-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sara Wallström, Lilas Ali, Inger Ekman, Karl Swedberg, Andreas Fors, Effects of a person-centred telephone support on fatigue in people with chronic heart failure: Subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, Volume 19, Issue 5, 1 June 2020, Pages 393–400, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515119891599

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Fatigue is a prevalent symptom that is associated with various conditions. In patients with chronic heart failure (CHF), fatigue is one of the most commonly reported and distressing symptoms and it is associated with disease progression. Person-centred care (PCC) is a fruitful approach to increase the patient’s ability to handle their illness.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of PCC in the form of structured telephone support on self-reported fatigue in patients with CHF.

This study reports a subgroup analysis of a secondary outcome measure from the Care4Ourselves randomised intervention. Patients (n=77) that were at least 50 years old who had been hospitalized due to worsening CHF received either usual care (n=38) or usual care and PCC in the form of structured telephone support (n=39). Participants in the intervention group created a health plan in partnership with a registered nurse. The plan was followed up and evaluated by telephone. Self-reported fatigue was assessed using the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20 (MFI-20) at baseline and at 6 months. Linear regression was used to analyse the change in MFI-20 score between the groups.

The intervention group improved significantly from baseline to the 6-month follow-up compared with the control group regarding the ‘reduced motivation’ dimension of the MFI-20 (Δ -1.41 versus 0.38, p=0.046).

PCC in the form of structured telephone support shows promise in supporting patients with CHF in their rehabilitation, improve health-related quality of life and reduce adverse events.

ISRCTN.com ISRCTN55562827

Introduction

Fatigue is a symptom of various conditions, such as rheumatology, cancer and heart disease.1 It is ‘a subjective, unpleasant symptom which incorporates total body feelings ranging from tiredness to exhaustion creating an unrelenting overall condition which interferes with individuals’ ability to function to their normal capacity’.2 Fatigue is by nature subjective, which means that it can only be assessed by the affected and cannot be observed by another person.2 Being affected by a symptom such as fatigue can greatly affect wellbeing and the ability to live life as wanted.3 It is therefore important that fatigue is acknowledged and managed in clinical practice.3

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a leading cause of death worldwide and is associated with frequent re-admissions and debilitating symptoms.4,5 Among patients with CHF, fatigue is one of the most common, prevalent and distressing symptoms that is associated with disease progression.6-8 This alone makes fatigue and other symptoms an important aspect to address in the care of patients with CHF, but self-reported fatigue is also connected with an increased risk of adverse events including death and hospital re-admission.9 Previous studies have shown that self-reported symptoms more accurately predict re-admission and mortality than symptoms assessed by healthcare professionals.10,11 The mechanisms behind fatigue in CHF are poorly understood, but are likely multifactorial.12 Self-care ability is affected by fatigue, which may partly explain why fatigue is associated with poor prognosis in CHF.13 Patients’ own beliefs about their illness influence their health behaviours and outcomes; therefore, supporting patients in increasing their perception of personal control is a possible strategy in rehabilitation aiming at decreasing fatigue and increasing health-related quality of life (HRQoL).14 Numerous previous studies have shown the importance of self-reported fatigue on HRQoL and that increased fatigue predicts adverse events in patients with CHF.7,9 There is a need for new methods for adequate clinical management of fatigue in patients with CHF.9

Previous studies have shown that traditional telephone support, which is focused on monitoring signs, can be effective in reducing re-admissions and mortality in patients with CHF.15 However, in contrast to the current international drive towards patient participation, patients are often regarded as passive recipients of care rather than active partners in their healthcare planning and in decisions regarding their own care.16

Person-centred care (PCC) relies on ethical principles that emphasize the importance of knowing the patient as a person with resources and needs. The starting point is carefully listening to the illness narrative, which may contain information on symptoms, how daily life is affected by the illness and care planning. The narrative is important for the professional to help identify resources and capabilities for the patient to manage the illness. A health plan, including identified personal capabilities, individual goals, medical tests and assessments, is formulated in partnership between the patient and the healthcare professional. The health plan and agreement are documented in the patient record so all parties have access to them.17,18

PCC has been shown to improve healthcare in several controlled trials in different conditions, settings and contexts. Regarding care of people with CHF, PCC reduces the length of stay in hospital,19 reduces uncertainty about the disease and treatment,20 improves the efficiency of the discharge process,21 lowers healthcare costs,22,23 reduces re-hospitalization rates and improves HRQoL,24 optimizes pharmacological treatment25 and slows deteroration.26 There is, however, a lack of studies investigating whether PCC in the form of structured telephone support effects self-reported fatigue in people with CHF.16

Aim

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of PCC in the form of structured telephone support on self-reported fatigue in patients with CHF.

