-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Philip Moons, Tone M Norekvål, Elena Arbelo, Britt Borregaard, Barbara Casadei, Bernard Cosyns, Martin R Cowie, Donna Fitzsimons, Alan G Fraser, Tiny Jaarsma, Paulus Kirchhof, Josepa Mauri, Richard Mindham, Julie Sanders, Francois Schiele, Aleksandra Torbica, Ann Dorthe Zwisler, Placing patient-reported outcomes at the centre of cardiovascular clinical practice: implications for quality of care and management: A statement of the ESC Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), the Association for Acute CardioVascular Care (ACVC), European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), Heart Failure Association (HFA), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI), ESC Regulatory Affairs Committee, ESC Advocacy Committee, ESC Digital Health Committee, ESC Education Committee, and the ESC Patient Forum, European Heart Journal, Volume 44, Issue 36, 21 September 2023, Pages 3405–3422, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad514

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) provide important insights into patients’ own perspectives about their health and medical condition, and there is evidence that their use can lead to improvements in the quality of care and to better-informed clinical decisions. Their application in cardiovascular populations has grown over the past decades. This statement describes what PROs are, and it provides an inventory of disease-specific and domain-specific PROs that have been developed for cardiovascular populations. International standards and quality indices have been published, which can guide the selection of PROs for clinical practice and in clinical trials and research; patients as well as experts in psychometrics should be involved in choosing which are most appropriate. Collaborations are needed to define criteria for using PROs to guide regulatory decisions, and the utility of PROs for comparing and monitoring the quality of care and for allocating resources should be evaluated. New sources for recording PROs include wearable digital health devices, medical registries, and electronic health record. Advice is given for the optimal use of PROs in shared clinical decision-making in cardiovascular medicine, and concerning future directions for their wider application.

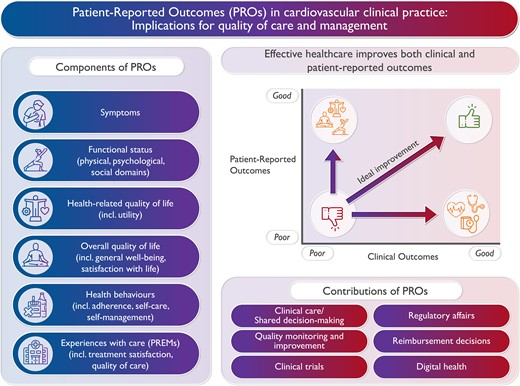

The importance of patient-reported outcomes (PROs), their components, and their potential contributions in cardiology.

Introduction

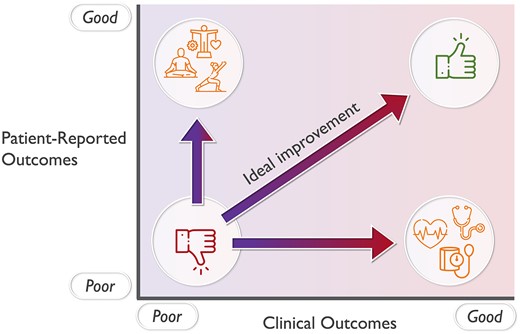

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are increasingly used as a standardized means of integrating and reporting patients’ own perspectives in the assessment of their health and medical condition. PROs are typically defined as ‘any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else’.1 Combined with clinical outcomes, PROs reflect the totality of outcomes of care in patients. Ideally, healthcare aims at improving both clinical outcomes and PROs (Figure 1).2

Effective healthcare improves both clinical and patient-reported outcomes.

Whereas PROs were initially used for descriptive clinical research and population-based surveys, they gradually found their way into clinical practice.3,4 PROs are of particular importance for the monitoring and management of chronic conditions affecting quality of life. They can be used for individual assessment to support decisions and to evaluate aspects of quality of care.5–8 To support the use of PROs in the routine clinical setting, electronic- or ePROs have been developed recently, and real-time data collection is gaining more traction.9 Moreover, PROs are increasingly used to assess treatments and interventions in clinical trials, informing regulatory and reimbursement decisions for drugs and medical devices.10–14 However, the use of PROs is not without methodological challenges; there are gaps between the underpinning evidence and the current practical implementation, which challenges their use and interpretation.15,16

Papers advocating for the use of PROs in the field of cardiology have been published by the American Heart Association (AHA) in 201317 and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in 2014.18 The AHA statement advocated for the assessment of patient-reported health status as a measure of cardiovascular health,17 whereas the ESC document was a call for a more comprehensive integration of PROs in cardiovascular trials.18 Given recent developments and the continuous expansion of PROs in the clinical arena, this present statement aims to define what PROs are, to describe how they can be measured in cardiovascular populations, and to discuss how PROs can be further integrated into cardiovascular research, clinical practice, and regulatory and reimbursement decisions. Although this statement specifically addresses the use of PROs in cardiovascular populations, the topics discussed are relevant for other conditions and specialities as well.

Development of this statement

This statement was developed in an iterative way. First, the consensus panel/writing group was formed by identifying all relevant and important ESC constituent bodies, and ensuring the representation of these bodies in the writing group. Second, the writing group has met and the different sections to be included in the statement were determined. Third, mini-teams were formed to write each of the sections. The content of the different sections was based on the expertise of the panel members and the relevant literature in the domain. Fourth, the different sections were compiled and integrated. Parts were rewritten to avoid overlap between the sections, and to obtain a common writing style. Fifth, gaps or inconsistencies in the message were dealt with by the chairs of the writing group. Sixth, the entire statement was reviewed and revised by the writing group in two consecutive iterations. Seventh, the document was finalized and approval from the entire writing group was obtained. Eighth, the statement was submitted to the participating associations/councils/committee for review and approval.

What are PROs?

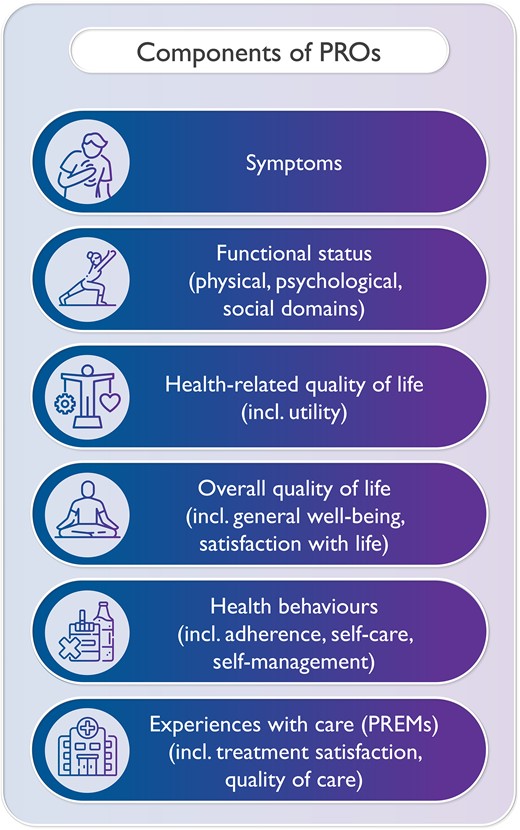

Although the definition of PROs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as cited above, is widely accepted, there is less consensus on the components of PROs. According to this definition, PROs pertain to the status of a patient's health condition as directly reported by the patient.1 Such patient-reported health status may include symptoms, functional status, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (Figure 2).17 One of the earliest frameworks on PROs suggested that other outcomes, in addition to patient-reported health, are relevant such as global impression and well-being (which reflect the overall quality of life), adherence to therapies and healthy lifestyles (which reflect health behaviours), and satisfaction with the treatment (which reflect experiences with care) (Figure 2).19 These extensions led to the following definition of PROs: ‘any report of the status of a patient’s health condition, health behaviour, or experience with healthcare that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else’.20,21 This extended definition was the first one that explicitly included patient experiences as PROs. Importantly, patient experiences here refer to experiences with the care processes, and do not pertain to the hospitality function of healthcare facilities. Patient experiences can be measured using patient-reported experience measures (PREMs: see below).

