-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Christos Kourek, Robert Greif, Georgios Georgiopoulos, Maaret Castrén, Bernd Böttiger, Nicolas Mongardon, Jochen Hinkelbein, Francesc Carmona-Jiménez, Andrea Scapigliati, Michal Marchel, György Bárczy, Marc Van de Velde, Juraj Koutun, Elena Corrada, Gert Jan Scheffer, Dimitrios Dougenis, Theodoros Xanthos, Healthcare professionals’ knowledge on cardiopulmonary resuscitation correlated with return of spontaneous circulation rates after in-hospital cardiac arrests: A multicentric study between university hospitals in 12 European countries, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, Volume 19, Issue 5, 1 June 2020, Pages 401–410, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515119900075

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In-hospital cardiac arrest is a major cause of death in European countries, and survival of patients remains low ranging from 20% to 25%.

The purpose of this study was to assess healthcare professionals’ knowledge on cardiopulmonary resuscitation among university hospitals in 12 European countries and correlate it with the return of spontaneous circulation rates of their patients after in-hospital cardiac arrest.

A total of 570 healthcare professionals from cardiology, anaesthesiology and intensive care medicine departments of European university hospitals in Italy, Poland, Hungary, Belgium, Spain, Slovakia, Germany, Finland, The Netherlands, Switzerland, France and Greece completed a questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 12 questions based on epidemiology data and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and 26 multiple choice questions on cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge. Hospitals in Switzerland scored highest on basic life support (P=0.005) while Belgium hospitals scored highest on advanced life support (P<0.001) and total score in cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge (P=0.01). The Swiss hospitals scored highest in cardiopulmonary resuscitation training (P<0.001). Correlation between cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge and return of spontaneous circulation rates of patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest demonstrated that each additional correct answer on the advanced life support score results in a further increase in return of spontaneous circulation rates (odds ratio 3.94; 95% confidence interval 2.78 to 5.57; P<0.001).

Differences in knowledge about resuscitation and course attendance were found between university hospitals in 12 European countries. Education in cardiopulmonary resuscitation is considered to be vital for patients’ return of spontaneous circulation rates after in-hospital cardiac arrest. A higher level of knowledge in advanced life support results in higher return of spontaneous circulation rates.

Introduction

In-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) is a major cause of death within European countries, and causes a tremendous burden on their healthcare systems and resources.1 In developed countries, the prevalence of IHCA has been estimated as 1–5/1000 hospital admissions.2 National campaigns designed to reduce in-hospital deaths after cardiac arrests, the development of emergency response teams and improvements in post-cardiac care have led to a slight increase of survival of patients after IHCA over the past decade.3,4 However, survival rates still remain low ranging from 20% to 25% for adults, usually with a dismal prognosis.5,6

Education in resuscitation is crucial for the survival of a patient with an IHCA, the neurological outcome and the quality of the patient’s life.7 It has been shown that patients experiencing cardiac arrest in hospitals with a higher percentage of healthcare professionals well trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) courses present with lower mortality.8

The primary aim of this observational multicentre study was to evaluate the CPR knowledge of healthcare professionals from cardiology and anaesthesiology departments and intensive care units (ICUs) among university hospitals in 12 European countries, and to correlate the scores of the CPR knowledge with the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) rates of their patients after IHCA. As a secondary aim, we sought to classify healthcare professionals according to their department, their specialty and the attendance of CPR courses and compare CPR knowledge scores among different groups.

Methods

Study design

This observational, cross-sectional multicentre study investigated healthcare professionals’ CPR knowledge. Study participants provided informed consent and subsequently filled in a questionnaire which was created by the research group. Ethical approval was first obtained from the local ethics committee (approval no. B-201, ethics commission of Aretaieio Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Faculty of Medicine, Greece; Chairperson Professor Ioannis Vasileiou) and then locally from each university hospital in Europe. The investigation conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Questionnaire development

The questionnaire was translated into each country’s official language by the translation service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Athens (Greece) and then checked twice by a native doctor from each country who was also proficient in English. It was divided into two main parts. The first part included 12 participants’ epidemiology questions (gender, age, specialty, department, professional experience and training in CPR). The term ‘CPR course attendance’ referred to any type of attended CPR course approved by the American Heart Association (AHA) or the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) including basic life support (BLS), immediate life support (ILS), advanced life support (ALS), advanced cardiac life support (ACLS), European paediatric basic life support course (EPBLS), European paediatric immediate life support (EPILS), European paediatric advanced life support (EPALS), newborn life support (NLS), European trauma course (ETC) and advanced trauma life support (ATLS). The total score in CPR course attendance was arbitrarily defined as the number of different types of attended CPR courses per participant after graduation. The second part was the assessment of their theoretical knowledge and it was based on the 2015 ERC CPR guidelines.9,10 It included 10 multiple choice questions (MCQs) in BLS, three MCQs in ischaemic stroke and 13 MCQs in ALS. The total score in CPR knowledge was defined as the sum of BLS, ischaemic stroke and ALS MCQs (26 MCQs). BLS questions assessed healthcare professionals’ knowledge on the algorithm of the resuscitation process while ALS questions assessed healthcare professionals’ knowledge on the ECG rhythms, the reversible causes of cardiac arrest, the defibrillator and the drugs during the process.