Method

Study design

This study reports a subgroup analysis of a secondary outcome measure from the Care4Ourselves intervention. This comprised a randomised controlled trial evaluating the effects of PCC in the form of structured telephone support added to usual care versus usual care alone on patient-reported and clinical outcomes in patients with CHF and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The study methods and procedure of the Care4Ourselves intervention have been presented in detail elsewhere but are briefly described in the following.26

Population and setting

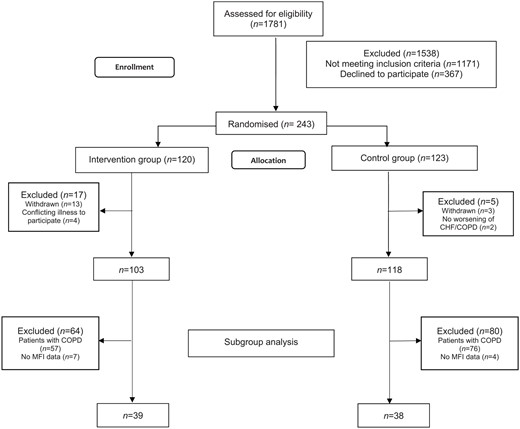

Patients admitted at one hospital site at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden were screened consecutively and enrolled between January 2015 and November 2016. For the main study,26 inclusion criteria were: at least 50 years old, ownership of a telephone as well as a current subscription to a telephone provider and currently hospitalized owing to worsening CHF and/or COPD. The exclusion criteria were: severe hearing and/or cognitive impairment, ongoing alcohol and/or drug abuse, no registered address within the region, survival expectancy of less than one year and participating in a conflicting study. For this substudy, only patients with a diagnosis of CHF who had answered at least one dimension of the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20 (MFI-20) questionnaire at baseline were included (Figure 1).

Eligible patients were asked to participate during their hospital stay when their condition had stabilised sufficiently. All patients received oral information and gave written consent to participate. Randomisation, to either the intervention or control group, was based on a computer-generated list, which stratified for age (⩽74 or ⩾75) and diagnosis (CHF, COPD or CHF and COPD).

Control group

Participants in the control group received usual care in accordance with current treatment guidelines.5 Usual care focuses on medical treatment and often includes visits to cardiologists, registered nurses (RNs) and physiotherapists at specialist heart failure clinics. When the patients are assessed as medically stable, they may also be referred to primary care for additional follow-up.

Intervention group

Participants in the intervention group received, in addition to usual care, PCC in the form of structured telephone support. The intervention lasted for 6 months from the initial call. Date and time for the first call was agreed upon while the participants were still in hospital. The time of the first call was 1–4 weeks after discharge from hospital, depending on what had been agreed upon during the hospitalisation. The PCC intervention was conducted by four RNs.

During the telephone interaction, the RNs strived to create a partnership with the patients.18,26 The starting point was to listen to the patients’ narratives and ask questions to identify their resources and potential for self-care. The RNs explored the participants’ wishes, abilities and problem areas, for example how to manage and reduce symptom burden. The patients and the RNs jointly formulated reachable goals, which were evaluated during the 6-month study period. A brief summary of the conversation and the agreed goals were documented in a health plan that was sent via mail to the patients. During the telephone interactions, the RNs strived to support the patients in achieving their goals and manage those areas the patients found problematic, for example living with symptoms and handling everyday issues. There were no restrictions on the number of calls and the number varied. Plans for additional calls were made in agreement between the RNs and patients. Details about how and when the patient and the RN would have further contact during the remaining study period were also included in the plan. If necessary, the health plan was reviewed and revised in follow-up conversations between the patient and the RN. In addition to the agreed-upon conversations, the patients could contact the RNs during office hours.26

