-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stephan Windecker, Alan G Fraser, Piotr Szymanski, Martine Gilard, Thomas F Lüscher, Leila Abid, John Brennan, Robert Byrne, Lia Crotti, Inga Drossart, Jennifer Franke, Mario Gabrielli Cossellu, Ajay J Kirtane, Jana Kurucova, Mitchell Krucoff, Gearóid McGauran, Patrick O Myers, Donal B O’Connor, Radosław Parma, Paul Piscoi, Archana Rao, Andrea Rappagliosi, Giulio Stefanini, Eigil Samset, Alphons Vincent, Ralph Stephan von Bardeleben, Franz Weidinger, Priorities for medical device regulatory approval: a report from the European Society of Cardiology Cardiovascular Round Table, European Heart Journal, Volume 46, Issue 16, 21 April 2025, Pages 1469–1479, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf069

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The European Union (EU) Medical Device Regulation increased regulatory scrutiny to improve the safety and performance of new medical devices. An equally important goal is providing timely access to innovative devices to benefit patient care. The European Society of Cardiology strongly advocates for the evolution of the Medical Device Regulation system to facilitate priority access for innovative devices for unmet needs and orphan cardiovascular (CV) medical devices in EU countries. Although device approval is currently executed by Notified Bodies in the EU, it will be advantageous in the mid-term to consider a single EU regulatory agency for devices. In the short term, steps can be taken to transform the current system into a more efficient, predictable, cost-effective, and user-friendly service. Key strategies include the following: enhancing predictability of the approval process through use of early scientific advice from regulators; establishing unique regulatory pathways for CV orphan, paediatric, and innovative devices; promoting more efficient (re)certification of essential legacy CV devices; improving transparency of sponsor interactions with Notified Bodies; expanding the roles of the Expert Panels to assist in the approval of CV devices; promoting global regulatory harmonization, considering streamlined authorization of CV medical technologies across selected jurisdictions; developing an efficient system to monitor device safety; and ensuring funding for data collection platforms. Some strategies that could help include considering a pilot programme for joint approval processes of selected devices in partnership with other regions (i.e. US Food and Drug Administration); developing priority pathways for accelerated access to innovative or orphan devices; and increasing recognition of the importance of early feasibility studies in the EU.

Potential strategies to help transform the current European medical device regulatory system into a more efficient, predictable, cost-effective, and user-friendly service

Introduction

Regulatory science and scrutiny are essential to advancing public health and in assessing the safety and performance of high-risk cardiovascular (CV) devices. Regulatory procedures must also facilitate timely access to innovative devices for the benefit of patient care. A central objective of the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) enacted in the European Union in 2017 [(EU) 2017/745] was to increase the quantity and improve the quality of clinical evidence to support the use of new high-risk medical devices. Following its introduction, concerns have arisen that research and clinical care in Europe, traditionally a global leader in CV medical device innovation, may be unintentionally altered.1–3 The lack of a central regulatory agency for medical devices, which has resulted in a decentralized approval system, may be one important problem. Creation of a single entity in analogy to drug approval in Europe has been suggested.4

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Cardiovascular Round Table (CRT) meetings provide a forum for regulators, industry sponsors (pharmaceutical, device, and diagnostic companies), clinicians, patients, and ESC Board Members to identify and discuss issues related to improving health in Europe. This paper summarises some key topics discussed at the second ESC CRT meeting on CV device innovation. A summary of the topics discussed at the first meeting in November 2022 has been published.1 Of note, these meetings do not develop official ESC policy. However, the Coordinating Research and Evidence for Medical Devices Consortium has been established to review and develop methods for the clinical evaluation of high-risk medical devices in Europe.5 The consortium, under ESC leadership, evaluated the evidence that was available before CV medical device market approval under the previous EU Medical Device Directive 93/42/EEC, and has made efforts to provide expert knowledge to the European Union (EU) regulators.6

This paper focuses on strategies to facilitate priority access into the European market for innovative CV devices that address unmet medical needs; promote progress in the global harmonization of regulatory systems; and support expedited access to orphan medical devices targeting rare diseases.