It is important to clarify that not all the information that is provided by patients can be viewed as PROs. For instance, data from wearables, such as activity trackers, could be construed as patient-generated outcomes, rather than PROs. Further, feedback from patients provided as free text, although important, is also not a PRO.

How are PROs measured?

PROs are typically measured using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). However, given that experiences with healthcare are also considered as a PRO (see above), PREMs should be seen as an additional measure to assess PROs, next to PROMS.

There are three types of PROMs: generic, disease-specific, and domain-specific instruments.5 It is advised that these types of PROMs are used in combination as they provide complementary information.22 Generic PROMs comprise questions that are general in nature and therefore can be used in any population of respondents. Such generic PROMs are mostly chosen when comparing different patient populations, patients with different levels of comorbidities, or when comparing a patient group with healthy controls. Generic PROMs are typically multidimensional and cover a broad range of functional domains, such as mobility, emotions, or self-care. Examples of widely used generic PROMs are the EuroQol-5 dimension,23 the SF-36,24 or PROMIS.25

Disease-specific PROMs are used when outcomes relating to a specific condition are of interest. Such instruments are often more sensitive than generic PROMs when used in a particular patient population, because they can be more focused and detailed. Most disease-specific PROMs are multidimensional, such as the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLHF) Questionnaire26 or the Myocardial Infarction Dimensional Assessment Scale (MIDAS).27

Domain-specific PROMs cover a specific symptom or issue. Since they measure a single phenomenon or construct, they are often, but not always, unidimensional and narrow in scope, but they can have varying levels of depth. An example of a domain-specific PROM with little depth is the unidimensional visual analogue scale for pain intensity.28 By contrast, the McGill Pain Questionnaire is a multidimensional domain-specific PROM of greater depth, that is designed to measure the sensory, affective, and evaluative aspects of pain and its intensity.28 Some domain-specific PROMs are also disease-specific (e.g. health behaviours in congenital heart disease.29)

PROMs for particular cardiovascular diseases

An early standardized questionnaire that was used to assess cardiovascular symptoms was the one on angina pectoris that was developed and validated by Geoffrey Rose and published by the World Health Organization in 1962.30 Nowadays, it is considered to be the first instrument to document PRO. Since then, a plethora of disease-specific PROMs has been developed to assess symptomatic burden, functional status or quality of life in diverse cardiovascular conditions, such as ischemic heart disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, cardiac surgery, heart transplantation, and congenital heart disease. Table 1 provides an inventory of cardiac-specific PROMs. Most of these PROMs are multidimensional, whereas others measure a single construct, such as behaviour. These disease-specific measures allow researchers and clinicians to measure PROs in a more sensitive fashion than when using generic measures. For some instruments, extensive and short versions are available. Several reviews and in-depth evaluations on cardiac-specific PROMs have been published over the past years, including reviews that scrutinized and compared the psychometric properties of different instruments.33,45,46,51,97,100,103,128,139,143–145 Based on the findings of these reviews, we provide summary information on the level of support for each individual instrument (Table 1). First, we checked whether the systematic reviews evaluated the instruments under study according to the COSMIN standards (see below). Second, for those reviews that did evaluate the standards, we determined whether all, most, or only some of the standards were met. Meeting all of the standards provides the strongest support for using these particular instruments. If the psychometric properties of the instruments have not yet been evaluated in systematic reviews, this indicates a need for further research rather than a reason to avoid using them.

Disease-specific PROMs (multidimensional or domain-specific) developed for cardiovascular patient populations

| Name . | Domain . | Developed for . | Level of support . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac patients | |||

| Cardiac Event Threat Questionnaire (CTQ)31 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Health Profile (CHP)32 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| LifeWare Cardiac Assessment Index (LIFEWARE CAI)34 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Multidimensional Index of Life Quality (MILQ)35 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index-Cardiac Version (QLI-CV)36 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Duke Activity Status Index (DASI)37 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Specific Activity Scale38 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac anxiety questionnaire39 | Anxiety | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Depression Scale (CDS)40 | Depression | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac distress inventory41 | Psychological functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Arrhythmias and electrophysiology | |||

| Patient Perception of Arrhythmia Questionnaire (PPAQ)42 | Multidimensional | Arrhythmias | −33 |

| AF643,44 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,46 |

| AFImpact47 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33 |

| AF-QoL48 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Effect on QualiTy-of-Life (AFEQT)49 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | +33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Quality of Life Questionnaire (AFQLQ)50 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,51 |

| Quality of life in AF patients (QLAF)52 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| University of Toronto Atrial Fibrillation Severity Scale (AFSS)53 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −46,51 |

| Cardiff Cardiac Ablation PROM (C-CAP)54,55 | Multidimensional | Pre- and post-ablation | / |

| Arrhythmia-Specific questionnaire in Tachycardia and Arrhythmia (ASTA)56 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −33,46,51 |

| Umeå 22 Arrhythmia Questions (U22)57 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −46 |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society-Severity of Atrial Fibrillation (CCS-SAF)58 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Mayo Atrial Fibrillation-Specific Symptom Inventory (MAFSI)59 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Symptom Checklist—Frequency and Severity Scale (SCL) aka Toronto AF Symptoms Check List60 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −51 |

| Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviour questionnaire to patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation61 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| Knowledge and self-management tool62 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| VALIOSA (Satisfaction with remote cardiac monitoring)63 | Experience with care | Implanted cardiac devices | / |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||

| Modified Postoperative Recovery Profile questionnaire re (PRP-CABG)64 | Multidimensional | CABG | / |

| Coronary Revascularisation Outcome Questionnaire (CROQ)65 | Multidimensional | CABG or PTCA | +33 |

| Angina Pectoris Quality of Life Questionnaire (APQLQ)66 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Cardiovascular Limitations and Symptoms Profile (CLASP)67 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Health Complaints Scale (HCS)68 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | −33 |

| HeartQol69,70 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index (QLI)71 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Coronary Heart Disease (QLICD-CHD)72 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ19)73 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Short version of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ7)74 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Summary Index for the Assessment of Quality of Life in Angina Pectoris75 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| MacNew Heart Disease Questionnaire (aka QLMI-2)76 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | ++33 |

| Myocardial Infarction Dimensional Assessment Scale (MIDAS)27 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLMI)77 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | / |

| Cardiac Surgery Symptom Inventory (CSSI)78 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Cardiac Symptom Survey (CSS)79 | Symptoms | CABG | −46 |