In preparation for the study, the RNs received extensive face-to-face training in person-centred communication. These educational sessions were aimed at developing the RNs’ person-centred communication skills (such as listening, asking open-ended questions and giving reflections), documentation skills and their understanding of the philosophical underpinnings of PCC. Moreover, the sessions included working on translating the knowledge into skills used in PCC in the form of telephone support. During the intervention period (from inclusion start to 6 months after last participant was included), the RNs had educational sessions every other week with a group of specialists in PCC, communication and pedagogics. To further deepen the RNs’ knowledge about PCC, ascertain the application of PCC into practice in accordance with the study protocol26 and check for internal validation, the RNs and the group of specialists reviewed some of the RNs recorded calls and documentation of the health plans including the participants’ goals, wishes, abilities and problem areas.

Collection of data and sources

Self-reported fatigue was assessed with MFI-20, which is a 20-item questionnaire covering five dimensions of fatigue. It gives information about both the degree of fatigue and a multidimensional meaning of it, which makes it possible to identify a fatigue profile for each person. The questionnaire is short and easy to administrate and gives information on the intensity and characteristics of the fatigue. The MFI-20 provides a total summary score representing a global fatigue and scores on five underlying dimensions of fatigue: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced motivation, reduced activity and mental fatigue.27 Each of the five dimensions comprises four statements that are answered on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Yes, that is true’ to ‘No, that is not true’. Both positive and negative statements are included. The possible score in each dimension is 4–20 points, where a higher score indicates more fatigue. The timeframe measured is fatigue experienced in the last few days.28 The questionnaire is used extensively and has been validated in Sweden in both patients with cardiac conditions29 and cancer30 and found to be valid, reliable and usable in different contexts. When tested, Cronbach’s α values of the different dimensions of the MFI-20 ranged from 0.67 to 0.94.30

The MFI-20 questionnaire was distributed to the participants during their hospital stay (baseline) and a follow-up questionnaire along with a return envelope was mailed to all participants 6 months after hospital discharge. Patients whose questionnaires were not returned within 2 weeks were reminded at least twice by telephone and replacement questionnaires were sent if needed. Data about previous diseases, baseline medical background and care were retrieved from the participants’ medical records.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to compare baseline characteristics between the groups. Categorical variables were analysed using Pearson’s chi squared and Fischer’s exact tests and expressed as frequencies and means or percentages. Continued variables were compared using Student’s t-test and expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs). Linear regression was used to analyse change in MFI-20 score between the groups. The model was adjusted for baseline differences in body mass index between the groups and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. When calculating scores in the MFI-20 dimensions, the half-scale principle was applied for randomly missing items.

Standardised response means (SRMs) were analysed to estimate magnitudes of between-group changes in MFI-20 scores. The SRM was calculated as the differences between the mean change scores divided by the pooled SD change in both groups. SRM magnitudes were interpreted in accordance with the criteria set by Cohen: trivial (0 to <0.2), small (0.2 to 0.5), moderate (0.5 to 0.8) and large (⩾0.8). Small SRMs correspond to the minimum clinically important differences.31 All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of p⩽0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Ethics and reporting guidelines

All patients received verbal information about the study and gave their signed informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (DNo. 687-14) and conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.32 The study conforms to the CONSORT guidelines for non-pharmacological treatment.33

Results

In total, 77 patients with CHF were included in this study: 38 in the usual care group and 39 in the intervention group. The average age of the participants was 80.1 (SD = 9.67) years old. Most were men and living alone. The only statistical difference between the groups regarding baseline characteristics was that the control group had a higher average body mass index (p=0.044). There were no statistical differences between the groups concerning medical history or medication treatment (Table 1).

| . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 78.6 (8.6) | 81.6 (10.5) | 0.166 |

| Women (%) | 13 (34.2) | 15 (38.5) | 0.814 |

| BMI (SD) | 28.5 (5.7) | 25.9 (5.2) | 0.044 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SD) | 128.3 (18.9) | 124.7 (18.6) | 0.413 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (SD) | 73.4 (10.2) | 76.9 (12.1) | 0.180 |

| Heart rate (SD) | 78.7 (23.5) | 80.6 (16.2) | 0.683 |

| Civil status | 0.494 | ||

| Married/ living with partner (%) | 18 (47.4) | 15 (38.5) | |

| Living alone (%) | 20 (52.6) | 24 (61.5) | |

| Smoking | 0.192 | ||

| Never smoked (%) | 18 (48.6) | 21 (53.8) | |

| Current smoker (%) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Previous smoker (%) | 16 (43.2) | 18 (46.2) | |