Innovative devices

Although the dictionary defines ‘innovation’ as ‘a new idea, method, or device’, true CV device innovation goes beyond mere newness. Definitions of innovative devices that may warrant priority regulatory review processes vary but generally include the criteria shown in Table 1.7–11

Summary of main criteria for priority regulatory review processes for devices in use in some countries

|

|

Based on references.7–11

Summary of main criteria for priority regulatory review processes for devices in use in some countries

|

|

Based on references.7–11

European investigators have played an essential role in developing innovative CV devices, performing numerous first-in-man interventions, and refining devices and their implantation techniques.1 These efforts promoted global communication of early experiences, and interaction with non-European regulatory agencies, and nurtured networks crucial for developing scientific standards for new device evaluation.12–14 The introduction of the MDR resulted in critical procedural uncertainties. The absence of dedicated, predictable pathways for regulating novel and orphan devices impacts the leadership role of Europe in device innovation and the quality of clinical care despite the availability of already approved lifesaving CV devices.

Need for evolution and legislative update of European regulatory device approval

The EU MDR was introduced in 2017 to establish ‘…a robust, transparent, predictable, and sustainable regulatory framework for medical devices which ensures a high level of safety and health whilst supporting innovation.’15 The necessity for improved evaluation of the safety and performance of CV devices was highlighted in a 2024 systematic review that demonstrated insufficient quantity and quality of published clinical evidence before regulatory approval (Ce-marking) of many devices.6

Device approval is currently executed by Notified Bodies in the EU. The European Commission defines Notified Bodies as ‘…an organization designated by an EU country to assess the conformity of certain products before being placed on the market. These bodies carry out tasks related to conformity assessment procedures set out in the applicable legislation, when a third party is required.’16 Numerous concerns have been voiced about the certification of new products since the introduction of the MDR. They include a lack of transparency of the process and clinical evidence;17 insufficient interaction between Notified Bodies and developers; uncertainty around Notified Body scientific expertise; no clear dedicated pathway(s) for approval of paediatric, orphan or innovative products; and a lack of EU common specifications for specific device types. Of note, Notified Bodies that assess medical devices have societal responsibilities for assessing the safety and performance of devices, but not of the medical procedures and patient pathways in which these devices are used.

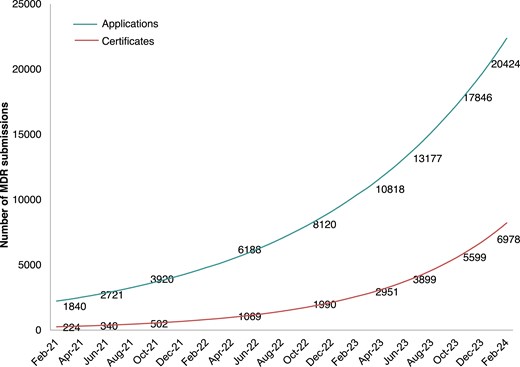

There continue to be issues with the timely implementation of the legislation. The initial transition period has been extended to December 2027 for high-risk devices and to December 2028 for medium- and lower-risk devices.18 Initial challenges included the limited capacity of Notified Bodies to handle applications quickly, but substantial progress has been made. As of May 2024, there were 61 Notified Bodies; 49 designated under the MDR and 12 under the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation (IVDR)19—up from 39 designated as of June 2023.20 The ongoing European Commission survey of Notified Bodies reported that 20 424 MDR applications had been filed for recertification, and 6978 certificates had been issued, as of the end of February 2024 (Figure 1).20 The number of certificates that have been filed doubled in one year, but the backlog remains substantial. In addition to the limited Notified Body capacity, the backlog may be related to the lack of special provisions for well-established, previously approved legacy devices, particularly those that raise no significant safety concerns. This raises a more general question about the need for, and usefulness of, recertification for all devices.

Numbers of applications received and certificates issued in Europe under the MDR, according to a survey of Notified Bodies (June 2023). From reference.20©European Union; MDR, Medical Device Regulation

High recertification costs have been highlighted by medical technology companies, especially for older or low-profit devices.3 This has led to the unavailability of some previously approved devices and shortages of well-established devices, which are particularly concerning for treating orphan diseases. Surveys report that about 17% of in vitro diagnostic devices (IVDs) and 20% of medical devices will be discontinued in Europe because the costs of transitioning to the new regulations outweigh revenue expectations, particularly among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).3 Furthermore, almost half of medical device manufacturers report that they are deprioritizing the EU market for first regulatory clearance of new devices, due to unpredictability, cost, and inefficiency, in favour of the well-structured FDA regulatory processes that facilitate access to the large US market.3

These issues related to the MDR suggest a need for evaluation and revision of the EU regulatory approval system. The MDR mandates that by May 2027, the European Commission must assess and report on the implementation of the Regulation and the progress towards achieving its objectives.15 The Medical Devices Unit of the Commission has recognized that there are problems, and the review is underway.