| Heart Surgery Symptom Inventory (HSSI)80 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Symptoms of Illness Score (SOIS)81 | Symptoms | CABG/valve surgery | / |

| Symptom Inventory82 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery | / |

| Cardiac Symptoms Scale83 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery/PTCA | / |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) symptom checklist84 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS)85 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | −46 |

| Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndrome Inventory (SACSI)86 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| Symptom Scale87 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Shortened WHO Rose Angina Questionnaire88 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| WHO Rose angina questionnaire30 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Angina-related Limitations at Work Questionnaire (ALWQ)89 | Work-related functioning | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Congenital heart disease | |||

| ACHD PRO, Adult Congenital Heart Disease—Patient-Reported Outcome90 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | +33 |

| Congenital Heart Disease—TNO/AZL Adult Quality Of Life (CHD-TAAQOL)91 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | −33 |

| PedsQl cardiac module92 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Pediatric Cardiac QOL Inventory93 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Congenital Heart Adolescent and Teenager Questionnaire (CHAT)94 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| ConQol95 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Health Behavior Scale—Congenital Heart Disease29 | Behaviour | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Heart failure and transplantation | |||

| Cardiac Health Profile of Congestive Heart Failure (CHPchf)96 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −97 |

| Care-Related Quality of Life survey for Chronic Heart Failure (CaReQol CHF)98 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Assessment Tool (CHAT)99 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100 |

| Chronic Heart Failure-PRO Measure (CHF-PROM)101 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire (CHQ/CHFQ)102 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100,103 |

| Heart Failure-Functional Status Assessment (HF-FSA)104 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Heart Failure Symptom Checklist105 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)106 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | ++33,97 |

| Knowledge, attitude, self-care practice and HRQoL of Heart Failure patients (KAPQ-HF)107 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Left Ventricular Dysfunction Questionnaire (LVD-36)108 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,100,103 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Inventory e Heart Failure (MDASI-HF)109 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLHF)26 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,97,100,103 |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Plus-Heart Failure (PROMIS-Plus-HF)110 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire in Severe Heart Failure (QLQ-SHF)111 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,103 |

| Short version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-12)112 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine inquiry (TCM inquiry)113 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Heart Transplant Stressor Scale114 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rating Question Form115 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rotterdam Quality of Life Questionnaire116 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| LVAD Stressor Scale (modified)117 | Multidimensional | LVAD | / |

| Quality of Life with a Ventricular Assistive Device Questionnaire (QOLVAD)118 | Multidimensional | LVAD | −33 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Awareness Scale (HFSAS)119 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale (HFSPS)120 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Heart Failure (MSAS-HF)121 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| San Diego Heart Failure Questionnaire (SDHFQ)122 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| Symptom Checklist (SCL)123 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Symptom Status Questionnaire—Heart Failure (SSQ-HF)124 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Heart Failure Functional Status Inventory (HFFSI)125 | Symptoms; Functional capabilities | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS)126,127 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128,129 |

| Evaluation Scale for Self-monitoring by Patients with Chronic Heart Failure (ESSMHF)130 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Self-care of Heart Failure Index (SCHFI)131 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128 |

| Spiritual Self-care Practice Scale (SSCPS)132 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Valvular diseases | |||

| Heart Valve Disease Impact on daily life (IDCV)133 | Multidimensional | Heart valve disease | −33 |

| Toronto Aortic Stenosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (TASQ)134 | Multidimensional | SAVR/TAVI | −33 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Impact of Syncope on Quality of Life (ISQL)135 | Multidimensional | Syncope | −33 |

| Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ)136 | Multidimensional | Hypotension | +33 |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Hypertension (QLICH-HY)137 | Multidimensional | Hypertension | |

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale138 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Treatment Adherence Questionnaire for Patients with Hypertension (TAQPH)140 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Therapeutic Adherence Scale for Hypertensive Patients (TASHP)141 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Hypertension Self-Care Profile (HBP SCP)142 | Self-care | Hypertension | / |

| Name . | Domain . | Developed for . | Level of support . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac patients | |||

| Cardiac Event Threat Questionnaire (CTQ)31 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Health Profile (CHP)32 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| LifeWare Cardiac Assessment Index (LIFEWARE CAI)34 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Multidimensional Index of Life Quality (MILQ)35 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index-Cardiac Version (QLI-CV)36 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Duke Activity Status Index (DASI)37 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Specific Activity Scale38 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac anxiety questionnaire39 | Anxiety | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Depression Scale (CDS)40 | Depression | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac distress inventory41 | Psychological functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Arrhythmias and electrophysiology | |||

| Patient Perception of Arrhythmia Questionnaire (PPAQ)42 | Multidimensional | Arrhythmias | −33 |

| AF643,44 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,46 |

| AFImpact47 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33 |

| AF-QoL48 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Effect on QualiTy-of-Life (AFEQT)49 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | +33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Quality of Life Questionnaire (AFQLQ)50 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,51 |

| Quality of life in AF patients (QLAF)52 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| University of Toronto Atrial Fibrillation Severity Scale (AFSS)53 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −46,51 |

| Cardiff Cardiac Ablation PROM (C-CAP)54,55 | Multidimensional | Pre- and post-ablation | / |

| Arrhythmia-Specific questionnaire in Tachycardia and Arrhythmia (ASTA)56 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −33,46,51 |

| Umeå 22 Arrhythmia Questions (U22)57 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −46 |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society-Severity of Atrial Fibrillation (CCS-SAF)58 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Mayo Atrial Fibrillation-Specific Symptom Inventory (MAFSI)59 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Symptom Checklist—Frequency and Severity Scale (SCL) aka Toronto AF Symptoms Check List60 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −51 |

| Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviour questionnaire to patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation61 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| Knowledge and self-management tool62 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| VALIOSA (Satisfaction with remote cardiac monitoring)63 | Experience with care | Implanted cardiac devices | / |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||

| Modified Postoperative Recovery Profile questionnaire re (PRP-CABG)64 | Multidimensional | CABG | / |

| Coronary Revascularisation Outcome Questionnaire (CROQ)65 | Multidimensional | CABG or PTCA | +33 |

| Angina Pectoris Quality of Life Questionnaire (APQLQ)66 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Cardiovascular Limitations and Symptoms Profile (CLASP)67 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Health Complaints Scale (HCS)68 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | −33 |

| HeartQol69,70 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index (QLI)71 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Coronary Heart Disease (QLICD-CHD)72 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ19)73 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Short version of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ7)74 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Summary Index for the Assessment of Quality of Life in Angina Pectoris75 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| MacNew Heart Disease Questionnaire (aka QLMI-2)76 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | ++33 |

| Myocardial Infarction Dimensional Assessment Scale (MIDAS)27 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLMI)77 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | / |

| Cardiac Surgery Symptom Inventory (CSSI)78 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Cardiac Symptom Survey (CSS)79 | Symptoms | CABG | −46 |

| Heart Surgery Symptom Inventory (HSSI)80 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Symptoms of Illness Score (SOIS)81 | Symptoms | CABG/valve surgery | / |

| Symptom Inventory82 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery | / |

| Cardiac Symptoms Scale83 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery/PTCA | / |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) symptom checklist84 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS)85 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | −46 |

| Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndrome Inventory (SACSI)86 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| Symptom Scale87 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Shortened WHO Rose Angina Questionnaire88 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| WHO Rose angina questionnaire30 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Angina-related Limitations at Work Questionnaire (ALWQ)89 | Work-related functioning | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Congenital heart disease | |||

| ACHD PRO, Adult Congenital Heart Disease—Patient-Reported Outcome90 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | +33 |

| Congenital Heart Disease—TNO/AZL Adult Quality Of Life (CHD-TAAQOL)91 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | −33 |

| PedsQl cardiac module92 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Pediatric Cardiac QOL Inventory93 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Congenital Heart Adolescent and Teenager Questionnaire (CHAT)94 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| ConQol95 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Health Behavior Scale—Congenital Heart Disease29 | Behaviour | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Heart failure and transplantation | |||

| Cardiac Health Profile of Congestive Heart Failure (CHPchf)96 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −97 |

| Care-Related Quality of Life survey for Chronic Heart Failure (CaReQol CHF)98 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Assessment Tool (CHAT)99 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100 |

| Chronic Heart Failure-PRO Measure (CHF-PROM)101 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire (CHQ/CHFQ)102 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100,103 |

| Heart Failure-Functional Status Assessment (HF-FSA)104 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Heart Failure Symptom Checklist105 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)106 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | ++33,97 |

| Knowledge, attitude, self-care practice and HRQoL of Heart Failure patients (KAPQ-HF)107 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Left Ventricular Dysfunction Questionnaire (LVD-36)108 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,100,103 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Inventory e Heart Failure (MDASI-HF)109 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLHF)26 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,97,100,103 |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Plus-Heart Failure (PROMIS-Plus-HF)110 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire in Severe Heart Failure (QLQ-SHF)111 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,103 |

| Short version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-12)112 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine inquiry (TCM inquiry)113 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Heart Transplant Stressor Scale114 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rating Question Form115 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rotterdam Quality of Life Questionnaire116 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| LVAD Stressor Scale (modified)117 | Multidimensional | LVAD | / |

| Quality of Life with a Ventricular Assistive Device Questionnaire (QOLVAD)118 | Multidimensional | LVAD | −33 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Awareness Scale (HFSAS)119 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale (HFSPS)120 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Heart Failure (MSAS-HF)121 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| San Diego Heart Failure Questionnaire (SDHFQ)122 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| Symptom Checklist (SCL)123 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Symptom Status Questionnaire—Heart Failure (SSQ-HF)124 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Heart Failure Functional Status Inventory (HFFSI)125 | Symptoms; Functional capabilities | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS)126,127 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128,129 |

| Evaluation Scale for Self-monitoring by Patients with Chronic Heart Failure (ESSMHF)130 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Self-care of Heart Failure Index (SCHFI)131 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128 |

| Spiritual Self-care Practice Scale (SSCPS)132 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Valvular diseases | |||

| Heart Valve Disease Impact on daily life (IDCV)133 | Multidimensional | Heart valve disease | −33 |

| Toronto Aortic Stenosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (TASQ)134 | Multidimensional | SAVR/TAVI | −33 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Impact of Syncope on Quality of Life (ISQL)135 | Multidimensional | Syncope | −33 |

| Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ)136 | Multidimensional | Hypotension | +33 |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Hypertension (QLICH-HY)137 | Multidimensional | Hypertension | |

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale138 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Treatment Adherence Questionnaire for Patients with Hypertension (TAQPH)140 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Therapeutic Adherence Scale for Hypertensive Patients (TASHP)141 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Hypertension Self-Care Profile (HBP SCP)142 | Self-care | Hypertension | / |

AF, Atrial Fibrillation; CABG, Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; DS, domain-specific; ICD, Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator; LVAD, Left Ventricular Assist Device; PTCA, Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty; SC, Single construct; SAVR, Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement; TAVI, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Level of support; /, psychometric properties not evaluated any systematic review; −, the cited systematic review indicated that none or only some of the psychometric properties of this instrument have met COSMIN standards; +, systematic review indicated support for most psychometric properties; ++, systematic review indicated support for all psychometric properties.

Disease-specific PROMs (multidimensional or domain-specific) developed for cardiovascular patient populations

| Name . | Domain . | Developed for . | Level of support . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac patients | |||

| Cardiac Event Threat Questionnaire (CTQ)31 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Health Profile (CHP)32 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| LifeWare Cardiac Assessment Index (LIFEWARE CAI)34 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Multidimensional Index of Life Quality (MILQ)35 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index-Cardiac Version (QLI-CV)36 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Duke Activity Status Index (DASI)37 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Specific Activity Scale38 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac anxiety questionnaire39 | Anxiety | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Depression Scale (CDS)40 | Depression | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac distress inventory41 | Psychological functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Arrhythmias and electrophysiology | |||

| Patient Perception of Arrhythmia Questionnaire (PPAQ)42 | Multidimensional | Arrhythmias | −33 |

| AF643,44 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,46 |

| AFImpact47 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33 |

| AF-QoL48 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Effect on QualiTy-of-Life (AFEQT)49 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | +33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Quality of Life Questionnaire (AFQLQ)50 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,51 |

| Quality of life in AF patients (QLAF)52 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| University of Toronto Atrial Fibrillation Severity Scale (AFSS)53 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −46,51 |

| Cardiff Cardiac Ablation PROM (C-CAP)54,55 | Multidimensional | Pre- and post-ablation | / |

| Arrhythmia-Specific questionnaire in Tachycardia and Arrhythmia (ASTA)56 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −33,46,51 |

| Umeå 22 Arrhythmia Questions (U22)57 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −46 |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society-Severity of Atrial Fibrillation (CCS-SAF)58 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Mayo Atrial Fibrillation-Specific Symptom Inventory (MAFSI)59 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Symptom Checklist—Frequency and Severity Scale (SCL) aka Toronto AF Symptoms Check List60 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −51 |

| Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviour questionnaire to patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation61 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| Knowledge and self-management tool62 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| VALIOSA (Satisfaction with remote cardiac monitoring)63 | Experience with care | Implanted cardiac devices | / |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||

| Modified Postoperative Recovery Profile questionnaire re (PRP-CABG)64 | Multidimensional | CABG | / |

| Coronary Revascularisation Outcome Questionnaire (CROQ)65 | Multidimensional | CABG or PTCA | +33 |

| Angina Pectoris Quality of Life Questionnaire (APQLQ)66 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Cardiovascular Limitations and Symptoms Profile (CLASP)67 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Health Complaints Scale (HCS)68 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | −33 |

| HeartQol69,70 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index (QLI)71 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Coronary Heart Disease (QLICD-CHD)72 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ19)73 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Short version of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ7)74 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Summary Index for the Assessment of Quality of Life in Angina Pectoris75 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| MacNew Heart Disease Questionnaire (aka QLMI-2)76 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | ++33 |

| Myocardial Infarction Dimensional Assessment Scale (MIDAS)27 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLMI)77 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | / |

| Cardiac Surgery Symptom Inventory (CSSI)78 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Cardiac Symptom Survey (CSS)79 | Symptoms | CABG | −46 |

| Heart Surgery Symptom Inventory (HSSI)80 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Symptoms of Illness Score (SOIS)81 | Symptoms | CABG/valve surgery | / |

