-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rose Anne Kenny, Michele Brignole, Gheorghe-Andrei Dan, Jean Claude Deharo, J. Gert van Dijk, Colin Doherty, Mohamed Hamdan, Angel Moya, Steve W. Parry, Richard Sutton, Andrea Ungar, Wouter Wieling, External contributors to the Task Force:, Mehran Asgari, Gonzalo Baron-Esquivias, Jean-Jacques Blanc, Ivo Casagranda, Conal Cunnigham, Artur Fedorowski, Raffello Furlan, Nicholas Gall, Frederik J. De Lange, Geraldine Mcmahon, Peter Mitro, Artur Pietrucha, Cristian Podoleanu, Antonio Raviele, David Benditt, Andrew Krahn, Carlos Arturo Morillo, Brian Olshansky, Satish Raj, Robert Sheldon, Win Kuang Shen, Benjamin Sun, Denise Hachul, Haruhiko Abe, Toshyuki Furukawa, Document reviewers: Review coordinators, Bulent Gorenek, Gregory Y. H. Lip, Michael Glikson, Philippe Ritter, Jodie Hurwitz, Robert Macfadyen, Andrew Rankin, Luis Mont, Jesper Svendsen, Fred Kusumoto, Mitchell Cohen, Irene Savelieva, Syncope Unit: rationale and requirement – the European Heart Rhythm Association position statement endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society, EP Europace, Volume 17, Issue 9, September 2015, Pages 1325–1340, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euv115

Close - Share Icon Share

Scope of the document

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has played an important role in advancing our understanding of the causes, optimal investigation, and management of syncope through publication of practice guidelines in 2001, 2004, and 2009.1–3 The 2009 ESC guidelines recommend the establishment of formal Syncope Units (SUs)—either virtual or physical site within a hospital or clinic facility—with access to syncope specialists and specialized equipment.3 In response, this position statement by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) offers a pragmatic approach to the rationale and requirement for an SU, based on specialist consensus, existing practice and scientific evidence (see Appendix).

The panel consists of specialists who have experience in developing and leading such units representing cardiology, geriatric and general internal medicine, neurology, and emergency medicine.

This document is addressed to physicians and others in administration, who are interested in establishing an SU in their hospital, so that they can meet the standards proposed by ESC-EHRA-HRS.1–3

Definitions

Definition of syncope and transient loss of consciousness

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness (T-LOC) due to transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, and is characterized by rapid onset, short duration, and spontaneous complete recovery. This definition of syncope has been developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the ESC and endorsed by the EHRA, European Heart Failure Association and European Heart Rhythm Society. Transient loss of consciousness is a term that encompasses all disorders characterized by self-limited LOC, irrespective of mechanism.1–3 By including the mechanism of unconsciousness, i.e. transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, the current syncope definition excludes other causes of T-LOC such as epileptic seizures and concussion, as well as certain common syncope mimics, such as psychogenic pseudosyncope.

Definition of a Syncope Unit

An SU is a facility featuring a standardized approach to the diagnosis and management of T-LOC and related symptoms, with dedicated staff and access to appropriate diagnostics and therapies. The SU should also take the lead in educating and training clinicians who encounter syncope. Even if the most appropriate term describing such an organization should be the more general T-LOC Unit (or Faint Unit), this Task Force decided to maintain the term of SU, because it is most frequently used worldwide. This Position Paper is a pragmatic approach to outline the constituents of an SU and assist target groups with the current available necessary information. The authors emphasize that there is, at present, insufficient available evidence whether an SU (examples of a number of models are detailed later in the document) is superior in efficiency or outcomes to a syncope specialist4 or newer technologically driven models of syncope management.5 We anticipate that the Position Paper will stimulate structured research to determine best practice models for T-LOC evaluation in different settings and cultures.

Rationale for a Syncope Unit

Expected benefit and barriers to setting-up a Syncope Unit

Syncope is a common medical problem that can be debilitating and associated with high healthcare costs.6–9 There is wide variation in practice of syncope evaluation, and wide variation in adoption of recommendations from published guidelines.10,11 The absence of a systematic approach to T-LOC incurs higher health and social care costs, unnecessary hospitalizations, and diagnostic procedures, prolongation of hospital stays, lower diagnostic rates, and higher rates of symptom recurrences. Therefore, a systematic approach, by a dedicated service (an SU), equipped to evaluate and manage this common problem may ensure better management of T-LOC, from risk stratification to diagnosis, therapy and follow-up (Table 1).

| Expected benefits . |

|---|

| Specialist opinion for patients |

| Early accurate and efficient diagnosis |

| Timely treatment |

| Better application of recommended guidelines |

| Less duplication and fragmentation of services |

| Single source of communication for all stakeholders |

| Shorter length of stay for hospital inpatients |

| Reduction of total care costs |

| Better systems for monitoring and evaluation of practice at local, national, and international level |

| Better quality control at local, national and international level |

| Access to harmonized data across different hospitals |

| High quality, evidence-based data for research |

| Evidence-based innovation in diagnosis, treatments and healthcare model |

| Expected benefits . |

|---|

| Specialist opinion for patients |

| Early accurate and efficient diagnosis |

| Timely treatment |

| Better application of recommended guidelines |

| Less duplication and fragmentation of services |

| Single source of communication for all stakeholders |

| Shorter length of stay for hospital inpatients |

| Reduction of total care costs |

| Better systems for monitoring and evaluation of practice at local, national, and international level |

| Better quality control at local, national and international level |

| Access to harmonized data across different hospitals |

| High quality, evidence-based data for research |

| Evidence-based innovation in diagnosis, treatments and healthcare model |

| Expected benefits . |

|---|

| Specialist opinion for patients |

| Early accurate and efficient diagnosis |

| Timely treatment |

| Better application of recommended guidelines |

| Less duplication and fragmentation of services |

| Single source of communication for all stakeholders |

| Shorter length of stay for hospital inpatients |

| Reduction of total care costs |

| Better systems for monitoring and evaluation of practice at local, national, and international level |

| Better quality control at local, national and international level |

| Access to harmonized data across different hospitals |

| High quality, evidence-based data for research |

| Evidence-based innovation in diagnosis, treatments and healthcare model |

| Expected benefits . |

|---|

| Specialist opinion for patients |

| Early accurate and efficient diagnosis |

| Timely treatment |

| Better application of recommended guidelines |

| Less duplication and fragmentation of services |

| Single source of communication for all stakeholders |

| Shorter length of stay for hospital inpatients |

| Reduction of total care costs |

| Better systems for monitoring and evaluation of practice at local, national, and international level |

| Better quality control at local, national and international level |

| Access to harmonized data across different hospitals |

| High quality, evidence-based data for research |

| Evidence-based innovation in diagnosis, treatments and healthcare model |

| Barriers to establishing an SU . |

|---|

| Lack of awareness of the benefits of an SU due to inadequate research trials comparing SUs to normal practice |

| Underestimation of consequences of syncope |

| Lack of awareness of benefit of an SU on quality-of-life |

| Low numbers of syncope specialists |

| Lack of formal syncope training programmes |

| Wide age range from paediatric to oldest patients |

| Skill sets required in a number of domains such as cardiology, geriatrics, paediatrics, physiology, neurology, and psychiatry |

| Syncope not a recognized subspecialty |

| Reluctance to introduce innovative proposals |

| Necessity to engage multiple stakeholders |

| Inadequate reimbursement of syncope core management |

| New economic cost models required to evaluate an SU |

| Fear of increasing costs by the development of a new structure instead of reducing them |

| Barriers to establishing an SU . |

|---|

| Lack of awareness of the benefits of an SU due to inadequate research trials comparing SUs to normal practice |

| Underestimation of consequences of syncope |

| Lack of awareness of benefit of an SU on quality-of-life |

| Low numbers of syncope specialists |

| Lack of formal syncope training programmes |

| Wide age range from paediatric to oldest patients |

| Skill sets required in a number of domains such as cardiology, geriatrics, paediatrics, physiology, neurology, and psychiatry |

| Syncope not a recognized subspecialty |

| Reluctance to introduce innovative proposals |

| Necessity to engage multiple stakeholders |

| Inadequate reimbursement of syncope core management |

| New economic cost models required to evaluate an SU |

| Fear of increasing costs by the development of a new structure instead of reducing them |

| Barriers to establishing an SU . |

|---|

| Lack of awareness of the benefits of an SU due to inadequate research trials comparing SUs to normal practice |

| Underestimation of consequences of syncope |

| Lack of awareness of benefit of an SU on quality-of-life |

| Low numbers of syncope specialists |

| Lack of formal syncope training programmes |

| Wide age range from paediatric to oldest patients |

| Skill sets required in a number of domains such as cardiology, geriatrics, paediatrics, physiology, neurology, and psychiatry |

| Syncope not a recognized subspecialty |

| Reluctance to introduce innovative proposals |

| Necessity to engage multiple stakeholders |

| Inadequate reimbursement of syncope core management |

| New economic cost models required to evaluate an SU |

| Fear of increasing costs by the development of a new structure instead of reducing them |

| Barriers to establishing an SU . |

|---|

| Lack of awareness of the benefits of an SU due to inadequate research trials comparing SUs to normal practice |

| Underestimation of consequences of syncope |

| Lack of awareness of benefit of an SU on quality-of-life |

| Low numbers of syncope specialists |

| Lack of formal syncope training programmes |

| Wide age range from paediatric to oldest patients |

| Skill sets required in a number of domains such as cardiology, geriatrics, paediatrics, physiology, neurology, and psychiatry |

| Syncope not a recognized subspecialty |

| Reluctance to introduce innovative proposals |

| Necessity to engage multiple stakeholders |

| Inadequate reimbursement of syncope core management |

| New economic cost models required to evaluate an SU |

| Fear of increasing costs by the development of a new structure instead of reducing them |

Comparison between systematic evaluation and conventional management of syncope in controlled studies

| Source . | Intervention . | Comparison setting . | Number of patients . | Main results (experimental vs. conventional group) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenny et al.12 UK | Day-case falls and syncope unit in adults | Bed day activity in hospitals with (E) vs. hospitals without day-care facility (C) | – | 64% reduction in admissions in hospital with falls and syncope |

| Brignole et al.13 Italy | In-hospital Syncope Unit within the Department of Cardiology | 6 hospitals with Syncope Unit (E) vs. 6 hospitals without (C) Syncope Unit | 274 (C) vs. 279 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope 8% reduction of tests 12% reduction in admissions |

| Farwell and Sulke14 UK | Diagnostic/management protocol for syncope | One year with protocol (E) vs. previous year in one hospital | 660 (C) vs. 421 (E) | 166% increase in costs per patient: despite improved diagnosis, inappropriate investigation and admission still occurred |

| Shen et al.15 USA | Syncope Unit in the ED | Rate of admission and diagnosis in patients randomized to Syncope Units (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 51 (C) vs. 52 (E) | 63% reduction in unexplained syncope 56% reduction in admissions |

| Blanc et al.16 France | Education of ED physicians on T-LOC/syncope | One year before (C) vs. 1 year after education (E) | 454 (C) vs. 524 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope −25% reduction in admissions |

| Brignole et al.17 Italy | Standardized care using ESC guidelines | 28 hospitals with standard care (C) vs. 19 with standardized care (E) | 929 (C) vs. 745 (E) | 25% reduction in unexplained syncope 24% reduction of tests 17% reduction in admissions 19% reduction of costs per patient |

| Parry et al.18 UK | Education through management algorithm for acute medical services; effect on patient admitted for falls and syncope | One-month period before (C) vs. 1-month period a year later (E) | 41 (C) vs. 31 (E) | 2% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| Ammirati et al.19 Italy | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope referred to Syncope Unit; period before patients visited Syncope Unit (C) vs. after visit (E) | 96 | 82% reduction in unexplained syncope −85% reduction of costs per patient |

| Fedorowski et al.20 Sweden | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope patients discharged from ED or hospital ward (C) vs. the same patients evaluated by SU (E) | 101 | 87% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| McCarthy et al.21 Ireland | Using ESC Guidelines | Utilization of resources in ED (C) vs. re-evaluation of same patients using ESC guidelines; 6-month period | 214 | 54% reduction in admissions |

| Daccarett et al.22 USA | ESC Guidelines incorporated in ‘Faint-Algorithm’ | Retrospective assessment of ED admissions | 254 | 52% reduction in admissions |

| Shin et al.23 South Korea | Standardized ED protocol for syncope based on ESC guidelines | Period before (C) and after (E) standardization | 116 (C) vs. 128 (E) | 28% reduction in unexplained syncope 39% reduction in admissions 32% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sun24 USA | Up to 24 h observation ED | ED syncope presentation with usual care (C) or observation period (E) for intermediate-risk patients | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 42% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sanders et al.25 USA | Standardized care implemented in Faint and Fall Clinic vs. historical control | Standardized care (E) vs. historical control (C) | 100 (C) vs. 154 (E) | 22% reduction in unexplained syncope 80% reduction in admissions |

| Sun et al.26 USA | Observation Unit in five EDs | Rate of admission and costs in patients >50 years, randomized to observation unit (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 629 $ reduction in index hospital costs |

| Raucci et al.27 Italy | Standardized care implemented of paediatric guidelines vs. historical control in ED | Two years with protocol (E) vs. previous 2 years in one hospital | 470 (C) vs. 603 (E) | 72% reduction in unexplained syncope 54% reduction in admissions |

| Source . | Intervention . | Comparison setting . | Number of patients . | Main results (experimental vs. conventional group) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenny et al.12 UK | Day-case falls and syncope unit in adults | Bed day activity in hospitals with (E) vs. hospitals without day-care facility (C) | – | 64% reduction in admissions in hospital with falls and syncope |

| Brignole et al.13 Italy | In-hospital Syncope Unit within the Department of Cardiology | 6 hospitals with Syncope Unit (E) vs. 6 hospitals without (C) Syncope Unit | 274 (C) vs. 279 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope 8% reduction of tests 12% reduction in admissions |

| Farwell and Sulke14 UK | Diagnostic/management protocol for syncope | One year with protocol (E) vs. previous year in one hospital | 660 (C) vs. 421 (E) | 166% increase in costs per patient: despite improved diagnosis, inappropriate investigation and admission still occurred |

| Shen et al.15 USA | Syncope Unit in the ED | Rate of admission and diagnosis in patients randomized to Syncope Units (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 51 (C) vs. 52 (E) | 63% reduction in unexplained syncope 56% reduction in admissions |

| Blanc et al.16 France | Education of ED physicians on T-LOC/syncope | One year before (C) vs. 1 year after education (E) | 454 (C) vs. 524 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope −25% reduction in admissions |

| Brignole et al.17 Italy | Standardized care using ESC guidelines | 28 hospitals with standard care (C) vs. 19 with standardized care (E) | 929 (C) vs. 745 (E) | 25% reduction in unexplained syncope 24% reduction of tests 17% reduction in admissions 19% reduction of costs per patient |

| Parry et al.18 UK | Education through management algorithm for acute medical services; effect on patient admitted for falls and syncope | One-month period before (C) vs. 1-month period a year later (E) | 41 (C) vs. 31 (E) | 2% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| Ammirati et al.19 Italy | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope referred to Syncope Unit; period before patients visited Syncope Unit (C) vs. after visit (E) | 96 | 82% reduction in unexplained syncope −85% reduction of costs per patient |

| Fedorowski et al.20 Sweden | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope patients discharged from ED or hospital ward (C) vs. the same patients evaluated by SU (E) | 101 | 87% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| McCarthy et al.21 Ireland | Using ESC Guidelines | Utilization of resources in ED (C) vs. re-evaluation of same patients using ESC guidelines; 6-month period | 214 | 54% reduction in admissions |

| Daccarett et al.22 USA | ESC Guidelines incorporated in ‘Faint-Algorithm’ | Retrospective assessment of ED admissions | 254 | 52% reduction in admissions |

| Shin et al.23 South Korea | Standardized ED protocol for syncope based on ESC guidelines | Period before (C) and after (E) standardization | 116 (C) vs. 128 (E) | 28% reduction in unexplained syncope 39% reduction in admissions 32% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sun24 USA | Up to 24 h observation ED | ED syncope presentation with usual care (C) or observation period (E) for intermediate-risk patients | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 42% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sanders et al.25 USA | Standardized care implemented in Faint and Fall Clinic vs. historical control | Standardized care (E) vs. historical control (C) | 100 (C) vs. 154 (E) | 22% reduction in unexplained syncope 80% reduction in admissions |

| Sun et al.26 USA | Observation Unit in five EDs | Rate of admission and costs in patients >50 years, randomized to observation unit (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 629 $ reduction in index hospital costs |

| Raucci et al.27 Italy | Standardized care implemented of paediatric guidelines vs. historical control in ED | Two years with protocol (E) vs. previous 2 years in one hospital | 470 (C) vs. 603 (E) | 72% reduction in unexplained syncope 54% reduction in admissions |

E, experimental group; C, control group; ED, Emergency Department.

Comparison between systematic evaluation and conventional management of syncope in controlled studies

| Source . | Intervention . | Comparison setting . | Number of patients . | Main results (experimental vs. conventional group) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenny et al.12 UK | Day-case falls and syncope unit in adults | Bed day activity in hospitals with (E) vs. hospitals without day-care facility (C) | – | 64% reduction in admissions in hospital with falls and syncope |

| Brignole et al.13 Italy | In-hospital Syncope Unit within the Department of Cardiology | 6 hospitals with Syncope Unit (E) vs. 6 hospitals without (C) Syncope Unit | 274 (C) vs. 279 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope 8% reduction of tests 12% reduction in admissions |

| Farwell and Sulke14 UK | Diagnostic/management protocol for syncope | One year with protocol (E) vs. previous year in one hospital | 660 (C) vs. 421 (E) | 166% increase in costs per patient: despite improved diagnosis, inappropriate investigation and admission still occurred |

| Shen et al.15 USA | Syncope Unit in the ED | Rate of admission and diagnosis in patients randomized to Syncope Units (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 51 (C) vs. 52 (E) | 63% reduction in unexplained syncope 56% reduction in admissions |

| Blanc et al.16 France | Education of ED physicians on T-LOC/syncope | One year before (C) vs. 1 year after education (E) | 454 (C) vs. 524 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope −25% reduction in admissions |

| Brignole et al.17 Italy | Standardized care using ESC guidelines | 28 hospitals with standard care (C) vs. 19 with standardized care (E) | 929 (C) vs. 745 (E) | 25% reduction in unexplained syncope 24% reduction of tests 17% reduction in admissions 19% reduction of costs per patient |

| Parry et al.18 UK | Education through management algorithm for acute medical services; effect on patient admitted for falls and syncope | One-month period before (C) vs. 1-month period a year later (E) | 41 (C) vs. 31 (E) | 2% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| Ammirati et al.19 Italy | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope referred to Syncope Unit; period before patients visited Syncope Unit (C) vs. after visit (E) | 96 | 82% reduction in unexplained syncope −85% reduction of costs per patient |

| Fedorowski et al.20 Sweden | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope patients discharged from ED or hospital ward (C) vs. the same patients evaluated by SU (E) | 101 | 87% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| McCarthy et al.21 Ireland | Using ESC Guidelines | Utilization of resources in ED (C) vs. re-evaluation of same patients using ESC guidelines; 6-month period | 214 | 54% reduction in admissions |

| Daccarett et al.22 USA | ESC Guidelines incorporated in ‘Faint-Algorithm’ | Retrospective assessment of ED admissions | 254 | 52% reduction in admissions |

| Shin et al.23 South Korea | Standardized ED protocol for syncope based on ESC guidelines | Period before (C) and after (E) standardization | 116 (C) vs. 128 (E) | 28% reduction in unexplained syncope 39% reduction in admissions 32% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sun24 USA | Up to 24 h observation ED | ED syncope presentation with usual care (C) or observation period (E) for intermediate-risk patients | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 42% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sanders et al.25 USA | Standardized care implemented in Faint and Fall Clinic vs. historical control | Standardized care (E) vs. historical control (C) | 100 (C) vs. 154 (E) | 22% reduction in unexplained syncope 80% reduction in admissions |

| Sun et al.26 USA | Observation Unit in five EDs | Rate of admission and costs in patients >50 years, randomized to observation unit (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 629 $ reduction in index hospital costs |

| Raucci et al.27 Italy | Standardized care implemented of paediatric guidelines vs. historical control in ED | Two years with protocol (E) vs. previous 2 years in one hospital | 470 (C) vs. 603 (E) | 72% reduction in unexplained syncope 54% reduction in admissions |

| Source . | Intervention . | Comparison setting . | Number of patients . | Main results (experimental vs. conventional group) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenny et al.12 UK | Day-case falls and syncope unit in adults | Bed day activity in hospitals with (E) vs. hospitals without day-care facility (C) | – | 64% reduction in admissions in hospital with falls and syncope |

| Brignole et al.13 Italy | In-hospital Syncope Unit within the Department of Cardiology | 6 hospitals with Syncope Unit (E) vs. 6 hospitals without (C) Syncope Unit | 274 (C) vs. 279 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope 8% reduction of tests 12% reduction in admissions |

| Farwell and Sulke14 UK | Diagnostic/management protocol for syncope | One year with protocol (E) vs. previous year in one hospital | 660 (C) vs. 421 (E) | 166% increase in costs per patient: despite improved diagnosis, inappropriate investigation and admission still occurred |

| Shen et al.15 USA | Syncope Unit in the ED | Rate of admission and diagnosis in patients randomized to Syncope Units (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 51 (C) vs. 52 (E) | 63% reduction in unexplained syncope 56% reduction in admissions |

| Blanc et al.16 France | Education of ED physicians on T-LOC/syncope | One year before (C) vs. 1 year after education (E) | 454 (C) vs. 524 (E) | 11% reduction in unexplained syncope −25% reduction in admissions |

| Brignole et al.17 Italy | Standardized care using ESC guidelines | 28 hospitals with standard care (C) vs. 19 with standardized care (E) | 929 (C) vs. 745 (E) | 25% reduction in unexplained syncope 24% reduction of tests 17% reduction in admissions 19% reduction of costs per patient |

| Parry et al.18 UK | Education through management algorithm for acute medical services; effect on patient admitted for falls and syncope | One-month period before (C) vs. 1-month period a year later (E) | 41 (C) vs. 31 (E) | 2% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| Ammirati et al.19 Italy | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope referred to Syncope Unit; period before patients visited Syncope Unit (C) vs. after visit (E) | 96 | 82% reduction in unexplained syncope −85% reduction of costs per patient |

| Fedorowski et al.20 Sweden | Syncope Unit | Unexplained syncope patients discharged from ED or hospital ward (C) vs. the same patients evaluated by SU (E) | 101 | 87% reduction in unexplained syncope |

| McCarthy et al.21 Ireland | Using ESC Guidelines | Utilization of resources in ED (C) vs. re-evaluation of same patients using ESC guidelines; 6-month period | 214 | 54% reduction in admissions |

| Daccarett et al.22 USA | ESC Guidelines incorporated in ‘Faint-Algorithm’ | Retrospective assessment of ED admissions | 254 | 52% reduction in admissions |

| Shin et al.23 South Korea | Standardized ED protocol for syncope based on ESC guidelines | Period before (C) and after (E) standardization | 116 (C) vs. 128 (E) | 28% reduction in unexplained syncope 39% reduction in admissions 32% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sun24 USA | Up to 24 h observation ED | ED syncope presentation with usual care (C) or observation period (E) for intermediate-risk patients | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 42% reduction of costs per patient |

| Sanders et al.25 USA | Standardized care implemented in Faint and Fall Clinic vs. historical control | Standardized care (E) vs. historical control (C) | 100 (C) vs. 154 (E) | 22% reduction in unexplained syncope 80% reduction in admissions |

| Sun et al.26 USA | Observation Unit in five EDs | Rate of admission and costs in patients >50 years, randomized to observation unit (E) vs. standard of care (C) | 62 (C) vs. 62 (E) | 84% reduction in admissions 629 $ reduction in index hospital costs |

| Raucci et al.27 Italy | Standardized care implemented of paediatric guidelines vs. historical control in ED | Two years with protocol (E) vs. previous 2 years in one hospital | 470 (C) vs. 603 (E) | 72% reduction in unexplained syncope 54% reduction in admissions |

E, experimental group; C, control group; ED, Emergency Department.

Despite the recommendation from the ESC,2,3 SUs are not widely established in clinical practice. Possible reasons for this are outlined in Table 2. Barriers to establishing an SU include lack of resources, lack of trained dedicated staff, and complex presentations to multiple settings, necessitating involvement from multiple disciplines. When developing a case of need for the SU, individual practices may not be able to access detailed information to inform fully the economic cost and resource requirements necessary and this can make the justification for realignment of resources challenging. This document will assist practitioners to develop a model best suited to local requirements.

Syncope Unit reduces underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of syncope

An Internet search of the phrase ‘Misdiagnosis of Syncope’, reveals about equal numbers of search hits from three perspectives: those who approach the problem from the perspective of the over diagnosis of epilepsy,28 the underdiagnosis of syncope,29 or legal firms soliciting business from victims of either. When it comes to the underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of syncope, are estimated to be as high as 40%.17,28–32 Underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis have been reported in both outpatient and emergency settings. Although there are no large-scale randomized trials comparing misdiagnosis of syncope in SUs to usual care, smaller cohort studies confirm high rates of misdiagnosis with usual care and the benefits of a structured approach to diagnosis.9,17,20,33

Syncope Unit reduces hospitalization

In hospitals without an SU, T-LOC evaluation and management is more frequently carried out as an inpatient rather than an outpatient service. In other words, patients are preferentially admitted to emergency services rather than evaluated and managed as outpatients (Table 3). In one study, the average length of stay for acute admissions due to syncope or collapse was two-fold higher in hospitals without an SU.12,15,34,35

The Syncope Evaluation in the Emergency Department Study (SEEDS)15 randomized intermediate-risk patients to an Emergency Department (ED)-based explicit syncope protocol vs. routine inpatient admission. Hospital admissions were reduced by 56%, and total patient-hospital days were reduced by 54%. In the Emergency Department Observation Syncope Protocol (EDOSP) trial,26 patients randomized to an ED observation protocol experienced a 77% reduction in hospitalization and a 40% reduction in hospital length of stay.26 An integrated model of Short Observation stay in ED, coupled with fast track to an SU allowed a reduction of the admission rate to 29% with 20% of patients being dicharged after a short observation in ED, 20% fast-tracked to the SU and 31% directly discharged.36

Syncope Unit reduces cost of syncope

Cost estimates

Several studies investigated costs of syncope as they appear in national or hospital records (Table 3).24,34,37,38 In the USA, in 2004, the mean cost for a syncope-related admission was $5400 (95% CI: $5100–5600) with a total annual cost of $2.4 billion,32 similar to asthma ($2.8 billion) and HIV ($2.2 billion). In Italy, in 2006,17 the mean cost for a syncope-related admission was €2785 ± 2168; hospital costs accounted for about three quarters of total costs. The cost per patient discharged from ED was €180 ± 63. In Spain, in 2006,9 the overall cost (which included stay, diagnosis, and treatment) per admitted patient was €11 158 (range: 1651–31 762). In the outpatient setting, the cost is similarly alarmingly high due to significant variability in practice and the use of unnecessary tests.6,19,39 In one study,40 patients with unexplained syncope had a median of 13 non-diagnostic tests performed (range: 9–20) before receiving an implantable loop recorder.

Cost reductions

Various hospitals organized syncope care through the creation of SUs, where a solid conceptual framework with clearly delineated diagnostic procedures is implemented. The primary outcome was an increase in the rate of diagnostic yield,1–3 and a reduction in costs primarily by reducing the number of admissions, duration of hospital stay, and the number of unnecessary tests,12,13,15,17,19,21–23,25,41,42 with few exceptions.14 Indeed, Brignole et al.17 have shown a 19% reduction in cost per patient and a 29% reduction in cost per diagnosis in the standardized care group when compared with the conventional approach. The EDOSP randomized trial26 included an explicit cost analysis. Hospital facility costs were $629 less in the observation unit group compared with the routine admission group. Rates of diagnostic testing and specialty consultation were similar in both groups; therefore, cost savings were due to reduction in hospital length-of-stay.

Expected benefit

Establishing an SU should benefit three parties: (i) patients by increasing the rate of correct diagnosis, (ii) health payers by reducing total cost per patient and diagnosis, and (iii) hospitals by increasing their market share via the added value proposition. In healthcare systems based on payment per test or per medical action, an SU may reduce income through a reduction of tests. The expected benefit should focus on improved healthcare. There may be cost savings, but these will be system dependent and thus vary. The cost benefit of a syncope specialist or an SU in different settings and different healthcare systems has not been exposed to rigorous economic and scientific scrutiny. Further research is required to determine resource outcomes and the authors acknowledge the limitations of the current knowledge base and recognize that service models may be influenced by local circumstances.

Structure of European Heart Rhythm Association Syncope Unit

Existing models for syncope management

Syncope management organization may differ widely among healthcare systems and from hospital to hospital. A review of published data on organization and impact on outcomes of models of care may guide SU design and implementation for a given environment. Table 4 summarizes these data. We acknowledge that overlap exists between these models.

Various existing models for syncope management from published data of comparison between systematic evaluation and conventional management in controlled studies

| . | The functional Syncope Unit in a cardiology department . | The Day-Care Syncope Evaluation Unit and Fall and Syncope Services . | The Rapid Access Blackouts Triage Clinic (T-LOC Triage Clinic) . | Tertiary referral SU . | The Syncope Observational Unit in the ED . | The web-based standardized care pathway for Faint and Fall patients (Faint and Fall Clinic) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | 13,17,20,25,36,39,41,43–45 | 12,35,46 | 47,48 | 49,50 | 15,26,51 | 5,25 |

| Location | Cardiology department/outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | ED | Outpatient clinic |

| Management | Cardiologist with rapid access to other specialists | Geriatrician/internist | Specialized nurses (arrhythmias, falls, epilepsy) Supervision: cardiologist/neurologist | One syncope specialist (neurologist, internist, cardiologist) | Experienced emergency physician | Cardiologist and geriatrician with rapid access to a neurologist |

| Support | Trained nurses | Other specialists and general practitioners, specialized nurses | Cardiologists | Technicians, specialized nurses | Specialized nurses, electrophysiologist's, other specialists | Nurse practitioner |

| Referral | Outpatients, fast track from ED, other departments | Community, ED, other departments | General practitioners, specialists (cardiology, neurology), ED | Most referrals from cardiologists and neurologists | ED (only intermediate risk patients were included in the SEEDS and EDOSP studies) | Outpatients and ED |

| Organization | Functional unit in the hospital | Day-care multidisciplinary medical approach, specialized nurses | Rapid assessment outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | 6–24 h of observation | Fixed unit with rapid access |

| Tools | Guidelines-based flowcharts, software | Specialist visits, non-invasive tests, occupational activities | Web-based questionnaire | History taking, reappraisal of the case | ECG and BP monitoring, non-invasive tests and electrophysiologist's consultations. Rapid FU appointment if discharged | Web-based decision-making software |

| Core laboratory tests | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR and ELR, ambulatory BP monitoring | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR, and ELR | History, physical examination, ECG, ILR | TT, CSM, autonomic tests, ambulatory BP and ECG monitoring, ILR | Laboratory tests, CSM, TT | Cardiac imaging, stress tests, TT, CSM, electrophysiological study, Holter, ELR, and ILR |

| Impact on outcomes: methodology | Lowering of hospital admissions and costs, improvement of the diagnostic yield | Lowering of costs driven by hospital admissions and readmissions, improvement of the diagnostic yield and access to tests | Rapid diagnosis and triage, lowering of readmissions for T-LOCs | Compared with other SUs low rates of unexplained syncope and of cardiac syncope, high rates of psychogenic pseudosyncope and complex reflex syncope | Higher and earlier number of suspected diagnosis, lower hospital admissions and patient-hospital days | Decrease in hospital admissions, higher rate of diagnosis at 45 days, less utilization of costly tests and consultations |

| . | The functional Syncope Unit in a cardiology department . | The Day-Care Syncope Evaluation Unit and Fall and Syncope Services . | The Rapid Access Blackouts Triage Clinic (T-LOC Triage Clinic) . | Tertiary referral SU . | The Syncope Observational Unit in the ED . | The web-based standardized care pathway for Faint and Fall patients (Faint and Fall Clinic) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | 13,17,20,25,36,39,41,43–45 | 12,35,46 | 47,48 | 49,50 | 15,26,51 | 5,25 |

| Location | Cardiology department/outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | ED | Outpatient clinic |

| Management | Cardiologist with rapid access to other specialists | Geriatrician/internist | Specialized nurses (arrhythmias, falls, epilepsy) Supervision: cardiologist/neurologist | One syncope specialist (neurologist, internist, cardiologist) | Experienced emergency physician | Cardiologist and geriatrician with rapid access to a neurologist |

| Support | Trained nurses | Other specialists and general practitioners, specialized nurses | Cardiologists | Technicians, specialized nurses | Specialized nurses, electrophysiologist's, other specialists | Nurse practitioner |

| Referral | Outpatients, fast track from ED, other departments | Community, ED, other departments | General practitioners, specialists (cardiology, neurology), ED | Most referrals from cardiologists and neurologists | ED (only intermediate risk patients were included in the SEEDS and EDOSP studies) | Outpatients and ED |

| Organization | Functional unit in the hospital | Day-care multidisciplinary medical approach, specialized nurses | Rapid assessment outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | 6–24 h of observation | Fixed unit with rapid access |

| Tools | Guidelines-based flowcharts, software | Specialist visits, non-invasive tests, occupational activities | Web-based questionnaire | History taking, reappraisal of the case | ECG and BP monitoring, non-invasive tests and electrophysiologist's consultations. Rapid FU appointment if discharged | Web-based decision-making software |

| Core laboratory tests | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR and ELR, ambulatory BP monitoring | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR, and ELR | History, physical examination, ECG, ILR | TT, CSM, autonomic tests, ambulatory BP and ECG monitoring, ILR | Laboratory tests, CSM, TT | Cardiac imaging, stress tests, TT, CSM, electrophysiological study, Holter, ELR, and ILR |

| Impact on outcomes: methodology | Lowering of hospital admissions and costs, improvement of the diagnostic yield | Lowering of costs driven by hospital admissions and readmissions, improvement of the diagnostic yield and access to tests | Rapid diagnosis and triage, lowering of readmissions for T-LOCs | Compared with other SUs low rates of unexplained syncope and of cardiac syncope, high rates of psychogenic pseudosyncope and complex reflex syncope | Higher and earlier number of suspected diagnosis, lower hospital admissions and patient-hospital days | Decrease in hospital admissions, higher rate of diagnosis at 45 days, less utilization of costly tests and consultations |

BP, blood pressure; CSM, carotid sinus massage; TT, tilt table test; ILR, implantable loop recorder; ELR, external loop recorder; T-LOC, transient loss of consciousness; ED, emergency department; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Various existing models for syncope management from published data of comparison between systematic evaluation and conventional management in controlled studies

| . | The functional Syncope Unit in a cardiology department . | The Day-Care Syncope Evaluation Unit and Fall and Syncope Services . | The Rapid Access Blackouts Triage Clinic (T-LOC Triage Clinic) . | Tertiary referral SU . | The Syncope Observational Unit in the ED . | The web-based standardized care pathway for Faint and Fall patients (Faint and Fall Clinic) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | 13,17,20,25,36,39,41,43–45 | 12,35,46 | 47,48 | 49,50 | 15,26,51 | 5,25 |

| Location | Cardiology department/outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | ED | Outpatient clinic |

| Management | Cardiologist with rapid access to other specialists | Geriatrician/internist | Specialized nurses (arrhythmias, falls, epilepsy) Supervision: cardiologist/neurologist | One syncope specialist (neurologist, internist, cardiologist) | Experienced emergency physician | Cardiologist and geriatrician with rapid access to a neurologist |

| Support | Trained nurses | Other specialists and general practitioners, specialized nurses | Cardiologists | Technicians, specialized nurses | Specialized nurses, electrophysiologist's, other specialists | Nurse practitioner |

| Referral | Outpatients, fast track from ED, other departments | Community, ED, other departments | General practitioners, specialists (cardiology, neurology), ED | Most referrals from cardiologists and neurologists | ED (only intermediate risk patients were included in the SEEDS and EDOSP studies) | Outpatients and ED |

| Organization | Functional unit in the hospital | Day-care multidisciplinary medical approach, specialized nurses | Rapid assessment outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | 6–24 h of observation | Fixed unit with rapid access |

| Tools | Guidelines-based flowcharts, software | Specialist visits, non-invasive tests, occupational activities | Web-based questionnaire | History taking, reappraisal of the case | ECG and BP monitoring, non-invasive tests and electrophysiologist's consultations. Rapid FU appointment if discharged | Web-based decision-making software |

| Core laboratory tests | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR and ELR, ambulatory BP monitoring | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR, and ELR | History, physical examination, ECG, ILR | TT, CSM, autonomic tests, ambulatory BP and ECG monitoring, ILR | Laboratory tests, CSM, TT | Cardiac imaging, stress tests, TT, CSM, electrophysiological study, Holter, ELR, and ILR |

| Impact on outcomes: methodology | Lowering of hospital admissions and costs, improvement of the diagnostic yield | Lowering of costs driven by hospital admissions and readmissions, improvement of the diagnostic yield and access to tests | Rapid diagnosis and triage, lowering of readmissions for T-LOCs | Compared with other SUs low rates of unexplained syncope and of cardiac syncope, high rates of psychogenic pseudosyncope and complex reflex syncope | Higher and earlier number of suspected diagnosis, lower hospital admissions and patient-hospital days | Decrease in hospital admissions, higher rate of diagnosis at 45 days, less utilization of costly tests and consultations |

| . | The functional Syncope Unit in a cardiology department . | The Day-Care Syncope Evaluation Unit and Fall and Syncope Services . | The Rapid Access Blackouts Triage Clinic (T-LOC Triage Clinic) . | Tertiary referral SU . | The Syncope Observational Unit in the ED . | The web-based standardized care pathway for Faint and Fall patients (Faint and Fall Clinic) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | 13,17,20,25,36,39,41,43–45 | 12,35,46 | 47,48 | 49,50 | 15,26,51 | 5,25 |

| Location | Cardiology department/outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | ED | Outpatient clinic |

| Management | Cardiologist with rapid access to other specialists | Geriatrician/internist | Specialized nurses (arrhythmias, falls, epilepsy) Supervision: cardiologist/neurologist | One syncope specialist (neurologist, internist, cardiologist) | Experienced emergency physician | Cardiologist and geriatrician with rapid access to a neurologist |

| Support | Trained nurses | Other specialists and general practitioners, specialized nurses | Cardiologists | Technicians, specialized nurses | Specialized nurses, electrophysiologist's, other specialists | Nurse practitioner |

| Referral | Outpatients, fast track from ED, other departments | Community, ED, other departments | General practitioners, specialists (cardiology, neurology), ED | Most referrals from cardiologists and neurologists | ED (only intermediate risk patients were included in the SEEDS and EDOSP studies) | Outpatients and ED |

| Organization | Functional unit in the hospital | Day-care multidisciplinary medical approach, specialized nurses | Rapid assessment outpatient clinic | Outpatient clinic | 6–24 h of observation | Fixed unit with rapid access |

| Tools | Guidelines-based flowcharts, software | Specialist visits, non-invasive tests, occupational activities | Web-based questionnaire | History taking, reappraisal of the case | ECG and BP monitoring, non-invasive tests and electrophysiologist's consultations. Rapid FU appointment if discharged | Web-based decision-making software |

| Core laboratory tests | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR and ELR, ambulatory BP monitoring | CSM, TT with beat-to-beat measurement, ILR, and ELR | History, physical examination, ECG, ILR | TT, CSM, autonomic tests, ambulatory BP and ECG monitoring, ILR | Laboratory tests, CSM, TT | Cardiac imaging, stress tests, TT, CSM, electrophysiological study, Holter, ELR, and ILR |

| Impact on outcomes: methodology | Lowering of hospital admissions and costs, improvement of the diagnostic yield | Lowering of costs driven by hospital admissions and readmissions, improvement of the diagnostic yield and access to tests | Rapid diagnosis and triage, lowering of readmissions for T-LOCs | Compared with other SUs low rates of unexplained syncope and of cardiac syncope, high rates of psychogenic pseudosyncope and complex reflex syncope | Higher and earlier number of suspected diagnosis, lower hospital admissions and patient-hospital days | Decrease in hospital admissions, higher rate of diagnosis at 45 days, less utilization of costly tests and consultations |

BP, blood pressure; CSM, carotid sinus massage; TT, tilt table test; ILR, implantable loop recorder; ELR, external loop recorder; T-LOC, transient loss of consciousness; ED, emergency department; ECG, electrocardiogram.

A functional Syncope Unit located in a cardiology department13,17,20,25,39,43–45

In this model, introduced in Italy and adopted in other countries such as Sweden, Portugal, USA, and France, the SU is supervised by cardiologists, supported by dedicated personnel with expertise in syncope. Patients access the SU mainly as outpatient or via the emergency room. This model has evolved into a ‘virtual’ unit based on the expertise of a limited team and in some instances on web-based decision-making software.52 Access to a specialist is regarded as essential. A specialist can be accessed by any means, e.g. telephone. The Evaluation of Guidelines in SYncope Study-2 (EGSYS-2)17 showed a sharp decrease in the overall cost of care driven by a reduction in average cost per patient of 19% and average cost per diagnosis of 29%. Seventy-one Italian hospitals now have an SU that has been certified by peer-review members of GIMSI (Gruppo Italiano Multidisciplinare per lo studio della Sincope, www.gimsi.it). Similar models have been described in other departments, e.g. geriatric and internal medicine; the organization is basically the same with formalized fast-tracking processes to cardiological testing. In a few instances, the SU includes also a short observation stay as part of an internal protocol for risk stratification of intermediate risk ED patients.36

The Day-Care Syncope Evaluation Unit and the Falls and Syncope Services

This model was first developed in Newcastle, UK12 and takes the form of an outpatient, day-care facility located in a general hospital. The service provides a multidisciplinary approach based on the application of evidence-based diagnostic algorithms to patients with falls (for older patients) and T-LOC of suspected syncopal nature (all adult age groups). Close liaison exists with acute medical in-patient and ED services. After a consultation with an emergency physician, geriatrician, internist, or general practitioner, patients have access to non-invasive diagnostic testing, occupational and physiotherapy, and supplementary examinations supported by specialist nurses. There is close cooperation and consultation with cardiology and neurology services for further diagnostics and treatments. In line with this experience, Falls and Syncope Services for older people have evolved by defining protocols and educational methods for inpatients35 and outpatients.46

The Rapid Access Blackouts Clinic

This type of SU functions as a ‘referral centre’ for patients with T-LOC.47,48 As such, it is positioned between first response and specialist referrals. It is led jointly by a cardiologist and a neurologist. The aim is to provide rapid access to clinical and ECG assessment in order to screen patients. The SU is run by nurses specialized in epilepsy, cardiac arrhythmias, or geriatrics. Patients referred by general practitioners or emergency services complete a triage questionnaire: 60 standard questions/data detailing characteristics of falls, syncope, and epilepsy, which is analysed by the nurses. A cardiologist may be consulted for interpretation of tests, notably the ECG. Following this evaluation, patients are referred, as appropriate, to a cardiologist, neurologist, geriatrician, general practitioner, or psychologist. Continuity of care is ensured by maintaining and sharing a database for all stakeholders.

Tertiary referral Syncope Unit49,53

This model is centred on one syncope specialist, a neurologist, internist, or cardiologist, who mostly sees tertiary T-LOC referrals from neurologists and cardiologists. The SU consists of an outpatient clinic and a core laboratory performing tilt table test, carotid sinus massage, cardiovascular autonomic tests, and ambulatory BP monitoring. The tertiary character means that other ancillary tests have already been performed, and that the case mix concerns low rates of cardiac syncope and of unexplained syncope, but high rates of reflex syncope, psychogenic pseudosyncope, and epilepsy (see ‘Competence’ section).

The Syncope Observational Unit in the Emergency Department

This type of SU is described in the SEEDS study.15 This single-centre prospective randomized study evaluated a standardized unit incorporated in the ED of a university tertiary care hospital, compared with conventional care, in a group of syncope patients considered to be at ‘intermediate’ cardiovascular risk. After 6 h of monitoring and tests in the ED which included regular orthostatic blood pressure measurements, tilt table test and carotid sinus massage upon physician's request and electrophysiologist's consultation when requested, patients without indication for hospitalization were offered rapid outpatient follow-up consultation. This study showed, in 51 consecutive patients randomized to SU evaluation, an improvement in diagnostic yield compared with conventional care (67 vs. 10%) and a decrease in hospital admission (43 vs. 98%), but no changes in the average length of stay. The model did not reduce 2-year mortality nor syncopal recurrences.

Using a protocol with an initial evaluation similar to that described in the ESC Guidelines and an observational unit, for up to 24 h, within the ED, a Spanish group has achieved a diagnosis in 78% of patients presenting as emergencies with only 10% of syncope patients being admitted to hospital in this model.51

Recently, the EDOSP study26 evaluated an ED observation protocol at five sites, including university, community, and public hospitals. Patients at ‘intermediate’ risk were randomized either to an explicit ED-based observational unit protocol vs. routine care. The observational unit protocol included up to 24 h of cardiac monitoring and echocardiogram for selected patients. In 124 randomized patients, there were reductions in hospitalizations rate (15 vs. 92%), length-of-stay (29 vs. 47 h), and hospital costs were $629 lower than the admission group. There were no differences in safety events (i.e. serious 30-day outcomes occurring after hospital discharge), quality-of-life, or costs. The EDOSP study generalizes the SEEDS findings to a diverse set of hospitals, and includes novel assessments of patient-centred outcomes and a formal economic analysis.

The Faint and Fall Clinic

The Faint and Fall Clinic offers a multidisciplinary approach to patients presenting with fainting spells or falls. Patients are evaluated by advanced nurse practitioners and then seen by a cardiologist or a geriatrician with rapid access to a neurologist, as needed. Providers in the clinic use a web-based interactive software that integrates the most recent guidelines for risk assessment and management of patients with T-LOC.5,25

Current situation

The UK has a growing number of SUs, which are listed by STARS (Syncope Trust and Anoxic Reflex Seizures), a charitable organization providing information to patients about syncope and related conditions, www.stars.org. Italy has a growing number of SUs which are listed by GIMSI (Gruppo Italiano Multidisciplinare per lo studio della Sincope), www.gimsi.it. These information sites include available SUs that are geographically close to the enquiring patient. In Ireland, USA, Canada, Spain, Portugal, France, Netherlands, Sweden, Japan, Brazil, Romania, Poland, Slovakia, and other countries there are similar developments.

In summary, whatever the SU model, the key elements are rapid access to syncope expertise in trained, dedicated staff, together with the utilization of standardized algorithms. The European Heart Rhythm Association considers that SUs should be widely available in Europe. Their aims and structure should be in line with one or other of the models reported permits each hospital to develop their own model to suit its particular environment.

General attributes of a Syncope Unit

The SU can be virtual or based on a pre-defined location such as a unit associated with the ED, an ambulatory clinic, or employs a combination of approaches. The model of SU should be the best fit for local practice. Because of the extensive differential diagnoses and high prevalence of syncope in older patients, the skill mix of SU staff should include some training/knowledge of common disorders that cause or mimic syncope: commonly cardiovascular, neurologic, geriatric, and psychiatric disorders.

As no single syncope care service model is suitable for all healthcare systems, the following is a list of some of the important features to consider when establishing an SU:

Structure of SU

◯ The model of care delivery should be appropriate to local resources and local specialities while ensuring implementation of published practice guidelines.

◯ Models of care delivery vary from a single one-site-one-stop syncope facility to a wider multifaceted practice in which several specialists are involved in syncope management.

◯ The SU can be a single site facility or virtual model with mobile team.

Stakeholders

◯ All key stakeholders should be involved in the earliest stages of development and implementation of the SU.

It is essential to establish a mechanism through which regular communication can be established with all stakeholders (i.e. patients, referring physicians, hospital/clinic management, consultant physicians, nurses, and other allied medical professionals) in order to ensure an ongoing consensus for and understanding of proposed management strategies. This mechanism includes the implications of and implementation of published guidelines. Stakeholders may be staff from the ED, neurology, general internal medicine, orthopaedic surgery, geriatric medicine, psychiatry, and ear, nose, and throat (ENT), paediatric departments in addition to cardiology.

This should also include agreed measurement metrics of performance in order that early recognition of variation is achieved; thereby re-calibration of the model can take place in a timely fashion. These measures should include outcome measures, process measures, and balancing measures.

A clear diagnostic and therapeutic pathway provides a framework, which is fundamental to enable new evidence to be incorporated into the model seamlessly.

Management

◯ The management strategy should be agreed on and practiced by all practitioners (encompassing a range of specialities) involved in syncope management.

Patient case mix

◯ The age range and symptom characteristics of patients appropriate for syncope investigation should be determined in advance. Some facilities are prepared to evaluate both paediatric and adult patients, whereas others limit practice to adult or paediatric cases. A wide age range is encouraged.

Referral sources

◯ Potential referral sources should be taken into consideration. Referral can be directly from family practitioners, from the ED, from occupational physicians, from hospital admissions, and from patients in institutional settings. The scope of referral source has implications for resources and skill mix.

SU—skill mix and staffing

◯ There are existing models in which cardiologists (commonly with an interest in cardiac pacing and electrophysiology), neurologists (commonly with an interest in autonomic disorders and/or epilepsy), internists (commonly with an interest in cardiovascular physiology and autonomic disorders), emergency doctors, and geriatricians (commonly with an interest in age-related cardiology or falls) each may lead syncope facilities. There is no evidence for superiority of any model.

◯ The skill mix (i.e. the types of professional/specialities) required to staff the facility depends on the extent to which screening of referrals occurs before presentation at the facility. For example, if referrals are directly from the community a broader skill mix than cardiology is required. Under these circumstances, other disorders such as epilepsy, autonomic disorders, neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic disorders, and falls are also common.

◯ When establishing a unit the lead clinician should have knowledge of the catchment area for referrals and projected volume in order to estimate staff requirements and to tailor the scope of referrals to available resources. The volume of activity and the number of personnel largely vary based on the model of SU and local organization. No empirical figures can therefore be given. However, since the aim of this document is to provide practical advice to stakeholders who are interested in setting-up an SU, as a general guide, this Task Force believes that the following figures should be of help. In the Italian experience,41 163 patients per 100 000 inhabitants per year were referred to the local SU. They performed an average of 2.9 tests per patient. Patients will be followed-up from a minimum of one to multiple visits. Multiple visits (on-site or by means of telemedicine) were necessary especially in the case of patients with unexplained syncope undergoing prolonged monitoring or patients who had received device therapies (pacemaker clinic, etc.). Thus, this Task Force estimates that one syncope specialist and one technician need to work the equivalent of one full working day per week for every 100 000 inhabitants of the catchment area.

◯ SU staff should provide ongoing education and training in syncope diagnosis, investigation and management to primary and secondary care colleagues who deal with this symptom in their day-to-day practice.

Structure of the European Heart Rhythm Association Syncope Unit

The proposed structure of the EHRA SU is shown in the Consensus Statement 1. The role of physician and staff in performing procedures and tests is shown in Table 5.

| Procedure or test . | SU physician . | SU staff . | Non-SU personnel . |

|---|---|---|---|

| History taking | x | ||

| Structured history taking (e.g. application of software technologies and algorithms) | x | ||

| 12-Lead ECG | x | ||

| Blood tests | x | ||

| Echocardiogram and imaging | x | ||

| Carotid sinus massage | x | ||

| Active standing test | x | ||

| Tilt table test | xa | x | |

| Basic autonomic function test | x | x | |

| ECG monitoring (Holter, external loop recorder): administration and interpretation | x | x | |

| Implantable loop recorder | x | xb | |

| Remote monitoring | x | ||

| Other cardiac tests (stress test, electrophysiological study, angiograms) | x | ||

| Neurological tests (CT, MRI, EEG, video-EEG) | x | ||

| Pacemaker and ICD implantation, catheter ablation | x | ||

| Patient's education, biofeedback trainingc. and instruction sheet on counter pressure manoeuvres | x | x | |

| Final report and clinic note | x | ||

| Communication with patients, referring physicians and stakeholders | x | x | |

| Follow-up | x | x |

| Procedure or test . | SU physician . | SU staff . | Non-SU personnel . |

|---|---|---|---|

| History taking | x | ||

| Structured history taking (e.g. application of software technologies and algorithms) | x | ||

| 12-Lead ECG | x | ||

| Blood tests | x | ||

| Echocardiogram and imaging | x | ||

| Carotid sinus massage | x | ||

| Active standing test | x | ||

| Tilt table test | xa | x | |

| Basic autonomic function test | x | x | |

| ECG monitoring (Holter, external loop recorder): administration and interpretation | x | x | |

| Implantable loop recorder | x | xb | |

| Remote monitoring | x | ||

| Other cardiac tests (stress test, electrophysiological study, angiograms) | x | ||

| Neurological tests (CT, MRI, EEG, video-EEG) | x | ||

| Pacemaker and ICD implantation, catheter ablation | x | ||

| Patient's education, biofeedback trainingc. and instruction sheet on counter pressure manoeuvres | x | x | |

| Final report and clinic note | x | ||

| Communication with patients, referring physicians and stakeholders | x | x | |

| Follow-up | x | x |

CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SU, Syncope Unit.

aPhysician need not be in the room, but a physician adequately trained in resuscitation needs to be in the area of the test.

bCurrent practice limited to few countries.

cBiofeedback means that the training session of the counter pressure manoeuvres consists of biofeedback training using a continuous blood pressure monitor. Each manoeuvre is demonstrated and explained. The manoeuvres are practiced under supervision, with immediate feedback of the recordings to gain optimal performance.54

| Procedure or test . | SU physician . | SU staff . | Non-SU personnel . |

|---|---|---|---|

| History taking | x | ||

| Structured history taking (e.g. application of software technologies and algorithms) | x | ||

| 12-Lead ECG | x | ||

| Blood tests | x | ||

| Echocardiogram and imaging | x | ||

| Carotid sinus massage | x | ||

| Active standing test | x | ||

| Tilt table test | xa | x | |

| Basic autonomic function test | x | x | |

| ECG monitoring (Holter, external loop recorder): administration and interpretation | x | x | |

| Implantable loop recorder | x | xb | |

| Remote monitoring | x | ||

| Other cardiac tests (stress test, electrophysiological study, angiograms) | x | ||

| Neurological tests (CT, MRI, EEG, video-EEG) | x | ||

| Pacemaker and ICD implantation, catheter ablation | x | ||

| Patient's education, biofeedback trainingc. and instruction sheet on counter pressure manoeuvres | x | x | |

| Final report and clinic note | x | ||

| Communication with patients, referring physicians and stakeholders | x | x | |

| Follow-up | x | x |

| Procedure or test . | SU physician . | SU staff . | Non-SU personnel . |

|---|---|---|---|

| History taking | x | ||

| Structured history taking (e.g. application of software technologies and algorithms) | x | ||

| 12-Lead ECG | x | ||

| Blood tests | x | ||

| Echocardiogram and imaging | x | ||

| Carotid sinus massage | x | ||

| Active standing test | x | ||

| Tilt table test | xa | x | |

| Basic autonomic function test | x | x | |

| ECG monitoring (Holter, external loop recorder): administration and interpretation | x | x | |

| Implantable loop recorder | x | xb | |

| Remote monitoring | x | ||

| Other cardiac tests (stress test, electrophysiological study, angiograms) | x | ||

| Neurological tests (CT, MRI, EEG, video-EEG) | x | ||

| Pacemaker and ICD implantation, catheter ablation | x | ||

| Patient's education, biofeedback trainingc. and instruction sheet on counter pressure manoeuvres | x | x | |

| Final report and clinic note | x | ||

| Communication with patients, referring physicians and stakeholders | x | x | |

| Follow-up | x | x |

CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SU, Syncope Unit.

aPhysician need not be in the room, but a physician adequately trained in resuscitation needs to be in the area of the test.

bCurrent practice limited to few countries.

cBiofeedback means that the training session of the counter pressure manoeuvres consists of biofeedback training using a continuous blood pressure monitor. Each manoeuvre is demonstrated and explained. The manoeuvres are practiced under supervision, with immediate feedback of the recordings to gain optimal performance.54

Consensus Statement 1—Structure of the EHRA SU

Staffing of an SU is composed of:

|

Facility, protocol, and equipment

|

Therapy

|

Database management

|

Staffing of an SU is composed of:

|

Facility, protocol, and equipment

|

Therapy

|

Database management

|

aImplantation of loop recorders may be performed either by SU physicians or by external cardiologists upon request of the SU physicians.

Consensus Statement 1—Structure of the EHRA SU

Staffing of an SU is composed of:

|

Facility, protocol, and equipment

|

Therapy

|

Database management

|

Staffing of an SU is composed of:

|

Facility, protocol, and equipment

|

Therapy

|

Database management

|

aImplantation of loop recorders may be performed either by SU physicians or by external cardiologists upon request of the SU physicians.

The ‘syncope specialist’

The syncope specialist has responsibility for the comprehensive management of the patient from risk stratification to diagnosis, therapy, and follow-up, through a standardized protocol. The syncope specialist requires specific knowledge. The domains required are listed in the ‘Competence’ section.

The staff

Most of the work is undertaken by nursing/technical staff. This requires specific skill and competence. In addition to assisting the syncope specialist, the specialized nurse/technician will perform procedures and tests (under physician supervision) provided that they are based on internal protocols and rules (Table 5).

Competence

Considerations

Defining the area and level of competence of an SU is based on the following assumptions. Even if the skill of an individual syncope specialist may be insuffcient to cover the whole case mix of the SU, the multidisciplinary skill of the different specialists involved in the SU should potentially be competent in are all disorders referred to as T-LOC.

At present, the field lacks structured accreditation for clinical skills of the clinicians, and additional staff as well as equipment and facilities in the SU. The authors anticipate that this Position Paper will stimulate new structured training and accreditation opportunities. A diploma course, ‘Syncope and Related disorders’ for international participants, awarded by the Royal College of Physicians in Dublin, Ireland, is one example (www.rcpi.ie).

Disorders causing T-LOC are diverse and are reported to occur at different rates illustrtaing the scope of the necessary competencies. Results of 10 SUs13,17,19,23,41,45,55,56 (W. Wieling and J.G. van Dijk, personal communication) yielded the following categories (mean and range): reflex syncope (59%, 46–68), cardiac (10%, 1–35), orthostatic hypotension (9%, 1–19), unexplained syncope (11%, 5–18), psychogenic pseudosyncope (4%, 0–12), and epileptic seizures (1%, 0–5). Reflex syncope is by far the most common diagnosis. The rates of other disorders vary considerably, probably the result of differences in setting and specialty, and perhaps of limited diagnostic skills.

A second factor determining competence is risk management: the risks of cardiac syncope are high, those of reflex syncope low, with epilepsy, orthostatic hypotension and psychogenic T-LOC being intermediate. High risks require higher diagnostic skill levels regardless of frequency.

Thirdly, patient age affects the scope of competence. Syncope Units focusing on the elderly will encounter a different set of disorders compared with those with paediatric patients.46 While paediatric T-LOC/syncope is not covered in depth by the 2009 ESC guidelines, the basic approach is the same as in adults, and children with T-LOC may profit as much from an SU as adults.

Syncope specialist

The considerations above prompted the following pragmatic description of a syncope specialist. A syncope specialist is a physician who has sufficient knowledge of historical clues and physical findings to recognize all major T-LOC forms, including mimics, as well as syndromes of orthostatic intolerance.

Syncope specialists need not all have the same skill levels, but the SU as a whole must be able to provide a minimum skill set, so a combination of specialty skills is optimal. These conclusions are specified in Consensus Statement 2—Competence and skills mix of physicians and staff required for syncope management in an SU.

Notes on training

Syncope specialists typically start working in an SU after specialty training, so knowledge regarding T-LOC forms not covered by their specialty may need to be refreshed. Reflex syncope, orthostatic intolerance, and psychogenic pseudosyncope deserve special attention, as they usually do not routinely feature in prior training.

Reflex syncope is frequent in the population (30–40%) and in SUs (59%). Mastering the diagnosis of reflex syncope is difficult because its signs and symptoms are so variable that syncope cannot be defined practically using clinical descriptors: the ESC Guidelines defined T-LOC clinically but not syncope.57 No ancillary test for reflex syncope meets the requirements,58 leaving history taking as the prime diagnostic instrument. The importance of history taking and its high diagnostic yield49 means that history taking should be allowed time. Syncope specialists typically set aside more time for history taking than novices, and may need up to 60 min to take a history and explain a diagnosis.58–62 As for risk prediction, rule sets did not perform better than clinical judgement.63 A thorough knowledge of circulatory physiology helps to attribute historical elements to known circulatory patterns, strengthened by tilt table test experience.64,65 Psychogenic pseudosyncope occurs at vastly different frequencies in different studies. It can be recognized through history taking and often with tilt table testing.66 Video-EEG monitoring is a preferable addition, conforming to the gold standard approach for psychogenic non-epileptic seizures.

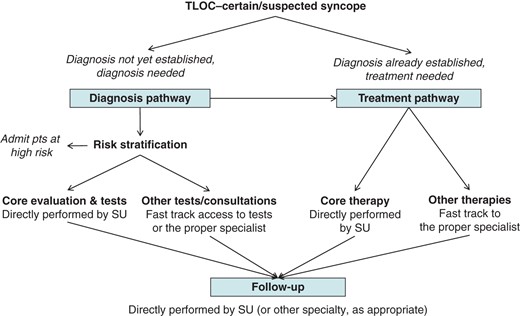

Framework for a comprehensive management of patients with T-LOC of certain/suspected syncopal nature referred to the SU. Core evaluation and therapy depend on each model of care delivery, with a minimum acceptable set described in Consensus Statement 1.

Consensus Statement 2—Competence and skills mix of physicians and staff required for syncope management in an SU

| Major and minor category . | 1. Diagnostic skills per syncope specialist . | 2. SU access to ancillary tests . | 3. SU ancillary tests . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syncope | |||

| Reflex | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, CSM, 24 h BP, ELR-ILR |

| Syncope due to OH | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, 24 h BP, autonomic testing |

| Cardiac syncope | Specialist knowledge | Full/preferential | ECG, telemetry, ELR-ILR, Echo, EPS |

| Epileptic seizures | |||

| General medical knowledge | Preferential | EEG, video-EEG monitoring, home video, neuroimaging | |

| Psychogenic T-LOC | |||

| PPS | General medical knowledge | Full/Preferential | TT, preferentially with video-EEG monitoring, home video |

| PNES | General medical knowledge | Preferential | video-EEG monitoring, home video |

| Major and minor category . | 1. Diagnostic skills per syncope specialist . | 2. SU access to ancillary tests . | 3. SU ancillary tests . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syncope | |||

| Reflex | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, CSM, 24 h BP, ELR-ILR |

| Syncope due to OH | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, 24 h BP, autonomic testing |

| Cardiac syncope | Specialist knowledge | Full/preferential | ECG, telemetry, ELR-ILR, Echo, EPS |

| Epileptic seizures | |||

| General medical knowledge | Preferential | EEG, video-EEG monitoring, home video, neuroimaging | |

| Psychogenic T-LOC | |||

| PPS | General medical knowledge | Full/Preferential | TT, preferentially with video-EEG monitoring, home video |

| PNES | General medical knowledge | Preferential | video-EEG monitoring, home video |

TT, tilt table test; CSM, carotid sinus massage; ILR, implantable loop recorder; ELR, external loop recorder; BP, blood pressure; Echo, echocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; OH, orthostatic hypotension; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizure; EPS, electrophysiological testing.

Consensus Statement 2—Competence and skills mix of physicians and staff required for syncope management in an SU

| Major and minor category . | 1. Diagnostic skills per syncope specialist . | 2. SU access to ancillary tests . | 3. SU ancillary tests . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syncope | |||

| Reflex | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, CSM, 24 h BP, ELR-ILR |

| Syncope due to OH | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, 24 h BP, autonomic testing |

| Cardiac syncope | Specialist knowledge | Full/preferential | ECG, telemetry, ELR-ILR, Echo, EPS |

| Epileptic seizures | |||

| General medical knowledge | Preferential | EEG, video-EEG monitoring, home video, neuroimaging | |

| Psychogenic T-LOC | |||

| PPS | General medical knowledge | Full/Preferential | TT, preferentially with video-EEG monitoring, home video |

| PNES | General medical knowledge | Preferential | video-EEG monitoring, home video |

| Major and minor category . | 1. Diagnostic skills per syncope specialist . | 2. SU access to ancillary tests . | 3. SU ancillary tests . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syncope | |||

| Reflex | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, CSM, 24 h BP, ELR-ILR |

| Syncope due to OH | Specialist knowledge | Full | TT, 24 h BP, autonomic testing |

| Cardiac syncope | Specialist knowledge | Full/preferential | ECG, telemetry, ELR-ILR, Echo, EPS |

| Epileptic seizures | |||

| General medical knowledge | Preferential | EEG, video-EEG monitoring, home video, neuroimaging | |

| Psychogenic T-LOC | |||

| PPS | General medical knowledge | Full/Preferential | TT, preferentially with video-EEG monitoring, home video |

| PNES | General medical knowledge | Preferential | video-EEG monitoring, home video |

TT, tilt table test; CSM, carotid sinus massage; ILR, implantable loop recorder; ELR, external loop recorder; BP, blood pressure; Echo, echocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; OH, orthostatic hypotension; PPS, psychogenic pseudosyncope; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizure; EPS, electrophysiological testing.

| Legend |

| The levels described here concern the SU as a whole, not those of individual physicians, except for column 1: the requested level of minimum basic diagnostic skills applies to each syncope specialist. |