| Medical history | |||

| Previous MI (%) | 11 (28.9) | 11 (28.2) | 1.000 |

| Previous angina (%) | 10 (26.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0.272 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 23 (60.5) | 30 (76.9) | 0.145 |

| Hypertension (%) | 25 (65.8) | 22 (56.4) | 0.485 |

| Diabetes (%) | 14 (36.8) | 9 (23.1) | 0.220 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 3 (7.9) | 5 (12.8) | 0.711 |

| CABG (%) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| CRT (%)* | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 0.115 |

| Pacemaker (%) | 9 (23.7) | 5 (12.8) | 0.250 |

| Medication treatment | |||

| ACE inhibitor (%)** | 21 (28.0) | 15 (20.0) | 0.251 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker (%)* | 13 (35.1) | 13 (33.3) | 1.000 |

| Oral β-blockers (%) | 36 (94.7) | 33 (84.6) | 0.263 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%)** | 10 (27.0) | 6 (15.8) | 0.271 |

| . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 78.6 (8.6) | 81.6 (10.5) | 0.166 |

| Women (%) | 13 (34.2) | 15 (38.5) | 0.814 |

| BMI (SD) | 28.5 (5.7) | 25.9 (5.2) | 0.044 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SD) | 128.3 (18.9) | 124.7 (18.6) | 0.413 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (SD) | 73.4 (10.2) | 76.9 (12.1) | 0.180 |

| Heart rate (SD) | 78.7 (23.5) | 80.6 (16.2) | 0.683 |

| Civil status | 0.494 | ||

| Married/ living with partner (%) | 18 (47.4) | 15 (38.5) | |

| Living alone (%) | 20 (52.6) | 24 (61.5) | |

| Smoking | 0.192 | ||

| Never smoked (%) | 18 (48.6) | 21 (53.8) | |

| Current smoker (%) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Previous smoker (%) | 16 (43.2) | 18 (46.2) | |

| Medical history | |||

| Previous MI (%) | 11 (28.9) | 11 (28.2) | 1.000 |

| Previous angina (%) | 10 (26.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0.272 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 23 (60.5) | 30 (76.9) | 0.145 |

| Hypertension (%) | 25 (65.8) | 22 (56.4) | 0.485 |

| Diabetes (%) | 14 (36.8) | 9 (23.1) | 0.220 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 3 (7.9) | 5 (12.8) | 0.711 |

| CABG (%) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| CRT (%)* | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 0.115 |

| Pacemaker (%) | 9 (23.7) | 5 (12.8) | 0.250 |

| Medication treatment | |||

| ACE inhibitor (%)** | 21 (28.0) | 15 (20.0) | 0.251 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker (%)* | 13 (35.1) | 13 (33.3) | 1.000 |

| Oral β-blockers (%) | 36 (94.7) | 33 (84.6) | 0.263 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%)** | 10 (27.0) | 6 (15.8) | 0.271 |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CHF: chronic heart failure; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy, MI: myocardial infarction; PCC: person-centred care; SD: standard deviation.

One missing.

Two missing.

| . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 78.6 (8.6) | 81.6 (10.5) | 0.166 |

| Women (%) | 13 (34.2) | 15 (38.5) | 0.814 |

| BMI (SD) | 28.5 (5.7) | 25.9 (5.2) | 0.044 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SD) | 128.3 (18.9) | 124.7 (18.6) | 0.413 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (SD) | 73.4 (10.2) | 76.9 (12.1) | 0.180 |

| Heart rate (SD) | 78.7 (23.5) | 80.6 (16.2) | 0.683 |

| Civil status | 0.494 | ||

| Married/ living with partner (%) | 18 (47.4) | 15 (38.5) | |

| Living alone (%) | 20 (52.6) | 24 (61.5) | |

| Smoking | 0.192 | ||

| Never smoked (%) | 18 (48.6) | 21 (53.8) | |

| Current smoker (%) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Previous smoker (%) | 16 (43.2) | 18 (46.2) | |