| Symptom Inventory82 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery | / |

| Cardiac Symptoms Scale83 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery/PTCA | / |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) symptom checklist84 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS)85 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | −46 |

| Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndrome Inventory (SACSI)86 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| Symptom Scale87 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Shortened WHO Rose Angina Questionnaire88 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| WHO Rose angina questionnaire30 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Angina-related Limitations at Work Questionnaire (ALWQ)89 | Work-related functioning | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Congenital heart disease | |||

| ACHD PRO, Adult Congenital Heart Disease—Patient-Reported Outcome90 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | +33 |

| Congenital Heart Disease—TNO/AZL Adult Quality Of Life (CHD-TAAQOL)91 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | −33 |

| PedsQl cardiac module92 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Pediatric Cardiac QOL Inventory93 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Congenital Heart Adolescent and Teenager Questionnaire (CHAT)94 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| ConQol95 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Health Behavior Scale—Congenital Heart Disease29 | Behaviour | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Heart failure and transplantation | |||

| Cardiac Health Profile of Congestive Heart Failure (CHPchf)96 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −97 |

| Care-Related Quality of Life survey for Chronic Heart Failure (CaReQol CHF)98 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Assessment Tool (CHAT)99 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100 |

| Chronic Heart Failure-PRO Measure (CHF-PROM)101 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire (CHQ/CHFQ)102 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100,103 |

| Heart Failure-Functional Status Assessment (HF-FSA)104 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Heart Failure Symptom Checklist105 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)106 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | ++33,97 |

| Knowledge, attitude, self-care practice and HRQoL of Heart Failure patients (KAPQ-HF)107 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Left Ventricular Dysfunction Questionnaire (LVD-36)108 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,100,103 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Inventory e Heart Failure (MDASI-HF)109 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLHF)26 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,97,100,103 |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Plus-Heart Failure (PROMIS-Plus-HF)110 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire in Severe Heart Failure (QLQ-SHF)111 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,103 |

| Short version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-12)112 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine inquiry (TCM inquiry)113 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Heart Transplant Stressor Scale114 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rating Question Form115 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rotterdam Quality of Life Questionnaire116 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| LVAD Stressor Scale (modified)117 | Multidimensional | LVAD | / |

| Quality of Life with a Ventricular Assistive Device Questionnaire (QOLVAD)118 | Multidimensional | LVAD | −33 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Awareness Scale (HFSAS)119 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale (HFSPS)120 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Heart Failure (MSAS-HF)121 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| San Diego Heart Failure Questionnaire (SDHFQ)122 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| Symptom Checklist (SCL)123 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Symptom Status Questionnaire—Heart Failure (SSQ-HF)124 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Heart Failure Functional Status Inventory (HFFSI)125 | Symptoms; Functional capabilities | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS)126,127 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128,129 |

| Evaluation Scale for Self-monitoring by Patients with Chronic Heart Failure (ESSMHF)130 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Self-care of Heart Failure Index (SCHFI)131 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128 |

| Spiritual Self-care Practice Scale (SSCPS)132 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Valvular diseases | |||

| Heart Valve Disease Impact on daily life (IDCV)133 | Multidimensional | Heart valve disease | −33 |

| Toronto Aortic Stenosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (TASQ)134 | Multidimensional | SAVR/TAVI | −33 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Impact of Syncope on Quality of Life (ISQL)135 | Multidimensional | Syncope | −33 |

| Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ)136 | Multidimensional | Hypotension | +33 |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Hypertension (QLICH-HY)137 | Multidimensional | Hypertension | |

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale138 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Treatment Adherence Questionnaire for Patients with Hypertension (TAQPH)140 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Therapeutic Adherence Scale for Hypertensive Patients (TASHP)141 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Hypertension Self-Care Profile (HBP SCP)142 | Self-care | Hypertension | / |

| Name . | Domain . | Developed for . | Level of support . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac patients | |||

| Cardiac Event Threat Questionnaire (CTQ)31 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Health Profile (CHP)32 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| LifeWare Cardiac Assessment Index (LIFEWARE CAI)34 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Multidimensional Index of Life Quality (MILQ)35 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index-Cardiac Version (QLI-CV)36 | Multidimensional | Cardiac patients | −33 |

| Duke Activity Status Index (DASI)37 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Specific Activity Scale38 | Physical functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac anxiety questionnaire39 | Anxiety | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac Depression Scale (CDS)40 | Depression | Cardiac patients | / |

| Cardiac distress inventory41 | Psychological functioning | Cardiac patients | / |

| Arrhythmias and electrophysiology | |||

| Patient Perception of Arrhythmia Questionnaire (PPAQ)42 | Multidimensional | Arrhythmias | −33 |

| AF643,44 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,46 |

| AFImpact47 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33 |

| AF-QoL48 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Effect on QualiTy-of-Life (AFEQT)49 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | +33,45 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Quality of Life Questionnaire (AFQLQ)50 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45,51 |

| Quality of life in AF patients (QLAF)52 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −33,45 |

| University of Toronto Atrial Fibrillation Severity Scale (AFSS)53 | Multidimensional | Atrial fibrillation | −46,51 |

| Cardiff Cardiac Ablation PROM (C-CAP)54,55 | Multidimensional | Pre- and post-ablation | / |

| Arrhythmia-Specific questionnaire in Tachycardia and Arrhythmia (ASTA)56 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −33,46,51 |

| Umeå 22 Arrhythmia Questions (U22)57 | Symptoms | Arrhythmias | −46 |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society-Severity of Atrial Fibrillation (CCS-SAF)58 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Mayo Atrial Fibrillation-Specific Symptom Inventory (MAFSI)59 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −46 |

| Symptom Checklist—Frequency and Severity Scale (SCL) aka Toronto AF Symptoms Check List60 | Symptoms | Atrial fibrillation | −51 |

| Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviour questionnaire to patients with Atrial Fibrillation undergoing Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation61 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| Knowledge and self-management tool62 | Self-management | Atrial fibrillation | / |

| VALIOSA (Satisfaction with remote cardiac monitoring)63 | Experience with care | Implanted cardiac devices | / |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||

| Modified Postoperative Recovery Profile questionnaire re (PRP-CABG)64 | Multidimensional | CABG | / |

| Coronary Revascularisation Outcome Questionnaire (CROQ)65 | Multidimensional | CABG or PTCA | +33 |

| Angina Pectoris Quality of Life Questionnaire (APQLQ)66 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Cardiovascular Limitations and Symptoms Profile (CLASP)67 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Health Complaints Scale (HCS)68 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | −33 |

| HeartQol69,70 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Quality of Life Index (QLI)71 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Coronary Heart Disease (QLICD-CHD)72 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ19)73 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | +33 |

| Short version of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ7)74 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Summary Index for the Assessment of Quality of Life in Angina Pectoris75 | Multidimensional | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| MacNew Heart Disease Questionnaire (aka QLMI-2)76 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | ++33 |

| Myocardial Infarction Dimensional Assessment Scale (MIDAS)27 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLMI)77 | Multidimensional | Myocardial infarction | / |

| Cardiac Surgery Symptom Inventory (CSSI)78 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Cardiac Symptom Survey (CSS)79 | Symptoms | CABG | −46 |

