-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Precious Esie, Lisa M Bates, At the intersection of race and immigration: a comprehensive review of depression and related symptoms within the US Black population, Epidemiologic Reviews, Volume 45, Issue 1, 2023, Pages 105–126, https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxad006

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Although the literature on the differences between Black people and White people in terms of differences in major depressive disorder and related self-reported symptoms is robust, less robust is the literature on how these outcomes are patterned within the US Black population and why differences exist. Given increased ethnic diversity of Black Americans due to increases in immigration, continued aggregation may mask differences between Black ethnic-immigrant groups and Black Americans with more distant ancestral ties to Africa (African Americans). The purpose of this narrative review was to comprehensively synthesize the literature on depression and related symptoms within the US Black population across immigration- and ethnicity-related domains and provide a summary of mechanisms proposed to explain variation. Findings revealed substantial variation in the presence of these outcomes within the US Black population by nativity, region of birth, age at immigration, and Caribbean ethnic origin. Racial context and racial socialization were identified as important, promising mechanisms for better understanding variations by region of birth and among those born or socialized in the United States, respectively. Findings warrant data collection efforts and measurement innovation to better account for within-racial differences in outcomes under study. A greater appreciation of the growing ethnic-immigrant diversity within the US Black population may improve understanding of how racism differentially functions as a cause of depression and related symptoms within this group.

Introduction

Across nationally representative studies of diagnostic psychiatric disorders, the prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) is markedly lower among Black Americans relative to White Americans.1,–5 This finding is inconsistent with observed racial patterns in self-reported measures of depressive symptoms and psychological distress.6 Between-racial patterns of MDD are also inconsistent with theories of social stress, the predominant framework linking social status to mental health, positing individuals with disadvantaged social statuses are exposed to more stressors than those of advantaged social statuses, and such stress exposure leads to worse mental health.7,–9 Consequently, numerous investigations have sought to explain this apparent, paradoxical between-racial pattern.6,10,–14 Although the literature on between-group differences between Black people and White people in terms of depression and related self-reported symptoms is robust, fewer investigations have explored potential heterogeneity within the US Black population.

Aggregating the US Black population is standard practice in health research, despite increased ethnic diversity due to increasing numbers of Black immigrant populations. As of 2019, an estimated record 4.6 million Black immigrants live in the United States, nearly double the population since 2000.15 Although Black immigrants in the United States come from several regions, nearly half were born in the Caribbean and 42% were born in sub-Saharan Africa.15 Also as of 2019, 12% of the Black population were foreign-born immigrants, and an additional 9% were second-generation (ie, those with at least 1 foreign-born parent).16 Increasing numbers of both first- and second-generation immigrants signify increasing ethnic diversity within the US Black population. Despite this growing diversity, Black ethnicities, nativity, and immigrant generation status are rarely studied in health research.17,–21 Instead, in both US public discourse and in health research, “African American” is often used interchangeably with Black, yet the former refers to an ethnic group and the latter to a racial category. African American typically refers to Black Americans with distant ancestral ties (ie, more than 3 generations removed) to Africa,22 nearly all being descendants of enslaved Africans forced into the United States. Culturally and historically, African Americans are distinct from the US Black population with more recent immigrant origins.22 Few data sources contain sufficient samples to disaggregate Black respondents. Subsequently, few investigations exist of prevalence patterns in mental health outcomes within the US Black population and causes underlying potential within-racial differences. Studies following an intersectional perspective whereby Black race and immigration are theorized as uniquely contributing to depression risk are limited.

In studies of depression among US Black populations, distinctions between depression-related outcomes and measures are salient. The presence of diagnostic depression outcomes, like MDD, is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and based on the presence of a cluster of symptoms for at least 2 weeks, causing clinically significant distress.23 Measures of self-reported depressive symptoms are conceptually distinct yet overlap with diagnostic depression.24 Scales such as the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) and the Patient Health Questionnaire have been validated as screening tools for diagnostic depression.25,–27 Psychological distress is characterized by symptoms of depressed mood in addition to symptoms of anxiety28; it has also been described as a normal emotional reaction to stressors that does not necessarily rise to the level of disorder.29 Together, measures of depressive symptoms and psychological distress fall short of meeting DSM criteria for depression.6 Although it follows that these self-reported symptom scales ought to be positively correlated with MDD, data have repeatedly shown Black Americans have a lower prevalence of MDD relative to White Americans, yet they have higher levels of both self-reported measures of depressive symptoms and psychological distress across a range of nationally representative studies.6 These discrepant patterns may suggest etiologies of diagnostic depression and related self-reported symptoms (ie, depressive symptoms and psychological distress) vary for Black Americans. A better understanding of how diagnostic depression and these related symptoms are patterned within the US Black population could provide insight into the extent to which etiologies underlying these constructs may vary.

To our knowledge, only 1 review exists characterizing the prevalence of depression within the US Black population across immigration-related domains and identifies potential mechanisms underlying differences.30 The authors cited studies of diagnostic depression that disaggregated by nativity and drew from 1 of 2 large, nationally representative studies: the National Study of American Life (NSAL) or the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). NSAL and NESARC data showed foreign-born Black immigrants generally had a lower prevalence of MDD (both in the past year and during their lifetime) compared with US-born Black Americans. Comparisons within the US-born group were limited to NSAL data, which showed those of recent Caribbean origin had a substantially higher prevalence of MDD compared with African Americans. And although the authors included a discussion of mechanisms that may protect the foreign-born Black immigrant population, there was no discussion of potential mechanisms underlying differences within the US-born Black population.30 A synthesis of prevalence patterns and mechanisms across a wider range of depression outcomes and immigration-related domains, such as region of birth, immigrant generation, or ethnic origin beyond Caribbean, does not exist, to our knowledge.

The present narrative review has 2 objectives. First, we sought to comprehensively synthesize the limited literature on depression and related symptoms within the US Black population, which disaggregates by immigration- and ethnicity-related domains. And second, within the literature captured by this synthesis, we sought to summarize mechanisms proposed to explain any differences in observed prevalence patterns. The present review was not restricted to nationally representative studies, which may provide additional insight into prevalence patterns beyond nativity or Caribbean origin and mechanisms beyond nativity. We focused on adults (aged 18 years or older) and youth (younger than 18 years) separately.

Methods

Search strategy

In October 2021, we comprehensively searched for peer-reviewed studies in the PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science databases without imposing date restrictions, and used the following search string across all fields: (“Black” OR “Africa*” OR “Caribbean”) AND (“Immigra*” OR “Migrant” OR “Nativity” OR “Foreign”) AND (“Depress*” OR “Distress” OR “Mood disorder”). The search was limited to studies written in English. Studies were included in the narrative review if they provided quantitative data on the prevalence of diagnostic measures of depression (MDD, major depressive episode, dysthymia) or related self-reported symptoms (eg, depressive symptoms, psychological distress) among Black subgroups in the United States disaggregated by a domain related to ethnic or immigrant origin (eg, Caribbean ethnicity, nativity, immigrant generation). Comparative studies of Black people and White people were not eligible unless they further disaggregated race by domains of interest.

Studies were excluded for the following reasons: data on major depression or related symptoms were not provided, data were not disaggregated by domains of interest, or the study sample was from a non-Black or non-US population. Unpublished manuscripts, conference abstracts, case reports, and studies without quantitative data were ineligible. Considering the limited extant literature, we did not attempt to perform a systematic review with a formal quality assessment process.