Priority access for innovative devices in the EU

Priority review pathways are needed to facilitate patient access to innovative devices in the EU. The goal of expedited pathways is to shorten the time from development to availability of treatments, primarily for life-threatening diseases and in areas of unmet medical needs. Promotion of greater use of certificates with conditions may be a facility to improve the efficiency of certification in such scenarios where appropriate.21

Substantial unmet needs can be identified by the Expert Panels or professional societies. Accelerated pathways typically include a predictable, defined process with strict eligibility criteria and ideally include early interactions between developers and regulators. Guidance on study methodology, expected outcomes, structured and transparent review, and recommendations for subsequent follow-up studies to gain market approval are particularly useful.6–10

Relevant precedents for these approaches to priority review pathways used around the world are shown in Table 2.22 In the United Kingdom, the Innovative Devices Access Pathway (IDAP), launched in September 2023, involves a team of experts to help device manufacturers develop a product-specific Target Development Profile roadmap. The roadmap includes a fast-tracked clinical review; scientific advice; discussions around commercial challenges and reimbursement options; and potentially exceptional use authorization (if safety standards are met).10

| Jurisdiction (Responsible body) . | Program/pathway name . | Details . |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (TGA) | Priority Review designation | Priority application guidelines and application forms are available |

| Canada (Health Canada) | Pathway for Advanced Therapeutic Products | Consultation period closed on March 2023. Innovation information meetings take place |

| China (NMPA) | Innovation Green Pathway | Applicant’s ownership of legal patent rights of the product's core technology in China |

| European Union (EU) | No priority programme for innovative devices | European Commission pilot of Expert Panels to support conformity assessment |

| Japan (PMDA) | Fast Track Review Process (Sakigake) | Fast-track review and conditional fast-track review pathways |

| United Kingdom (UK) (MHRA, NICE and other partners) | Innovative Devices Access Pathway (IDAP) | The pilot launched September 2023 |

| United States (US FDA) | Breakthrough Devices Program | Expedite pathways to speed development, assessment, and review of devices for life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions |

| Jurisdiction (Responsible body) . | Program/pathway name . | Details . |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (TGA) | Priority Review designation | Priority application guidelines and application forms are available |

| Canada (Health Canada) | Pathway for Advanced Therapeutic Products | Consultation period closed on March 2023. Innovation information meetings take place |

| China (NMPA) | Innovation Green Pathway | Applicant’s ownership of legal patent rights of the product's core technology in China |

| European Union (EU) | No priority programme for innovative devices | European Commission pilot of Expert Panels to support conformity assessment |

| Japan (PMDA) | Fast Track Review Process (Sakigake) | Fast-track review and conditional fast-track review pathways |

| United Kingdom (UK) (MHRA, NICE and other partners) | Innovative Devices Access Pathway (IDAP) | The pilot launched September 2023 |

| United States (US FDA) | Breakthrough Devices Program | Expedite pathways to speed development, assessment, and review of devices for life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions |

Adapted from reference.22

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; IDAP, Innovative Devices Access Pathway; MHRA, Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NMPA, National Medical Device Authority of PR China; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration.

| Jurisdiction (Responsible body) . | Program/pathway name . | Details . |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (TGA) | Priority Review designation | Priority application guidelines and application forms are available |

| Canada (Health Canada) | Pathway for Advanced Therapeutic Products | Consultation period closed on March 2023. Innovation information meetings take place |

| China (NMPA) | Innovation Green Pathway | Applicant’s ownership of legal patent rights of the product's core technology in China |

| European Union (EU) | No priority programme for innovative devices | European Commission pilot of Expert Panels to support conformity assessment |

| Japan (PMDA) | Fast Track Review Process (Sakigake) | Fast-track review and conditional fast-track review pathways |

| United Kingdom (UK) (MHRA, NICE and other partners) | Innovative Devices Access Pathway (IDAP) | The pilot launched September 2023 |

| United States (US FDA) | Breakthrough Devices Program | Expedite pathways to speed development, assessment, and review of devices for life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions |

| Jurisdiction (Responsible body) . | Program/pathway name . | Details . |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (TGA) | Priority Review designation | Priority application guidelines and application forms are available |

| Canada (Health Canada) | Pathway for Advanced Therapeutic Products | Consultation period closed on March 2023. Innovation information meetings take place |

| China (NMPA) | Innovation Green Pathway | Applicant’s ownership of legal patent rights of the product's core technology in China |

| European Union (EU) | No priority programme for innovative devices | European Commission pilot of Expert Panels to support conformity assessment |

| Japan (PMDA) | Fast Track Review Process (Sakigake) | Fast-track review and conditional fast-track review pathways |

| United Kingdom (UK) (MHRA, NICE and other partners) | Innovative Devices Access Pathway (IDAP) | The pilot launched September 2023 |

| United States (US FDA) | Breakthrough Devices Program | Expedite pathways to speed development, assessment, and review of devices for life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions |

Adapted from reference.22

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; IDAP, Innovative Devices Access Pathway; MHRA, Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NMPA, National Medical Device Authority of PR China; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration.