Reliability and validity analysis of the questionnaire

A pilot questionnaire was distributed to 10 BLS and five ALS instructors of a training centre in Athens, Greece. All questions on which consensus could not be reached were removed. The pilot questionnaire was also assessed by three CPR experts from the University of Athens. After the pilot stage, the questionnaire was distributed to 100 healthcare professionals from European university hospitals, trying to collect an equal sample of 8 to 10 questionnaires from each country. The test–retest procedure was used for the assessment of its reliability. One hundred healthcare professionals were asked to complete the same questionnaire under the same conditions 1 month later. The results were transferred to a new database and after a cross-checking we examined the correlation of their scores.

The questionnaire’s reliability analysis was based on: (a) Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) and (b) the intraclass correlation coefficient of absolute agreement in estimated measurements by two-way random-effects models. Two measurements of ALS, BLS and total score in CPR knowledge within the same set of subjects were analysed. Spearman correlation coefficients for repeated measurements by questionnaires were rho=0.523 (P<0.001) for BLS, rho=0.659 (P<0.001) for ALS, rho=0.900 (P<0.001) for a total score in CPR knowledge and rho=0.998 (P<0.001) for a total score in CPR course attendance.

The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated for BLS (odds ratio (OR), 0.670; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.509 to 0.788; P<0.001), ALS (OR 0.788; 95% CI 0.685 to 0.857; P<0.001), ischaemic stroke (OR 0.416; 95% CI 0.132 to 0.607; P=0.004), total score in CPR knowledge (OR 0.948; 95% CI 0.923 to 0.965; P<0.001) and total score in CPR course attendance (OR 0.996; 95% CI 0.994 to 0.997; P<0.001). According to Cicchetti et al.,11 correlation was good for BLS, moderate for ischaemic stroke and perfect for ALS total score in CPR knowledge and total score in CPR course attendance (see Supplementary Table 1).

Bland–Altman analysis did not reveal evidence of systemic bias for the two measurements of ALS and total score in CPR knowledge in different time points by the same questionnaire. Bland–Altman plots for ALS and total score in CPR knowledge are shown in Supplementary Figure 1(a and b).

Data collection

Epidemiological data such as the number of patients with an IHCA of the previous month and their ROSC rates were gathered and provided retrospectively by the directors of the departments of the university hospitals that participated in the study (Table 1). All these updated epidemiological data were gathered according to each hospital’s official registries and concerned only the previous month before the survey was conducted. These numbers do not correspond to the mean ROSC of these departments within a year.

Average number of patients with IHCA per month and ROSC rates from participating university hospitals per country

| Country . | Average number of patients with IHCA per month (N) . | ROSC rates (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | 84 | 60 |

| Poland | 50 | 25 |

| Hungary | 36 | 50 |

| Belgium | 24 | 85 |

| Spain | 100 | 40 |

| Slovakia | 79 | 20 |

| Germany | 72 | 35 |

| Finland | 60 | 60 |

| The Netherlands | 45 | 50 |

| Switzerland | 50 | 35 |

| France | 120 | 40 |

| Greece | 80 | 30 |

| Country . | Average number of patients with IHCA per month (N) . | ROSC rates (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | 84 | 60 |

| Poland | 50 | 25 |

| Hungary | 36 | 50 |

| Belgium | 24 | 85 |

| Spain | 100 | 40 |

| Slovakia | 79 | 20 |

| Germany | 72 | 35 |

| Finland | 60 | 60 |

| The Netherlands | 45 | 50 |

| Switzerland | 50 | 35 |

| France | 120 | 40 |

| Greece | 80 | 30 |

IHCA: in-hospital cardiac arrest; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation.

Average number of patients with IHCA per month and ROSC rates from participating university hospitals per country

| Country . | Average number of patients with IHCA per month (N) . | ROSC rates (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | 84 | 60 |

| Poland | 50 | 25 |

| Hungary | 36 | 50 |

| Belgium | 24 | 85 |

| Spain | 100 | 40 |

| Slovakia | 79 | 20 |

| Germany | 72 | 35 |

| Finland | 60 | 60 |

| The Netherlands | 45 | 50 |

| Switzerland | 50 | 35 |

| France | 120 | 40 |

| Greece | 80 | 30 |

| Country . | Average number of patients with IHCA per month (N) . | ROSC rates (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | 84 | 60 |

| Poland | 50 | 25 |

| Hungary | 36 | 50 |

| Belgium | 24 | 85 |

| Spain | 100 | 40 |

| Slovakia | 79 | 20 |

| Germany | 72 | 35 |

| Finland | 60 | 60 |

| The Netherlands | 45 | 50 |

| Switzerland | 50 | 35 |

| France | 120 | 40 |

| Greece | 80 | 30 |

IHCA: in-hospital cardiac arrest; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation.

ROSC was defined as the documented return of adequate circulation in the absence of ongoing chest compressions for at least 20 consecutive minutes (return of adequate pulse/heart rate by palpation, auscultation, Doppler, arterial blood pressure waveform, or documented blood pressure >50 mmHg systolic) achieved during the event.12 Any ROSC was considered as a positive outcome and the initial ROSC following cardiopulmonary resuscitation after IHCA was demonstrated without any reference to the neurological outcome or hospital discharge. We decided to set ROSC as an endpoint because we wanted to focus on the immediate result of resuscitation. Survival is affected by a variety of independent variables (e.g. comorbidities of patients, ICU treatment, care in a cardiac arrest centre, etc). On the other hand, collecting survival data over time and hospital discharge information is far more difficult to obtain than to collect ROSC data. Furthermore, we gathered data in this study only from 1 month before the survey. Many patients with IHCA may have not been discharged yet and no long-term survival data were available. Directors of the departments who provided us with data on the number of patients with an IHCA and their ROSC rates were not aware of the mean scores or the identity of healthcare professionals who completed the questionnaires in order to avoid bias in our research.