We deposited search results into the reference management program, Endnote (Clarivate), where duplicate records were deleted. Then, we screened titles and abstracts of the remaining records to exclude irrelevant studies. Next, we retrieved full text of articles for screening. Finally, we screened reference lists of retained articles to identify additional articles. From the final set of articles, we extracted study characteristics, depression measure characteristics, subgroup characteristics, and a summary of findings. In addition, we scanned the introduction and discussion sections of included articles to identify proposed mechanisms underlying reported differences within the US Black population and to determine if the basis of the proposed mechanism was a priori or a posteriori. A mechanism was classified as a priori if it was a clear hypothesis of a given study, raised in the introduction section, regardless of whether it was formally tested. A mechanism was classified as a posteriori if it was clearly raised only in the discussion section.

Results

Study selection

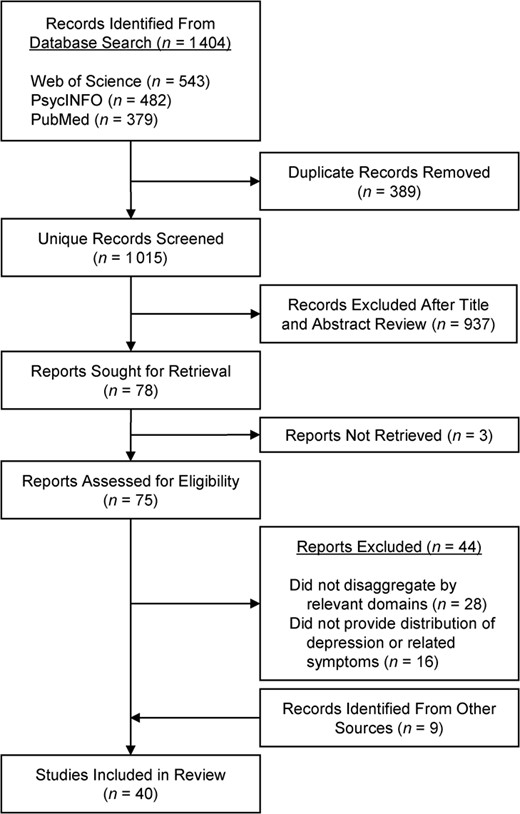

Figure 1 summarizes the study selection. The initial search yielded 1 404 articles across 3 databases; from the original total, 389 duplicates were removed. Next, 1 015 titles and abstracts were screened, and 937 additional records were removed because they were deemed ineligible. The full text of the remaining 78 records was sought for retrieval; of these, 3 were unavailable. The full text was assessed on the remaining 75 articles and 44 were excluded because either the authors did not disaggregate by the domains under study (n = 28) or they did not provide the distribution of depression or related symptoms (n = 16). Nine additional records were identified from other sources (n = 8 from reference lists and 1 from expert consultation). In total, 40 studies were included in the review.

Characteristics of studies included

Table 1 provides characteristics of studies included in the review. Of the 40 studies included, 33 used adult samples and 7 used youth samples. Additionally, 31 drew from national samples of the general (ie, noninstitutionalized) US population (n = 25 adults and 6 youth). Among adults, these national surveys were the first wave of the NESARC, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), mothers interviewed in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Birth Cohort, and the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES). The CPES combined data from 3 sister studies conducted during the same period (2001–2003): the National Comorbidity Survey (Replication) (NCS-R), the National Latino and Asian American Study, and the NSAL. The NSAL is the largest study to date of mental health of Black people, and most studies of adults (n = 20 of 33, including those labeled as CPES) drew from it. Estimates within the US Black population derived from the CPES combined NSAL and NCS-R data. Among youth, all studies except 1 were nationally representative (n = 6 of 7); these national surveys were the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, the adolescent supplement of the NCS-R, and the adolescent supplement of the NSAL (NSAL-A).

Characteristics of studies on depression and related symptoms within the US Black population disaggregating by immigration- and ethnicity-related domains (N = 40).

| Study characteristic . | Overall (N = 40) . | Adults (n = 33) . | Youth (n = 7) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | |||

| Nationally representative | 31 | 25 | 6 |

| CPES/NSAL | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| ECLS-B | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| NESARC | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| NHIS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Add Health | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NCS-A | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NSAL-A | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Not nationally representative | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| Depression measures | |||

| Diagnostic depression | 18 | 15 | 3 |

| MDDa | 13 | 11 | 2 |

| MDE or dysthymia | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Mood disorderb | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Self-reported symptoms onlyc | 22 | 18 | 4 |

| Subgroups | |||

| US nativity | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Region of birth | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Age at immigration | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Immigrant generation | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Parent nativity | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Caribbean ethnic origind | 25 | 21 | 4 |

| Study characteristic . | Overall (N = 40) . | Adults (n = 33) . | Youth (n = 7) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | |||

| Nationally representative | 31 | 25 | 6 |

| CPES/NSAL | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| ECLS-B | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| NESARC | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| NHIS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Add Health | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NCS-A | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NSAL-A | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Not nationally representative | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| Depression measures | |||

| Diagnostic depression | 18 | 15 | 3 |

| MDDa | 13 | 11 | 2 |

| MDE or dysthymia | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Mood disorderb | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Self-reported symptoms onlyc | 22 | 18 | 4 |

| Subgroups | |||

| US nativity | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Region of birth | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Age at immigration | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Immigrant generation | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Parent nativity | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Caribbean ethnic origind | 25 | 21 | 4 |

Abbreviations: Add Health, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health; CPES, Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiological Studies; ECLS-B, Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey–Birth Cohort; MDD, major depressive disorder; MDE, major depressive episode; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NSAL, National Survey of American Life; NSAL-A, National Survey of American Life–Adolescent Supplement.

a Refers to all studies with a separate measure of MDD. Studies that measured MDD and other depression measures separately are included.

b A broader measure that includes MDD.

c Refers to measures of depressive symptoms or psychological distress.

d Caribbean ethnic origin either alone or in combination with nativity.

Characteristics of studies on depression and related symptoms within the US Black population disaggregating by immigration- and ethnicity-related domains (N = 40).

| Study characteristic . | Overall (N = 40) . | Adults (n = 33) . | Youth (n = 7) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | |||

| Nationally representative | 31 | 25 | 6 |

| CPES/NSAL | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| ECLS-B | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| NESARC | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| NHIS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Add Health | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NCS-A | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NSAL-A | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Not nationally representative | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| Depression measures | |||

| Diagnostic depression | 18 | 15 | 3 |

| MDDa | 13 | 11 | 2 |

| MDE or dysthymia | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Mood disorderb | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Self-reported symptoms onlyc | 22 | 18 | 4 |

| Subgroups | |||

| US nativity | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Region of birth | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Age at immigration | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Immigrant generation | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Parent nativity | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Caribbean ethnic origind | 25 | 21 | 4 |

| Study characteristic . | Overall (N = 40) . | Adults (n = 33) . | Youth (n = 7) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | |||

| Nationally representative | 31 | 25 | 6 |

| CPES/NSAL | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| ECLS-B | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| NESARC | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| NHIS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Add Health | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NCS-A | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NSAL-A | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Not nationally representative | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| Depression measures | |||

| Diagnostic depression | 18 | 15 | 3 |

| MDDa | 13 | 11 | 2 |

| MDE or dysthymia | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Mood disorderb | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Self-reported symptoms onlyc | 22 | 18 | 4 |

| Subgroups | |||

| US nativity | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Region of birth | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Age at immigration | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Immigrant generation | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Parent nativity | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Caribbean ethnic origind | 25 | 21 | 4 |

Abbreviations: Add Health, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health; CPES, Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiological Studies; ECLS-B, Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey–Birth Cohort; MDD, major depressive disorder; MDE, major depressive episode; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NSAL, National Survey of American Life; NSAL-A, National Survey of American Life–Adolescent Supplement.

a Refers to all studies with a separate measure of MDD. Studies that measured MDD and other depression measures separately are included.

b A broader measure that includes MDD.

c Refers to measures of depressive symptoms or psychological distress.

d Caribbean ethnic origin either alone or in combination with nativity.

