical efficacy of biologic therapy in ulcerative colitis.

Introduction

Race, ethnicity, and ancestry are increasingly recognized as important factors in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) genetics, clinical phenotypes, and outcomes.1-4 Research in IBD genetics has led to the discovery of ancestry-specific risk loci as well as differential effect sizes and allele frequencies between divergent ancestral populations.5-8 Observational studies have also described racial variation in clinical manifestations and disparities in health-related outcomes.9-12 For example, Black patients have higher rates of perianal and penetrating Crohn’s disease and are more likely to experience disease related complications compared with White patients even with similar tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonist use in a North American cohort.13 IBD is increasingly recognized in diverse populations around the globe.3,14,15 Differences in outcomes by race are often attributed to social factors, such as timely and reliable access to health care.10,12,13 However, data are lacking on whether race influences therapeutic efficacy of medications in IBD. Although race has inherent limitations in accounting for biologic differences,16 racial background has been found in various disease states to be a useful marker of potential response to drug therapy.17,18 For instance, a strong association between the NUDT15 R139C polymorphism and thiopurine-induced leukopenia has been observed in Asian populations.19 To evaluate whether race affects response to TNF antagonists, we conducted a post hoc analysis of participant-level data from phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials in IBD.

Methods

Data Source

Induction and maintenance trials of TNF antagonists in adults with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease were accessed through the Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project. The YODA Project is a public data-sharing collaborative that provides access to de-identified clinical trial data from Johnson and Johnson coordinated through Yale University. Only pharmaceutical products from Johnson and Johnson are available in the database. Products (eg, adalimumab) from other pharmaceutical companies are not part of the database. After review and approval of our research proposal (#2018-3556), the YODA scientific committee granted access to Johnson and Johnson TNF antagonist trials: for infliximab, A Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-Term Treatment Regimen (ACCENT-I) (NCT00207662), A Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-Term Treatment Regimen in Patients with Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease (ACCENT-II) (NCT00207766), Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 1 (ACT-1) (NCT00036439), and ACT-2 (NCT00096655) trials; and for golimumab, the Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment Subcutaneous (PURSUIT-SC) (NCT00487539) and Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment Maintenance (PURSUIT-M) (NCT00488631) trials. The total number of participants from racial minority groups in each of the infliximab trials was low (around 5% of total) and deemed insufficient to perform meaningful analysis. We chose to limit the analysis to trials of golimumab in UC to avoid increasing heterogeneity (by including different IBD subtypes and medication types) with minimal increase in sample size from infliximab trials. Therefore, only participants from the golimumab induction (NCT00487539) and maintenance (NCT00488631) trials were analyzed in this study (see Results).

Racial Categories

Race was categorized according to participants’ clinical trial designation: Asian, Black, Caucasian, or other race. In the current study, any participant identified as Caucasian was considered to be White. Data on Hispanic ethnicity were not available. No further racial or ethnic information about those with other race was available. Race was analyzed as White vs racial minority (combination of Asian, Black, and other race designation). Owing to small subgroup numbers, it was not possible to provide race-specific responses for Black and other race groups separately. Subgroup analysis of Asian participants was performed.

Outcomes

In the induction golimumab trial (NCT00487539), the primary endpoint was clinical response at week 6. In the maintenance trial (NCT00488631), the primary outcome was maintenance of clinical response at week 54. Clinical response in both trials was defined as a decrease from baseline Mayo score ≥30% and >3 points, with either a rectal bleeding subscore of 0 or 1 or a decrease from baseline in rectal bleeding subscore ≥1. Secondary outcomes in both trials were clinical remission, defined as a Mayo score ≤2 points with no subscore >1, and endoscopic healing, defined as a Mayo endoscopy subscore of 0 or 1.