Selection of hospitals and departments

The study was conducted from March 2016 to December 2017. Invitation for participation was sent from the main researcher on resuscitation (CK) to 28 countries of the European Union plus Switzerland. Twelve of them, including Italy, Poland, Hungary, Belgium, Spain, Slovakia, Germany, Finland, The Netherlands, Switzerland, France and Greece, accepted to participate in the study within this time period. Invitation was also sent to all university hospitals of these countries. Sixteen university hospitals that responded within the first week of the invitation were included in the study. However, the names of the university hospitals in every country are being kept confidential for reasons of anonymity.

Healthcare professionals, both physicians and nurses from departments which are most directly connected with IHCA such as cardiology departments (including coronary care units), anaesthesiology departments and ICUs were urged to participate in the survey. Healthcare professionals from emergency departments (EDs) were excluded from the protocol due to the high number of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Our primary aim is to study patients with IHCA and their ROSC rates. EDs usually present a high degree of readiness and as a result the ROSC rates of their patients with OHCA may be higher than the average rates of the hospital.

Study conduction

Questionnaires regarding CPR knowledge were distributed to the participants with a statement describing the purpose of the study and ethical aspects such as anonymity and voluntary participation. Participants were motivated to participate in the survey by the chief of their department in each university hospital. Their participation was voluntary and depended on their clinical duties and their working shifts. Each healthcare professional was given 20 minutes to answer the questionnaire anonymously under the supervision of either the main researcher of the project or a cooperator and return it back. Small groups of five healthcare professionals usually completed the questionnaire before their working shift, during their breaks or after the end of their clinical duties. Each completed questionnaire was enclosed in an envelope by the participant who filled it in and it was opened only by the main researcher (CK) after the end of the study.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed variables. Respectively, nominal variables are presented as absolute and percentage values (%). Normal distribution of all continuous variables was graphically inspected through appropriate graphs (i.e. quantile–quantile plots). Parameters that deviated from normality assumption were log transformed in regression models.

Differences in BLS, ALS, total score in CPR knowledge and total score in CPR course attendance among countries, departments, specialties and CPR course attendance were initially assessed with the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. Pairwise comparisons with reference category were also performed and the level of observed statistical significance was adjusted to 0.05/number of comparison to account for multiple comparisons. Subsequently, we used multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis to compare further the parameters of interest after controlling for confounders (including age, gender, specialty, education, professional experience and department status). The selection of confounders was driven by the previous literature and biological plausibility. In detail, we adjusted for body weight as it is considered a major factor in delivering proper chest compression along with age and gender.13 The likelihood of CPR training varies in groups with different age, educational status or income.14 We also used CPR course attendance, professional experience, department and specialty as indicators of education and experience in CPR or possible confounders (i.e. different volume of cardiac arrests according to the department).

Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA package, version 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). We deemed statistical significance to be P=0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 2. More detailed descriptive characteristics are outlined in Supplementary Table 2.

| Variable . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 570 (100%) |

| Gender | |

| Men | 218 (38.2%) |

| Women | 352 (61.8%) |

| Age (in years) | |

| 18–24 | 45 (7.9%) |

| 25–34 | 257 (45.1%) |

| 35–44 | 141 (24.8%) |

| 45–54 | 76 (13.3%) |

| 55+ | 51 (8.9%) |

| Specialty | |

| Specialised physicians | 220 (38.6%) |

| Residents | 99 (17.4%) |

| Nurses | 232 (40.7%) |

| Non-resident physicians | 19 (3.3%) |

| Department | |

| Cardiology | 166 (29.1%) |

| Anaesthesiology | 221 (38.8%) |

| Intensive care units | 178 (31.2%) |

| Other departments | 5 (0.9%) |

| Professional experience (⩽5 years) | 223 (39.1%) |

| Attendance of at least one type of any CPR coursea (Yes) | 423 (79.8%) |

| BLS course attendancea (Yes) | 295 (55.7%) |

| ALS course attendancea (Yes) | 229 (43.2%) |

| Other CPR course attendancea (No) | 487 (91.9%) |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea (1 point) | 214 (40.4%) |

| Time from the last CPR course attendanceb (1–5 years) | 218 (51.5%) |

| Evaluation of CPR coursesb (Very good) | 194 (45.9%) |

| Willingness to attend a CPR course in the futurea (Yes) | 492 (92.8%) |

| Personal experience in a cardiac arrest incident | |

| No | 50 (8.8%) |

| Active participation | 492 (86.3%) |

| Passive participation (only watch) | 28 (4.9%) |

| Variable . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 570 (100%) |

| Gender | |

| Men | 218 (38.2%) |

| Women | 352 (61.8%) |

| Age (in years) | |

| 18–24 | 45 (7.9%) |

| 25–34 | 257 (45.1%) |

| 35–44 | 141 (24.8%) |

| 45–54 | 76 (13.3%) |

| 55+ | 51 (8.9%) |

| Specialty | |

| Specialised physicians | 220 (38.6%) |

| Residents | 99 (17.4%) |

| Nurses | 232 (40.7%) |

| Non-resident physicians | 19 (3.3%) |

| Department | |

| Cardiology | 166 (29.1%) |

| Anaesthesiology | 221 (38.8%) |

| Intensive care units | 178 (31.2%) |

| Other departments | 5 (0.9%) |

| Professional experience (⩽5 years) | 223 (39.1%) |

| Attendance of at least one type of any CPR coursea (Yes) | 423 (79.8%) |

| BLS course attendancea (Yes) | 295 (55.7%) |

| ALS course attendancea (Yes) | 229 (43.2%) |

| Other CPR course attendancea (No) | 487 (91.9%) |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea (1 point) | 214 (40.4%) |