Of the 33 studies using adult samples, 15 used fully structured, lay-administered diagnostic interviews to measure Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Revision (DSM-IV) outcomes; 11 included a measure of MDD alone (lifetime or past-year recall), 2 included MDD in a measure of mood disorders broadly (lifetime recall), and 2 used a measure of major depressive episode or dysthymia (lifetime or past-year recall). All studies using DSM-IV criteria drew from either the NESARC or the CPES (including NSAL studies). The remaining 22 studies of adults used instruments capturing self-reported depressive symptoms or psychological distress, such as the CES-D and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. Of the 7 studies using youth samples, 3 used structured interviews to measure lifetime or past-year MDD according to DSM-IV criteria. Of these 3 studies, 2 measured MDD alone and used the NSAL-A, whereas 1 included MDD in a measure of mood disorders broadly using the adolescent supplement of the NCS-R. The remaining 4 studies used instruments capturing depressive symptoms (eg, CES-D).

Among studies estimating diagnostic measures of depression, data were collected from surveys conducted between 2001 and 2003. Among studies estimating levels of self-reported depressive symptoms, studies took place between 2001 and 2015. Last, studies estimating psychological distress collected data between 1998 and 2018.

Subgroups identified

Subgroups identified in studies using adult samples were defined by US nativity alone (US-born, foreign-born; n = 8), region of birth (ie, US-born, Caribbean-born, African-born; n = 3), or age at immigration (<13 years, ≥13 years, or US-born; n = 1), and most studies characterized subgroups by Caribbean origin (Caribbean, non-Caribbean; n = 21), with some additionally disaggregating Caribbean immigrants by nativity (foreign-born Caribbean, US-born Caribbean, non-Caribbean). All studies disaggregating by Caribbean origin drew from the NSAL (including the broader CPES) or NESARC.

Among youth samples, the subgroups identified were defined by immigrant generation (first, second, third or more [hereafter referred to as “third+”]; n = 2), parent nativity (at least 1 foreign-born parent, 2 US-born parents; n = 1), and Caribbean origin (n = 3). Of the 3 studies disaggregating by Caribbean origin, all drew from the NSAL-A, and 1 further disaggregated by parent nativity (non-Caribbean, Caribbean with at least 1 foreign-born parent, Caribbean with 2 US-born parents).

Depression and related symptoms among Black adults

The following results pertain to the 33 included studies using samples of Black adults (Table 2).

Findings from studies on depression and related symptoms within the US Black population disaggregating by immigration- and ethnicity-related domains among adults (n = 33 studies).

| First author, yearreference no. . | Data source (collection period) . | Depression measure . | Recall . | Instrument . | Cutoff score or description . | Black subgroups (no.) . | Non-Black subgroups . | Summary of findings . | Proposed mechanismsa . | Mechanism reasoninga . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain: Nativity and region of birth (n = 11 studies) | ||||||||||

| Dey, 200631 | NHIS (1998–2003) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥13 | US-born (NR);foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: US-born, 3.3%; foreign-born, 1.9% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Doe, 201732 | Community sample of mothers, New York City, NY (2015) | Probable postpartum depression | NR | EPDS | ≥9 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | US-born Latinx, foreign-born Latinx | Prevalence: US-born, 22.81%; foreign-born, 23.81% | None | N/A |

| Donovan, 201333 | Multisite study of college students (2008–2009) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 20 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 1–100 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 896 | Asian, Latinx, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Mean (NS): US-born, 51.81; foreign-born, 49.81 | None | N/A |

| Elo, 201038 | Community sample of pregnant women, Philadelphia, PA (1999–2004) | Probable depression | NR | CES-D | ≥23 | US-born (2816); foreign-born African (106); foreign-born Caribbean (179) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 21.7%; foreign-born, 25.6%; foreign-born African, 22.6%; foreign-born Caribbean, 27.4%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 1.52 (NS); foreign-born Caribbean, 1.61 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Henning-Smith, 201334 | Random sample of enrollees in Minnesota Health Care Programs (2008) | Probable depression | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | ≥3 | US-born (242); Somali-born (288) | White | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 31.6%; Somali-born: 9.1% | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Huang, 200735 | ELCS-B; mothers (2001–2002) | Depressive symptoms | NR | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Categorical; severe, ≥15; moderate, 10–14; mild, 5–9; no depression, 0–4 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity, when possible | Severe depression prevalence: US-born, 10.7%; foreign-born, 4.9%. Moderate depression prevalence: US-born, 15.2%; foreign-born, 16.9% Mild depression prevalence: US-born, 30.6%; foreign-born, 20.7% | None | N/A |

| Kreiger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston (2003–2004) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥ 13 | US-born (193); foreign-born (275) | None | Prevalence: US-born: 14.2%; foreign-born: 16.2% | None | N/A |

| Krieger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston, MA (2003–2004) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–24 | US-born(193); foreign-born (275) | None | Mean US-born, 6.6; foreign-born, 8.3 | None | N/A |

| Marquez-Velarde, 202139 | NHIS (2000–2018) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Categorical; severe: ≥13 moderate: 5–12; low or no distress: 0–4 | US-born (216 538); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean (14 725); foreign-born South American (1386); foreign-born European (857); foreign-born African (7537) | None | Moderate to severe distress prevalence: US-born, 14.3%; foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 14.9%; foreign-born South American, 9.1%; foreign-born European, 15.6%; foreign-born African, 13.2%. Moderate to severe distress ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 0.795 (P < 0.05); foreign-born South American, 0.499 (P < 0.05); foreign-born European, 1.034 (NS); foreign-born African: 0.810 (P < 0.05) | Racial context hypothesis | A priori |

| Miranda, 200540 | Community sample of low-income mothers; Washington, DC, Maryland, Virginia area (1997–2001) | Probable depression | Past month | PRIME-MD | NR | US-born (7965); foreign-born African (913); foreign-born Caribbean (273) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 10.5%; foreign-born African, 3.9%; foreign-born Caribbean, 4.8% Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 0.34 (P < 0.05); foreign-born Caribbean, 0.42 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Schwarz, 201237 | New York City Community Health Survey; women only (2002, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008) | Probable depression | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥7 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 7655 | White, Latinx; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence (NS): US-born, 24.2%; foreign-born: 23.6%. Adjusted OR: US-born (ref); foreign-born, 1.01 (NS) | None | N/A |

| Zick, 201941 | Community sample of women, Utah (2012–2015) | Depressive symptoms | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | Continuous; range, 0–6 | US-born (96); foreign-born African (79) | Latina, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and White | Mean US-born, 1.04; foreign-born African, 2.02 | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Domain: Age at immigration (n = 1 study) | ||||||||||

| Breslau, 200942 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD, dysthymia or bipolar disorder | Lifetime | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | US-born (7541); immigrated at <13 years of age (153); immigrated at ≥13 years of age (613) | Latinx: Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Central/South America; White: Western Europe, Eastern Europe. Each group was additionally disaggregated by age at immigration. | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 16.28%; immigrated at <13 years of age, 12.67%; immigrated ≥13 years of age, 7.72%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); immigrated at <13 years of age: 0.98 (NS); immigrated at ≥13 years of age, 0.43 (P < 0.05) | Childhood socialization in the United States | A priori |