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants from White and racial minority groups using chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. We conducted multivariable logistic regression to study the independent association of race with each outcome in the treatment and placebo arms of both trials after adjusting a priori for potential confounders: age, sex, induction dose, baseline total Mayo score, and immunomodulator and corticosteroid use. Data on participants’ disease duration were not available. The maintenance trial analysis consisted of participants from the PURSUIT-SC trial who were followed beyond induction to 54 weeks of maintenance treatment. Participants who received only placebo were included in the placebo group. Participants who initially received placebo and then later received golimumab were excluded. Outcomes were assessed at the end of induction (week 6) and during maintenance (at weeks 30 and 54). P < .05 was considered statistically significant. R software version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for all analyses.20

Ethical Considerations

This study used de-identified secondary data and received an exemption from full board review by the Einstein-Montefiore Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of the 6 TNF antagonist trials initially screened, 4 were infliximab trials that included few participants from racial minority groups (Table 1). The total percentage of participants from racial minority groups in each of the infliximab trials ranged from 4% to 7%. The 2 golimumab trials had percentages of participants from racial minority groups of approximately 18%. Because the number of participants from racial minority groups in the infliximab trials was low, only participants from the golimumab trials were included in this pooled analysis.

Racial distribution of tumor necrosis factor antagonist clinical trials screened for inclusion in pooled analysis

| Trial Name . | Total Participants (% White) . | Racial Minority Participants (% Total) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian . | Black . | Other . | ||

| ACCENT-I (NCT00207662) | 573 (95.8) | 5 (0.9) | 12 (2.1) | 7 (1.2) |

| ACCENT-II (NCT00207766) | 306 (95.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (0.65) |

| ACT-1 (NCT00036439) | 364 (93.4) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) | 14(3.8) |

| ACT-2 (NCT00096655) | 364 (94.5) | 5 (1.4) | 8 (2.2) | 7 (1.9) |

| PURSUIT-SC (NCT00487539) | 1065 (82.1) | 126 (11.8) | 27 (2.5) | 38 (3.6) |

| PURSUIT-M (NCT00488631) | 1228 (82.4) | 151 (12.3) | 25 (2.0) | 40 (3.3) |

| Trial Name . | Total Participants (% White) . | Racial Minority Participants (% Total) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian . | Black . | Other . | ||

| ACCENT-I (NCT00207662) | 573 (95.8) | 5 (0.9) | 12 (2.1) | 7 (1.2) |

| ACCENT-II (NCT00207766) | 306 (95.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (0.65) |

| ACT-1 (NCT00036439) | 364 (93.4) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) | 14(3.8) |

| ACT-2 (NCT00096655) | 364 (94.5) | 5 (1.4) | 8 (2.2) | 7 (1.9) |

| PURSUIT-SC (NCT00487539) | 1065 (82.1) | 126 (11.8) | 27 (2.5) | 38 (3.6) |

| PURSUIT-M (NCT00488631) | 1228 (82.4) | 151 (12.3) | 25 (2.0) | 40 (3.3) |

Abbreviations: ACCENT-I, A Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-Term Treatment Regimen; ACCENT-II, A Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-Term Treatment Regimen in Patients with Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease; ACT-1, Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 1; ACT-2, Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 2; PURSUIT-M, Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment Maintenance; PURSUIT-SC, Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment Subcutaneous.

Racial distribution of tumor necrosis factor antagonist clinical trials screened for inclusion in pooled analysis

| Trial Name . | Total Participants (% White) . | Racial Minority Participants (% Total) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian . | Black . | Other . | ||

| ACCENT-I (NCT00207662) | 573 (95.8) | 5 (0.9) | 12 (2.1) | 7 (1.2) |

| ACCENT-II (NCT00207766) | 306 (95.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (0.65) |

| ACT-1 (NCT00036439) | 364 (93.4) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) | 14(3.8) |

| ACT-2 (NCT00096655) | 364 (94.5) | 5 (1.4) | 8 (2.2) | 7 (1.9) |

| PURSUIT-SC (NCT00487539) | 1065 (82.1) | 126 (11.8) | 27 (2.5) | 38 (3.6) |

| PURSUIT-M (NCT00488631) | 1228 (82.4) | 151 (12.3) | 25 (2.0) | 40 (3.3) |

| Trial Name . | Total Participants (% White) . | Racial Minority Participants (% Total) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian . | Black . | Other . | ||

| ACCENT-I (NCT00207662) | 573 (95.8) | 5 (0.9) | 12 (2.1) | 7 (1.2) |

| ACCENT-II (NCT00207766) | 306 (95.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (0.65) |

| ACT-1 (NCT00036439) | 364 (93.4) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) | 14(3.8) |