| Time from the last CPR course attendanceb (1–5 years) | 218 (51.5%) |

| Evaluation of CPR coursesb (Very good) | 194 (45.9%) |

| Willingness to attend a CPR course in the futurea (Yes) | 492 (92.8%) |

| Personal experience in a cardiac arrest incident | |

| No | 50 (8.8%) |

| Active participation | 492 (86.3%) |

| Passive participation (only watch) | 28 (4.9%) |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Τotal number of eligible subjects did not include France due to lack of education data (n=530).

Τotal number of eligible subjects was derived from healthcare professionals who had participated in a CPR course (n=423).

| Variable . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 570 (100%) |

| Gender | |

| Men | 218 (38.2%) |

| Women | 352 (61.8%) |

| Age (in years) | |

| 18–24 | 45 (7.9%) |

| 25–34 | 257 (45.1%) |

| 35–44 | 141 (24.8%) |

| 45–54 | 76 (13.3%) |

| 55+ | 51 (8.9%) |

| Specialty | |

| Specialised physicians | 220 (38.6%) |

| Residents | 99 (17.4%) |

| Nurses | 232 (40.7%) |

| Non-resident physicians | 19 (3.3%) |

| Department | |

| Cardiology | 166 (29.1%) |

| Anaesthesiology | 221 (38.8%) |

| Intensive care units | 178 (31.2%) |

| Other departments | 5 (0.9%) |

| Professional experience (⩽5 years) | 223 (39.1%) |

| Attendance of at least one type of any CPR coursea (Yes) | 423 (79.8%) |

| BLS course attendancea (Yes) | 295 (55.7%) |

| ALS course attendancea (Yes) | 229 (43.2%) |

| Other CPR course attendancea (No) | 487 (91.9%) |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea (1 point) | 214 (40.4%) |

| Time from the last CPR course attendanceb (1–5 years) | 218 (51.5%) |

| Evaluation of CPR coursesb (Very good) | 194 (45.9%) |

| Willingness to attend a CPR course in the futurea (Yes) | 492 (92.8%) |

| Personal experience in a cardiac arrest incident | |

| No | 50 (8.8%) |

| Active participation | 492 (86.3%) |

| Passive participation (only watch) | 28 (4.9%) |

| Variable . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 570 (100%) |

| Gender | |

| Men | 218 (38.2%) |

| Women | 352 (61.8%) |

| Age (in years) | |

| 18–24 | 45 (7.9%) |

| 25–34 | 257 (45.1%) |

| 35–44 | 141 (24.8%) |

| 45–54 | 76 (13.3%) |

| 55+ | 51 (8.9%) |

| Specialty | |

| Specialised physicians | 220 (38.6%) |

| Residents | 99 (17.4%) |

| Nurses | 232 (40.7%) |

| Non-resident physicians | 19 (3.3%) |

| Department | |

| Cardiology | 166 (29.1%) |

| Anaesthesiology | 221 (38.8%) |

| Intensive care units | 178 (31.2%) |

| Other departments | 5 (0.9%) |

| Professional experience (⩽5 years) | 223 (39.1%) |

| Attendance of at least one type of any CPR coursea (Yes) | 423 (79.8%) |

| BLS course attendancea (Yes) | 295 (55.7%) |

| ALS course attendancea (Yes) | 229 (43.2%) |

| Other CPR course attendancea (No) | 487 (91.9%) |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea (1 point) | 214 (40.4%) |

| Time from the last CPR course attendanceb (1–5 years) | 218 (51.5%) |

| Evaluation of CPR coursesb (Very good) | 194 (45.9%) |

| Willingness to attend a CPR course in the futurea (Yes) | 492 (92.8%) |

| Personal experience in a cardiac arrest incident | |

| No | 50 (8.8%) |

| Active participation | 492 (86.3%) |

| Passive participation (only watch) | 28 (4.9%) |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Τotal number of eligible subjects did not include France due to lack of education data (n=530).

Τotal number of eligible subjects was derived from healthcare professionals who had participated in a CPR course (n=423).

Differences in CPR knowledge and CPR course attendance among countries

MCQ performance in the written test and the results in BLS, ALS, total score in CPR knowledge and total score in CPR course attendance for participating hospitals in different countries are outlined in Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 2. Hospitals in Switzerland scored the highest on BLS with eight correct answers out of 10 questions (7 to 8, P=0.005) while Belgian hospitals scored the highest on ALS with 10 correct answers out of 13 questions (9 to 11, P<0.001) and total score in CPR knowledge with 19 correct answers out of 26 questions (17 to 21, P=0.011). The Swiss hospitals scored the highest in CPR course attendance with two (1 to 3, P<0.001) different kinds of CPR courses per participant.