In the United States, the FDA offers programmes to facilitate access to innovative medical devices. The FDA’s Breakthrough Device Program launched in 2016, expedites the development, assessment, and review of devices that provide for a more effective treatment or diagnosis of life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions, especially those intended to address unmet clinical needs.9 In addition, in January 2023, the FDA launched the Total Product Life Cycle Advisory Program (TAP) Pilot to help spur more rapid development of innovative medical devices that are critical to public health.23 The TAP Pilot’s primary goal is to expedite patient access to devices by providing early, frequent, and strategic communications with the FDA and by facilitating engagement between developers and key non-FDA parties.

Currently, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) provides accelerated pathways for approval of medicinal products, such as the Priority Medicines (PRIME) programme introduced in 2016.7,8 During the first 5 years of the programme, the EMA received 384 PRIME requests, of which 95 were granted.8 Unfortunately, a similar pathway for devices is not yet available in the EU.

In March 2022, the EMA took over coordination of the medical device Expert Panels, and in January 2023 they launched a pilot scientific advice programme. The pilot prioritises medical devices that: (1) benefit a small number of patients (orphan/paediatric devices); (2) address an unmet medical need; and (3) have the potential to provide a major clinical impact.24 Programme updates in 2024 concluded that early advice was helpful to guide a clinical development plan, complemented by later advice to guide the post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) plan. Effective communication between Expert Panels and the manufacturers was considered vital to meet short timelines.25

The lack of a central regulatory agency for medical devices (similar to the EMA for drug approvals) results in a decentralized approval system that lacks adequate coordination. There are gaps in determining who would decide that devices meet the criteria for being ‘innovative’ and how they should be evaluated consistently. Manufacturers report concerns about an unpredictable roadmap, including a lack of early scientific advice, transparency regarding the information required for device certification, and approval timelines.3 Given a much shorter product lifecycle of many devices (compared with drugs) and the greater number of individual products and manufacturers in the device sector, compared to the drug sector, this can present a substantial burden. Although the Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) encourages Notified Bodies and manufacturers to have ‘structured dialogues’ before and throughout the review process, it is unclear to the manufacturers what can be discussed during these meetings, and they report a lack of responsiveness from Notified Bodies.3 Evaluation of the MDR, begun by the Commission in 2024, has highlighted the area of innovative or breakthrough devices, including the need to assess whether it is fit for purpose for fostering the availability of such devices in the EU.26

One suggested approach is the greater use of early feasibility studies (EFS) to speed the development of innovative devices and investigate initial safety and performance. In 2013, the FDA introduced an EFS programme in the United States. The programme has been well perceived by industry, contract research organizations, and clinical scientists, due to the responsiveness of FDA staff in direct interactions, which have enabled rapid protocol adaptations and resulted in a measurable shift to start clinical investigations earlier. In contrast, standards for EFS in the EU are not yet available.27

The HEU-EFS Project (Harmonized Approach to Early Feasibility Studies for Medical Devices in the EU) is a public–private partnership that aims to develop an EU harmonized framework to improve the uptake of EFS (www.heuefs.eu). Launched in January 2024, the project includes 22 consortium partners who will work over the next 4 years to assess the current status of pre-market evidence generation and develop and validate robust methodology for EFS in the EU.

In 2022, the IDEAL framework for device innovation was expanded to include preclinical development.28 The proposed recommendations suggest a pragmatic approach that minimizes the risk of first-in-human studies against the benefits of rapid access to new devices in clinical practice. They suggest that the need for evidence of safety and performance before progression to larger clinical studies increases with increasing invasiveness and risk of a device.

A representative from the ESC Patient Forum provided insights from patients who live with CV conditions. Patients feel there are pros and cons associated with accelerated pathways. They appreciate that they have the potential for faster access to devices that address unmet medical needs, for possible improvements in quality of life, and may encourage innovation. However, they recognise that there may be limited clinical evidence and experience with rapidly approved devices, and thus, a potential for harm and false hope if the device is unsuccessful.