| ACT-2 (NCT00096655) | 364 (94.5) | 5 (1.4) | 8 (2.2) | 7 (1.9) |

| PURSUIT-SC (NCT00487539) | 1065 (82.1) | 126 (11.8) | 27 (2.5) | 38 (3.6) |

| PURSUIT-M (NCT00488631) | 1228 (82.4) | 151 (12.3) | 25 (2.0) | 40 (3.3) |

Abbreviations: ACCENT-I, A Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-Term Treatment Regimen; ACCENT-II, A Crohn's Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-Term Treatment Regimen in Patients with Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease; ACT-1, Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 1; ACT-2, Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 2; PURSUIT-M, Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment Maintenance; PURSUIT-SC, Program of Ulcerative Colitis Research Studies Utilizing an Investigational Treatment Subcutaneous.

A total of 1006 participants (18% racial minority) were included from the golimumab induction trial (NCT00487539) and 783 participants (17% racial minority) from the golimumab maintenance trial (NCT00488631). Baseline characteristics between participants from White and racial minority groups were similar except for more White participants on corticosteroids at baseline in the placebo group (Table 2). The mean age was 40 years, and 40% of participants were women. Most participants from racial minority groups were Asian in both the induction (Asian 66%, Black 14%, other 20%) and maintenance (Asian 70%, Black 12%, other 19%) trials.

Baseline characteristics of participants in included golimumab clinical trials

| . | Golimumab . | Placebo . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | |

| Induction | ||||||

| n | 117 | 583 | 65 | 241 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 73 (62.39) | – | – | 48 (73.85) | – | – |

| Black | 16 (13.67) | – | – | 9 (13.84) | – | – |

| Other | 28 (23.93) | – | – | 8 (12.30) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.99 ± 13.64 | 39.02 ± 12.39 | .13 | 39.13 ± 12.63 | 38.91 ± 13.30 | .91 |

| Female | 48 (41.03) | 251 (43.05) | .76 | 26 (40.00) | 119 (49.38) | .21 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (39.32) | 177 (30.36) | .07 | 25 (38.46) | 67 (27.80) | .13 |

| Corticosteroids | 27 (23.08) | 186 (31.90) | .06 | 8 (12.31) | 76 (31.53) | <.01 |

| Mayo score | 8.53 ± 1.60 | 8.53 ± 1.51 | .99 | 8.28 ± 1.34 | 8.30 ± 1.42 | .89 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 7 (5.98) | 59 (10.12) | .40 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 56 (47.86) | 261 (44.77) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 54 (46.15) | 263 (45.11) | – | – | – | – |

| Maintenance (week 30) | ||||||

| n | 122 | 613 | 9 | 39 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 87 (71.31) | – | – | 7 (77) | – | – |

| Black | 13 (10.66) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Other | 22 (18.03) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.45 ± 13.13 | 38.04 ± 12.37 | .06 | 38.67 ± 12.43 | 40.78 ± 14.39 | .69 |

| Female | 50 (40.98) | 259 (42.25) | .84 | 6 (66.67) | 20 (51.28) | .47 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (37.71) | 197 (32.14) | .24 | 2 (22.22) | 11 (28.20) | 1.00 |

| Corticosteroids | 47 (37.70) | 298 (48.61) | .05 | 2 (22.22) | 20 (51.28) | .15 |

| Mayo score | 6.25 ± 2.42 | 5.08 ± 2.84 | <.01 | 3.67 ± 2.06 | 2.95 ± 1.67 | .35 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 6 (4.92) | 43 (7.01) | .06 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 113 (92.62) | 523 (85.32) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 3 (2.46) | 47 (7.67) | – | – | – | – |

| . | Golimumab . | Placebo . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | |

| Induction | ||||||

| n | 117 | 583 | 65 | 241 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 73 (62.39) | – | – | 48 (73.85) | – | – |

| Black | 16 (13.67) | – | – | 9 (13.84) | – | – |

| Other | 28 (23.93) | – | – | 8 (12.30) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.99 ± 13.64 | 39.02 ± 12.39 | .13 | 39.13 ± 12.63 | 38.91 ± 13.30 | .91 |

| Female | 48 (41.03) | 251 (43.05) | .76 | 26 (40.00) | 119 (49.38) | .21 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (39.32) | 177 (30.36) | .07 | 25 (38.46) | 67 (27.80) | .13 |