Number of participants, BLS, ALS, total score in knowledge and total score in CPR course attendance per country

| Country . | No. of participants (n) . | Scores . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . | CPR course attendance . |

| Italy | 75 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 18 (15 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Poland | 50 | 7 (6 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10)a | 18 (16 to 19) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Hungary | 45 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10)a | 17 (14 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Belgium | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 10 (9 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) | 1.5 (1 to 2) |

| Spain | 80 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (16 to 19)a | 1 (1 to 2) |

| Slovakia | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 11) | 17.5 (14.5 to 21) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| Germany | 40 | 8 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10.5) | 18.5 (15.5 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Finland | 40 | 7 (7 to 9) | 10 (8 to 10) | 19 (15.5 to 20) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| The Netherlands | 40 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10) | 18 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Switzerland | 40 | 8 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 19 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 3) |

| France | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 7 (5 to 9)a | 16 (14 to 18)a | NA |

| Greece | 40 | 6 (6 to 7.5)a | 9 (6 to 10)a | 17 (13 to 18)a | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.005 | P<0.001 | P=0.01 | P<0.001 | |

| Country . | No. of participants (n) . | Scores . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . | CPR course attendance . |

| Italy | 75 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 18 (15 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Poland | 50 | 7 (6 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10)a | 18 (16 to 19) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Hungary | 45 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10)a | 17 (14 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Belgium | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 10 (9 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) | 1.5 (1 to 2) |

| Spain | 80 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (16 to 19)a | 1 (1 to 2) |

| Slovakia | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 11) | 17.5 (14.5 to 21) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| Germany | 40 | 8 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10.5) | 18.5 (15.5 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Finland | 40 | 7 (7 to 9) | 10 (8 to 10) | 19 (15.5 to 20) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| The Netherlands | 40 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10) | 18 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Switzerland | 40 | 8 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 19 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 3) |

| France | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 7 (5 to 9)a | 16 (14 to 18)a | NA |

| Greece | 40 | 6 (6 to 7.5)a | 9 (6 to 10)a | 17 (13 to 18)a | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.005 | P<0.001 | P=0.01 | P<0.001 | |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Switzerland was set as the reference country for BLS and total score in education and Belgium was set as the reference country for ALS and total score in knowledge.

Significant pairwise difference in parameter of interest to the reference country.

NA (not available) due to lack of education data in France.

Number of participants, BLS, ALS, total score in knowledge and total score in CPR course attendance per country

| Country . | No. of participants (n) . | Scores . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . | CPR course attendance . |

| Italy | 75 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 18 (15 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Poland | 50 | 7 (6 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10)a | 18 (16 to 19) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Hungary | 45 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10)a | 17 (14 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Belgium | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 10 (9 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) | 1.5 (1 to 2) |

| Spain | 80 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (16 to 19)a | 1 (1 to 2) |

| Slovakia | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 11) | 17.5 (14.5 to 21) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| Germany | 40 | 8 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10.5) | 18.5 (15.5 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Finland | 40 | 7 (7 to 9) | 10 (8 to 10) | 19 (15.5 to 20) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| The Netherlands | 40 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10) | 18 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Switzerland | 40 | 8 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 19 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 3) |

| France | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 7 (5 to 9)a | 16 (14 to 18)a | NA |

| Greece | 40 | 6 (6 to 7.5)a | 9 (6 to 10)a | 17 (13 to 18)a | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.005 | P<0.001 | P=0.01 | P<0.001 | |

| Country . | No. of participants (n) . | Scores . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . | CPR course attendance . |

| Italy | 75 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 18 (15 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Poland | 50 | 7 (6 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10)a | 18 (16 to 19) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Hungary | 45 | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10)a | 17 (14 to 20) | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Belgium | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 10 (9 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) | 1.5 (1 to 2) |

| Spain | 80 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (16 to 19)a | 1 (1 to 2) |

| Slovakia | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 11) | 17.5 (14.5 to 21) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| Germany | 40 | 8 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10.5) | 18.5 (15.5 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Finland | 40 | 7 (7 to 9) | 10 (8 to 10) | 19 (15.5 to 20) | 0 (0 to 1)a |

| The Netherlands | 40 | 7 (7 to 8) | 9 (8 to 10) | 18 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 2) |

| Switzerland | 40 | 8 (7 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 19 (16 to 20) | 2 (1 to 3) |

| France | 40 | 7 (6 to 8) | 7 (5 to 9)a | 16 (14 to 18)a | NA |

| Greece | 40 | 6 (6 to 7.5)a | 9 (6 to 10)a | 17 (13 to 18)a | 1 (1 to 2)a |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.005 | P<0.001 | P=0.01 | P<0.001 | |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Switzerland was set as the reference country for BLS and total score in education and Belgium was set as the reference country for ALS and total score in knowledge.

Significant pairwise difference in parameter of interest to the reference country.

NA (not available) due to lack of education data in France.

By multivariable logistic regression analysis, hospitals in Belgium were associated with higher ALS score than hospitals in Poland, Hungary, Spain, Germany, The Netherlands, Switzerland and Greece and a higher total score in CPR knowledge than hospitals in Spain, Germany, The Netherlands and Greece after taking into account between-countries differences in age,13 gender,13 CPR course attendance,14 professional experience and department and specialty distribution (see Supplementary Table 3).