Single governing body for medical devices in Europe

A key goal of the evolution of the EU regulatory system is to improve its efficiency, ensure the predictability of reviews, provide reliable guidance to manufacturers, and provide timely product access for patients. Efficient timelines are particularly important for devices. MedTech Europe, a European trade association representing 140 multinational corporations and 45 medical technology associations, supports the objectives of the MDR and the IVDR but has made suggestions to address some of the challenges that have arisen during their implementation.3 They propose a more efficient system that prioritises innovation and is managed under a single, dedicated governance structure (Table 3).3

Some of the suggested strategies proposed by the medical technology industry (MedTech Europe) to improve the current EU regulatory system

| Areas for improvement . | Strategies . |

|---|---|

| Efficiency System that is lean and adaptable |

|

| Innovation System to rapidly make innovative technologies addressing unmet needs available to patients |

|

| Governance A single governance structure to oversee the medical technology system |

|

| Areas for improvement . | Strategies . |

|---|---|

| Efficiency System that is lean and adaptable |

|

| Innovation System to rapidly make innovative technologies addressing unmet needs available to patients |

|

| Governance A single governance structure to oversee the medical technology system |

|

Based on reference.3

Some of the suggested strategies proposed by the medical technology industry (MedTech Europe) to improve the current EU regulatory system

| Areas for improvement . | Strategies . |

|---|---|

| Efficiency System that is lean and adaptable |

|

| Innovation System to rapidly make innovative technologies addressing unmet needs available to patients |

|

| Governance A single governance structure to oversee the medical technology system |

|

| Areas for improvement . | Strategies . |

|---|---|

| Efficiency System that is lean and adaptable |

|

| Innovation System to rapidly make innovative technologies addressing unmet needs available to patients |

|

| Governance A single governance structure to oversee the medical technology system |

|

Based on reference.3

There has long been a call for a single governing body for medical devices in the EU. As early as in 2011, an ESC policy conference called for ‘…a single, coordinated European system to oversee the evaluation and approval of medical devices.’4 Notably, this has been achieved in other countries; for example, the FDA in the United States and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan oversee both drugs and devices. Even within the current system of Notified Body approvals, substantial centralization could be considered. For example, greater use of National Agencies and the Expert Panels in the designation, assessment and certification (conformity assessment) of innovative, orphan or other high-risk CV devices could accelerate processes and improve predictability while maintaining high standards. Recently one of the political groups in the European Parliament proposed that revision of the MDR could achieve a degree of centralization of responsibilities and powers by establishing a ‘European Medical Devices Office’.29

Harmonizing global regulatory systems

International standards are a key step towards the harmonization of regulatory approval processes across countries and continents and potentially can lead to a system for mutual recognition across different jurisdictions.30 A shared focus on getting better, safer devices to patients faster will foster collaborative approaches to interpreting existing statutes and may promote joint approvals without necessitating new legislation or cumbersome political processes. Standardixed consensus definitions help to ensure data interpretability across jurisdictions and may allow for international generalizability of research data, as well as improved global surveillance of devices pre- and post-approval, particularly supporting early detection of safety signals.

For global device manufacturers, regulatory harmonization facilitates planning of research and development across international markets. More efficient approval pathways can lead to faster and less expensive access for patients to innovative devices.31

There are cross-national dimensions in the initial evaluation and approval of a device when different geographies are considered. There could be concerns if lower levels of evidence for device approvals are required in some regions than others.30 Differences in approval standards may favour clustering trial sites in countries with accelerated device approval processes, which may lead in other regions to reduced clinician experience with, and hindered access to, new devices. However, early access respecting independent national decisions can be supported if it benefits patient care in that region. In sum, efficient, collaborative approaches to global evidence development will likely mitigate significant variations in evidence requirements for device approval.

Global collaboration is also particularly important for developing devices for paediatric or orphan indications. These indications usually pertain to smaller patient populations, with fewer treatment options, and have minimal clinical trial evidence.

A system for cross-jurisdictional approvals, which has also been called inter-country ‘reliance’, would be beneficial to all medical device stakeholders. The MDCG recommends adherence to ISO 14155:2020 Clinical Investigation of Medical Devices for Human Subjects, but it is not mandatory according to the MDR. Although these guidelines help to achieve universally recognized standards, specific harmonization initiatives would be helpful across device clinical trials. Fortunately, such initiatives are currently underway and firmly supported by the medical community (Table 4).