| Corticosteroids | 27 (23.08) | 186 (31.90) | .06 | 8 (12.31) | 76 (31.53) | <.01 |

| Mayo score | 8.53 ± 1.60 | 8.53 ± 1.51 | .99 | 8.28 ± 1.34 | 8.30 ± 1.42 | .89 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 7 (5.98) | 59 (10.12) | .40 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 56 (47.86) | 261 (44.77) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 54 (46.15) | 263 (45.11) | – | – | – | – |

| Maintenance (week 30) | ||||||

| n | 122 | 613 | 9 | 39 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 87 (71.31) | – | – | 7 (77) | – | – |

| Black | 13 (10.66) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Other | 22 (18.03) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.45 ± 13.13 | 38.04 ± 12.37 | .06 | 38.67 ± 12.43 | 40.78 ± 14.39 | .69 |

| Female | 50 (40.98) | 259 (42.25) | .84 | 6 (66.67) | 20 (51.28) | .47 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (37.71) | 197 (32.14) | .24 | 2 (22.22) | 11 (28.20) | 1.00 |

| Corticosteroids | 47 (37.70) | 298 (48.61) | .05 | 2 (22.22) | 20 (51.28) | .15 |

| Mayo score | 6.25 ± 2.42 | 5.08 ± 2.84 | <.01 | 3.67 ± 2.06 | 2.95 ± 1.67 | .35 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 6 (4.92) | 43 (7.01) | .06 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 113 (92.62) | 523 (85.32) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 3 (2.46) | 47 (7.67) | – | – | – | – |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated.

Baseline characteristics of participants in included golimumab clinical trials

| . | Golimumab . | Placebo . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | |

| Induction | ||||||

| n | 117 | 583 | 65 | 241 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 73 (62.39) | – | – | 48 (73.85) | – | – |

| Black | 16 (13.67) | – | – | 9 (13.84) | – | – |

| Other | 28 (23.93) | – | – | 8 (12.30) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.99 ± 13.64 | 39.02 ± 12.39 | .13 | 39.13 ± 12.63 | 38.91 ± 13.30 | .91 |

| Female | 48 (41.03) | 251 (43.05) | .76 | 26 (40.00) | 119 (49.38) | .21 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (39.32) | 177 (30.36) | .07 | 25 (38.46) | 67 (27.80) | .13 |

| Corticosteroids | 27 (23.08) | 186 (31.90) | .06 | 8 (12.31) | 76 (31.53) | <.01 |

| Mayo score | 8.53 ± 1.60 | 8.53 ± 1.51 | .99 | 8.28 ± 1.34 | 8.30 ± 1.42 | .89 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 7 (5.98) | 59 (10.12) | .40 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 56 (47.86) | 261 (44.77) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 54 (46.15) | 263 (45.11) | – | – | – | – |

| Maintenance (week 30) | ||||||

| n | 122 | 613 | 9 | 39 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 87 (71.31) | – | – | 7 (77) | – | – |

| Black | 13 (10.66) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Other | 22 (18.03) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.45 ± 13.13 | 38.04 ± 12.37 | .06 | 38.67 ± 12.43 | 40.78 ± 14.39 | .69 |

| Female | 50 (40.98) | 259 (42.25) | .84 | 6 (66.67) | 20 (51.28) | .47 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (37.71) | 197 (32.14) | .24 | 2 (22.22) | 11 (28.20) | 1.00 |

| Corticosteroids | 47 (37.70) | 298 (48.61) | .05 | 2 (22.22) | 20 (51.28) | .15 |

| Mayo score | 6.25 ± 2.42 | 5.08 ± 2.84 | <.01 | 3.67 ± 2.06 | 2.95 ± 1.67 | .35 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 6 (4.92) | 43 (7.01) | .06 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 113 (92.62) | 523 (85.32) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 3 (2.46) | 47 (7.67) | – | – | – | – |

| . | Golimumab . | Placebo . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | Racial Minority Participants . | White Participants . | P Value . | |

| Induction | ||||||

| n | 117 | 583 | 65 | 241 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 73 (62.39) | – | – | 48 (73.85) | – | – |

| Black | 16 (13.67) | – | – | 9 (13.84) | – | – |

| Other | 28 (23.93) | – | – | 8 (12.30) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.99 ± 13.64 | 39.02 ± 12.39 | .13 | 39.13 ± 12.63 | 38.91 ± 13.30 | .91 |