| Domain: Caribbean ethnic origin (n = 21 studies) | ||||||||||

| Anglin, 201443 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3464); US-born Caribbean (373); foreign-born Caribbean (1114) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 5.3%; US-born Caribbean, 13.4%; foreign-born Caribbean, 5.6% | Subgroup variation in main effects | A priori |

| Assari, 201444 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1621) | None | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 5.4%; Caribbean, 7.8% | None | N/A |

| Boyd, 201145 | NSAL; mothers (2001–2003) | MDE | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (2019); Caribbean (799) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 14.51%; Caribbean, 15.22% | None | N/A |

| Boyd, 201145 | NSAL; mothers (2001–2003) | MDE | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (2019); Caribbean (799) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean: 7.95%; Caribbean: 6.77% | None | N/A |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3434); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher MDD prevalence relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDE | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3433); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher MDE prevalence relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3578); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher mean CES-D score relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Doyle, 201247 | NSAL; fathers (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (1254); US-born Caribbean (175); foreign-born Caribbean (458) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05); non-Caribbean: 6.9%; US-born Caribbean, 20.2%; foreign-born Caribbean: 8.3% | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Erving, 202148 | NSAL; adults aged ≥40 years (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (1616); Caribbean (601) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.17; Caribbean: 5.90 | Noneb | N/A |

| Gibbs, 201363 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD | Lifetime | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (7529); Caribbean (469) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 9.10%; Caribbean, 4.27%. Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 0.57 (P < 0.05) | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Gibbs, 201363 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD | Past year | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (7529); Caribbean (469) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 4.58%; Caribbean, 2.22% Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 0.58 (NS) | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| González, 201049 | CPES (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Foreign-born Caribbean (66.6%); US-born Caribbean (33.4%); Caribbean total = 1476. Foreign-born non-Caribbean (2.3%); US-born non-Caribbean (97.1%); non-Caribbean total = 4249 | Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence Foreign-born Caribbean, 9.1%; US-born Caribbean, 24.1%; foreign-born non-Caribbean, 13.4%; US-born non-Caribbean, 13.1% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| González, 201049 | CPES (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Foreign-born Caribbean (66.6%); US-born Caribbean (33.4%); Caribbean total = 1476. Foreign-born non-Caribbean (2.3%); US-born non-Caribbean (97.1%); non-Caribbean total = 4249 | Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: foreign-born Caribbean, 4.8%; US-born Caribbean, 13.4%; foreign-born non-Caribbean, 8.0%; US-born non-Caribbean, 7.2% | Healthy immigrant effect c | A posteriori |

| Griffith, 201150 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3570); US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 6.70; US-born Caribbean, 7.45; foreign-born Caribbean, 5.81 | Nonee | N/A |

| Head, 201751 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–4 | Non-Caribbean (3414); US-born Caribbean (446); foreign-born Caribbean (1114) | None | Mean (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean, 0.521; US-born Caribbean, 0.635; foreign-born Caribbean, 0.417 | Noneb | N/A |

| Ida, 201252 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (2953); Caribbean (1140) | None | Mean (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean, 6.60; Caribbean: 6.25 | Noneb | N/A |

| Jimenez, 201053 | CPES; adults aged ≥60 years (2001–2003) | MDE, dysthymia | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (671); Caribbean (163); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (34); foreign-born Caribbean (159) | White, Latinx, Asian; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 5.4%; Caribbean, 8.1%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born, 13.6%; foreign-born, 5.7% | None | N/A |

| Jimenez, 201053 | CPES; adults aged ≥60 years (2001–2003) | MDE, dysthymia | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (671); Caribbean (163); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (34); foreign-born Caribbean (159) | White, Latinx, Asian Each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity. | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 2.3%; Caribbean, 4.6%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born, 9.2%; foreign-born, 2.6% | None | N/A |

| Jones, 202054 | NSAL; women only (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Nativity and Caribbean ethnicity: US-born non-Caribbean (2242); US-born Caribbean (264); foreign-born Caribbean (705) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 14.4%; US-born Caribbean, 22.6%; oreign-born Caribbean, 11.2% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Jones, 202054 | NSAL; women only (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Nativity and Caribbean ethnicity: US-born non-Caribbean (2242); US-born Caribbean (264); foreign-born Caribbean (705) | None | Prevalence: US-born non-Caribbean, 8.2%; US-born Caribbean, 7.5%; foreign-born Caribbean, 7.0% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Lincoln, 200755 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3361); Caribbean (1554) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 6.78; Caribbean: 6.07 | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Mays, 201856 | NSAL; men only (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | US-born non-Caribbean (1222); US-born Caribbean (176); foreign-born Caribbean (461) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 8.8%; US-born Caribbean, 21.1%; foreign-born Caribbean, 8.9% | None | N/A |

| Mays, 201856 | NSAL; men only (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | US-born non-Caribbean (1222); US-born Caribbean (176); foreign-born Caribbean (461) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 4.6%; US-born Caribbean, 16.4%; foreign-born Caribbean, 4.9% | None | N/A |

| Mereish, 201657 | NSAL; men (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–3 | Non-Caribbean (1201); Caribbean (545) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 0.51; Caribbean, 0.49 | Noned | N/A |

| Molina, 201658 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1418) | None | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.76%; Caribbean, 6.70%; Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 1.58 (NS). Effect modification: for Caribbean immigrants, but not African Americans, internalized racism was associated with decreased odds of MDD. | Noned | N/A |

| Taylor, 202062 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (11) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.70; Caribbean, 6.40 | None | N/A |

| Taylor, 202062 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–24 | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (11) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 3.81; Caribbean: 3.52 | None | N/A |

| Williams, 200759 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1621); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean: 10.4%; Caribbean: 12.9%; within Caribbean ethnicity (P < 0.05) US-born Caribbean, 19.8%; foreign-born Caribbean, 8.9% | None | N/A |

| Williams, 200759 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570) Caribbean (1621); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean, 5.9%; Caribbean, 7.2%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born Caribbean, 10.9%; foreign-born Caribbean, 2.0% | None | N/A |

| Woodward, 201261 | CPES; adults aged ≥55 years (2001–2003) | MDD or dysthymia | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean ≥55 years old (780); Caribbean ≥55 years old (262) | White, Latinx, Asian | Prevalence: non-Caribbean ≥55 years old, 5.4%; Caribbean aged ≥55 years, 11.2%. Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean aged ≥55 years (ref); Caribbean aged ≥55 years, 3.17 (P < 0.05) | Measurement error, religiosity | A posteriori |

| Woodward, 201360 | NSAL; adults aged ≥50 years (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years (1074); Caribbean aged ≥50 years (415) | White | Prevalence (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 8.8%; Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 11.2% | None | N/A |

| Woodward, 201360 | NSAL; adults aged ≥50 years (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years (1074); Caribbean aged ≥50 years (415) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 4.0%; Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 8.1% | None | N/A |

| First author, yearreference no. . | Data source (collection period) . | Depression measure . | Recall . | Instrument . | Cutoff score or description . | Black subgroups (no.) . | Non-Black subgroups . | Summary of findings . | Proposed mechanismsa . | Mechanism reasoninga . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain: Nativity and region of birth (n = 11 studies) | ||||||||||

| Dey, 200631 | NHIS (1998–2003) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥13 | US-born (NR);foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: US-born, 3.3%; foreign-born, 1.9% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Doe, 201732 | Community sample of mothers, New York City, NY (2015) | Probable postpartum depression | NR | EPDS | ≥9 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | US-born Latinx, foreign-born Latinx | Prevalence: US-born, 22.81%; foreign-born, 23.81% | None | N/A |