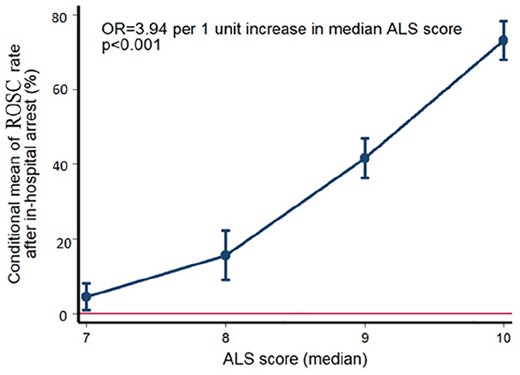

Correlation between scores in CPR knowledge and ROSC rates of patients after IHCA

Among indices of CPR knowledge, the ALS score was independently associated with increased ROSC rates after IHCA (Table 4). In particular, for each additional correct answer in the ALS score, patients presented 3.94-fold increase (95% CI 2.78 to 5.57; P<0.001) in odds for ROSC after IHCA after taking into account age, gender, specialty (rates of doctors and nurses), previous attendance of a CPR course, experience and mixture of participating departments (Figure 1). BLS, total score in CPR knowledge and total score in CPR course attendance were not related to ROSC rates (P>0.05).

BLS, ALS, total score in CPR knowledge per specialty, department and CPR course attendance

| Variable . | Scores . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . |

| Specialty | |||

| Specialised physicians | 8 (7 to 8) | 10 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Residents | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Nurses | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (6 to 9) | 16 (14 to 18) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| Department | |||

| Cardiology | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Anaesthesiology | 7 (6.5 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10) | 19 (16 to 20)a |

| Intensive care units | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17.5 (15 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.002 | P=0.331 | P=0.034 |

| CPR course attendanceb | |||

| Yes | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 18 (16 to 20) |

| No | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.249 | P=0.002 | P=0.038 |

| Variable . | Scores . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . |

| Specialty | |||

| Specialised physicians | 8 (7 to 8) | 10 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Residents | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Nurses | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (6 to 9) | 16 (14 to 18) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| Department | |||

| Cardiology | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Anaesthesiology | 7 (6.5 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10) | 19 (16 to 20)a |

| Intensive care units | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17.5 (15 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.002 | P=0.331 | P=0.034 |

| CPR course attendanceb | |||

| Yes | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 18 (16 to 20) |

| No | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.249 | P=0.002 | P=0.038 |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Cardiology was set as reference department for BLS, ALS and total score in knowledge.

Significant pairwise difference in parameter of interest to the reference department.

Any type of attended CPR course approved by the European Resuscitation Council.

BLS, ALS, total score in CPR knowledge per specialty, department and CPR course attendance

| Variable . | Scores . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . |

| Specialty | |||

| Specialised physicians | 8 (7 to 8) | 10 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Residents | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Nurses | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (6 to 9) | 16 (14 to 18) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| Department | |||

| Cardiology | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Anaesthesiology | 7 (6.5 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10) | 19 (16 to 20)a |

| Intensive care units | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17.5 (15 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.002 | P=0.331 | P=0.034 |

| CPR course attendanceb | |||

| Yes | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 18 (16 to 20) |

| No | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.249 | P=0.002 | P=0.038 |

| Variable . | Scores . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | BLS (max 10) . | ALS (max 13) . | CPR knowledge (max 26) . |

| Specialty | |||

| Specialised physicians | 8 (7 to 8) | 10 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Residents | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 19 (17 to 21) |

| Nurses | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (6 to 9) | 16 (14 to 18) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| Department | |||

| Cardiology | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Anaesthesiology | 7 (6.5 to 8)a | 9 (7 to 10) | 19 (16 to 20)a |

| Intensive care units | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (7 to 10) | 17.5 (15 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.002 | P=0.331 | P=0.034 |

| CPR course attendanceb | |||

| Yes | 7 (6 to 8) | 9 (8 to 11) | 18 (16 to 20) |

| No | 7 (6 to 8) | 8 (7 to 10) | 17 (14 to 20) |

| Observed significance (P value) | P=0.249 | P=0.002 | P=0.038 |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Cardiology was set as reference department for BLS, ALS and total score in knowledge.

Significant pairwise difference in parameter of interest to the reference department.

Any type of attended CPR course approved by the European Resuscitation Council.

Increase in odds for return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) rates after in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) according to median advance life support (ALS) score among university hospitals in 12 European countries. Mean ROSC rate is depicted on the Y20 axis conditional to the ALS score, after adjustment for age, gender, specialty (rates of doctors and nurses), previous attendance of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) course, experience and mixture of participating departments by fractional regression analysis

Differences in CPR knowledge between specialties, departments and CPR course attendance

Performance in the written test and the results in BLS, ALS and total score in CPR knowledge between specialties, departments and CPR course attendance are demonstrated in Table 5. Specialised physicians scored the highest on BLS with 8 correct answers out of 10 questions (7 to 8, P<0.001) and ALS with 10 correct answers out of 13 questions (8 to 11, P<0.001). However, they had the same total score in CPR knowledge with residents with 19 correct answers out of 26 questions (17 to 21, P<0.001).

| Part of the questionnaire . | OR (95%CI) . | Level of significance (P value) . |

|---|---|---|

| BLS | 0.25 (0.07 to 1.87) | 0.29 |

| ALS | 3.94 (2.78 to 5.57) | <0.001 |

| Total score in CPR knowledge | 2.4 (0.8 to 7.19) | 0.12 |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea | 0.08 (0.001 to 24.38) | 0.39 |

| Part of the questionnaire . | OR (95%CI) . | Level of significance (P value) . |

|---|---|---|

| BLS | 0.25 (0.07 to 1.87) | 0.29 |

| ALS | 3.94 (2.78 to 5.57) | <0.001 |

| Total score in CPR knowledge | 2.4 (0.8 to 7.19) | 0.12 |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea | 0.08 (0.001 to 24.38) | 0.39 |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CI: confidence interval; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IHCA: in-hospital cardiac arrest; OR: odds ratio; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation.