Examples of global harmonization initiatives for medical device regulatory approval

| Group . | Details of membership and history . |

|---|---|

| International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) |

|

| Global Harmonization Working Party (GHWP) |

|

| Harmonization By Doing (HBD) |

|

| Group . | Details of membership and history . |

|---|---|

| International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) |

|

| Global Harmonization Working Party (GHWP) |

|

| Harmonization By Doing (HBD) |

|

Examples of global harmonization initiatives for medical device regulatory approval

| Group . | Details of membership and history . |

|---|---|

| International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) |

|

| Global Harmonization Working Party (GHWP) |

|

| Harmonization By Doing (HBD) |

|

| Group . | Details of membership and history . |

|---|---|

| International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) |

|

| Global Harmonization Working Party (GHWP) |

|

| Harmonization By Doing (HBD) |

|

The CRT workshop participants suggested that EU regulators could collaborate with the FDA and the ESC in a pilot project focused on CV device review policies and practices, as has been developed between the FDA and Japan. The US-Japan joint regulatory convergence programme, called Harmonization By Doing (HBD), is an academic, governmental, and industrial consortium that has been operative since 2003,32 with ‘HBD-for-Children’ established in 2016.33 HBD has seen success in CV device trials and post-market registries, as well as in study infrastructure, methodologies and communications.32,34,35 The programme has included global CV device clinical trials using a single trial protocol resulting in data accepted by both the US FDA and Japan’s PMDA.32,33 Overall, HBD has demonstrated efficient and viable pathways for bringing CV devices to market through the collection of harmonized clinical data and simultaneous regulatory applications in both countries.36 Further, data from clinical trials conducted in Japan have been used to support FDA approval of some devices, such as drug-eluting coronary stents, and vice versa.37,38

Another area in need of harmonizing efforts is that of global regulatory standards related to the assessment of evidence supporting the adoption of mobile health (mHealth) solutions. The ESC Regulatory Affairs Committee published a clinical consensus statement on this topic in 2024.39 The consensus proposed criteria that clinicians could use to evaluate mHealth solutions for diagnostic, therapeutic, follow-up, and educational purposes.

Expediting access for orphan medical devices and devices for use in rare diseases

Developing priority pathways in the EU for innovative devices would expedite patients’ access to devices for rare diseases. The prevalence or incidence used to define rare diseases varies across jurisdictions. In June 2024, the MDCG published guidance for the clinical evaluation of orphan medical devices (MDCG 2024-10).40 ‘Orphan devices’ were defined as those for treating, diagnosing, or preventing a disease or condition that presents in ≤12 000 Europeans/year and lacks alternative treatment options, and those that have an expected clinical benefit compared to available options.40 The guidance recognises the limitations of pre-market clinical data and provides guidance for legacy orphan devices, including the potential for generating new clinical data in the post-market phase following Ce-marking. In parallel to the publication of the guidance, the EMA Expert Panels have now extended their activities to offer specific advice to manufacturers on orphan device status regarding the new definition, the intended clinical development strategies, proposed clinical investigations, or data required for clinical evaluation during conformity assessment.41

Devices for orphan indications have unique market dynamics. The costs of development, production, clinical evaluation, and regulatory assessment often lead to a limited return on investment for manufacturers.42 Therefore, innovation of paediatric and orphan devices lags behind provision for adults with common conditions. Furthermore, previously approved orphan devices are in danger of being withdrawn from the EU market, due in part to the MDR recertification policies and the associated requirements for increased clinical data, as well as to costs and long approval times.

There are specific challenges associated with generating clinical evidence for orphan devices. Only small populations of patients are available to enrol in clinical trials, and long approval processes may have major negative impacts on these vulnerable patients due to the lack of therapeutic alternatives. A global approach may help facilitate access while maintaining high safety standards.

Clinical evidence for orphan devices can be generated both pre- and post-market. Clinical development phases are very product-dependent, and devices, particularly permanent implants, can have irreversible effects on patients. The MDR requirement for increased PMCF is a substantial challenge, especially for SMEs, because it entails ongoing maintenance and resources from manufacturers throughout the device's market lifetime. The creation of a central body to coordinate long-term monitoring of medical devices could help address these issues. One option is public and industry-funded global registries and trials for devices intended for orphan diseases/conditions. This will help overcome the issue of small numbers of patients, which impede the collection of adequate data. As many manufacturers market their devices globally, all patients could be enrolled in international registries.

Among the programmes funded by the European Commission to support the implementation of the MDR and IDVR are specific initiatives targeting innovative and orphan devices (Table 5). These initiatives are primarily part of the EU4Health programme and include the orphan device support programme (especially for paediatrics), and horizon scanning for medical devices. In terms of the legislative framework and future potential adapted pathways, orphan devices have been highlighted for attention as part of the targeted evaluation of the MDR by the European Commission.

Ongoing actions by the European Commission to support the implementation of the MDR and IDVR, including programmes targeting innovative and orphan devices

| Targets . | Actions . |

|---|---|

| Action to increase NB capacity and help prepare manufacturers |

|

| Studies to assess the regulatory framework and transition (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for infrastructure and processes (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for innovation and to address special needs |

|

| Targets . | Actions . |

|---|---|

| Action to increase NB capacity and help prepare manufacturers |

|

| Studies to assess the regulatory framework and transition (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for infrastructure and processes (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for innovation and to address special needs |

|

Based on reference.43

IVDR, in vitro diagnostics regulation; MDCG, Medical Device Coordination Group; MDR, medical device regulation; NB, Notified Bodies; SMEs, small and medium-sized enterprises.

Ongoing actions by the European Commission to support the implementation of the MDR and IDVR, including programmes targeting innovative and orphan devices

| Targets . | Actions . |

|---|---|

| Action to increase NB capacity and help prepare manufacturers |

|

| Studies to assess the regulatory framework and transition (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for infrastructure and processes (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for innovation and to address special needs |

|

| Targets . | Actions . |

|---|---|

| Action to increase NB capacity and help prepare manufacturers |

|

| Studies to assess the regulatory framework and transition (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for infrastructure and processes (EU4HEALTH) |

|

| Support for innovation and to address special needs |

|

Based on reference.43

IVDR, in vitro diagnostics regulation; MDCG, Medical Device Coordination Group; MDR, medical device regulation; NB, Notified Bodies; SMEs, small and medium-sized enterprises.

Summary

The ESC is deeply involved in advocacy to refine device regulatory systems and facilitate patient access to safe and effective innovative CV medical technology. An important goal is to support the development of a single EU regulatory mechanism or agency for devices to harmonise requirements throughout the European market and facilitate access to innovative products for patients in need. Another dimension for such a centralized agency could be to engage in dialogue with other jurisdictions, to leverage global research efforts in support of more efficient approvals of innovative devices, to the benefit of clinical care in the EU. Short- and mid-term steps include evolving the current system into a more efficient, predictable, cost-effective, and user-friendly service.

In the short term, prevention of essential device shortages is a top priority, particularly for those for paediatric and orphan patient groups, but increasingly also for devices used during more everyday procedures such as heart catheterization and electrophysiological procedures.44 Specifically, a system for more efficient and pragmatic regulation for critical devices that are about to disappear from the market will help assure continued patient access. The MDR/IVDR processes should continue to be evaluated with input from all relevant stakeholder groups.

Priorities for ESC advocacy to facilitate device access in Europe over the mid- and longer-term are shown in Table 6 and the Graphical Abstract. Strategies that could be beneficial include consideration of a pilot programme for joint approval processes of selected CV devices in partnership with the FDA (such as a ‘HBD–EU’); priority pathways; and possibly advocating with the HEU-EFS to promote EFS in the EU. More frequent use of certificates under conditions for orphan and innovative devices could be considered. The evolution of the recertification process, with a focus on making requirements proportionate to risks and on reducing the burden for SMEs, seems to be of importance. Finally, future efforts should also include facilitation of hospital-based reprocessing of single-use devices and guidance on the use of medical software.

Mid- and long-term goals for ESC advocacy to address ongoing issues with the transition to MDR/IVDR and facilitate innovation in Europe

Mid-term goals

|

Long-term goals

|

Mid-term goals

|

Long-term goals

|

Mid- and long-term goals for ESC advocacy to address ongoing issues with the transition to MDR/IVDR and facilitate innovation in Europe

Mid-term goals

|

Long-term goals

|

Mid-term goals

|

Long-term goals

|

Acknowledgements

This article was generated from discussions during a Cardiovascular Round Table (CRT) event organized in April 2024 by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). The ESC CRT is a strategic forum for high-level dialogue between 20 industry companies (pharmaceutical, devices, and diagnostics) and the ESC leadership to identify and discuss key strategic issues for the future of cardiovascular health in Europe. The full agenda, as well as videos of the session, can be viewed online (https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/What-we-do/Cardiovascular-Round-Table-(CRT)/Events/cardiovascular-round-table-crt-plenary-2024). The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this manuscript, which do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the institution to which the authors are affiliated. The authors would like to thank Pauline Lavigne and Steven Portelance (unaffiliated, supported by the ESC) for contributions to writing, and editing the manuscript. The authors would also like to acknowledge the significant contributions of Dr. Andrew Farb, Dr. Changfu Wu, and Dr. Bram Zuckerman of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration during the CRT.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are not available at European Heart Journal online.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

S.W.: Institutional grants from Abbott, Abiomed, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Bbraun, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardinal Health, CardioValve, Cleerly Inc., Cordis Medical, Corflow Therapeutics, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Farapulse Inc., Fumedica, GE Medical Systems, Gebro Pharma, Guerbet, Idorsia, Inari Medical, InfraRedx, Janssen-Cilag, Johnson & Johnson, Medalliance, Medicure, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Miracor Medical, Neucomed, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Organon, OrPha Suisse, Pharming Tech, Pfizer, Philips AG, Polares, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Siemens Healthcare, Sinomed, SMT Sahajanand Medical Technologies, Terumo, Vifor, V-Wave, and Zoll Medical; payment or honoraria paid to the institution for participation in educational events from Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, and Abbott; direct payment to the institution (no personal payment received) for advisory board participation and/or steering/executive committee membership for trials funded by Abbott, Abiomed, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Bristol Myers Squibb, Edwards Lifesciences, MedAlliance, Medtronic, Novartis, Polares, Recardio, Sinomed, Terumo, and V-Wave; participation on the selection committee for the Pfizer Research Award in Switzerland (unpaid member), with the Clinical Study Group of the Deutsches Zentrum für Herz Kreislauf-Forschung (expert panel member), and on the Global Cardiovascular Research Funder Forum (expert panel member); and leadership roles with the European Society of Cardiology (Vice-President) and for the PCR EAPCI Textbook on Cardiovascular Medicine (editor). A.G.F.: Support for meeting attendance and/or travel from the European Society of Cardiology; and a leadership role (Chair) on the Regulatory Affairs Committee of the Biomedical Alliance in Europe. M.G.: None. T.F.L.: Institutional grants from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Vifor; consulting fees from Milestone Pharmaceuticals and Novo Nordisk; and leadership roles with the European Society of Cardiology (President), the Zürich Heart House—Foundation for CV Research (President), the Swiss Heart Foundation (research committee Chairman), and the London Heart House (Trustee). P.S.: Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, or speakers bureau participation from Samsung Medical, Novartis, and GE. L.A.: None. J.B.: Employment with Medtronic; stock or options from Medtronic. R.B.: Institutional grants from Abbott Vascular, Biosensors, Boston Scientific, and Translumina. L.C.: None. I.D.: None. J.F.: Employment with Philips; stock or stock options from Philips, Eli Lilly, Fresenius SE, Medtronic, Moderna, and Takeda; and participation on an advisory board for Oska Health Medical GmbH (unpaid). M.G.C. Employment with the European Commission services as a Legal and Policy Officer for EU Regulations on medical devices and in vitro diagnostic medical devices. A.J.K.: Institutional funding paid to Columbia University and/or the Cardiovascular Research Foundation from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Amgen, CSI, Philips, ReCor Medical, Neurotronic, Biotronik, Chiesi, Bolt Medical, Magenta Medical, Canon, SoniVie, Shockwave Medical, and Merck; consulting fees from IMDS; and support for meeting attendance and/or travel from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, CSI, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, Chiesi, OpSens, Zoll, and Regeneron. J.K.: Employment with Edwards Lifesciences; stock options from Edwards Lifesciences. M.K.: Grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Biosensors, Boston Scientific, Celonova, Medtronic, and OrbusNeich. G.M.: Support for meeting attendance and/or travel from the European Society of Cardiology. P.O.M.: leadership roles with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (Councilor, Secretary General), CTSNet (President), and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (International Director). D.B.O.: Support for meeting attendance and/or travel from the European Society of Cardiology. R.P.: Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, or speakers bureau participation from Edwards Lifesciences. P.P.: None. Ar.R.: Consulting fees from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Philips; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, or speakers bureau participation from Abbott, Medtronic, and Philips; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Medtronic. A.R.: Employment with Edwards Lifesciences; stock options from Edwards Lifesciences. G.S.: None. E.S.: Employment with GE HealthCare; stock or options from GE HealthCare. A.V.: Employment with Medtronic; stock or options from Medtronic. R.S.v.B. Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, or speakers bureau participation from Abbott Structural, Medtronic, and Edwards Lifesciences; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Medtronic; and is an member of the Heart Valve Society USA board (unpaid) and the EU SHD Coalition Steering Committee (unpaid). F.W.: None.

Data availability

No data were generated or analyzed for or in support of this paper.

Funding

This report was funded as part of the work of the Cardiovascular Round Table (CRT). The CRT is funded thanks to multi-sponsorship. Learn more at https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/What-we-do/Cardiovascular-Round-Table-(CRT).