| Heart Surgery Symptom Inventory (HSSI)80 | Symptoms | CABG | / |

| Symptoms of Illness Score (SOIS)81 | Symptoms | CABG/valve surgery | / |

| Symptom Inventory82 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery | / |

| Cardiac Symptoms Scale83 | Symptoms | Cardiac surgery/PTCA | / |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) symptom checklist84 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey (MAPMISS)85 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | −46 |

| Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndrome Inventory (SACSI)86 | Symptoms | Acute Coronary Syndrome | −46 |

| Symptom Scale87 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Shortened WHO Rose Angina Questionnaire88 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| WHO Rose angina questionnaire30 | Symptoms | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Angina-related Limitations at Work Questionnaire (ALWQ)89 | Work-related functioning | Ischaemic heart disease | / |

| Congenital heart disease | |||

| ACHD PRO, Adult Congenital Heart Disease—Patient-Reported Outcome90 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | +33 |

| Congenital Heart Disease—TNO/AZL Adult Quality Of Life (CHD-TAAQOL)91 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | −33 |

| PedsQl cardiac module92 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Pediatric Cardiac QOL Inventory93 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Congenital Heart Adolescent and Teenager Questionnaire (CHAT)94 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| ConQol95 | Multidimensional | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Health Behavior Scale—Congenital Heart Disease29 | Behaviour | Congenital heart disease | / |

| Heart failure and transplantation | |||

| Cardiac Health Profile of Congestive Heart Failure (CHPchf)96 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −97 |

| Care-Related Quality of Life survey for Chronic Heart Failure (CaReQol CHF)98 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Assessment Tool (CHAT)99 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100 |

| Chronic Heart Failure-PRO Measure (CHF-PROM)101 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire (CHQ/CHFQ)102 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,100,103 |

| Heart Failure-Functional Status Assessment (HF-FSA)104 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Heart Failure Symptom Checklist105 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)106 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | ++33,97 |

| Knowledge, attitude, self-care practice and HRQoL of Heart Failure patients (KAPQ-HF)107 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Left Ventricular Dysfunction Questionnaire (LVD-36)108 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,100,103 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Inventory e Heart Failure (MDASI-HF)109 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33 |

| Minnesota Living with Heart Failure (MLHF)26 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33,97,100,103 |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Plus-Heart Failure (PROMIS-Plus-HF)110 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | +33 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire in Severe Heart Failure (QLQ-SHF)111 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | −33,97,103 |

| Short version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-12)112 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Traditional Chinese Medicine inquiry (TCM inquiry)113 | Multidimensional | Heart failure | / |

| Heart Transplant Stressor Scale114 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rating Question Form115 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| Rotterdam Quality of Life Questionnaire116 | Multidimensional | Heart transplantation | / |

| LVAD Stressor Scale (modified)117 | Multidimensional | LVAD | / |

| Quality of Life with a Ventricular Assistive Device Questionnaire (QOLVAD)118 | Multidimensional | LVAD | −33 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Awareness Scale (HFSAS)119 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| Heart Failure Somatic Perception Scale (HFSPS)120 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Heart Failure (MSAS-HF)121 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,46 |

| San Diego Heart Failure Questionnaire (SDHFQ)122 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| Symptom Checklist (SCL)123 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Symptom Status Questionnaire—Heart Failure (SSQ-HF)124 | Symptoms | Heart failure | −46 |

| Heart Failure Functional Status Inventory (HFFSI)125 | Symptoms; Functional capabilities | Heart failure | −33,100 |

| European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS)126,127 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128,129 |

| Evaluation Scale for Self-monitoring by Patients with Chronic Heart Failure (ESSMHF)130 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Self-care of Heart Failure Index (SCHFI)131 | Self-care | Heart failure | +128 |

| Spiritual Self-care Practice Scale (SSCPS)132 | Self-care | Heart failure | −128 |

| Valvular diseases | |||

| Heart Valve Disease Impact on daily life (IDCV)133 | Multidimensional | Heart valve disease | −33 |

| Toronto Aortic Stenosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (TASQ)134 | Multidimensional | SAVR/TAVI | −33 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Impact of Syncope on Quality of Life (ISQL)135 | Multidimensional | Syncope | −33 |

| Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ)136 | Multidimensional | Hypotension | +33 |

| Quality of Life Instruments for Chronic Diseases—Hypertension (QLICH-HY)137 | Multidimensional | Hypertension | |

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale138 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Treatment Adherence Questionnaire for Patients with Hypertension (TAQPH)140 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Therapeutic Adherence Scale for Hypertensive Patients (TASHP)141 | Medication adherence | Hypertension | −139 |

| Hypertension Self-Care Profile (HBP SCP)142 | Self-care | Hypertension | / |

AF, Atrial Fibrillation; CABG, Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; DS, domain-specific; ICD, Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator; LVAD, Left Ventricular Assist Device; PTCA, Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty; SC, Single construct; SAVR, Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement; TAVI, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Level of support; /, psychometric properties not evaluated any systematic review; −, the cited systematic review indicated that none or only some of the psychometric properties of this instrument have met COSMIN standards; +, systematic review indicated support for most psychometric properties; ++, systematic review indicated support for all psychometric properties.

In 2012, the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) was launched. ICHOM aims to develop condition-specific standard outcome sets to support the assessment of ‘value-based care’. The ICHOM outcome sets comprise clinical and patient-reported outcomes, and are developed by working parties consisting of clinicians and patient representatives. To date, standard outcome sets for hypertension management in low- and middle-income countries,146 atrial fibrillation,147 congenital heart disease,148 coronary heart disease,149 and heart failure150 and have been developed.

Another organization that develops and inventorizes core outcome sets is the COMET initiative (https://www.comet-initiative.org/). COMET is a European Union/Medical Research Council funded organization that supports and publishes resources, such as a handbook on ‘core outcome set’ development and standards for reporting, i.e. the COS-STAR statement.151 Existing ‘core outcome sets’ for different conditions, including heart and circulatory problems, can be found on the COMET website: https://www.comet-initiative.org/studies. It is important to know that COMET comprises outcome sets that are developed for clinical trials, not necessarily for clinical purposes.

How to choose the most appropriate PROM?

Whether for clinical or research purposes, it is important to select PROMs that provide valid and reliable information in an efficient way. Hence, a sound evaluation of the attributes of the PROMs is essential to find high-quality PROMs that match the intended purposes. The initial evaluative systems were developed for HRQoL instruments.21 Later on, systems were developed for evaluating a broader range of PROMs.

One such system is the ‘Evaluating the Measurement of Patient-Reported Outcomes’ (EMPRO) tool.152 The EMPRO tool comprises 39 items that are organized into eight attributes: Conceptual and measurement model (seven items); Reliability (eight items); Validity (six items); Responsiveness (three items); Interpretability (three items); Administration burden (seven items); Alternative modes of administration (two items); and Cross-cultural and linguistic adaptations (three items). Each item can be scored using a 4-point Likert scale.152 An online platform system for the EMPRO has been developed.153

Another evaluation system, which is the most extensive and most widely used, is the ‘COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments’ (COSMIN). COSMIN developed a taxonomy154 and created checklists to assess the methodological quality of individual studies155 and systematic reviews156 of PROMs. The latest COSMIN checklist comprises 116 items over 10 domains: development (35 items); content validity (31 items); structural validity (four items); internal consistency (five items); cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance (four items); reliability (eight items); measurement error (six items); criterion validity (three items); hypothesis testing for construct validity (seven items); and responsiveness (13 items).156 Items are scored on a 4-point rating system. Whereas COSMIN provides in-depth information on the measurement properties (validity, reliability, and responsiveness), EMPRO gives a broader perspective on the PROM by also assessing the modes and burden of administration of the questionnaire.