Lack of educational data for France.

| Part of the questionnaire . | OR (95%CI) . | Level of significance (P value) . |

|---|---|---|

| BLS | 0.25 (0.07 to 1.87) | 0.29 |

| ALS | 3.94 (2.78 to 5.57) | <0.001 |

| Total score in CPR knowledge | 2.4 (0.8 to 7.19) | 0.12 |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea | 0.08 (0.001 to 24.38) | 0.39 |

| Part of the questionnaire . | OR (95%CI) . | Level of significance (P value) . |

|---|---|---|

| BLS | 0.25 (0.07 to 1.87) | 0.29 |

| ALS | 3.94 (2.78 to 5.57) | <0.001 |

| Total score in CPR knowledge | 2.4 (0.8 to 7.19) | 0.12 |

| Total score in CPR course attendancea | 0.08 (0.001 to 24.38) | 0.39 |

ALS: advanced life support; BLS: basic life support; CI: confidence interval; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IHCA: in-hospital cardiac arrest; OR: odds ratio; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation.

Lack of educational data for France.

Healthcare professionals (both physicians and nurses) from anaesthesiology departments scored the highest in the total score in CPR knowledge with 19 correct answers out of 26 questions (16 to 20, P=0.034) while they had the same score in BLS and ALS with healthcare professionals from cardiology departments and ICUs.

Finally, healthcare professionals who had attended at least one CPR course scored higher in ALS with 9 correct answers out of 13 questions (8 to 11, P=0.002) and total score in CPR knowledge with 18 correct answers out of 26 questions (16 to 20, P=0.038) in comparison with those who had never attended a CPR course before.

By multivariable logistic regression analysis, anaesthesiology departments were associated with higher BLS, ALS and total score in CPR knowledge than cardiology departments after taking into account between-departments differences in age,13 gender,13 education status,14 professional experience and specialty distribution (see Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

This is an observational, cross-sectional multicentre questionnaire study of healthcare professionals’ knowledge in CPR. For the first time, there was evaluation and comparison of knowledge in CPR between university hospitals in 12 European countries. Our major outcome was the correlation between the results in ALS and the ROSC rates of patients with IHCA and the importance of CPR education. Higher knowledge in the field of resuscitation leads to improved patient ROSC rates and outcomes in different European countries with their differences in healthcare.

Hospitals in Switzerland seemed to have better performance in BLS and total score in CPR course attendance, while hospitals in Belgium demonstrated better results in ALS and total score in CPR knowledge. We observed that the high income countries in central and northern Europe perform better both in theoretical knowledge and CPR training. In contrast, as we approached the southern and less economically powerful countries, performance decreased. Each country’s available resources for its national health system may be an important factor. Despite the lack of solid data supporting a direct association between financial status and CPR performance, it is tempting to hypothesise that high income countries were associated with higher educational status as compared with low income countries. In this direction, accumulative evidence has shown that austerity measures during past years have led to a deterioration in the quality of health services,15–18 an increase in mortality19,20 and a lower level in education.21,22 Countries with reduced resources and large cuts in health expenditure such as Greece cannot keep pace with the rapid growth rates of countries such as Belgium and Switzerland. However, the study by Squires and Anderson23 showed that spending more on healthcare does not result in better outcomes or longer life expectancy of each country’s patients, possibly showing the loose correlation between ROSC rates and life expectancy. Considerable efforts are being made in order to enable healthcare professionals to respond to these difficult conditions. The initiatives of each healthcare professional and volunteering are crucial steps to achieve this goal.

Nurses and physicians are the first who respond to IHCA by applying standardised CPR.24 In this study, specialised physicians appeared to have higher scores in CPR knowledge than residents and nurses, in contrast with other studies in which there were no differences between specialties.25,26 These differences may occur due to the structure of the educational background of each specialty. Medical undergraduate education is longer and more complex than nurses’ undergraduate education. As a result, physicians gain more knowledge than any other healthcare professional. This fact is also supported by the study of Plagisou et al.,27 in which nurses with higher educational status scored better than nurses with lower educational background. In addition, specialised doctors have more experience than residents both in theoretical and practical parts. These could be the possible reasons that specialised physicians showed higher scores than the other subgroups.

As far as departments are concerned, we decided to study cardiology and anaesthesiology departments and ICUs. A survey in Poland showed that the accompanying mortality of patients with IHCA seems to be lower than average at ICUs, cardiology departments, coronary care units and emergency medicine departments in comparison with other departments.28 This conclusion reflects the fact that CPR education in these departments may be more effective. Anaesthesiology departments had a better score in the questionnaire than cardiology departments and ICUs. An explanation of these results may be due to the fact that anaesthesiologists and nurses in anaesthesiology departments are the main members of the resuscitation team in a case of IHCA in many European hospitals and as a result they perform resuscitation better.