| Donovan, 201333 | Multisite study of college students (2008–2009) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 20 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 1–100 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 896 | Asian, Latinx, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Mean (NS): US-born, 51.81; foreign-born, 49.81 | None | N/A |

| Elo, 201038 | Community sample of pregnant women, Philadelphia, PA (1999–2004) | Probable depression | NR | CES-D | ≥23 | US-born (2816); foreign-born African (106); foreign-born Caribbean (179) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 21.7%; foreign-born, 25.6%; foreign-born African, 22.6%; foreign-born Caribbean, 27.4%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 1.52 (NS); foreign-born Caribbean, 1.61 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Henning-Smith, 201334 | Random sample of enrollees in Minnesota Health Care Programs (2008) | Probable depression | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | ≥3 | US-born (242); Somali-born (288) | White | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 31.6%; Somali-born: 9.1% | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Huang, 200735 | ELCS-B; mothers (2001–2002) | Depressive symptoms | NR | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Categorical; severe, ≥15; moderate, 10–14; mild, 5–9; no depression, 0–4 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity, when possible | Severe depression prevalence: US-born, 10.7%; foreign-born, 4.9%. Moderate depression prevalence: US-born, 15.2%; foreign-born, 16.9% Mild depression prevalence: US-born, 30.6%; foreign-born, 20.7% | None | N/A |

| Kreiger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston (2003–2004) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥ 13 | US-born (193); foreign-born (275) | None | Prevalence: US-born: 14.2%; foreign-born: 16.2% | None | N/A |

| Krieger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston, MA (2003–2004) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–24 | US-born(193); foreign-born (275) | None | Mean US-born, 6.6; foreign-born, 8.3 | None | N/A |

| Marquez-Velarde, 202139 | NHIS (2000–2018) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Categorical; severe: ≥13 moderate: 5–12; low or no distress: 0–4 | US-born (216 538); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean (14 725); foreign-born South American (1386); foreign-born European (857); foreign-born African (7537) | None | Moderate to severe distress prevalence: US-born, 14.3%; foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 14.9%; foreign-born South American, 9.1%; foreign-born European, 15.6%; foreign-born African, 13.2%. Moderate to severe distress ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 0.795 (P < 0.05); foreign-born South American, 0.499 (P < 0.05); foreign-born European, 1.034 (NS); foreign-born African: 0.810 (P < 0.05) | Racial context hypothesis | A priori |

| Miranda, 200540 | Community sample of low-income mothers; Washington, DC, Maryland, Virginia area (1997–2001) | Probable depression | Past month | PRIME-MD | NR | US-born (7965); foreign-born African (913); foreign-born Caribbean (273) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 10.5%; foreign-born African, 3.9%; foreign-born Caribbean, 4.8% Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 0.34 (P < 0.05); foreign-born Caribbean, 0.42 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Schwarz, 201237 | New York City Community Health Survey; women only (2002, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008) | Probable depression | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥7 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 7655 | White, Latinx; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence (NS): US-born, 24.2%; foreign-born: 23.6%. Adjusted OR: US-born (ref); foreign-born, 1.01 (NS) | None | N/A |

| Zick, 201941 | Community sample of women, Utah (2012–2015) | Depressive symptoms | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | Continuous; range, 0–6 | US-born (96); foreign-born African (79) | Latina, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and White | Mean US-born, 1.04; foreign-born African, 2.02 | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Domain: Age at immigration (n = 1 study) | ||||||||||

| Breslau, 200942 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD, dysthymia or bipolar disorder | Lifetime | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | US-born (7541); immigrated at <13 years of age (153); immigrated at ≥13 years of age (613) | Latinx: Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Central/South America; White: Western Europe, Eastern Europe. Each group was additionally disaggregated by age at immigration. | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 16.28%; immigrated at <13 years of age, 12.67%; immigrated ≥13 years of age, 7.72%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); immigrated at <13 years of age: 0.98 (NS); immigrated at ≥13 years of age, 0.43 (P < 0.05) | Childhood socialization in the United States | A priori |

| Domain: Caribbean ethnic origin (n = 21 studies) | ||||||||||

| Anglin, 201443 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3464); US-born Caribbean (373); foreign-born Caribbean (1114) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 5.3%; US-born Caribbean, 13.4%; foreign-born Caribbean, 5.6% | Subgroup variation in main effects | A priori |

| Assari, 201444 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1621) | None | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 5.4%; Caribbean, 7.8% | None | N/A |

| Boyd, 201145 | NSAL; mothers (2001–2003) | MDE | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (2019); Caribbean (799) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 14.51%; Caribbean, 15.22% | None | N/A |

| Boyd, 201145 | NSAL; mothers (2001–2003) | MDE | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (2019); Caribbean (799) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean: 7.95%; Caribbean: 6.77% | None | N/A |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3434); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher MDD prevalence relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDE | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3433); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher MDE prevalence relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3578); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher mean CES-D score relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Doyle, 201247 | NSAL; fathers (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (1254); US-born Caribbean (175); foreign-born Caribbean (458) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05); non-Caribbean: 6.9%; US-born Caribbean, 20.2%; foreign-born Caribbean: 8.3% | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Erving, 202148 | NSAL; adults aged ≥40 years (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (1616); Caribbean (601) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.17; Caribbean: 5.90 | Noneb | N/A |

| Gibbs, 201363 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD | Lifetime | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (7529); Caribbean (469) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 9.10%; Caribbean, 4.27%. Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 0.57 (P < 0.05) | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Gibbs, 201363 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD | Past year | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (7529); Caribbean (469) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 4.58%; Caribbean, 2.22% Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 0.58 (NS) | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| González, 201049 | CPES (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Foreign-born Caribbean (66.6%); US-born Caribbean (33.4%); Caribbean total = 1476. Foreign-born non-Caribbean (2.3%); US-born non-Caribbean (97.1%); non-Caribbean total = 4249 | Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence Foreign-born Caribbean, 9.1%; US-born Caribbean, 24.1%; foreign-born non-Caribbean, 13.4%; US-born non-Caribbean, 13.1% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| González, 201049 | CPES (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Foreign-born Caribbean (66.6%); US-born Caribbean (33.4%); Caribbean total = 1476. Foreign-born non-Caribbean (2.3%); US-born non-Caribbean (97.1%); non-Caribbean total = 4249 | Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: foreign-born Caribbean, 4.8%; US-born Caribbean, 13.4%; foreign-born non-Caribbean, 8.0%; US-born non-Caribbean, 7.2% | Healthy immigrant effect c | A posteriori |

| Griffith, 201150 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3570); US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 6.70; US-born Caribbean, 7.45; foreign-born Caribbean, 5.81 | Nonee | N/A |

| Head, 201751 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–4 | Non-Caribbean (3414); US-born Caribbean (446); foreign-born Caribbean (1114) | None | Mean (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean, 0.521; US-born Caribbean, 0.635; foreign-born Caribbean, 0.417 | Noneb | N/A |

| Ida, 201252 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (2953); Caribbean (1140) | None | Mean (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean, 6.60; Caribbean: 6.25 | Noneb | N/A |

| Jimenez, 201053 | CPES; adults aged ≥60 years (2001–2003) | MDE, dysthymia | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (671); Caribbean (163); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (34); foreign-born Caribbean (159) | White, Latinx, Asian; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 5.4%; Caribbean, 8.1%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born, 13.6%; foreign-born, 5.7% | None | N/A |