In general, it is advised to use a combination of generic and disease-specific instruments to include the advantages of both. When choosing PROMs, patient representatives should be involved (see section on Patient Perspective). It is also important to be aware that some PROMs or specific questions might pose ethical issues when used in research. For instance, it should not remain unnoticed until the end of data collection if a patient reports major depression associated with suicidal ideas. Extreme scores on questionnaires, additional information provided by a patient, or discussions between a patient and research personnel can provide critical information, which is called PRO Alerts.157 A clear strategy is needed on what to do when PRO Alerts occur.157 Recently, PRO ethical guidelines have been developed.158 These guidelines include 14 ethical recommendations to be considered when PROs are assessed in clinical research.158 A final aspect to bear in mind is the terms and conditions of the use of the selected PROMs. Most PROMs can be used free of charge. However, there are some PROMs with very strict regulations for their use and high licensing fees, which may even change over time.159 In such a case, it is appropriate to check if there are good alternatives that are free of charge.

What if there is no suitable PROM available?

If a relevant PROM for a specific condition or problem does not exist, there are three possible ways to proceed:160 (i) a PROM for a condition that is closely related could be used; (ii) a generic instrument could be used; or (iii) a new PROM could be developed.160 The first two options are suboptimal, but the latter option is time-consuming and requires expertise in instrument development and psychometrics. The development of a PROM comprises different steps, such as choosing a conceptual/theoretical framework, generating items, scale formation, testing face validity, and extensive psychometric testing.161 The process of development and psychometric evaluation needs to be thoroughly described.162 When a PROM for a related condition is to be used, it is important that the use of the instrument is evaluated by cognitive interviews with patients having the specific disease to assess its relevance and comprehensiveness.

The patient perspective on PROs

The ESC Patient Forum has been included in the development of this position paper from its inception, and its members were widely consulted and more specifically represented (RM, DF). In a focus group session on 6 October 2020 Forum members expressed broad support for the development and use of PROs in research and clinical practice. They expressed how PROs can facilitate a more holistic evaluation of how various cardiac treatments and procedures impact them as an individual, including mental and physical aspects. Where treatment side effects include fatigue or mood disturbance, these should be explained and patient preferences ought to be taken into consideration. Patient Forum members were keen to emphasize that life-prolonging treatment is often not what an individual patient or their families will wish for—rather, most people want to optimize their quality of life. Patients also recognize heart disease as a chronic condition and want PROs to be regularly updated as time progresses, rather than being regarded as a static endpoint.

Patients believe PROs can serve as an aid to shared decision-making, and their application may tilt the balance in favour of an enhanced focus on patient-centred decision-making. Indeed, patients consider PROs to be the appropriate complement to more clinically focused assessments. The introduction of ePROs and real-time data collection is viewed with interest, though a greater consideration of how they might be integrated into clinical practice is needed. Even greater deliberation is needed when PROs are being considered for the remuneration of healthcare providers.

It is paramount that PROs should capture what matters to patients, and therefore meaningful involvement of patients at all stages of their development is required. The results from PROs obtained in a clinic or for research purposes should be used as a prompt to initiate communication with the patients, especially when the scores deviate from the normal range or from patients’ previous responses. They can also support adherence by integrating feedback from the PRO to facilitate shared decision-making, particularly as patients’ circumstances and choices change over time. Issues such as fatigue can have a much more dramatic impact for patients than a score conveys, with the statement ‘Quality of life is My judgement, not yours’ echoing strongly from this feedback.

PROs in routine clinical care

When used in clinical practice, PROs have the potential to capture patients’ symptoms, functioning, and individual health goals in a quantifiable way, that can be used as part of the dialogue between patients and clinicians concerning diagnostic and treatment decisions.163 This shared decision-making is a critical element of person-centred care.164 Experience with routine assessment of PROs is built up in different clinical areas, such as cancer,165,166 rheumatic diseases,167,168 and orthopaedics.169,170 Within cardiology, there is growing interest from clinicians and patients, but the use of PROs in real-life clinical practice remains sparsely tested or implemented171 and clinicians see several barriers.172

The use of PROs in clinical practice can improve communication with patients and families, collaboration among healthcare professionals, monitoring of disease progression, and evaluation of treatment outcomes (Figure 3). Indeed, PROs can inform healthcare professionals to have a better understanding of the perspective of each particular patient, and they improve clinicians’ assessment of the health status of patients.173 PROs assess what matters to patients in a systematic way. In cardiac rehabilitation, PROs are particularly important and seem to be decisive for success as they predict positive outcomes.174 When PROs are assessed cross-sectionally, they can be compared with population benchmarks. It is also interesting and valid to assess PROs in a longitudinal fashion, because it allows the evaluation of within-person evolutions.

Benefits of the use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice.

The use of PROMs in clinical care has been shown to be effective in improving patient management.175 Hence, giving feedback on PROM findings to healthcare professionals can be considered as an intervention. Clinicians who want to implement PRO assessment in their clinical practice can rely on the user’s guide developed by the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL).176 Healthcare providers need to be educated how to interpret a new measure and how the results can be integrated into the processes of care. Indeed, information from PROMs, being routinely collected through smart phones, patient portals, in-clinic kiosks, or tablets, should be integrated into the medical record in a location that is easily accessed by the clinicians (e.g. the page where the vital signs are located). Further, it is important that clinicians discuss the findings with patients.172 Obviously, this all requires time, financial resources, personnel, and digital infrastructures to implement the assessment of PROs successfully.

While the implementation of PROs in clinical care is aimed mainly at supporting healthcare professionals and healthcare systems by providing data for their clinical decision-making, PROs can also increase patients’ understanding of their health status. In this respect, the use of graphical displays or dashboards is indispensable.177,178 However, one needs to take the graphical literacy of patients and families into consideration.179 Research has shown that visual analogies or infographics are more effective in increasing patients’ understanding of their condition.179

An important feature is that patients should be able to indicate the relative importance of each PRO. As such, they give a weighting to individual items according to what matters to them. Integrating relative importance of items in PROMs is in its infancy, but should be further developed to make PRO assessment more in line with the preferences of individual patients.