| Female | 48 (41.03) | 251 (43.05) | .76 | 26 (40.00) | 119 (49.38) | .21 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (39.32) | 177 (30.36) | .07 | 25 (38.46) | 67 (27.80) | .13 |

| Corticosteroids | 27 (23.08) | 186 (31.90) | .06 | 8 (12.31) | 76 (31.53) | <.01 |

| Mayo score | 8.53 ± 1.60 | 8.53 ± 1.51 | .99 | 8.28 ± 1.34 | 8.30 ± 1.42 | .89 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 7 (5.98) | 59 (10.12) | .40 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 56 (47.86) | 261 (44.77) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 54 (46.15) | 263 (45.11) | – | – | – | – |

| Maintenance (week 30) | ||||||

| n | 122 | 613 | 9 | 39 | ||

| Racial category | ||||||

| Asian | 87 (71.31) | – | – | 7 (77) | – | – |

| Black | 13 (10.66) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Other | 22 (18.03) | – | – | 1 (11) | – | – |

| Age, y | 40.45 ± 13.13 | 38.04 ± 12.37 | .06 | 38.67 ± 12.43 | 40.78 ± 14.39 | .69 |

| Female | 50 (40.98) | 259 (42.25) | .84 | 6 (66.67) | 20 (51.28) | .47 |

| Immunomodulators | 46 (37.71) | 197 (32.14) | .24 | 2 (22.22) | 11 (28.20) | 1.00 |

| Corticosteroids | 47 (37.70) | 298 (48.61) | .05 | 2 (22.22) | 20 (51.28) | .15 |

| Mayo score | 6.25 ± 2.42 | 5.08 ± 2.84 | <.01 | 3.67 ± 2.06 | 2.95 ± 1.67 | .35 |

| Induction dosage | ||||||

| 100/50 mg | 6 (4.92) | 43 (7.01) | .06 | – | – | – |

| 200/100 mg | 113 (92.62) | 523 (85.32) | – | – | – | – |

| 400/200 mg | 3 (2.46) | 47 (7.67) | – | – | – | – |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated.

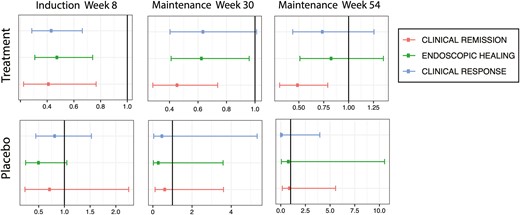

In the induction trial (NCT00487539), more White participants than participants from racial minority groups treated with golimumab achieved clinical response (57% vs 36%), clinical remission (23% vs 11%), and endoscopic healing (49% vs 32%) (P < .01 for all comparisons). After adjusting for confounders (age, sex, induction dose, baseline total Mayo score, and immunomodulator and corticosteroid use), participants from racial minority groups had a significantly lower odds of week 6 clinical response (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28-0.66), clinical remission (aOR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.22-0.77), and endoscopic healing (aOR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.31-0.74) compared with White participants (Figure 1). There were no statistically significant racial differences in placebo response rates during induction therapy.

Induction and maintenance outcomes for participants from racial minority groups compared with White participants in golimumab clinical trials. After induction (week 6), participants from racial minority groups were significantly less likely to achieve clinical response (top line), endoscopic healing (middle line), and clinical remission (bottom line) compared with White participants. Participants from racial minority groups continued to have significantly lower rates of clinical remission up to week 54 of maintenance. No significant differences in outcomes were observed between participants from racial minority groups and White participants who received placebo.

At week 30 of the maintenance trial (NCT00488631), more White participants than participants from racial minority groups treated with golimumab achieved clinical remission (43% vs 22%) and endoscopic healing (68% vs 53%) (P < .01 for both comparisons). After adjusting for confounders, participants from racial minority groups had significantly lower odds of clinical remission (aOR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.28-0.74) and endoscopic healing (aOR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-0.96) at week 30. Week 30 data also suggested decreased odds of clinical response among participants from racial minority groups, but this was not statistically significant (aOR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.40-1.01).