| Medical history | |||

| Previous MI (%) | 11 (28.9) | 11 (28.2) | 1.000 |

| Previous angina (%) | 10 (26.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0.272 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 23 (60.5) | 30 (76.9) | 0.145 |

| Hypertension (%) | 25 (65.8) | 22 (56.4) | 0.485 |

| Diabetes (%) | 14 (36.8) | 9 (23.1) | 0.220 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 3 (7.9) | 5 (12.8) | 0.711 |

| CABG (%) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| CRT (%)* | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 0.115 |

| Pacemaker (%) | 9 (23.7) | 5 (12.8) | 0.250 |

| Medication treatment | |||

| ACE inhibitor (%)** | 21 (28.0) | 15 (20.0) | 0.251 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker (%)* | 13 (35.1) | 13 (33.3) | 1.000 |

| Oral β-blockers (%) | 36 (94.7) | 33 (84.6) | 0.263 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%)** | 10 (27.0) | 6 (15.8) | 0.271 |

| . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | p-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 78.6 (8.6) | 81.6 (10.5) | 0.166 |

| Women (%) | 13 (34.2) | 15 (38.5) | 0.814 |

| BMI (SD) | 28.5 (5.7) | 25.9 (5.2) | 0.044 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SD) | 128.3 (18.9) | 124.7 (18.6) | 0.413 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (SD) | 73.4 (10.2) | 76.9 (12.1) | 0.180 |

| Heart rate (SD) | 78.7 (23.5) | 80.6 (16.2) | 0.683 |

| Civil status | 0.494 | ||

| Married/ living with partner (%) | 18 (47.4) | 15 (38.5) | |

| Living alone (%) | 20 (52.6) | 24 (61.5) | |

| Smoking | 0.192 | ||

| Never smoked (%) | 18 (48.6) | 21 (53.8) | |

| Current smoker (%) | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Previous smoker (%) | 16 (43.2) | 18 (46.2) | |

| Medical history | |||

| Previous MI (%) | 11 (28.9) | 11 (28.2) | 1.000 |

| Previous angina (%) | 10 (26.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0.272 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 23 (60.5) | 30 (76.9) | 0.145 |

| Hypertension (%) | 25 (65.8) | 22 (56.4) | 0.485 |

| Diabetes (%) | 14 (36.8) | 9 (23.1) | 0.220 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 3 (7.9) | 5 (12.8) | 0.711 |

| CABG (%) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| CRT (%)* | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 0.115 |

| Pacemaker (%) | 9 (23.7) | 5 (12.8) | 0.250 |

| Medication treatment | |||

| ACE inhibitor (%)** | 21 (28.0) | 15 (20.0) | 0.251 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker (%)* | 13 (35.1) | 13 (33.3) | 1.000 |

| Oral β-blockers (%) | 36 (94.7) | 33 (84.6) | 0.263 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%)** | 10 (27.0) | 6 (15.8) | 0.271 |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CHF: chronic heart failure; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy, MI: myocardial infarction; PCC: person-centred care; SD: standard deviation.

One missing.

Two missing.

In total, 129 calls (median 3.0, range 0–10) were conducted during the intervention. Of those, 118 calls were initiated by the RNs and 11 by the patients. On average, the RNs talked to the patients for 79.67 (median 61.0, range 0–378) minutes. During the 6-month study period, 12 (30.8%) patients in the PCC intervention group and 9 (23.7%) in the control group were re-admitted to hospital owing to worsening CHF (p=0.610).

The analysis shows that the intervention group improved significantly from baseline to the 6-month follow-up compared with the control group regarding the ‘reduced motivation’ dimension of the MFI-20. Differences between the groups appeared in adjusted (p=0.046) and unadjusted analyses (p=0.045; Table 2). The effect size using SRMs for the reduced motivation domain was moderate (SRM = 0.60; 95% CI 0.01–1.18%), and thus above the limit for the minimal clinically important difference. The difference between the change in the PCC and control groups in this dimension was 1.79 with a potential range of 4–20. No significant between-group differences were observed in the global MFI dimension or in the other four separate dimensions.

Comparison of the difference between groups (Δ baseline → 6 months) in the dimensions and global MFI-20

| Symptoma . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | 95% CIs . | Unadjusted p-value . | 95% CIs . | Adjusted p-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Lower . | Upper . | Lower . | Upper . | ||

| Global fatigue, mean (SD) | 68.2 (14.6)b | −0.92 (12.6)e | 63.6 (13.5)b | −5.57 (13.8)g | −12.395 | 3.095 | 0.233 | −11.435 | 4.257 | 0.362 |

| General fatigue, mean (SD) | 14.9 (3.9) | 0.22 (3.7)d | 14.6 (3.7) | −1.73 (3.2)f | −3.960 | 0.061 | 0.057 | −3.694 | 0.372 | 0.107 |

| Physical fatigue, mean (SD) | 15.9 (3.5)b | −1.15 (3.7)e | 14.7 (3.4)b | −0.70 (3.4)g | −1.665 | 2.576 | 0.667 | −1.266 | 2.959 | 0.424 |

| Reduced motivation, mean (SD) | 11.3 (3.8)b | 0.38 (2.7)e | 10.3 (3.5)b | −1.41 (3.3)g | −3.553 | −0.042 | 0.045 | −3.656 | −0.030 | 0.046 |

| Reduced activity, mean (SD) | 15.2(3.8)b | 0.06 (3.4)e | 14.2 (3.9)b | −1.71 (4.4)f | −4.009 | 0.462 | 0.117 | −3.984 | 0.626 | 0.149 |

| Mental fatigue, mean (SD) | 10.9 (4.1)c | −0.44 (3.5)e | 10.0 (3.3)b | −0.48 (3.8)g | −2.205 | 2.132 | 0.973 | −2.021 | 2.379 | 0.871 |

| Symptoma . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | 95% CIs . | Unadjusted p-value . | 95% CIs . | Adjusted p-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Lower . | Upper . | Lower . | Upper . | ||

| Global fatigue, mean (SD) | 68.2 (14.6)b | −0.92 (12.6)e | 63.6 (13.5)b | −5.57 (13.8)g | −12.395 | 3.095 | 0.233 | −11.435 | 4.257 | 0.362 |

| General fatigue, mean (SD) | 14.9 (3.9) | 0.22 (3.7)d | 14.6 (3.7) | −1.73 (3.2)f | −3.960 | 0.061 | 0.057 | −3.694 | 0.372 | 0.107 |

| Physical fatigue, mean (SD) | 15.9 (3.5)b | −1.15 (3.7)e | 14.7 (3.4)b | −0.70 (3.4)g | −1.665 | 2.576 | 0.667 | −1.266 | 2.959 | 0.424 |

| Reduced motivation, mean (SD) | 11.3 (3.8)b | 0.38 (2.7)e | 10.3 (3.5)b | −1.41 (3.3)g | −3.553 | −0.042 | 0.045 | −3.656 | −0.030 | 0.046 |

| Reduced activity, mean (SD) | 15.2(3.8)b | 0.06 (3.4)e | 14.2 (3.9)b | −1.71 (4.4)f | −4.009 | 0.462 | 0.117 | −3.984 | 0.626 | 0.149 |

| Mental fatigue, mean (SD) | 10.9 (4.1)c | −0.44 (3.5)e | 10.0 (3.3)b | −0.48 (3.8)g | −2.205 | 2.132 | 0.973 | −2.021 | 2.379 | 0.871 |

CI, confidence interval; PCC: person-centred care; SD: standard deviation.

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20.

1 missing.

2 missing.

11 missing.

12 missing.

17 missing.

18 missing.

Comparison of the difference between groups (Δ baseline → 6 months) in the dimensions and global MFI-20

| Symptoma . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | 95% CIs . | Unadjusted p-value . | 95% CIs . | Adjusted p-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Lower . | Upper . | Lower . | Upper . | ||

| Global fatigue, mean (SD) | 68.2 (14.6)b | −0.92 (12.6)e | 63.6 (13.5)b | −5.57 (13.8)g | −12.395 | 3.095 | 0.233 | −11.435 | 4.257 | 0.362 |

| General fatigue, mean (SD) | 14.9 (3.9) | 0.22 (3.7)d | 14.6 (3.7) | −1.73 (3.2)f | −3.960 | 0.061 | 0.057 | −3.694 | 0.372 | 0.107 |

| Physical fatigue, mean (SD) | 15.9 (3.5)b | −1.15 (3.7)e | 14.7 (3.4)b | −0.70 (3.4)g | −1.665 | 2.576 | 0.667 | −1.266 | 2.959 | 0.424 |

| Reduced motivation, mean (SD) | 11.3 (3.8)b | 0.38 (2.7)e | 10.3 (3.5)b | −1.41 (3.3)g | −3.553 | −0.042 | 0.045 | −3.656 | −0.030 | 0.046 |

| Reduced activity, mean (SD) | 15.2(3.8)b | 0.06 (3.4)e | 14.2 (3.9)b | −1.71 (4.4)f | −4.009 | 0.462 | 0.117 | −3.984 | 0.626 | 0.149 |

| Mental fatigue, mean (SD) | 10.9 (4.1)c | −0.44 (3.5)e | 10.0 (3.3)b | −0.48 (3.8)g | −2.205 | 2.132 | 0.973 | −2.021 | 2.379 | 0.871 |

| Symptoma . | Control group n=38 . | PCC group n=39 . | 95% CIs . | Unadjusted p-value . | 95% CIs . | Adjusted p-value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Baseline . | Δ baseline 6 months . | Lower . | Upper . | Lower . | Upper . | ||

| Global fatigue, mean (SD) | 68.2 (14.6)b | −0.92 (12.6)e | 63.6 (13.5)b | −5.57 (13.8)g | −12.395 | 3.095 | 0.233 | −11.435 | 4.257 | 0.362 |

| General fatigue, mean (SD) | 14.9 (3.9) | 0.22 (3.7)d | 14.6 (3.7) | −1.73 (3.2)f | −3.960 | 0.061 | 0.057 | −3.694 | 0.372 | 0.107 |

| Physical fatigue, mean (SD) | 15.9 (3.5)b | −1.15 (3.7)e | 14.7 (3.4)b | −0.70 (3.4)g | −1.665 | 2.576 | 0.667 | −1.266 | 2.959 | 0.424 |

| Reduced motivation, mean (SD) | 11.3 (3.8)b | 0.38 (2.7)e | 10.3 (3.5)b | −1.41 (3.3)g | −3.553 | −0.042 | 0.045 | −3.656 | −0.030 | 0.046 |

| Reduced activity, mean (SD) | 15.2(3.8)b | 0.06 (3.4)e | 14.2 (3.9)b | −1.71 (4.4)f | −4.009 | 0.462 | 0.117 | −3.984 | 0.626 | 0.149 |

| Mental fatigue, mean (SD) | 10.9 (4.1)c | −0.44 (3.5)e | 10.0 (3.3)b | −0.48 (3.8)g | −2.205 | 2.132 | 0.973 | −2.021 | 2.379 | 0.871 |

CI, confidence interval; PCC: person-centred care; SD: standard deviation.

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20.

1 missing.

2 missing.

11 missing.

12 missing.

17 missing.

18 missing.

There were some missing data at the 6-month follow-up as 11–13 (29–34%) participants in the control group and 17–18 (44–48%) in the intervention group had missing data in one or more of the dimensions. Out of these, 16 participants (eight in each group) died before the 6-month follow-up (Table 2).

Discussion

The present study evaluated the effects of PCC in the form of structured telephone support on self-reported fatigue in patients with CHF. The results indicate that PCC in the form of structured telephone support shows promise to reduce self-reported fatigue in patients with CHF. More specifically, the ‘reduced motivation’ dimension of the MFI-20 was significantly improved in the PCC group compared with the usual care group. Although the PCC group reported higher motivation compared with the control group at baseline, and therefore should have had less chance of improving, a significant improvement was seen in the PCC group compared with the control group. In addition, the baseline score of reduced motivation in the PCC group was comparable with those of patients of a similar age with CHF in previous research.8 The effect size was moderate, which is above the minimum clinically important difference. Thus, these results may have important implications for recovery in patients with worsening CHF.