PROs in quality monitoring and improvement

There is a growing awareness that PROs have a place in the evaluation of quality of care. This is rooted in the concept of value-based healthcare, which is defined as improving patient-relevant outcomes, relative to the cost per patient for achieving these improvements.180 In this respect, PRO-based performance measures, also known as PRO-based quality indicators, are of key importance.20 PRO-based performance measures entail an aggregation of information collected through PROMs or PREMs.20,21 Data are aggregated for an accountable healthcare entity, such as a ward, a hospital, or a home care agency.21 Performance measures are preferably expressed as ratios. An example is the percentage of patients with depressive feelings, as shown by a score of >9 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ9), who have a follow-up score of <5 at 6 months. The higher the percentage, the better the care that has been provided, because the goals of treatment and care have been reached. Quality indicators that are linked to ESC guidelines that encompass PROMs and PREMs8,181,182 are particularly useful for monitoring the quality of care from patients’ perspectives. It is important that performance measures are risk-adjusted.183

The monitoring of quality of care can also be conducted at regional, national, or international level. For this purpose, quality registries are developed. Quality registries serve as a benchmark to compare healthcare institutions/organizations or to evaluate the effects of quality improvement initiatives. In many national or international registries, the variables related to PROMs and PREMs are not recorded.8,181 Therefore, we call for including patients’ perspective into these existing registries184 with appropriate public funding for relevant PROMs or PREMs that have been validated. Consensus about which PROs to use for each condition has yet to be reached across the national cardiac clinical registries in different countries. The development of data standards for the European Unified Registries for Heart Care Evaluation and Randomized Trials (EuroHeart) are exemplary in this respect. PROs, and more specific HRQoL, are named as key domains that have to be included in the registry.185,186

PROs in clinical trials

The importance of PROs in clinical trials has been recognized since the early 1990s. Indeed, it was found that the adverse event forms that were completed by physicians in two randomized controlled trials on antihypertensive agents captured only 7% of the symptoms that were reported by patients using a structured symptom distress scale.187 Since then, increasingly more clinical trials have used PROs either as primary endpoints of interest, secondary endpoints, or exploratory/tertiary endpoints. In ClinicalTrials.gov, the proportion of trials that included PROs rose from 14% in 2004–07188 to 27% in 2007–13.189 Similarly, the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry showed that 45% of the trials had PROs as trial endpoints in 2005–17.190 This illustrates that the value of PROs in clinical trials has been widely recognized, because the typical endpoints in clinical trials do not always give an accurate reflection of all the risks, benefits, quality of life, and costs for patients.191

In clinical trials, PRO endpoints should be decided a priori, submitted for ethical review, and approved in the trial protocol. For this, existing ‘core outcome sets’ can be relied on. It is advisable to have an expert in psychometrics and clinical interpretations of PROs on the trial committee, and to involve patients in selecting suitable PRO instruments and designing how these instruments will be captured. Regulatory and professional bodies show an emerging consensus when it comes to selecting PROMs for clinical trials.192 Nonetheless, the interpretation of PRO data in clinical trials can be challenging because of a lack of familiarity with their clinical importance.16 Therefore, developers of questionnaires or experts in psychometrics should guide trialists on how to use, analyse and interpret the data obtained by that questionnaire. Recent examples are the specific guidance given on the use of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in clinical trials.15,16 When reporting PRO findings, recommendations for designing, analysing, and reporting, such as SPIRIT-PRO193 and CONSORT-PRO,194 should be followed.

PROs in regulatory affairs

PROs are used for regulatory approval of drugs or medical devices, for example, to support a product label claim. International regulatory agencies have acknowledged that valid, well defined, and rigorously collected measurements of PROs can complement existing measurements of safety and efficacy, as evidence for making regulatory decisions.195

Regarding medicines, fundamental steps that have been proposed toward making drug development a more patient-centred process include engaging patient representatives during the lifecycle of a drug’s development, identifying feasible patient-centred outcomes, and including PROMs in drug labels to support patients and providers when they make therapeutic decisions. The FDA released guidance on the utility of PRO data in 2009, in order to streamline the review of PROMs and associated clinical trial data and to improve methods for considering patients’ perspectives when reviewing medical products.1 In 2019, the FDA specified that a beneficial effect on symptoms or physical function could be the basis for approving a drug to treat heart failure, even if it has no favourable effect on survival or hospitalizations.196 Sponsors are encouraged to consult with the FDA early, to obtain agreement on proposed end-points.196 In 2015, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) stated in a guideline on the investigation of medicines for acute heart failure, that ‘Improvement in quality of life and/or patients’ self-assessed global clinical status, based on validated ordinal measures of response relative to baseline, could be used as secondary endpoint’.197 Further guidance in 2017 stated that PROs should be included as secondary endpoints in chronic heart failure studies, when they should be considered as supportive, but it also acknowledged that, under special circumstances, measures of symptom burden may be acceptable as a primary endpoint.198

The EU Regulation on medical devices (MDR, EU 2017/745, implemented on 26 May 2021 after a transition period) has increased the requirements for clinical evidence concerning new high-risk medical devices.199 Before approval, ‘clinical investigations’ (a term which includes clinical trials) should demonstrate a positive impact on ‘patient-relevant clinical outcomes’ [MDR Article 2 (53) and Article 61].199 After market access, manufacturers have responsibility for continued surveillance, and they are required to submit an annual safety update report.200 In a 2020 document, the FDA gives guidance on the collection, analysis, and integration of patient perspectives in the development, evaluation, and surveillance of medical devices.201 It is argued that information from well-defined and reliable PRO instruments can provide valuable evidence for benefit-risk assessments and can be used in medical device labelling.201 There are no specific European guidance documents on the application of PROs to evaluate medical devices, but the ESC is leading a project (CORE-MD) that will summarize the evidence and recommend to regulators how that could be done.14 As part of the CORE-MD project, it will be scrutinized to what extent minimal clinically important differences (MCID) have been developed and used for regulatory purposes.

PROs for reimbursement and health economics purposes

Following the idea that ‘value lies in the eyes of the patient’,202 it is not surprising to witness increasing use of PROs to inform a broad range of decisions, including those related to coverage and reimbursement, as well as payments to providers.202,203 For instance, there has been a strong endorsement to integrate PROs in a value-based payment reform that dramatically changes the provider reimbursement landscape in the US.10 PROMs and PREMs can be used in reimbursement decisions in pay-for-performance systems, because the quality of care is then also assessed through the lens of patients.204 An example is the Quality and Outcomes Framework in the UK, where primary care practices are financially rewarded for achieving quality standards that include patients’ experiences.205 Indeed, pay-for-performance programs have to take patient experience into account, to avoid disheartening patients and discouraging them from providing feedback on which effective quality improvement must rely.206 However, reimbursements based on PROs should account for adequate risk adjustments. If not, healthcare providers and practices may be penalized for taking care of sicker, more complex, or socially disadvantaged patients, who will have worse PRO scores.

PROs are increasingly recognized as an important focus in health technology assessments (HTAs). HTAs have become a dominant framework for making decisions related to coverage and reimbursement of new medical technologies, and dossiers submitted to HTA agencies often include PRO data, while HRQoL data and utilities (see Figure 2) are often incorporated into cost-effectiveness analyses.

To date, there is still limited evidence of the use of PROs by HTA bodies in Europe and beyond.207,208 The evidence available is focused mainly on understanding the use of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which are mostly based on generic HRQoL measures (i.e. EQ-5D).209 The use of other types of PROs in informing reimbursement decisions (i.e. functional status, symptoms, activities of daily living) has not been sufficiently explored. The inclusion of PROs in reimbursement decisions varies greatly by country and also within a country by payer type, whether national, regional, or local decision-maker.210 This is not a surprise because the extent to which a country relies on the use of HTA in healthcare decision-making is influenced by the underlying culture and values embedded in the institutional context of the country’s particular healthcare system.211

PROs in a digital world