Owing to the design of the study that allowed for dose adjustment and placebo participants to receive golimumab if they experienced clinical loss of response, there were fewer participants remaining in the trial by week 54 who had only received placebo. Nonetheless, participants from racial minority groups also had a lower rate of clinical remission (54% vs 35%; P < .01) and were less likely to be in clinical remission (aOR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.31-0.79) at week 54 compared with White participants. Point estimates for clinical response (aOR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.44-1.25) and endoscopic healing (aOR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.51-1.35) at week 54 also suggested decreased efficacy of golimumab among participants from racial minority groups, but these results were not statistically significant. No significant differences in outcomes were observed between participants from racial minority groups and White participants who received placebo during maintenance.

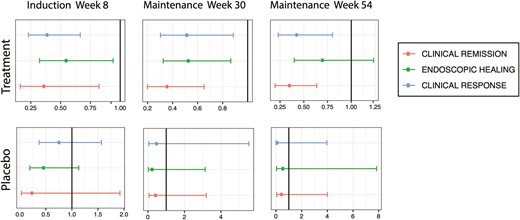

Results were similar in a subgroup analysis of only Asian participants (the largest proportion in the racial minority group) compared with White participants (Figure 2). After adjusting for confounders (age, sex, induction dose, baseline total Mayo score, and immunomodulator and corticosteroid use), Asian participants treated with golimumab were significantly less likely to achieve clinical response (aOR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.23-0.66), endoscopic healing (aOR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.32-0.94), and clinical remission (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.16-0.82) after induction. Asian participants continued to have significantly lower rates of clinical response (aOR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.23-0.80) and clinical remission (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.20-0.64) up to week 54 of maintenance. No significant differences in outcomes were observed between participants from the Asian subgroup and White participants who received placebo.

Induction and maintenance outcomes for the subgroup of Asian participants compared with White participants in golimumab clinical trials. After induction (week 6), participants from the Asian subgroup were significantly less likely to achieve clinical response (top line), endoscopic healing (middle line), and clinical remission (bottom line) compared with White participants. Asian participants continued to have significantly lower rates of clinical response and clinical remission up to week 54 of maintenance. No significant differences in outcomes were observed between participants from the Asian subgroup and White participants who received placebo.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of individual participant-level data from phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials of golimumab in adults with moderate-to-severe UC, participants from racial minority groups who received golimumab were less likely to achieve clinical response, clinical remission, and endoscopic healing compared with White participants. The decreased efficacy in clinical remission of golimumab among participants from racial minority groups was significant up to week 54. To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically examine the impact of race on response to biologics in IBD clinical trials.

It is notable that while we found racial differences in several primary and secondary outcomes in the golimumab-treated participants, we found no significant racial differences in any of the study outcomes in the placebo arm, thus suggesting a true difference in golimumab response between White participants and participants from racial minority groups. These findings are supported by previous observational research. A retrospective cohort study conducted at a tertiary IBD Center in the United Kingdom found that, even after adjusting for immunomodulator use and Montreal classification, Bangladeshi patients experienced significantly shorter failure-free survival and significantly higher TNF antagonist discontinuation due to loss of response over time compared with White patients.21 In contrast, the efficacy of adalimumab and golimumab in a Japanese population has been explored in a clinical trial setting and suggested that rates of outcomes are similar to those observed in original drug trials.22,23 It is unclear whether the lower clinical efficacy observed in our study is driven by any particular subgroup of participants. Population-level studies have suggested variation in the distribution of disease location and use of TNF antagonists by geographic region of origin among Asian subgroups with IBD. Compared with East Asian populations with UC, for instance, those in South Asian populations were found to have significantly more pancolitis and less proctitis.3 Additionally, early utilization of TNF antagonists was noted to be lower in Asian populations in the Asia Pacific compared with Western regions, suggesting geographic differences in UC management.24 However, protocolized treatment with golimumab was uniform in this clinical trial, which is expected to minimize treatment differences due to geographic region. While the number of participants from each geographic region was not available, the largest number of countries represented were from Eastern Europe, followed by Central and Western Europe. Other regions represented were in North America (United States, Canada), Oceania (Australia, New Zealand), Africa (South Africa), East Asia (Japan), Middle East (Israel), and South Asia (India). It is acknowledged that participants from any race may have participated from any region.