The ‘reduced motivation’ dimension includes the following statements: I feel like doing all sorts of nice things; I dread having to do things; I have a lot of plans; and I don’t feel like doing anything.27 These items are quite congruent to the content in PCC, encouraging using one’s own capabilities such as will and motivation in planning for health. We have shown in a previous study evaluating PCC that elderly patients with CHF retained their daily life capacity while shortening hospital stay.19 Participants in both groups in the present study reported more fatigue in all dimensions of the MFI-20 than what is reported by general populations of a similar age.34 The average age in the present study was 80.1 and at the 6-month follow-up, the average scores for reduced motivation were 11.7 and 9.0 for the control and intervention groups, respectively. Variance in self-reported motivation among patients with CHF has been explained in a previous study by age and that patients report diminishing motivation with increased age.35 This study, which used MFI-20, showed that the mean scores in the reduced motivation dimension (range 4–20) were 7.8 (⩽64 years), 9.3 (65–79 years) and 12.0 (⩾80 years).35 This indicates that the results from our study regarding PCC in the form of structured telephone support show promise, improving the motivation to make plans and perform tasks equivalent to being 10 years younger.

That only reduced motivation was improved by the PCC intervention could be related to the nature of different types of fatigue. Previous research showed that the other dimensions of the MFI-20 are correlated to anaemia in patients with CHF,35 which indicates a substantial biomedical component that may not be optimally addressed through telephone intervention. In addition, reduced motivation was not associated with function class, sense of coherence, uncertainty in illness, gender, educational level or marital status.6,35 Reduced motivation, however, is dependent on depression rather than biomedical markers; therefore, person-centred telephone support may be a suitable intervention for patients with this aspect of fatigue.8

One explanation of why PCC in the form of structured telephone support is suitable in improving motivation may be the focus in PCC on abilities and resources rather than problems.17,18 Motivation in itself is an ability and it seems to be nourished within PCC when the patients are encouraged to formulate their personal goals supported by the RN. Achieving goals is encouraging, which reinforces motivation to pursue further goals. Moreover, the personal symptom experience is an important part of the illness narrative because it forms the foundation for the health plan that is co-created between the patient and the healthcare professional. When the focus shifts from measurable signs to self-reported experiences, the power dynamic of the relationship changes.18,36 The patients oversee the direction of their health plan and are supported by healthcare professionals. This approach empowers the patients to become more confident as they can take care of their own health.26

Another reason why PCC as structured telephone support shows potential could be the focus of the intervention. While most forms of structured telephone support interventions for people with CHF living in the community improve HRQoL, reduce all-cause mortality and heart failure-related hospitalization, structured telephone support focusing on clinical support, such as how to manage and reduce symptom burden, as in the present intervention, rather than patient education has shown greater benefits.15 PCC as structured telephone support, therefore, has great potential not only to improve HRQoL for people living with CHF but also to reduce the risk of adverse events.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, it is a sub study to the Care4Ourselves intervention,26 so randomisation was not based on this group. Second, the result is based on a secondary outcome measure for which no power calculations were performed. Third, the study sample was relatively small, which may lead to underestimation of the differences. Fourth, New York Heart Association class and left-ventricle ejection fraction were not consistently documented in the medical record and could therefore not be controlled for. Fifth, other potentially confounding variables than those detailed in the patient characteristics could not be controlled for, these may therefore have affected the findings. Sixth, there were differences in baseline characteristics between the groups. Finally, the proportion of missing data at follow-up was rather high. However, the measured data are self-reported by the participants, which minimizes bias and increases the likelihood that the results closely reflect the actual experience of the participants.

Conclusion

PCC in the form of structured telephone support shows promise to reduce self-reported fatigue in patients with CHF. This approach, which tailors to patients’ needs and preferences, shows potential to support patients in their rehabilitation and may improve HRQoL and reduce the risk of adverse events.

Fatigue is a prevalent and distressing symptom in chronic heart failure.

Symptom management is a key aspect of nursing.

Person-centred care as telephone support improved fatigue.

Person-centred care via telephone is a strategy for supporting patients with chronic heart failure.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Centre for Person-Centred Care at the University of Gothenburg (GPCC), Sweden. GPCC is funded by the Swedish Government’s grant for Strategic Research Areas, Care Sciences (Application to Swedish Research Council no. 2009-1088) (IE) and co-funded by the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. The Swedish Research Council (DNr 521-2013-2723) (IE), the Swedish agreement between the government and the county councils concerning economic support for providing an infrastructure for research and education of doctors (ALFGBG-444681) (IE), and Research and Development Unit, Primary Health Care, Region Västra Götaland also contributed to the funding of the study (AF). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

Comments