| Jimenez, 201053 | CPES; adults aged ≥60 years (2001–2003) | MDE, dysthymia | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (671); Caribbean (163); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (34); foreign-born Caribbean (159) | White, Latinx, Asian Each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity. | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 2.3%; Caribbean, 4.6%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born, 9.2%; foreign-born, 2.6% | None | N/A |

| Jones, 202054 | NSAL; women only (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Nativity and Caribbean ethnicity: US-born non-Caribbean (2242); US-born Caribbean (264); foreign-born Caribbean (705) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 14.4%; US-born Caribbean, 22.6%; oreign-born Caribbean, 11.2% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Jones, 202054 | NSAL; women only (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Nativity and Caribbean ethnicity: US-born non-Caribbean (2242); US-born Caribbean (264); foreign-born Caribbean (705) | None | Prevalence: US-born non-Caribbean, 8.2%; US-born Caribbean, 7.5%; foreign-born Caribbean, 7.0% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Lincoln, 200755 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3361); Caribbean (1554) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 6.78; Caribbean: 6.07 | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Mays, 201856 | NSAL; men only (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | US-born non-Caribbean (1222); US-born Caribbean (176); foreign-born Caribbean (461) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 8.8%; US-born Caribbean, 21.1%; foreign-born Caribbean, 8.9% | None | N/A |

| Mays, 201856 | NSAL; men only (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | US-born non-Caribbean (1222); US-born Caribbean (176); foreign-born Caribbean (461) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 4.6%; US-born Caribbean, 16.4%; foreign-born Caribbean, 4.9% | None | N/A |

| Mereish, 201657 | NSAL; men (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–3 | Non-Caribbean (1201); Caribbean (545) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 0.51; Caribbean, 0.49 | Noned | N/A |

| Molina, 201658 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1418) | None | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.76%; Caribbean, 6.70%; Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 1.58 (NS). Effect modification: for Caribbean immigrants, but not African Americans, internalized racism was associated with decreased odds of MDD. | Noned | N/A |

| Taylor, 202062 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (11) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.70; Caribbean, 6.40 | None | N/A |

| Taylor, 202062 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–24 | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (11) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 3.81; Caribbean: 3.52 | None | N/A |

| Williams, 200759 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1621); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean: 10.4%; Caribbean: 12.9%; within Caribbean ethnicity (P < 0.05) US-born Caribbean, 19.8%; foreign-born Caribbean, 8.9% | None | N/A |

| Williams, 200759 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570) Caribbean (1621); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean, 5.9%; Caribbean, 7.2%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born Caribbean, 10.9%; foreign-born Caribbean, 2.0% | None | N/A |

| Woodward, 201261 | CPES; adults aged ≥55 years (2001–2003) | MDD or dysthymia | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean ≥55 years old (780); Caribbean ≥55 years old (262) | White, Latinx, Asian | Prevalence: non-Caribbean ≥55 years old, 5.4%; Caribbean aged ≥55 years, 11.2%. Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean aged ≥55 years (ref); Caribbean aged ≥55 years, 3.17 (P < 0.05) | Measurement error, religiosity | A posteriori |

| Woodward, 201360 | NSAL; adults aged ≥50 years (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years (1074); Caribbean aged ≥50 years (415) | White | Prevalence (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 8.8%; Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 11.2% | None | N/A |

| Woodward, 201360 | NSAL; adults aged ≥50 years (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years (1074); Caribbean aged ≥50 years (415) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 4.0%; Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 8.1% | None | N/A |

Abbreviations: AUDADIS, Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression; CPES, Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiological Studies; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; ECLS-B, Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey–Birth Cohort; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; K6, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; MDE, major depressive episode; N/A, not applicable; NESARC, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NR, not reported; NS, nonsignificant; NSAL, National Survey of American Life; OR, odds ratio; PHQ-2, Patient Health Questionnaire containing the first 2 questions of the 9-item PHQ-9; ref, referent; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; SPD, serious psychological distress; WMH-CIDI, World Mental Health version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

a Mechanism basis reasoning about whether the listed mechanism was a clear hypothesis in the given study raised in the introduction section (a priori) or if it was raised in the discussion section alone (a posteriori).

b The focus of these studies was to test hypotheses related to subgroup variation in main effects (ie, effect modification).

c Proposed mechanism(s) refers to within-Black racial differences in prevalence or mean levels.

d The healthy immigrant effect is technically not a mechanism but rather an observed pattern of better health outcomes among the foreign-born immigrants compared with the US-born group.

eDepression measure was treated as a covariate rather than as an outcome.

Findings from studies on depression and related symptoms within the US Black population disaggregating by immigration- and ethnicity-related domains among adults (n = 33 studies).

| First author, yearreference no. . | Data source (collection period) . | Depression measure . | Recall . | Instrument . | Cutoff score or description . | Black subgroups (no.) . | Non-Black subgroups . | Summary of findings . | Proposed mechanismsa . | Mechanism reasoninga . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain: Nativity and region of birth (n = 11 studies) | ||||||||||

| Dey, 200631 | NHIS (1998–2003) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥13 | US-born (NR);foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: US-born, 3.3%; foreign-born, 1.9% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Doe, 201732 | Community sample of mothers, New York City, NY (2015) | Probable postpartum depression | NR | EPDS | ≥9 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | US-born Latinx, foreign-born Latinx | Prevalence: US-born, 22.81%; foreign-born, 23.81% | None | N/A |

| Donovan, 201333 | Multisite study of college students (2008–2009) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 20 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 1–100 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 896 | Asian, Latinx, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Mean (NS): US-born, 51.81; foreign-born, 49.81 | None | N/A |

| Elo, 201038 | Community sample of pregnant women, Philadelphia, PA (1999–2004) | Probable depression | NR | CES-D | ≥23 | US-born (2816); foreign-born African (106); foreign-born Caribbean (179) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 21.7%; foreign-born, 25.6%; foreign-born African, 22.6%; foreign-born Caribbean, 27.4%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 1.52 (NS); foreign-born Caribbean, 1.61 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Henning-Smith, 201334 | Random sample of enrollees in Minnesota Health Care Programs (2008) | Probable depression | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | ≥3 | US-born (242); Somali-born (288) | White | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 31.6%; Somali-born: 9.1% | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Huang, 200735 | ELCS-B; mothers (2001–2002) | Depressive symptoms | NR | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Categorical; severe, ≥15; moderate, 10–14; mild, 5–9; no depression, 0–4 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity, when possible | Severe depression prevalence: US-born, 10.7%; foreign-born, 4.9%. Moderate depression prevalence: US-born, 15.2%; foreign-born, 16.9% Mild depression prevalence: US-born, 30.6%; foreign-born, 20.7% | None | N/A |

| Kreiger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston (2003–2004) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥ 13 | US-born (193); foreign-born (275) | None | Prevalence: US-born: 14.2%; foreign-born: 16.2% | None | N/A |

| Krieger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston, MA (2003–2004) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–24 | US-born(193); foreign-born (275) | None | Mean US-born, 6.6; foreign-born, 8.3 | None | N/A |

| Marquez-Velarde, 202139 | NHIS (2000–2018) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Categorical; severe: ≥13 moderate: 5–12; low or no distress: 0–4 | US-born (216 538); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean (14 725); foreign-born South American (1386); foreign-born European (857); foreign-born African (7537) | None | Moderate to severe distress prevalence: US-born, 14.3%; foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 14.9%; foreign-born South American, 9.1%; foreign-born European, 15.6%; foreign-born African, 13.2%. Moderate to severe distress ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 0.795 (P < 0.05); foreign-born South American, 0.499 (P < 0.05); foreign-born European, 1.034 (NS); foreign-born African: 0.810 (P < 0.05) | Racial context hypothesis | A priori |

| Miranda, 200540 | Community sample of low-income mothers; Washington, DC, Maryland, Virginia area (1997–2001) | Probable depression | Past month | PRIME-MD | NR | US-born (7965); foreign-born African (913); foreign-born Caribbean (273) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 10.5%; foreign-born African, 3.9%; foreign-born Caribbean, 4.8% Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 0.34 (P < 0.05); foreign-born Caribbean, 0.42 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Schwarz, 201237 | New York City Community Health Survey; women only (2002, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008) | Probable depression | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥7 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 7655 | White, Latinx; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence (NS): US-born, 24.2%; foreign-born: 23.6%. Adjusted OR: US-born (ref); foreign-born, 1.01 (NS) | None | N/A |

| Zick, 201941 | Community sample of women, Utah (2012–2015) | Depressive symptoms | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | Continuous; range, 0–6 | US-born (96); foreign-born African (79) | Latina, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and White | Mean US-born, 1.04; foreign-born African, 2.02 | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Domain: Age at immigration (n = 1 study) | ||||||||||

| Breslau, 200942 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD, dysthymia or bipolar disorder | Lifetime | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | US-born (7541); immigrated at <13 years of age (153); immigrated at ≥13 years of age (613) | Latinx: Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Central/South America; White: Western Europe, Eastern Europe. Each group was additionally disaggregated by age at immigration. | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 16.28%; immigrated at <13 years of age, 12.67%; immigrated ≥13 years of age, 7.72%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); immigrated at <13 years of age: 0.98 (NS); immigrated at ≥13 years of age, 0.43 (P < 0.05) | Childhood socialization in the United States | A priori |

| Domain: Caribbean ethnic origin (n = 21 studies) | ||||||||||

| Anglin, 201443 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3464); US-born Caribbean (373); foreign-born Caribbean (1114) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 5.3%; US-born Caribbean, 13.4%; foreign-born Caribbean, 5.6% | Subgroup variation in main effects | A priori |

| Assari, 201444 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1621) | None | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 5.4%; Caribbean, 7.8% | None | N/A |

| Boyd, 201145 | NSAL; mothers (2001–2003) | MDE | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (2019); Caribbean (799) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 14.51%; Caribbean, 15.22% | None | N/A |

| Boyd, 201145 | NSAL; mothers (2001–2003) | MDE | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (2019); Caribbean (799) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean: 7.95%; Caribbean: 6.77% | None | N/A |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3434); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher MDD prevalence relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDE | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3433); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher MDE prevalence relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Brewton-Tiayon, 201546 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3578); US-born Caribbean (432); foreign-born Caribbean (1141) | None | US-born Caribbean people generally had a higher mean CES-D score relative to both foreign-born Caribbean and non-Caribbean people | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Doyle, 201247 | NSAL; fathers (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (1254); US-born Caribbean (175); foreign-born Caribbean (458) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05); non-Caribbean: 6.9%; US-born Caribbean, 20.2%; foreign-born Caribbean: 8.3% | Acculturation | A posteriori |

| Erving, 202148 | NSAL; adults aged ≥40 years (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (1616); Caribbean (601) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.17; Caribbean: 5.90 | Noneb | N/A |

| Gibbs, 201363 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD | Lifetime | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (7529); Caribbean (469) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 9.10%; Caribbean, 4.27%. Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 0.57 (P < 0.05) | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Gibbs, 201363 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD | Past year | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (7529); Caribbean (469) | White | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 4.58%; Caribbean, 2.22% Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 0.58 (NS) | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| González, 201049 | CPES (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Foreign-born Caribbean (66.6%); US-born Caribbean (33.4%); Caribbean total = 1476. Foreign-born non-Caribbean (2.3%); US-born non-Caribbean (97.1%); non-Caribbean total = 4249 | Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence Foreign-born Caribbean, 9.1%; US-born Caribbean, 24.1%; foreign-born non-Caribbean, 13.4%; US-born non-Caribbean, 13.1% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| González, 201049 | CPES (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Foreign-born Caribbean (66.6%); US-born Caribbean (33.4%); Caribbean total = 1476. Foreign-born non-Caribbean (2.3%); US-born non-Caribbean (97.1%); non-Caribbean total = 4249 | Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: foreign-born Caribbean, 4.8%; US-born Caribbean, 13.4%; foreign-born non-Caribbean, 8.0%; US-born non-Caribbean, 7.2% | Healthy immigrant effect c | A posteriori |

| Griffith, 201150 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3570); US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 6.70; US-born Caribbean, 7.45; foreign-born Caribbean, 5.81 | Nonee | N/A |

| Head, 201751 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–4 | Non-Caribbean (3414); US-born Caribbean (446); foreign-born Caribbean (1114) | None | Mean (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean, 0.521; US-born Caribbean, 0.635; foreign-born Caribbean, 0.417 | Noneb | N/A |

| Ida, 201252 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (2953); Caribbean (1140) | None | Mean (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean, 6.60; Caribbean: 6.25 | Noneb | N/A |

| Jimenez, 201053 | CPES; adults aged ≥60 years (2001–2003) | MDE, dysthymia | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (671); Caribbean (163); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (34); foreign-born Caribbean (159) | White, Latinx, Asian; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 5.4%; Caribbean, 8.1%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born, 13.6%; foreign-born, 5.7% | None | N/A |

| Jimenez, 201053 | CPES; adults aged ≥60 years (2001–2003) | MDE, dysthymia | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (671); Caribbean (163); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (34); foreign-born Caribbean (159) | White, Latinx, Asian Each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity. | Prevalence: non-Caribbean, 2.3%; Caribbean, 4.6%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born, 9.2%; foreign-born, 2.6% | None | N/A |

| Jones, 202054 | NSAL; women only (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Nativity and Caribbean ethnicity: US-born non-Caribbean (2242); US-born Caribbean (264); foreign-born Caribbean (705) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 14.4%; US-born Caribbean, 22.6%; oreign-born Caribbean, 11.2% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Jones, 202054 | NSAL; women only (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Nativity and Caribbean ethnicity: US-born non-Caribbean (2242); US-born Caribbean (264); foreign-born Caribbean (705) | None | Prevalence: US-born non-Caribbean, 8.2%; US-born Caribbean, 7.5%; foreign-born Caribbean, 7.0% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Lincoln, 200755 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3361); Caribbean (1554) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 6.78; Caribbean: 6.07 | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Mays, 201856 | NSAL; men only (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | US-born non-Caribbean (1222); US-born Caribbean (176); foreign-born Caribbean (461) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 8.8%; US-born Caribbean, 21.1%; foreign-born Caribbean, 8.9% | None | N/A |

| Mays, 201856 | NSAL; men only (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | US-born non-Caribbean (1222); US-born Caribbean (176); foreign-born Caribbean (461) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born non-Caribbean, 4.6%; US-born Caribbean, 16.4%; foreign-born Caribbean, 4.9% | None | N/A |

| Mereish, 201657 | NSAL; men (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–3 | Non-Caribbean (1201); Caribbean (545) | None | Mean: non-Caribbean, 0.51; Caribbean, 0.49 | Noned | N/A |

| Molina, 201658 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1418) | None | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.76%; Caribbean, 6.70%; Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean (ref); Caribbean, 1.58 (NS). Effect modification: for Caribbean immigrants, but not African Americans, internalized racism was associated with decreased odds of MDD. | Noned | N/A |