Underlying mechanisms of racial difference in the efficacy of golimumab observed in the current study are unclear. It is worth bearing in mind that race is a social category that is often associated with, but not explanatory of, biologic differences. The connection between race and health is often mediated by other nonbiological factors that encompass the social and physical environment.25-27 Access to health care, for example, is an essential component of receiving appropriate care, and African American and Hispanic IBD patients are more likely to be uninsured compared with White IBD patients.28 Adherence to medical treatment is also an important part of benefiting from health care, and factors such as patient trust in physician, insurance lapses, and cost of medications have been associated with lower patient adherence.29,30 Racial and ethnic minority groups disproportionately experience negative social determinants of health, and attention to these factors is key in understanding and addressing disparities in clinical outcomes.31

At the same time, there is also a growing body of research uncovering differences in the frequencies of genetic variants in diseases, which may contribute to differences in observed health outcomes among divergent ancestral populations.32,33 In IBD, genetic research has led to the discovery of specific risk loci as well as differential effect sizes and allele frequencies between IBD populations of divergent ancestries.5-8 These genetic differences suggest that there are potential variations in underlying pathways important in IBD inflammation that could plausibly impact response to therapy in different racial groups.

One of the challenges in further understanding how race may affect response to IBD biologic drugs is the relatively small number of participants from racial minority groups included in clinical trials. There is a longstanding disparity in clinical trial participation in the United States, whereby racial and ethnic minority groups have disproportionately low representation.34-37 Despite the increasing incidence and prevalence of IBD in racially diverse populations,14,38 individuals who identify as White make up the vast majority of participants in clinical trials.39 Infliximab is considered a first-line agent in IBD, but infliximab clinical trials included very few participants from racial and ethnic minority groups as outlined here. While golimumab is generally not considered a first-line agent, racial difference in response to golimumab antagonists has implications for treatment strategies in IBD. Our findings support increased attention to studying biologics in more racially diverse populations.

A strength of the current study is the clinical trial design from which the data were obtained, which provides a controlled setting in evaluating the contribution of race to biologic response. However, we acknowledge several limitations. First, the small number of placebo-treated participants remaining in the trial by week 54 may have affected the ability to detect statistical differences at this time point. However, given the consistent trends at week 54, the direction of study findings appears unaffected. Second, most participants from racial minority groups in this study were Asian (approximately 68%), so the findings of this study may not be generalizable to participants in Black and other racial categories, as they constituted a smaller percentage of racial minority group participants (approximately 13% and 19%, respectively). In addition, Hispanic ethnicity was not separately reported in any of the trials, therefore limiting conclusions about this population. Few IBD pharmaceutical trials report on Hispanic ethnicity,39 which, along with low numbers from racial minority groups, is a general limitation in the literature.

Conclusions

We observed that UC participants from racial minority groups experienced decreased clinical efficacy in treatment with golimumab during induction and maintenance clinical trials compared with White participants. As this is a post hoc analysis, these findings should be hypothesis-generating but do suggest that response rates to golimumab are lower in UC patients from racial minority groups. These results highlight the need for increased racial diversity in IBD clinical trial participation to understand if there is differential response to therapies by race. Further studies are needed to understand the decreased clinical efficacy observed in this study, whether these differences are observed with other biologic drugs, and potential explanatory factors.

Acknowledgments

This study, carried out under YODA Project #2018-3556, used data obtained from the Yale University Open Data Access Project, which has an agreement with Janssen Research and Development. The interpretation and reporting of research using this data are solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Yale University Open Data Access Project or Janssen Research and Development.

Funding

R.C.U. is funded by a National Institutes of Health K23 Career Development Award (K23KD111995-01A1). R.G. is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Science Einstein Montefiore CTSA Grant Number UL1TR001073.

Conflicts of Interest

R.G., F.P., and T.A.U. disclose no conflicts. J.F.C. has received research grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda; has received payment for lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Takeda, and Tillotts; has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Celgene Corporation, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Enterome, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Gilead, Iterative Scopes, Ipsen, Immunic, lmtbio, Inotrem, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Landos, LimmaTech Biologics AG, Medimmune, Merck, Novartis, O Mass, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Tigenix, and Viela bio; and holds stock options in Intestinal Biotech Development. R.C.U. has served as an advisory board member or consultant for AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; and received research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer.