-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Derick Todd, Antonio Hernandez-Madrid, Alessandro Proclemer, Maria Grazia Bongiorni, Heidi Estner, Carina Blomström-Lundqvist, Scientific Initiative Committee, European Heart Rhythm Association, Carina Blomström-Lundqvist, Maria Grazia Bongiorni, Jian Chen, Nikolaos Dagres, Heidi Estner, Antonio Hernandez-Madrid, Melece Hocini, Torben Bjerregaard Larsen, Laurent Pison, Tatjana Potpara, Alessandro Proclemer, Elena Sciraffia, Derick Todd, Irene Savelieva, Scientific Initiative Committee, European Heart Rhythm Association, How are arrhythmias detected by implanted cardiac devices managed in Europe? Results of the European Heart Rhythm Association Survey, EP Europace, Volume 17, Issue 9, September 2015, Pages 1449–1453, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euv310

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The management of arrhythmias detected by implantable cardiac devices can be challenging. There are no formal international guidelines to inform decision-making. The purpose of this European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) survey was to assess the management of various clinical scenarios among members of the EHRA electrophysiology research network. There were 49 responses to the questionnaire. The survey responses were mainly (81%) from medium–high volume device implanting centres, performing more than 200 total device implants per year. Clinical scenarios were described focusing on four key areas: the implantation of pacemakers for bradyarrhythmia detected on an implantable loop recorder (ILR), the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmia detected by an ILR or pacemaker, the management of atrial fibrillation in patients with pacemakers and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices and the management of ventricular tachycardia in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators.

Introduction

Over 250 000 devices are implanted annually in Europe,1 and all of these devices have the ability to store details of arrhythmias, either as patient-activated events or as automatic recordings within pre-programmed criteria (normally heart rate). In many patients, additional arrhythmias to the original device indication will be detected and require management. There are no international guidelines on how to manage such arrhythmias. The purpose of this European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) survey was to assess how physicians within the EHRA electrophysiology (EP) research network managed a series of clinical scenarios often seen within device follow-up.

Methods

Participating centres

This survey is based on a questionnaire sent via the internet to the EHRA EP research network centres. Overall, 46 institutions responded, with 2 replies from 3 centres (all in the UK). There was a wide geographical distribution from 17 countries (19 centres in the UK, 5 in Spain, 3 in Italy and Denmark, 2 in Armenia, Austria, and Georgia, and 1 centre in each from Belgium, Brazil, Estonia, Greece, Luxemburg, The Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Romania, and Serbia). The majority of centres (78%) were university hospitals, with 3 private hospitals (6%) and 8 (16%) other types of hospital. Hospital procedure numbers are shown in Table 1. Most centres (81%) were high volume implanting (>200 per annum) centres.

| Implant numbers | 0 | 1–49 | 50–99 | 100–199 | >200 |

| All devices | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 40 |

| Pacemakers | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 31 |

| Loop recorders | 7 | 21 | 11 | 7 | 0 |

| ICD | 1 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 15 |

| CRT | 2 | 14 | 15 | 9 | 6 |

| Implant numbers | 0 | 1–49 | 50–99 | 100–199 | >200 |

| All devices | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 40 |

| Pacemakers | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 31 |

| Loop recorders | 7 | 21 | 11 | 7 | 0 |

| ICD | 1 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 15 |

| CRT | 2 | 14 | 15 | 9 | 6 |

CRT, cardiac resynchronisation therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

| Implant numbers | 0 | 1–49 | 50–99 | 100–199 | >200 |

| All devices | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 40 |

| Pacemakers | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 31 |

| Loop recorders | 7 | 21 | 11 | 7 | 0 |

| ICD | 1 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 15 |

| CRT | 2 | 14 | 15 | 9 | 6 |

| Implant numbers | 0 | 1–49 | 50–99 | 100–199 | >200 |

| All devices | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 40 |

| Pacemakers | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 31 |

| Loop recorders | 7 | 21 | 11 | 7 | 0 |

| ICD | 1 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 15 |

| CRT | 2 | 14 | 15 | 9 | 6 |

CRT, cardiac resynchronisation therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Bradyarrhythmia detected by implantable loop recorders

The first scenario was that of a patient with a history of syncope, a normal 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and a structurally normal heart on echocardiography. The issue we explored was the threshold for pacemaker implantation based on the duration of monitored asystole and the presence or absence of symptoms. It was clear that symptoms were important in the decision to implant a pacemaker. In the absence of symptoms, only 7% of respondents would implant a pacemaker for a 3 s pause, whereas 72% would implant a pacemaker for a symptomatic 3 s pause, and a further 18% for a 5 s pause. In the absence of symptoms a pause of duration of 5 s was considered an indication for pacemaker by 40% of centres, whereas 23% would require a pause to be >10 s and 30% indicated that they would not implant a pacemaker for any asymptomatic pause.

Broad complex tachycardia detected by implantable loop recorders

For implantable loop recorder (ILR) detected broad QRS complex tachycardia (BCT), we explored two scenarios for a patient with a history of syncope. In the first scenario, the patient had a normal 12-lead ECG and a structurally normal heart on echocardiography. For ‘normal heart’ ventricular tachycardia (VT), there was virtual universal agreement (93% of respondents) that an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was not indicated for an asymptomatic run of non-sustained VT at 200 bpm. However, if the patient had been symptomatic, 35% of centres indicated that they would consider an ICD implant, although 65% of centres still did not consider an ICD in such a case. Of the 35% who would consider an ICD for a patient with a normal heart and history of syncope, 12% would consider it for a 3 s run of BCT, 9% for a 5 s run, and 14% for a run >10 s.

In the second scenario, the patient with a history of syncope had structural heart disease, defined as a previous anterior myocardial infarction and an ejection fraction (EF) of 40% on echocardiography (chosen so as not to overlap with current primary prevention ICD indications). Slightly more than half of the centres (53%) did not feel an ICD was indicated for asymptomatic BCT, although a significant proportion (28%) felt that a 3 s run of BCT was enough to proceed to ICD implantation. For symptomatic BCT, 65% of respondents would implant an ICD, although there was also a wide variation in practice with 40% feeling an ICD was indicated for a 3 s episode, 12% for a 5 s episode, and 14% for a 10 s episode. However, 35% of centres still did not feel an ICD was indicated even for an episode of BCT >10 s with symptoms, even with an EF of 40%.

For pacemaker-detected tachycardia, we explored six scenarios, all in patients with underlying complete heart block, to strongly imply that any ventricular high-rate episodes were VT. In the first two scenarios, the patient was asymptomatic and had either an EF of 50 or 40% on echocardiography. We specified a rate of 185 bpm lasting 10 s. When EF was 50% and the patient was asymptomatic, no respondents chose to upgrade to an ICD, although most (74%) would start a β-blocker and investigate the patient's coronary artery status (58%). A significant proportion of centres (19%) take no action in this situation. In the scenario where the patient had symptoms and an EF of 40%, upgrade to ICD was considered by 28% of centres, with similar proportions starting β-blocker (77%), and investigating coronary status (65%). Only 5% of centres took no action.

In the next four scenarios, we defined the high-rate episode as 200 bpm lasting 15 s. We explored how left ventricular function and symptoms affected management. In the first comparison, the patient had normal left ventricular function and we assessed how management was affected by symptoms. In the absence of symptoms, physicians were considerably more conservative, mostly advising β-blocker (71%) and coronary investigation (61%) but rarely an ICD (7%). If symptomatic, a β-blocker was recommended by 93% and coronary investigation by 71%. The presence of symptoms also served as a trigger for recommending an ICD for 20% (symptoms were not defined). Ablation was recommended by 15% of respondents.

When the same questions were asked but the scenario changed to a patient with an EF of 40%, the use of ICD increased significantly to 34% for asymptomatic episodes, and 46% in the presence of symptoms. For both groups the vast majority advised a β-blocker and coronary investigation. Ablation was still a favoured option in the presence of symptoms for 12% of centres.

Atrial fibrillation detected by implanted devices

We explored the two key elements of atrial fibrillation (AF) management. First we explored the threshold for anticoagulation dependent on the duration of device-detected atrial arrhythmia and the patient's CHA2DS2-VASc score. Second, we asked about rate vs. rhythm control management strategies in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators (CRT-Ds).

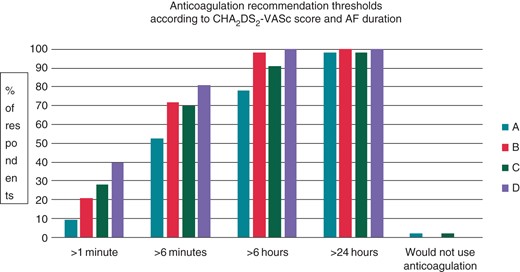

The scenarios we explored involved patients with dual-chamber pacemakers, implanted for sinus node disease, coming for a routine 6-month follow-up appointment. We wanted to understand how respondents' threshold for recommending anticoagulation would vary according to the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and the number and duration of device-detected AF events. The results are shown in Figure 1 and indicate that the threshold for initiation of anticoagulation is highly variable, but in general that the higher the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and the longer and more frequent AF episodes are, the more likely cardiologists are to recommend anticoagulation.

Physician recommendation of anticoagulation for four scenarios. (A) CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2–3, single atrial high-rate event. (B) CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2–3, multiple (>2) AHREs. (C) CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4, single atrial high-rate event. (D) CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4, multiple (>2) atrial high-rate events.

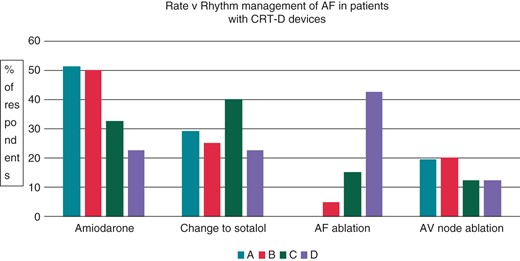

We also wanted to assess strategies for rate control vs. rhythm management in patients with CRT devices with both symptomatic and symptomatic device-detected AF. The results are shown in Figure 2. There was a clear trend to lower use of amiodarone in younger patients, and to a higher use of ablation to control AF in patients who are younger and symptomatic.

Atrial fibrillation management in CRT-D patients (single episode of 72 h). (A) The 78-year-old patient with an asymptomatic 72 h episode. (B) The 78-year-old patient with a symptomatic 72 h episode. (C) The 53-year-old patient with an asymptomatic 72 h episode. (D) The 53-year-old patient with a symptomatic 72 h episode.

Management of a first ICD shock for monomorphic ventricular tachycardia

In the final clinical scenario, we asked how respondents would manage a patient with a history of ischaemic heart disease, and a primary prevention ICD, who presented following a first ICD shock for monomorphic VT at a rate of 200 bpm, unresponsive to antitachycardia pacing (ATP). We presented the same scenario for a 60-year-old and a 75-year-old patient. The results are shown in Table 2. There is a clear trend towards lower use of amiodarone and more use of ablation in the younger patient.

Management of ischaemic, monomorphic VT, unresponsive to ATP, in a patient with a first ICD shock

| Management option . | 60-year-old (%) . | 75-year-old (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Start amiodarone | 17.5 | 47.5 |

| Change β-blocker to sotalol | 5 | 2.5 |

| Change ATP regime | 32.5 | 22.5 |

| Refer for VT ablation | 45 | 27.5 |

| Management option . | 60-year-old (%) . | 75-year-old (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Start amiodarone | 17.5 | 47.5 |

| Change β-blocker to sotalol | 5 | 2.5 |

| Change ATP regime | 32.5 | 22.5 |

| Refer for VT ablation | 45 | 27.5 |

ATP, antitachycardia pacing; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Management of ischaemic, monomorphic VT, unresponsive to ATP, in a patient with a first ICD shock

| Management option . | 60-year-old (%) . | 75-year-old (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Start amiodarone | 17.5 | 47.5 |

| Change β-blocker to sotalol | 5 | 2.5 |

| Change ATP regime | 32.5 | 22.5 |

| Refer for VT ablation | 45 | 27.5 |

| Management option . | 60-year-old (%) . | 75-year-old (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Start amiodarone | 17.5 | 47.5 |

| Change β-blocker to sotalol | 5 | 2.5 |

| Change ATP regime | 32.5 | 22.5 |

| Refer for VT ablation | 45 | 27.5 |

ATP, antitachycardia pacing; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Discussion

The results of this survey indicate that there is a significant variation in the management of device-detected arrhythmias. It was not possible to assess how this varied geographically due to the large number of countries with only a single responding centre.