We also emphasised the vital importance of CPR course attendance in relation to the knowledge and performance of healthcare professionals in CPR. Pettersen et al.29 found a positive association between participants’ performance on the practical cardiopulmonary resuscitation test and the frequency of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and whether cardiopulmonary resuscitation training was offered in the workplace. Kalhori et al.25 showed a correlation between CPR course attendance and the results of the questionnaire. More specifically, those who had attended at least one CPR course (either doctors or nurses) during their lifetime achieved better scores than those who had not attended any CPR courses. The same results were demonstrated by Pantazopoulos et al.,30 in which doctors who had attended an ACLS course outperformed doctors without ACLS course experience. Our study confirms that healthcare professionals who had attended at least one CPR course had higher scores in ALS and the total score of the questionnaire than those who had not. We compared healthcare participants who had attended any type of an approved CPR course (BLS, ILS, ALS, ACLS, EPBLS, EPILS, EPALS, NLS ETC, ATLS) and those who had not. We did not separate healthcare professionals according to which type of CPR course they had attended. In this way, we emphasise the importance of education in CPR, no matter the type of the course.

The most important finding of our study was the correlation of performance in CPR knowledge with ROSC rates of patients with IHCA. Several studies have demonstrated that hospitals with healthcare professionals with a higher education level and better cognitive background experience reduced mortality and the number of their patients’ complications.31–33 In addition, evidence suggests that implementation of the resuscitation guidelines leads to a positive benefit when considering survival to hospital discharge, ROSC and CPR performance.7,34 Irrespectively, the likelihood of benefit is high relative to possible harm.34 It has also been shown that patients in hospitals that have a greater percentage of healthcare professionals with more training in CPR courses experience lower mortality.8,35 Our study brings empirical evidence to the meta-analysis of Lockey et al.7 by showing that countries with a higher ALS score, which is the most important algorithm of treating an IHCA, had higher ROSC rates for their patients. These results also highlight the importance of training healthcare professionals in CPR on a regular basis within their hospitals and departments. Healthcare professionals who are well trained and familarised with the ALS algorithm have higher possibilities to save a victim after an IHCA. Moreover, differences between specialties and departments should guide specific CPR programmes for the different healthcare providers.

The study presented a large number of quantitative results which helped us to distinguish correlations or differences in the CPR knowledge among healthcare professionals in different European university hospitals. To date, no similar study has examined differences in CPR knowledge among such a large number of European countries, and previous research used to evaluate healthcare professionals of a specific specialty, department or hospital.25–27,30,36–39 However, it should be emphasised that the main purpose of our study was not a head-to-head comparison of health systems across Europe; instead, we sought to evince differences in CPR knowledge or training among European countries that may depend on the economic national status. In the context, a link between available financial resources for teaching and training and CPR efficiency in real life settings might be established. Our findings merit further confirmation from additional studies and, thus, should be critically interpreted.

This study has some important limitations. Although high significance for differences in CPR scores is shown between countries, the numbers and ranges seem very similar. Beyond observed statistical significance, focus should be placed on clinically meaningful differences in achieved scores among different countries, departments and professional status.40 Despite highly significant differences in ROSC rates and exposure variables (mean BLS, ALS score, total score in CPR knowledge and score in CPR course attendance), our findings should be interpreted with caution in light of the small effect sizes; this could be partially explained by the combination of multiple factors to determine the final outcome (successful or unsuccessful) in cardiac arrest patients. Still, our study provides for the first time numeric estimates for the contribution of CPR knowledge to this endpoint. The choice of healthcare professionals and university hospitals in each country was random and mostly based on their availability and their willingness to participate in the survey. Moreover, healthcare professionals from hospitals with different standards might result in different results and ROSC rates of patients with IHCA. The educational background of the participants was unknown, and homogeneity between specialties, departments and other epidemiological data in the sample could not be predicted in advance. Larger samples within each country and participation of more people in each group could increase the reliability of the results, and might reflect in a better way each country’s level of resuscitation. Although associations were identified between CPR knowledge and ROSC rate, we still need to understand better how the various emergency medical teams operate. Further epidemiological studies are needed to delineate this issue. Finally, other important parameters that have a direct effect on ROSC such as quality of CPR,41 response time, time to first shock and ALS medication were not investigated in order to say with certainty that performance in real time was totally in agreement with the quality of CPR knowledge.

In conclusion, differences in knowledge about resuscitation and course attendance were found between university hospitals in 12 European countries. There is a correlation between ALS knowledge and ROSC rates. Education in CPR is considered to be vital for patients’ ROSC rates after IHCA. Higher level of knowledge in ALS results in higher ROSC rates. The next step of our study as a consequence of our results would be to investigate whether effective training standards for CPR could result in high CPR knowledge, which could be linked with higher rates of ROSC.

Acknowledgement

The author(s) would like to thank all the colleagues from all over Europe that filled out the forms and helped them to gather the material. They would also like to thank Konstantinos Pateras for his contribution to the statistical analysis.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training results in higher cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge.

Higher knowledge in advanced life support results in higher return of spontaneous circulation rates.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation courses are important for physicians and nurses.

Author contribution

All author(s) have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. CK and RG joint first authors.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available online.

References

Comments