| Taylor, 202062 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 0–36 | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (11) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 6.70; Caribbean, 6.40 | None | N/A |

| Taylor, 202062 | NSAL (2001–2003) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–24 | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (11) | None | Mean (NS): non-Caribbean, 3.81; Caribbean: 3.52 | None | N/A |

| Williams, 200759 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570); Caribbean (1621); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean: 10.4%; Caribbean: 12.9%; within Caribbean ethnicity (P < 0.05) US-born Caribbean, 19.8%; foreign-born Caribbean, 8.9% | None | N/A |

| Williams, 200759 | NSAL (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean (3570) Caribbean (1621); within Caribbean ethnicity US-born Caribbean (440); foreign-born Caribbean (1166) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean, 5.9%; Caribbean, 7.2%; within Caribbean ethnicity (NS) US-born Caribbean, 10.9%; foreign-born Caribbean, 2.0% | None | N/A |

| Woodward, 201261 | CPES; adults aged ≥55 years (2001–2003) | MDD or dysthymia | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean ≥55 years old (780); Caribbean ≥55 years old (262) | White, Latinx, Asian | Prevalence: non-Caribbean ≥55 years old, 5.4%; Caribbean aged ≥55 years, 11.2%. Adjusted OR: non-Caribbean aged ≥55 years (ref); Caribbean aged ≥55 years, 3.17 (P < 0.05) | Measurement error, religiosity | A posteriori |

| Woodward, 201360 | NSAL; adults aged ≥50 years (2001–2003) | MDD | Lifetime | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years (1074); Caribbean aged ≥50 years (415) | White | Prevalence (P < 0.05): non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 8.8%; Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 11.2% | None | N/A |

| Woodward, 201360 | NSAL; adults aged ≥50 years (2001–2003) | MDD | Past year | WMH-CIDI | DSM-IV criteria | Non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years (1074); Caribbean aged ≥50 years (415) | White | Prevalence (NS): non-Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 4.0%; Caribbean aged ≥50 years, 8.1% | None | N/A |

| First author, yearreference no. . | Data source (collection period) . | Depression measure . | Recall . | Instrument . | Cutoff score or description . | Black subgroups (no.) . | Non-Black subgroups . | Summary of findings . | Proposed mechanismsa . | Mechanism reasoninga . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain: Nativity and region of birth (n = 11 studies) | ||||||||||

| Dey, 200631 | NHIS (1998–2003) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥13 | US-born (NR);foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence: US-born, 3.3%; foreign-born, 1.9% | Healthy immigrant effectc | A posteriori |

| Doe, 201732 | Community sample of mothers, New York City, NY (2015) | Probable postpartum depression | NR | EPDS | ≥9 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | US-born Latinx, foreign-born Latinx | Prevalence: US-born, 22.81%; foreign-born, 23.81% | None | N/A |

| Donovan, 201333 | Multisite study of college students (2008–2009) | Depressive symptoms | Past 7 days | 20 items adapted from CES-D | Continuous; range: 1–100 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 896 | Asian, Latinx, and White; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Mean (NS): US-born, 51.81; foreign-born, 49.81 | None | N/A |

| Elo, 201038 | Community sample of pregnant women, Philadelphia, PA (1999–2004) | Probable depression | NR | CES-D | ≥23 | US-born (2816); foreign-born African (106); foreign-born Caribbean (179) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 21.7%; foreign-born, 25.6%; foreign-born African, 22.6%; foreign-born Caribbean, 27.4%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 1.52 (NS); foreign-born Caribbean, 1.61 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Henning-Smith, 201334 | Random sample of enrollees in Minnesota Health Care Programs (2008) | Probable depression | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | ≥3 | US-born (242); Somali-born (288) | White | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 31.6%; Somali-born: 9.1% | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Huang, 200735 | ELCS-B; mothers (2001–2002) | Depressive symptoms | NR | 12 items adapted from CES-D | Categorical; severe, ≥15; moderate, 10–14; mild, 5–9; no depression, 0–4 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR) | White, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity, when possible | Severe depression prevalence: US-born, 10.7%; foreign-born, 4.9%. Moderate depression prevalence: US-born, 15.2%; foreign-born, 16.9% Mild depression prevalence: US-born, 30.6%; foreign-born, 20.7% | None | N/A |

| Kreiger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston (2003–2004) | SPD | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥ 13 | US-born (193); foreign-born (275) | None | Prevalence: US-born: 14.2%; foreign-born: 16.2% | None | N/A |

| Krieger, 201136 | Community sample, Boston, MA (2003–2004) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Continuous; range: 0–24 | US-born(193); foreign-born (275) | None | Mean US-born, 6.6; foreign-born, 8.3 | None | N/A |

| Marquez-Velarde, 202139 | NHIS (2000–2018) | Psychological distress | Past 30 days | K6 | Categorical; severe: ≥13 moderate: 5–12; low or no distress: 0–4 | US-born (216 538); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean (14 725); foreign-born South American (1386); foreign-born European (857); foreign-born African (7537) | None | Moderate to severe distress prevalence: US-born, 14.3%; foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 14.9%; foreign-born South American, 9.1%; foreign-born European, 15.6%; foreign-born African, 13.2%. Moderate to severe distress ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born Mexican/Central American/Caribbean, 0.795 (P < 0.05); foreign-born South American, 0.499 (P < 0.05); foreign-born European, 1.034 (NS); foreign-born African: 0.810 (P < 0.05) | Racial context hypothesis | A priori |

| Miranda, 200540 | Community sample of low-income mothers; Washington, DC, Maryland, Virginia area (1997–2001) | Probable depression | Past month | PRIME-MD | NR | US-born (7965); foreign-born African (913); foreign-born Caribbean (273) | None | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 10.5%; foreign-born African, 3.9%; foreign-born Caribbean, 4.8% Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); foreign-born African, 0.34 (P < 0.05); foreign-born Caribbean, 0.42 (P < 0.05) | None | N/A |

| Schwarz, 201237 | New York City Community Health Survey; women only (2002, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008) | Probable depression | Past 30 days | K6 | ≥7 | US-born (NR); foreign-born (NR); N = 7655 | White, Latinx; each group was additionally disaggregated by nativity | Prevalence (NS): US-born, 24.2%; foreign-born: 23.6%. Adjusted OR: US-born (ref); foreign-born, 1.01 (NS) | None | N/A |

| Zick, 201941 | Community sample of women, Utah (2012–2015) | Depressive symptoms | Past 2 weeks | PHQ-2 | Continuous; range, 0–6 | US-born (96); foreign-born African (79) | Latina, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and White | Mean US-born, 1.04; foreign-born African, 2.02 | Measurement error | A posteriori |

| Domain: Age at immigration (n = 1 study) | ||||||||||

| Breslau, 200942 | NESARC (2001–2002) | MDD, dysthymia or bipolar disorder | Lifetime | AUDADIS DSM-IV version | DSM-IV criteria | US-born (7541); immigrated at <13 years of age (153); immigrated at ≥13 years of age (613) | Latinx: Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Central/South America; White: Western Europe, Eastern Europe. Each group was additionally disaggregated by age at immigration. | Prevalence (P < 0.05): US-born, 16.28%; immigrated at <13 years of age, 12.67%; immigrated ≥13 years of age, 7.72%. Adjusted ORs: US-born (ref); immigrated at <13 years of age: 0.98 (NS); immigrated at ≥13 years of age, 0.43 (P < 0.05) | Childhood socialization in the United States | A priori |

| Domain: Caribbean ethnic origin (n = 21 studies) | ||||||||||