Recommendations for pacemaker implantation are highly dependent on the underlying rhythm disturbance.2 It was not possible from our questions to understand what form of bradycardia respondents were considering in their answers. Asymptomatic pauses of 3 s detected by an ILR would certainly be a pacemaker indication in a patient with a prior history of syncope if there was documentation of atrioventricular block, or the patient had underlying sinus node disease. However, if the ILR was implanted for a suspicion of vasovagal syncope, the results of the ISSUE-3 (International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology) study3 would suggest that pacing should be reserved for asymptomatic pauses >6 s, and symptomatic pauses >3 s. It is interesting that 30% of centres would not routinely implant a pacemaker for an asymptomatic >10 s pause detected by an ILR. This ‘high threshold’ for pacing was common in the UK centres where 44% of respondents did not offer pacing for any asymptomatic pauses. A previous EP wire in 2013 noted that pacing is used rarely in European centres for vasovagal syncope.4

The management of ventricular arrhythmias is always challenging for the cardiologist. There has been an updated guidance published recently.5 Implantation of an ICD in ‘normal heart’ VT is in general not recommended, unless VT is polymorphic or associated with an ion-channel disorder. However, the initial symptom status at presentation is not commented on in the consensus document, and it is clear from our survey that when the patient has a history of syncope that approximately one-third of cardiologists will implant an ICD for symptomatic VT in a patient with a structurally normal heart, and two-thirds will implant an ICD if EF is 40%. Within the survey we did not offer the choice to perform electrophysiological testing and we recognize that with an EF of 40% some respondents may have preferred this strategy. The influence of symptoms at presentation on management should perhaps be considered in a subsequent guidance.

The management of non-sustained VT in pacemaker patients is in line with the 2014 EHRA/HRS/APHRS consensus document5 with the majority of cardiologists focusing on assessment of coronary status and the use of β-blockers. It is clear that as EF reduces from 50% where no respondents generally offer an ICD for pacemaker-detected VT at 185 bpm, to an EF of 40% where 29% offer an ICD that left ventricular function is an important determinant in decision-making. The rate of VT is also important though, as when the rate was 200 bpm an upgrade to ICD was considered by 7% even for patients with normal left ventricular function, and in 46% when the EF was 40% and the patient symptomatic.

Cardiologists have understood for a number of years that device-detected atrial high-rate events (AHREs) are associated with a risk of stroke.6 Subsequent studies have confirmed this link, but the risk/benefit ratio of anticoagulation in such patients is not clear.7,8 In addition, there are also data indicating that a combination of device-detected AF duration combined with the CHADS2 score can identify high-risk patients.9

There was a significant variation in the use of anticoagulation for device-detected AHREs, which, for the purposes of discussion, we will consider as AF. This reflects the emergence of new data confirming an association between AHRE episodes and increased risk of stroke. The increased risk of stroke, at an approximate relative risk of 2,3,4,10 is not as high as the five times higher risk noted for persistent AF.11 The variation in practice is therefore quite understandable as at this time there are also no published randomized trials confirming a benefit for anticoagulation for device-only detected AF, although trials are underway (e.g. ARTESiA, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01938248).

Perhaps, surprisingly our results show that a rhythm control policy either with drugs or with ablation was favoured in the majority of patients with 80% of respondents recommending this (either in the form of amiodarone, switching to sotalol, or using AF ablation) for the 78-year-old patient and 87.5% for the 53-year-old patient with a CRT-D. It was interesting to understand that despite the data from AFFIRM (Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management)12 of equivalence in outcomes between rate and rhythm control strategies in AF, 80% of respondents still prefer rhythm control in patients with a CRT-D device, even in the absence of symptoms. It is likely that this reflects a belief that such patients are more prone to deterioration in heart failure with the onset of AF. We may have expected that atrioventricular node ablation would be used more widely, than the observed 20%, in these patients.

Finally, the management of monomorphic VT resulting in an ICD shock is influenced by the patients age with amiodarone preferred in older patients.

Limitations

By their very nature short clinical scenarios cannot cover every aspect of the patient's history and clinical findings. In addition, not all possible management plans can be provided as an option. The main limitations in the scenarios were that we did not describe symptoms and therefore these were open to interpretation. In addition, we did not offer the option of an electrophysiological study to assess inducibility of VT as an option for patients with an EF of 40%.

Acknowledgements

The production of this EP wire document is under the responsibility of the Scientific Initiative Committee of the European Heart Rhythm Association 2013–15: Carina Blomström-Lundqvist (Chair), Maria Grazia Bongiorni (Co-chair), Jian Chen, Nikolaos Dagres, Heidi Estner, Antonio Hernandez-Madrid, Melece Hocini, Torben Bjerregaard Larsen, Laurent Pison, Tatjana Potpara, Alessandro Proclemer, Elena Sciraffia, Derick Todd. Document reviewer for EP-Europace: Irene Savelieva (St George's University of London, London, UK). The authors acknowledge the EHRA Research Network centres participating in this EP-Wire. A list of the Research Network can be found on the EHRA website.

Conflict of interest: none declared.